Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (/dɑːrdəˈnɛlz/; Turkish: Çanakkale Boğazı, lit. 'Strait of Çanakkale', Greek: Δαρδανέλλια, romanized: Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (/ˈhɛlɪspɒnt/; Classical Greek: Ἑλλήσποντος, romanized: Hellēspontos, lit. 'Sea of Helle'), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey that forms part of the continental boundary between Asia and Europe and separates Asian Turkey from European Turkey. Together with the Bosporus, the Dardanelles forms the Turkish Straits.

| Dardanelles (Çanakkale Boğazı) | |

|---|---|

| Strait of Gallipoli | |

Close-up topographic map of the Dardanelles | |

Dardanelles (Çanakkale Boğazı)  Dardanelles (Çanakkale Boğazı) | |

| Coordinates | 40.2°N 26.4°E |

| Type | Strait |

| Part of | Turkish Straits |

| Basin countries | Turkey |

| Max. length | 61 km (38 mi) |

| Min. width | 1.2 km (0.75 mi) |

One of the world's narrowest straits used for international navigation, the Dardanelles connects the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean and Mediterranean seas while also allowing passage to the Black Sea by extension via the Bosporus. The Dardanelles is 61 kilometres (38 mi) long and 1.2 to 6 kilometres (0.75 to 3.73 mi) wide. It has an average depth of 55 metres (180 ft) with a maximum depth of 103 metres (338 ft) at its narrowest point abreast the city of Çanakkale. The first fixed crossing across the Dardanelles opened in 2022 with the completion of the 1915 Çanakkale Bridge.

Most of the northern shores of the strait along the Gallipoli peninsula (Turkish: Gelibolu) are sparsely settled, while the southern shores along the Troad peninsula (Turkish: Biga) are inhabited by the city of Çanakkale's urban population of 110,000.

Names

The contemporary Turkish name Çanakkale Boğazı, meaning 'Çanakkale Strait', is derived from the eponymous midsize city that adjoins the strait, itself meaning 'pottery fort'—from چاناق (çanak, 'pottery') + قلعه (kale, 'fortress')—in reference to the area's famous pottery and ceramic wares, and the landmark Ottoman fortress of Sultaniye.

The English name Dardanelles is an abbreviation of Strait of the Dardanelles. During Ottoman times there was a castle on each side of the strait. These castles together were called the Dardanelles,[1][2] probably named after Dardanus, an ancient city on the Asian shore of the strait which in turn was said to take its name from Dardanus, the mythical son of Zeus and Electra.

The ancient Greek name Ἑλλήσποντος (Hellēspontos) means "Sea of Helle", and was the ancient name of the narrow strait. It was variously named in classical literature Hellespontium Pelagus, Rectum Hellesponticum, and Fretum Hellesponticum. It was so called from Helle, the daughter of Athamas, who was drowned here in the mythology of the Golden Fleece.

Geography

As a maritime waterway, the Dardanelles connects various seas along the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Near East, and Western Eurasia, and specifically connects the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. The Marmara further connects to the Black Sea via the Bosporus, while the Aegean further links to the Mediterranean. Thus, the Dardanelles allows maritime connections from the Black Sea all the way to the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean via Gibraltar, and the Indian Ocean through the Suez Canal, making it a crucial international waterway, in particular for the passage of goods coming in from Russia.

The strait is located at approximately 40°13′N 26°26′E.

Present morphology

The strait is 61 kilometres (38 mi) long, and 1.2 to 6 kilometres (0.7 to 3.7 mi) wide, averaging 55 metres (180 ft) deep with a maximum depth of 103 metres (338 ft) at its narrowest point at Nara Burnu, abreast Çanakkale. There are two major currents through the strait: a surface current flows from the Black Sea towards the Aegean Sea, and a more saline undercurrent flows in the opposite direction.[3]

The Dardanelles is unique in many respects. The very narrow and winding shape of the strait is more akin to that of a river. It is considered one of the most hazardous, crowded, difficult and potentially dangerous waterways in the world. The currents produced by the tidal action in the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara are such that ships under sail must wait at anchorage for the right conditions before entering the Dardanelles.

History

As part of the only passage between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, the Dardanelles has always been of great importance from a commercial and military point of view, and remains strategically important today. It is a major sea access route for numerous countries, including Russia and Ukraine. Control over it has been an objective of a number of hostilities in modern history, notably the attack of the Allied Powers on the Dardanelles during the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli in the course of World War I.

Greek and Persian history

The ancient city of Troy was located near the western entrance of the strait, and the strait's Asiatic shore was the focus of the Trojan War. Troy was able to control the marine traffic entering this vital waterway. The Persian army of Xerxes I of Persia and later the Macedonian army of Alexander the Great crossed the Dardanelles in opposite directions to invade each other's lands, in 480 BC and 334 BC respectively.

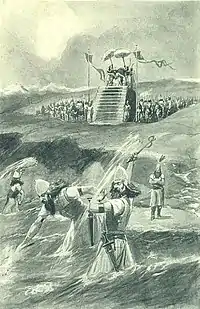

Herodotus says that, circa 482 BC, Xerxes I (the son of Darius) had two pontoon bridges built across the width of the Hellespont at Abydos, in order that his huge army could cross from Persia into Greece. This crossing was named by Aeschylus in his tragedy The Persians as the cause of divine intervention against Xerxes.[4]

According to Herodotus (vv.34), both bridges were destroyed by a storm and Xerxes had those responsible for building the bridges beheaded and the strait itself whipped. The Histories of Herodotus vii.33–37 and vii.54–58 give details of building and crossing of Xerxes' Pontoon Bridges. Xerxes is then said to have thrown fetters into the strait, given it three hundred lashes and branded it with red-hot irons as the soldiers shouted at the water.[5]

Herodotus commented that this was a "highly presumptuous way to address the Hellespont" but in no way atypical of Xerxes. (vii.35)

Harpalus the engineer is said to have eventually helped the invading armies to cross by lashing the ships together with their bows facing the current and adding two additional anchors to each ship.

From the perspective of ancient Greek mythology Helle, the daughter of Athamas, supposedly was drowned at the Dardanelles in the legend of the Golden Fleece. Likewise, the strait was the scene of the legend of Hero and Leander, wherein the lovesick Leander swam the strait nightly in order to tryst with his beloved, the priestess Hero, but was ultimately drowned in a storm.

Byzantine history

The Dardanelles were vital to the defence of Constantinople during the Byzantine period.

Also, the Dardanelles was an important source of income for the ruler of the region. At the Istanbul Archaeological Museum a marble plate contains a law by the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I (491–518 AD), that regulated fees for passage through the customs office of the Dardanelles. Translation:

... Whoever dares to violate these regulations shall no longer be regarded as a friend, and he shall be punished. Besides, the administrator of the Dardanelles must have the right to receive 50 golden Litrons, so that these rules, which we make out of piety, shall never ever be violated... ... The distinguished governor and major of the capital, who already has both hands full of things to do, has turned to our lofty piety in order to reorganize the entry and exit of all ships through the Dardanelles... ... Starting from our day and also in the future, anybody who wants to pass through the Dardanelles must pay the following:

– All wine merchants who bring wine to the capital (Constantinopolis), except Cilicians, have to pay the Dardanelles officials 6 follis and 2 sextarius of wine.

– In the same manner, all merchants of olive-oil, vegetables and lard must pay the Dardanelles officials 6 follis. Cilician sea-merchants have to pay 3 follis and in addition to that, 1 keration (12 follis) to enter, and 2 keration to exit.– All wheat merchants have to pay the officials 3 follis per modius, and a further sum of 3 follis when leaving.

Since the 14th century the Dardanelles have almost continuously been controlled by the Turks.

Ottoman era (1354–1922)

The Dardanelles continued to constitute an important waterway during the period of the Ottoman Empire, which conquered Gallipoli in 1354.

Ottoman control of the strait continued largely without interruption or challenges until the 19th century, when the Empire started its decline.

Nineteenth century

Gaining control of, or guaranteed access to, the strait became a key foreign-policy goal of the Russian Empire during the 19th century. During the Napoleonic Wars, Russia—supported by Great Britain in the Dardanelles Operation—blockaded the straits in 1807.

In 1833, following the Ottoman Empire's defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, Russia pressured the Ottomans to sign the Treaty of Hunkiar Iskelesi—which required the closing of the straits to warships of non-Black Sea powers at Russia's request. That would have effectively given Russia a free hand in the Black Sea.

This treaty alarmed the Ottoman Empire, who were concerned that the consequences of potential Russian expansionism in the Black Sea and Mediterranean regions could conflict with their own possessions and economic interest in the region. At the London Straits Convention in July 1841, the United Kingdom, France, Austria, and Prussia pressured Russia to agree that only Turkish warships could traverse the Dardanelles in peacetime. The United Kingdom and France subsequently sent their fleets through the straits to defend the Danube front and to attack the Crimean Peninsula during the Crimean War of 1853–1856 – but they did so as allies of the Ottoman Empire. Following the defeat of Russia in the Crimean War, the Congress of Paris in 1856 formally reaffirmed the London Straits Convention. It remained technically in force into the 20th and 21st centuries.

World War I

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 1915 the Allies sent a substantial invasion force of British, Indian, Australian, New Zealand, French and Newfoundland troops to attempt to open up the straits. In the Gallipoli campaign, Turkish troops trapped the Allies on the coasts of the Gallipoli peninsula. The campaign damaged the career of Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty (in office 1911–1915), who had eagerly promoted the (unsuccessful) use of Royal Navy sea-power to force open the straits. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, subsequent founder of the Republic of Turkey, served as an Ottoman commander during the land campaign.

The Turks mined the straits to prevent Allied ships from penetrating them but, in minor actions two submarines, one British and one Australian, did succeed in penetrating the minefields. The British submarine sank an obsolete Turkish pre-dreadnought battleship off the Golden Horn of Istanbul. Sir Ian Hamilton's Mediterranean Expeditionary Force failed in its attempt to capture the Gallipoli peninsula, and the British cabinet ordered its withdrawal in December 1915, after eight months' fighting. Total Allied deaths included 43,000 British, 15,000 French, 8,700 Australians, 2,700 New Zealanders, 1,370 Indians and 49 Newfoundlanders.[6] Total Turkish deaths were around 60,000.

Following the war, the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres demilitarized the strait and made it an international territory under the control of the League of Nations. The Ottoman Empire's non-ethnically Turkish territories were broken up and partitioned among the Allied Powers, and Turkish jurisdiction over the straits curbed.

Turkish republican and modern eras (1923–present)

After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire following a lengthy campaign by Turks as part of the Turkish War of Independence against both the Allied Powers and the Ottoman court, the Republic of Turkey was created in 1923 by the Treaty of Lausanne, which established most of the modern sovereign territory of Turkey and restored the straits to Turkish territory, with the condition that Turkey keep them demilitarized and allow all foreign warships and commercial shipping to traverse the straits freely.

As part of its national security strategy, Turkey eventually rejected the terms of the treaty, and subsequently remilitarized the straits area over the following decade. Following extensive diplomatic negotiations, the reversion was formalized under the Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Turkish Straits on 20 July 1936. That convention, which is still in force today, treats the straits as an international shipping lane while allowing Turkey to retain the right to restrict the naval traffic of non-Black Sea states.

During World War II, through February 1945, when Turkey was neutral for most of the length of the conflict, the Dardanelles were closed to the ships of the belligerent nations. Turkey declared war on Germany in February 1945, but it did not employ any offensive forces during the war.

In July 1946, the Soviet Union sent a note to Turkey proposing a new régime for the Dardanelles that would have excluded all nations except the Black Sea powers. The second proposal was that the straits should be put under joint Turkish-Soviet defence. This meant that Turkey, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria and Romania would be the only states having access to the Black Sea through the Dardanelles. The Turkish government however, under pressure from the United States, rejected these proposals.[7]

Turkey joined NATO in 1952, thus affording its straits even more strategic importance as a commercial and military waterway.

In more recent years, the Turkish Straits have become particularly important for the oil industry. Russian oil, from ports such as Novorossyisk, is exported by tankers primarily to western Europe and the U.S. via the Bosporus and the Dardanelles straits.

Crossings

Maritime

The waters of the Dardanelles are traversed by numerous passenger and vehicular ferries daily, as well as recreational and fishing boats ranging from dinghies to yachts owned by both public and private entities.

The strait also experiences significant amounts of commercial shipping traffic.

Land

The Çanakkale 1915 Bridge joins Lapseki, a district of Çanakkale, on the Asian side and Sütlüce, a village of the Gelibolu district, on the European side.[9] It is part of planned expansions to the Turkish National Highway Network. Work on the bridge began in March 2017, and it was opened on March 18, 2022.[10]

Subsea

2 submarine cable systems transmitting electric power at 400 kV bridge the Dardanelles to feed west and east of Istanbul. They have their own landing stations in Lapseki and Sütlüce. The first, situated in the northeast quarter portion of the strait, was energised in April 2015 and provides 2 GW via 6 phases 400 kV AC 3.9 km far through the sea. The second, somewhat in the middle of the strait, was still under construction in June 2016 and will provide similar capabilities to the first line.

Both subsea power lines cross 4 optical fibre data lines laid earlier along the strait.[11] A published map shows communication lines leading from Istanbul into the Mediterranean, named MedNautilus and landing at Athens, Sicily and elsewhere.[12]

Image gallery

Marble plate with 6th century AD Byzantine law regulating payment of customs in the Dardanelles

Marble plate with 6th century AD Byzantine law regulating payment of customs in the Dardanelles Historic map of the Dardanelles by Piri Reis

Historic map of the Dardanelles by Piri Reis

Map of the Dardanelles drawn by G. F. Morrell, 1915, showing the Gallipoli peninsula and the west coast of Turkey, as well as the location of front line troops and landings during the Gallipoli Campaign

Map of the Dardanelles drawn by G. F. Morrell, 1915, showing the Gallipoli peninsula and the west coast of Turkey, as well as the location of front line troops and landings during the Gallipoli Campaign A view of the Dardanelles from Gallipoli peninsula

A view of the Dardanelles from Gallipoli peninsula A view of Çanakkale from the Dardanelles

A view of Çanakkale from the Dardanelles Ferry line across the Dardanelles in Çanakkale

Ferry line across the Dardanelles in Çanakkale Aerial view of the city of Çanakkale

Aerial view of the city of Çanakkale Dardanelles in 2021

Dardanelles in 2021

See also

- Action of 26 June 1656

- Battle of the Dardanelles (disambiguation)

- Dardanelles Commission

- List of maritime incidents in the Turkish Straits

References

- Hoogstraten, David van; Nidek, Matthaeus Brouërius van; Schuer, Jan Lodewyk (1727). "Dardanellen". Groot algemeen historisch, geografisch, genealogisch, en oordeelkundig woordenboek (in Dutch). Vol. 4: D en E. Amsterdam/Utrecht/The Hague. p. 25. OCLC 1193061215. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017.

- Crabb, George (1833). "Dardanelles". Universal Historical Dictionary. Vol. 1. London. OCLC 1158045075.

- Rozakis, Christos L.; Stagos, Petros N. (1987). The Turkish Straits. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 90-247-3464-9. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Aeschylus. "The Persians". Translated by Potter, Robert. Archived from the original on 19 November 2003. Retrieved 26 September 2003 – via The Internet Classics Archive.

- Green, Peter (1996). The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley; London: The University of California Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-520-20573-1.

- "Gallipoli casualties by country". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Cabell, Phillips B. H. (1966). The Truman presidency : the history of a triumphant succession. New York: Macmillan. pp. 102–103. OCLC 1088163662.

- "Groundbreaking ceremony for bridge over Dardanelles to take place on March 18". Hürriyet Daily News. 17 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "Project Information". 1915 Çanakkale Bridge. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- "Turkey opens record-breaking bridge between Europe and Asia". CNN. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Yüce, Gülnazi (7–8 June 2016). Submarine Cable Projects (2-03) (PDF). First South East European Regional CIGRÉ Conference. Portorož, Slovenia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Submarine Cable Map 2017". TeleGeography. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

External links

- Pictures of the city of Çanakkale

- Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University

- Map of Hellespont

- Livius.org: Hellespont Archived 1 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Monuments and memorials of the Gallipoli campaign along the Dardanelles

- Old Maps of the Dardanelles, Eran Laor Cartographic collection, The National Library of Israel