David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros (born José de Jesús Alfaro Siqueiros; December 29, 1896 – January 6, 1974) was a Mexican social realist painter, best known for his large public murals using the latest in equipment, materials and technique. Along with Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, he was one of the most famous of the "Mexican muralists".[1] He was a member of the Mexican Communist Party, and a Stalinist and supporter of the Soviet Union who led an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Leon Trotsky in May 1940.[2]

David Alfaro Siqueiros | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Siqueiros, year unknown | |

| Born | December 29, 1896 Chihuahua, Mexico |

| Died | January 6, 1974 (aged 77) Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Education | San Carlos Academy |

| Known for | Painting, Muralist |

| Notable work | Portrait of the Bourgeoisie (1939–1940), The March of Humanity (1957–1971) |

| Movement | Mexican Mural Movement, Social Realism |

| Awards | Lenin Peace Prize 1966 |

By accordance with Spanish naming customs, his surname would normally have been Alfaro; however, like Picasso (Pablo Ruiz y Picasso) and Lorca (Federico García Lorca), Siqueiros used his mother's surname. It was long believed that he was born in Camargo in Chihuahua state, but in 2003 it was proven that he had actually been born in the city of Chihuahua, but grew up in Irapuato, Guanajuato, at least from the age of six. The discovery of his birth certificate in 2003 by a Mexican art curator was announced the following year by art critic Raquel Tibol, who was renowned as the leading authority on Mexican Muralism[3] and who had been a close acquaintance of Siqueiros.[4] Siqueiros changed his given name to "David" after his first wife called him by it in allusion to Michelangelo's David.[4][5]

Early life

Many details of Siqueiros's childhood, including birth date, birthplace, first name, and where he grew up, were misstated during his life and long after his death, in some cases by himself. Often he is reported to have been born and raised in 1898 in a town in the state of Chihuahua, and his personal names are reported to be "José David". Thanks to art historian Raquel Tibol, who found a birth certificate for him, we know now that he was born in Mexico City, not Camargo or the state of Chihuahua.

Siqueiros was born in Chihuahua in 1896, the second of three children. He was baptized José de Jesús Alfaro Siqueiros.[4][5] His father, Cipriano Alfaro, originally from Irapuato, was well-off. His mother was Teresa Siqueiros. Siqueiros had two siblings: a sister, Luz, three years elder, and a brother "Chucho" (Jesús), a year younger. David's mother died when he was four and their father sent the children to live with their paternal grandparents.[6] David's grandfather, nicknamed "Siete Filos" ('seven knife-edges'), had an especially strong role in his upbringing. In 1902, Siqueiros started school in Irapuato, Guanajuato.

He credits his first rebellious influence to his sister, who had resisted their father's religious orthodoxy. Around this time, Siqueiros was also exposed to new political ideas, mainly along the lines of anarcho-syndicalism. One such political theorist was Dr. Atl, who published a manifesto in 1906 calling for Mexican artists to develop a national art and look to ancient indigenous cultures for inspiration.[7] In 1911, at the age of fifteen, Siqueiros was involved in a student strike at the Academy of San Carlos of the National Academy of Fine Arts that protested the school's teaching methodology and urged the impeachment of the school's director. Their protests eventually led to the establishment of an "open-air academy" in Santa Anita.[7]

At the age of eighteen, Siqueiros and several of his colleagues from the School of Fine Arts joined Venustiano Carranza's Constitutional Army fighting the government of President Victoriano Huerta. When Huerta fell in 1914, Siqueiros became enmeshed in the "post-revolutionary" infighting, as the Constitutional Army battled the diverse political factions of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata for control.[7] His military travels around the country exposed him to Mexican culture and the raw, everyday struggles of the working and rural poor classes. After Carranza's forces had gained control, Siqueiros briefly returned to Mexico City to paint before traveling to Europe in 1919. First in Paris, he absorbed the influence of cubism, intrigued particularly with Paul Cézanne and the use of large blocks of intense color. While there, he also met Diego Rivera, another Mexican painter of "the Big Three" on the brink of a legendary career in muralism, and he traveled to Italy to study the great fresco painters of the Renaissance.[7] In Barcelona he published a magazine, La vida Americana, in which he issued a manifesto to the artists of America to reject the decadent influence of Europe and create a new form of public art with the latest tools and technology.

Early art and politics

Although many have said that Siqueiros' artistic ventures were frequently "interrupted" by political ones, Siqueiros himself believed the two were intricately intertwined.[8] By 1921, when he wrote his manifesto in Vida Americana, Siqueiros had already been exposed to Marxism and seen the life of the working and rural poor while traveling with the Constitutional Army. In "A New Direction for the New Generation of American Painters and Sculptors", he called for a "spiritual renewal" to simultaneously bring back the virtues of classical painting while infusing this style with "new values" that acknowledged the "modern machine" and the "contemporary aspects of daily life".[9] The manifesto also claimed that a "constructive spirit" is essential to meaningful art, which rises above mere decoration or false, fantastical themes. Through this style, Siqueiros hoped to create a style that would bridge national and universal art. In his work, as well as his writing, Siqueiros sought a social realism that hailed the proletariat peoples of Mexico and the world, even as it attempted to avoid the widespread clichés of "Primitivism" and "Indianism".[10]

In 1922, Siqueiros returned to Mexico City to work as a muralist for Álvaro Obregón's revolutionary government. The then Secretary of Public Education, José Vasconcelos, made a mission of educating the masses through public art, and hired scores of artists and writers to build a modern Mexican culture. Siqueiros, Rivera and Orozco worked together under Vasconcelos, who supported the muralist movement by commissioning murals for prominent buildings in Mexico City. Still, the artists working at the Preparatoria realized that many of their early works lacked the "public" nature envisioned in their ideology. In 1923 Siqueiros helped found the Syndicate of Revolutionary Mexican Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, which addressed the problem of public access to art through its paper, El Machete. That year Siqueiros helped author a manifesto in the newspaper "for the proletariat of the world". It addressed the necessity of "collective" art, which would serve as "ideological propaganda" to educate the masses and overcome bourgeois, individualist art.

Soon after, Siqueiros painted his famous mural Burial of a Worker (1923) in the stairwell of the Colegio Chico. The fresco features a group of pre-Conquest style workers in a funeral procession that are carrying a giant coffin, decorated with a hammer and sickle.[11] The mural was never finished and was vandalized by students at the school who did not agree with the work's overtly political subject matter. Eventually, the entire mural was whitewashed by the new Minister of Education who succeeded Vasconcelos.[12] The Syndicate became ever more critical of the revolutionary government, due to the State's failure to deliver on promised reforms. As a result, its members faced new threats to cut funding for their art and the newspaper. A feud within the Syndicate—regarding a choice between publishing El Machete or losing financial support for mural projects—led to Siqueiros moving to the forefront of the organization, when Rivera left in protest over the decision to prioritize politics over art. Despite being dismissed from a post at the Department of Education in 1925, Siqueiros remained deeply involved in labor activities, in the Syndicate as well as the Mexican Communist Party, until he was jailed and eventually exiled in the early 1930s.[7]

After spending many years in Mexico and being heavily involved in radical political activities, Siqueiros went to Los Angeles, California in 1932 to continue his career as a muralist. Working in a collective unit that experimented with new painting techniques using modern devices such as airbrushes, sprayguns and projectors,[13] Siqueiros and his team of collaborators painted two major murals. The first, entitled Street Meeting, was commissioned for the Chouinard School of Art. It depicts a group of workers of mixed ethnicities listening to an angry labor agitator's speech during a break in the workday.[14] The mural was washed over within a year of its unveiling – due to weather-related issues, and perhaps the Communist content of the work. Siqueiros' other significant Los Angeles mural, Tropical America (full name: América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos, or Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism),[15] was commissioned shortly after the unveiling of Street Meeting, and was to be painted on the exterior wall of the Plaza Art Center that faced the busy Olvera Street. Tropical America depicts American imperialism in Latin America, a much more radical theme than was intended for the work. Although it received generally favorable criticism, some viewed it as Communist propaganda, which led to a partial covering in 1934 and a total whitewash in 1938.[16] Eighty years later, the Getty Conservation Institute performed restoration work on the mural.[17] As no color photographs of Tropical America are known to exist, conservators used scientific analysis and best practices to get at the artist's vision of the mural. It became accessible to the public on its 80th anniversary, October 9, 2012.[18] The América Tropical Interpretive Center that opened nearby is dedicated to the life and legacy of David Alfaro Siqueiros.[19][20]

Artistic career

In the early 1930s, including his time spent in Lecumberri Prison, Siqueiros produced a series of politically themed lithographs, many of which were exhibited in the United States. His lithograph Head was shown at the 1930 exhibition "Mexican Artists and Artists of the Mexican School" at The Delphic Studios in New York City.[21] In 1932, he led an exhibition and conference entitled "Rectifications on Mexican Muralism" at the gallery of the Spanish Casino in Taxco, Guerrero.[7] Shortly after, he traveled to New York, where he participated in the Weyhe Gallery's "Mexican Graphic Art" exhibition. Also in 1932, Nelbert Chouinard invited Siqueiros to Los Angeles to conduct mural workshops.[22] It was at this time that, with a team of students, he also completed Tropical America in 1932, at the Italian Hall at Olvera Street in Los Angeles.[23] Painting fresco on an outside wall – visible to passersby as well as intentional viewers – forced Siqueiros to reconsider his methodology as a muralist. He wanted the image – an Indian peon being crucified by American oppression – to be accessible from multiple angles. Instead of just constructing "an enlarged easel painting", he realized that the mural "must conform to the normal transit of a spectator."[10] Eventually, Siqueiros would develop a mural technique that involved tracing figures onto a wall with an electric projector, photographing early wall sketches to improve perspective, and new paints, spray guns, and other tools to accommodate the surface of modern buildings and the outdoor conditions. He was unceremoniously deported from the United States for political activity the same year.[24]

Back in New York in 1936, he was the guest of honor at the "Contemporary Arts" exhibition at the St. Regis gallery. There he also ran a political art workshop in preparation for the 1936 General Strike for Peace and May Day parade. The young Jackson Pollock attended the workshop and helped build floats for the parade. In fact, Siquieros has been credited with teaching drip and pour techniques to Pollock that later resulted in his all-over paintings, made from 1947 to 1950, and which constitute Pollock's greatest achievement. In addition to floats, the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop produced a variety of posters and other ephemeral works for the CPUSA and other anti-fascist organizations in New York. These ephemeral works possessed the ability to reach the masses in a way different from mural painting because they were accessible to a wide audience outside of an institution or gallery. The Siqueiros Experimental Workshop only lasted for a little over a year until Siqueiros went to fight in the Spanish Civil War in April 1937, but their floats were featured in both the 1936 and 1937 May Day Parades in Manhattan's garment district.[25]

Continuing to produce several works throughout the late 1930s – such as Echo of a Scream (1937) and The Sob (1939), both now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York . Although he went to Spain to support the Spanish Republic against the fascist forces of Franciso Franco with his art, he volunteered and served in frontline combat as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Army of the Republic through 1938 before returning to Mexico City. After his return, in a stairwell of the Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas, Siqueiros collaborated with Spanish refugee Josep Renau and the International Team of Plastic Artists to develop one of his most famous works, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie, warning against the dual foes of capitalism and fascism.[26] The original mural, painted in the stairwell of the electrical worker's union, incorporated cameras, photomontage, spray guns, airbrushes, stencils and the latest paints. It shows a giant generator using the opposition of fascist and capitalist democracies to generate imperialism and war. An armed, brave-faced revolutionary, of unnamable class or ethnicity, confronts the machine, and a blue sky on the ceiling flanked by electrical towers displays hope for the proletariat in technological and industrial advances.

American-born poet and eventual fellow Spanish Civil War participant Edwin Rolfe was a great admirer of Siqueiros's "ability to function" as "artist and revolutionary".[27] His 1934 poem "Room with Revolutionists" is based on a conversation between ″New Masses″ editor, poet, and Left journalist Joseph Freeman (1897–1965) and Siqueiros;[27] in it, Siqueiros is described as "a revolutionist / a painter of great areas, editor / of fiery and terrifying words, leader / of the poor who plant, the poor who burrow / under the earth in field and mine. / His life's an always upward-delving battle in / an old torn sweater, the pockets always empty."[28]

Attempted assassination of Leon Trotsky

Before the mural's completion in 1940, however, Siqueiros was forced into hiding and later exiled for his direct involvement in an attempt to assassinate Leon Trotsky, then in exile in Mexico City from the Soviet Union:[7]

President Lázaro Cárdenas had given Leon Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, political asylum after fleeing Stalinist persecution. They were able to enter the country thanks to the request that Ana Brenner made to Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo to intervene on their behalf. Trotsky's arrival in Mexico as a political asylee infuriated the Spanish Republicans, allies of the Soviet Union, who complained to the Mexican fighters -among them Siqueiros- about their government's decision to accept Trotsky.[29]

In the early morning of May 24, 1940, Siqueiros led an attack on Trotsky's house in Mexico City's Coyoacán suburb. (Trotsky, granted asylum by President Cárdenas, was then living in Mexico.) The attacking party was composed of men who had served under Siqueiros in the Spanish Civil War and of miners from his union. After thoroughly raking the house with machine gun fire and explosives, the attackers withdrew in the belief that nobody could have survived the assault. They were mistaken. Trotsky was unhurt and lived till August, when he was killed with an ice pick wielded by an assassin[30]

Trotsky's 13-year-old grandson was shot, yet survived.[31] Following the attack, police found a shallow grave[32] on the road to the Desierto de los Leones with the body of New York Communist Robert Sheldon Harte, executed[33] by one shot to the head. He had been one of Trotsky's bodyguards. The theory that Sheldon was a Soviet agent who had infiltrated Trotsky's entourage, aiding in Siqueiros' attack by allowing the hit squad to enter Trotsky's compound, was discounted by Trotsky and later historians.[34] Siqueiros's colleague Josep Renau completed the SME mural, transforming the generator into a machine that converts the blood of workers into coins.

Siqueiros was located by the police in a property supposedly rented by Angelica and Luis Arenal (Siqueiros's wife and brother-in-law respectively) in the outskirts of the capital. Siqueiros fled to Guadalajara, hiding in the house of his old friend José Guadalupe Zuno and from there he moved to the mountain town of Hostotipaquillo. Together with Angélia Arenal, he hid disguised as a peasant under the name of Macario Huízar. The Jalisco police apprehended Siqueiros and he was taken back Mexico City. He was formally processed and declared prisoner in the Lecumberri Preventive Prison. Siqueiros was charged for attempted homicide, criminal association, improper use of uniform, usurpation of functions, breaking and entering, firing a firearm and robbery.[29]

Despite Siqueiros's participation in these events, he never stood trial and was given permission to leave the country to paint a mural in Chile, arranged by Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. In a school library in the town of Chillán, he organized a team of artists to paint a mural which combined the heroic figures of Mexico and Chile in "Death to the Invader."

Hoping to revisit the United States and contribute to the struggle against fascism, he was denied entry and went to Cuba where he painted three murals, "Allegory of Racial Equality and Fraternity in Cuba," "New Day of the Democracies" and "Two Mountains of America, Marti and Lincoln."

Later life and works

In 1948, Siqueiros was invited to teach a course on mural painting at an art academy in San Miguel Allende. Although he was barred from the United States, most of the students were American GIs who were being paid to study under him. Practicing his idea of learning art by working with a master artist on a mural project, he planned a mural in a colonial building recognizing the legacy of Miguel Allende, one of Mexico's leaders of the struggle for independence. The mural was never completed, due to legal procedures against the owner of the art academy. Based on this experience, he later wrote a book Como se pinta un mural.

Siqueiros participated in the first ever Mexican contingent at the XXV Venice Biennale exhibition with Orozco, Rivera and Tamayo in 1950, and he received the second prize for all exhibitors, which recognized the international status of Mexican art.[35][36] Yet by the 1950s, Siqueiros returned to accepting commissions from what he considered a "progressive" Mexican state, rather than painting for galleries or private patrons.[36] He constructed an outdoor mural entitled The People to the University, the University to the People at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City in 1952. It was a combination of mural painting, bas-relief sculpture and Italian mosaic. In 1957 he began work on 4,500-square-foot (420 m2) government commission for Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City; Del porfirismo a la Revolución was his biggest mural yet.[36] (The painting is known in English as From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz to the Revolution or The Revolution Against the Porfirian Dictatorship.)

In the lobby of the Hospital de la Raza in Mexico City, he created a revolutionary multi-angular mural using new materials and techniques, For the Social Welfare of all Mexicans. After painting Man the Master and Not the Slave of Technology on a concave aluminum panel in the lobby of the Polytechnic Institute, he painted The Apology for the Future Victory of Science over Cancer on panels that wrap around the lobby of the cancer center.[35]

Yet near the end of the decade, his outspoken communist views alienated him from the government. Under pressure from the government, the National Actors' Association, which had commissioned a mural on the theater in Mexico suspended his work on The History of Theater in Mexico at the Jorge Negrete Theater and sued him for breach of contract in 1958.[37]

.jpg.webp)

Siqueiros was eventually arrested in 1960 for openly criticizing the President of Mexico, Adolfo López Mateos, and leading protests against the arrests of striking workers and teachers, though the charges were commonly known to be false.[35] Numerous protests ensued, even including an appeal advertisement by well-known artists and writers in The New York Times in 1961.[38] Unjustly imprisoned, Siqueiros continued to paint, and his works continued to sell.[36] During that stay, he would make numerous sketches for the project of decorating the Hotel Casino de la Selva, owned by Manuel Suarez y Suarez. After international pressure was put on the Mexican authorities, Siqueiros was finally pardoned and released in the spring of 1964. He immediately resumed working on his suspended murals in the Actors' Union and Chapultepec Castle.

When the mural planned for the Hotel de la Selva in Cuernavaca was moved to Mexico City and expanded, he assembled a team of national and international artists to work on the panels in his workshop in Cuernavaca.[35] This project, his last major mural, is the largest mural ever painted, an integrated structure combining architecture, in which the building was designed as a mural, with mural painting and polychromed sculpture. Known as the Polyforum Siqueiros, the exterior consists of 12 panels of sculpture and painting while the walls and ceiling of the interior are covered with The March of Humanity on Earth and Toward the Cosmos.[35] Completed in 1971 after years of extension and delay, the mural broke from some previous stylistic mandates, if only by its complex message. Known for making art that was easily read by the public, especially the lower classes, Siqueiros' message in The March is more difficult to decipher, though it seems to fuse two visions of human progress, one international and one based in Mexican heritage.[36] The mural's placement at a ritzy hotel and commission by its millionaire owner also seems to challenge Siqueiros' anti-capitalist ideology.[36]

Siqueiros died in Cuernavaca, Morelos, on January 6, 1974 in the company of Angélica Arenal Bastar, who had been his partner since the Spanish civil war. His body was buried in the Rotunda of Illustrious Persons in Mexico City.[39] A few days before his death, he donated his house in Polanco to the Mexican state; since 1969, it had been used for Public Art Rooms and a Museum of Mural Painting Composition.

Style

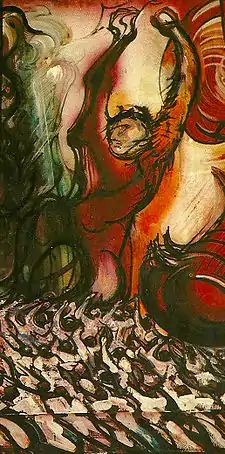

As a muralist and an artist, Siqueiros believed art should be public, educational, and ideological. He painted mostly murals and other portraits of the revolution – its goals, its past, and the current oppression of the working classes. Because he was painting a story of human struggle to overcome authoritarian, capitalist rule, he painted the everyday people ideally involved in this struggle. Though his pieces sometimes include landscapes or figures of Mexican history and mythology, these elements often appear as mere accessories to the story of a revolutionary hero or heroes (several works depict the revolutionary "masses", such as the mural at Chapultepec).[40]

His interest in the human form developed at the Academy in Mexico City. His accentuation of the angles of the body, its muscles and joints, can be seen throughout his career in his portrayal of the strong revolutionary body. In addition, many works, especially in the 1930s, prominently feature hands, which could be interpreted as another heroic symbol of proletarian strength through work: his self-portrait in prison (El Coronelazo, 1945, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City), Our Present Image (1947, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico), New Democracy (1944, Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City), and even his series on working class women, such as The Sob.

Gallery

Peasants (c. 1913)

Peasants (c. 1913) Tomb of David Alfaro Siqueiros in Panteón de Dolores

Tomb of David Alfaro Siqueiros in Panteón de Dolores Escultura Don Manuel Suarez and Siqueiros

Escultura Don Manuel Suarez and Siqueiros.jpg.webp) "Yo por Yo" self-portrait, David Alfaro Siqueiros, dedicated to Fernando Gamboa museographer and promoter of the Mexican art, August 1956.

"Yo por Yo" self-portrait, David Alfaro Siqueiros, dedicated to Fernando Gamboa museographer and promoter of the Mexican art, August 1956.

Major exhibitions

- Siqueiros, at Casino Español, Mexico City, 1932.[41]

- 70 Recent Works from David Alfaro Siqueiros, at the Museo Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Mexico City, 1947.[41]

- Siqueiros, at Galeria de Arte Mexicano, Mexico City, 1953.[41]

- Siqueiros: Retrospective Exhibition 1911–1967, at the Museo Universitario de Ciencas y Arte, Mexico City, 1967.[41]

- Siqueiros-Exposición Retrospectiva, at the Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, 1972.[41]

- Siqueiros: Exposción de Homenaje, at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, 1975.[41]

- Siqueiros-Visión, Tecnica y Estructural, at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, 1984.[41]

- Images of Mexico, at the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, 1988.[41]

- Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1993.[41]

- Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art 1925–1945, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2020.[42]

See also

- Mexican muralism

- Mexican art

- Museo Cabeza de Juárez

- La Tallera

- List of people from Morelos, Mexico

Selected other works

- Proletarian Mother, 1929, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico

- Zapata (lithograph), 1930, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

- Zapata (oil painting), 1931, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

- América Tropical, 1932, Los Angeles[20]

- War, 1939, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- José Clemente Orozco, 1947, Carillo Gil Museum, Mexico City

- Cain in the United States, 1947, Carillo Gil Museum, Mexico city

- For Complete Social Security of All Mexicans, 1953–36, Hospital de La Raza, Mexico City

Further reading

- Debroise, Olivier. Otras rutas hacia Siqueiros. Mexico City: INBA/Curare, 1996.

- Debroise, Olivier. So Far from Heaven: David Alfaro Siqueiros' "The March of Humanity" and Mexican Revolutionary Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- González Cruz Manjarrez, Maricela. La polémica Siqueiros-Rivera: Planteamientos estéticos-políticos 1934–35. Mexico City: Museo Dolores Olmedo Patriño, 1996.

- Harten, Jürgen. Siqueiros/Pollock: Pollock/Siequeiros. Düsseldorf: Kunsthalle, 1995.

- Jolly, Jennifer. "Art of the Collective: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Josep Renau, and their Collaboration at the Mexican Electricians' Syndicate." Oxford Art Journal 31 no. 1 (2008) 129–51.

- Portrait of a Decade: David Alfaro Siqueiros. Mexico City: MUNAL/INBA, 1997.

- Siqueiros, David Alfaro. "Rivera's Counter-Revolutionary Road." New Masses, May 29, 1934.

- Siqueiros: El lugar de la utopía. Exhibition catalogue, Mexico City: INBA and Sala de Arte Pública Siqueiros, 1994.

- Tamayo, Jaime. "Siqueiros y los orígenes del movimiento rojo en Jalisco: El movimiento minero." Estudios sociales 1, no. 1 (July–October 1984): 29–41.

- Tibol, Raquel. Siqueiros, vida y obra. Mexico City: Colección, 1973.

- Tibol, Raquel, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Shifra M. Goldman, and Agustín Arteaga. Los murales de Siqueiros. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1998.

Notes

- "Siqueiros Paintings, Bio, Ideas". The Art Story. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- The art story, life and legacy

- Conaculta 2011.

- Proceso 2004.

- Gente Sur 2005.

- Stein 1994, pp. 14–16.

- Stein 1994.

- "David Alfaro Siqueiros / Collective Suicide / 1936". MoMA. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Calles 1975, p. 21.

- Calles 1975.

- Laurance P. Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States (Albuquerque, N.M.: University of New Mexico Press, 1989), 203.

- Brenner, Anita (1929). Idols Behind Altars. New York: Payson & Clark Ltd. pp. 244–59.

- D. Anthony White (2009). Siqueiros: Biography of a Revolutionary Artist. Booksurge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4392-1172-4.

- Hurlburt, Laurance (1989). The Mexican Muralists in the United States. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 210–13. ISBN 0826311342.

- Del Barco, Mandalit. Revolutionary Mural To Return To L.A. After 80 Years. npr. October 26, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Hurlburt, Laurance (1989). The Mexican Muralists in the United States. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 213. ISBN 0826311342.

- "Conservation of América Tropical" The Getty Conservation Institute website Accessed 14 November 2014

- Whalen, Timothy P. (October 9, 2012) "América Tropical Is Reborn on 80th Birthday" The Getty Iris The J. Paul Getty Trust

- América Tropical Interpretive Center Official website

- "'America Tropical': A forgotten Siqueiros mural resurfaces in Los Angeles". Los Angeles Times. September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-02-06.

- Ruth Green Harris, "Art That Is Now Being Shown In the Galleries," The New York Times, December 7, 1930.

- Karlstrom, Paul J. (1996). On the edge of America: California Modernist Art 1900–1950. Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press. p. 130.

- Lucie-Smith 2004, p. 63.

- Langa, Helena. Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-520-23155-9. p. 234.

- Hurlburt, Laurance (1976). "The Siqueiros Experimental Workshop: New York, 1936". Art Journal. 35 (3): 237–46. doi:10.1080/00043249.1976.10793284. JSTOR 775942.

- Jolly, Jennifer (2009). "The Art of the Collective". Oxford Art Journal. 31 (1): 129–51. doi:10.1093/oxartj/kcn006.

- Rolfe, Edwin, Cary Nelson, and Jefferson Hendricks. Trees Became Torches: Selected Poems. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995. p. 146

- Rolfe, Edwin, Cary Nelson, and Jefferson Hendricks. Trees Became Torches: Selected Poems. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995. p. 85

- Cabrera Nuñez, Eduardo César; Valentina de Santiago Lázaro, María (2007). Siqueiros. Cronología biográfica. Ayuntamiento de Guanajuato.

- "The artist as activist: David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974)". Mexconnect.com. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Mike Lanchin (28 August 2012). "Trotsky's grandson recalls ice pick killing". BBC News. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

Volkov was hit in the foot

- Ted Crawford; David Walters, eds. (May 1942). "The Murder of Robert Sheldon Harte". Fourth International. 3 (5): 139–42. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

a month later, on June 25th, Bob's lime-covered body was found in a shallow grave

- "Index and Concordance to Alexander Vassiliev's Notebooks and Soviet Cables Deciphered by the National Security Agency's Venona Project" (PDF). Wilson Center. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 1 November 2014. pp. 175–76. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

Harte left alive with the raiders but was found dead a few days later.

- Robert Service. Trotsky: A Biography. Belknap Press. 2009. p. 485-488

- Siqueiros, Biography of a Revolutionary Artist, (Book Surge, 2009)

- Leonard Folgarait, So Far From Heaven: David Alfaro Siqueiros' The March of Humanity and Mexican Revolutionary Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 36.

- Bruce Campbell, Mexican Murals in Times of Crisis (Tucson, Ariz.: The University of Arizona Press, 2003), 54.

- "Siqueiros" (advertisement), The New York Times, August 9, 1961.

- "Rotonda de las personas ilustres". rotonda.segob.gob.mx. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Carolyn Hill, ed., Mexican Masters: Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma City Museum of Art, 2005), 80.

- Stein 1994, pp. 380–81.

- "Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945". whitney.org. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

References

- David Alfaro Siqueiros, art and revolution. Translated by Calles, Sylvia. London: Lawrence & Wishart. 1975.

- "David Alfaro Siqueiros, un artista cuya obra ha trascendido el tiempo y las fronteras". Conaculta (Government of Mexico, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes) Press release no. 26 (in Spanish). 2011-01-06.

- "El verdadero Origen de Siqueiros; lo que hay de cierto tras el mito del Coronelazo" [Siqueiros's true origin: the reality behind the myth of the Big Colonel]. Gente Sur (in Spanish). 2005-10-15. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (2004). Latin American Art of the 20th Century (2nd ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson.

- "Buscan fondos para la restauración del Polyforum" [Funds sought for the restoration of the Polyforum]. Proceso (in Spanish). 2010-12-28.

- Stein, Philip (1994). Siqueiros: His Life and Works. New York: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0709-6.

External links

- Siqueiros at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- Lne.es

- The Polyforum, Mexico City

- Siqueiros on Artcyclopedia.com

- Siqueiros Image Bank (collection of photographs used by Siquieros for his work)

- Finding Aid for the David Alfaro Siqueiros papers at the Getty Research Institute

- Ten Dreams Galleries

- Mexico Info Profile (in Spanish)

- Figureworks.com/20th Century work at www.figureworks.com