David Bowie (1967 album)

David Bowie is the debut studio album by English musician David Bowie. It was released in the United Kingdom on 1 June 1967 through Decca-subsidiary Deram Records. Following a string of singles that failed to chart and being dismissed from Pye Records in late 1966, Bowie was signed to Deram on the strength of "Rubber Band". After spending autumn of that year writing songs, David Bowie was recorded from November 1966 to March 1967 at Decca Studios in London with production by Mike Vernon, who hired numerous studio musicians. Bowie and his former Buzz bandmate Derek "Dek" Fearnley composed music charts for the orchestra using Freda Dinn's Observer's Guide to Music.

| David Bowie | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 1 June 1967 | |||

| Recorded | 14 November 1966 – 1 March 1967 | |||

| Studio | Decca, London | |||

| Genre | Baroque pop, music hall | |||

| Length | 37:07 | |||

| Label | Deram | |||

| Producer | Mike Vernon | |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from David Bowie | ||||

| ||||

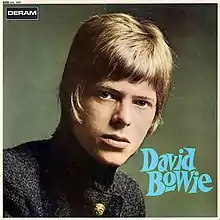

Musically, the album displays a baroque pop and music hall sound influenced by Anthony Newley and the Edwardian styles of contemporary British rock bands. The songs are primarily led by orchestral brass and woodwind instruments rather than traditional instruments in pop music at the time, although some tracks feature guitar. The lyrics are short-story narratives that range from lighthearted to dark, discussing themes from childhood innocence, to drug use and totalitarianism. Bowie utilised various ideologies on the record for his later works. The cover artwork is a headshot of Bowie in a mod haircut wearing a high-collared jacket.

Released in both mono and stereo, David Bowie received positive reviews from music journalists but was a commercial failure due to a lack of promotion from Deram. Two tracks were omitted for its release in the United States in August 1967. Bowie provided more tracks for Deram, all of which were rejected and led to his departure from the label. Retrospective reviews have unfavourably compared David Bowie to the artist's later works, but some have recognised it positively on its own terms. The album was reissued in a two-disc deluxe edition in 2010, which featured both mixes and other tracks from the period.

Background

Following a string of singles that failed to chart, David Bowie was let go from Pye Records in September 1966.[1] The lack of promotion from Pye also contributed to Bowie's disenchantment with the label.[2] In order to secure him a new record contract, his soon-to-be manager Kenneth Pitt financed a recording session the next month at London's R G Jones Studio.[3] On 18 October, Bowie and his backing band the Buzz conducted a four-hour session with a group of local studio musicians, producing a new version of the rejected Pye track "The London Boys" and two new songs, "Rubber Band" and "The Gravedigger".[1][2] Two days after the session, Pitt showed an acetate of "Rubber Band" to the promotional head of Decca Records, Tony Hall, who was impressed and was eager to hear more, later reflecting: "I must say I did flip. This guy had such a different sound, such a different approach."[4]

Six days after the session on 24 October, Pitt showed acetates of all three tracks to Decca A&R manager Hugh Mendl and in-house producer Mike Vernon, who were both impressed. Mendl signed Bowie to the label's progressive pop subsidiary label Deram Records and gave him a deal that financed the production of a full-length album and paid £150 for the three tracks and a further advance of £100 for royalties on the album. At the time, being granted an album deal before having a hit single was a rare occurrence.[2][4] Mendl later stated: "I had a minor obsession about David—I just thought he was the most talented, magical person. ... I think I would have signed him even if he didn't have such obvious musical talent. But he did have talent. He was bursting with creativity."[3]

Writing and recording

.jpg.webp)

Bowie spent the autumn of 1966 writing songs; at one point, he and Pitt had counted almost 30 new compositions. According to biographer Paul Trynka, his songwriting focused less on traditional instrumentation and more in favour of orchestral arrangements, in the vein of the Beach Boys' recently-released Pet Sounds.[3] The album sessions officially commenced on 14 November at Decca Studio 2 in West Hampstead, London with the recording of "Uncle Arthur" and "She's Got Medals".[2] Vernon produced the entirely of the sessions while Gus Dudgeon engineered.[5] The Buzz contributed with the exception of keyboardist Derek Boyes, who had "suspect appendicitis".[6]

We didn't realise how ludicrous [the scores] must have looked. I guess it was just the audacity of it that none of the guys laughed us out of the studio. They actually tried to play our parts and they made sense of them. They're quite nice little string parts – we were writing for bassoon and everything. If Stravinsky can do it, then we can do it![7]

—David Bowie, 1993

Rather than hire an arranger, Bowie and Buzz member Derek "Dek" Fearnley used Freda Dinn's Observer's Guide to Music to study orchestra arrangements and requested Vernon hire the appropriate musician. Because Fearnley had little experience writing music charts, while Bowie couldn't read music at all, he found it a daunting task, later stating: "It was bloody hard work. I knew how to read the staves and that a bar had four crotches; David had never seen or written a note, so I was the one qualified to write stuff out."[5][3] He found that when presenting the charts to the musicians, some of whom were members of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, they threw them back and requested new scores, which he had to do himself while Bowie monitored from the control room.[2][3][6]

Recording continued on 24 November 1966, when "There Is a Happy Land", "We Are Hungry Men", "Join the Gang" and the B-side "Did You Ever Have a Dream" were completed.[2] Around the same time, Pitt and Bowie's current manager Ralph Horton decided that Bowie would cease live performances so he could focus on recording the album and that he would part ways with the Buzz. Bowie and the Buzz made their final live performance together on 2 December, the same day Deram issued the "Rubber Band" single. Recording continued on, with "Sell Me a Coat", "Little Bombardier", "Silly Boy Blue" and "Maid of Bond Street" tracked from 8 to 9 December, with "Come and Buy My Toys" and "The Gravedigger", now titled "Please Mr. Gravedigger", following on 12 and 13 December, respectively.[2][6]

Alongside the Orchestra members, Vernon hired numerous uncredited sessions musicians, some of which included guitarist John Renbourn, whose playing is heard prominently on "Come and Buy My Toys", and multi-instrumentalist Big Jim Sullivan, who contributed banjo on "Did You Ever Have a Dream" and sitar on "Join the Gang". In December, Fearnley's friend Marion Constable contributed backing vocals on "Silly Boy Blue".[2] Later on, Vernon recalled having "a lot of fun" during the sessions and described Bowie as "the easiest person to work with", further adding that "some of the melodies were extremely good, and the actual material, the lyrics, had a quality that was quite unique."[2] This sentiment was echoed by Dudgeon, who told biographer David Buckley that "the music was very filmic, all very visual and all quite honest and unaffected and therefore unique."[8]

A provisional running order was drawn up at the end of December 1966, which saw the inclusion of tracks that would be removed from the final album, such as "Did You Ever Have a Dream", "Your Funny Smile" and "Bunny Thing". In mid-January 1967, Bowie fired Horton as his manager after months of financial mismanagement and approached Pitt, who took over as his full-time manager in April.[2] On 26 January, Bowie and the musicians reconvened at Decca, recording the backing tracks for "The Laughing Gnome" and "The Gospel According to Tony Day", which were chosen as the next single; vocals were added in early February.[9] On 25 February, a new version of "Rubber Band" was recorded for inclusion on the album, as well as "Love You till Tuesday" and "When I Live My Dream". These tracks featured uncredited arrangements by Arthur Greenslade. Final touches were added on 1 March, completing the sessions. The album was mixed in both mono and stereo,[9] making David Bowie one of the first albums to be released in both formats. According to biographer Nicholas Pegg, the two variants featured minor differences in instrumentation and mixing:[2] mono editions used slightly different mixes of "Uncle Arthur" and "Please Mr. Gravedigger".[10]

Style and themes

Lyrically, I guess it was striving to be something, the short story teller. Musically it's quite bizarre. I don't know where I was at. It seemed to have its roots all over the place, in rock and vaudeville and music hall. I didn't know if I was Max Miller or Elvis Presley.[2]

—David Bowie on the album, 1990

David Bowie consists of 14 tracks, all of which were written entirely by Bowie himself.[7] His influences at this stage of his career included the theatrical tunes of Anthony Newley, music hall numbers by acts like Tommy Steele, whimsical British material by Ray Davies of the Kinks, Syd Barrett's psychedelic nursery rhymes for the early Pink Floyd, and the Edwardian flair shared by the contemporary works of the Kinks and the Beatles.[8] The desire of Pitt for Bowie to become an "all-around entertainer" rather than a "rock star" also impacted the songwriter's style.[11] As such, the songs range from up-tempo pop, rock and waltz.[12] BBC Music retrospectively categorised it as baroque pop and music hall.[13] Rather than using traditional instruments in pop music at the time, such as guitar, piano, bass and drums, the instruments on David Bowie likened to those in music hall and classical music, such as brass instruments (tuba, trumpet and French horn) and woodwind instruments (bassoon, oboe, English horn and piccolo).[12] Biographer David Buckley notes almost an entire absence of lead guitar in the final mix.[8]

Tracks such as "Rubber Band", "Little Bombardier" and "Maid of Bond Street" are primarily led by brass instruments,[8] while "Uncle Arthur" and "She's Got Medals" are primarily led by woodwinds.[14] "Little Bombardier" and "Maid of Bond Street" are in waltz time,[8] while "Join the Gang" includes sitar and a musical quotation of the Spencer Davis Group's recent hit "Gimme Some Lovin'".[15] The Newley influence is present on "Love You till Tuesday", "Little Bombardier" and "She's Got Medals".[2][5] Regarding the influence, Newley himself later stated in 1992: "I always made fun of it, in a sense. Most of my records ended in a stupid giggle, trying to tell people that I wasn't being serious. I think Bowie liked that irreverent thing, and his delivery was very similar to mine, that Cockney thing. But then he went on to become madly elegant and very, very original."[7]

"Love You till Tuesday" and "Come and Buy My Toys" are among the few songs on the album with an acoustic guitar, the former heavily augmented by strings.[16] The latter, in particular, is noted by O'Leary as more minimalist in nature,[5] and exemplifies folk in a way author Peter Doggett likens to Simon & Garfunkel.[17] Described by Buckley as "one of pop's genuinely crazy moments",[8] "Please Mr. Gravedigger" utilises various studio sound effects and no backing instrumentation. Biographers compare it to a radio play from the 1940s and 1950s and consider it a comedic parody of the old British song "Oh! Mr Porter".[5][18]

Like the music, the lyrical themes are widespread, ranging from lighthearted, to dark, to funny to sarcastic. Additionally, the characters range from societal outcasts, to losers, "near-philosophers" and dictators.[12] According to biographer Chris O'Leary, David Bowie found Bowie composing third-person narratives compared to the first-person love stories of his previous releases,[5] a statement echoed by Kevin Cann, who likens the song narratives to traditional folk stories.[7] In 1976, Bowie commented that "the idea of writing sort of short stories, I thought was quite novel at the time".[5] Mark Spitz writes that it contains several "vaguely dark, arcane English story songs" ("Please Mr. Gravedigger", "Uncle Arthur", "Maid on Bond Street") that Pitt envisioned Bowie performing in lounges.[19] "Rubber Band", "Little Bombardier" and "She's Got Medals" all evoke the Edwardian theme.[7]

Lighthearted themes, such as childhood innocence, are celebrated in "Sell Me a Coat", "When I Live My Dream" and "Come and Buy My Toys",[7] as well as the psychedelic-influenced "There Is a Happy Land", which took its title and subject matter from the Andrew Young hymn of the same name.[5][20] "Silly Boy Blue" expresses Bowie's then-recent interest in Buddhism.[21] On the other hand, "Join the Gang" discusses darker ideals such as peer pressure and drug use,[16] while "We Are Hungry Men" depicts a totalitarian world that reflects messianic worship and cannibalism in a comedic way.[22][23] Meanwhile, "Little Bombardier" concerns a war veteran who is forced to leave town after being suspected for pedophilia,[12] and the a cappella "Please Mr. Gravedigger" details a child-murderer contemplating his next victim while standing in a graveyard.[5][8][18]

Release

.png.webp)

David Bowie was released in the United Kingdom on 1 June 1967, with the catalogue numbers DML 1007 (mono) and SML 1007 (stereo).[2] Its release coincided with the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[24][25][26] The American release, issued in August 1967, omitted "We Are Hungry Men" and "Maid of Bond Street", which Pegg speculates was possibly due to the US practice of trimming track listings in order to "reduce publishing royalties".[2]

The sleeve photograph is a full-headshot of Bowie in a mod haircut wearing a high-collared jacket. The sleeve was taken by Fearnley's brother Gerald in his basement studio near Marble Arch, where Bowie and Dek Fearnley had conducted rehearsals for the sessions. Bowie himself chose the jacket and later recalled that he was "very proud" of it, stating "it was actually tailored".[2] Spitz considers the image "very rooted" in the mid-1960s,[19] and Consequence of Sound's Blake Goble called it "perhaps the most uninteresting and dated album cover of Bowie's career" in 2018.[27] The Pitt-written sleeve notes also described Bowie's vision as "straight and sharp as a laser beam. It cuts through hypocrisy, prejudice and cant. It sees the bitterness of humanity, but rarely bitterly. It sees the humour in our failings, the pathos of our virtues."[2]

Despite promotional attempts by other countries outside the UK and US,[7] David Bowie was a commercial failure, in part due to lack of promotion from Deram. The label were already unimpressed with the "Rubber Band" single and after Tony Hall, who was instrumental in Bowie's signing, departed the company in May 1967, it was apparent they had no interest in promoting.[2][28] Vernon later stated that Decca "didn't understand what rock music was ... at all".[8] Additionally, both "The Laughing Gnome", issued in April, and a new version of "Love You till Tuesday", recorded on 3 June and issued on 14 July,[29] saw no chart success neither, further signaling Bowie's downturn with the label.[2][19]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

David Bowie received few reviews from music critics on release, although the ones it did receive were positive.[2] In New Musical Express, Allan Evans praised the record as "all very refreshing" and called the artist "a very promising talent. And there's a fresh sound to the light musical arrangements by David and Dek Fearnley."[2] A reviewer for Disc & Music Echo described the album as "a remarkable, creative debut album by a 19-year-old Londoner," further declaring: "Here is a new talent that deserves attention, for though David Bowie has no great voice, he can project words with a cheeky 'side' that is endearing yet not precious ... full of abstract fascination. Try David Bowie. He's something new."[2][35] The journalist also suggested that Bowie could garner more attention if he "gets the breaker and the right singles".[36] After Pitt sent copies of David Bowie to several music executives in order to generate publicity, he received letters of admiration from Lionel Bart, Bryan Forbes and Franco Zeffirelli.[2]

Retrospective reviews of David Bowie have been mixed, with many comparing it unfavourably to Bowie's later works. Writing for AllMusic, Dave Thompson called it "an intriguing collection, as much in its own right as for the light it sheds on Bowie's future career" and concluded that "though this material has been repackaged with such mind-numbing frequency as to seem all but irrelevant today, David Bowie still remains a remarkable piece of work. And it sounds less like anything else he's ever done than any subsequent record in his catalog."[30] The same publication's Stephen Thomas Erlewine noted that although the record does not provide a good indication of Bowie's future works, on its own it remains "a fascinating, highly enjoyable debut".[37] Reviewing in 2010, BBC Music's Sean Egan found an "unrefined" talent in Bowie, noting "above average" lyrics that are "hardly deep". Nevertheless, he praised Bowie's commitment to the project, concluding that "David Bowie is hardly an essential listen but historically interesting as unmistakably the entrée of someone with a future."[13] In 2017, Dave Swanson of Ultimate Classic Rock commented that while the music was joyful, the record was out of place with the music industry at the time, which he argued mostly contributed to its failure.[26]

Subsequent events

Bowie went on to record several tracks for Deram, all of which were rejected by the label.[2] In September 1967, Bowie recorded "Let Me Sleep Beside You" and its B-side "Karma Man", which marked the beginning of the artist's association with producer Tony Visconti. Both tracks had a radically different sound to the material on David Bowie, harking back to his pre-Deram mod period. Despite this, Deram refused to release the single, which Pegg saw as possibly due to the suggestive nature of the A-side's title.[38][39][40] Bowie quickly proposed swapping the A-side with a new version of "When I Live My Dream", which had been re-recorded in the same session as his third post-album single. Once again Deram refused to release the track, possibly because they felt the sound of this material had failed so many times before.[41] In early 1968, Bowie recorded another two tracks for release as a single: "In the Heat of the Morning" and "London Bye Ta–Ta". Resembling the pop-mod sound of "Let Me Sleep Beside You", "In the Heat of the Morning" was again rejected by Deram.[42]

The failure of David Bowie and its singles, as well as not being able to produce anything with his subsequent material felt worthy of release, resulted in Bowie's departure from Deram in May 1968.[2] Outside of music, Bowie starred in the Michael Armstrong-directed short film The Image (1969), which fell into obscurity until 1973.[43][44][45] Additionally, Bowie became associated with mime actor Lindsay Kemp, who was a fan of David Bowie. He acted in the Kemp's mime play Pierrot in Turquoise throughout early 1968, where he performed the David Bowie songs "When I Live My Dream", "Sell Me a Coat" and "Come and Buy My Toys".[44] Bowie returned to music in late 1968 with the folk rock group Feathers, consisting of himself, dancer Hermione Farthingale and guitarist John Hutchinson. They recorded a single track, "Ching-a-Ling", before splitting in 1969.[46][47]

After the commercial failure of David Bowie, Pitt authorised a promotional film in an attempt to introduce Bowie to a larger audience. The film, Love You till Tuesday, marked the end of Pitt's mentorship of Bowie and went unreleased until 1984.[48] Knowing Love You till Tuesday wouldn't feature any new material, Pitt asked Bowie to write something new.[49] Encompassing the feeling of alienation, he wrote "Space Oddity", a tale about a fictional astronaut named Major Tom.[50] Eighteen months after David Bowie's release, "Space Oddity" became the artist's first hit.[2][51]

Legacy

I wouldn't say that we struggled, but it was an adventure. I wasn't sure what to make of [the album] at the time or if it was even commercial, but as usual, I just put all my likes and dislikes aside and got on with it. It was a very, very quirky one-off record and ideal for Deram.[7]

—Mike Vernon, 2009

David Bowie, and the Deram period in general, were routinely mocked throughout Bowie's career, being dismissed, in Pegg's words, as "music-hall piffle derived from a passing Anthony Newley fad",[2] a characteristic noted by Gus Dudgeon, who later told Buckley, "it bothered Mike Vernon and me because we'd say, 'Bowie's really good and his songs are fucking great, but he sounds like Anthony Newley'."[8] Buckley himself ridiculed David Bowie as a "cringe-inducing piece of juvenilia" only to be braved by "those with a high enough embarrassment threshold".[8] Bowie himself downplayed or disowned the period entirely, calling it "cringey" in 1990.[2] According to Pegg, Bowie's fans have attempted to place blame on Pitt for the record's sound, a theory the manager dismissed in his memoir, stating that it was Bowie's sole idea to "sound like Newley". Pegg also rejects this claim, as Pitt was absent from Bowie's person during the majority of the writing and recording period.[2]

Other claims made about David Bowie include the idea that it sounded like nothing else at the time,[26] which Pegg attributes to Dudgeon's "oft-quoted" description of the album as "about the weirdest thing any record company have ever put out".[2] Pegg debunks this idea, writing that David Bowie's blend of "folk and short-story narrative" shared similarities with the more commercial releases of the British psychedelia movement of 1966–1967 and that numerous motifs throughout the album, such as wartime nostalgia and childhood innocence, reflected the contemporary ideals of Syd Barrett's Pink Floyd, the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and the Beatles.[2] The Beatles, in particular, embellished similar ideas as David Bowie into their recent records Revolver (1966) and Sgt. Pepper: the latter's "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!" matched the waltz-style of "Little Bombardier", while Pegg compares the styles of "Uncle Arthur", "She's Got Medals" and "Sell Me a Coat" to "Eleanor Rigby", "Lovely Rita" and "She's Leaving Home".[2] Additionally, Buckley writes that Bowie's use of brass and woodwinds on "Rubber Band" predated their use by the Beatles' on Sgt. Pepper,[8] while Doggett further writes that "Rubber Band" and "With a Little Help from My Friends" both feature lyrical gags about performing "out of tune".[52]

Regarding the blend of folk, pop and classical, Perone argues that the Moody Blues' Days of Future Passed, also released by Deram in 1967, was more commercially viable but displayed the combination, sometimes to greater effect, on David Bowie, particularly on "Rubber Band" and "Sell Me a Coat".[12] Comparing Bowie to the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, Pegg states that the Bonzos' debut single "My Brother Makes the Noises for the Talkies" contained sound effects that Bowie utilised for "We Are Hungry Men", "Please Mr. Gravedigger" and the outtake "Toy Soldier", and later "Ching-a-Ling".[2]

Commentators have noted themes on David Bowie that would inform the artist's later work.[16][8] "We Are Hungry Men" is told by a self-styled messiah whose persona would reappear in different forms in works throughout his entire career.[2] Perone further argues that the track anticipated the post-punk and new wave styles of the late 1970s, naming Talking Heads' first and second albums.[12] Additionally, the folk of "Come and Buy My Toys" anticipated Bowie's exploration of the genre on his second self-titled album in 1969,[2] while Doggett finds the sense of desperation on "Rubber Band" predated the Station to Station (1976) and "Heroes" LPs (1977).[52] Biographers also contend that the gender-bending themes of "She's Got Medals" predated 1971's "Queen Bitch" and 1974's "Rebel Rebel".[5][8]

David Bowie justifiably resides in the shadow of [Bowie's] later work, but those with open ears and open minds know it as a sweet, clever album that has borne decades of derision with consummate dignity.[2]

—Nicholas Pegg, The Complete David Bowie, 2016

Bowie's biographers have held mixed opinions on David Bowie. NME critics Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray have said, "a listener strictly accustomed to David Bowie in his assorted '70s guises would probably find this debut album either shocking or else simply quaint",[16] while Buckley describes its status in the Bowie discography as "the vinyl equivalent of the madwoman in the attic".[8] Perone finds the debut showcases the artist displaying a wide variety of musical styles "generally to good effect".[12] Trynka praises Bowie's confidence and highlights individual tracks, such as "We Are Hungry Men" and "Uncle Arthur", but notes that he lacked ambition and commerciality at the time.[53] Doggett similarly contends that its "whimsical character studies" stood against the "psychedelic ambiance" of the era.[36] Pegg writes that "it seems a pity that David Bowie is only ever considered in terms of what we can extrapolate from it ... Thankfully, it does seem that pop musicologists are at last beginning to regard David Bowie not just as a quirky set of embryonic twitterings, but as an album that's actually worth considering in its own right."[2]

In a 2016 list ranking Bowie's studio albums from worst to best, Bryan Wawzenek of Ultimate Classic Rock placed David Bowie at number 23 (out of 26), criticising Bowie's vocal performances, lyrics and overall sound that lacks "wit and energy".[54] Including Bowie's two albums with Tin Machine, the writers of Consequence of Sound ranked David Bowie number 26 (out of 28) in their 2018 list. Goble called it "an awkward artifact", representing signs of what was to come for the artist but as a standalone album, it remains "not essential".[27]

Reissues and compilations

| Deluxe edition | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Classic Rock | |

| The Guardian | |

| Record Collector | |

| Rolling Stone | |

Bowie's Deram recordings have been recycled in a multitude of compilation albums, including The World of David Bowie (1970), Images 1966–1967 (1973), Another Face (1981), Rock Reflections (1990), and The Deram Anthology 1966–1968 (1997).[59]

Deram first reissued David Bowie on LP in August 1984, followed by a CD release in April 1989.[60] In January 2010, Deram and Universal Music reissued the album in a remastered two-disc deluxe edition package. Containing 53 total tracks, the deluxe edition compiles both the original mono and stereo mixes, Bowie's other Deram recordings, such as "The London Boys" and "The Laughing Gnome", single mixes, previously unreleased stereo mixes, alternate takes and for the first time, Bowie's first BBC radio session (Top Gear, December 1967).[37][57][61] The tracks were remastered by Peter Mew and Tris Penna, who previously undertook Virgin's deluxe reissue of Space Oddity. Penna stated in the deluxe edition liner notes that they wanted "to ensure [the tracks] sounded as good, if not better, than when they were first released".[62]

Reviewing the deluxe edition for The Second Disc, Joe Marchese considered it a welcome supplement to The Deram Anthology 1966–1968 that showed Bowie had talent but lacked direction. He concluded that the set allows listeners to reexamine David Bowie and "makes the best possible case for this 'lost era' of Bowie history".[62] Pegg similarly called the set "excellent".[2] Barry Walters of Rolling Stone described the collection as an "early portrait of pop's ultimate shape-shifter".[58] Erlewine praised the addition of the new tracks, arguing that they enhance the debut rather than diminish it, fully offering more insight into Bowie's talent at this stage of his career.[37] On the other hand, Egan found that while the collection was "comprehensive", it is also "aesthetically too much even if the parent album was the greatest ever made".[13]

Track listing

Two versions were released on LP in the UK: mono and stereo. Mono editions use slightly different mixes of "Uncle Arthur" and "Please Mr. Gravedigger". The American release omits "We Are Hungry Men" and "Maid of Bond Street".[2]

All tracks are written by David Bowie.

Side one

- "Uncle Arthur" – 2:07

- "Sell Me a Coat" – 2:58

- "Rubber Band" – 2:17

- "Love You till Tuesday" – 3:09

- "There Is a Happy Land" – 3:11

- "We Are Hungry Men" – 2:59

- "When I Live My Dream" – 3:22

Side two

- "Little Bombardier" – 3:23

- "Silly Boy Blue" – 4:36

- "Come and Buy My Toys" – 2:07

- "Join the Gang" – 2:17

- "She's Got Medals" – 2:23

- "Maid of Bond Street" – 1:43

- "Please Mr. Gravedigger" – 2:35

Personnel

According to biographers Kevin Cann and Nicholas Pegg:[2][7]

- David Bowie – vocals, guitar, arrangements

- Big Jim Sullivan – guitar, banjo, sitar (11)

- Derek Boyes – organ

- Derek "Dek" Fearnley – bass, arrangements

- John Eager – drums

- Marion Constable – backing vocals (9)

- Arthur Greenslade – arrangements (3, 4, 7)

Technical

- Mike Vernon – producer

- Gus Dudgeon – engineer

- Gerald Fearnley – cover photography

References

- Cann 2010, pp. 88–89.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 328–333.

- Trynka 2011, pp. 80–83.

- Cann 2010, pp. 90–91.

- O'Leary 2015, chap. 2.

- Cann 2010, pp. 92–93.

- Cann 2010, pp. 104–107.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 28–36.

- Cann 2010, pp. 99–100.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 212, 291.

- Pegg 2016, p. 253.

- Perone 2007, pp. 6–11.

- Egan, Sean (2010). "David Bowie – David Bowie (Deluxe Edition) Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 420–421.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 423–424.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 21–25.

- Doggett 2012, p. 429.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 211–212.

- Spitz 2009, pp. 76–78.

- Pegg 2016, p. 279.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 243–244.

- Pegg 2016, p. 303.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 422–423.

- Trynka 2011, p. 87.

- Wolk, Douglas (1 June 2016). "Remembering the Debut Album David Bowie Tried to Forget". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Swanson, Dave (2 June 2017). "Why David Bowie's Debut Didn't Sound Anything Like David Bowie". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Goble, Blake; Blackard, Cap; Levy, Pat; Phillips, Lior; Sackllah, David (8 January 2018). "Ranking: Every David Bowie Album From Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Cann 2010, pp. 93–94.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 175–176.

- Thompson, Dave. "David Bowie – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "David Bowie – Blender". Blender. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- "David Bowie: David Bowie". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 29 May 2003. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Cann 2010, pp. 108–109.

- Doggett 2012, p. 47.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "David Bowie [Deluxe Edition] – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Pegg 2016, p. 157.

- Trynka 2011, p. 93.

- Spitz 2009, pp. 83–86.

- Pegg 2016, p. 306.

- Pegg 2016, p. 132.

- Spitz 2009, pp. 78–79.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 653–655.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 48–49.

- Trynka 2011, pp. 102–104.

- Sandford 1997, p. 46.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 333, 636–638.

- O'Leary 2015, chap. 3.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 255–260.

- Spitz 2009, p. 108.

- Doggett 2012, pp. 414–417.

- Trynka 2011, p. 481.

- Wawzenek, Bryan (11 January 2016). "David Bowie Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Dee, Johnny (March 2010). "David Bowie – David Bowie (Deluxe Edition)". Classic Rock. No. 142. p. 95.

- Petridis, Alexis (14 January 2010). "David Bowie: David Bowie (Deluxe Edition)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Draper, Jason (15 January 2010). "David Bowie: Deluxe Edition – David Bowie". Record Collector. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Walters, Barry (5 April 2010). "David Bowie: Deluxe Edition". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 330, 500–505.

- Pegg 2016, p. 328.

- Pegg 2016, p. 509.

- Marchese, Joe (3 April 2010). "Review: David Bowie – David Bowie Deluxe Edition". The Second Disc. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

Sources

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croydon, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-9552017-7-6.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-380-77966-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York City: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99245-3.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03225-4.

External links

- David Bowie at Discogs (list of releases)