Dikembe Mutombo

Dikembe Mutombo Mpolondo Mukamba Jean-Jacques Wamutombo[2] (born June 25, 1966) is a Congolese-American former professional basketball player. Mutombo played 18 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Outside basketball, he has become well known for his humanitarian work.[3]

Mutombo in 2012 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 25, 1966 Kinshasa, Congo-Kinshasa |

| Nationality | Congolese / American |

| Listed height | 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) |

| Listed weight | 260 lb (118 kg)[1] |

| Career information | |

| High school | Institute Boboto (Kinshasa, DR Congo) |

| College | Georgetown (1988–1991) |

| NBA draft | 1991 / Round: 1 / Pick: 4th overall |

| Selected by the Denver Nuggets | |

| Playing career | 1991–2009 |

| Position | Center |

| Number | 55 |

| Career history | |

| 1991–1996 | Denver Nuggets |

| 1996–2001 | Atlanta Hawks |

| 2001–2002 | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 2002–2003 | New Jersey Nets |

| 2003–2004 | New York Knicks |

| 2004–2009 | Houston Rockets |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career NBA statistics | |

| Points | 11,729 (9.8 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 12,359 (10.3 rpg) |

| Blocks | 3,289 (2.8 bpg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

The 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m), 260-pound (120 kg) center, who began his career with the Georgetown Hoyas, is commonly regarded as one of the greatest shot blockers and defensive players of all time, winning the NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award four times; he was also an eight-time All-Star. On January 10, 2007, he surpassed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as the second most prolific shot blocker in NBA history, behind only Hakeem Olajuwon, and he averaged a double-double for most of his career.[4][5]

At the conclusion of the 2009 NBA playoffs, Mutombo announced his retirement. On September 11, 2015, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.[6]

Early life

Mutombo was born on June 25, 1966, in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, as one of 10 children to Samuel and Biamba Marie Mutombo.[7][8][9] His father worked as a school principal and then in Congo's department of education.[10] Mutombo speaks English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and five Central African languages, including Lingala and Tshiluba.[11][12] He is a member of the Luba ethnic group.[13] For high school, Mutombo went to Boboto College in Kinshasa to lay the groundwork for his medical career as the classes were more challenging there. He played football and participated in martial arts.[10] At around age 16, Mutombo decided to also work on his basketball career at the encouragement of his father and brother due to his height.[10][14] He moved to the United States in 1987 at the age of 21 to enroll in college.[15]

College

Mutombo attended Georgetown University on a USAID scholarship. He originally intended to become a doctor, but the Georgetown Hoyas basketball coach John Thompson recruited him to play basketball.[16][17] He spoke almost no English when he arrived at Georgetown and studied in the ESL program.[18][19] During his first year of college basketball as a sophomore, Mutombo once blocked 12 shots in a game.[20] Building on the shot-blocking power of Mutombo and teammate Alonzo Mourning, Georgetown fans created a "Rejection Row" section under the basket, adding a big silhouette of an outstretched hand to a banner for each shot blocked during the game.[21][22] Mutombo was named the Big East Defensive Player of the Year twice, in 1990 (shared with Mourning) and in 1991.[23]

At Georgetown, Mutombo's international background and interests stood out. Like many other Washington-area college students, he served as a summer intern, once for the Congress of the United States and once for the World Bank.[24] In 1991, he graduated with bachelor's degrees in linguistics and diplomacy.[25]

NBA career

Denver Nuggets

In the 1991 NBA draft, the Denver Nuggets drafted Mutombo with the fourth overall pick.[26] The Nuggets ranked last in the NBA in opponent points-per-game and Defensive Rating,[27] and Mutombo's shot-blocking ability made an immediate impression across the league. He developed his signature move in 1992 as a way to become more marketable and gain product endorsement contracts.[28] After blocking a player's shot, he would point his right index finger at that player and move it side to side.[29] That year, Mutombo starred in an Adidas advertisement that used the catchphrase "Man does not fly ... in the house of Mutombo", a reference to his prolific shot-blocking.[30] As a rookie, Mutombo was selected for the All-Star team and averaged 16.6 points, 12.3 rebounds, and nearly three blocks per game.

Mutombo began establishing himself as one of the league's best defensive players, regularly putting up big rebound and block numbers. The 1993–94 season saw Denver continue to improve with Mutombo as the franchise cornerstone. During that season, Mutombo averaged 12.0 points per game, 11.8 rebounds per game, and 4.1 blocks per game.[31] With that, he helped the Nuggets finish with a 42-40 record and qualify as the eighth seed in the playoffs. They were matched up with the top-seeded 63–19 Seattle SuperSonics in the first round.

After falling to an 0-2 deficit in the five-game series, Denver won three straight games to pull off a major playoff upset, becoming the first eighth seed to defeat a number one seed in an NBA playoff series.[32] At the end of Game 5, Mutombo memorably grabbed the game-winning rebound and fell to the ground, holding the ball over his head in a moment of joy.[33] Mutombo's defensive presence was the key to the upset victory; his total of 31 blocks remains a record for a five-game series.[30] In the second round of the playoffs, the Nuggets fell to the Utah Jazz, 4-3.

The following season, he was selected for his second All-Star game and received the NBA Defensive Player of the Year Award. But Denver failed to build on its success from the previous playoffs, as Mutombo lacked a quality supporting cast around him. During his last season with the Nuggets, Mutombo averaged 11.0 points per game, 11.8 rebounds per game and a career-high 4.5 blocks per game.[34]

At the conclusion of the 1995–96 season, Mutombo became a free agent, and reportedly sought a 10-year contract, something the Nuggets considered impossible to offer. Bernie Bickerstaff, then the Nuggets' general manager, later said not bringing back Mutombo was his biggest regret as GM.[35]

Atlanta Hawks

After the 1995–96 NBA season, Mutombo signed a 5-year, $55 million free agent contract with the Atlanta Hawks.[36][37] He and Hawks All-Star Steve Smith led Atlanta to back-to-back 50+-win seasons in 1996–97 (56–26) and 1997–98 (50–32). Mutombo won Defensive Player of the Year both years, continuing to put up excellent defensive numbers with the Hawks. In the 1997 NBA Playoffs, the Hawks defeated the Detroit Pistons in five games. In Game 1 of that series, Mutombo led all scorers and rebounders, with 26 points and 15 rebounds respectively, in a 89-75 win over the Pistons.[38] In the next round, despite Mutombo averaging a double-double and 2.6 blocks per game, the Hawks lost in five games to the defending champion Chicago Bulls.[39] The following season, on April 9, 1998, Mutombo scored 20 points and grabbed 24 rebounds in a 105-102 loss to the Indiana Pacers.[40] That season ended in disappointment for Mutombo and the Hawks, as despite finishing with a similar record to the previous season, Mutombo averaged only 8.0 points and 12.8 rebounds a game while the Hawks lost to their division rival Charlotte Hornets three games to one in the first round.[41] During the lockout-shortened 1998–99 season, he was the NBA's IBM Award winner, a player of the year award determined by a computerized formula. That year, the NBA banned the Mutombo finger wag, and after a period of protest, he complied with the new rule.[42]

In what would be his last full season with the Hawks during the 1999-00 season, Mutombo averaged 11.5 points per game, a career and league-high 14.1 rebounds per game, and 3.3 blocks per game. On December 14, 1999, Mutombo scored 27 points, on 11-for-11 shooting from the field, grabbed a season-high 29 rebounds and recorded a game-high 6 blocks to pull out the win over the Minnesota Timberwolves.[43]

Philadelphia 76ers

At the February 2001 trade deadline, the Hawks traded Mutombo to the Eastern Conference-leading Philadelphia 76ers, along with Roshown McLeod, in exchange for Pepe Sánchez, Toni Kukoč, future teammate Nazr Mohammed, and injured center Theo Ratliff.[44] One week earlier, Mutombo played in the All-Star game; he led the game with 22 rebounds and 3 blocks. Along with game MVP Allen Iverson and coach Larry Brown, both of the 76ers, the East rallied from a 95–74 fourth-quarter deficit to win 111-110 on Mutombo and Iverson's strong performances.[45] After the game, rumors began of a trade sending Mutombo to Philadelphia.[46] With Ratliff out for the remainder of the year, the Sixers needed a big man to compete with potential matchups against Western Conference powers Vlade Divac, Tim Duncan, David Robinson or Shaquille O'Neal, should they reach the NBA Finals.[47]

In arguably his best season as a pro, Mutombo earned his fourth Defensive Player of the Year award that season. During the 2001 Playoffs, they defeated the Indiana Pacers in 4 games, Toronto Raptors in 7 games and Milwaukee Bucks in a 7-game series. During Game 7 against the Bucks, Mutombo scored 23 points, grabbed 19 rebounds and blocked 7 shots to win the series.[48] Mutombo helped the Sixers reach the NBA Finals. After pulling off an upset and winning Game 1 against the Los Angeles Lakers (the only playoff game the Lakers lost in 2001), the Sixers lost the next four games and the series. Matched up against Shaq, Mutombo averaged 16.8 points, 12.2 rebounds and 2.2 blocks. A free-agent, he re-signed with the Sixers after the season to a four-year, $68 million contract.[49]

The 2001–02 season saw a change in the Eastern conference hierarchy; the Sixers were eliminated in the first round of the playoffs, while the New Jersey Nets surged to the top of the standings, making it all the way to the Finals against the Lakers (the Nets were swept).

New Jersey Nets

Looking for a big man to compete with the likes of Shaquille O'Neal and Tim Duncan, the Nets sent future teammate Keith Van Horn and Todd MacCulloch to Philadelphia in exchange for Mutombo.[50] But Mutombo spent most of that season with a nagging injury that limited him to just 24 games. He was generally unable to play in the playoffs, typically serving as a sixth man during the Nets' second consecutive Finals run (they lost to the Spurs in six games). After one contentious season in New Jersey, the Nets bought out the remaining two years on his contract.[51]

New York Knicks

In October 2003, he signed a two-year deal with the New York Knicks.[52] After a dominant performance against the crosstown rival New Jersey Nets that included 10 blocks, Knicks fans began waving their fingers at Mutombo. He chose to respond in kind after a referee told him that as long as the gesture was not directed at a particular player, the league would not punish him.[42] In August 2004, the Knicks traded him to the Chicago Bulls, along with Cezary Trybański, Othella Harrington, and Frank Williams in exchange for Jerome Williams and Jamal Crawford.[53]

Houston Rockets

Prior to the 2004–05 season, the Bulls traded Mutombo to the Houston Rockets for Mike Wilks, Eric Piatkowski and Adrian Griffin.[54] Yao Ming and Mutombo formed one of the NBA's most productive center combos. In his first season with the Rockets, Mutombo averaged 15.2 MPG, 5.3 RPG, 4.0 PPG, and 1.3 BPG. The Rockets lost in the first round to the Dallas Mavericks.

On March 2, 2007, in a win over the Denver Nuggets at age 40, Mutombo became the oldest player in NBA history to record more than 20 rebounds in a game, with 22.[55]

In the 2007–08 season, Mutombo received extensive playing time when Yao went down with a broken bone and averaged double digits in rebounding as a starter. In midst of a 10-game winning streak at the time of Yao's injury, Mutombo stepped in and helped the Rockets win 12 more games to complete a 22-game winning streak, then a team record.[56][57]

On January 10, 2008, in a 102–77 rout of the Los Angeles Lakers, Mutombo recorded 5 blocked shots and surpassed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in total career blocked shots, trailing only Hakeem Olajuwon.[58][59]

After contemplating retirement and spending the first part of 2008 as an unsigned free agent, on December 31, 2008, Mutombo signed with the Houston Rockets for the remainder of the 2008–09 season. He said that the 2009 would be his "farewell tour" and his final season; he was the oldest player in the NBA in 2009.[60] In Game 1 of Houston's first-round playoff series against Portland, Mutombo played for 18 minutes and had nine rebounds, two blocks, and a steal.[61]

In the 2nd quarter of Game 2, Mutombo landed awkwardly and had to be carried from the floor. After the game, he said, "it's over for me for my career" and that surgery would be needed.[60][62] It was later confirmed that the quadriceps tendon of his left knee was ruptured in Game 2.[63] Mutombo announced retirement on April 23, 2009, after 18 seasons in the NBA.[62]

Player profile

The 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) 260 lb (120 kg), Mutombo played center, where he was regarded as one of the top inside defenders of all time. Nicknamed "Mt. Mutombo", his combination of height, power, and long arms led to a record-tying four NBA Defensive Player of the Year awards, a feat equaled only by Ben Wallace. Mutombo was among the top three players in Defensive Player of the Year voting for nine consecutive seasons from 1994 to 2002.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72] Staples of Mutombo's defensive prowess were his outstanding shot-blocking and rebounding power. Over his career, he averaged 2.8 blocks and 10.3 rebounds per game. He is second all-time in registered blocks, behind only Hakeem Olajuwon, and is the 20th most prolific rebounder ever.[73] He was also an eight-time All-Star and was elected into three All-NBA and six All-Defensive Teams.[74] Along with his defensive prowess, Mutombo also contributed offensively, averaging at least 10 points per game until he reached age 35.[74]

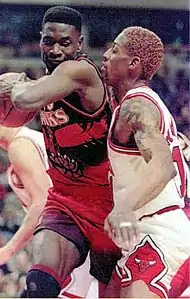

Mutombo also achieved a certain level of on-court notoriety. After a successful block, he was known for taunting his opponents by waving his index finger, like a parent reproaching a disobedient child. Later in his career, NBA officials would respond to the gesture with a technical foul for unsportsmanlike conduct. To avoid the technical foul, Mutombo took to waving his finger at the crowd or the TV cameras after a block, which is not considered taunting by the rules.[75] Additionally, his flailing elbows were known for injuring several NBA players, including Michael Jordan, Dennis Rodman, Charles Oakley, Patrick Ewing, Chauncey Billups, Ray Allen, Yao Ming, LeBron James and Tracy McGrady. His former teammate Yao Ming made a joke about it: "I need to talk to Coach to have Dikembe held out of practice, because if he hits somebody in practice, it's our teammate. At least in the games, it's 50/50."[76]

Personal life

In 1987, Mutombo's 6'10" older brother, Ilo, began playing college basketball in Division II for the Southern Indiana Screaming Eagles as a 26-year-old freshman. The brothers played against each other in a 1990 game at the Capital Centre.[77]

He met his wife, Rose, during a visit to Kinshasa in 1995. They live in Atlanta and have three children together.[78] They also adopted four children from Rose's deceased brothers.[79][80] His son, Ryan, was ranked as the 16th best center in high school and committed in 2021 to play at Georgetown.[81]

Mutombo was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters by the State University of New York College at Cortland in 2004 for his humanitarian work in Africa. More recently, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Georgetown University in 2010. There he delivered the commencement address for Georgetown College of Arts and Sciences, of which he is an alumnus.[82] He also received an honorary doctorate from Haverford College in May 2011.[83]

In November 2015, the NCAA announced Mutombo as a recipient of its Silver Anniversary Awards for 2016. The awards are presented annually to six former NCAA athletes on the 25th anniversary of the final academic year of their college careers, recognizing both excellence of play while in college and professional achievement after college. The announcement cited both his basketball career and extensive humanitarian work.[84]

Mutombo's nephew Harouna Mutombo played college basketball for the Western Carolina Catamounts and professionally in Europe.[85] Harouna was the team's leading scorer for the 2009 season and was named Southern Conference Freshman of the Year.[86] His nephew Haboubacar Mutombo also committed to play basketball at Western Carolina beginning in 2013.[85] His nephew Mfiondu Kabengele played college basketball at Florida State University and was the 2018–19 ACC Sixth Man of the Year.[87] He later was drafted in the first round of the 2019 NBA draft and signed a playing contract with the Los Angeles Clippers.[88]

His son, Ryan Mutombo, currently plays college basketball for Georgetown.[89] Ryan is listed at 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) and plays center. Coming out of high school, Ryan was a highly touted 4 star recruit in the 2021 recruiting class.[90]

Mutombo was among those who witnessed the 2016 Brussels bombings at Brussels Airport on March 22, 2016. Shortly after the bombings, he posted a report on his Facebook page saying that he was safe. His first post said, "God is good. I am in the Brussels Airport with this craziness. I am fine."[91]

On October 15, 2022, he announced that he was undergoing treatment for a brain tumor.[92]

Media

Mutombo made a cameo appearance in the 2002 films Juwanna Mann and Like Mike, which also mentioned his name in its theme song "Basketball".[93][94]

In 2012, Mutombo lent his voice and likeness to a 16-bit style Flash game released by Old Spice humorously titled Dikembe Mutombo's 4 1/2 Weeks to Save the World.[95]

Mutombo appeared in a GEICO auto insurance commercial in February 2013, parodying his shot-blocking ability by applying it to real world situations.[96]

Mutombo co-starred with Kevin Harvick in a Mobil 1 commercial for its annual protection brand, saying "Don't change your oil."[97]

Mutombo had a brief cameo in the 2021 film Coming 2 America as himself.[98]

Humanitarian work

A well-known humanitarian, Mutombo started the Dikembe Mutombo Foundation to improve living conditions in his native Democratic Republic of Congo in 1997. His efforts earned him the NBA's J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award in 2001 and 2009. For his feats, Sporting News named him as one of the "Good Guys in Sports" in 1999 and 2000,[99] and in 1999, he was elected as one of 20 winners of the President's Service Awards, the nation's highest honor for volunteer service.[99] In 2004, he participated in the Basketball Without Borders NBA program, where NBA stars like Shawn Bradley, Malik Rose and DeSagana Diop toured Africa to spread the word about basketball and to improve the infrastructure.[99] He paid for uniforms and expenses for the Zaire women's basketball team during the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta.[99] Mutombo is a spokesman for the international relief agency, CARE and is the first youth emissary for the United Nations Development Program.[80]

Mutombo is a longtime supporter of Special Olympics and is currently a member of the Special Olympics International Board of Directors, as well as a Global Ambassador.[100] He has been a pioneer of Unified Sports, which brings together people with and without intellectual disabilities. He also played in the Unity Cup in South Africa before the 2010 World Cup Quarterfinal, along with South African President Jacob Zuma and Special Olympics athletes from around the world.[101] Mutombo joined his second Unity Cup team in 2012.[102]

In honor of his humanitarianism, Mutombo was invited to President George W. Bush's 2007 State of the Union Address and was referred to as a "son of the Congo" by the President in his speech.[103] Mutombo later said, "My heart was full of joy. I didn't know the President was going to say such great remarks."[104]

On April 13, 2011, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health gave Mutombo the Goodermote Humanitarian Award "for his efforts to reduce polio globally as well as his work improving the health of neglected and underserved populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo."[105] Michael J. Klag, dean of the Bloomberg School of Public Health, said "Mr. Mutombo is a winner in many ways—on the court and as a humanitarian. His work has improved the health of the people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital and Research Center is a model for the region. Likewise, Mr. Mutombo has been instrumental in the fight against polio by bolstering vaccination efforts and bringing treatment to victims of the disease."[105]

In 2012, the Mutombo Foundation, in partnership with Mutombo's alma mater, Georgetown University, began a new initiative that aims to provide care for visually impaired children from low-income families in the Washington, D.C. region. In 2020, the foundation began construction of a modern pre-K through 6th grade school. Named for his father, who died in 2003, it's the Samuel Mutombo Institute of Science & Entrepreneurship, located outside the city of Mbuji-Mayi in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[106][107]

Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital

In 1997, the Mutombo Foundation began plans to open a $29 million, 300-bed hospital on the outskirts of his hometown, the Congolese capital of Kinshasa. Ground was broken in 2001, but construction didn't start until 2004, as Mutombo had trouble getting donations early on although he personally donated $3.5 million toward the hospital's construction.[80] Initially Mutombo had some other difficulties, almost losing the land to the government because it was not being used and having to pay refugees who had begun farming the land to leave. He also struggled to reassure some that he did not have any ulterior or political motives for the project.[80] The project has been on the whole very well received at all social and economic levels in Kinshasa.[80]

On August 14, 2006, Mutombo donated $15 million to the completion of the hospital for its ceremonial opening on September 2, 2006. It was by then named Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital, for his late mother, who died of a stroke in 1997.[108]

When it opened in 2007, the $29 million facility became the first modern medical facility to be built in that area in nearly 40 years.[109] His hospital is on a 12-acre (49,000 m2) site on the outskirts of Kinshasa in Masina, where about a quarter of the city's 7.5 million residents live in poverty. It is minutes from Kinshasa's airport and near a bustling open-air market.

National Constitution Center

Mutombo serves on the Board of Trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, which is a museum dedicated to the U.S. Constitution.[110]

SportsUnited

In 2011, Mutombo also traveled to South Sudan as a SportsUnited sports envoy for the U.S. Department of State. In this capacity, he worked with Sam Perkins to lead a series of basketball clinics and team-building exercises with 50 youth and 36 coaches. This helped contribute to the State Department's mission to remove barriers and create a world in which individuals with disabilities enjoy dignity and full inclusion in society.[111]

Ask The Doctor

In April 2020, Dikembe Mutombo officially joined the team at Ask The Doctor as their chief global officer. Ask The Doctor is a platform that connects people from all over the world to top doctors and healthcare professionals.[112]

Economic development and gender parity

In 2021, he created his eponymous coffee company, initially focused on the Congo, to foster women growers' participation in international commerce.[107]

Career summary and highlights

- 4-time NBA Defensive Player of the Year: 1995, 1997, 1998, 2001

- 8-time NBA All-Star: 1992, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2002

- 3-time All-NBA:

- Second Team: 2001

- Third Team: 1998, 2002

- 6-time All-Defensive:

- First Team: 1997, 1998, 2001

- Second Team: 1995, 1999, 2002

- NBA All-Rookie First Team: 1992

- 2nd in Career NBA Blocks: 3,256

- 2-time NBA regular-season leader, rebounding average: 2000 (14.1), 2001 (13.5)

- 4-time NBA regular-season leader, total rebounds: 1995 (1029), 1997 (929), 1999 (610), 2000 (1157)

- NBA regular-season leader, offensive rebounds: 2001 (307)

- 2-time NBA regular-season leader, defensive rebounds: 1999 (418), 2000 (853)

- 3-time NBA regular-season leader, blocked shots average: 1994 (4.1), 1995 (3.9), 1996 (4.5)

- 5-time NBA regular-season leader, total blocks: 1994 (336), 1995 (321), 1996 (332), 1997 (264), 1998 (277)

- Invited to be a special guest at 2007 President George W. Bush's State of the Union address; commended for his humanitarian aid to his homeland

- Oldest player in NBA history to collect over 20 rebounds in a game (40 years old, March 2, 2007 vs. Denver Nuggets)

- Retired NBA alumnus in Team Africa at the 2015 NBA Africa exhibition game.[113]

- Hall of Fame Class of 2015

- NCAA Silver Anniversary Award (Class of 2016)

- No. 55 retired by the Atlanta Hawks (November 24, 2015)

- No. 55 retired by the Denver Nuggets (October 29, 2016)

- Sager Strong Award (June 25, 2018)

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| * | Led the league |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–92 | Denver | 71 | 71 | 38.3 | .493 | .000 | .642 | 12.3 | 2.2 | .6 | 3.0 | 16.6 |

| 1992–93 | Denver | 82 | 82 | 36.9 | .510 | .000 | .681 | 13.0 | 1.8 | .5 | 3.5 | 13.8 |

| 1993–94 | Denver | 82 | 82 | 34.8 | .569 | .000 | .583 | 11.8 | 1.5 | .7 | 4.1* | 12.0 |

| 1994–95 | Denver | 82 | 82 | 37.8 | .556 | .000 | .654 | 12.5 | 1.4 | .5 | 3.9* | 11.5 |

| 1995–96 | Denver | 74 | 74 | 36.7 | .499 | .000 | .695 | 11.8 | 1.5 | .5 | 4.5* | 11.0 |

| 1996–97 | Atlanta | 80 | 80 | 37.2 | .527 | .000 | .705 | 11.6 | 1.4 | .6 | 3.3 | 13.3 |

| 1997–98 | Atlanta | 82 | 82 | 35.6 | .537 | .000 | .670 | 11.4 | 1.0 | .4 | 3.4 | 13.4 |

| 1998–99 | Atlanta | 50 | 50 | 36.6 | .512 | .000 | .684 | 12.2 | 1.1 | .3 | 2.9 | 10.8 |

| 1999–00 | Atlanta | 82 | 82 | 36.4 | .562 | .000 | .708 | 14.1* | 1.3 | .3 | 3.3 | 11.5 |

| 2000–01 | Atlanta | 49 | 49 | 35.0 | .477 | .000 | .695 | 14.1 | 1.1 | .4 | 2.8 | 9.1 |

| 2000–01 | Philadelphia | 26 | 26 | 33.7 | .495 | .000 | .759 | 12.4* | .8 | .3 | 2.5 | 11.7 |

| 2001–02 | Philadelphia | 80 | 80 | 36.3 | .501 | .000 | .764 | 10.8 | 1.0 | .4 | 2.4 | 11.5 |

| 2002–03 | New Jersey | 24 | 16 | 21.4 | .374 | .000 | .727 | 6.4 | .8 | .2 | 1.5 | 5.8 |

| 2003–04 | New York | 65 | 56 | 23.0 | .478 | .000 | .681 | 6.7 | .4 | .3 | 1.9 | 5.6 |

| 2004–05 | Houston | 80 | 2 | 15.2 | .498 | .000 | .741 | 5.3 | .1 | .2 | 1.3 | 4.0 |

| 2005–06 | Houston | 64 | 23 | 14.9 | .526 | .000 | .758 | 4.8 | .1 | .3 | .9 | 2.6 |

| 2006–07 | Houston | 75 | 33 | 17.2 | .556 | .000 | .690 | 6.5 | .2 | .3 | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| 2007–08 | Houston | 39 | 25 | 15.9 | .538 | .000 | .711 | 5.1 | .1 | .3 | 1.2 | 3.0 |

| 2008–09 | Houston | 9 | 2 | 10.7 | .385 | .000 | .667 | 3.7 | .0 | .0 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| Career | 1196 | 997 | 30.8 | .518 | .000 | .684 | 10.3 | 1.0 | .4 | 2.8 | 9.8 | |

| All-Star | 8 | 3 | 17.5 | .595 | .000 | .750 | 9.3 | .3 | .4 | 1.2 | 6.3 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Denver | 12 | 12 | 42.6 | .463 | .000 | .602 | 12.0 | 1.8 | .7 | 5.8* | 13.3 |

| 1995 | Denver | 3 | 3 | 28.0 | .600 | .000 | .667 | 6.3 | .3 | .0 | 2.3 | 6.0 |

| 1997 | Atlanta | 10 | 10 | 41.5 | .628* | .000 | .719 | 12.3 | 1.3 | .1 | 2.6 | 15.4 |

| 1998 | Atlanta | 4 | 4 | 34.0 | .458 | .000 | .625 | 12.8 | .3 | .3 | 2.3 | 8.0 |

| 1999 | Atlanta | 9 | 9 | 42.2 | .563 | .000 | .702 | 13.9* | 1.2 | .6 | 2.6 | 12.6 |

| 2001 | Philadelphia | 23 | 23 | 42.7 | .490 | .000 | .777 | 13.7 | .7 | .7 | 3.1* | 13.9 |

| 2002 | Philadelphia | 5 | 5 | 34.6 | .452 | .000 | .615 | 10.6 | .6 | .4 | 1.8 | 8.8 |

| 2003 | New Jersey | 10 | 0 | 11.5 | .467 | .000 | 1.000 | 2.7 | .6 | .3 | .9 | 1.8 |

| 2004 | New York | 3 | 0 | 12.7 | .333 | .000 | 1.000 | 3.3 | .0 | .3 | 1.3 | 2.3 |

| 2005 | Houston | 7 | 0 | 14.4 | .545 | .000 | .769 | 5.0 | .3 | .3 | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| 2007 | Houston | 7 | 0 | 5.7 | 1.000 | .000 | 1.000 | 1.6 | .1 | .0 | .4 | 1.3 |

| 2008 | Houston | 6 | 6 | 20.5 | .615 | .000 | .636 | 6.5 | .3 | .2 | 1.8 | 3.8 |

| 2009 | Houston | 2 | 0 | 10.0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | 4.5 | .0 | .5 | 1.0 | .0 |

| Career | 101 | 72 | 30.9 | .517 | .000 | .703 | 9.5 | .8 | .4 | 2.5 | 9.1 | |

See also

- List of National Basketball Association career games played leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career blocks leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff blocks leaders

- List of National Basketball Association annual rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association players with most blocks in a game

References

- "Dikembe Mutombo". NBA Stats. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Dikembe Mutombo Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. basketball-reference.com

- Zillgitt, Jeff (May 22, 2018). "NBA Hall of Famer Dikembe Mutombo wins Sager Strong Award for humanitarian work in Congo". USA Today. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "NBA All-Time Blocks Leaders". ESPN. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Player Game Finder". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Mutombo, Haywood, White among 2015 inductee". NBA. April 6, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- Khan, Brooke (November 5, 2019). Home of the brave : an American history book for kids : 15 immigrants who shaped U.S. history. López de Munáin, Iratxe, 1985-. Emeryville, California. ISBN 978-1-64152-780-4. OCLC 1128884800.

- Robbins, Lix (April 19, 2003). "After a Death, Mutombo Seeks Solace in His Game". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Whitley, Heather (February 16, 2014). "Big hands and a big heart save tiny lives in The Congo". CNN. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Augustyn, Adam (June 21, 2021). "Dikembe Mutombo". Britannica. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- Maske, Mark (January 22, 1991). "Dikembe Mutombo Is a Big Man With Some Big Potential". The Washington Post. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Telander, Rick (November 7, 1994). "World Class". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- Robbins, Liz (December 25, 2002). "Mutombo Works to Build Legacy Off Court". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Mark Maske (January 22, 1991). "Dikembe Mutombo Is a Big Man With Some Big Potential". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Stein, Marc (January 19, 2007). "Mutombo says enough to questioning his age". ESPN.com. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Tam, Eva (November 7, 2013). "Dikembe Mutombo on Life After the NBA". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Vivlamore, Chris (September 10, 2015). "Mutombo's humanitarian efforts greater through basketball". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Moran, Malcolm (March 1, 1990). "Strong Hoya Defense Defeats Connecticut". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Heath, Thomas (April 6, 1995). "Beyond hoop dreams". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Powell, Shuan (September 10, 2015). "Mutombo: Protector of the paint and his homeland". NBA. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Davis, Ken (February 12, 1989). "Georgetown Has an Impenetrable Wall With Mourning, Mutombo". Hartford Courant. Retrieved March 3, 2016 – via Los Angeles Times.

- Wolff, Alexander (March 20, 1989). "Two centers of attention". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Men's Basketball Records - All-Big East Teams". bigeast.org. Archived from the original on November 17, 2002. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Love, Lawrence (November 20, 2009). "Man Cannot Fly in the House of Mutombo". GQ. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Basketball Star Dikembe Mutombo on Sports, Leadership". United States Department of State. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Goldaper, Sam (June 28, 1991). "The Final Word on Draft: Trades". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "1990-91 Denver Nuggets Roster and Stats". Basketball Reference. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Blau, Max (June 4, 2014). "How Dikembe Mutombo's Finger Changed The NBA". BuzzFeed. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Sheridan, Chris (April 30, 2009). "Mutombo's legacy to last beyond hoops". ESPN.com. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Lopez, Aaron (August 13, 2014). "Denver Nuggets A to Z: Dikembe Mutombo". NBA. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Dikembe Mutombo 1993-94 Game Log". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "Eighth-Seeded Nuggets Upset Sonics". NBA. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Schaller, Jake (April 22, 2009). "Mutombo memories". The Gazette. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Dikembe Mutombo 1995-96 Game Log". Basketball-Reference.com.

- Dempsey, Christopher (September 11, 2015). "Bickerstaff: 'Only regret' as Nuggets GM was not re-signing Mutombo". The Denver Post. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Hawks Get Big With Mutombo". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. July 16, 1996. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Shot-blocking Star Mutombo Goes To Hawks". Chicago Tribune. July 16, 1996. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Detroit Pistons at Atlanta Hawks Box Score, April 25, 1997". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- "1997 NBA Eastern Conference Semifinals - Hawks vs. Bulls". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- "Indiana Pacers at Atlanta Hawks Box Score, April 9, 1998". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- "1998 NBA Eastern Conference First Round - Hawks vs. Hornets". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- Pierce, Damien (November 17, 2006). "Mount Mutombo". NBA. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "NBA Report/Mutombo a One-Man Show: 27 Points and 29 Rebounds". Newsday. December 14, 1999. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- Smith, Stephen A. (February 23, 2001). "Sixers Land Mutombo, But Not Without Cost". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "2001 All-Star Game recap". NBA. February 27, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Saladino, Tom (February 21, 2001). "Mutombo mentioned in trade talks". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Mutombo traded to Sixers in six-player deal". ESPN.com. Associated Press. February 23, 2001. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Dikembe Mutombo in 2001: Who Want To Go To L.A. With Me?". The Sports Fan Journal. April 24, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- "76ers trade C Mutombo to Nets". United Press International. August 6, 2002. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Wise, Mike (August 7, 2002). "Nets Get Mutombo From 76ers For Van Horn and MacCulloch". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Popper, Steve; Robbins, Liz (October 5, 2003). "Nets Will Buy Out Mutombo's Contract". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Knicks Make Mutombo Their Center". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 10, 2003. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Guard comes to NY in six-player swap". ESPN.com. August 6, 2004. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Blinebury, Fran (September 7, 2004). "Bulls' Mutombo: Trade to Rockets a done deal". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 3, 2016 – via Chicago Tribune.

- "Elias Says...Mutombo grabs 22 boards, Rockets top Nuggets". ESPN.com. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- Broussard, Chris (March 18, 2013). "Tracy McGrady peeled to Heat's run". ESPN.com. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Pinto, Michael (May 20, 2013). "Unsung Rockets set NBA ablaze with 22-game win streak". NBA. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Duncan, Chris (January 11, 2007). "Mutombo Passes Kareem in Blocks as Rockets Top Lakers". NBA. Associated Press. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Pierce, Damien (January 11, 2007). "Mutombo moves into second on all-time blocks list". NBA. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Knee injury may end Mutombo's career". ESPN.com. Associated Press. April 22, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Rocker 108, Blazers 81 Box Score". ESPN.com. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- McTaggart, Brian (April 22, 2009). "Mutombo suffers career-ending knee injury in Portland". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Mutombo bids farewell after 18 seasons". ESPN.com. Associated Press. April 24, 2009. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "1993-94 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "1994-95 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "1995-96 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "1996-97 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- "1997-98 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- "1998-99 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "1999-00 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "2000-01 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com.

- "2001-02 NBA Awards Voting". Basketball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- "Career Leaders and Records for Total Rebounds". basketball-reference.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Dikembe Mutombo Statistics". basketball-reference.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- Feigen, Jonathan (January 13, 2007). "NBA signs off on Mutombo's finger wave". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "McGrady's OK to play Tuesday vs. Warriors". Houston Chronicle.

- Taylor, Phil (December 3, 1990). "College Basketball". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- "NBA legend: 'We need to go save our mothers, sisters, grandmas'". NBC News. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- Smith, Sam (March 17, 1996). "House Of Mutombo Full Of Kids--and Love". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Nance, Roscoe (August 16, 2006). "Mutombo helps Congo take a big step forward with new hospital". USA Today. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- Krohn, Adam. "Dikembe Mutombo's legacy continues through son". ajc. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- "Dikembe Mutombo to Speak at Georgetown College Commencement – Georgetown University Official Athletic Site". Guhoyas.com. April 28, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Jay NBAFP (April 12, 2011). "Dikembe Mutombo To Be Honored by Haverford College". NBA FrontPage. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- "NCAA honors 2016 Silver Anniversary Award winners" (Press release). NCAA. November 19, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- Kelly, Brad (May 23, 2013). "Pickering's Haboubacar Mutombo commits to Western Carolina". www.durhamregion.com. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- "Player Bio: Harouna Mutombo". catamountsports.com. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Mfiondu Kabengele". Florida State Seminoles. July 19, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- "Clippers sign draft picks Kabengele, Mann". ESPN.com. July 10, 2019.

- "Ryan Mutombo - Men's Basketball - Georgetown University Athletics". GU 2021-2022 Men's Basketball Roster. Georgetown University Athletics. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- "Ryan Mutombo, Lovett School, Center (BK)". 247 Sports. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- "Dikembe Mutombo was at the Brussels Airport attacks, is unharmed". sports.yahoo.com.

- "Mutombo beginning treatment on brain tumor". ESPN.com. October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- Hoffarth, Tom (June 2, 2010). "Let's be reel about this: Celtics beat out the Lakers on the silver screen". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- McNary, Dave (February 11, 2002). "Fox gets NBA stars to like 'Mike'". Variety. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Linn, Tracey (November 26, 2012). "How a team of game developers help Old Spice save the world every five days". Polygon. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Joseph, Adi (February 3, 2013). "Dikembe Mutombo blocks for GEICO in Super Bowl commercial". USA Today. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Mobil 1 Ad Campaign Pairs Kevin Harvick With Dikembe Mutombo". Sports Business Daily. March 10, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- "Coming 2 America full cast listing". IMDb. March 6, 2021.

- "Dikembe Mutombo Info Page". NBA. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Montero, David (July 23, 2015). "Democratic Republic of Congo participates in its first Special Olympics". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Zuma to take the field for Unity Cup". July 2, 2010. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "Mbalula to take to the field". Independent Online. September 3, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "President Bush Delivers State of the Union Address". whitehouse.gov. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- "Dikembe Mutombo stands tall with Bush(video)". AfricaHit.com. January 24, 2007. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- Wood-Wright, Natalie; Health, JH Bloomberg School of Public. "Bloomberg School Awards Goodermote Humanitarian Award to Dikembe Mutombo". Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- "Groundbreaking Ceremony for Samuel Mutombo Institute of Science & Entrepreneurship". Dikembe Mutombo Foundation. August 17, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- Dikembe Mutombo's New Coffee Venture Aims to Make an Impact, Sports Illustrated, Justin Barfrassoa, April 8, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- "Mutombo's hospital dream about to come true". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 10, 2007.

- Rushin, Steve (September 4, 2006). "The Center of Two Worlds". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- "National Constitution Center, Board of Trustees". National Constitution Center Web Site. National Constitution Center. July 26, 2010. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- "Sam Perkins and Dikembe Mutombo Travel to South Sudan | Exchange Programs". exchanges.state.gov. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- "Ask The Doctor Interviews Dikembe Mutombo". Independent Online. December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "NBA's current, former stars put on show in Africa exhibition". ESPN.com. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

External links

- NBA profile

- Dikembe Mutombo Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at Basketball-Reference.com

- "Charting damage by Dikembe" at ESPN

- Dikembe Mutombo Foundation

- Dikembe Mutombo Profile – ClutchFans.net (Houston Rocket Fan Site)

- "On the Shoulders of a Giant", Time, April 20, 2003.