European Union citizenship

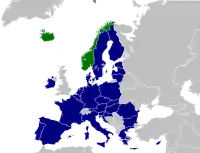

European Union citizenship is afforded to all citizens of member states of the European Union (EU). It was formally created with the adoption of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, at the same time as the creation of the EU. EU citizenship is additional to, as it does not replace, national citizenship.[1][2] It affords EU citizens with rights, freedoms and legal protections available under EU law.

| This article is part of a series on |

Politics of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

EU citizens have freedom of movement, and the freedom of settlement and employment across the EU. They are free to trade and transport goods, services and capital through EU state borders, with no restrictions on capital movements or fees.[3] EU citizens have the right to vote and run as a candidate in certain (often local) elections in the member state where they live that is not their state of origin, while also voting for EU elections and participating in a European Citizens' Initiative (ECI).

Citizenship of the EU confers the right to consular protection by embassies of other EU member states when an individual's country of citizenship is not represented by an embassy or consulate in the foreign country in which they require protection or other types of assistance.[4] EU citizens have the right to address the European Parliament, the European Ombudsman and EU agencies directly, in any of the EU Treaty languages,[5] provided the issue raised is within that institution's competence.[6]

EU citizens have the legal protections of EU law,[7] including the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU[8] and acts and directives regarding protection of personal data, rights of victims of crime, preventing and combating trafficking in human beings, equal pay, as well as protection from discrimination in employment on grounds of religion or belief, sexual orientation and age.[8][9] The office of the European Ombudsman can be directly approached by EU citizens.[10]

History

"The introduction of a European form of citizenship with precisely defined rights and duties was considered as long ago as the 1960s",[11] but the roots of "the key rights of EU citizenship—primarily the right to live and the right to work anywhere within the territory of the Member States—can be traced back to the free movement provisions contained in the Treaty of Paris establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, which entered into force in 1952.[12]" The citizenship of the European Union was first introduced by the Maastricht Treaty, and was extended by the Treaty of Amsterdam.[13] Prior to the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, the European Communities treaties provided guarantees for the free movement of economically active People, but not, generally, for others. The 1951 Treaty of Paris[14] establishing the European Coal and Steel Community established a right to free movement for workers in these industries and the 1957 Treaty of Rome[15] provided for the free movement of workers and services. However, we can find traces of an emerging European personal status in the legal framework regulating the rights and obligations of foreign residents in Europe well before a formal status of European citizenship was introduced. In particular through the interplay between secondary European legislation and the case-law of the European Court of Justice. This formed an embryo of the future European Citizenship,[16] and came to be defined by the practice of freedom of movement of workers within the newly-established European Economic Community.

The rights of an "embryonic"[12] European citizenship have been developed by the European Court of Justice well before the formal institution of European citizenship by the Maastricht Treaty.[17] This could happen after the two landmark decisions in the cases Van Gend en Loos[18] and Costa/ENEL,[19] which established (a) the principle of direct effect of EEC law, and (b) the supremacy of European law over national law, including the constitutional one. In particular, the 1957 Rome Treaty[20] provisions were interpreted by the European Court of Justice not as having a narrow economic purpose, but rather a wider social and economic one.[21]

The rights associated with the European Personal Status were firstly recognized “to certain categories of workers, then expanded to all workers, to certain categories of non-workers (e.g. retirees, students), and finally perhaps to all citizens”.[12] In line with the model of social citizenship proposed by Thomas Humphrey Marshall, the “European Personal Status” or “Proto-European citizenship”[16] was built by recognizing the social rights connected to freedom of movement[20] and freedom of establishment in the first years of the EEC, when workers’ rights in the host state were progressively extended to their family members even beyond the status of "worker",[22][23][24][25][26] so as to promote the full social integration of the workers and their families in the host member state.[27]

When Regulation 1612/68[28] abolished movement and residence restrictions for member state workers and their families in the entire EEC territory, thus ending the transitional period established by article 49 of the Rome Treaty,[29] not only this created the conditions for a full exercise of free movement rights, but a number of important new rights were subsequently recognized by the ECJ, such as: the right to a minimum wage in the host state,[30] the reduction of fares on public transport for large families,[31] the right to a check for disabled adults,[32] interest-free loans for the birth of children,[33] the right to reside with a non-spousal partner,[34] the payment of funeral expenses.[35]

As later stated in Levin,[36] the Court found that the "freedom to take up employment was important, not just as a means towards the creation of a single market for the benefit of the member state economies, but as a right for the worker to raise her or his standard of living".[21] Under the ECJ case-law, the rights of free movement of workers applies regardless of the worker's purpose in taking up employment abroad,[36] to both part-time and full-time work,[36] and whether or not the worker required additional financial assistance from the member state into which he moves.[37]

Before the institution of the European citizenship the ECJ interpreted the status of "worker" it beyond its purely literal meaning, progressively extending it to subjects such as non-economically active family members, students, tourists.[38] This led the Court to hold that a mere recipient of services has free movement rights under the Treaty,[39] so that almost every national of an EU country moving to another member state as a recipient of services, whether economically active or not, but provided they do not constitute an unreasonable burden for the host state, shall non be granted equality of treatment[40] had a right to non-discrimination on the ground of nationality even prior to the Maastricht Treaty.[41]

The Maastrich Treaty dispositions on the status of European citizenship (having direct effect, i.e. directly conferring the status of European citizen to all member states nationals) were not immediately applied by the Court, which continued following the previous interpretative approach and employed European citizenship as a supplementary argument in order to confirm and consolidate precedent law.[42] It was only a few years after the entry into force of the Treaty of Maastricht that the Court finally decided to abandon this approach and to recognize the status of European citizen in order to decide the controversies. Two landmark decisions in this sense are Martinez Sala,[43] and Grelczyk.[44]

On the one hand citizenship has an inclusive character, as it allows its holders freedoms and encourages and enables active participation and active use of these rights. On the other hand, and the following is not meant to diminish this first fact, the inclusion of a certain group results in the differentiation of others. Only through active differentiation and demarcation, i.e. exclusion, an identity with formal criteria can be created.

Due to the history of the EU and its mentioned development, the progress of including and excluding is inevitably full of tensions. Many dynamics in citizenship grounded in the tension between the formal law part and the non-/beyond-law surrounding; such as the enlargement of freedom and rights to every kind of explicitly or implicitly economically active persons. Homeless and poor people do not enjoy these freedoms, because of a lack of economic action. The situation is the same when the home state says someone might no longer enjoy these rights.

Economically inactive EU citizens who want to stay longer than three months in another Member State have to fulfill the condition of having health insurance and “sufficient resources” in order not to become an “unreasonable burden” for the social assistance system of the host Member State, which otherwise can legitimately expel them.[45]

Stated rights

The rights of EU Citizens are enumerated in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the Charter of Fundamental Rights.[47] Historically, the main benefit of being a citizen of an EU state has been that of free movement. The free movement also applies to the citizens of European Economic Area countries[48] and Switzerland.[49] However, with the creation of EU citizenship, certain political rights came into being.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

The adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) enshrined specific political, social, and economic rights for EU citizens and residents. Title Five of the CFR focuses specifically on the rights of EU Citizens. Protected rights of EU citizens include the following:[50]

- The right to vote and to stand as a candidate at elections to the European Parliament.

- The right to vote and to stand as a candidate at municipal elections.

- The right to good administration.

- The right of access to documents.

- The right to petition.

- Freedom of movement and of residence.

- Diplomatic and consular protection.

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[51] provides for citizens to be "directly represented at Union level in the European Parliament" and "to participate in the democratic life of the Union" (Treaty on the European Union, Title II, Article 10). Specifically, the following rights are afforded:[1]

- Accessing European government documents: a right to access to documents of the EU government, whatever their medium. (Article 15).

- Freedom from any discrimination on nationality: a right not to be discriminated against on grounds of nationality within the scope of application of the Treaty (Article 18);

- Right to not be discriminated against: The EU government may take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation (Article 19);

- Right to free movement and residence: a right of free movement and residence throughout the Union and the right to work in any position (including national civil services with the exception of those posts in the public sector that involve the exercise of powers conferred by public law and the safeguard of general interests of the State or local authorities (Article 21) for which however there is no one single definition);

- Voting in European elections: a right to vote and stand in elections to the European Parliament, in any EU member state (Article 22)

- Voting and running in municipal elections: a right to vote and stand in local elections in an EU state other than their own, under the same conditions as the nationals of that state (Article 22)

- Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23)

- This is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (some countries have only one embassy from an EU state).[52]

- Petitioning Parliament and the Ombudsman: the right to petition the European Parliament and the right to apply to the European Ombudsman to bring to his attention any cases of poor administration by the EU institutions and bodies, with the exception of the legal bodies (Article 24)[53]

- Language rights: the right to apply to the EU institutions in one of the official languages and to receive a reply in that same language (Article 24)

Free movement rights

- Article 21 Freedom to move and reside

Article 21 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[51] states that

Every citizen of the Union shall have the right to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States, subject to the limitations and conditions laid down in this Treaty and by the measures adopted to give it effect.

The European Court of Justice has remarked that,

EU Citizenship is destined to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States[54]

The ECJ has held that this Article confers a directly effective right upon citizens to reside in another Member State.[54][55] Before the case of Baumbast,[55] it was widely assumed that non-economically active citizens had no rights to residence deriving directly from the EU Treaty, only from directives created under the Treaty. In Baumbast, however, the ECJ held that (the then)[56] Article 18 of the EC Treaty granted a generally applicable right to residency, which is limited by secondary legislation, but only where that secondary legislation is proportionate.[57] Member States can distinguish between nationals and Union citizens but only if the provisions satisfy the test of proportionality.[58] Migrant EU citizens have a "legitimate expectation of a limited degree of financial solidarity... having regard to their degree of integration into the host society"[59] Length of time is a particularly important factor when considering the degree of integration.

The ECJ's case law on citizenship has been criticised for subjecting an increasing number of national rules to the proportionality assessment.[58]

- Article 45 Freedom of movement to work

Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[51] states that

- Freedom of movement for workers shall be secured within the Union.

- Such freedom of movement shall entail the abolition of any discrimination based on nationality between workers of the Member States as regards employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment.

State employment reserved exclusively for nationals varies between member states. For example, training as a barrister in Britain and Ireland is not reserved for nationals, while the corresponding French course qualifies one as a 'juge' and hence can only be taken by French citizens. However, it is broadly limited to those roles that exercise a significant degree of public authority, such as judges, police, the military, diplomats, senior civil servants or politicians. Note that not all Member States choose to restrict all of these posts to nationals.

Much of the existing secondary legislation and case law was consolidated[60] in the Citizens' Rights Directive 2004/38/EC on the right to move and reside freely within the EU.[61]

- Limitations

New member states may undergo transitional regimes for Freedom of movement for workers, during which their nationals only enjoy restricted access to labour markets in other member states. EU member states are permitted to keep restrictions on citizens of the newly acceded countries for a maximum of seven years after accession. For the EFTA states (Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway and Switzerland), the maximum is nine years.

Following the 2004 enlargement, three "old" member states—Ireland, Sweden and the United Kingdom—decided to allow unrestricted access to their labour markets. By December 2009, all but two member states—Austria and Germany—had completely dropped controls. These restrictions too expired on 1 May 2011.[62]

Following the 2007 enlargement, all pre-2004 member states except Finland and Sweden imposed restrictions on Bulgarian and Romanian citizens, as did two member states that joined in 2004: Malta and Hungary. As of November 2012, all but 8 EU countries have dropped restrictions entirely. These restrictions too expired on 1 January 2014. Norway opened its labour market in June 2012, while Switzerland kept restrictions in place until 2016.[62]

Following the 2013 enlargement, some countries implemented restrictions on Croatian nationals following the country's EU accession on 1 July 2013. As of March 2021, all EU countries have dropped restrictions entirely.[63][64]

Acquisition

There is no common EU policy on the acquisition of European citizenship as it is supplementary to national citizenship. (EC citizenship was initially granted to all citizens of European Community member states in 1994 by the Maastricht treaty concluded between the member states of the European community under international law, this changed into citizenship of the European Union in 2007 when the European Community changed its legal identity to be the European Union. Many more people became EU citizens when each new EU member state was added and, at each point, all the existing member states ratified the adjustments to the treaties to allow the creation of those extra citizenship rights for the individual. European citizenship is also generally granted at the same time as national citizenship is granted). Article 20 (1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[51] states that:

"Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Citizenship of the Union shall be additional to and not replace national citizenship."

While nationals of Member States are citizens of the union, "It is for each Member State, having due regard to Union law, to lay down the conditions for the acquisition and loss of nationality."[65] As a result, there is a great variety in rules and practices with regard to the acquisition and loss of citizenship in EU member states.[66]

Exceptions for overseas territories

In practice this means that a member state may withhold EU citizenship from certain groups of citizens, most commonly in overseas territories of member states outside the EU.

A previous example, was for the United Kingdom. Owing to the complexity of British nationality law, a 1982 declaration by Her Majesty's Government defined who would be deemed to be a British "national" for European Union purposes:[67]

- British citizens, as defined by Part I of the British Nationality Act 1981.

- British subjects, within the meaning of Part IV of the British Nationality Act 1981, but only if they also possessed the 'right of abode' under British immigration law.

- British overseas territories citizens who derived their citizenship by a connection to Gibraltar.

This declaration therefore excluded from EU citizenship various historic categories of British citizenship generally associated with former British colonies, such as British Overseas Citizens, British Nationals (Overseas), British protected persons and any British subject who did not have the 'right of abode' under British immigration law.

In 2002, with the passing of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002, EU citizenship was extended to almost all British overseas territories citizens when they were automatically granted full British citizenship (with the exception of those with an association to the British sovereign base areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia on the Island of Cyprus).[68] This had effectively granted them full EU citizenship rights, including free movement rights, although only residents of Gibraltar had the right to vote in European Parliament elections. In contrast, British citizens in the Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man had always been considered to be EU citizens but, unlike residents of the British overseas territories, were prohibited from exercising EU free movement rights under the terms of the British Accession Treaty if they had no other connection with the UK (e.g. they had lived in the UK for five years, were born in the UK, or had parents or grandparents born in the UK) and had no EU voting rights. (see Guernsey passport, Isle of Man passport, Jersey passport).[69]

Another example are the residents of Faroe Islands of Denmark who, though in possession of full Danish citizenship, are outside the EU and are explicitly excluded from EU citizenship under the terms of the Danish Accession Treaty.[70] This is in contrast to residents of the Danish territory of Greenland who, whilst also outside the EU as a result of the 1984 Greenland Treaty, do receive EU citizenship as this was not specifically excluded by the terms of that treaty (see Faroe Islands and the European Union; Greenland and the European Union).

Greenland

Although Greenland withdrew from the European Communities in 1985, the autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark remains associated with the European Union, being one of the overseas countries and territories of the EU. The relationship with the EU means that all Danish citizens residing in Greenland are EU citizens. This allows Greenlanders to move and reside freely within the EU. This contrasts with Danish citizens living in the Faroe Islands who are excluded from EU citizenship.[71]

Summary of member states' nationality laws

This is a summary of nationality laws for each of the twenty-seven EU member states.[72]

| Member State | Acquisition by birth | Acquisition by descent | Acquisition by marriage or civil partnership | Acquisition by naturalisation | Multiple nationality permitted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

People born in Austria:

|

Austrian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Only allowed with special permission or if dual citizenship was obtained at birth (binational parents [one Austrian, one foreign] or birth in a jus-soli country such as USA and Canada) | ||

|

People born in Belgium who:

|

Belgian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Bulgaria who:

|

Bulgarian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

| ||

People born in Croatia who:

|

Croatian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:[74][75][76]

Conditions

|

|

|

| ||

|

People born in Cyprus who:

|

Cypriot nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in the Czech Republic:

|

|

|

|

Yes, effective 1 January 2014[77] | ||

|

People born in Denmark who:

|

|

|

|

Yes, effective 1 September 2015[78] | ||

|

People born in Estonia who:

|

|

No (unless married to an Estonian citizen before 26 February 1992) |

|

Estonia does not recognise multiple citizenship. However, Estonian citizens by descent cannot be deprived of their Estonian citizenship, and are de facto allowed to have multiple citizenship. | ||

|

People born in Finland who:

(Possibility to obtain citizenship by declaration exists for inborn aliens who have lived a major part of their childhood in Finland.) |

Finnish nationality is acquired by descent from a Finnish mother, and from a Finnish father under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

At birth, People born in France who:

|

French nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

Naturalisation conditions

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Germany, if at least one parent has resided in Germany for at least 8 years and holds a permanent residence permit |

German nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

No, unless: Conditions

| ||

|

People born in Greece who:

|

Greek nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Hungary who:

|

Hungarian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Ireland:

|

Irish nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Italy who:

|

Italian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Latvia who: |

Latvian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: |

No |

|

Starting from 1 October 2013 hereby listed People are eligible[88] to have dual citizenship with Latvia:

| ||

|

People born in Lithuania who:

|

Lithuanian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

No, unless:

Conditions

| ||

|

People born in Luxembourg who:

|

|

|

Yes | |||

|

Maltese nationality is acquired by descent under the following condition:

|

|

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Netherlands who:

|

Dutch nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

After 5 years uninterrupted residence, with continuous registration in the municipal register |

Conditions

People over 18 with multiple nationalities must live in the Kingdom of the Netherlands or the EU for at least one year out of every thirteen years, or receive a Dutch passport or a nationality certificate once every thirteen years. | ||

|

Polish nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

Descendants of Polish-language/ethnic People in some neighbouring countries including Belarus, Lithuania, Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine et al., can apply for Karta Polaka which gives many of the same rights as Polish citizenship but serves as a substitute when acquisition of Polish citizenship would result in the loss of the person's earlier citizenship. |

|

|

Yes but in Poland, Polish identification must be used and the dual citizen is treated legally as only Polish | ||

|

A person who is not descended from a Portuguese citizen becomes a Portuguese citizen at the moment of birth, by the effect of the law itself, if that person was born in Portugal and:

A person who is not descended from a Portuguese citizen and who is not covered by the conditions for automatic attribution of nationality by birth in Portugal set out above, has a right to declare that he or she wants to become a Portuguese citizen, and that person becomes a natural-born Portuguese citizen, with effects retroactive to the moment of birth, upon the registration of such declaration in the Portuguese Civil Registry (by application made by that person, once of age, or by a legal representative of that person, during minority), if that person was born in Portugal and:

|

Portuguese nationality is transmitted by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

Naturalisation conditions

|

Yes | ||

|

People born in Romania who:

|

Romanian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Yes[92] | ||

|

People born in Slovakia:

|

Slovak nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: |

|

|

Dual citizenship is only permitted to Slovak citizens who acquire a second citizenship by birth or through marriage; and to foreign nationals who apply for Slovak citizenship and meet the requirements of the Citizenship Act.[93][94] | ||

|

A child born in Slovenia is a Slovenian citizen if either parent is a Slovenian citizen. Where the child is born outside Slovenia the child will be automatically Slovenian if:

A person born outside Slovenia with one Slovenian parent who is not Slovenian automatically may acquire Slovenian citizenship through:

Children adopted by Slovenian citizens may be granted Slovenian citizenship. |

Slovenian nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions:

|

|

|

| ||

|

People born in Spain who:

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

People born in Sweden who:

|

Swedish nationality is acquired by descent under one of the following conditions: Conditions

|

|

|

Yes | ||

Loss of EU citizenship due to member state withdrawal

The general rule for losing EU citizenship is that European citizenship is lost if member state nationality is lost,[98] but the automatic loss of EU citizenship as a result of a member state withdrawing from the EU is the subject of debate.[99]

One school of legal thought indicates that the Maastricht treaty created the European Union as a legal entity, it then also created the status of EU citizen which gave an individual relationship between the EU and its citizens, and a status of EU citizen. Clemens Rieder suggests a case can be made that "[n]one of the Member States were forced to confer the status of EU citizenship on their citizens but once they have, according to this argument, they cannot simply withdraw this status.". In this situation, no EU citizen would involuntarily lose their citizenship due to their nation's withdrawal from the EU.[99]

It is likely that only a court case before the European Court of Justice would be able to properly determine the correct legal position in this regard, as there is no definitive legal certainty in this area. As of 7 February 2018, the District Court of Amsterdam decided to refer the matter to the European Court of Justice,[100] but the state of the Netherlands has appealed against this referral decision.[101]

United Kingdom

As a result of the Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the opinion of both the European Union and the British government has been that British citizens would lose their EU citizenship and EU citizens would lose their automatic right to stay in the UK. To account for the problems arising from this, a provisional agreement outlines the right of British citizens to remain in the EU (and vice versa) where they are resident in the Union on the day of the UK's withdrawal.[102][103] EU citizens may remain in the UK post-Brexit if and only if they apply to EU Settlement Scheme. The only exception to this is Irish citizens, who are entitled to live and work in the United Kingdom under the Common Travel Area.

European Citizens' Initiatives to challenge Brexit

As a result of the Brexit referendum, there were three European Citizens' Initiatives that were registered which sought to protect the rights and/or status of British EU citizens.[104][105][106] Out of these three initiatives, the one with the strongest legal argument was registered on 27 March 2017 and officially named "EU Citizenship for Europeans: United in Diversity in Spite of jus soli and jus sanguinis". It is clear that the initiative abides by the first school of thought mentioned above because the annexe that was submitted with the initiative clearly makes reference to Rieder's work.[105] In an article titled "Extending [full] EU citizenship to UK nationals ESPECIALLY after Brexit" and published with the online magazine Politics Means Politics, the creator of the initiative argues that British nationals must keep their EU citizenship by detaching citizenship of the European Union from Member State nationality. Perhaps the most convincing and authoritative source that is cited in the article is the acting President of the European Court of Justice, Koen Lenaerts who published an article where he explains how the Court analyses and decides cases dealing with citizenship of the European Union.[107] Both Lenaerts and the creator of the Initiative refer to rulings by the European Court of Justice which state that:

- “Citizenship of the Union is intended to be the fundamental status of nationals of the Member States” (inter alia: Grzelczyk, paragraph 31; Baumbast and R, paragraph 82; Garcia Avello, paragraph 22; Zhu and Chen, parag. 25; Rottmann, parag. 43; Zambrano, parag. 41, etc.)

- "Article 20 TFEU precludes national measures that have the effect of depriving citizens of the Union of the genuine enjoyment of the substance of the rights conferred by virtue of their status as citizens of the Union" (Inter alia: Rottmann, parag. 42; Zambrano, parag. 42; McCarthy, parag 47; Dereci, parag. 66; O and Others, parag. 45; CS, parag. 26; Chavez-Vilchez and Others, parag. 61, etc.)

Based on the argument presented by "EU Citizenship for Europeans" and its creator, Brexit is a textbook definition of a Member State depriving a European citizen of his or her rights as EU citizens, and therefore a legal act is necessary to protect not just rights but the status of EU citizen itself. Despite variances in interpretation of some points of law raised by the Initiative, the European Commission's decision to register the initiative confirms the strength and merit of the initiative's legal argument. On the other hand, the counter-argument is that citizenship of the Union is expressly conferred only upon nationals of Member States, and has been lost by UK nationals because the UK has ceased to be a Member State.

Associate Citizenship

A proposal made first by Guy Verhofstadt, the European Parliament's Brexit negotiator, to help cover the rights of British citizens post-Brexit would see British citizens able to opt-out of the loss of EU citizenship as a result of the general clauses of the withdrawal agreement. This would allow visa-free working on the basis of their continuing rights as EU citizens. This, he termed, "associate citizenship". This has been discussed with the UK's negotiator David Davis.[108][109] However, it was made clear by the British government that there would be no role for EU institutions concerning its citizens, effectively removing the proposal as a possibility.[110]

Danish opt-out

Denmark obtained four opt-outs from the Maastricht Treaty following the treaty's initial rejection in a 1992 referendum. The opt-outs are outlined in the Edinburgh Agreement and concern the EMU (as above), the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) and the citizenship of the European Union. The citizenship opt-out stated that European citizenship did not replace national citizenship; this opt-out was rendered meaningless when the Amsterdam Treaty adopted the same wording for all members. The policy of recent Danish governments has been to hold referendums to abolish these opt-outs, including formally abolishing the citizenship opt-out which is still legally active even if redundant.

Availability to people with European ancestry

Given the substantial number of Europeans who emigrated throughout the world in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the extension of citizenship by descent, or jus sanguinis, by some EU member states to an unlimited number of generations of those emigrants' descendants, there are potentially many tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of people currently outside Europe who have a claim to citizenship in an EU member state and, by extension, to EU citizenship.[111][112] There have also been extensive debates in European national legislatures on whether, and to what extent, to modify nationality laws of a number of countries to further extend citizenship to these groups of ethnic descendants, potentially dramatically increasing the pool of EU citizens further.[112]

If these individuals were to overcome the bureaucratic hurdles of certifying their citizenship, they would enjoy freedom of movement to live anywhere in the EU, under the 1992 European Court of Justice decision Micheletti v Cantabria.[111][113][112]

See also

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union

- European citizens' consultations

- European Citizens' Initiative

- Europe for Citizens

- Four Freedoms (European Union)

- National identity cards in the European Economic Area

- Naturalisation

- Passport of the European Union

- Visa requirements for the European Union citizens

References

- "EUR-Lex - 12012E/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Residence rights when living abroad in the EU". Your Europe - Citizens.

- "The Four Freedoms". Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- "Official Journal C 326/2012". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- "Uprawnienia wynikające z obywatelstwa UE". ue.wyklady.org. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- "What does Brexit mean for equality and human rights in the UK? – Equality and Human Rights Commission". equalityhumanrights.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "European Commission, official website". European Commission - European Commission.

- "Co nam daje obywatelstwo Unii Europejskiej – czyli korzyści płynące z obywatelstwa UE". lci.org.pl. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "The citizens of the Union and their rights | Fact Sheets on the European Union | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Maas, Willem (1 August 2014). "The Origins, Evolution, and Political Objectives of EU Citizenship". German Law Journal. 15 (5): 800. doi:10.1017/S2071832200019155. ISSN 2071-8322. S2CID 150554871.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Denmark. "The Danish Opt-Outs". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Article 69.

- Title 3.

- Menéndez, Agustín José. (2020). Challenging European Citizenship : Ideas and Realities in Contrast. Espen D. H. Olsen. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-030-22281-9. OCLC 1111975337.

- Olsen, Espen D.H. (2008). "The origins of European citizenship in the first two decades of European integration". Journal of European Public Policy. 15 (1): 53. doi:10.1080/13501760701702157. ISSN 1350-1763. S2CID 145481600.

- "EUR-Lex - 61962CJ0026 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- "EUR-Lex - 61964CJ0006 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- art 48. "EUR-Lex - 11957E/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu (in German, French, Italian, and Dutch). Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- Craig, P.; de Búrca, G. (2003). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (3rd ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 706–711. ISBN 978-0-19-925608-2.

- "Guerra C-6/67". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Merola C-45/72". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Scutari C-76/72". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Frilli C-1/72". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Castelli C-261/83". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Mutsch C-137/84". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 of the Council of 15 October 1968 on freedom of movement for workers within the Community, 19 October 1968, retrieved 31 May 2022

- Pioneers of European integration : citizenship and mobility in the EU. Ettore Recchi, Adrian Favell. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. 2009. ISBN 978-1-84844-659-5. OCLC 416294178.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Hoekstra C-75/63". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Cristini C-32/75". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Inzirillo C-63/76". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Reina C-65/81". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Reed C-59/85". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "O'Flynn C-237/94". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Case 53/81 D.M. Levin v Staatssecretaris van Justitie.

- Case 139/85 R. H. Kempf v Staatssecretaris van Justitie.

- Cowan C-186/87.

- Joined cases 286/82 and 26/83 Graziana Luisi and Giuseppe Carbone v Ministero del Tesoro.

- Case 186/87 Ian William Cowan v Trésor public.

- Advocate General Jacobs' Opinion in Case C-274/96 Criminal proceedings against Horst Otto Bickel and Ulrich Franz at paragraph [19].

- Kostakopoulou, Dora (2008). "The Evolution of European Union Citizenship". European Political Science. 7 (3): 285–295. doi:10.1057/eps.2008.24. ISSN 1680-4333. S2CID 145214452.

- Case C-85/96 María Martínez Sala v Freistaat Bayern.

- "Grelczyk C-184/99". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- Heindlmaier, Anita (20 March 2020). "Mobile EU Citizens and the "Unreasonable Burden": How EU Member States Deal with Residence Rights at the Street Level". EU Citizenship and Free Movement Rights: 129–154. doi:10.1163/9789004411784_008. ISBN 9789004411784. S2CID 216237572.

- "Croatian Passport the 'Blue' Sheep of the 'Burgundy' EU Family". CroatiaWeek. 15 February 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- STAS, Magali (31 January 2019). "EU citizenship". European Union. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "EEA Agreement". European Free Trade Association. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "Switzerland". European Commission. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- "EUR-Lex - 12012P/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)

- Central African Republic (France, EU delegation), Comoros (France), Lesotho (Ireland, EU delegation), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Timor-Leste (Portugal, EU delegation), Vanuatu (France, EU delegation)

- This right also extends to "any natural or legal person residing or having its registered office in a Member State": Treaty of Rome (consolidated version), Article 194.

- Case C-184/99 Rudy Grzelczyk v Centre public d'aide sociale d'Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve .

- Case C-413/99 Baumbast and R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, para. [85]-[91].

- Now article 20

- Durham European Law Institute, European Law Lecture 2005 Archived 22 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, p. 5.

- Arnull, Anthony; Dashwood, Alan; Dougan, Michael; Ross, Malcolm; Spaventa, Eleanor; Wyatt, Derrick (2006). European Union Law (5th ed.). Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 978-0-421-92560-1.

- Dougan, M. (2006). "The constitutional dimension to the case law on Union citizenship". European Law Review. 31 (5): 613–641.. See also Case C-209/03 R (Dany Bidar) v. London Borough of Ealing and Secretary of State for Education and Skills, para. [56]-[59].

- European Commission. "Right of Union citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States". Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States.

- "Free movement of labour in the EU 27". Euractiv. 25 November 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- "Work permits". Your Europe – Citizens.

- "Austria to Extend Restrictions for Croatian Workers until 2020". Total Croatia News. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Case C-396/90 Micheletti v. Delegación del Gobierno en Cantabria, which established that dual-nationals of a Member State and a non-Member State were entitled to freedom of movement; case C-192/99 R v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex p. Manjit Kaur. It is not an abuse of process to acquire nationality in a Member State solely to take advantage of free movement rights in other Member States: case C-200/02 Kunqian Catherine Zhu and Man Lavette Chen v Secretary of State for the Home Department.

- Dronkers, J. and M. Vink (2012). Explaining Access to Citizenship in Europe: How Policies Affect Naturalisation Rates. European Union Politics 13(3) 390–412; Vink, M. and G.R. de Groot (2010). Citizenship Attribution in Western Europe: International Framework and Domestic Trends. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(5) 713–734.

- Wikisource: Declaration by the UK on 31 December 1982 on the definition of the term "nationals"

- British Overseas Territories Act 2002, s.3(2)

- "Protocol 3 to the 1972 Accession Treaty".

- "Protocol 2 to the 1972 Accession Treaty".

- Article 4 of the Faroe Islands Protocol, 355(5)(a) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article of the Treaty on European Union (as amended).

- See the EUDO Citizenship Observatory for a comprehensive database with information on regulations on the acquisition and loss of citizenship across Europe.

- "Lex.bg – Закони, правилници, конституция, кодекси, държавен вестник, правилници по прилагане". lex.bg.

- magicmarinac.hr. "Zakon o hrvatskom državljanstvu". Zakon.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

Articles I–X

- "Croatian citizenship" (PDF). eudo-citizenship.eu. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

Articles I–X

- "Croatian citizenship". template.gov.hr. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "New Citizenship legislation of the Czech Republic". www.mzv.cz.

- "Dobbelt statsborgerskab". justitsministeriet.dk. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Citizenship Act". riigiteataja.ee.

- "Nationalité française : enfant né en France de parents étrangers". Government of France. 16 March 2017.

- "Nationality - Consulat général de France à New York". Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "Nationalité française par mariage | service-public.fr". www.service-public.fr.

- "Nationality Act". www.gesetze-im-internet.de. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "How to Get German Citizenship?". Germany Visa. 16 July 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "Becoming a German citizen by naturalization". Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "Becoming a German citizen by naturalization". Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- "Criteria underlying legislation concerning citizenship". Ministero Dell'Interno. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- DELFI (26 May 2013). "Двойное гражданство: у посольств Латвии прибавится работы". DELFI.

- "Acquiring Latvian citizenship". pmlp.gov.lv.

- Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en (14 December 2011). "Losing Dutch nationality". government.nl. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- Naturalisatiedienst, Immigratie- en. "Renouncing your current nationality". ind.nl. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Slovak Citizenship Requirements & Application". Slovak-Republic.org. n.d. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Futej & Partners, Memorandum: Extensive amendment to the act on Slovak state citizenship (PDF), Bratislava

- "Inicio".

- Law (2001:82) on Swedish citizenship

- "Krav för medborgarskap för dig som är nordisk medborgare" (in Swedish). Migrationsverket. 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- "GUIDELINES INVOLUNTARY LOSS OF EUROPEAN CITIZENSHIP (ILEC Guidelines 2015)" (PDF).

- Clemens M. Rieder (2013). "The Withdrawal Clause of the Lisbon Treaty in the Light of EU Citizenship (Between Disintegration and Integration)". Fordham International Law Journal. 37 (1).

- "ECJ asked to rule on Britons' EU citizenship".

- "Appeal allowed against post-Brexit EU citizenship bid". 5 March 2018.

- EU citizens' rights and Brexit, European Commission

- Main points of agreement between UK and EU in Brexit deal, the guardian 8 December 2017

- "European Free Movement Instrument – Initiative details – European Citizens' Initiative". European Commission. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "EU Citizenship for Europeans: United in Diversity in Spite of jus soli and jus sanguinis – Initiative details – European Citizens' Initiative". European Commission. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Retaining European Citizenship – Initiative details – European Citizens' Initiative". European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Lenaerts, Koen (19 October 2015). "EU citizenship and the European Court of Justice's 'stone-by-stone' approach". International Comparative Jurisprudence. doi:10.1016/j.icj.2015.10.005.

- "Brits should not lose EU citizenship rights after Brexit, leaked European Parliament plan says". Independent.co.uk. 29 March 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "U.K. Open to Talking About Associate Citizenship After Brexit". Bloomberg L.P. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "ECJ will have no future role in interpreting UK law post Brexit: UK..." Reuters. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Mateos, Pablo. "External and Multiple Citizenship in the European Union. Are 'Extrazenship' Practices Challenging Migrant Integration Policies?". Princeton University. pp. 20–23. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Joppke, Christian (2003). "Citizenship between De- and Re- Ethnicization". European Journal of Sociology. 44 (3): 429–458. doi:10.1017/S0003975603001346. JSTOR 23999548. S2CID 232174590.

- Moritz, Michael D. (2015). "The Value of Your Ancestors: Gaining 'Back-Door' Access to the European Union Through Birthright Citizenship". Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law. 26: 239–240.

Further reading

- Alvarado, Ed (2016). Citizenship vs Nationality: drawing the fundamental border with law and etymology. Master's thesis at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna.

- Maas, Willem (2007). Creating European Citizens. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5485-6.

- Meehan, Elizabeth (1993). Citizenship and the European Community. London: Sage. ISBN 978-0-8039-8429-5.

- O'Leary, Síofra (1996). The Evolving Concept of Community Citizenshippublisher=Kluwer Law International. The Hague. ISBN 978-90-411-0878-4.

- Soysal, Yasemin (1994). Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. University of Chicago Press.

- Wiener, Antje (1998). 'European' Citizenship Practice: Building Institutions of a Non-State. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3689-3.

- European Commission. "Right of Union citizens and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States".

External links

- EU Citizenship, European Commission Directorate-General for Justice

- EUDO Citizenship Observatory