Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands (Marshallese: Ṃajeḷ),[9] officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands (Marshallese: Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),[note 1] is an independent island country near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the International Date Line. Geographically, the country is part of the larger island group of Micronesia. The country's population of 58,413 people (at the 2018 World Bank Census[10]) is spread out over five islands and 29 coral atolls,[2] comprising 1,156 individual islands and islets. The capital and largest city is Majuro. It has the largest portion of its territory composed of water of any sovereign state, at 97.87%. The islands share maritime boundaries with Wake Island to the north,[note 2] Kiribati to the southeast, Nauru to the south, and Federated States of Micronesia to the west. About 52.3% of Marshall Islanders (27,797 at the 2011 Census) live on Majuro.[2] In 2016, 73.3% of the population were defined as being "urban". The UN also indicates a population density of 760 inhabitants per square mile (295/km2), and its projected 2020 population is 59,190.[11]

Republic of the Marshall Islands Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ (Marshallese) | |

|---|---|

Flag

Seal

| |

| Motto: "Jepilpilin ke ejukaan" "Accomplishment through joint effort" | |

| Anthem: "Forever Marshall Islands" | |

_(Polynesia_centered).svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | Delap-Uliga-Djarrit on Majuro[1] 7°7′N 171°4′E |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups (2006[2]) |

|

| Religion (2020) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Marshallese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic with an executive presidency |

• President | David Kabua |

• Speaker | Kenneth Kedi[4] |

| Legislature | Nitijela |

| Independence from the United States | |

• Self-government | May 1, 1979 |

• Compact of Free Association | October 21, 1986 |

| Area | |

• Total | 181.43 km2 (70.05 sq mi) (189th) |

• Water (%) | n/a (negligible) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 61,988[5] (187th) |

• 2011 census | 53,158[6] |

• Density | 293.0/km2 (758.9/sq mi) (28th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $215 million |

• Per capita | $3,789[7] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $220 million |

• Per capita | $3,866[7] |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 131st |

| Currency | United States dollar (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (MHT) |

| Date format | MM/DD/YYYY |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +692 |

| ISO 3166 code | MH |

| Internet TLD | .mh |

| |

Micronesian settlers reached the Marshall Islands using canoes circa 2nd millennium BC, with interisland navigation made possible using traditional stick charts. They eventually settled there.[12] Islands in the archipelago were first explored by Europeans in the 1520s, starting with Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer in the service of Spain, Juan Sebastián Elcano and Miguel de Saavedra. Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar reported sighting an atoll in August 1526.[12] Other expeditions by Spanish and English ships followed. The islands derive their name from John Marshall, who visited in 1788. The islands were historically known by the inhabitants as "jolet jen Anij" (Gifts from God).[13] Spain claimed the islands in 1592, and the European powers recognized its sovereignty over the islands in 1874. They had been part of the Spanish East Indies formally since 1528. Later, Spain sold some of the islands to the German Empire in 1885, and they became part of German New Guinea that year, run by the trading companies doing business in the islands, particularly the Jaluit Company.[12] In World War I, the Empire of Japan occupied the Marshall Islands, which, in 1920, the League of Nations combined with other former German territories to form the South Seas Mandate. During World War II, the United States took control of the islands in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign in 1944. Nuclear testing began on Bikini Atoll in 1946 and concluded in 1958.

The U.S. government formed the Congress of Micronesia in 1965, a plan for increased self-governance of Pacific islands. The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in May 1979 provided independence to the Marshall Islands, whose constitution and president (Amata Kabua) were formally recognized by the US. Full sovereignty or self-government was achieved in a Compact of Free Association with the United States. Marshall Islands has been a member of the Pacific Community (SPC) since 1983 and a United Nations member state since 1991.[12] Politically, the Marshall Islands is a parliamentary republic with an executive presidency in free association with the United States, with the U.S. providing defense, subsidies, and access to U.S.-based agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission and the United States Postal Service. With few natural resources, the islands' wealth is based on a service economy, as well as fishing and agriculture; aid from the United States represents a large percentage of the islands' gross domestic product, but most financial aid from the Compact of Free Association expires in 2023.[14] As of June 2022, negotiations regarding an extension of the aid period were ongoing.[15] The country uses the United States dollar as its currency. In 2018, it also announced plans for a new cryptocurrency to be used as legal tender.[16][17]

The majority of the citizens of the Republic of Marshall Islands, formed in 1982, are of Marshallese descent, though there are small numbers of immigrants from the United States, China, Philippines, and other Pacific islands. The two official languages are Marshallese, which is one of the Oceanic languages, and English. Almost the entire population of the islands practices some religion: three-quarters of the country follows either the United Church of Christ – Congregational in the Marshall Islands (UCCCMI) or the Assemblies of God.[18]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Evidence suggests that around 3,000 years ago successive waves of human migrants from Southeast Asia spread across the Western Pacific Ocean, populating its many small islands. The Marshall Islands were settled by Micronesians in the 2nd millennium BC. Little is known of the islands' early history. Marshall Islanders, among the many great Oceanic voyagers, designed stick charts to map ocean swells and navigate between the islands.[19] Present-day seafaring, however, has remained an extension of maritime culture across the archipelago.

The Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar landed there in 1526, and the archipelago came to be known as "Los Pintados" ("The Painted (Ones)", possibly referring to the indigenous people first found there), "Las Hermanas" ("The Sisters") and "Los Jardines" ("The Gardens") within the Spanish Empire. It first fell within the jurisdiction of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and was then administered by Madrid, through the Captaincy General of the Philippines, upon the independence of Latin America and the dissolution of New Spain starting in 1821.

American whaling ships visited the islands in the 19th century. The first on record was the Awashonks in 1835 and last was the Andrews Hicks in 1905.[20]

The islands were only formally possessed by Spain for much of their colonial history, and on European maps were grouped with the Caroline Islands which today make up Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia,[21] or alternatively the "Nuevas Filipinas" ("New Philippines"). The islands were mostly left to their own affairs except for short-lived religious missions (documented in 1668 and 1731) during the 16th and 17th centuries. They were largely ignored by European powers except for cartographic demarcation treaties between the Iberian Empires (Portugal and Castilian Spain) in 1529, 1750 and 1777. The archipelago corresponding to the present-day country was independently named by Krusenstern, after British explorer John Marshall, who visited them together with Thomas Gilbert in 1788, en route from Botany Bay to Canton with two ships of the First Fleet, and started to establish German and British trading posts, which were not formally contested by Spain.

The Marshall Islands were formally claimed by Spain in 1874 through its capital in the East Indies, Manila. This marked the start of several strategic moves by the German Empire during the 1870s and 80s to annex them (claiming them to be "by chance unoccupied").[22] This policy culminated in a tense naval episode in 1885, which did not degenerate into a conflict due to the poor readiness of Spain's naval forces and the unwillingness for open military action from the German side.

Following papal mediation and German compensation of $4.5 million, Spain reached an agreement with Germany in 1885: the 1885 Hispano-German Protocol of Rome. This accord established a protectorate and set up trading stations on the islands of Jaluit (Joló) and Ebon to carry out the flourishing copra (dried coconut meat) trade. Marshallese Iroij (high chiefs) continued to rule under indirect colonial German administration, rendered tacitly effective by the wording in the 1885 Protocol, which demarcated an area subject to Spanish sovereignty (0-11ºN, 133-164ºE) omitting the Eastern Carolines, that is, the Marshall and Gilbert archipelagos, where most of the German trading posts were located.[23] The disputes were rendered moot after the selling of the whole Caroline archipelago to Germany 13 years later.[24]

At the beginning of World War I, Japan assumed control of the Marshall Islands. The Japanese headquarters was established at the German center of administration, Jaluit. On January 31, 1944, American forces landed on Kwajalein atoll and U.S. Marines and Army troops later took control of the islands from the Japanese on February 3, following intense fighting on Kwajalein and Enewetak atolls. In 1947, the United States, as the occupying power, entered into an agreement with the UN Security Council to administer much of Micronesia, including the Marshall Islands, as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

From 1946 to 1958, it served as the Pacific Proving Grounds for the United States and was the site of 67 nuclear tests on various atolls.[25] The world's first hydrogen bomb, codenamed "Mike", was tested at the Enewetak atoll in the Marshall Islands on November 1 (local date) in 1952, by the United States.[26]

Nuclear testing began in 1946 on Bikini Atoll after residents were evacuated. Over the years, 67 weapon tests were conducted, including the 15-megaton Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test, which produced significant fallout in the region. The testing concluded in 1958. Over the years, just one of over 60 islands was cleaned by the U.S. government, and the inhabitants are still waiting for the 2 billion dollars in compensation assessed by the Nuclear Claims Tribunal. Many of the islanders and their descendants still live in exile, as the islands remain contaminated with high levels of radiation.[27]

A significant radar installation was constructed on Kwajalein atoll.[28]

On May 1, 1979, in recognition of the evolving political status of the Marshall Islands, the United States recognized the constitution of the Marshall Islands and the establishment of the Government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The constitution incorporates both American and British constitutional concepts.

There have been a number of local and national elections since the Republic of the Marshall Islands was founded. The United Democratic Party, running on a reform platform, won the 1999 parliamentary election, taking control of the presidency and cabinet.

The islands signed a Compact of Free Association with the United States in 1986. Trusteeship was ended under United Nations Security Council Resolution 683 of December 22, 1990. Until 1999 the islanders received US$180M for continued American use of Kwajalein atoll, US$250M in compensation for nuclear testing, and US$600M in other payments under the compact.

Despite the constitution, the government was largely controlled by Iroij. It was not until 1999, following political corruption allegations, that the aristocratic government was overthrown, with Imata Kabua replaced by the commoner Kessai Note.

The Runit Dome was built on Runit Island to deposit U.S.-produced radioactive soil and debris, including lethal amounts of plutonium. There are ongoing concerns about deterioration of the waste site and a potential radioactive spill.[29]

In January 2020, David Kabua, son of founding president Amata Kabua, was elected as the new President of the Marshall Islands. His predecessor Hilda Heine lost the position after a vote.[30]

Since the late 1980s, Marshallese have migrated to the US, with over 4,000 in Arkansas and over 7,000 in Hawaii in the 2010 US Census.[31]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Marshall Islands sit atop ancient submerged volcanoes rising from the ocean floor, about halfway between Hawaii and Australia,[13] north of Nauru and Kiribati, east of the Federated States of Micronesia, and south of the disputed U.S. territory of Wake Island, to which it also lays claim.[32] The atolls and islands form two groups: the Ratak (sunrise) and the Ralik (sunset). The two island chains lie approximately parallel to one another, running northwest to southeast, comprising about 750,000 square miles (1,900,000 km2) of ocean but only about 70 square miles (180 km2) of land mass.[13] Each includes 15 to 18 islands and atolls.[33] The country consists of a total of 29 atolls and five individual islands situated in about 180,000 square miles (470,000 km2) of the Pacific.[32] The largest atoll with a land area of 6 square miles (16 km2) is Kwajalein. It surrounds a 655-square-mile (1,700 km2) lagoon.[34]

Twenty-four of the atolls and islands are inhabited. The remaining atolls are uninhabited due to poor living conditions, lack of rain, or nuclear contamination. The uninhabited atolls are:

- Ailinginae Atoll

- Bikar (Bikaar) Atoll

- Bikini Atoll

- Bokak Atoll

- Erikub Atoll

- Jemo Island

- Nadikdik Atoll

- Rongerik Atoll

- Toke Atoll

- Ujelang Atoll

The average altitude above sea level for the entire country is 7 feet (2.1 m).[32]

Shark sanctuary

In October 2011, the government declared that an area covering nearly 2,000,000 square kilometers (772,000 sq mi) of ocean shall be reserved as a shark sanctuary. This is the world's largest shark sanctuary, extending the worldwide ocean area in which sharks are protected from 2,700,000 to 4,600,000 square kilometers (1,042,000 to 1,776,000 sq mi). In protected waters, all shark fishing is banned and all by-catch must be released. However, some have questioned the ability of the Marshall Islands to enforce this zone.[35]

Territorial claim on Wake Island

The Marshall Islands also lays claim to Wake Island.[36] While Wake island has been administered by the United States since 1899, the Marshallese government refers to it by the name Ānen Kio (new orthography) or Enen-kio (old orthography).[37][38]

Climate

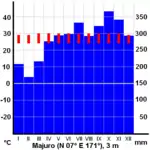

The climate has a relatively dry season from December to April and a wet season from May to November. Many Pacific typhoons begin as tropical storms in the Marshall Islands region, and grow stronger as they move west toward the Mariana Islands and the Philippines.

Population has outstripped the supply of fresh water, usually from rainfall. The northern atolls get 50 inches (1,300 mm) of rainfall annually; the southern atolls about twice that. The threat of drought is commonplace throughout the island chains.[39]

Climate change

Climate change is a serious threat to the Marshall Islands, with typhoons becoming stronger and sea levels rising. The sea around the Pacific islands has risen 0.28 inches (7 mm) a year since 1993, which is more than twice the rate of the worldwide average. In Kwajalein, there is a high risk of permanent flooding; when sea level rises to 3.3 feet (1 m), 37% of buildings will be permanently flooded in that scenario. In Ebeye, the risk of sea level rise is even higher, with 50% of buildings being permanently flooded in the same scenario. With 3.3 feet (1 m) of sea level rise, parts of the Majuro atoll will be permanently flooded and other parts are having a high risk of flooding especially the eastern part of the atoll would be significantly at risk. With 6.6 feet (2 m) sea level rise all the buildings of Majuro will be permanently flooded or would be at a high risk to be flooded.[40]

The per capita CO2 emissions were 2.56t in 2020.[41] The government of Marshall Islands pledged to be net zero in 2050, with a decrease of 32% decrease of GHGs in 2025, 45% decrease in 2030 and a 58% decrease in 2035 all compared to 2010 levels.[42]

Birds

Most birds found in the Marshall Islands, with the exception of those few introduced by man, are either sea birds or a migratory species.[43] There are about 70 species of birds, including 31 seabirds. 15 of these species actually nest locally. Sea birds include the black noddy and the white tern.[44] The only land bird is the house sparrow, introduced by humans.[45]

Marine

There are about 300 species of fish, 250 of which are reef fish.[44]

- Turtles: green turtles, hawksbill, Leatherback sea turtles, and Olive ridley sea turtles.[46]

- Sharks: There are at least 22 shark species including: Blue shark, Silky shark, Bigeye thresher shark, Pelagic thresher shark, Oceanic whitetip shark, and Tawny nurse shark.[47][48]

Arthropods

- Scorpions: dwarf wood scorpion, and Common house scorpion. Pseudoscorpions are occasionally found.[49]

- Spiders: Two: a scytodes, Dictis striatipes;[49] and Jaluiticola a genus of jumping spiders endemic to the Marshall Islands. Its only species is Jaluiticola hesslei.[50]

- Amphipod: One – Talorchestia spinipalma.[49]

- Orthoptera: cockroaches, American cockroaches, short-horned grasshopper, crickets.[49]

- Crabs include hermit crabs, and coconut crabs.[45]

Demographics

Historical population figures for the Marshall Islands are unknown. In 1862, the population of the Islands was estimated at 10,000.[33] In 1960, the population of the Islands was approximately 15,000. The 2011 Census counted 53,158 island residents. Over two-thirds of the residents of the Marshall Islands live in the capital city, Majuro, and the secondary urban center, Ebeye (located in Kwajalein Atoll). This figures excludes Marshall Islands natives who have relocated elsewhere; the Compact of Free Association allows them to freely relocate to the United States and obtain work there.[51][52] Approximately 4,300 Marshall Islands natives relocated to Springdale, Arkansas in the United States; this figure represents the largest population concentration of Marshall Islands natives outside their island home.[53]

Most residents of the Marshall Islands are Marshallese. Marshallese people are of Micronesian origin and are believed to have migrated from Asia to the Marshall Islands several thousand years ago. A minority of Marshallese have some recent Asian ancestry (mainly Japanese). About one-half of the nation's population lives in Majuro and Ebeye.[54][55][56][57]

The official languages of the Marshall Islands are English and Marshallese. Both languages are widely spoken.[58]

Religion

.jpg.webp)

Major religious groups in the Republic of the Marshall Islands include the United Church of Christ – Congregational in the Marshall Islands, with 51.5% of the population; the Assemblies of God, 24.2%; the Roman Catholic Church, 8.4%;[59] and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), 8.3%.[59] Also represented are Bukot Nan Jesus (also known as Assembly of God Part Two), 2.2%; Baptist, 1.0%; Seventh-day Adventists, 0.9%; Full Gospel, 0.7%; and the Baháʼí Faith, 0.6%.[59] Persons without any religious affiliation account for a very small percentage of the population.[59] Islam is also present through Ahmadiyya Muslim Community which is based in Majuro, with the first mosque opening in the capital in September 2012.[60]

Father A. Erdland,[61] a Catholic priest of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Hiltrup (German Empire, called in German Herz-Jesu-Missionare and in Latin Missionarii Sacratissimi Cordis), lived in Jaluit between 1904 and 1914. After doing considerable research on Marshallese culture and language, he published a 376-page monograph on the islands in 1914. Father H. Linckens,[62] another Sacred Heart missionary, visited the Marshall Islands in 1904 and 1911 for several weeks. In 1912 he published a small work on Catholic missionary activities and the people of the Marshall Islands. The Catholics are under the responsibility of the Apostolic Prefecture of the Marshall Islands (Praefectura Apostolica Insularum Marshallensium)[63] with headquarters at the Cathedral of the Assumption in Majuro, which was created by Pope John Paul II in 1993 through the papal bull Quo expeditius.

Health

During the Castle Bravo test of the first deployable thermonuclear bomb, a miscalculation resulted in the explosion being over twice as large as predicted. The nuclear fallout spread eastward onto the inhabited Rongelap and Rongerik Atolls. These islands were not evacuated before the explosion. Many of the Marshall Islands natives have since suffered from radiation burns and radioactive dusting, suffering the similar fates as the Japanese fishermen aboard the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, but have received little, if any, compensation from the federal government.[64]

Government

.jpg.webp)

The government of the Marshall Islands operates under a mixed parliamentary-presidential system as set forth in its 1979 Constitution.[65] Elections are held every four years in universal suffrage (for all citizens above 18), with each of the twenty-four constituencies (see below) electing one or more representatives (senators) to the lower house of RMI's unicameral legislature, the Nitijela. (Majuro, the capital atoll, elects five senators.) The President, who is head of state as well as head of government, is elected by the 33 senators of the Nitijela. Four of the five Marshallese presidents who have been elected since the Constitution was adopted in 1979 have been traditional paramount chiefs.[66]

.jpg.webp)

In January 2016, senator Hilda Heine was elected by Parliament as the first female president of the Marshall Islands; previous president Casten Nemra lost office after serving two weeks in a vote of no confidence.[12]

Legislative power lies with the Nitijela. The upper house of Parliament, called the Council of Iroij, is an advisory body comprising twelve paramount chiefs. The executive branch consists of the President and the Presidential Cabinet, which consists of ten ministers appointed by the President with the approval of the Nitijela. The twenty-four electoral districts into which the country is divided correspond to the inhabited islands and atolls. There are currently four political parties in the Marshall Islands: Aelon̄ Kein Ad (AKA), United People's Party (UPP), Kien Eo Am (KEA) and United Democratic Party (UDP). Rule is shared by the AKA and the UDP. The following senators are in the legislative body:

- Ailinglaplap Atoll – Christopher Loeak (AKA), Alfred Alfred, Jr. (IND)

- Ailuk Atoll – Maynard Alfred (UDP)

- Arno Atoll – Mike Halferty (KEA), Jejwadrik H. Anton (IND)

- Aur Atoll – Hilda C. Heine (AKA)

- Ebon Atoll – John M. Silk (UDP)

- Enewetak Atoll – Jack J. Ading (UPP)

- Jabat Island – Kessai H. Note (UDP)

- Jaluit Atoll – Casten Nemra (IND), Daisy Alik Momotaro (IND)

- Kili Island – Eldon H. Note (UDP)

- Kwajalein Atoll – Michael Kabua (AKA), David R. Paul (KEA), Alvin T. Jacklick (KEA)

- Lae Atoll – Thomas Heine (AKA)

- Lib Island – Jerakoj Jerry Bejang (AKA)

- Likiep Atoll – Leander Leander, Jr. (IND)

- Majuro Atoll – Sherwood M. Tibon (KEA), Anthony Muller (KEA), Brenson Wase (UDP), David Kramer (KEA), Kalani Kaneko (KEA)

- Maloelap Atoll – Bruce Bilimon (IND)

- Mejit Island – Dennis Momotaro (AKA)

- Mili Atoll – Wilbur Heine (AKA)

- Namdrik Atoll – Wise Zackhras (IND)

- Namu Atoll – Tony Aiseia (AKA)

- Rongelap Atoll – Kenneth A. Kedi (IND)

- Ujae Atoll – Atbi Riklon (IND)

- Utirik Atoll – Amenta Mathew (KEA)

- Wotho Atoll – David Kabua (AKA)

- Wotje Atoll – Litokwa Tomeing (UPP)

Foreign affairs and defense

The Compact of Free Association with the United States gives the U.S. sole responsibility for international defense of the Marshall Islands. It gives the islanders (the Marshallese) the right to emigrate to the United States without any visa.[68][52] But as aliens they can be placed in removal proceedings if convicted of certain criminal offenses.[52]

The Marshall Islands was admitted to the United Nations based on the Security Council's recommendation on August 9, 1991, in Resolution 704 and the General Assembly's approval on September 17, 1991, in Resolution 46/3.[69] In international politics within the United Nations, the Marshall Islands has often voted consistently with the United States with respect to General Assembly resolutions.[70]

On April 28, 2015, the Iranian navy seized the Marshall Island-flagged MV Maersk Tigris near the Strait of Hormuz. The ship had been chartered by Germany's Rickmers Ship Management, which stated that the ship contained no special cargo and no military weapons. The ship was reported to be under the control of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard according to the Pentagon. Tensions escalated in the region due to the intensifying of Saudi-led coalition attacks in Yemen. The Pentagon reported that the destroyer USS Farragut and a maritime reconnaissance aircraft were dispatched upon receiving a distress call from the ship Tigris and it was also reported that all 34 crew members were detained. US defense officials have said that they would review U.S. defense obligations to the Government of the Marshall Islands in the wake of recent events and also condemned the shots fired at the bridge as "inappropriate". It was reported in May 2015 that Tehran would release the ship after it paid a penalty.[71][72]

In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of the Marshall Islands and some other Pacific nations raising human rights violations in the Western New Guinea, which has been occupied by Indonesia since 1963,[73] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produce a report.[74][75] Indonesia rejected allegations.[75]

Since 1991 the Republic of Marshall Islands Sea Patrol, a division of Marshall Islands Police, has operated the 160 ton patrol vessel RMIS Lomor. Lomor is one of 22 Pacific Forum patrol vessels Australia provided to smaller nations in the Pacific Forum. While some other nations' missions for their vessels include sovereignty, protection, the terms of the Compact of Free Association restrict Lomor to civilian missions, like fishery protection and search and rescue.

In 2021, the governments of Australia and Japan decided to fund two major law enforcement developments of the Marshall Islands.[76]

In February 2021, the Marshall Islands announced it would be formally withdrawing from the Pacific Islands Forum in a joint statement with Kiribati, Nauru, and the Federated States of Micronesia after a dispute regarding Henry Puna's election as the Forum's secretary-general.[77][78]

Culture

Although the ancient skills are now in decline, the Marshallese were once able navigators, using the stars and stick-and-shell charts.

Sports

Major sports played in the Marshall Islands include volleyball, basketball (primarily by men), baseball, soccer and a number of water sports. The Marshall Islands has been represented at the Olympics at all games since the 2008 Beijing Olympics. In the 2020 Tokyo Olympics the Marshall Islands were represented by two swimmers.[79]

Association football

The Marshall Islands have a small club league, including Kobeer as the most successful club. One tournament was held by Play Soccer Make Peace. There is a small Football Association on the island of Majuro. The sport of association football in its growth is new to the Marshall Islands. The Marshall Islands does not yet have a national football team presently. The Marshall Islands is the only sovereign country in the world that does not have a record of a national football match.[80]

Marshall Islands Baseball / Softball Federation

Softball and baseball are held under one sports federation in the Marshall Islands. The President is Jeimata Nokko Kabua. Both sports are growing at a fast pace with hundreds of Marshallese people behind the Marshall Islands Baseball / Softball Federation. The Marshall Islands achieved a silver medal in the Micronesian Games in 2012, as well as medals in the SPG Games.[81]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

The islands have few natural resources, and their imports far exceed exports. According to the CIA, the value of exports in 2013 was approximately $53.7 million while estimated imports were $133.7 million. Agricultural products include coconuts, tomatoes, melons, taro, breadfruit, fruits, pigs and chickens. Industry is made of the production of copra and craft items, tuna processing and tourism. The GDP in 2016 was an estimated $180 million, with a real growth rate of 1.7%. The GDP per capita was $3,300.[82]

The International Monetary Fund reported in mid-2016 that the economy of the Republic had expanded by about 0.5 percent in the Fiscal Year 2015 thanks to an improved fisheries sector. A surplus of 3% of GDP was recorded "owing to record-high fishing license fees. Growth is expected to rise to about 1.5 percent and inflation to about 0.5 percent in FY2016, as the effects of the drought in earlier 2016 are offset by the resumption of infrastructure projects."[83]

In 2018, the Republic of Marshall Islands passed the Sovereign Currency Act, which made it the first country to issue their own cryptocurrency and certify it as legal tender; the currency is called the "Sovereign".[84][85]

Shipping

The Marshall Islands plays a vital role in the international shipping industry as a flag of convenience for commercial vessels.[86] The Marshallese registry began operations in 1990, and is managed through a joint venture with International Registries, Inc., a US-based corporation that has offices in major shipping centers worldwide.[87] As of 2017, the Marshallese ship registry was the second largest in the world, after that of Panama.[88]

Unlike some flag countries, there is no requirement that a Marshallese flag vessel be owned by a Marshallese individual or corporation. Following the 2015 seizure of the MV Maersk Tigris, the United States announced that its treaty obligation to defend the Marshall Islands did not extend to foreign-owned Marshallese flag vessels at sea.[89]

As a result of ship-to-ship transfers by Marshallese flag tanker vessels, the Marshall Islands have statistically been one of the largest importers of crude oil from the United States, despite the fact that the islands have no oil refining capacity.[90]

Labor

In 2007, the Marshall Islands joined the International Labour Organization, which means its labor laws will comply with international benchmarks. This may affect business conditions in the islands.[91]

Taxation

The income tax has two brackets, with rates of 8% and 12%.[92] The corporate tax is 3% of revenue.[92]

Foreign assistance

United States government assistance is the mainstay of the economy. Under terms of the Amended Compact of Free Association, the U.S. is committed to provide US$57.7 million per year in assistance to the Marshall Islands (RMI) through 2013, and then US$62.7 million through 2023, at which time a trust fund, made up of U.S. and RMI contributions, will begin perpetual annual payouts.[93]

The United States Army maintains the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Kwajalein Atoll. Marshallese land owners receive rent for the base.

Agriculture

.jpg.webp)

Agricultural production is concentrated on small farms.[94] The most important commercial crop is copra,[95][96] followed by coconut, breadfruit, pandanus, banana, taro and arrowroot. The livestock consists primarily of pigs and chickens.[97][83]

Fishing

Majuro is the world's busiest tuna transshipment port, with 704 transshipments totaling 444,393 tons in 2015.[99] Majuro is also a tuna processing center; the Pan Pacific Foods plant exports processed tuna to a number of countries, primarily the United States under the Bumble Bee brand.[100] Fishing license fees, primarily for tuna, provide noteworthy income for the government.[83]

In 1999, a private company built a tuna loining plant with more than 400 employees, mostly women. But the plant closed in 2005 after a failed attempt to convert it to produce tuna steaks, a process that requires half as many employees. Operating costs exceeded revenue, and the plant's owners tried to partner with the government to prevent closure. But government officials personally interested in an economic stake in the plant refused to help. After the plant closed, it was taken over by the government, which had been the guarantor of a $2 million loan to the business.

Energy

On September 15, 2007, Witon Barry (of the Tobolar Copra processing plant in the Marshall Islands capital of Majuro) said power authorities, private companies, and entrepreneurs had been experimenting with coconut oil as alternative to diesel fuel for vehicles, power generators, and ships. Coconut trees abound in the Pacific's tropical islands. Copra, the meat of the coconut, yields coconut oil (1 liter for every 6 to 10 coconuts).[101] In 2009, a 57 kW solar power plant was installed, the largest in the Pacific at the time, including New Zealand.[102] It is estimated that 330 kW of solar and 450 kW of wind power would be required to make the College of the Marshall Islands energy self-sufficient.[103] Marshalls Energy Company (MEC), a government entity, provides the islands with electricity. In 2008, 420 solar home systems of 200 Wp each were installed on Ailinglaplap Atoll, sufficient for limited electricity use.[104]

Education

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI)[105] finds that the Marshall Islands are fulfilling only 66.1% of what it should be fulfilling for the right to education based on the country's level of income.[106] HRMI breaks down the right to education by looking at the rights to both primary education and secondary education. While taking into consideration the Marshall Islands' income level, the nation is achieving 65.5% of what should be possible based on its resources (income) for primary education and 66.6% for secondary education.[106]

The Ministry of Education is the education agency of the islands. Marshall Islands Public School System operates the state schools in the Marshall Islands.

In the 1994–1995 school year the country had 103 elementary schools and 13 secondary schools. There were 27 private elementary schools and one private high school. Christian groups operated most of the private schools.[107]

Historically the Marshallese population was taught in English first with Marshallese instruction coming later, but this was reversed in the 1990s to keep the islands' cultural heritage and so children could write in Marshallese. Now English language instruction begins in grade 3. Christine McMurray and Roy Smith wrote in Diseases of Globalization: Socioeconomic Transition and Health that this could potentially weaken the children's English skills.[107]

There are two tertiary institutions operating in the Marshall Islands, the College of the Marshall Islands[108] and the University of the South Pacific.

Transportation

The Marshall Islands are served by the Marshall Islands International Airport in Majuro, the Bucholz Army Airfield in Kwajalein, and other small airports and airstrips.[109]

Airlines include United Airlines, Nauru Airlines, Air Marshall Islands, and Asia Pacific Airlines.[110]

Media and communications

The Marshall Islands have several AM and FM radio stations. AM stations are 1098 5 kW V7AB Majuro (Radio Marshalls, national coverage) and 1224 AFN Kwajalein (both public radio) as well as 1557 Micronesia Heatwave. The FM stations are 97.9 V7AD Majuro,[111] V7AA 96.3 FM Uliga[112] and 104.1 V7AA Majuro (Baptist religious). BBC World is broadcast on 98.5 FM Majuro.[113] The most recent station is Power 103.5 which started broadcasting in 2016.[114]

AFRTS stations include 99.9 AFN Kwajalein (country), 101.1 AFN (adult rock) and 102.1 AFN (hot AC).[115][116]

There is one broadcast television station, MBC-TV operated by the state.[117] Cable TV is available. On cable TV, most programs are shown two weeks later than in North America but news in real time can be viewed on CNN, CNBC and BBC.[118] American Forces Radio and Television also provides TV service to Kwajalein Atoll.[119]

The Marshall Islands National Telecommunications Authority (NTA) provides telephone, cable TV (MHTV), FAX, cellular and Internet services.[120][121] The Authority is a private corporation with significant ownership by the national government.[122]

See also

- Outline of the Marshall Islands

- Index of Marshall Islands–related articles

- List of islands of the Marshall Islands

- Pacific Proving Grounds

- List of island countries

- The Plutonium Files

- Visa policy of the Marshall Islands

Notes

- Pronunciations:

* English: Republic of the Marshall Islands /ˈmɑːrʃəl ˈaɪləndz/ ( listen)

listen)

* Marshallese: Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ ([ɑɔlʲɛbʲænʲɑːorˠɤɡinʲ(i)mˠɑːzʲɛlˠ]) - Wake Island is claimed as a territory of the Marshall Islands, but is also claimed as an unorganized, unincorporated territory of the United States, with de facto control vested in the Office of Insular Affairs (and all military defenses managed by the United States military).

References

- The largest cities in Marshall Islands, ranked by population Archived September 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. population.mongabay.com. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- "Marshall Islands Geography". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- "Religions in Marshall Islands | PEW-GRF". Globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- "Members". rmiparliament.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands population (2022) live — Countrymeters". Countrymeters.info. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands 2011 Census Report" (PDF). Prism.spc.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. September 8, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- "Marshall Islands". marshallese.org. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- "Population, total - Marshall Islands". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- "Marshall Islands Population (2017) - Worldometers". Worldometers.info. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- "Marshall Islands profile - Timeline". Bbc.com. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands". Pacific RISA. February 3, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands country brief". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Australia. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- Martina, Michael; Brunnstrom, David (June 17, 2022). "U.S. and Marshall Islands seek economic assistance deal this year". Reuters. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- Liao, Shannon (May 23, 2018). "The Marshall Islands replaces the U.S. dollar with its own cryptocurrency". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude (February 28, 2018). "Marshall Islands to issue own sovereign cryptocurrency". Technology News. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "Marshall Islands" (PDF). imr.ptc.ac.fj. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- Ratzel, Friedrich. "The History of Mankind". inquirewithin.biz. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2019., Book II, Section A, The Races of Oceania page 165, picture of a stick chart from the Marshall Islands. MacMillan and Co.

- Langdon, Robert (1984), Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific Ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, p.177 & 179. ISBN 086784471X

- "Carolinas". Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Palacio Atard, Vicente (1969). "LA CUESTION DE LAS ISLAS CAROLINAS. UN CONFLICTO ENTRE ESPAÑA Y LA ALEMANIA BISMARCKIANA" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2018.

- Corral, Carlos (1995). El conflicto sobre las Islas Carolinas entre España y Alemania (1885): la mediación internacional de León XIII. Editorial Complutense. ISBN 9788474914849.

- "Caroline Islands | Encyclopedia.com". encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "Marshall Islands marks 71 years since start of U.S. nuclear tests on Bikini". Radio New Zealand. March 1, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "What the First H-Bomb Test Looked Like". Time. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- France-Press, Agence (March 1, 2014). "Bikini Atoll nuclear test: 60 years later and islands still unliveable". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Rising seas could threaten $1 billion Air Force radar site". cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster". Los Angeles Times. November 10, 2019. Archived from the original on November 14, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "New president for Marshall Islands". RNZ.co.nz. January 6, 2020. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

- "Geography". Rmiembassyus.org. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Beardslee, L. A. (1870). Marshall Group. North Pacific Islands. Publications.no. 27. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 33. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- Alcalay, Glenn; Fuchs, Andrew. "History of the Marshall Islands". atomicatolls.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Vast shark sanctuary created in Pacific". BBC News. October 3, 2011. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- Wake Island Archived 2021-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Enen Kio (a.k.a. Wake Island) • Marshall Islands Guide". Marshall Islands Guide. December 16, 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "Dictionary: ānen Kio". marshallese.org. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- Peter Meligard (December 28, 2015). "Perishing oO Thirst In A Pacific Paradise". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- "Adapting to rising sea levels in Marshall Islands". ArcGIS StoryMaps. October 22, 2021. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (May 11, 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- "The Republic of the Marshall Islands Nationally Determined Contribution" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- Bryan, Edwin Horace (1965). Life in Micronesia. Kwajalein, Marshall Islands: Kwajalein Hourglass. OCLC 21662705.

- "Animals in Marshall Islands". Listofcountriesoftheworld.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Kwajalein Atoll Causeway Project, Marshall Islands, USA Permit Application, Discharge of Fill Material: Environmental Impact Statement". August 22, 1986. p. 23. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- MIMRA. 2008, 2009, 2010. Republic of the Marshall Islands Annual Report Part 1. Information of Fisheries, Statistics and Research. Annual Report to the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Scientific Committee Fourth Regular Session. WCPFC-SC4-AR/CCM-12. Oceanic and Industrial Affairs Division, Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Majuro

- Bromhead, D., Clarke, S., Hoyle, S., Muller, B., Sharples, P., Harley, S. 2012. Identification of factors influencing shark catch and mortality in the Marshall Islands tuna longline fishery and management implications. Journal of Fish Biology 80: 1870-1894

- dos Reis, M.A.F. (2005). "Chondrichthyan Fauna from the Pirabas Formation, Miocene of Northern Brazil, with Comments on Paleobiogeography". Anuário do Instituto de Geociências. 28 (2): 31–58. doi:10.11137/2005_2_31-58.

- Bryan, E.H. (1965). Life in Micronesia: Marshall Island Insects, Part 1. Kwajalein, Marshall Islands: Kwajalein Hourglass.

- "Salticidae". World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Gwynne, S.C. (October 5, 2012). "Paradise With an Asterisk". Outside Magazine. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- "Bryan Maie V. Merrick Garland, No. 19-73099" (PDF). U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. August 2, 2021. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

Bryan Maie is a native and citizen of the Marshall Islands who came to the United States as a child with his family in 1989. Maie and his family arrived in Hawaii pursuant to the Compact of Free Association, which allows citizens of the Marshall Islands to come to the United States to live, work, and go to school without a visa.

- Schulte, Bret (July 4, 2012). "For Pacific Islanders, Hopes and Troubles in Arkansas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- David Vine (2006). "The Impoverishment of Displacement: Models for Documenting Human Rights Abuses and the People of Diego Garcia" (PDF). Human Rights Brief. 13 (2): 21–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2013.

- David Vine (January 7, 2004) Exile in the Indian Ocean: Documenting the Injuries of Involuntary Displacement. Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies. Web.gc.cuny.edu. Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- David Vine (2006). Empire's Footprint: Expulsion and the United States Military Base on Diego Garcia. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-542-85100-1.

- David Vine (2011). Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (New in Paper). Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-691-14983-7.

- "The World Factbook: Marshall Islands". cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. June 28, 2017. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2017. Look under tab for "People and Society".

- International Religious Freedom Report 2009: Marshall Islands . United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- First Mosque opens up in Marshall Islands Archived October 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine by Radio New Zealand International, September 21, 2012

- Annals of the Propagation of the Faith. Society for the Propagation of the Faith. 1910.

- Spennemann, Dirk R. (1990). Cultural Resource Management Plan for Majuro Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands: Management plan. U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Territorial and Insular Affairs.

- "Marshall Islands (Prefecture Apostolic) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- Renee Lewis (July 28, 2015). "Bikinians evacuated 'for good of mankind' endure lengthy nuclear fallout". Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- "Constitution of the Marshall Islands". Paclii.org. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Giff Johnson (November 25, 2010). "Huge funeral recognizes late Majuro chief". Marianas Variety News & Views. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- Amanda Levasseur, Sara Muir (August 1, 2018). "USCGC Oliver Berry crew sets new horizons for cutter operations". Dvidshub. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

In July Oliver Berry's crew set a new milestone by deploying over the horizon to the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The 4,400 nautical mile trip marked marking the furthest deployment of an FRC to date for the Coast Guard and is the first deployment of its kind in the Pacific.

- Davenport, Coral; Haner, Josh (December 1, 2015). "The Marshall Islands Are Disappearing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/3, Admission of the Republic of the Marshall Islands to Membership in the United Nations, adopted September 17, 1991". un.org. United Nations Official Document. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015.

- General Assembly – Overall Votes – Comparison with U.S. vote Archived 2019-12-02 at the Wayback Machine lists the Marshall Islands as the country with the second highest incidence of votes. Micronesia has always been in the top two.

- Armin Rosen (April 29, 2015). "Marshall Islands ship seized by Iran – Business Insider". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 3, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Iran to release cargo vessel after it pays fine – Business Insider". Business Insider. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- "Freedom of the press in Indonesian-occupied West Papua". The Guardian. July 22, 2019. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Fox, Liam (March 2, 2017). "Pacific nations call for UN investigations into alleged Indonesian rights abuses in West Papua". ABC News. Archived from the original on October 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- "Pacific nations want UN to investigate Indonesia on West Papua". SBS News. March 7, 2017. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Johnson, Giff (February 1, 2021). "Australia, Japan fund law enforcement in Marshall Islands | MVariety". mvariety.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "Five Micronesian countries leave Pacific Islands Forum". RNZ. February 9, 2021. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- "Pacific Islands Forum in crisis as one-third of member nations quit". The Guardian. February 8, 2021. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- "Team Marshall Islands Marshall Islands - Profile". Olympics.com. July 27, 2021. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Football". oceaniafootball.hpage.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- "Marshall Islands Baseball / Softball Federation - Marshall Islands National Olympic Committee - SportsTG". SportsTG. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- "Marshall Islands Economy 2017, CIA World Factbook". Theodora.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands : 2016 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Republic of the Marshall Islands". Imf.org. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands to issue own sovereign cryptocurrency". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- "Unlocking the potential of blockchain technology". MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- Galbraith, Kate (June 3, 2015). "Marshall Islands, the Flag for Many Ships, Seeks to Rein In Emissions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Marshall Islands - The Shipping Law Review - Edition 4 - The Law Reviews". thelawreviews.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Hand, Marcus (March 22, 2017). "Marshall Islands becomes the world's second largest ship registry". Seatrade Maritime News. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Kopel, David (May 1, 2015). "U.S. treaty obligation to defend Marshall Islands ships". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Gloystein, Henning (August 12, 2016). "How the Marshall Islands became a top U.S. crude export destination". Intel. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands becomes 181st ILO member State". Ilo.org. July 6, 2007. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008.

- "Official Homepage of the NITIJELA (PARLIAMENT)". NITIJELA (PARLIAMENT) of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- "COMPACT OF FREE ASSOCIATION AMENDMENTS ACT OF 2003" (PDF). Public Law 108–188, 108th Congress. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2007.

- Mellgard, Peter (December 12, 2015). "In The Marshall Islands, Traditional Agriculture And Healthy Eating Are A Climate Change Strategy". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "Copra Processing Plant • Marshall Islands Guide". Infomarshallislands.com. November 18, 2016. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Copra production up on 2014 - The Marshall Islands Journal". Marshallislandsjournal.com. October 9, 2015. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Speedy, Andrew. "Marshall Islands". Fao.org. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands". United States Department of State. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- "Marshall Islands' Majuro is world's tuna hub". Undercurrent News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Majuro Tuna Plant Exports World-Wide". U.S. Embassy in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. November 23, 2012. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- "Pacific Islands look to coconut power to fuel future growth". September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- College of the Marshall Islands Archived February 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. (PDF) . reidtechnology.co.nz. June 2009

- College of the Marshall Islands: Reiher Returns from Japan Solar Training Program with New Ideas Archived October 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Yokwe.net. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands". Rep5.eu. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Human Rights Measurement Initiative – The first global initiative to track the human rights performance of countries". humanrightsmeasurement.org. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- "Marshall Islands - HRMI Rights Tracker". rightstracker.org. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- McMurray, Christine; Smith, Roy (October 11, 2013). Diseases of Globalization: Socioeconomic Transition and Health. Routledge. ISBN 9781134200221.

- College of the Marshall Islands (CMI) Archived April 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Cmi.edu. Retrieved on September 11, 2013.

- "Republic of the Marshall Islands – Amata Kabua International Airport". Republic of the Marshall Islands Ports Authority. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Airlines Serving the Marshall Islands - RMIPA". Rmipa.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Radio Majuro 979 - Listen Radio Majuro 979 online radio FM - Marshall Islands". Topradiofree.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "V7AA - 96.3 FM Uliga Radio Online". radio.gjoy24.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands country profile". Bbc.com. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Hot Radio Station • Marshall Islands Guide". Infomarshallislands.com. September 27, 2016. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands: Radio Station Listings". Radiostationworld.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Micronesia Heatwave 1557 - Listen Micronesia Heatwave 1557 online radio FM - Marshall Islands". Topradiofree.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands profile - Media". Bbc.com. July 31, 2012. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Marshall Islands facts, information, pictures - Encyclopedia.com articles about Marshall Islands". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "AUSTRALIA-OCEANIA : MARSHALL ISLANDS". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Internet Options • Marshall Islands Guide". Infomarshallislands.com. June 11, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Hasegawa. "MHTV". Ntamar.net. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Hasegawa. "About Us". Minta.mh. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Home". marshallislandsjournal.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Pacific Islands Newspapers : Marshall Islands". University of Hawaii at Manoa. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

Bibliography

- Sharp, Andrew (1960). Early Spanish Discoveries in the Pacific.

Further reading

- Barker, Holly M. (February 1, 2012). Bravo for the Marshallese: Regaining Control in a Post-Nuclear, Post-Colonial World. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781111833848.

- Carucci, Laurence Marshall (1997). Nuclear Nativity: Rituals of Renewal and Empowerment in the Marshall Islands. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780875802176.

- Hein, J. R., F. L. Wong, and D. L. Mosier (2007). Bathymetry of the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Vicinity. Miscellaneous Field Studies; Map-MF-2324. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- Niedenthal, Jack (2001). For the Good of Mankind: A History of the People of Bikini and Their Islands. Bravo Publishers. ISBN 9789829050021.

- Rudiak-Gould, Peter (2009). Surviving Paradise: One Year on a Disappearing Island. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 9781402766640.

- Woodard, Colin (2000). Ocean's End: Travels Through Endangered Seas. New York: Basic Books. (Contains extended account of sea-level rise threat and the legacy of U.S. Atomic testing.)

External links

Government

- Embassy of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Washington, DC official government site

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

General information

- Marshall Islands. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Country Profile from New Internationalist

- Marshall Islands from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Marshall Islands at Curlie

- Marshall Islands from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of the Marshall Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of the Marshall Islands

News media

- Marshall Islands Journal Weekly independent national newspaper

Other

- Digital Micronesia – Marshalls by Dirk HR Spennemann, Associate Professor in Cultural Heritage Management

- Plants & Environments of the Marshall Islands Book turned website by Dr. Mark Merlin of the University of Hawaii

- Atomic Testing Information

- Pictures of victims of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands on Nuclear Files.org

- "Kenner hearing: Marshall Islands-flagged rig in Gulf oil spill was reviewed in February"

- NOAA's National Weather Service – Marshall Islands

- Canoes of the Marshall Islands

- Alele Museum – Museum of the Marshall Islands

- WUTMI – Women United Together Marshall Islands

.svg.png.webp)