Islam

Islam (/ˈɪslɑːm/;[lower-alpha 1] Arabic: الإسلام, al-ʿIslām [ɪsˈlaːm] (![]() listen), transl. "Submission [to God]")[7][8] is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims[9] to be the direct word of God (or Allah) as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main and final Islamic prophet.[10][11] It is the world's second-largest religion behind Christianity, with its followers ranging between 1-1.8 billion globally, or around a quarter of the world's population.[6][12][13] Islam teaches that God is merciful, all-powerful, and unique,[14] and has guided humanity through various prophets, revealed scriptures, and natural signs, with the Quran serving as the final and universal revelation and Muhammad serving as the "Seal of the Prophets" (the last prophet of God).[11][15] The teachings and practices of Muhammad (sunnah) documented in traditional collected accounts (hadith) provide a secondary constitutional model for Muslims to follow after the Quran.[16]: 63

listen), transl. "Submission [to God]")[7][8] is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims[9] to be the direct word of God (or Allah) as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main and final Islamic prophet.[10][11] It is the world's second-largest religion behind Christianity, with its followers ranging between 1-1.8 billion globally, or around a quarter of the world's population.[6][12][13] Islam teaches that God is merciful, all-powerful, and unique,[14] and has guided humanity through various prophets, revealed scriptures, and natural signs, with the Quran serving as the final and universal revelation and Muhammad serving as the "Seal of the Prophets" (the last prophet of God).[11][15] The teachings and practices of Muhammad (sunnah) documented in traditional collected accounts (hadith) provide a secondary constitutional model for Muslims to follow after the Quran.[16]: 63

| Islam | |

|---|---|

| الاسلام al-’Islām | |

| |

| Type | Universal religion |

| Classification | Abrahamic |

| Scripture | Quran |

| Theology | Monotheism |

| Language | Classical Arabic |

| Territory | Muslim world |

| Founder | Muhammad |

| Origin | 7th century CE Jabal al-Nour, near Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Separations | Ahl-e Haqq,[1] Bábism,[2] Baháʼí Faith,[3] Din-i Ilahi, Druzism[4][5] |

| Members | c. 2 billion[6] (referred to as Muslims, who comprise the ummah) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Muslims believe that Islam is the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed many times through earlier prophets such as Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, among others;[17] these earlier revelations are attributed to Judaism and Christianity, which are regarded in Islam as spiritual predecessor faiths.[18] They also consider the Quran, when preserved in Classical Arabic, to be the unaltered and final revelation of God to humanity.[19] Like other Abrahamic religions, Islam also teaches of a "Final Judgement" wherein the righteous will be rewarded in paradise (Jannah) and the unrighteous will be punished in hell (Jahannam).[20] Religious concepts and practices include the Five Pillars of Islam—considered obligatory acts of worship—and following Islamic law (sharia), which touches on virtually every aspect of life, from banking and finance and welfare to women's roles and the environment.[21][22] The cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem are home to the three holiest sites in Islam, in descending order: Masjid al-Haram, Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, and Al-Aqsa Mosque, respectively.[23]

Islam originated in the 7th century at Jabal al-Nour, a mountain peak near Mecca where Muhammad's first revelation is said to have taken place.[24] Through various caliphates, the religion later spread outside of Arabia shortly after Muhammad's death, and by the 8th century, the Umayyad Caliphate had imposed Islamic rule from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Indus Valley in the east. The Islamic Golden Age refers to the period traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century, during the reign of the Abbasid Caliphate, when much of the Muslim world was experiencing a scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing.[25][26][27] The expansion of the Muslim world involved various states and caliphates as well as extensive trade and religious conversion as a result of Islamic missionary activities (dawah).[28]: 125–258

There are two major Islamic denominations: Sunni Islam (85–90 percent)[29] and Shia Islam (10–15 percent);[30][31][32] combined, they make up a majority of the population in 49 countries.[33][34] While Sunni–Shia differences initially arose from disagreements over the succession to Muhammad, they grew to cover a broader dimension both theologically and juridically, with the divergence acquiring notable political significance.[35] Approximately 12 percent of the world's Muslims live in Indonesia, the most populous Muslim-majority country;[36] 31 percent live in South Asia;[37] 20 percent live in the Middle East–North Africa; and 15 percent live in sub-Saharan Africa.[38] Sizable Muslim communities are also present in the Americas, China, and Europe.[39][40]

Etymology

In Arabic, Islam (Arabic: إسلام, lit. 'submission [to God]') is the verbal noun originating from the verb سلم (salama), from triliteral root س-ل-م (S-L-M), which forms a large class of words mostly relating to concepts of wholeness, submission, sincerity, safeness, and peace.[41] Islam is the verbal noun of Form IV of the root and means "submission" or "total surrender". In a religious context, it means "total surrender to the will of God".[42][43] A Muslim (مُسْلِم), the word for a follower of Islam, is the active participle of the same verb form, and means "submitter (to God)" or "one who surrenders (to God)". The word Islam ("submission") sometimes has distinct connotations in its various occurrences in the Quran. Some verses stress the quality of Islam as an internal spiritual state: "Whoever God wills to guide, He opens their heart to Islam."[lower-roman 1][43] The word silm (سِلْم) in Arabic means both peace and also the religion of Islam.[44] A common linguistic phrase demonstrating its usage is "he entered into as-silm" (دَخَلَ فِي السِّلْمِ) which means "he entered into Islam," with a connotation of finding peace by submitting one's will to the Will of God.[44] The word Islam can be used in a linguistic sense of submission or in a technical sense of the religion of Islam, which also is called as-silm which means peace.[44] In the Hadith of Gabriel, Islam is presented as one part of a triad that also includes imān (faith), and ihsān (excellence).[45][46]

Islam itself was historically called Mohammedanism in the English-speaking world. This term has fallen out of use and is sometimes said to be offensive, as it suggests that a human being, rather than God, is central to Muslims' religion, parallel to Buddha in Buddhism.[47] Some authors, however, continue to use the term Mohammedanism as a technical term for the religious system as opposed to the theological concept of Islam that exists within that system.

Articles of faith

The Islamic creed (aqidah) requires belief in six articles: God, angels, books, prophets, the Day of Resurrection, and the divine decree.

God

Part of a series on Islam |

| God in Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The central concept of Islam is tawḥīd (Arabic: توحيد), the oneness of God. Usually thought of as a precise monotheism, but also panentheistic in Islamic mystical teachings.[48][49][50][51] God is seen as incomparable and without partners such as in the Christian Trinity,[52] and associating partners to God or attributing God's attributes to others is seen as idolatory, called shirk. God is seen as transcendent of creation and so is beyond comprehension. Thus, Muslims are not iconodules and do not attribute forms to God. God is instead described and referred to by several names or attributes, the most common being Ar-Rahmān (الرحمان) meaning "The Entirely Merciful," and Ar-Rahīm (الرحيم) meaning "The Especially Merciful" which are invoked at the beginning of most chapters of the Quran.[53][54]

Islam teaches that the creation of everything in the universe was brought into being by God's command as expressed by the wording, "Be, and it is,"[lower-roman 2][55] and that the purpose of existence is to worship God.[56] He is viewed as a personal god[55] and there are no intermediaries, such as clergy, to contact God. Consciousness and awareness of God is referred to as Taqwa. Allāh is a term with no plural or gender being ascribed to it and is also used by Muslims and Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews in reference to God, whereas ʾilāh (إله) is a term used for a deity or a god in general.[57][58][59] Other non-Arab Muslims might use different names as much as Allah, for instance Tanrı in Turkish or Khodā in Persian.

Angels

Angels (Arabic: ملك}}, malak) are beings described in the Quran[60] and hadith.[61] They are described as created to worship God and also to serve other specific duties such as communicating revelations from God, recording every person's actions, and taking a person's soul at the time of death. They are described as being created variously from 'light' (nūr)[62][63][64] or 'fire' (nār).[65][66][67][68] Islamic angels are often represented in anthropomorphic forms combined with supernatural images, such as wings, being of great size or wearing heavenly articles.[69][70][71][72] Common characteristics for angels are their missing needs for bodily desires, such as eating and drinking.[73] Some of them, such as Gabriel and Michael, are mentioned by name in the Quran. Angels play a significant role in the literature about the Mi'raj, where Muhammad encounters several angels during his journey through the heavens.[61] Further angels have often been featured in Islamic eschatology, theology and philosophy.[74]

Books

The Islamic holy books are the records that Muslims believe various prophets received from God through revelations, called wahy. Muslims believe that parts of the previously revealed scriptures, such as the Tawrat (Torah) and the Injil (Gospel), had become distorted—either in interpretation, in text, or both,[75][76][77][78][79][80] while the Quran (lit. 'Recitation')[81][82][83] is viewed as the final, verbatim and unaltered word of God.

Muslims believe that the verses of the Quran were revealed to Muhammad by God, through the archangel Gabriel (Jibrīl), on multiple occasions between 610 CE and 632, the year Muhammad died.[84] While Muhammad was alive, these revelations were written down by his companions, although the prime method of transmission was orally through memorization.[85] The Quran is divided into 114 chapters (suras) which combined contain 6,236 verses (āyāt). The chronologically earlier chapters, revealed at Mecca, are concerned primarily with spiritual topics while the later Medinan chapters discuss more social and legal issues relevant to the Muslim community.[55][81] Muslim jurists consult the hadith ('accounts'), or the written record of Prophet Muhammad's life, to both supplement the Quran and assist with its interpretation. The science of Quranic commentary and exegesis is known as tafsir.[86][87] The set of rules governing proper elocution of recitation is called tajwid. In addition to its religious significance, it is widely regarded as the finest work in Arabic literature,[88][89] and has influenced art and the Arabic language.[90]

Prophets

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

|

Prophets (Arabic: أنبياء, anbiyāʾ) are believed to have been chosen by God to receive and preach a divine message. Additionally, a prophet delivering a new book to a nation is called a rasul (رسول, rasūl), meaning "messenger".[91] Muslims believe prophets are human and not divine. All of the prophets are said to have preached the same basic message of Islam – submission to the will of God – to various nations in the past and that this accounts for many similarities among religions. The Quran recounts the names of numerous figures considered prophets in Islam, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus, among others.[55]

Muslims believe that God sent Muhammad as the final prophet ("Seal of the prophets") to convey the completed message of Islam. In Islam, the "normative" example of Muhammad's life is called the sunnah (literally "trodden path"). Muslims are encouraged to emulate Muhammad's moral behaviors in their daily lives, and the Sunnah is seen as crucial to guiding interpretation of the Quran.[92][93][94] This example is preserved in traditions known as hadith, which are accounts of his words, actions, and personal characteristics. Hadith Qudsi is a sub-category of hadith, regarded as God's verbatim words quoted by Muhammad that are not part of the Quran. A hadith involves two elements: a chain of narrators, called sanad, and the actual wording, called matn. There are various methodologies to classify the authenticity of hadiths, with the commonly used grading being: "authentic" or "correct" (صحيح, ṣaḥīḥ); "good", hasan (حسن, ḥasan); or "weak" (ضعيف, ḍaʻīf), among others. The Kutub al-Sittah are a collection of six books, regarded as the most authentic reports in Sunni Islam. Among them is Sahih al-Bukhari, often considered by Sunnis to be one of the most authentic sources after the Quran.[95] Another famous source of hadiths is known as The Four Books, which Shias consider as the most authentic hadith reference.[96][97][98]

Resurrection and judgment

Belief in the "Day of Resurrection" or Yawm al-Qiyāmah (Arabic: يوم القيامة), is also crucial for Muslims. It is believed that the time of Qiyāmah is preordained by God but unknown to man. The Quran and the hadith, as well as in the commentaries of scholars, describe the trials and tribulations preceding and during the Qiyāmah. The Quran emphasizes bodily resurrection, a break from the pre-Islamic Arabian understanding of death.[99][100][101]

On Yawm al-Qiyāmah, Muslims believe all humankind will be judged by their good and bad deeds and consigned to Jannah (paradise) or Jahannam (hell). The Quran in Surat al-Zalzalah describes this as: "So whoever does an atom's weight of good will see it. And whoever does an atom's weight of evil will see it." The Quran lists several sins that can condemn a person to hell, such as disbelief in God (كفر, kufr), and dishonesty. However, the Quran makes it clear that God will forgive the sins of those who repent if he wishes. Good deeds, like charity, prayer, and compassion towards animals,[102][103] will be rewarded with entry to heaven. Muslims view heaven as a place of joy and blessings, with Quranic references describing its features. Mystical traditions in Islam place these heavenly delights in the context of an ecstatic awareness of God.[104][105][106][107] Yawm al-Qiyāmah is also identified in the Quran as Yawm ad-Dīn (يوم الدين "Day of Religion");[lower-roman 3] as-Sāʿah (الساعة "the Last Hour");[lower-roman 4] and al-Qāriʿah (القارعة "The Clatterer");[lower-roman 5]

Divine predestination

The concept of divine decree and destiny in Islam (Arabic: القضاء والقدر, al-qadāʾ wa l-qadar) means that every matter, good or bad, is believed to have been decreed by God. Al-qadar, meaning "power", derives from a root that means "to measure" or "calculating".[108][109][110][111] Muslims often express this belief in divine destiny with the phrase "Insha-Allah" meaning "if God wills" when speaking on future events.[112][113] In addition to loss, gain is also seen as a test of believers – whether they would still recognize that the gain originates only from God.[114]

Acts of worship

There are five obligatory acts of worship – the Shahada declaration of faith, the five daily prayers, the Zakat alms-giving, fasting during Ramadan and the Hajj pilgrimage – collectively known as "The Pillars of Islam" (Arkān al-Islām).[115] Apart from these, Muslims also perform other supplemental religious acts.

Testimony

The shahadah,[116] is an oath declaring belief in Islam. The expanded statement is "ʾašhadu ʾal-lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāhu wa ʾašhadu ʾanna muħammadan rasūlu-llāh" (أشهد أن لا إله إلا الله وأشهد أن محمداً رسول الله), or, "I testify that there is no deity except God and I testify that Muhammad is the messenger of God."[117] Islam is sometimes argued to have a very simple creed with the shahada being the premise for the rest of the religion. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the shahada in front of witnesses.[118][119][120]

Prayer

Prayer in Islam, called as-salah or aṣ-ṣalāt (Arabic: الصلاة), is seen as a personal communication with God and consists of repeating units called rakat that include bowing and prostrating to God. Performing prayers five times a day is compulsory. The prayers are recited in the Arabic language and consist of verses from the Quran.[121][122][123][124] The prayers are done in direction of the Ka'bah. Salah requires ritual purity, which involves wudu (ritual wash) or occasionally, such as for new converts, ghusl (full body ritual wash). The means used to signal the prayer time is a vocal call called the adhan.

A mosque is a place of worship for Muslims, who often refer to it by its Arabic name masjid. Although the primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place of prayer, it is also important to the Muslim community as a place to meet and study with the Masjid an-Nabawi ("Prophetic Mosque") in Medina, Saudi Arabia, having also served as a shelter for the poor.[125] Minarets are towers used to call the adhan.[126][127]

Charity

Zakāt (Arabic: زكاة, zakāh) is a means of welfare in a Muslim society, characterized by the giving of a fixed portion (2.5% annually)[128] of accumulated wealth by those who can afford it to help the poor or needy, such as for freeing captives, those in debt, or for (stranded) travellers, and for those employed to collect zakat.[129] It is considered a religious obligation that the well-off owe to the needy because their wealth is seen as a "trust from God's bounty" and is seen as a "purification" of one's excess wealth. Conservative estimates of annual zakat are that it amounts to 15 times global humanitarian aid contributions.[130] Sadaqah, as opposed to Zakat, is a much encouraged supererogatory charity.[131][132] A waqf is a perpetual charitable trust, which financed hospitals and schools in Muslim societies.[133]

Fasting

During the month of Ramadan, it is obligatory for Muslims to fast. The Ramadan fast (Arabic: صوم, ṣawm) precludes food and drink, as well as other forms of consumption, such as smoking, and is performed from dawn to sunset. The fast is to encourage a feeling of nearness to God by restraining oneself for God's sake from what is otherwise permissible and to think of the needy. In addition, there are other days when fasting is supererogatory.

Pilgrimage

The obligatory Islamic pilgrimage, called the "ḥajj" (Arabic: حج), is to be done at least once a lifetime by every Muslim with the means to do so during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah. Rituals of the Hajj mostly imitate the story of the family of Abraham. Pilgrims spend a day and a night on the plains of Mina, then a day praying and worshipping in the plain of Mount Arafat, then spending a night on the plain of Muzdalifah; then moving to Jamarat, symbolically stoning the Devil,[134] then going to the city of Mecca and walking seven times around the Kaaba, which Muslims believe Abraham built as a place of worship, then walking seven times between Mount Safa and Mount Marwah recounting the steps of Abraham's wife, Hagar, while she was looking for water for her baby Ishmael in the desert before Mecca developed into a settlement.[135][136][137] All Muslim men should wear only two simple white unstitched pieces of cloth called ihram, intended to bring continuity through generations and uniformity among pilgrims despite class or origin.[138][139] Another form of pilgrimage, umrah, is supererogatory and can be undertaken at any time of the year. Medina is also a site of Islamic pilgrimage and Jerusalem, the city of many Islamic prophets, contains the Al-Aqsa Mosque, which used to be the direction of prayer before Mecca.

Quranic recitation and memorization

Muslims recite and memorize the whole or parts of the Quran as acts of virtue. Reciting the Quran with elocution (tajwid) has been described as an excellent act of worship.[140] Pious Muslims recite the whole Quran during the month of Ramadan.[141] In Muslim societies, any social program generally begins with the recitation of the Quran.[141] One who has memorized the whole Quran is called a hafiz ("memorizer") who, it is said, will be able to intercede for ten people on the Last Judgment Day.[140] Apart from this, almost every Muslim memorizes some portion of the Quran because they need to recite it during their prayers.

Supplication and remembrance

Supplication to God, called in Arabic ad-duʿāʾ (Arabic: الدعاء IPA: [duˈʕæːʔ]) has its own etiquette such as raising hands as if begging or invoking with an extended index finger.

Remebrance of God (ذكر, Dhikr') refers to phrases repeated referencing God. Commonly, this includes Tahmid, declaring praise be due to God (الحمد لله, al-Ḥamdu lillāh) during prayer or when feeling thankful, Tasbih, declaring glory to God during prayer or when in awe of something and saying 'in the name of God' (بسملة, basmalah) before starting an act such as eating.

History

Muhammad (610–632)

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

.png.webp) |

|

Born in Mecca in 571, Muhammad was orphaned early in life. New trade routes rapidly transformed Meccan society from a semi-bedouin society to a commercial urban society, leaving out weaker segments of society without protection. He acquired the nickname "trustworthy" (Arabic: الامين), [142] and was sought after as a bank to safeguard valuables and an impartial arbitrator. Affected by the ills of society and after becoming financially secure through marrying his employer, the businesswoman Khadija, he began retreating to a cave to contemplate. During the last 22 years of his life, beginning at age 40 in 610 CE, Muhammad reported receiving revelations from God, conveyed to him through the archangel Gabriel,[143][144][145] thus becoming the seal of the prophets sent to the mankind according to Islamic tradition.[146][77][78][147][143]

During this time, while in Mecca, Muhammad preached first in secret and then in public, imploring his listeners to abandon polytheism and worship one God. Many early converts to Islam were women, the poor, foreigners, and slaves like the first muezzin Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi. The Meccan elite profited from the pilgrimages to the idols of the Kaaba and felt Muhammad was destabilizing their social order by preaching about one God, and that in the process he gave questionable ideas to the poor and slaves.[148][149][150][151] Muhammad, who was accused of being a poet, a madman or possessed, presented the challenge of the Quran to imitate the like of the Quran in order to disprove him. The Meccan authorities persecuted Muhammad and his followers, including a boycott and banishment of Muhammad and his clan to starve them into withdrawing their protection of him. This resulted in the Migration to Abyssinia of some Muslims (to the Aksumite Empire).

After 12 years of the persecution of Muslims by the Meccans, Muhammad and his companions performed the Hijra ("emigration") in 622 to the city of Yathrib (current-day Medina). There, with the Medinan converts (the Ansar) and the Meccan migrants (the Muhajirun), Muhammad in Medina established his political and religious authority. The Constitution of Medina was signed[lower-alpha 2] by all the tribes of Medina agreeing to defend Medina from external threats and establishing among the Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and pagan communities religious freedoms and freedom to use their own laws, security of women and the role of Medina as a sacred place barred of weapons and violence.[157] Within a few years, two battles took place against the Meccan forces: first, the Battle of Badr in 624—a Muslim victory—and then a year later, when the Meccans returned to Medina, the Battle of Uhud, which ended inconclusively.[158] The Arab tribes in the rest of Arabia then formed a confederation, and during the Battle of the Trench (March–April 627) besieged Medina, intent on finishing off Islam. In 628, the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was signed between Mecca and the Muslims, but it was broken by Mecca two years later. After signing the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, many more people converted to Islam. At the same time, Meccan trade routes were cut off as Muhammad brought surrounding desert tribes under his control.[159][160] By 629 Muhammad was victorious in the nearly bloodless conquest of Mecca, and by the time of his death in 632 (at age 62) he had united the tribes of Arabia into a single religious polity.[161]

The earliest three generations of Muslims are known as the Salaf, with the companions of Muhammad being known as the Sahaba. Many of them, such as the largest narrator of hadith Abu Hureyrah, recorded and compiled what would constitute the sunnah.

Caliphate and civil strife (632–750)

Following Muhammad's death in 632, Muslims disagreed over who would succeed him as leader. The first successors – Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman ibn al-Affan, Ali ibn Abi Talib and sometimes Hasan ibn Ali[162] – are known in Sunni Islam as al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn ("Rightly Guided Caliphs").[163] Some tribes left Islam and rebelled under leaders who declared themselves new prophets but were crushed by Abu Bakr in the Ridda wars.[164][165][166][167][168] Under Umar, the caliphate expanded rapidly as Muslims scored major victories over the Persian and Byzantine empires.[169][170] Local populations of Jews and indigenous Christians, persecuted as religious minorities and heretics and taxed heavily, often helped Muslims take over their lands from the Byzantines and Persians, resulting in exceptionally speedy conquests.[171] Uthman was elected in 644. Ali reluctantly accepted being elected the next Caliph after Uthman, whose assassination by rebels in 656 led to the First Civil War. Muhammad's widow, Aisha, raised an army against Ali, asking to avenge the death of Uthman, but was defeated at the Battle of the Camel. Ali attempted to remove the governor of Syria, Mu'awiya, who was seen as corrupt. Mu'awiya then declared war on Ali after accusing him of being behind Uthman's death. Ali defeated him in the Battle of Siffin, and then decided to arbitrate with him. This angered the Kharijites, an extremist sect, who felt Ali should do battle with Mu'awiya. They felt that by not fighting a sinner, Ali became a sinner as well. The Kharijites rebelled against Ali and were defeated in the Battle of Nahrawan but a Kharijite assassin later killed Ali. Subsequently, Ali's son, Hasan ibn Ali, was elected Caliph. To avoid further fighting, Hasan signed a peace treaty abdicating to Mu'awiyah in return for him not appointing a successor.[172] Mu'awiyah began the Umayyad dynasty with the appointment of his son Yazid I. This sparked the Second Civil War. During the Battle of Karbala, Husayn ibn Ali and other descendants of Muhammad were massacred by Yazid; the event has been annually commemorated by Shia ever since. Sunnis, led by Ibn al-Zubayr, who were opposed to the caliphate turning into a dynasty were defeated in the Siege of Mecca. These disputes over leadership would give rise to the Sunni-Shia schism,[173] with the Shia believing leadership belonging to Ali and the family of Muhammad called the ahl al-bayt.[174] Meanwhile, the Kharijites disagreed with Uthman and Ali. Quietist forms led to the emergence of the third largest denomination in Islam, Ibadiyya.

Abu Bakr's leadership oversaw the beginning of the compilation of the Qur'an. The Caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz set up the influential committee, The Seven Fuqaha of Medina,[175][176] headed by Qasim ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr.[177] Malik ibn Anas wrote one of the earliest books on Islamic jurisprudence, the Muwatta,[178] as a consensus of the opinion of those jurists.[179][180][181] The Kharijites believed there is no compromised middle ground between good and evil, and any Muslim who commits a grave sin becomes an unbeliever. The term is also used to refer to later groups such as Isis.[182] Conversely, an early sect, the Murji'ah taught that people's righteousness could be judged by God alone. Therefore, wrongdoers might be considered misguided, but not denounced as unbelievers.[183] This attitude came to prevail into mainstream Islamic beliefs.[184]

The Umayyad dynasty conquered the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Narbonnese Gaul and Sindh.[185] The Umayyads struggled with a lack of legitimacy and relied on a heavily patronized military.[186] Since the jizya tax was a tax paid by non-Muslims which exempted them from military service, the Umayyads denied recognizing the conversion of non-Arabs as it reduced revenue.[184] While the Rashidun Caliphate emphasized austerity, with Umar even requiring an inventory of each official's possessions,[187] Umayyad luxury bred dissatisfaction among the pious.[184] The Kharijites led the Berber Revolt leading to the first Muslim states independent of the Caliphate. In the Abbasid revolution, non-Arab converts (mawali), Arab clans pushed aside by the Umayyad clan, and some Shi'a rallied and overthrew the Umayyads, inaugurating the more cosmopolitan Abbasid dynasty in 750.[188][189]

Classical era (750–1258)

Al-Shafi'i codified a method to determine the reliability of hadith.[190] During the early Abbasid era, scholars such as Bukhari and Muslim compiled the major Sunni hadith collections while scholars like Al-Kulayni and Ibn Babawayh compiled major Shia hadith collections. The four Sunni Madh'habs, the Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki, and Shafi'i, were established around the teachings of Abū Ḥanīfa, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Malik ibn Anas and al-Shafi'i. In contrast, the teachings of Ja'far al-Sadiq formed the Ja'fari jurisprudence. In the 9th century Al-Tabari completed the first commentary of the Quran, that became one of the most cited commentaries in Sunni Islam, the Tafsir al-Tabari. Some Muslims began questioning the piety of indulgence in worldly life and emphasized poverty, humility, and avoidance of sin based on renunciation of bodily desires. Ascetics such as Hasan al-Basri would inspire a movement that would evolve into Tasawwuf or Sufism.[191][192]

At this time, theological problems, notably on free will, were prominently tackled, with Hasan al Basri holding that although God knows people's actions, good and evil come from abuse of free will and the devil.[193][lower-alpha 3] Greek rationalist philosophy influenced a speculative school of thought known as Muʿtazila, first originated by Wasil ibn Ata.[195] Caliphs such as Mamun al Rashid and Al-Mu'tasim made it an official creed and unsuccessfully attempted to force their position on the majority.[196] They carried out inquisitions with the traditionalist Ahmad ibn Hanbal notably refusing to conform to the Mutazila idea of the creation of the Quran and was tortured and kept in an unlit prison cell for nearly thirty months.[197] However, other schools of speculative theology – Māturīdism founded by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi and Ash'ari founded by Al-Ash'ari – were more successful in being widely adopted. Philosophers such as Al-Farabi, Avicenna and Averroes sought to harmonize Aristotle's metaphysics within Islam, similar to later scholasticism within Christianity in Europe, and Maimonides' work within Judaism, while others like Al-Ghazali argued against such syncretism and ultimately prevailed.[198][199]

This era is sometimes called the "Islamic Golden Age".[200][201][202][203][170] Avicenna was a pioneer in experimental medicine,[204][205] and his The Canon of Medicine was used as a standard medicinal text in the Islamic world and Europe for centuries. Rhazes was the first to distinguish the diseases smallpox and measles.[206] Public hospitals of the time issued the first medical diplomas to license doctors.[207][208] Ibn al-Haytham is regarded as the father of the modern scientific method and often referred to as the "world's first true scientist", in particular regarding his work in optics.[209][210][211][212] In engineering, the Banū Mūsā brothers' automatic flute player is considered to have been the first programmable machine.[213] In mathematics, the concept of the algorithm is named after Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who is considered a founder of algebra, which is named after his book al-jabr,[214] while others developed the concept of a function.[215] The government paid scientists the equivalent salary of professional athletes today.[216] The Guinness World Records recognizes the University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859, as the world's oldest degree-granting university.[217]

The vast Abbasid empire proved impossible to hold together.[218] Soldiers established their own dynasties, such as the Tulunids, Samanid and Ghaznavid dynasty,[219] and the millennialist Isma'ili Shi'a missionary movement rose with the Fatimid dynasty taking control of North Africa[220] and with the Qarmatians sacking Mecca and stealing the Black Stone in their unsuccessful rebellion.[221] In what is called the Shi'a Century, another Ismaili group, the Buyid dynasty conquered Baghdad and turned the Abbasids into a figurehead monarchy. The Sunni Seljuk dynasty, campaigned to reassert Sunni Islam by promulgating the accumulated scholarly opinion of the time notably with the construction of educational institutions known as Nezamiyeh, which are associated with Al-Ghazali and Saadi Shirazi.[222] The Ismailis continued splintering over the legitimacy of successive imams with the Alawites and the Druze, offshoots of Shi'a Islam, dating to this time.

Religious missions converted Volga Bulgaria to Islam. The Delhi Sultanate reached deep into the Indian Subcontinent and many converted to Islam,[223][224] in particular low-caste Hindus whose descendents make up the vast majority of Indian Muslims.[225] Many Muslims also went to China to trade, virtually dominating the import and export industry of the Song dynasty.[226]

Pre-Modern era (1258–18th century)

Through Muslim trade networks and the activity of Sufi orders, Islam spread into new areas.[43][227] Under the Ottoman Empire, Islam spread to Southeast Europe.[228] Conversion to Islam, however, was not a sudden abandonment of old religious practices; rather, it was typically a matter of "assimilating Islamic rituals, cosmologies, and literatures into... local religious systems",[229] as illustrated by Muhammad's appearance in Hindu folklore.[230] The Turks probably found similarities between Sufi rituals and Shaman practices.[231] Muslim Turks incorporated elements of Turkish Shamanism beliefs to Islam.[lower-alpha 4][231] Muslims in China, who were descended from earlier immigrants, were assimilated, sometimes by force, by adopting Chinese names and culture while Nanjing became an important center of Islamic study.[233][234]

While cultural influence used to radiate outward from Baghdad, after the Mongol destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate, Arab influence decreased.[235] Iran and Central Asia, benefiting from increased cross-cultural access to East Asia under Mongol rule, flourished and developed more distinctively from Arab influence, such as the Timurid Renaissance under the Timurid dynasty.[236] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) proposed the mathematical model that was later adopted by Copernicus unrevised in his heliocentric model and Jamshīd al-Kāshī's estimate of pi would not be surpassed for 180 years.[237] Many Muslim dynasties in India chose Persian as their court language.

The introduction of gunpowder weapons led to the rise of large centralized states and the Muslim Gunpowder empires consolidated much of the previously splintered territories. The caliphate was claimed by the Ottoman dynasty of the Ottoman Empire since Murad I's conquest of Edirne in 1362,[238] and its claims were strengthened in 1517 as Selim I became the ruler of Mecca and Medina.[239] The Shia Safavid dynasty rose to power in 1501 and later conquered all of Iran.[240] In South Asia, Babur founded the Mughal Empire. The Mughals made major contributions to Islamic architecture, including the Taj Mahal and Badshahi mosque, and compiled the Fatwa Alamgiri.

The religion of the centralized states of the Gunpowder empires influenced the religious practice of their constituent populations. A symbiosis between Ottoman rulers and Sufism strongly influenced Islamic reign by the Ottomans from the beginning. According to Ottoman historiography, the legitimation of a ruler is attributed to Sheikh Edebali who interpreted a dream of Osman Gazi as God's legitimation of his reign.[241] The Mevlevi Order and Bektashi Order had a close relation to the sultans,[242] as Sufi-mystical as well as heterodox and syncretic approaches to Islam flourished.[243][244] The often forceful Safavid conversion of Iran to the Twelver Shia Islam of the Safavid Empire ensured the final dominance of the Twelver sect within Shia Islam. Persian migrants to South Asia, as influential bureaucrats and landholders, help spread Shia Islam, forming some of the largest Shia populations outside Iran.[245] Nader Shah, who overthrew the Safavids, attempted to improve relations with Sunnis by propagating the integration of Twelverism into Sunni Islam as a fifth madhhab, called Ja'farism,[246] which failed to gain recognition from the Ottomans.[247]

Modern era (18th – 20th centuries)

Earlier in the 14th century, Ibn Taymiyya promoted a puritanical form of Islam,[248] rejecting philosophical approaches in favor of simpler theology[248] and called to open the gates of itjihad rather than blind imitation of scholars.[218] He called for a jihad against those he deemed heretics[249] but his writings only played a marginal role during his lifetime.[250] During the 18th century in Arabia, Muhammad ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab, influenced by the works of Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn al-Qayyim, founded a movement, called Wahhabi with their self-designation as Muwahiddun, to return to what he saw as unadultered Islam.[251][252] He condemned many local Islamic customs, such as visiting the grave of Muhammad or saints, as later innovations and sinful[252] and destroyed sacred rocks and trees, Sufi shrines, the tombs of Muhammad and his companions and the tomb of Husayn at Karbala, a major Shia pilgrimage site.[253][254] He formed an alliance with the Saud family, which, by the 1920s, completed their conquest of the area that would become Saudi Arabia.[255] Ma Wanfu and Ma Debao promoted salafist movements in the nineteenth century such as Sailaifengye in China after returning from Mecca but were eventually persecuted and forced into hiding by Sufi groups.[256] Other groups sought to reform Sufism rather than reject it, with the Senusiyya and Muhammad Ahmad both waging war and establishing states in Libya and Sudan respectively.[257] In India, Shah Waliullah Dehlawi attempted a more conciliatory style against Sufism and influenced the Deobandi movement.[258] In response to the Deobandi movement, the Barelwi movement was founded as a mass movement, defending popular Sufism and reforming its practices.[259][260] The movement is famous for the celebration of Muhammad's birthday and today, is spread across the globe.[261]

The Muslim world was generally in political decline starting the 1800s, especially regarding non-Muslim European powers. Earlier, in the fifteenth century, the Reconquista succeeded in ending the Muslim presence in Iberia. By the 19th century; the British East India Company had formally annexed the Mughal dynasty in India.[262] As a response to Western Imperialism, many intellectuals sought to reform Islam.[263] Islamic modernism, initially labelled by Western scholars as Salafiyya, embraced modern values and institutions such as democracy while being scripture-oriented.[264][265] Notable forerunners include Muhammad 'Abduh and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani.[266] Abul A'la Maududi helped influence modern political Islam.[267] Similar to contemporary codification, Shariah was for the first time partially codified into law in 1869 in the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code.[268]

The Ottoman Empire disintegrated after World War I and the Caliphate was abolished in 1924[269] by the first President of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as part of his secular reforms.[270][271] Pan-Islamists attempted to unify Muslims and competed with growing nationalist forces, such as pan-Arabism. The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), consisting of Muslim-majority countries, was established in 1969 after the burning of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.[272]

Contact with industrialized nations brought Muslim populations to new areas through economic migration. Many Muslims migrated as indentured servants (mostly from India and Indonesia) to the Caribbean, forming the largest Muslim populations by percentage in the Americas.[273] Migration from Syria and Lebanon was the biggest contributor to the Muslim population in Latin America. The resulting urbanization and increase in trade in sub-Saharan Africa brought Muslims to settle in new areas and spread their faith, likely doubling its Muslim population between 1869 and 1914.[274] Muslim immigrants began arriving largely from former colonies in several Western European nations since the 1960s, many as guest workers.

Contemporary era (20th century–present)

Forerunners of Islamic modernism influenced Islamist political movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood and related parties in the Arab world,[275][276] which performed well in elections following the Arab Spring,[277] Jamaat-e-Islami in South Asia and the AK Party, which has democratically been in power in Turkey for decades. In Iran, revolution replaced a secular monarchy with an Islamic state. Others such as Sayyid Rashid Rida broke away from Islamic modernists[278] and pushed against embracing what he saw as Western influence.[279] While some were quietist, others believed in violence against those opposing them even other Muslims, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, who would even attempt to recreate the modern gold dinar as their monetary system.[280]

In opposition to Islamic political movements, in 20th century Turkey, the military carried out coups to oust Islamist governments, and headscarves were legally restricted, as also happened in Tunisia.[281][282] In other places religious power was co-opted, such as in Saudi Arabia, where the state monopolized religious scholarship and are often seen as puppets of the state[283] while Egypt nationalized Al-Azhar University, previously an independent voice checking state power.[284] Salafism was funded for its quietism.[285] Saudi Arabia campaigned against revolutionary Islamist movements in the Middle East, in opposition to Iran,[286] Turkey[287] and Qatar.

Muslim minorities of various ethnicities have been persecuted as a religious group.[288] This has been undertaken by communist forces like the Khmer Rouge, who viewed them as their primary enemy to be exterminated since they stood out and worshiped their own god[289] and the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang[290] and by nationalist forces such as during the Bosnian genocide.

The globalization of communication has increased dissemination of religious information. The adoption of the hijab has grown more common[291] and some Muslim intellectuals are increasingly striving to separate scriptural Islamic beliefs from cultural traditions.[292] Among other groups, this access to information has led to the rise of popular "televangelist" preachers, such as Amr Khaled, who compete with the traditional ulema in their reach and have decentralized religious authority.[293][294] More "individualized" interpretations of Islam[295] notably include Liberal Muslims who attempt to reconcile religious traditions with current secular governance[296] and women's issues.[297]

Demographics

A 2020 demographic study reported that 23.4% of the global population, or 1-1.8 billion people, are Muslims.[299][6][300] In 1900, this estimate was 12.3%,[301] in 1990 it was 19.9%[38] and projections suggest the proportion will be 29.7% by 2050.[302] It has been estimated that 87–90% of Muslims are Sunni and 10–13% are Shia,[32] with a minority belonging to other sects. Approximately 49 countries are Muslim-majority,[303][304] with 62% of the world's Muslims living in Asia, and 683 million adherents in Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh alone.[305][306] Most estimates indicate China has approximately 20 to 30 million Muslims (1.5% to 2% of the population).[307][308] Islam in Europe is the second largest religion after Christianity in many countries, with growth rates due primarily to immigration and higher birth rates of Muslims in 2005.[309] Religious conversion has no net impact on the Muslim population growth as "the number of people who become Muslims through conversion seems to be roughly equal to the number of Muslims who leave the faith".[310] It is estimated that, by 2050, the number of Muslims will nearly equal the number of Christians around the world, "due to the young age and high fertility-rate of Muslims relative to other religious groups".[302]

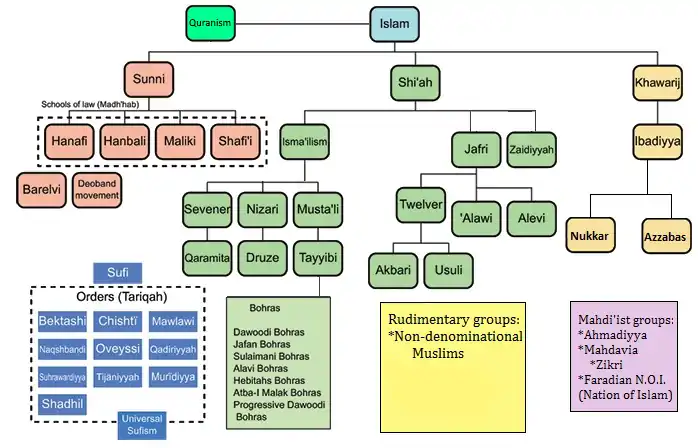

Schools and branches

Sunni

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Sunni Islam or Sunnism is the name for the largest denomination in Islam.[311] The term is a contraction of the phrase "ahl as-sunna wa'l-jamaat", which means "people of the sunna (the traditions of the prophet Muhammad) and the community".[312] Sunnis, or sometimes Sunnites, believe that the first four caliphs were the rightful successors to Muhammad and primarily reference six major hadith works for legal matters, while following one of the four traditional schools of jurisprudence: Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki or Shafi'i.[22][313]

Sunni schools of theology encompass Asharism founded by Al-Ashʿarī (c. 874–936), Maturidi by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (853–944 CE) and traditionalist theology under the leadership of Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780–855 CE). Traditionalist theology is characterized by its adherence to a literal understanding of the Quran and the Sunnah, the belief in the Quran is uncreated and eternal, and opposition to reason (kalam) in religious and ethical matters.[314] On the other hand, Maturidism asserts, scripture is not needed for basic ethics and that good and evil can be understood by reason alone,[315] but people rely on revelation, for matters beyond human's comprehension. Asharism holds that ethics can derive just from divine revelation but not from human reason. However, Asharism accepts reason regarding exegetical matters and combines Muʿtazila approaches with traditionalist ideas.[316]

In the 18th century, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab led a Salafi movement, referred by outsiders as Wahhabism, in modern-day Saudi Arabia.[317] A similar movement called Ahl al-Hadith also de-emphasized the centuries' old Sunni legal tradition, preferring to directly follow the Quran and Hadith. The Nurcu Sunni movement was by Said Nursi (1877–1960);[318] it incorporates elements of Sufism and science,[318][319] and has given rise to the Gülen movement.

Shia

Shia Islam, or Shi'ism, is the second-largest Muslim denomination. Shias, or Shiites, split with Sunnis over Muhammad's successor as leader, who the Shia believed must be from certain descendants of Muhammad's family known as the Ahl al-Bayt and those leaders, referred to as Imams, have additional spiritual authority.[320] Some of the first Imams are revered by all Shia groups and Sunnis, such as Ali. Zaidi, the oldest branch, reject special powers of Imams and are sometimes considered a 'fifth school' of Sunni Islam rather than a Shia denomination.[321][322][323] The Twelvers, the largest Shia branch, believe in twelve Imams, the last of whom went into occultation to return one day. The Ismailis split with the Twelvers over who was the seventh Imam and have split into more groups over the status of successive Imams, with the largest group being the Nizaris.[324]

Ibadi

Ibadi Islam or Ibadism is practised by 1.45 million Muslims around the world (~ 0.08% of all Muslims), most of them in Oman.[325] Ibadism is often associated with and viewed as a moderate variation of the Khawarij movement, though Ibadis themselves object to this classification. Unlike most Kharijite groups, Ibadism does not regard sinful Muslims as unbelievers. Ibadi hadiths, such as the Jami Sahih collection, uses chains of narrators from early Islamic history they considered trustworthy but most Ibadi hadiths are also found in standard Sunni collections and contemporary Ibadis often approve of the standard Sunni collections.[326]

Quranism

The Quranists are Muslims who generally believe that Islamic law and guidance should only be based on the Qur'an, rejecting the Sunnah, thus partially or completely doubting the religious authority, reliability or authenticity of the Hadith literature, which they claim are fabricated.[327]

There were first critics of the hadith traditions as early as the time of the scholar Al-Shafi'i; however, their arguments did not find much favor among Muslims. From the 19th century onwards, reformist thinkers like Sayyid Ahmad Khan, Abdullah Chakralawi, and later Ghulam Ahmad Parwez in India began to systematically question the hadith and the Islamic tradition.[328] At the same time, there was a long-standing discussion on the sole authority of the Quran in Egypt, initiated by an article by Muhammad Tawfiq Sidqi named "Islam is the Quran alone" (al-Islām huwa l-Qurʾān waḥda-hū) in the magazine al-Manār.[329][330] Quranism also took on a political dimension in the 20th century when Muammar al-Gaddafi declared the Quran to be the constitution of Libya.[331] In America, Rashad Khalifa, an Egyptian-American biochemist and discoverer of the Quran code (Code 19), which is a hypothetical mathematical code in the Quran, founded the organization "United Submitters International".[332]

The rejection of the hadith leads in some cases to differences in the way religion is practiced for example in the ritual prayer. While some Quranists traditionally pray five times a day, others reduce the number to three or even two daily prayers. There are also different views on the details of prayer or other pillars of Islam such as zakāt, fasting, or the Hajj.[333]

Other denominations

- Bektashi Alevism is a syncretic and heterodox local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical (bāṭenī) teachings of Ali and Haji Bektash Veli.[334] Alevism incorporates Turkish beliefs present during the 14th century,[335] such as Shamanism and Animism, mixed with Shias and Sufi beliefs, adopted by some Turkish tribes. It has been estimated that there are 10 million to over 20 million (~0.5%–1% of all Muslims) Alevis worldwide.[336]

- The Ahmadiyya movement was founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad[337] in India in 1889.[338][lower-alpha 5] Ahmad claimed to be the "Promised Messiah" or "Imam Mahdi" of prophecy. Today the group has 10 to 20 million practitioners, but is rejected by most Muslims as heretical,[339] and Ahmadis have been subject to religious persecution and discrimination since the movement's inception.[340]

Non-denominational Muslims

Non-denominational Muslims is an umbrella term that has been used for and by Muslims who do not belong to or do not self-identify with a specific Islamic denomination.[341][342][343] Recent surveys report that large proportions of Muslims in some parts of the world self-identify as "just Muslim", although there is little published analysis available regarding the motivations underlying this response.[344][345][346] The Pew Research Center reports that respondents self-identifying as "just Muslim" make up a majority of Muslims in seven countries (and a plurality in three others), with the highest proportion in Kazakhstan at 74%. At least one in five Muslims in at least 22 countries self-identify in this way.[347]

Mysticism

Sufism (Arabic: تصوف, tasawwuf), is a mystical-ascetic approach to Islam that seeks to find a direct personal experience of God. Classical Sufi scholars defined Tasawwuf as "a science whose objective is the reparation of the heart and turning it away from all else but God", through "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.[348][349][350][351][352][353] It is not a sect of Islam and its adherents belong to the various Muslim denominations. Ismaili Shias, whose teachings root in Gnosticism and Neoplatonism,[354] as well as by the Illuminationist and Isfahan schools of Islamic philosophy have developed mystical interpretations of Islam.[355] Hasan al-Basri, the early Sufi ascetic often portrayed as one of the earliest Sufis,[356] emphasized fear of failing God's expectations of obedience. In contrast, later prominent Sufis, such as Mansur Al-Hallaj and Jalaluddin Rumi, emphasized religiosity based on love towards God. Such devotion would also have an impact on the arts, with Rumi, still one of the best selling poets in America,[357][358] writing his Persian poem Masnawi and the works of Hafez (1315–1390) are often considered the pinnacle of Persian poetry.

Sufis reject materialism and ego[359] and regard everything as if it was sent by god alone, Sufi strongly believes in the oneness of god.[360]

Sufis see tasawwuf as an inseparable part of Islam, just like the sharia.[361] Traditional Sufis, such as Bayazid Bastami, Jalaluddin Rumi, Haji Bektash Veli, Junaid Baghdadi, and Al-Ghazali, argued for Sufism as being based upon the tenets of Islam and the teachings of the prophet.[362][361] Historian Nile Green argued that Islam in the Medieval period, was more or less Sufism.[232](p77)(p24) Popular devotional practices such as the veneration of Sufi saints have been viewed as innovations from the original religion from followers of salafism, who have sometimes physically attacked Sufis, leading to a deterioration in Sufi–Salafi relations.

Sufi congregations form orders (tariqa) centered around a teacher (wali) who traces a spiritual chain back to Muhammad.[363] Sufis played an important role in the formation of Muslim societies through their missionary and educational activities.[191] Sufi influenced Ahle Sunnat movement or Barelvi movement defends Sufi practices and beliefs with over 200 million followers in south Asia.[364][365][366] Sufism is prominent in Central Asia,[367][368] as well as in African countries like Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, Chad and Niger.[347][369]

Law and jurisprudence

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

Sharia is the religious law forming part of the Islamic tradition.[22] It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Quran and the Hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's divine law and is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its scholarly interpretations.[370][371] The manner of its application in modern times has been a subject of dispute between Muslim traditionalists and reformists.[22]

Traditional theory of Islamic jurisprudence recognizes four sources of sharia: the Quran, sunnah (Hadith and Sira), qiyas (analogical reasoning), and ijma (juridical consensus).[372] Different legal schools developed methodologies for deriving sharia rulings from scriptural sources using a process known as ijtihad.[370] Traditional jurisprudence distinguishes two principal branches of law,ʿibādāt (rituals) and muʿāmalāt (social relations), which together comprise a wide range of topics.[370] Its rulings assign actions to one of five categories called ahkam: mandatory (fard), recommended (mustahabb), permitted (mubah), abhorred (makruh), and prohibited (haram).[370][371] Forgiveness is much celebrated in Islam[373] and, in criminal law, while imposing a penalty on an offender in proportion to their offense is considered permissible; forgiving the offender is better. To go one step further by offering a favor to the offender is regarded as the peak of excellence.[374] Some areas of sharia overlap with the Western notion of law while others correspond more broadly to living life in accordance with God's will.[371]

Historically, sharia was interpreted by independent jurists (muftis). Their legal opinions (fatwa) were taken into account by ruler-appointed judges who presided over qāḍī's courts, and by maẓālim courts, which were controlled by the ruler's council and administered criminal law.[370][371] In the modern era, sharia-based criminal laws were widely replaced by statutes inspired by European models.[371] The Ottoman Empire's 19th-century Tanzimat reforms lead to the Mecelle civil code and represented the first attempt to codify sharia.[375] While the constitutions of most Muslim-majority states contain references to sharia, its classical rules were largely retained only in personal status (family) laws.[371] Legislative bodies which codified these laws sought to modernize them without abandoning their foundations in traditional jurisprudence.[371][376] The Islamic revival of the late 20th century brought along calls by Islamist movements for complete implementation of sharia.[371][376] The role of sharia has become a contested topic around the world. There are ongoing debates whether sharia is compatible with secular forms of government, human rights, freedom of thought, and women's rights.[377][378]

Schools of jurisprudence

A school of jurisprudence is referred to as a madhhab (Arabic: مذهب). The four major Sunni schools are the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanbali madhahs while the three major Shia schools are the Ja'fari, Zaidi and Isma'ili madhahib. Each differs in their methodology, called Usul al-fiqh ("principles of jurisprudence"). The following of decisions by a religious expert without necessarily examining the decision's reasoning is called taqlid. The term ghair muqallid literally refers to those who do not use taqlid and, by extension, do not have a madhab.[379] The practice of an individual interpreting law with independent reasoning is called ijtihad.[380]

Society

Religious personages

.jpg.webp)

Islam, like Judaism, has no clergy in the sacerdotal sense, such as priests who mediate between God and people. Imam (إمام) is the religious title used to refer to an Islamic leadership position, often in the context of conducting an Islamic worship service.

Religious interpretation is presided over by the ‘ulama (Arabic: علماء), a term used describe the body of Muslim scholars who have received training in Islamic studies. A scholar of the hadith is called a muhaddith, a scholar of jurisprudence is called a faqih (فقيه), a jurist who is qualified to issue legal opinions or fatwas is called a mufti, and a qadi is an Islamic judge. Honorific titles given to scholars include sheikh, mullah and mawlawi.

Some Muslims also venerate saints associated with miracles (كرامات, karāmāt). The practice of visiting the tombs of prophets and saints is known as ziyarat. Unlike saints in Christianity, Muslim saints are usually acknowledged informally by the consensus of common people, not by scholars.

Governance

Mainstream Islamic law does not distinguish between "matters of church" and "matters of state"; the scholars function as both jurists and theologians. Various forms of Islamic jurisprudence therefore rule on matters than in other societal context might be considered the preserve of the state. Terms traditionally used to refer to Muslim leaders include Caliph and Sultan, and terms associated with traditionally Muslim states include Caliphate, Emirate, Imamate and Khanate (e.g. the United Arab Emirates).

In Islamic economic jurisprudence, hoarding of wealth is reviled and thus monopolistic behavior is frowned upon.[381] Attempts to comply with shariah has led to the development of Islamic banking. Islam prohibits riba, usually translated as usury, which refers to any unfair gain in trade and is most commonly used to mean interest.[382] Instead, Islamic banks go into partnership with the borrower and both share from the profits and any losses from the venture. Another feature is the avoidance of uncertainty, which is seen as gambling[383] and Islamic banks traditionally avoid derivative instruments such as futures or options which substantially protected them from the 2008 financial crisis.[384] The state used to be involved in distribution of charity from the treasury, known as Bayt al-mal, before it became a largely individual pursuit. The first Caliph, Abu Bakr, distributed zakat as one of the first examples of a guaranteed minimum income, with each man, woman and child getting 10 to 20 dirhams annually.[385] During the reign of the second Caliph Umar, child support was introduced and the old and disabled were entitled to stipends,[386][387][388] while the Umayyad Caliph Umar II assigned a servant for each blind person and for every two chronically ill persons.[389]

Jihad means "to strive or struggle [in the way of God]" and, in its broadest sense, is "exerting one's utmost power, efforts, endeavors, or ability in contending with an object of disapprobation".[390] This could refer to one's striving to attain religious and moral perfection[391][392][393] with the Shia and Sufis in particular, distinguishing between the "greater jihad", which pertains to spiritual self-perfection, and the "lesser jihad", defined as warfare.[394][395] When used without a qualifier, jihad is often understood in its military form.[390][391] Jihad is the only form of warfare permissible in Islamic law and may be declared against illegal works, terrorists, criminal groups, rebels, apostates, and leaders or states who oppress Muslims.[394][395] Most Muslims today interpret Jihad as only a defensive form of warfare.[396] Jihad only becomes an individual duty for those vested with authority. For the rest of the populace, this happens only in the case of a general mobilization.[395] For most Twelver Shias, offensive jihad can only be declared by a divinely appointed leader of the Muslim community, and as such, is suspended since Muhammad al-Mahdi's occultation is 868 CE.[397][398]

Daily and family life

.jpg.webp)

Many daily practices fall in the category of adab, or etiquette and this includes greeting others with "as-salamu 'alaykum" ("peace be unto you"), saying bismillah ("in the name of God") before meals, and using only the right hand for eating and drinking.

Specific prohibited foods include pork products, blood and carrion. Health is viewed as a trust from God and intoxicants, such as alcoholic drinks, are prohibited.[399] All meat must come from a herbivorous animal slaughtered in the name of God by a Muslim, Jew, or Christian, except for game that one has hunted or fished for themself.[400][401][402] Beards are often encouraged among men as something natural[403][404] and body modifications, such as permanent tattoos, are usually forbidden as violating the creation.[lower-alpha 6][406] Gold and silk for men are prohibited and are seen as extravagant.[407] Haya, often translated as "shame" or "modesty", is sometimes described as the innate character of Islam[408] and informs much of Muslim daily life. For example, clothing in Islam emphasizes a standard of modesty, which has included the hijab for women. Similarly, personal hygiene is encouraged with certain requirements.

In Islamic marriage, the groom is required to pay a bridal gift (mahr).[409][410][411] Most families in the Islamic world are monogamous.[412][413] However, Muslim men are allowed to practice polygyny and can have up to four wives at the same time. There are also cultural variations in weddings.[414] Polyandry, a practice wherein a woman takes on two or more husbands, is prohibited in Islam.[415]

After the birth of a child, the Adhan is pronounced in the right ear.[416] On the seventh day, the aqiqah ceremony is performed, in which an animal is sacrificed and its meat is distributed among the poor.[417] The child's head is shaved, and an amount of money equaling the weight of its hair is donated to the poor.[417] Male circumcision is practised. Respecting and obeying one's parents, and taking care of them especially in their old age is a religious obligation.[418][419]

A dying Muslim is encouraged to pronounce the Shahada as their last words. Paying respects to the dead and attending funerals in the community are considered among the virtuous acts. In Islamic burial rituals, burial is encouraged as soon as possible, usually within 24 hours. The body is washed, except for martyrs, by members of the same gender and enshrouded in a garment that must not be elaborate called kafan.[420] A "funeral prayer" called Salat al-Janazah is performed. Wailing, or loud, mournful outcrying, is discouraged. Coffins are often not preferred and graves are often unmarked, even for kings.[421] Regarding inheritance, a son's share is double that of a daughter's.[lower-roman 6]

Arts and culture

The term "Islamic culture" can be used to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress code. It is also controversially used to denote the cultural aspects of traditionally Muslim people.[422] Finally, "Islamic civilization" may also refer to the aspects of the synthesized culture of the early Caliphates, including that of non-Muslims,[423] sometimes referred to as "Islamicate".

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts including fields as varied as architecture, calligraphy, painting, and ceramics, among others.[424] While the making of images of animate beings has often been frowned upon in connection with laws against idolatry, this rule has been interpreted in different ways by different scholars and in different historical periods. This stricture has been used to explain the prevalence of calligraphy, tessellation, and pattern as key aspects of Islamic artistic culture.[425] In Islamic architecture, varying cultures show influence such as North African and Spanish Islamic architecture such as the Great Mosque of Kairouan containing marble and porphyry columns from Roman and Byzantine buildings,[426] while mosques in Indonesia often have multi-tiered roofs from local Javanese styles.

The Islamic calendar is a lunar calendar that begins with the Hijra of 622 CE, a date that was reportedly chosen by Caliph Umar as it was an important turning point in Muhammad's fortunes.[427] Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, meaning they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar. The most important Islamic festivals are Eid al-Fitr (Arabic: عيد الف) on the 1st of Shawwal, marking the end of the fasting month Ramadan, and Eid al-Adha (عيد الأضحى) on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijjah, coinciding with the end of the Hajj (pilgrimage).[428]

Great Mosque of Djenné, in the west African country of Mali

Great Mosque of Djenné, in the west African country of Mali Dome in Po-i-Kalyan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Dome in Po-i-Kalyan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan 14th century Great Mosque of Xi'an in China

14th century Great Mosque of Xi'an in China 16th century Menara Kudus Mosque in Indonesia showing Indian influence

16th century Menara Kudus Mosque in Indonesia showing Indian influence The phrase Bismillah in an 18th-century Islamic calligraphy from the Ottoman region.

The phrase Bismillah in an 18th-century Islamic calligraphy from the Ottoman region.

Derived religions

Some movements, such as the Druze,[429][430][431][432][433] Berghouata and Ha-Mim, either emerged from Islam or came to share certain beliefs with Islam, and whether each is a separate religion or a sect of Islam is sometimes controversial. Yazdânism is seen as a blend of local Kurdish beliefs and Islamic Sufi doctrine introduced to Kurdistan by Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir in the 12th century. Bábism stems from Twelver Shia passed through Siyyid 'Ali Muhammad i-Shirazi al-Bab while one of his followers Mirza Husayn 'Ali Nuri Baha'u'llah founded the Baháʼí Faith.[434] Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak in late-fifteenth-century Punjab, primarily incorporates aspects of Hinduism, with some Islamic influences.[435]

Criticism

Criticism of Islam has existed since Islam's formative stages. Early criticism came from Christian authors, many of whom viewed Islam as a Christian heresy or a form of idolatry, often explaining it in apocalyptic terms.[437] Later, criticism from the Muslim world itself appeared, as well as from Jewish writers and from ecclesiastical Christians.[438][439]

Christian writers criticized Islamic salvation optimism and its carnality. Islam's sensual descriptions of paradise led many Christians to conclude that Islam was not a spiritual religion. Although sensual pleasure was also present in early Christianity, as seen in the writings of Irenaeus, the doctrines of the former Manichaean, Augustine of Hippo, led to the broad repudiation of bodily pleasure in both life and the afterlife. Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari defended the Quranic description of paradise by asserting that the Bible also implies such ideas, such as drinking wine in the Gospel of Matthew.[440]

Defamatory images of Muhammad, derived from early 7th century depictions of the Byzantine Church,[441] appear in the 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri.[442] Here, Muhammad appears in the eighth circle of hell, along with Ali. Dante does not blame Islam as a whole but accuses Muhammad of schism, by establishing another religion after Christianity.[442]

Other criticisms focus on the question of human rights in modern Muslim-majority countries, and the treatment of women in Islamic law and practice.[443] In the wake of the recent multiculturalism trend, Islam's influence on the ability of Muslim immigrants in the West to assimilate has been criticized.[444] Both in his public and personal life, others objected to the morality of Muhammad, therefore also the sunnah as a role model.[445]

See also

- Glossary of Islam

- Index of Islam-related articles

- Islamic mythology

- Islamic studies

- Major religious groups

- Outline of Islam

References

Footnotes

- There are ten pronunciations of Islam in English, differing in whether the first or second syllable has the stress, whether the s is /z/ or /s/, and whether the a is pronounced /ɑː/, /æ/ or (when the stress is on the first syllable) /ə/ (Merriam Webster). The most common are /ɪzˈlɑːm, ɪsˈlɑːm, ˈɪzləm, ˈɪsləm/ (Oxford English Dictionary) and /ˈɪzlɑːm, ˈɪslɑːm/ (American Heritage Dictionary).

- Watt argues that the initial agreement came about shortly after the hijra and that the document was amended at a later date—specifically after the battle of Badr (AH [anno hijra] 2, = AD 624).[152] Serjeant argues that the constitution is, in fact, eight different treaties that can be dated according to events as they transpired in Medina, with the first treaty written shortly after Muhammad's arrival.[153] See also Caetani (1905) who argue that the document is a single treaty agreed upon shortly after the hijra.[154] Wellhausen argues that it belongs to the first year of Muhammad's residence in Medina, before the battle of Badr in 2/624.[155] Even Moshe Gil, a sceptic of Islamic history, argues that it was written within five months of Muhammad's arrival in Medina.[156]

- "Hasan al Basri is often considered one of the first who rejected an angelic origin for the devil, arguing that his fall was the result of his own free-will, not God's determination. Hasan al Basri also argued that angels are incapable of sin or errors and nobler than humans and even prophets. Both early Shias and Sunnis opposed his view.[194]

- "In recent years, the idea of syncretism has been challenged. Given the lack of authority to define or enforce an Orthodox doctrine about Islam, some scholars argue there had no prescribed beliefs, only prescribed practise, in Islam before the sixtheenth century.[232](p20–22)

- A figure of 10-20 million represents approximately 1% of the Muslim population. See also: Ahmadiyya by country.

- Some Muslims in dynastic era China resisted footbinding of girls for the same reason.[405]

Qur'an and hadith

Citations

- Hamzeh'ee, M. Reza Fariborz (1995). Krisztina Kehl-Bodrogi; et al. (eds.). Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East. Leiden: Brill. pp. 101–117. ISBN 90-04-10861-0.

- Browne, Edward G. (1889). Bábism.

- "World's Baha'i connect with past in Israel". Reuters. 20 January 2007 – via www.reuters.com.

- Hunter, Shireen (2010). The Politics of Islamic Revivalism: Diversity and Unity: Center for Strategic and International Studies (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown University. Center for Strategic and International Studies. University of Michigan Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780253345493.

Druze - An offshoot of Shi'ism; its members are not considered Muslims by orthodox Muslims.

- Yazbeck Haddad, Yvonne (2014). The Oxford Handbook of American Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780199862634.

While they appear parallel to those of normative Islam, in the Druze religion they are different in meaning and interpretation. The religion is consider distinct from the Ismaili as well as from other Muslims belief and practice... Most Druze do not identify as Muslims...

- "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". 7 October 2009.

- "Islam | Religion, Beliefs, Practices, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Definition of Islam | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Muslim." Lexico. UK: Oxford University Press. 2020.

- Esposito, John L. 2009. "Islam." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference.) "Profession of Faith...affirms Islam's absolute monotheism and acceptance of Muḥammad as the messenger of Allah, the last and final prophet."

- Peters, F. E. 2009. "Allāh." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, edited by J. L. Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. (See also: quick reference.) "[T]he Muslims' understanding of Allāh is based...on the Qurʿān's public witness. Allāh is Unique, the Creator, Sovereign, and Judge of mankind. It is Allāh who directs the universe through his direct action on nature and who has guided human history through his prophets, Abraham, with whom he made his covenant, Moses/Moosa, Jesus/Eesa, and Muḥammad, through all of whom he founded his chosen communities, the 'Peoples of the Book.'"

- "Muslim Population By Country 2021". World Population Review. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050". Pew Research Center. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Campo (2009), p. 34, "Allah".

- Özdemir, İbrahim. 2014. "Environment." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam, edited by I. Kalin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-981257-8. "When Meccan pagans demanded proofs, signs, or miracles for the existence of God, the Qurʾān's response was to direct their gaze at nature's complexity, regularity, and order. The early verses of the Qurʾān, therefore, reveal an invitation to examine and investigate the heavens and the earth, and everything that can be seen in the environment.... The Qurʾān thus makes it clear that everything in Creation is a miraculous sign of God (āyah), inviting human beings to contemplate the Creator."

- Goldman, Elizabeth (1995). Believers: Spiritual Leaders of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508240-1.

- Reeves, J. C. (2004). Bible and Qurʼān: Essays in scriptural intertextuality. Leiden: Brill. p. 177. ISBN 90-04-12726-7.

- "Global Connections . Religion | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- Bennett (2010), p. 101.

- Esposito, John L. (ed.). "Eschatology". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam – via Oxford Islamic Studies Online.

- Esposito (2002b), pp. 17, 111–112, 118.

- Coulson, Noel James. "Sharīʿah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 September 2021. (See also: "sharia" via Lexico.)

- Trofimov, Yaroslav. 2008. The Siege of Mecca: The 1979 Uprising at Islam's Holiest Shrine. Knopf. New York. ISBN 978-0-307-47290-8. p. 79.

- Watt, William Montgomery (2003). Islam and the Integration of Society. Psychology Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-17587-6.

- Saliba, George. 1994. A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-8023-7. pp. 245, 250, 256–57.

- King, David A. (1983). "The Astronomy of the Mamluks". Isis. 74 (4): 531–55. doi:10.1086/353360. S2CID 144315162.

- Hassan, Ahmad Y. 1996. "Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century." Pp. 351–99 in Islam and the Challenge of Modernity, edited by S. S. Al-Attas. Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Arnold, Thomas Walker. The Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith.

- Denny, Frederick. 2010. Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 3. "Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community."

- "Field Listing :: Religions". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

Sunni Islam accounts for over 75% of the world's Muslim population." ... "Shia Islam represents 10–15% of Muslims worldwide.

- "Sunni". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

Sunni Islam is the largest denomination of Islam, comprising about 85% of the world's over 1.5 billion Muslims.

- Pew Forum for Religion & Public Life (2009), p. 1. "Of the total Muslim population, 10–13% are Shia Muslims and 87–90% are Sunni Muslims."

- "Muslim Majority Countries 2021". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 25 July 2021.