Muhammad in Islam

Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib ibn Hāshim (Arabic: مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ عَبْدِ ٱللهِ بْنِ عَبْدِ ٱلْمُطَّلِبِ بْنِ هَاشِمٍ; c. 570 – 8 June 632 CE), is believed to be the seal of the messengers and prophets of God in all the main branches of Islam. Muslims believe that the Quran, the central religious text of Islam, was revealed to Muhammad by God, and that Muhammad was sent to restore Islam, which they believe did not originate with Muhammad but is the true unaltered original monotheistic faith of Adam, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and other prophets.[1][2][3][4] The religious, social, and political tenets that Muhammad established with the Quran became the foundation of Islam and the Muslim world.[5]

Imam al-Anbiya Rasūl Allāh Muhammad | |

|---|---|

مُحَمَّدٌ | |

'Muhammad' in Islamic calligraphy | |

| Prophet of Islam | |

| Preceded by | Isa (Jesus) |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Title | Khatam an-Nabiyyin ('Seal of the Prophets') |

| Personal | |

| Born | Monday, 12 Rabi' al-Awwal 53 BH (c. 21 April 570 CE) or Saturday, 17 Rabi' al-Awwal 53 BH (c. 26 April 570 CE) |

| Died | Monday, 12 Rabi' al-Awwal 11 AH (8 June 632 CE) Medina, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Resting place | Green Dome, Prophet's Mosque, Medina |

| Religion | Islam |

| Spouse | See Muhammad's wives |

| Children | See Muhammad's children |

| Parents |

|

| Notable work(s) | Constitution of Medina |

| Other names | See Names and titles of Muhammad |

| Relatives | See Family tree of Muhammad, Ahl al-Bayt ("Family of the House") |

| Signature |  Seal of Muhammad |

| Muslim leader | |

| Successor | See Succession to Muhammad |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Muhammad |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | Muḥammad ibn Abd Allah ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim ibn Abd Manaf ibn Qusai ibn Kilab |

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | Abu al-Qasim |

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Born about the year 53 BH (570 CE) into a respected Qurayshi family of Mecca, Muhammad earned the title "al-Amin" (اَلْأَمِينُ, meaning "the Trustworthy").[6][7] At the age of 40 in 11 BH (610 CE), Muhammad is said to have received his first verbal revelation in the cave called Hira, which was the beginning of the descent of the Quran that continued up to the end of his life; and Muslims hold that Muhammad was asked by God to preach the oneness of God in order to stamp out idolatry, a practice overtly present in pre-Islamic Arabia.[8][9] Because of persecution of the newly converted Muslims, upon the invitation of a delegation from Medina (then known as Yathrib), Muhammad and his followers migrated to Medina in 1 AH (622 CE), an event known as the Hijrah.[10][11] A turning point in Muhammad's life, this Hijrah also marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. In Medina, Muhammad sketched out the Constitution of Medina specifying the rights of and relations among the various existing communities there, formed an independent community, and managed to establish the first Islamic state.[12] Despite the ongoing hostility of the Meccans, Muhammad, along with his followers, took control of Mecca in 630,[13][14] and ordered the destruction of all pagan idols.[15][16] In his later years in Medina, Muhammad unified the different tribes of Arabia under Islam[17] and carried out social and religious reforms.[18] By the time he died in about 11 AH (632 CE), almost all the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam.[19]

Muslims often refer to Muhammad as Prophet Muhammad, or just "The Prophet" or "The Messenger", and regard him as the greatest of all Prophets.[1][20][21][22] He is seen by the Muslims as a possessor of all virtues.[23] As an act of respect, Muslims follow the name of Muhammad by the Arabic benediction sallallahu 'alayhi wa sallam, (meaning Peace be upon him),[24] sometimes abbreviated as "SAW" or "PBUH".

In the Quran

The Quran enumerates little about Muhammad's early life or other biographic details, but it talks about his prophetic mission, his moral excellence, and theological issues regarding Muhammad. According to the Quran, Muhammad is the last in a chain of prophets sent by God (33:40). Throughout the Quran, Muhammad is referred to as "Messenger", "Messenger of God", and "Prophet". Some of such verses are 2:101, 2:143, 2:151, 3:32, 3:81, 3:144, 3:164, 4:79-80, 5:15, 5:41, 7:157, 8:01, 9:3, 33:40, 48:29, and 66:09. Other terms are used, including "Warner", "bearer of glad tidings", and the "one who invites people to a Single God" (Quran 12:108, and 33:45-46). The Quran asserts that Muhammad was a man who possessed the highest moral excellence, and that God made him a good example or a "goodly model" for Muslims to follow (Quran 68:4, and 33:21). The Quran disclaims any superhuman characteristics for Muhammad,[25] but describes him in terms of positive human qualities. In several verses, the Quran crystallizes Muhammad's relation to humanity. According to the Quran, God sent Muhammad with truth (God's message to humanity), and as a blessing to the whole world (Quran 39:33, and 21:107). In Islamic tradition, this means that God sent Muhammad with his message to humanity the following of which will give people salvation in the afterlife, and it is Muhammad's teachings and the purity of his personal life alone which keep alive the worship of God on this world.[26]

According to the Quran, the coming of Muhammad was predicted by Jesus: "And remember, Jesus, the son of Mary, said: ‘O children of Israel! I am God;s messenger to you, confirming the law (which came) before me, and giving glad tidings of a messenger to come after me, whose name shall be Ahmad'" (Quran 61:6). Through this verse, early Arab Muslims claimed legitimacy for their new faith in the existing religious traditions and the alleged predictions of Jesus.[27]

Traditional Muslim account

Early years

Muhammad, the son of 'Abdullah ibn 'Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim and his wife Aminah, was born in 570 CE, approximately,[28][n 1] in the city of Mecca in the Arabian Peninsula. He was a member of the family of Banu Hashim, a respected branch of the prestigious and influential Quraysh tribe. It is generally said that 'Abd al-Muttalib named the child "Muhammad" (Arabic: مُحَمَّد).[29]

Orphanhood

Muhammad was orphaned when young. Some months before the birth of Muhammad, his father died near Medina on a mercantile expedition to Syria.[30][31][32] When Muhammad was six, he accompanied his mother Amina on her visit to Medina, probably to visit her late husband's tomb. While returning to Mecca, Amina died at a desolate place called Abwa, about half-way to Mecca, and was buried there. Muhammad was now taken in by his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, who himself died when Muhammad was eight, leaving him in the care of his uncle Abu Talib. In Islamic tradition, Muhammad's being orphaned at an early age has been seen as a part of divine plan to enable him to "develop early the qualities of self-reliance, reflection, and steadfastness".[33] Muslim scholar Muhammad Ali sees the tale of Muhammad as a spiritual parallel to the life of Moses, considering many aspects of their lives to be shared.[34] The Quran said about Moses: "I cast (the garment of love) over thee from Me, so that thou might be reared under My eye. ... We saved thee from all grief, although We tried thee with various trials. ... O Moses, I have chosen thee for Mine Own service" (20:39-41). Taking into account the idea of this spiritual parallelism, together with other aspects of Muhammad's early life, it has been suggested that it was God under Whose direct care Muhammad was raised and prepared for the responsibility that was to be conferred upon him.[33] Islamic scholar Tariq Ramadan argued that Muhammad's orphan state made him dependent on God and close to the destitute – an "initiatory state for the future Messenger of God".[35]

Early life

| Lineage of several prophets according to Islamic tradition |

|---|

| Dotted lines indicate multiple generations |

According to Arab custom, after his birth, infant Muhammad was sent to Banu Sa'ad clan, a neighboring Bedouin tribe, so that he could acquire the pure speech and free manners of the desert.[36] There, Muhammad spent the first five years of his life with his foster-mother Halima. Islamic tradition holds that during this period, God sent two angels who opened his chest, took out the heart, and removed a blood-clot from it. It was then washed with Zamzam water. In Islamic tradition, this incident signifies the idea that God purified his prophet and protected him from sin.[37][38]

Islamic belief holds that God protected Muhammad from getting involved in any disrespectful and coarse practice. Even when he verged on any such activity, God intervened. Prophetic tradition narrates one such incident in which it is said on the authority of Ibn Al-Atheer that while working as herdsman at early period of his life, young Muhammad once told his fellow-shepherd to take care of his sheep so that the former could go to the town for some recreation as the other youths used to do. But on the way, his attention was diverted to a wedding party, and he sat down to listen to the sound of music only to soon fall asleep. He was awakened by the heat of the sun. Muhammad reported that he never tried such things again.[39][40][41]

Around the age of twelve, Muhammad accompanied his uncle Abu Talib in a mercantile journey to Syria, and gained experience in commercial enterprise.[42] On this journey Muhammad is said to have been recognized by a Christian monk, Bahira, who prophesied about Muhammad's future as a prophet of God.[9][43]

Around the age of twenty five, Muhammad was employed as the caretaker of the mercantile activities of Khadijah, a distinguished Qurayshi lady.

Attracted by his noble ethics, honesty and trustworthiness, she sent a marriage proposal to Muhammad through her maid-servant Meisara. As Muhammad gave his consent, the marriage was solemnized in the presence of his uncle.

Social welfare

Between 580 CE and 590 CE, Mecca experienced a bloody feud between Quraysh and Bani Hawazin that lasted for four years, before a truce was reached. After the truce, an alliance named Hilf al-Fudul (The Pact of the Virtuous)[44] was formed to check further violence and injustice; and to stand on the side of the oppressed, an oath was taken by the descendants of Hashim and the kindred families, where Muhammad was also a member.[42] In later days of his life, Muhammad is reported to have said about this pact, "I witnessed a confederacy in the house of 'Abdullah bin Jada'an. It was more appealing to me than herds of cattle. Even now in the period of Islam I would respond positively to attending such a meeting if I were invited."[45]

Islamic tradition credits Muhammad with settling a dispute peacefully, regarding setting the sacred Black Stone on the wall of Kaaba, where the clan leaders could not decide on which clan should have the honor of doing that. The Black stone was removed to facilitate the rebuilding of Kaaba because of its dilapidated condition. The disagreement grew tense, and bloodshed became likely. The clan leaders agreed to wait for the next man to come through the gate of Kaaba and ask him to choose. The 35-year-old Muhammad entered through that gate first, asked for a mantle which he spread on the ground, and placed the stone at its center. Muhammad had the clans' leaders lift a corner of it until the mantle reached the appropriate height, and then himself placed the stone on the proper place. Thus, an ensuing bloodshed was averted by the wisdom of Muhammad.[9][46][47]

Prophethood

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

.png.webp) |

|

Muslims believe that Muhammad is the last and final messenger and prophet of God who began receiving direct verbal revelations in 610 CE. The first revealed verses were the first five verses of sura Al-Alaq that the archangel Jibril brought from God to Muhammad in the cave Mount Hira.[48][49]

After his marriage with Khadijah and during his career as a merchant, although engaged in commercial activities and family affairs, Muhammad gradually became preoccupied with contemplation and reflection.[9][50] and began to withdraw periodically to a cave named Mount Hira, three miles north of Mecca.[51] According to Islamic tradition, in the year 610 CE, during one such occasion while he was in contemplation, Jibril appeared before him and said 'Recite', upon which Muhammad replied: 'I am unable to recite'. Thereupon the angel caught hold of him and embraced him heavily. This happened two more times after which the angel commanded Muhammad to recite the following verses:[48][49]

Proclaim! (or read!) in the name of thy Lord and Cherisher, Who created-

Created man, out of a (mere) clot of congealed blood:

Proclaim! And thy Lord is Most Bountiful,-

He Who taught (the use of) the pen,-

Taught man that which he knew not.— Quran, chapter 96 (Al-Alaq), verse 1-5[52]

This was the first verbal revelation. Perplexed by this new experience, Muhammad made his way to home where he was consoled by his wife Khadijah, who also took him to her Christian cousin Waraqah ibn Nawfal. Waraqah was familiar with scriptures of the Torah and Gospel. Islamic tradition holds that Waraka, upon hearing the description, testified to Muhammad's prophethood.[9][53] It is also reported by Aisha that Waraqah ibn Nawfal later told Muhammad that Muhammad's own people would turn him out, to which Muhammad inquired "Will they really drive me out?" Waraka replied in the affirmative and said "Anyone who came with something similar to what you have brought was treated with hostility; and if I should be alive till that day, then I would support you strongly."[54][55] Some Islamic scholars argue that Muhammad was foretold in the Bible.[56][57][58]

Divine revelation

In Islamic belief, revelations are God's word delivered by his chosen individuals – known as Messengers—to humanity.[59] According to Islamic scholar Muhammad Shafi Usmani, God created three media through which humans receive knowledge: men's senses, the faculty of reason, and divine revelation; and it is the third one that addresses the liturgical and eschatological issues, answers the questions regarding God's purpose behind creating humanity, and acts as a guidance for humanity in choosing the correct way.[60] In Islamic belief, the sequence of divine revelation came to an end with Muhammad.[60] Muslims believe these revelations to be the verbatim word of God, which were later collected together, and came to be known as Quran, the central religious text of Islam.[61][62][63][64]

Early preaching and teachings

During the first three years of his ministry, Muhammad preached Islam privately, mainly among his near relatives and close acquaintances. The first to believe him was his wife Khadijah, who was followed by Ali, his cousin, and Zayd ibn Harithah. Notable among the early converts were Abu Bakr, Uthman ibn Affan, Hamza ibn Abdul Muttalib, Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas, Abdullah ibn Masud, Arqam, Abu Dharr al-Ghifari, Ammar ibn Yasir and Bilal ibn Rabah. In the fourth year of his prophethood, according to Islamic belief, he was ordered by God to make public his propagation of this monotheistic faith (Quran 15:94).

Muhammad's earliest teachings were marked by his insistence on the oneness of God (Quran 112:1), the denunciation of polytheism (Quran 6:19), belief in the Last judgment and its recompense (Quran 84:1–15), and social and economic justice (Quran 89:17–20).[5] In a broader sense, Muhammad preached that he had been sent as God's messenger;[65] that God is One who is all-powerful, creator and controller of this universe (Quran 85:8–9, Quran 6:2), and merciful towards his creations (Quran 85:14);[66] that worship should be made only to God;[65] that ascribing partnership to God is a major sin (Quran 4:48); that men would be accountable, for their deeds, to God on last judgment day, and would be assigned to heaven or hell (Quran 85:10–13); and that God expects man to be generous with their wealth and not miserly (Quran 107:1–7).[66]

Opposition and persecution

Muhammad's early teachings invited vehement opposition from the wealthy and leading clans of Mecca who feared the loss not only of their ancestral paganism but also of the lucrative pilgrimage business.[67] At first, the opposition was confined to ridicule and sarcasm which proved insufficient to arrest Muhammad's faith from flourishing, and soon they resorted to active persecution.[68] These included verbal attack, ostracism, unsuccessful boycott, and physical persecution.[67][69] Biographers have presented accounts of diverse forms of persecution on the newly converted Muslims by the Quraysh. The converted slaves who had no protection were imprisoned and often exposed to scorching sun. Alarmed by mounting persecution on the newly converts, Muhammad in 615 CE directed some of his followers to migrate to neighboring Abyssinia (present day Ethiopia), a land ruled by king Aṣḥama ibn Abjar famous for his justice, and intelligence.[70] Accordingly, eleven men and four women made their flight, and were followed by more in later time.[70][71]

Back in Mecca, Muhammad was gaining new followers, including notable figures like Umar ibn Al-Khattāb. Muhammad's position was greatly strengthened by their acceptance of Islam, and the Quraysh became much perturbed. Upset by the fear of losing the leading position, and shocked by continuous condemnation of idol-worship in the Quran, the merchants and clan-leaders tried to come to an agreement with Muhammad. They offered Muhammad the prospect of higher social status and advantageous marriage proposal in exchange for forsaking his preaching. Muhammad rejected both offers, asserting his nomination as a messenger by God.[72][73][74] Unable to deal with this status quo, the Quraysh then proposed to adopt a common form of worship, which was denounced by the Quran: 'Say: O ye the disbelievers, I worship not that which ye worship, Nor will ye worship that which I worship. And I will not worship that which ye have been wont to worship, Nor will ye worship that which I worship. To you be your Way, and to me mine' (109:1).

Social boycott

Thus frustrated from all sides, the leaders of various Quraysh clans, in 617 CE, enacted a complete boycott of Banu Hashim family to mount pressure to lift its protection on Muhammad. The Hashemites were made to retire in a quarter of Abu Talib, and were cut off from outside activities.[9][75] During this period, the Hashemites suffered from various scarcities, and Muhammad's preaching confined to only the pilgrimage season.[76][77] The boycott ended after three years as it failed to serve its end. This incident was shortly followed by the death of Muhammad's uncle and protector Abu Talib and his wife Khadijah.[9][78] This has largely been attributed to the plight to which the Hashemites were exposed during the boycott.[79][80]

Last years in Mecca

The death of his uncle Abu Talib left Muhammad unprotected, and exposed him to some mischief of Quraysh, which he endured with great steadfastness. An uncle and a bitter enemy of Muhammad, Abu Lahab succeeded Abu Talib as clan chief, and soon withdrew the clan's protection from Muhammad.[81] Around this time, Muhammad visited Ta'if, a city some sixty kilometers east of Mecca, to preach Islam, but met with severe hostility from its inhabitants who pelted him with stones causing bleeding. It is said that God sent angels of the mountain to Muhammad who asked Muhammad's permission to crush the people of Ta'if in between the mountains, but Muhammad said 'No'.[82][83] At the pilgrimage season of 620, Muhammad met six men of Khazraj tribe from Yathrib (later named Medina), propounded to them the doctrines of Islam, and recited portions of Quran.[81][84] Impressed by this, the six embraced Islam,[9] and at the Pilgrimage of 621, five of them brought seven others with them. These twelve informed Muhammad of the beginning of gradual development of Islam in Medina, and took a formal pledge of allegiance at Muhammad's hand, promising to accept him as a prophet, to worship none but one God, and to renounce certain sins like theft, adultery, murder and the like. This is known as the "First Pledge of al-Aqaba".[85][86] At their request, Muhammad sent with them Mus‘ab ibn 'Umair to teach them the instructions of Islam. Biographers have recorded the success of Mus'ab ibn 'Umair in preaching the message of Islam and bringing people under the umbrella of Islam in Medina.[87][88]

The next year, at the pilgrimage of June 622, a delegation of around 75 converted Muslims of Aws and Khazraj tribes from Yathrib came. They invited him to come to Medina as an arbitrator to reconcile the hostile tribes.[10] This is known as the "Second Pledge of al-'Aqabah",[85][89] and was a 'politico-religious' success that paved the way for his and his followers' emigration to Medina.[90] Following the pledges, Muhammad ordered his followers to migrate to Yathrib in small groups, and within a short period, most of the Muslims of Mecca migrated there.[91]

Emigration to Medina

Because of assassination attempts from the Quraysh, and prospect of success in Yathrib, a city 320 km (200 mi) north of Mecca, Muhammad emigrated there in 622 CE.[92] According to Muslim tradition, after receiving divine direction to depart Mecca, Muhammad began taking preparation and informed Abu Bakr of his plan. On the night of his departure, Muhammad's house was besieged by men of the Quraysh who planned to kill him in the morning. At the time, Muhammad possessed various properties of the Quraysh given to him in trust; so he handed them over to 'Ali and directed him to return them to their owners. It is said that when Muhammad emerged from his house, he recited the ninth verse of surah Ya Sin of the Quran and threw a handful of dust at the direction of the besiegers, rendering the besiegers unable to see him.[93][94] After eight days' journey, Muhammad entered the outskirts of Medina on 28 June 622,[95] but did not enter the city directly. He stopped at a place called Quba', a place some miles from the main city, and established a mosque there. On 2 July 622, he entered the city.[95] Yathrib was soon renamed Madinat an-Nabi (Arabic: مَدينة النّبي, literally "City of the Prophet"), but an-Nabi was soon dropped, so its name is "Medina", meaning "the city".[96]

In Medina

In Medina, Muhammad's first focus was on the construction of a mosque, which, when completed, was of an austere nature.[97] Apart from being the center of prayer service, the mosque also served as a headquarters of administrative activities. Adjacent to the mosque was built the quarters for Muhammad's family. As there was no definite arrangement for calling people to prayer, Bilal ibn Ribah was appointed to call people in a loud voice at each prayer time, a system later replaced by Adhan believed to be informed to Abdullah ibn Zayd in his dream, and liked and introduced by Muhammad.

The Emigrants of Mecca, known as Muhajirun, had left almost everything there and came to Medina empty-handed. They were cordially welcomed and helped by the Muslims of Medina, known as Ansar (the helpers). Muhammad made a formal bond of fraternity among them[98] that went a long way in eliminating long-established enmity among various tribes, particularly Aws and Khazraj.[99]

Establishment of a new polity

After the arrival of Muhammad in Medina, its people could be divided into four groups:[100][101]

- The Muslims: emigrants from Mecca and Ansars of Medina.

- The hypocrites; they nominally embraced Islam, but actually were against it.

- Those from Aws and Khazraj who were still pagans, but were inclined to embrace Islam.

- The Jews; they were huge in number and formed an important community there.

In order to establish peaceful coexistence among this heterogeneous population, Muhammad invited the leading personalities of all the communities to reach a formal agreement which would provide a harmony among the communities and security to the city of Medina, and finally drew up the Constitution of Medina, also known as the Medina Charter, which formed "a kind of alliance or federation" among the prevailing communities.[92] It specified the mutual rights and obligations of the Muslims and Jews of Medina, and prohibited any alliance with the outside enemies. It also declared that any dispute would be referred to Muhammad for settlement.[102]

Persistent hostility of Quraysh

Before the arrival of Muhammad, the clans of Medina had suffered a lot from internal feuds and had planned to nominate Abd-Allah ibn Ubaiy as their common leader with a view to restoring peace. The arrival of Muhammad rendered this design unlikely, and from then Abd-Allah ibn Ubaiy began entertaining hostility towards Muhammad. Soon after Muhammad's settlement in Medina, Abd-Allah ibn Ubaiy received an ultimatum from the Quraysh directing him to fight or expel the Muslims from Medina, but was convinced by Muhammad not to do that.[9][103][104] Around this time, Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh, chief of Aws, went to Mecca to perform Umrah. Because of mutual friendship, he was hosted and escorted by a Meccan leader, Umayyah ibn Khalaf, but the two could not escape the notice of Abu Jahl, an archenemy of Islam. At the sight of Sa'ad, Abu Jahl became angry and threatened to stop their visit to Kaaba as his clan had sheltered the Muhammad. Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh also threatened to hinder their trading caravans.[9][104]

Thus, there remained a persistent enmity between the Muslims and the Quraysh tribe.[105] The Muslims were still few and without substantial resources, and fearful of attacks.[9][106]

Causes of and preparation for fighting

Following the emigration, the Meccans seized the properties of the Muslim emigrants in Mecca.[107] The Quraysh leaders of Mecca persecuted the newly converted Muslims there, and they migrated to Medina to avoid persecution, abandoning their properties. Muhammad and the Muslims found themselves in a more precarious situation in Medina than in Mecca.[9][108] Besides the ultimatum of the Quraysh they had to confront the designs of the hypocrites, and had to be wary of the pagans and Jews also.[109] The trading caravans of Quraysh, whose usual route was from Mecca to Syria, used to set the neighboring tribes of Medina against the Muslims, which posed a great danger to the security of Muslims of Medina[110] given that war was common at that time. In view of all this, the Quran granted permission to the persecuted Muslims to defend themselves: "Permission to fight is granted to those against whom war is made, because they have been wronged, and God indeed has the power to help them. They are those who have been driven out of their homes unjustly only because they affirmed: "Our Lord is God"" (Quran 22:39-40). The Quran further justifies taking defensive measures by stating that "And if God had not repelled some men by others, the earth would have been corrupted. But God is a Lord of Kindness to (His) creatures" (Quran 2:251). According to Quranic description, war is an abnormal and unenviable way which, when inevitable, should be limited to minimal casualty, and free from any kind of transgression on the part of the believers.[111] In this regard, the Quran says, "Fight in the cause of God with those who fight you, but do not transgress limits; for God loveth not transgressors" (2:190), and "And fight them on until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail justice and faith in God; but if they cease, let there be no hostility except to those who practice oppression" (2:193).

Thus, to ensure the security of the Ansars and Muhajirun of Medina, Muhammad resorted to the following measures:

- Visiting the neighboring tribes to enter into non-aggression treaty with them to secure Medina from their attacks.[112][113]

- Blocking or intercepting the trading caravans of the Quraysh to compel them into a compromise with the Muslims. As these trading enterprises were the main strength of the Quraysh, Muhammad employed this strategy to reduce their strength.[9]

- Sending small scouting parties to gather intelligence about Quraysh movement, and also to facilitate the evacuation of those Muslims who were still suffering in Mecca and could not migrate to Medina because of their poverty or any other reason.[110] It is in this connection that the following verse of the Quran was revealed: "And why should you not fight in the cause of God and for those who, being weak, are ill-treated (and oppressed)? Men, women, and children, whose cry is: "Our Lord! Rescue us from this town, whose people are oppressors; and raise for us from Thee one who will protect; and raise for us from Thee one who will help!"" (Quran 4:75).

Battle of Badr

A key battle in the early days of Islam, the Battle of Badr was the first large-scale battle between the nascent Islamic community of Medina and their opponent Quraysh of Mecca where the Muslims won a decisive victory. The battle has some background. In 2 AH (623 CE) in the month of Rajab, a Muslim patrolling group attacked a Quraysh trading caravan killing its elite leader Amr ibn Hazrami. The incident happening in a sacred month displeased Muhammad, and enraged the Quraysh to a greater extent.[9][114] The Quran however neutralizes the effect saying that bloodshed in sacred month is obviously prohibited, but Quraysh paganism, persecuting on the Meccan converts, and preventing people from the Sacred Mosque are greater sins (Quran 2:217). Traditional sources say that upon receiving intelligence of a richly laden trading caravan of the Quraysh returning from Syria to Mecca, Muhammad took it as a good opportunity to strike a heavy blow on Meccan power by taking down the caravan in which almost all the Meccan people had invested.[115][116] With full liberty to join or stay back, Muhammad amassed some 313 inadequately prepared men furnished with only two horses and seventy camels, and headed for a place called Badr. Meanwhile, Abu Sufyan, the leader of the caravan, got the information of Muslim march, changed his route towards south-west along Red Sea, and send out a messenger, named Damdam ibn Umar, to Mecca asking for immediate help. The messenger exaggerated the news in a frenzy style of old Arab custom, and misinterpreted the call for protecting the caravan as a call for war.[117][118]

The Quraysh with all its leading personalities except Abu Lahab marched with a heavily equipped army of more than one thousand men with ostentatious opulence of food supply and war materials.[117][119] Abu Sufyan's second message that the trading caravan successfully had escaped the Muslim interception, when reached the Quraish force, did not stop them from entering into a major offensive with the Muslim force, mainly because of the belligerent Quraysh leader Abu Jahl.[9][120] The news of a strong Quraysh army and its intention reaching the Islamic prophet Muhammad, he held a council of war where the followers advised him to go forward. The battle occurred on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH) and resulted in a heavy loss on the Quraysh side: around seventy men, including chief leaders, were killed and a similar number were taken prisoner. Islamic tradition attributes the Muslim victory to the direct intervention of God: he sent down angels that emboldened the Muslims and wreaked damage on the enemy force.[121]

Treason, attacks, and siege

The defeat at the battle of Badr provoked the Quraysh to take revenge on Muslims. Meanwhile, two Qurayshi men – Umayr ibn Wahb and Safwan ibn Umayya – conspired to kill Muhammad. The former went to Medina with a poisoned sword to execute the plan but was detected and brought to Muhammad. It is said that Muhammad himself revealed to Umayr his secret plan and Umayr, upon accepting Islam, began preaching Islam in Mecca.[122][123] The Quraysh soon led an army of 3,000 men and fought the Muslim force, consisting of 700 men, in the Battle of Uhud. Despite initial success in the battle, the Muslims failed to consummate victory due to the mistake of the strategically posted archers. The predicament of Muslims at this battle has been seen by Islamic scholars as a result of disobedience of the command of Muhammad: Muslims realized that they could not succeed unless guided by him.[124]

The Battle of Uhud was followed by a series of aggressive and treacherous activities against the Muslims in Medina. Tulaiha ibn Khuweiled, chief of Banu Asad, and Sufyan ibn Khalid, chief of Banu Lahyan, tried to march against Medina but were rendered unsuccessful. Ten Muslims, recruited by some local tribes to learn the tenets of Islam, were treacherously murdered: eight of them being killed at a place called Raji, and the remaining two being taken to Mecca as captives and killed by Quraysh.[9][125] About the same time, a group of seventy Muslims, sent to propagate Islam to the people of Nejd, was put to a massacre by Amir ibn Tufail's Banu Amir and other tribes. Only two of them escaped, returned to Medina, and informed Muhammad of the incidents.[9][126] Around 5th AH (627 CE), a large combined force of at least 10,000 men from Quraysh, Ghatafan, Banu Asad, and other pagan tribes known as the confederacy was formed to attack the Muslims mainly at the instigation and efforts of Jewish leader Huyayy ibn Akhtab and it marched towards Medina. The trench dug by the Muslims and the adverse weather foiled their siege of Medina, and the confederacy left with heavy losses. The Quran says that God dispersed the disbelievers and thwarted their plans (33:5). The Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, who were allied with Muhammad before the Battle of the Trench, were charged with treason and besieged by the Muslims commanded by Muhammad.[127][128] After Banu Qurayza agreed to accept whatever decision Sa'ad ibn Mua'dh would take about them, Sa'ad pronounced that the male members be executed and the women and children be considered as war captives.[129][130][131][132]

Treaty with the Quraysh

Around 6 AH (628 CE) the nascent Islamic state was somewhat consolidated when Muhammad left Medina to perform pilgrimage at Mecca, but was intercepted en route by the Quraysh who, however, ended up in a treaty with the Muslims known as the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.[133] Though the terms of the Hudaybiyyah treaty were apparently unfavorable to the Muslims of Medina, the Quran declared it as a clear victory (48:1). Muslim historians mention that through the treaty, the Quraysh recognized Muhammad as their equal counterpart and Islam as a rising power,[134] and that the treaty mobilized the contact between the Meccan pagans and the Muslims of Medina resulting in a large number of Quraysh conversion into Islam after being attracted by the Islamic norms.[9]

Victory

Around the end of the 6 AH and the beginning of the 7 AH (628 CE), Muhammad sent letters to various heads of state asking them to accept Islam and to worship only one God.[135] Notable among them were Heraclius, the emperor of Byzantium; Khosrau II, the emperor of Persia; the Negus of Ethiopia; Muqawqis, the ruler of Egypt; Harith Gassani, the governor of Syria; and Munzir ibn Sawa, the ruler of Bahrain. In the 6 AH, Khalid ibn al-Walid accepted Islam who later was to play a decisive role in the expansion of Islamic empire. In the 7 AH, the Jewish leaders of Khaybar – a place some 200 miles from Medina – started instigating the Jewish and Ghatafan tribes against Medina.[9][136] When negotiation failed, Muhammad ordered the blockade of the Khaybar forts, and its inhabitants surrendered after some days. The lands of Khaybar came under Muslim control. Muhammad however granted the Jewish request to retain the lands under their control.[9] In 629 CE (7 AH), in accordance with the terms of the Hudaybiyyah treaty, Muhammad and the Muslims performed their lesser pilgrimage (Umrah) to Mecca and left the city after three days.[137][138]

Conquest of Mecca

In 629 CE, The Banu Bakr tribe, an ally of Quraysh, attacked the Muslims' ally tribe Banu Khuza'a, and killed several of them.[139] The Quraysh openly helped Banu Bakr in their attack, which in return, violated the terms of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah. Of the three options now advanced by Muhammad, they decided to cancel the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.[140] Muhammad started taking preparation for Mecca campaign. On 29 November 629 (6th of Ramadan, 8 AH),[141] Muhammad set out with 10,000 companions, and stopped at a nearby place from Mecca called Marr-uz-Zahran. When Meccan leader Abu Sufyan came to gather intelligence, he was detected and arrested by the guards. Umar ibn al-Khattab wanted the execution of Abu Sufyan for his past offenses, but Muhammad spared his life after he converted to Islam.[142] On 11 December 629 (18th of Ramadan, 8 AH), he entered Mecca almost unresisted, and declared a general amnesty for all those who had committed offences against Islam and himself.[13][14] He then destroyed the idols – placed in and around the Kaaba – reciting the Quranic verse: "Say, the truth has arrived, and falsehood perished. Verily, the falsehood is bound to perish" (Quran 17:81).[15][16] William Muir comments, "The magnanimity with which Muhammad treated a people who had so long hated and rejected him is worthy of all admiration."[143]

Conquest of Arabia

Soon after the Mecca conquest, the Banu Hawazin tribe together with the Banu Thaqif tribe gathered a large army, under the leadership of Malik Ibn 'Awf, to attack the Muslims.[144][145] At this, the Muslim force, which included the newly converts of Mecca, went forward under the leadership of Muhammad, and the two armies met at the valley of Hunayn. Though at first disarrayed at the sudden attack of Hawazin, the Muslim force recollected mainly at the effort of Muhammad, and ultimately defeated the Hawazin. The latter was pursued at various directions.[146][147] After Malik bin 'Awf along with his men took shelter in the fort of Ta'if, the Muslim army besieged it which however yielded no significant result, compelling them to return Medina. Meanwhile, some newly converts from the Hawazin tribe came to Muhammad and made a plea to release their women and children who had been captivated from the battlefield of Hunayn. Their request was granted by the Muslims.[148][149]

After the Mecca conquest and the victory at the Battle of Hunayn, the supremacy of the Muslims was somewhat established throughout the Arabian peninsula.[150][151] Various tribes started to send their representatives to express their loyalty to Muhammad. In the year 9 AH (630 CE), Zakat – which is the obligatory charity in Islam – was introduced and was accepted by most of the people. A few tribes initially refused to pay it, but gradually accepted.[152]

In October 630 CE, upon receiving news that the Byzantine was gathering a large army at the Syrian area to attack Medina, and because of reports of hostility adopted against Muslims,[153] Muhammad arranged his Muslim army, and came out to face them. On the way, they reached a place called Hijr where remnants of the ruined Thamud nation were scattered. Muhammad warned them of the sandstorm typical to the place, and forbade them not to use the well waters there.[9] By the time they reached Tabuk, they got the news of Byzantine's retreat,[154] or according to some sources, they came to know that the news of Byzantine gathering was wrong.[155] Muhammad signed treaties with the bordering tribes who agreed to pay tribute in exchange of getting security. It is said that as these tribes were at the border area between Syria (then under Byzantine control) and Arabia (then under Muslim control), signing treaties with them ensured the security of the whole area.[156] Some months after the return from Tabuk, Muhammad's infant son Ibrahim died which eventually coincided with a sun eclipse. When people said that the eclipse had occurred to mourn Ibrahim's death, Muhammad said: "the sun and the moon are from among the signs of God. The eclipses occur neither for the death nor for the birth of any man".[157][158] After the Tabuk expedition, the Banu Thaqif tribe of Taif sent their representative team to Muhammad to inform their intention of accepting Islam on condition that they be allowed to retain their Lat idol with them and that they be exempted from prayers. Given that there were inconsistent with Islamic principles, Muhammad rejected their demands and said "There is no good in a religion in which prayer is ruled out".[159][160][161] After Banu Thaqif tribe of Taif accepted Islam, many other tribes of Hejaz followed them and declared their allegiance to Islam.[162][163]

Farewell Pilgrimage

In 631 CE, during the Hajj season, Muhammad appointed Abu Bakr to lead 300 Muslims to the pilgrimage in Mecca. As per old custom, many pagans from other parts of Arabia came to Mecca to perform pilgrimage in pre-Islamic manner. Ali, at the direction of Muhammad, delivered a sermon stipulating the new rites of Hajj and abrogating the pagan rites. He especially declared that no unbeliever, pagan, and naked man would be allowed to circumambulate the Kaaba from the next year.[164][165] After this declaration was made, a vast number of people of Bahrain, Yemen, and Yamama, who included both the pagans and the people of the book, gradually embraced Islam. Next year, In 632 CE, Muhammad performed hajj and taught Muslims first-hand the various rites of Hajj.[166][167] On the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah, from Mount Arafat, he delivered his Farewell Sermon in which he abolished old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system, repudiated racial discrimination, and advised people to "be good to women". According to Sunni tafsir, the following Quranic verse was delivered during this event: "Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you" (Quran 5:3).[166][167][168]

Death

Soon after his return from the pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with fever, head pain, and weakness. He was confined to bed by Abu Bakr.[169] During his illness, he appointed Abu Bakr to lead the prayers in the mosque.[170][171] He ordered to donate the last remaining coins in his house as charity. It is narrated in Sahih al-Bukhari that at the time of death, Muhammad was dipping his hands in water and was wiping his face with them saying "There is no god but God; indeed death has its pangs."[172] He died on June 8 632, in Medina, at the age of 62 or 63, in the house of his wife Aisha.[173][174]

Legacy

Final prophet

Muhammad is regarded as the final messenger and prophet by all the main branches of Islam who was sent by God to guide humanity to the right way (Quran 7:157).[1][25][167][175][176] The Quran uses the designation Khatam an-Nabiyyin 33:40 (Arabic: خاتم النبين) which is translated as Seal of the Prophets. The title is generally regarded by Muslims as meaning that Muhammad is the last in the series of prophets beginning with Adam.[177][178][179] The belief that a new prophet cannot arise after Muhammad is shared by both Sunni and Shi'i Muslims.[180][181] Believing Muhammad is the last prophet is a fundamental belief in Islamic theology.[182][183]

Moral character

Muslims believe that Muhammad was the possessor of moral virtues at the highest level, and was a man of moral excellence.[23][167] He represented the 'prototype of human perfection' and was the best among God's creations.[23][184] The 68:4 verse of the Quran says: 'And you [Muhammad] are surely on exalted quality of character'. Consequently, to the Muslims, his life and character are an excellent example to be emulated both at social and spiritual levels.[167][184][185] The virtues that characterize him are modesty and humility, forgiveness and generosity, honesty, justice, patience, and, self-denial.[23][186] Muslim biographers of Muhammad in their books have shed much light on the moral character of Muhammad. Besides, there is a genre of biography that approaches his life focusing on his moral qualities rather than discussing the external affairs of his life.[23][167]

According to biographers, Muhammad lived a simple and austere life often characterized by poverty.[187][188] He was more bashful than a maiden, and was rare to laugh in a loud voice; rather, he preferred soft smiling.[189] Ja'far al-Sadiq, a descendant of Muhammad and an acclaimed scholar, narrated that Muhammad was never seen stretching his legs in a gathering with his companions and when he would shake hands, he would not pull his hand away first.[190] It is said that during the conquest of Mecca, when Muhammad was entering into the city riding on a camel, his head lowered, in gratitude to God, to the extent that it almost touched the back of the camel.[16][189][191] He never took revenge from anyone for his personal cause.[189][192] He maintained honesty and justice in his deeds.[193][194] When an elite woman in Medina was accused of theft, and others pleaded for the mitigation of the penalty, Muhammad said: "Even if my daughter Fatima were accused of theft, I would pronounce the same verdict." He preferred mildness and leniency in behavior and in dealing with affairs,[187][195] and is reported as saying: "He who is not merciful to others, will not be treated mercifully (by God)" (Sahih al-Bukhari, 8:73:42). He pardoned many of his enemies in his life.[196] Biographers especially mention his forgiving the Meccan people after the Conquest of Mecca who at the early period of Islam tortured the Muslims for a long time, and later fought several battles with the Muslims.[13][14]

Muslim veneration

Muhammad is highly venerated by the Muslims,[197] and is sometimes considered by them to be the greatest of all the prophets.[1][20][21] Muslims do not worship Muhammad as worship in Islam is only for God.[21][198][199] In Muhammad's own words, he said: 'Do not extol me as the Christians extolled the son of Mary, I am merely a servant'.[200] Muslim understanding and reverence for Muhammad can largely be traced to the teachings of Quran which emphatically describes Muhammad's exalted status. To begin with, the Quran describes Muhammad as al-nabi al-ummi or unlettered prophet (Quran 7:158), meaning that he "received his religious knowledge only from God".[201] As a result, Muhammad's examples have been understood by the Muslims to represent the highest ideal for human conduct, and to reflect what God wants humanity to do. The Quran ranks Muhammad above previous prophets in terms of his moral excellence and the universal message he brought from God for humanity. The Quran calls him the "beautiful model" (al-uswa al-hasana) for those who hope for God and the last day (Quran 33:21). Muslims believe that Muhammad was sent not for any specific people or region, but for all of humanity.[202]

Muslims venerate Muhammad in various ways:

- In proclamation of Islamic faith, the attestation to oneness of God is always followed by the declaration "verily, I bear witness that Muhammad is the messenger of God".[24]

- In speaking or writing, Muslims attach the title "Prophet" to Muhammad's name, and always follow it with sallallahu 'alayhi wa sallam (صَلّى الله عليه وسلّم, "Peace be upon him"),[24] sometimes abbreviated SAW, PBUH, or ﷺ.

- Muhammad's tomb in Medina is considered the second most holy place for Muslims,[201] and is visited by most pilgrims who go to Mecca for Hajj.[203][204]

- Muslims often use various titles of praise and appellations to express Muhammad's exalted status.[24]

Sunnah: A model for Muslims

For more than thirteen hundred years Muslims have modeled their lives after their prophet Muhammad. They awaken every morning as he awakened; they eat as he ate; they wash as he washed; and they behave even in the minutest acts of daily life as he behaved.

— S. A. Nigosian

In Muslim legal and religious thought, Muhammad, inspired by God to act wisely and in accordance with his will, provides an example that complements God's revelation as expressed in the Quran; and his actions and sayings – known as Sunnah – are a model for Muslim conduct.[205] The Sunnah can be defined as "the actions, decisions, and practices that Muhammad approved, allowed, or condoned".[206] It also includes Muhammad's confirmation to someone's particular action or manner (during Muhammad's lifetime) which, when communicated to Muhammad, was generally approved by him.[207] The Sunnah, as recorded in the Hadith literature, encompasses everyday activities related to men's domestic, social, economic, political life.[206] It addresses a broad array of activities and Islamic beliefs ranging from the simple practices like, for example, the proper way of entering into a mosque, and private cleanliness to the most sublime questions involving the love between God and humans.[208] The Sunnah of Muhammad serves as a model for the Muslims to shape their life in that light. The Quran tells the believers to offer prayer, to fast, to perform pilgrimage, to pay Zakat, but it was Muhammad who practically taught the believers how to perform all these.[208] In Islamic theology, the necessity to follow the examples (the Sunnah) of Muhammad comes from the ruling of the Quran which it describes in its numerous verses. One such typical verse is "And obey God and the Messenger so that you may be blessed" (Quran 3:132). The Quran uses two different terms to denote this: ita’ah (to obey) and ittiba (to follow). The former refers to the orders of Muhammad, and the latter to his acts and practices.[209] Muhammad often stressed the importance of education and intelligence in the Muslim Ummah because it removes ignorance and promotes acceptance and tolerance. This can be illustrated when Muhammad advises his cousin Ali that, "No poverty is more severe than ignorance and no property is more valuable than intelligence."[190]

Pre-existence

Muslims also venerate Muhammad as the manifestation of the Muhammadan Light.[210] Accordingly, Muhammad's spirit already existed before the creation of the world and he was actually the first prophet created, but the last who was sent.[211] A hadith from Al-Tirmidhi states, that Muhammad was once asked, when his prophethood was decreed and he answered: "When Adam was between the spirit and the body." A more popular, but less authenticated version states,[211] that Muhammad answered: "when Adam was between water and mud."[212] Both Sunni and Shia sources later elaborated cosmogonic scenarios in which the world emanated from the light of Muhammad.[211] According to a Sunni tradition, when Adam was in heaven, he read an inscription on the throne of God of the Shahada, Muhammad already mentioned. There also exists an extended version in Shia traditions. Therefore, the Shahada does not only mention Muhammad, but also Ali.[213]

However the idea of Muhammad's pre-existence was also a controversial one and disputed by some scholars like Al-Ghazali and Ibn Taymiyyah.[214] Although the notion of the pre-existing Muhammad takes some resemblance of the Christian doctrine of the pre-existence of Christ, in Islam there can not be found any trace of Muhammad as a second person within the Godhead.[215]

Muhammad as lawgiver

In Islamic Sharia, the Sunnah of Muhammad is regarded a vital source for Islamic law, next in importance only to the Quran.[216][217] Additionally, the Quran in its several verses authorizes Muhammad, in his capacity as a prophet, to promulgate new laws. The 7:157 verse of the Quran says, "those who follow the Messenger, the unlettered Prophet whom they find written down in the Torah and the Injil, and who (Muhammad) bids them to the Fair and forbids them the Unfair, and makes lawful for them the good things, and makes unlawful for them the impure things,... So, those who believe in him, and honor him, and help him, and follow the light that has been sent down with him (Muhammad) – they are the ones who acquire success." Commenting on this verse, Islamic scholar Muhammad Taqi Usmani says, "one of the functions of the Holy Prophet (saaw) is to make lawful the good things and make unlawful the impure things. This function has been separated from bidding the fair and forbidding the unfair, because the latter relates to the preaching of what has already been established as fair, and warning against what is established as unfair, while the former embodies the making of lawful and unlawful".[218] Taqi Usmani recognizes two kinds of revelations – the "recited" one which is collectively known as Quran, and the "unrecited" one that Muhammad received from time to time to let him know God's will regarding how human affairs should be – and concludes that Muhammad's prophetic authority to promulgate new laws had its base on the later type. Therefore, in Islamic theology, the difference between God's authority and that of his messenger is of great significance: the former is wholly independent, intrinsic and self-existent, while the authority of the latter is derived from and dependent on the revelation from God.[219][220]

Muhammad as intercessor

Muslims see Muhammad as primary intercessor and believe that he will intercede on behalf of the believers on Last Judgment day.[221] This non-Qur'anic vision of Muhammad's eschatological role appears for the first time in the inscriptions of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, completed in 72/691-692.[222] Islamic tradition narrates that after resurrection when humanity will be gathered together and they will face distress due to heat and fear, they will come to Muhammad. Then he will intercede for them with God and the judgment will start.[223] Hadith narrates that Muhammad will also intercede for the believers who for their sins have been taken to hell. Muhammad's intercession will be granted and a lot of believers will come out of hell.[224]

Muhammad and the Quran

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

|

To Muslims, the Quran is the verbatim word of God which was revealed, through Gabriel, to Muhammad[225] who delivered it to people without any change (Q53:2-5,[226] 26:192-195),[227] Thus, there exists a deep relationship between Muhammad and the Quran. Muslims believe that as a recipient of the Quran, Muhammad was the man who best understood the meaning of the Quran, was its chief interpreter, and was granted by God "the understanding of all levels of Quran's meaning".[228] In Islamic theology, if a report of Muhammad's Quranic interpretation is held to be authentic, then no other interpretative statement has higher theoretical value or importance than that.[217]

In Islamic belief, though the inner message of all the divine revelations given to Muhammad is essentially the same, there has been a "gradual evolution toward a final, perfect revelation".[229] It is in this case that Muhammad's revelation excels the previous ones as Muhammad's revelation is considered by the Muslims to be "the completion, culmination, and perfection of all the previous revelations".[229] Consequently, when the Quran declares that Muhammad is the final prophet after which there will be no future prophet (Q33:40),[230] it is also meant that the Quran is the last revealed divine book.

Names and titles of praise

Muhammad is often referenced with these titles of praise or epithet:

- an-Nabi, 'the Prophet';

- ar-Rasul, 'the Messenger';

- al-Habeeb, 'the beloved';

- al-Muṣṭafa, 'the chosen one' (Quran 22:75);

- al-Amin, 'the trustworthy' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:52:237);

- as-Sadiq, 'the honest'(Quran 33:22);

- al-Haq, 'the truthful' (Quran 10:08);

- ar-Rauf, 'the kind' (Quran 9:128);

- ‘alā khuluq ‘aẓīm (Arabic: عَلَى خُلُق عِظِيْم), 'on an exalted standard of character' (Quran 68:4);

- al-Insan al-Kamil, 'the perfect man';[231]

- Uswah Ḥasan (Arabic: أُسْوَة حَسَن), 'good example' (Quran 33:21);

- al-Khatim an-Nabiyin, 'the seal of the prophets' (Quran 33:40);

- ar-Rahmatul lil 'alameen, 'mercy of all the worlds' (Quran 21:107);

- as-Shaheed, 'the witness' (Quran 33:45);

- al-Mubashir, 'the bearer of good tidings' (Quran 11:2);

- an-Nathir, 'the warner' (Quran 11:2);

- al-Mudhakkir, 'the reminder' (Quran 88:21);

- ad-Da'i, 'the one who calls [unto God]' (Quran 12:108);

- al-Bashir, 'the announcer' (Quran 2:119);

- an-Noor, 'the light personified' (Quran 05:15);

- as-Siraj-un-Munir, 'the light-giving lamp' (Quran 33:46);

- al-Kareem, 'the noble' (Quran 69:40);

- an-Nimatullah, 'the divine favour' (Quran 16:83);

- al-Muzzammil, 'the wrapped' (Quran 73:01);

- al-Muddathir, 'the shrouded' (Quran 74:01);

- al-'Aqib, 'the last [prophet]' (Sahih Muslim, 4:1859, Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732);

- al-Mutawakkil, 'the one who puts his trust [in God]' (Quran 9:129);

- al-Kutham, 'the generous one’

- al-Mahi, 'the eraser [of disbelief]' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732);

- al-Muqaffi, 'the one who followed [all other prophets]';

- an-Nabiyyu at-Tawbah, 'the prophet of penitence’

- al-Fatih, 'the opener';

- al-Hashir, 'the gatherer (the first to be resurrected) on the day of judgement' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 4:56:732);

- as-Shafe'e, 'the intercessor' (Sahih al-Bukhari, 9:93:601, Quran 3:159, Quran 4:64, Quran 60:12);

- al-Mushaffaun, 'the one whose intercession shall be granted' (Quran 19:87, Quran 20:109).

He also has these names:

Miracles

_05.jpg.webp)

Several miracles are said to have been performed by Muhammad.[233] Muslim scholar Jalaluddin Al-Suyuti, in his book Al Khasais-ul-Kubra, extensively discussed Muhammad's various miracles and extraordinary events. Traditional sources, indicate that Sura 54:1-2 refers to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh.[234][235]

Isra and Mi'raj

The Isra and Mi'raj are the two parts of a "Night Journey" that, according to Islamic tradition, Muhammad took during a single night around the year 621. It has been described as both a physical and spiritual journey.[236] A brief sketch of the story is in Sura (chapter) 17 Al-Isra of the Quran,[237] and other details come from the hadith.[238] In the journey, Muhammad riding on Buraq travels to the Masjid Al-Aqsa (the farthest mosque) in Jerusalem where he leads other prophets in prayer. He then ascends to the heavens, and meets some of the earlier prophets such as Abraham, Joseph, Moses, John the Baptist, and Jesus.[238] During this Night Journey, God offered Muhammad five-time daily prayer for the believers.[239][240][238] According to traditions, the Journey is associated with the Lailaṫ al-Isrā' wal-Mi'rāj (Arabic: لَيلَة الإِِسرَاء والمِعرَاج), as one of the most significant events in the Islamic calendar.[241]

Splitting of the Moon

Islamic tradition credits Muhammad with the miracle of the splitting of the moon.[242][243] According to Islamic account, once when Muhammad was in Mecca, the pagans asked him to display a miracle as a proof of his prophethood. It was night time, and Muhammad prayed to God. The moon split into two and descended on two sides of a mountain. The pagans were still incredulous about the credibility of the event but later heard from the distant travelers that they also had witnessed the splitting of the moon.[242][243] Islamic tradition also tends to refute the arguments against the miracle raised by some quarters.[244]

During the Battle of the Trench

On the eve of the Battle of the Trench when the Muslims were digging a ditch, they encountered a firmly embedded rock that could not be removed. It is said that Muhammad, when apprised of this, came and, taking an axe, struck the rock that created spark upon which he glorified God and said he had been given the keys of the kingdom of Syria. He struck the rock for a second time in a likewise manner and said he had been given the keys of Persia and he could see its white palaces. A third strike crushed the rock into pieces whereupon he again glorified God and said he had been given the keys of Yemen and he could see the gates of Sana. According to Muslim historians, these prophesies were fulfilled in subsequent times.[245][246]

The Spider and the Dove

When Muhammad and his close friend Abu Bakr had been threatened by the Quraysh, on their way to Medina, they hid themselves in Mount Thawr's cave. The cave had been concealed by a spider building a web and a dove building a nest at the entrance after they entered the cave,[247] therefore killing a spider became associated with sin.[248]

Visual representation

Although Islam only explicitly condemns depicting the divinity, the prohibition was supplementally expanded to prophets and saints and among Arab Sunnism, to any living creature.[249] Although both the Sunni schools of law and the Shia jurisprudence alike prohibit the figurative depiction of Muhammad,[250] visual representations of Muhammad exist in Arabic and Ottoman Turkish texts and especially flourished during the Ilkhanate (1256-1353), Timurid (1370-1506), and Safavid (1501-1722) periods. But apart from these notable exceptions and modern-day Iran,[251] depictions of Muhammad were rare, and if given, usually with his face veiled.[252][253]

Most modern Muslims believe that visual depictions of all the prophets of Islam should be prohibited[254] and are particularly averse to visual representations of Muhammad.[255] One concern is that the use of images can encourage idolatry, but also creating an image might lead the artist to claim the ability to create, an ability only ascribed to God.[256]

Gallery

A view of Taif with a road at the foreground and mountains at the background. Muhammad went there to preach Islam

A view of Taif with a road at the foreground and mountains at the background. Muhammad went there to preach Islam Masjid an-Nabawi

Masjid an-Nabawi Inside view of Masjid an-Nabawi

Inside view of Masjid an-Nabawi The Green Dome built over Muhammad's tomb

The Green Dome built over Muhammad's tomb Part of Al-Masjid an-Nabawi where Muhammad's tomb is situated

Part of Al-Masjid an-Nabawi where Muhammad's tomb is situated.jpg.webp) Masjid an-Nabawi at sunset

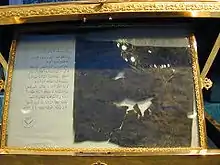

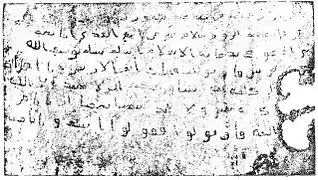

Masjid an-Nabawi at sunset Facsimile of a letter sent by Muhammad to the Munzir Bin Sawa Al-Tamimi, governor of Bahrain

Facsimile of a letter sent by Muhammad to the Munzir Bin Sawa Al-Tamimi, governor of Bahrain Muhammad's letter To Heraclius

Muhammad's letter To Heraclius

See also

- Children of Muhammad

- List of biographies of Muhammad

- Islamic mythology

- Muhammad and the Bible

- Mahammaddim

- Muhammad in the Quran

- Relics of Muhammad

- Stories of The Prophets

Notes

- Opinions about the exact date of Muhammad's birth slightly vary. Shibli Nomani and Philip Khuri Hitti fixed the date to be 571 CE. But August 20, 570 CE is generally accepted. See Muir, vol. ii, pp. 13–14 for further information.

References

- Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511233-7.

- Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- Peters, F.E. (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-691-11553-5.

- Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-0-19-511234-4.

- "Muhammad (prophet)". Microsoft® Student 2008 [DVD] (Encarta Encyclopedia). Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation. 2007.

- Khan, Majid Ali (1998). Muhammad the final messenger (1998 ed.). India: Islamic Book Service. p. 332. ISBN 978-81-85738-25-3.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Muir, William (1861). Life of Mahomet. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 55.

- Shibli Nomani. Sirat-un-Nabi. Vol 1 Lahore.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 116.

- "Muhammad". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Ghali, Muhammad M (2004). The History of Muhammad: The Prophet and Messenger. Cairo: Al-Falah Foundation. p. 5. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Ramadan, Tariq (2007). In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-530880-8.

- Husayn Haykal, Muhammad (2008). The Life of Muhammad. Selangor: Islamic Book Trust. pp. 438–9 & 441. ISBN 978-983-9154-17-7.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 118.

- Ramadan, Tariq (2007). In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-19-530880-8.

- Campo (2009), "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 494

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press. pp. 261–300. ISBN 978-0-19-577307-1.

- Richard Foltz, "Internationalization of Islam", Encarta Historical Essays.

- Morgan, Garry R (2012). Understanding World Religions in 15 Minutes a Day. Baker Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4412-5988-2. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Mead, Jean (2008). Why Is Muhammad Important to Muslims. Evans Brothers. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-237-53409-7. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Riedling, Ann Marlow (2014). Is Your God My God. WestBow Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4908-4038-3. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Matt Stefon, ed. (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. New York City: Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-61530-060-0.

- Matt Stefon (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices, p. 18

- Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- Muhammad Shafi Usmani. Tafsir Maariful Quran (PDF). Vol. 6. p. 236. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-02-19.

- Virani, Shafique N. (2011). "Taqiyya and Identity in a South Asian Community". The Journal of Asian Studies. 70 (1): 99–139. doi:10.1017/S0021911810002974. ISSN 0021-9118. S2CID 143431047. p. 128.

-

- Conrad, Lawrence I. (1987). "Abraha and Muhammad: some observations apropos of chronology and literary topoi in the early Arabic historical tradition1". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 50 (2): 225–40. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00049016. S2CID 162350288.

- Sherrard Beaumont Burnaby (1901). Elements of the Jewish and Muhammadan calendars: with rules and tables and explanatory notes on the Julian and Gregorian calendars. G. Bell. p. 465.

- Hamidullah, Muhammad (February 1969). "The Nasi', the Hijrah Calendar and the Need of Preparing a New Concordance for the Hijrah and Gregorian Eras: Why the Existing Western Concordances are Not to be Relied Upon" (PDF). The Islamic Review & Arab Affairs: 6–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2012.

- Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad (PDF). Madras. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Article "AL-SHĀM" by C.E. Bosworth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 9 (1997), page 261.

- Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I.B.Tauris. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-16.

To the Arabs, this same territory, which the Romans considered Arabian, formed part of what they called Bilad al-Sham, which was their own name for Syria. From the classical perspective however Syria, including Palestine, formed no more than the western fringes of what was reckoned to be Arabia between the first line of cities and the coast. Since there is no clear dividing line between what are called today the Syrian and Arabian deserts, which actually form one stretch of arid tableland, the classical concept of what actually constituted Syria had more to its credit geographically than the vaguer Arab concept of Syria as Bilad al-Sham. Under the Romans, there was actually a province of Syria, with its capital at Antioch, which carried the name of the territory. Otherwise, down the centuries, Syria like Arabia and Mesopotamia was no more than a geographic expression. In Islamic times, the Arab geographers used the name arabicized as Suriyah, to denote one special region of Bilad al-Sham, which was the middle section of the valley of the Orontes river, in the vicinity of the towns of Homs and Hama. They also noted that it was an old name for the whole of Bilad al-Sham which had gone out of use. As a geographic expression, however, the name Syria survived in its original classical sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and also in the Syriac literature of some of the Eastern Christian churches, from which it occasionally found its way into Christian Arabic usage. It was only in the nineteenth century that the use of the name was revived in its modern Arabic form, frequently as Suriyya rather than the older Suriyah, to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham: first of all in the Christian Arabic literature of the period, and under the influence of Western Europe. By the end of that century it had already replaced the name of Bilad al-Sham even in Muslim Arabic usage.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Ali, Muhammad (2011). Introduction to the Study of The Holy Qur'an. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-934271-21-6. Archived from the original on 2015-10-29.

- Ramadan, Tariq (2007). In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-530880-8.

- Muir, William (1861). Life of Mahomet. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. xvii-xviii. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Stefon, Islamic Beliefs and Practices, pp. 22–23

- Al Mubarakpuri, Safi ur Rahman (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar). Darussalam. p. 74. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8. Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- Ramadan (2007), p. 16

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Al Mubarakpuri (2002); Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar) pp. 81–3

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Sell (1913), p. 12

- Ramadan, Tariq (2007). In the Footsteps of the Prophet: Lessons from the Life of Muhammad. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-530880-8.

- Al Mubarakpuri (2002). Al-Fudoul Confederacy. p. 77. ISBN 9789960899558. Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- Stefon, Islamic Beliefs and Practices, p. 24

- Al Mubarakpuri (2002); p. 80

- Brown, Daniel (2003). A New Introduction to Islam. Blackwell Publishing Professional. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-631-21604-9.

- Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 29.

- Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (2008). The Life of Muhammad. p. 77. ISBN 9789839154177.

- Bogle, Emory C. (1998). Islam: Origin and Belief. Texas University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-292-70862-4.

- Quran 96:1–5

- Sell (1913), p. 30

- Ramadan (2007), p. 30

- Al Mubarakpuri (2002); "Gabriel brings down the Revelation", pp. 86-7

- Richard S. Hess; Gordon J. Wenham (1998). Make the Old Testament Live: From Curriculum to Classroom. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4427-9. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "The Absolute Truth About Muhammad in the Bible With Arabic Titles". Truth Will Prevail Productions. Archived from the original on 2016-09-09. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- Muhammad foretold in the Bible: An Introduction Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Abdus Sattar Ghauri, retrieved July 3, 2010

- Campo (2009), "Revelation", Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 589

- "Introduction" (PDF). Tafsir Maariful Quran. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-09-15.

- Juan E. Campo, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts on File. pp. 570–573. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC&pg=PA570.

The Quran is the sacred scripture of Islam. Muslims believe it contains the infallible word of God as revealed to Muhammad the Prophet in the Arabic language during the latter part of his life, between the years 610 and 632… (p. 570). Quran was revealed piecemeal during Muhammad’s life, between 610 C.E. and 632 C.E., and that it was collected into a physical book (mushaf) only after his death. Early commentaries and Islamic historical sources support this understanding of the Quran’s early development, although they are unclear in other respects. They report that the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656) ordered a committee headed by Zayd ibn Thabit (d. ca. 655), Muhammad’s scribe, to establish a single authoritative recension of the Quran… (p. 572-3).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Oliver Leaman, ed. (2006). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 520. ISBN 9-78-0-415-32639-1 https://books.google.com/books?id=isDgI0-0Ip4C&pg=PA520.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Matt Stefon, ed. (2010). Islamic Beliefs and Practices. New York City: Britannica Educational Publishing. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-1-61530-060-0.

- Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-253-21627-4.

- Campo (2009), "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 492.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Juan E. Campo, ed. (2009). "Muhammad". Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts on File. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-8160-5454-1.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. Macmillan and Co. pp. 113–4.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1946). History of the Arabs. Macmillan and Co. p. 114.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (2008). The Life of Muhammad. pp. 98 & 105–6. ISBN 9789839154177.

- Al-Mubarakpuri (2002). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. p. 141. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8.

- Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (2008). The Life of Muhammad. pp. 144–5. ISBN 9789839154177.

- William Muir (1861). Life of Mahomet. vol. vol. 2, p.181

- Al-Mubarakpuri (2002). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8.

- Armstrong, Karen (2002). Islam: A Short History. New York City: Modern Library. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8129-6618-3.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2011). Muhammad: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-955928-2. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16.

- Al-Mubarakpuri (2002). The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. p. 165. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8.

- Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 70.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 71.

- Husayn Haykal, Muhammad (2008). The Life of Muhammad. Selangor: Islamic Book Trust. pp. 169–70. ISBN 978-983-9154-17-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 70–1. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Sell, Edward (1913). The Life of Muhammad. Madras: Smith, Elder, & Co. p. 76.

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

Accordingly, within a very short period, despite the opposition of the Quraysh, most of the Muslims in Mecca managed to migrate to Yathrib.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. IA. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Ibn Kathir (2001). Stories of the Prophet: From Adam to Muhammad. Mansoura, Egypt: Dar Al-Manarah. p. 389. ISBN 978-977-6005-17-4.

- "Ya-Seen Ninth Verse". Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014. Quran Surah Yaseen ( Verse 9 )

- Shaikh, Fazlur Rehman (2001). Chronology of Prophetic Events. London: Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd. pp. 51–52.

- F. A. Shamsi, "The Date of Hijrah", Islamic Studies 23 (1984): 189-224, 289-323 (JSTOR link 1 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine + JSTOR link 2 Archived 2016-12-26 at the Wayback Machine).

- Armstrong (2002), p. 14

- Muir (1861), vol. 3, p. 17

- Ibn Kathir (2001), Translated by Sayed Gad, p. 396

- Khan, Muhammad Zafrullah (1980). Muhammad: Seal of the Prophets. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7100-0610-3.

- Sell (1913), pp. 86-87.

- Campo (2009), Muhammad, Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 493

- Al Mubarakpuri, Safi ur Rahman (2002). "The attempts of the Quraysh to provoke the Muslims". The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Darussalam. ISBN 978-9960-899-55-8. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27. Retrieved 2011-11-11.