Forgiveness

Forgiveness, in a psychological sense, is the intentional and voluntary process by which one who may initially feel victimized or wronged, goes through a change in feelings and attitude regarding a given offender, and overcomes the impact of the offense including [1][2][3] negative emotions such as resentment and a desire for vengeance (however justified it might be). Theorists differ, however, in the extent to which they believe forgiveness also implies replacing the negative emotions with positive attitudes (i.e. an increased ability to tolerate the offender).[4][5][6] In certain legal contexts, forgiveness is a term for absolving or giving up all claims on account of debt, loan, obligation, or other claims.[7][8]

On the psychological level, forgiveness is different from simple condoning (viewing an action as harmful, yet to be “forgiven” or overlooked for certain reasons of “charity”), excusing or pardoning (merely releasing the offender from responsibility for an action), or forgetting (attempting to somehow remove from one's conscious mind, the memory of a given “offense"). In some schools of thought, it involves a personal and "voluntary" effort at the self-transformation of one's own half of a relationship with another, such that one's own self is restored to peace and ideally to what psychologist Carl Rogers has referred to as “unconditional positive regard” towards the other.[4][9]

As a psychological concept and virtue, the benefits of forgiveness have been explored in religious thought, social sciences and medicine. Forgiveness may be considered simply in terms of the person who forgives[10] including forgiving themselves, in terms of the person forgiven or in terms of the relationship between the forgiver and the person forgiven. In most contexts, forgiveness is granted without any expectation of restorative justice, and without any response on the part of the offender (for example, one may forgive a person who is incommunicado or dead). In practical terms, it may be necessary for the offender to offer some form of acknowledgment, an apology, or even just ask for forgiveness, in order for the wronged person to believe themselves able to forgive as well.[4]

Social and political dimensions of forgiveness involves the strictly private and religious sphere of "forgiveness". The notion of "forgiveness" is generally considered unusual in the political field. However, Hannah Arendt considers that the "faculty of forgiveness" has its place in public affairs. The philosopher believes that forgiveness can liberate resources both individually and collectively in the face of the irreparable. During an investigation in Rwanda on the discourses and practices of forgiveness after the 1994 genocide, sociologist Benoit Guillou illustrated the extreme polysemy (multiple meanings) of the word "forgiveness" but also the eminently political character of the notion. By way of conclusion of his work, the author proposes four main figures of forgiveness to better understand, on the one hand, ambiguous uses and, on the other hand, the conditions under which forgiveness can mediate a resumption of social link.[11]

Most world religions include teachings on the nature of forgiveness, and many of these teachings provide an underlying basis for many varying modern day traditions and practices of forgiveness. Some religious doctrines or philosophies place greater emphasis on the need for humans to find some sort of divine forgiveness for their own shortcomings, others place greater emphasis on the need for humans to practice forgiveness of one another, yet others make little or no distinction between human and divine forgiveness.

The term forgiveness can be used interchangeably and is interpreted many different ways by people and cultures. This is specifically important in relational communication because forgiveness is a key component in communication and the overall progression as an individual and couple or group. When all parties have a mutual viewing for forgiveness then a relationship can be maintained. "Understanding antecedents of forgiveness, exploring the physiology of forgiveness, and training people to become more forgiving all imply that we have a shared meaning for the term".[12]

Research

Although there is presently no consensus for a psychological definition of forgiveness in research literature, agreement has emerged that forgiveness is a process, and a number of models describing the process of forgiveness have been published, including one from a radical behavioral perspective.[13]

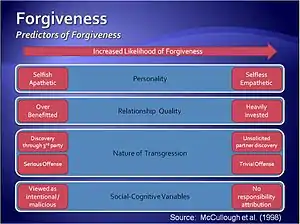

Dr. Robert Enright from the University of Wisconsin–Madison founded the International Forgiveness Institute and is considered the initiator of forgiveness studies. He developed a 20-Step Process Model of Forgiveness.[14] Recent work has focused on what kind of person is more likely to be forgiving. A longitudinal study showed that people who were generally more neurotic, angry, and hostile in life were less likely to forgive another person even after a long time had passed. Specifically, these people were more likely to still avoid their transgressor and want to enact revenge upon them two and a half years after the transgression.[15]

Studies show that people who forgive are happier and healthier than those who hold resentments.[16] The first study to look at how forgiveness improves physical health discovered that when people think about forgiving an offender it leads to improved functioning in their cardiovascular and nervous systems.[17] Another study at the University of Wisconsin found the more forgiving people were, the less they suffered from a wide range of illnesses. The less forgiving people reported a greater number of health problems.[18]

The research of Dr. Fred Luskin of Stanford University, and author of the book Forgive for Good[19] presented evidence that forgiveness can be learned (i.e. can be a teachable skill, with practice) based on research projects into the effects of teaching forgiveness: giving empirical validity to the concept that forgiveness is powerful as well as excellent for your health. In three separate studies, including one with Catholics and Protestants from Northern Ireland whose family members were murdered in the political violence, he found that people who are taught how to forgive become less angry, feel less hurt, are more optimistic, become more forgiving in a variety of situations, and become more compassionate and self-confident. His studies show a reduction in experience of stress, physical manifestations of stress, and an increase in vitality.[20]

Ideas about what forgiveness is not

- Forgiveness is not condoning[4][20]

- Forgiveness is not forgetting[4][20]

- Forgiveness is not excusing (i.e. making reasons to explain away offender's responsibility or free will)[4][20]

- Forgiveness doesn't have to be religious or otherworldly[20]

- Forgiveness is not minimizing your hurt[20]

- Forgiveness is not reconciliation (i.e. reestablishing trust in the relationship)[4][20][21]

- Forgiveness is not denying or suppressing anger; rather its focus is on resentment.[22][23][24][20]—in particular, in order to forgive it is healthy to acknowledge and express negative emotions, before you can even forgive[25]

- Forgiveness is not ignoring accountability or justice[26][27]—in particular, punishment and recompensation are independent of the choice to forgive (you can forgive, or not forgive, and still pursue punishment and/or recompensation, regardless)[28][29][30]

- Forgiveness is not pardoning; it cannot be granted or chosen by someone else[4][20]

- Emotional forgiveness is not the same as decisional forgiveness or the expression of forgiveness. Expressing emotions (i.e., "I am angry at you" or "I forgive you") is not the same as genuinely having or experiencing the emotions (i.e., people can deny, mistake, or lie about their emotional experience to another person while genuinely feeling something else instead)[29][31][32]

- Although heavily debated,[6] emotional forgiveness is for you, not the offender[20] (i.e., unless you choose to make it so: by expressing it, or by trying to reconcile)

The timeliness of forgiveness

The psychologist Wanda Malcolm writes a chapter in Women's Reflections on the Complexities of Forgiveness titled "the Timeliness of Forgiveness Interventions" where she outlines reasons why forgiveness takes time: when work on self (care/healing) takes priority (i.e. therapy, medical injuries, etc.), when issues of relational safety need to be addressed, and where facilitating forgiveness may be premature immediately after an interpersonal offense.[25] Malcolm explains that "premature efforts to facilitate forgiveness may be a sign of our reluctance to witness our client’s pain and suffering and may unwittingly reinforce the client’s belief that the pain and suffering is too much to bear and must be suppressed or avoided."[25]

Worthington (et al.) observed that “anything done to promote forgiveness has little impact unless substantial time is spent at helping participants think through and emotionally experience their forgiveness”.[33] Efforts to facilitate forgiveness may be premature immediately after an interpersonal injury,[25] if not harmful.[34]

Indeed, if you make forgiveness a goal, it remains elusive, like a carrot on a stick; just when you think you've got it, it's out of reach again. But when you focus on self-compassion and develop your core-values, forgiveness sneaks up on you. If you realize that you've forgiven your betrayer, it will be after the fact (of detachment or full emotional reinvestment), not before. [35]

Religious views

Religion can have an impact on how someone chooses to forgive and the process they go through. Most have conceptualized religion's effect in three ways—through religious activity, religious affiliation and teachings, and imitation.[36] There are several thousand religions in the world and each one can look at forgiveness a different way.

Judaism

In Judaism, if a person causes harm, but then sincerely and honestly apologizes to the wronged individual and tries to rectify the wrong, the wronged individual is encouraged, but not required, to grant forgiveness:

- "It is forbidden to be obdurate and not allow yourself to be appeased. On the contrary, one should be easily pacified and find it difficult to become angry. When asked by an offender for forgiveness, one should forgive with a sincere mind and a willing spirit ... forgiveness is natural to the seed of Israel." (Mishneh Torah, Teshuvah 2:10)

In Judaism, one must go "to those he has harmed" in order to be entitled to forgiveness.[37] [One who sincerely apologizes three times for a wrong committed against another has fulfilled their obligation to seek forgiveness. (Shulchan Aruch) OC 606:1] This means that in Judaism a person cannot obtain forgiveness from God for wrongs the person has done to other people. This also means that, unless the victim forgave the perpetrator before he died, murder is unforgivable in Judaism, and they will answer to God for it, though the victims' family and friends can forgive the murderer for the grief they caused them. The Tefila Zaka meditation, which is recited just before Yom Kippur, closes with the following:

- "I know that there is no one so righteous that they have not wronged another, financially or physically, through deed or speech. This pains my heart within me, because wrongs between humans and their fellow are not atoned by Yom Kippur, until the wronged one is appeased. Because of this, my heart breaks within me, and my bones tremble; for even the day of death does not atone for such sins. Therefore I prostrate and beg before You, to have mercy on me, and grant me grace, compassion, and mercy in Your eyes and in the eyes of all people. For behold, I forgive with a final and resolved forgiveness anyone who has wronged me, whether in person or property, even if they slandered me, or spread falsehoods against me. So I release anyone who has injured me either in person or in property, or has committed any manner of sin that one may commit against another [except for legally enforceable business obligations, and except for someone who has deliberately harmed me with the thought ‘I can harm him because he will forgive me']. Except for these two, I fully and finally forgive everyone; may no one be punished because of me. And just as I forgive everyone, so may You grant me grace in the eyes of others, that they too forgive me absolutely."

Thus the "reward" for forgiving others is not God's forgiveness for wrongs done to others, but rather help in obtaining forgiveness from the other person.

Sir Jonathan Sacks, chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth, summarized: "it is not that God forgives, while human beings do not. To the contrary, we believe that just as only God can forgive sins against God, so only human beings can forgive sins against human beings."[38]

Jews observe a Day of Atonement Yom Kippur on the day before God makes decisions regarding what will happen during the coming year.[37] Just prior to Yom Kippur, Jews will ask forgiveness of those they have wronged during the prior year (if they have not already done so).[37] During Yom Kippur itself, Jews fast and pray for God's forgiveness for the transgressions they have made against God in the prior year.[37] Sincere repentance is required, and once again, God can only forgive one for the sins one has committed against God; this is why it is necessary for Jews also to seek the forgiveness of those people who they have wronged.[37]

Christianity

Forgiveness is central to Christian ethics and is a frequent topic in sermons and theological works, because Christianity is about Christ, Christ is about redemption, and redemption is about forgiveness of sin.

God's forgiveness

Unlike in Judaism, God can forgive sins committed by people against people, since he can forgive every sin except for the eternal sin, and forgiveness from one's victim is not necessary for salvation.[39] The Parable of the Prodigal Son[40] is perhaps the best known parable about forgiveness and refers to God's forgiveness for those who repent. Jesus asked for God's forgiveness of those who crucified him. "And Jesus said, 'Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.'" – Luke 23:34[41]

Forgiving others

Forgiving offenses is among the spiritual works of mercy,[42] and forgiving others begets being forgiven by God.[43] Considering Mark 11:25, and Matthew 6:14–15, that follows the Lord's Prayer, "For if you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins,"[44] forgiveness is not an option to a Christian, rather one must forgive to be a Christian. Forgiveness in Christianity is a manifestation of submission to Christ and fellow believers.[45]

In the New Testament, Jesus speaks of the importance of forgiving or showing mercy toward others. This is based on the belief that God forgives sins through faith in the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ in his death (1 John 2:2[46]) and that, therefore, Christians should forgive others (Ephesians 4:32[47]). Jesus used the parable of the unmerciful servant (Matthew 18:21–35[48]) to show that His followers (represented in the parable by the servant) should forgive because God (represented by the king) forgives much more.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus repeatedly spoke of forgiveness: "Blessed are the merciful, for they will be shown mercy." Matthew 5:7 (NIV)[49] "Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to your brother; then come and offer your gift." Matthew 5:23–24 (NIV)[50] "And when you stand praying, if you hold anything against anyone, forgive him, so that your Father in heaven may forgive you your sins." Mark 11:25 (NIV)[51] "But I tell you who hear me: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also." Luke 6:27–29 (NIV)[52] "Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful." Luke 6:36 (NIV)[53] "Do not judge, and you will not be judged. Do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven." Luke 6:37 (NIV)[54]

Elsewhere, it is said "Then Peter came to Him and said, "Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? Up to seven times?" Jesus said to him, "I do not say to you, up to seven times, but up to seventy times seven." Matthew 18:21–22 (NKJV)[55]

Benedict XVI, on a visit to Lebanon in 2012, insisted that peace must be based on mutual forgiveness: "Only forgiveness, given and received, can lay lasting foundations for reconciliation and universal peace".[56]

Pope Francis during a General Audience explained forgiving others as God forgives oneself.[57]

Islam

Part of a series on Islam |

| God in Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Islam teaches that Allah is Al-Ghaffur "The Oft-Forgiving", and is the original source of all forgiveness (ghufran غفران). Seeking forgiveness from Allah with repentance is a virtue.[58][59][60]

(...) Allah forgives what is past: for repetition Allah will exact from him the penalty. For Allah is Exalted, and Lord of Retribution.

— Quran 5:95

Islam recommends forgiveness, because Allah values forgiveness. There are numerous verses in Quran and the Hadiths recommending forgiveness. However, Islam also allows revenge to the extent harm done, but forgiveness is encouraged, with a promise of reward from Allah.[61][62]

The recompense for an injury is an injury equal thereto (in degree): but if a person forgives and makes reconciliation, his reward is due from Allah: for (Allah) loveth not those who do wrong.

— Quran 42:40

Afw (عفو is another term for forgiveness in Islam; it occurs 35 times in Quran, and in some Islamic theological studies, it is used interchangeably with ghufran.[58][59][63] Afw means to pardon, to excuse for a fault or an offense. According to Muhammad Amanullah,[64] forgiveness ('Afw) in Islam is derived from three wisdoms. First and the most important wisdom of forgiveness is that it is merciful when the victim or guardian of the victim accepts money instead of revenge.[65][66] The second wisdom of forgiveness is that it increases honor and prestige of the one who forgives.[64] Forgiveness is not a sign of weakness, humiliation or dishonor.[59] Forgiveness is honor, raises the merit of the forgiver in the eyes of Allah, and enables a forgiver to enter paradise.[64] The third wisdom of forgiveness is that according to some scholars, such as al-Tabari and al-Qurtubi, forgiveness expiates (kaffarah) the forgiver from the sins they may have committed at other occasions in life.[59][67] Forgiveness is a form of charity (sadaqat). Forgiveness comes from taqwa (piety), a quality of God-fearing people.[64]

Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í Writings, this explanation is given of how to be forgiving individuals toward others:

"Love the creatures for the sake of God and not for themselves. You will never become angry or impatient if you love them for the sake of God. Humanity is not perfect. There are imperfections in every human being, and you will always become unhappy if you look toward the people themselves. But if you look toward God, you will love them and be kind to them, for the world of God is the world of perfection and complete mercy. Therefore, do not look at the shortcomings of anybody; see with the sight of forgiveness."

— `Abdu'l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, p. 92

Buddhism

In Buddhism, forgiveness is seen as a practice to prevent harmful thoughts from causing havoc on one's mental well-being.[68] Buddhism recognizes that feelings of hatred and ill-will leave a lasting effect on our mind karma. Instead, Buddhism encourages the cultivation of thoughts that leave a wholesome effect. "In contemplating the law of karma, we realize that it is not a matter of seeking revenge but of practicing mettā and forgiveness, for the victimizer is, truly, the most unfortunate of all."[69] When resentments have already arisen, the Buddhist view is to calmly proceed to release them by going back to their roots. Buddhism centers on release from delusion and suffering through meditation and receiving insight into the nature of reality. Buddhism questions the reality of the passions that make forgiveness necessary as well as the reality of the objects of those passions.[70] "If we haven’t forgiven, we keep creating an identity around our pain, and that is what is reborn. That is what suffers."[71]

Buddhism places much emphasis on the concepts of Mettā (loving kindness), karuna (compassion), mudita (sympathetic joy), and upekkhā (equanimity), as a means to avoiding resentments in the first place. These reflections are used to understand the context of suffering in the world, both our own and the suffering of others.

- "He abused me, he struck me, he overcame me, he robbed me’ — in those who harbor such thoughts hatred will never cease."

- "He abused me, he struck me, he overcame me, he robbed me’ — in those who do not harbor such thoughts hatred will cease."

- (Dhammapada 1.3–4; trans. Radhakrishnan – see article)[72]

Hindu Dharma

In Vedic literature and epics of Hinduism, Ksama or Kshyama (Sanskrit: क्षमा)[77] and fusion words based on it, describe the concept of forgiveness. The word ksama is often combined with kripa (tenderness), daya (kindness) and karuna (करुणा, compassion) in Sanskrit texts.[78] In Rg Veda, forgiveness is discussed in verses dedicated to deity Varuna, both the context of the one who has done wrong and one who is wronged.[79][80] Forgiveness is considered one of the six cardinal virtues in Hindu Dharma.

The theological basis for forgiveness in Hindu Dharma is that a person who does not forgive carries a baggage of memories of the wrong, of negative feelings, of anger and unresolved emotions that affect their present as well as future. In Hindu Dharma, not only should one forgive others, but one must also seek forgiveness if one has wronged someone else.[78] Forgiveness is to be sought from the individual wronged, as well as society at large, by acts of charity, purification, fasting, rituals and meditative introspection.

The concept of forgiveness is further refined in Hindu Dharma by rhetorically contrasting it in feminine and masculine form. In feminine form, one form of forgiveness is explained through Lakshmi (called Goddess Sri in some parts of India); the other form is explained in the masculine form through her husband Vishnu.[78] Feminine Lakshmi forgives even when the one who does wrong does not repent. Masculine Vishnu, on the other hand, forgives only when the wrongdoer repents. In Hindu Dharma, the feminine forgiveness granted without repentance by Lakshmi is higher and more noble than the masculine forgiveness granted only after there is repentance. In the Hindu epic Ramayana, Sita – the wife of King Rama – is symbolically eulogized for forgiving a crow even as it harms her. Later in the epic Ramayana, she is eulogized again for forgiving those who harass her while she has been kidnapped in Lanka.[78] Many other Hindu stories discuss forgiveness with or without repentance.[81]

The concept of forgiveness is treated in extensive debates of Hindu literature. In some Hindu texts,[82] certain sins and intentional acts are debated as naturally unforgivable; for example, murder and rape; these ancient scholars argue whether blanket forgiveness is morally justifiable in every circumstance, and whether forgiveness encourages crime, disrespect, social disorder and people not taking you seriously.[83] Other ancient Hindu texts highlight that forgiveness is not same as reconciliation.

Forgiveness in Hindu Dharma does not necessarily require that one reconcile with the offender, nor does it rule out reconciliation in some situations. Instead forgiveness in Hindu philosophy is being compassionate, tender, kind and letting go of the harm or hurt caused by someone or something else.[84] Forgiveness is essential for one to free oneself from negative thoughts, and being able to focus on blissfully living a moral and ethical life (dharmic life).[78] In the highest self-realized state, forgiveness becomes the essence of one's personality, where the persecuted person remains unaffected, without agitation, without feeling like a victim, free from anger (akrodhi).[85][86]

Other epics and ancient literature of Hindu Dharma discuss forgiveness. For example:

Forgiveness is virtue; forgiveness is sacrifice; forgiveness is the Vedas; forgiveness is the Shruti.

Forgiveness protecteth the ascetic merit of the future; forgiveness is asceticism; forgiveness is holiness; and by forgiveness is it that the universe is held together.

Righteousness is the one highest good, forgiveness is the one supreme peace, knowledge is one supreme contentment, and benevolence, one sole happiness.

Janak asked: "Oh lord, how does one attain wisdom? how does liberation happen?"

Ashtavakra replied: "Oh beloved, if you want liberation, then renounce imagined passions as poison, take forgiveness, innocence, compassion, contentment and truth as nectar; (...)"

Jainism

In Jainism, forgiveness is one of the main virtues that needs to be cultivated by the Jains. Kṣamāpanā or supreme forgiveness forms part of one of the ten characteristics of dharma.[91] In the Jain prayer, (pratikramana) Jains repeatedly seek forgiveness from various creatures—even from ekindriyas or single sensed beings like plants and microorganisms that they may have harmed while eating and doing routine activities.[92] Forgiveness is asked by uttering the phrase, Micchāmi dukkaḍaṃ. Micchāmi dukkaḍaṃ is a Prakrit language phrase literally meaning "may all the evil that has been done be fruitless."[93] During samvatsari—the last day of Jain festival paryusana—Jains utter the phrase Micchami Dukkadam after pratikraman. As a matter of ritual, they personally greet their friends and relatives micchāmi dukkaḍaṃ seeking their forgiveness. No private quarrel or dispute may be carried beyond samvatsari, and letters and telephone calls are made to the outstation friends and relatives asking their forgiveness.[94]

Pratikraman also contains the following prayer:[95]

Khāmemi savva-jīve savvë jive khamantu me /

metti me savva-bhūesu, veraṃ mejjha na keṇavi //

(I ask pardon of all creatures, may all creatures pardon me.

May I have friendship with all beings and enmity with none.)

In their daily prayers and samayika, Jains recite Iryavahi sutra seeking forgiveness from all creatures while involved in routine activities:[96]

May you, O Revered One! Voluntarily permit me. I would like to confess my sinful acts committed while walking. I honour your permission. I desire to absolve myself of the sinful acts by confessing them. I seek forgiveness from all those living beings which I may have tortured while walking, coming and going, treading on living organism, seeds, green grass, dew drops, ant hills, moss, live water, live earth, spider web and others. I seek forgiveness from all these living beings, be they — one sensed, two sensed, three sensed, four sensed or five sensed. Which I may have kicked, covered with dust, rubbed with ground, collided with other, turned upside down, tormented, frightened, shifted from one place to another or killed and deprived them of their lives. (By confessing) may I be absolved of all these sins.

Jain texts quote Māhavīra on forgiveness:[97]

By practicing prāyaṣcitta (repentance), a soul gets rid of sins, and commits no transgressions; he who correctly practises prāyaṣcitta gains the road and the reward of the road, he wins the reward of good conduct. By begging forgiveness he obtains happiness of mind; thereby he acquires a kind disposition towards all kinds of living beings; by this kind disposition he obtains purity of character and freedom from fear.

— Māhavīra in Uttarādhyayana Sūtra 29:17–18

Even the code of conduct amongst the monks requires the monks to ask forgiveness for all transgressions:[98]

If among monks or nuns occurs a quarrel or dispute or dissension, the young monk should ask forgiveness of the superior, and the superior of the young monk. They should forgive and ask forgiveness, appease and be appeased, and converse without restraint. For him who is appeased, there will be success (in control); for him who is not appeased, there will be no success; therefore one should appease one's self. 'Why has this been said, Sir? Peace is the essence of monasticism'.

— Kalpa Sūtra 8:59

Hoʻoponopono

Hoʻoponopono is an ancient Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness, combined with prayer. Similar forgiveness practices were performed on islands throughout the South Pacific, including Samoa, Tahiti and New Zealand. Traditionally Hoʻoponopono is practiced by healing priests or kahuna lapaʻau among family members of a person who is physically ill. Modern versions are performed within the family by a family elder, or by the individual alone.

Popular recognition

The need to forgive is widely recognized by the public, but they are often at a loss for ways to accomplish it. For example, in a large representative sampling of American people on various religious topics in 1988, the Gallup Organization found that 94% said it was important to forgive, but 85% said they needed some outside help to be able to forgive. However, not even regular prayer was found to be effective.

Akin to forgiveness is mercy, so even if a person is not able to complete the forgiveness process they can still show mercy, especially when so many wrongs are done out of weakness rather than malice. The Gallup poll revealed that the only thing that was effective was "meditative prayer".[99]

Forgiveness as a tool has been extensively used in restorative justice programs,[100] after the abolition of apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Africa), run for victims and perpetrators of Rwandan genocide, the violence in Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and Northern Ireland conflict, which has also been documented in film, Beyond Right and Wrong: Stories of Justice and Forgiveness (2012).[101][102]

Forgiveness theory can be found and applied to religion, relationships, health, individual, interventions, and much more. Forgiveness is an important trait to understand and possess because it is something that everyone has to experience in their both personal and professional life.

Forgiveness is associated with the theory of emotion because it is largely drawn from a person's emotional connection and level with the situation. Forgiveness is something that most people are taught to understand and practice at a young age. Because forgiveness is an emotion there is not an exact originator of it but there are several theorists, psychologists, and sociologists who link it to other theories or apply theories to help understand the concept. The philosopher Joseph Butler (Fifteen Sermons) defined forgiveness as "overcoming of resentment, the overcoming of moral hatred, as a speech act, and as forbearance".[103]

Forgiveness in relationships

Forgiveness in marriage is an important aspect in a marriage. When two individuals are able to forgive each other it results in a long happy marriage. Forgiveness can help prevent problems from accruing in the married couple's future.[104]

In a 2005 study, researchers were interested in figuring out whether forgiveness is important in a marriage. When does forgiveness usually accrue? Does it accrue before an argument or after an argument? Does forgiveness take a role when a person breaks a promise? etc.[104] Researchers found six components that were related to forgiveness in marriage and explains how each one relates to forgiveness. The six components are: satisfaction, ambivalence, conflict, attributions, empathy and commitment.[104]

Researchers provided an overview of forgiveness in marriage and how individuals in a relationship believe that if forgiveness accrues then you must forget what had happened.[104] Moreover, based on the interventions and recommendations the researchers started to see how important forgiveness is in a relationship and how it can lead to a happy and healthy relationship.[104]

In a 2005 study, researchers mentioned that when couples forgive their spouses they sometimes need help from professionals to overcome their pain that might be left behind.[104] Researchers also described the difference between how each individual perceives the situation based on who is in pain and who caused the pain. Also how the couple react to the situation based on their feelings and how they personally respond to the situation.[104]

The act and effects of forgiveness can vary depending on the relationship status between persons. Whether you are married, friends, or even just acquaintances, the process of forgiving is similar but not completely the same. When it comes to forgiving a friend,the friend's personal situation and feelings must also be considered. You must ask yourself if you were in the wrong or if the other person could already be going through some type of grief or suffering at the time of the incident. Consideration of other people's feelings plays a factor as to how much and how quickly a situation can be resolved.[105]

The model of forgiveness:

"Enright's model of forgiveness has received empirical support and sees forgiveness as a journey through four phases" which are:[104]

- Uncovering phase: Emphases on exploring the pain that the individual has experienced.

- Decision phase: The nature of forgiveness is discussed. Also the individual commits that they will try to forgive the spouse

- Work phase: The focus shifts to the transgressor in an effort to gain insight and understanding.

- Deepening phase': The victim moves toward resolution, becoming aware that he/she is not alone, having been the recipient of others' forgiveness, and finds meaning and purpose in the forgiveness process.[104]

Furthermore, when married couples argue they tend to focus on who is right and who is wrong. Also couples tend to focus on who proves the other wrong which can cause more problems and can make the problem worse because it will make it harder to forgive one another.[104]

Recommendation and interventions:

The researchers also came up with recommendation for practitioners and intervention to help individuals that are married on how to communicate with each other, how to resolve problems and how to make it easier to forgive each other.[104] Some of the interventions of forgiveness in marriage has been a great success. It encouraged forgiveness and made couples happier together.[104]

Some of the recommendations that was given to practitioners was that the individuals had to explore and understand what forgiveness means before starting any intervention because the preconceived idea of forgiveness can cause problems with couples being open to forgive.[104] For example, an individual not forgiving their spouse out of fear that the spouse might think that they are weak which can cause a conflict.[104] It was stated that the couple must know the following:

- Forgiveness takes

- The different forms of forgiveness

- The danger in communicating in forgiveness

- That Perpetrators and victims have different perceptive context is important[104]

Furthermore, the researchers thought of ways to further help married couples in the future and suggested that they should explore the following:

- The importance of seeking forgiveness

- Self-forgiveness

- The role of the sacred in marital forgiveness[104]

Relationships are at the sentiment aspect of our lives; with our families at home and friends outside. Relationships interact in schools and universities, with work mates and, with colleagues at the workplace and in our diverse communities. In the article it states, the quality of these relationships determines our individual well-being, how well we learn, develop and function, our sense of connectedness with others and the health so society.[106]

In 2002, two innovators of Positive Psychology, Ed Diener and Martin Seligman, conducted a study at the University of Illinois on the 10% of students with the highest scores recorded on a survey of personal happiness. What they came up with was most salient characteristics shared by students who were very content and showed positive life styles were the ones who "their strong ties to friends and family and commitment to spending time with them."[107]

A study done in 2000, identified as a key study that taken part and examined two natures of relationships (friends and family) and at what age does the support switch importance from one to the other. The study showed that people whom had good family relationship were able to have more positive outside relationships with friends. Through the family relationship and friendships, the character of the individual was built to forgive and learn from the experience in the family.[108]

In 2001, Charlotte vanOyen Witvliet asked people to think about someone who had hurt, wronged, or offended them. As they thought to answer, she observed their reaction. She observed their blood pressure, heart rate, facial muscle tension, and sweat gland activity. To deliberate on an old misdemeanor is to practice unforgiveness. The outcome to the recall of the grudge the candidates’ blood pressure and heart rate increased, and they sweated more. Pondering about their resents was stressful, and subjects found the rumination unpleasant. When they adept forgiveness, their physical stimulation glided downward. They showed no more of an anxiety reaction than normal wakefulness produces.[109]

In 2013, study on self-forgiveness with spouse forgiveness has a better outcome to a healthier life by Pelucchi, Paleari, Regalia and Fincham. This study investigates self-forgiveness for real hurts committed against the partner in a romantic relationship (168 couples). For both males and females, the mistaken partners were more content with their romantic relationship to the extent that they had more positive and less negative sentiment and thoughts toward themselves. In the study when looking at the victimized partners were more gratified with the relationship when the offending partner had less negative sentiment and thoughts towards themselves. It concludes that self-forgiveness when in a relationship has positive impact on both the offending and victimized partner.[110]

Forgiveness interventions

Both negative and positive affect play a role in forgiveness interventions. It is the general consensus across researchers in the field of psychology, that the overarching purpose of forgiveness interventions is to decrease overall negative affect associated with the stimulus and increase the individual's positive affect.[111][112]

The disease model has been mainly used in regards to therapy, however the incorporation of forgiveness into therapy has been lacking,[111] and has been slowly gaining popularity in the last couple of decades.[111] More recent research has shown how the growth of forgiveness in psychology has given rise to the study of forgiveness interventions.[111]

Different types

There are various forms of forgiveness interventions.[111] One common adaptation used by researchers is where patients are forced to confront the entity preventing them from forgiving by using introspective techniques and expressing this to the therapist.[111][112] Another popular forgiveness intervention is getting individual to try to see things from the offender's point of view. The end goal for this adaptation is getting the individual to perhaps understand the reasoning behind the offender's actions.[111][112] If they are able to do this then they might be able to forgive the offender more easily.[111][112] Over the past years, there have been researchers who have studied forgiveness interventions in relationships and whether or not prayer increases forgiveness. A study conducted in 2009 found that simply just by praying for a friend or thinking positive thoughts about that individual every day for four weeks demonstrates how prayer positively boosts the chances of forgiving a friend or partner which leads to a better relationship.[113]

There is, however, conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of forgiveness interventions.[111]

Contrary evidence

Although research has taken into account the positive aspects of forgiveness interventions, there are also negative aspects that have been explored as well. Some researchers have taken a critical approach and have been less accepting of the forgiveness intervention approach to therapy.[111]

Critics have argued that forgiveness interventions may actually cause an increase in negative affect because it is trying to inhibit the individual's own personal feelings towards the offender. This can result in the individual feeling negatively towards themself.[111] This approach is categorizing the individual's feelings by implying that the negative emotions the individual is feeling are unacceptable and feelings of forgiveness is the correct and acceptable way to feel. It might inadvertently promote feelings of shame and contrition within the individual.[111]

Wanda Malcolm, a registered psychologist, states: "that it is not a good idea to make forgiveness an a-priori goal of therapy".[25] Steven Stosny, also adds, that you heal first then forgive (NOT forgive then heal);[23] that fully acknowledging the grievance (both what actions were harmful, and naming the emotions the victim felt as a response to the offenders actions) is an essential first step, before forgiveness can occur.[114]

Some researchers also worry that forgiveness interventions will promote unhealthy relationships.[111][115] They worry that individuals with toxic relationships will continue to forgive those who continuously commit wrong acts towards them when in fact they should be distancing themselves from these sorts of people.[111][115]

A number of studies showcase high effectiveness rates of forgiveness interventions when done continuously over a long period of time.[111] Some researchers have found that these interventions have been proven ineffective when done over short spans of time.[111]

Forgiveness interventions: children

There has been some research within the last decade outlining some studies that have looked at the effectiveness of forgiveness interventions on young children. There have also been several studies done studying this cross culturally.[111] One study that explored this relationship, was a study conducted in 2009 by Eadaoin Hui and Tat Sing Chau. In this study, Hui and Chau looked at the relationship between forgiveness interventions and Chinese children who were less likely to forgive those who had wronged them.[111] The findings of this study showed that there was an effect of forgiveness interventions on the young Chinese children.[111]

Forgiveness interventions: older adults

Older adults that receive forgiveness interventions report higher levels of forgiveness than those that did not receive treatment. Furthermore, forgiveness treatments resulted in lower depression, stress and anger than no treatment conditions. Forgiveness interventions also enhance positive psychological aspects. The specific intervention model (Enright’s or Worthington’s proposal) and format (group or individual) are not associated with better outcomes.[116]

Forgiveness and mental health

Survey data from 2000 showed that 61% of participants that were part of a small religious group reported that the group helped them be more forgiving.[117] Individuals reported that their religion groups which promote forgiveness was related to self-reports of success in overcoming addictions, guilt, and perceiving encouragement when feeling discouraged.[117]

It is suggested that mindfulness plays a role in forgiveness and health.[118] The forgiveness of others has a positive effect on physical health when it is combined with mindfulness but evidence shows that forgiveness only effects health as a function of mindfulness.[118]

A study from 2005 states that self-forgiveness is an important part of self-acceptance and mental health in later life.[119] The inability to self-forgive can compromise mental health.[119] For some elderly people, self-forgiveness requires reflecting on a transgression to avoid repeating wrongdoings, individuals seek to learn from these transgressions in order to improve their real self-schemas.[119] When individuals are successful at learning from these transgressions, they may experience improved mental health.[119]

A study in 2015 looks at how self-forgiveness can reduce feelings of guilt and shame associated with hypersexual behavior.[120] Hypersexual behaviour can have negative effects on individuals by causing distress and life problems.[120] Self-forgiveness may be a component that can help individuals reduce hypersexual negative behaviours that cause problems.[120]

Evidence shows that self-forgiveness and procrastination may be associated; self-forgiveness allows the individual to overcome the negatives associated with an earlier behaviour and engage in approach-oriented behaviours on a similar task.[121] Learning to forgive oneself for procrastination can be positive because it can promote self-worth and may cause positive mental health.[121] Self-forgiveness for procrastination may also reduce procrastination.[121]

Everett Worthington, Loren Toussaint and David R. Williams, PhD, proclaimed to have enough research on the effects of forgiveness towards mental health and wrote the self-help book Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health detailing the multiple benefits and psychological results of forgiveness to humans mentally and physically. Toussaint and Worthington claim that stress relief can be the chief factor that connects forgiveness and well-being. Toussaint also found that levels of stress went down when levels of forgiveness rose up, resulting in a decrease in mental health symptoms.[122]

Forgiveness gives people a sense that their burden being lifted because they are no longer feeling anger or hatred toward their transgressor. They even begin to understand their transgressor. Since negative emotions and stress are removed from the person seeking forgiveness, overall well-being is improved. They begin to have positive emotions and determinations in life.[123]

Forgiveness and physical health

The correlation between forgiveness and physical health is a concept that has recently gained traction in research. Some studies claim that there is no correlation, either positive or negative between forgiveness and physical health, and others show a positive correlation.[124]

Evidence supporting a correlation

Individuals with forgiveness as a personality trait have been shown to have overall better physical health. In a study on relationships, regardless if someone was in a negative or positive relationship, their physical health seemed to be influenced at least partially by their level of forgiveness.[125]

Individuals who make a decision to genuinely forgive someone are also shown to have better physical health. This is due to the relationship between forgiveness and stress reduction. Forgiveness is seen as preventing poor physical health and managing good physical health.[126]

Specifically individuals who choose to forgive another after a transgression have lower blood pressure and lower cortisol levels than those who do not. This is theorized to be due to various direct and indirect influences of forgiveness, which point to forgiveness as an evolutionary trait. See Broaden and Build Theory.[126]

Direct influences include: Reducing hostility (which is inversely correlated with physical health), and the concept that unforgiveness may reduce the immune system because it puts stress on the individual. Indirect influences are more related to forgiveness as a personality trait and include: forgiving people may have more social support and less stressful marriages, and forgiveness may be related to personality traits that are correlated with physical health.[126]

Forgiveness may also be correlated with physical health because hostility is associated with poor coronary performance. Unforgiveness is as an act of hostility, and forgiveness as an act of letting go of hostility. Heart patients who are treated with therapy that includes forgiveness to reduce hostility have improved cardiac health compared to those who are treated with medicine alone.[124]

Forgiveness may also lead to better perceived physical health. This correlation applies to both self-forgiveness and other-forgiveness but is especially true of self-forgiveness. Individuals who are more capable of forgiving themselves have better perceived physical health.[127]

Individuals who partake in forgiving people can sometimes be benefited from the act. For example, people who are willing to forgive others can get healthier hearts, fewer depression symptoms, and less anxiety. Obviously, forgiveness can be seen as somewhat helpful towards mental health especially with people who have mental disorders. Forgiveness can also lead to specific people getting a better immune system.[128]

Criticisms

Forgiveness studies have been refuted by critics who claim that there is no direct correlation between forgiveness and physical health. Forgiveness, due to the reduction of directed anger, contributes to mental health and mental health contributes to physical health, but there is no evidence that forgiveness directly improves physical health. Most of the studies on forgiveness cannot isolate it as an independent variable in an individual's well-being, so it is difficult to prove causation.[129] Further studies imply that while there is not enough research to directly relate forgiveness to physical health there are factors that can be implied. This relates more to physiological measures and what happens to a body during the stages of forgiveness in their daily life.[130]

Additionally, research into the correlation between physical health and forgiveness has been criticized for being too focused on unforgiveness. Research shows more about what hostility and unforgiveness contribute to poor health than it shows what forgiveness contributes to physical health.[129] Additionally, research notes that unforgiving or holding grudges can contribute to adverse health outcomes by perpetuating anger and heightening SNS arousal and cardiovascular reactivity. Expression of anger has been strongly associated with chronically elevated blood pressure and with the aggregation of platelets, which may increase vulnerability for heart disease.[130]

Self-forgiveness

Self-forgiveness happens in situations where an individual has done something that they perceive to be morally wrong and they consider themselves to be responsible for the wrongdoing.[131] Self-forgiveness is the overcoming of negative emotions that the wrongdoer associates with the wrongful action.[131] Negative emotions associated with wrongful action can include guilt, regret, remorse, blame, shame, self-hatred and/or self-contempt.[131]

Major life events that include trauma can cause individuals to experience feelings of guilt or self-hatred.[132] Humans have the ability to reflect on their behaviours to determine if their actions are moral.[132] In situations of trauma, humans can choose to self-forgive by allowing themselves to change and live a moral life.[132] Self-forgiveness may be required in situations where the individual hurt themselves or in situations where they hurt others.[132] Indeed, self-forgiveness has been shown to have a moderating effect between depression and suicidality: suggesting self-forgiveness (up-to a point) as not only a protective factor of suicide, but also hinting at possible prevention strategies.[133]

Therapeutic model

Individuals can unintentionally cause harm or offence to one another in everyday life. It is important for individuals to be able to recognize when this happens, and in the process of making amends, have the ability to self-forgive.[134] Specific research suggests that the ability to genuinely forgive one's self can be significantly beneficial to an individual's emotional as well as mental well-being.[135] The research indicates that the ability to forgive one's self for past offences can lead to decreased feelings of negative emotions such as shame and guilt, and can increase the use of more positive practices such as self-kindness and self-compassion.[135] However, it has been indicated that it is possible for the process of self-forgiveness to be misinterpreted and therefore not accurately completed.[134] This could potentially lead to increased feelings of regret or self-blame.[135] In an attempt to avoid this, and increase the positive benefits associated with genuine self-forgiveness, a specific therapeutic model of self-forgiveness has been recommended, which can be used to encourage genuine self-forgiveness in offenders. The model that has been proposed has four key elements. These elements include responsibility, remorse, restoration and renewal.[135]

- The therapeutic model suggests responsibility as the first necessary step towards genuine self-forgiveness.[135] Research advises that in order to avoid the negative affect associated with emotions such as overwhelming guilt or regret, offenders must first recognize that they have hurt another individual, and accept the responsibility necessary for their actions.[134][135]

- Once the individual has accepted responsibility for their offences, it is natural for them to experience feelings of remorse or guilt. However, these feelings can be genuinely processed and expressed preceding the need for restoration.[135]

- The act of restoration allows the offending individual to make the necessary amends to the individual(s) they have hurt.

- The final component in the model of self-forgiveness is renewal'. The offending individual is able to genuinely forgive himself/herself for their past transgressions and can engage in more positive and meaningful behaviors such as self-compassion and self-kindness.[135]

Despite the suggested model, research advises that the process of self-forgiveness is not always applicable for every individual.[135] For example, individuals who have not actually caused others any harm or wrongdoing, but instead are suffering from negative emotions such as self-hatred or self-pity, such as victims of assault, might attempt self-forgiveness for their perceived offences. However, this would not be the process necessary for them to make their amends.[135] Additionally, offenders who continue to offend others while attempting to forgive themselves for past offences demonstrate a reluctance to genuinely complete the four stages necessary for self-forgiveness.[135] Research suggests that it is important to first gather exterior information about the individual's perceived offences as well as their needs and motivation for self-forgiveness.[135]

Unapologetic forgiveness

Being unapologetic is often something that humans come across at some point in their lives, and there has been much research on if a person refuses to apologize or even recognized the wrongdoings. This can then often lead into how one would go into forgiving the unapologetic party and "the relationship between apologies and the adjectives 'apologetic' and 'unapologetic' is not quite so straightforward."[136] People struggle with forgiving people that have done wrongful actions. Causing a person to not forgive themselves or another. It relates to how people feel about the person who is asking for forgiveness. Choosing to forgive someone or not correlates to whether that person is truly sorry for their actions or not.[137] Forgiving a person who does not seem remorseful for their actions can be difficult, but may loosen the grip the person has over you. Intrusive thoughts can cause the person who wants to forgive, to have feelings of low self-worth, and endure a traumatic phase due to that person's actions.[138] Going through a negative experience in your life can cause long term trauma. It can stay in your memory just like a good one. A bad experience will be there too. Holding on to negative emotion is the driving fuel of why people may struggle to heal from their problems in their mind. Having thoughts of revenge may not help a person to heal from the past experience that led them to harbor those negative emotions. They may benefit from letting go and accepting what has happened.[139] Letting go does not erase what the person did, but forgiveness can lead to inner-peace from the lack of negative emotion within. Despite the other person not apologizing sincerely, forgiving them may be the solution to problems and result in loving one's self.[140]

Character retributivism

- Forgiveness could be offered only at significant temporal remove from the wrongdoing.

- The enforcement of justice, at least with regard to punishing or rewarding, falls outside the purview of personal forgiveness.

- Forgiveness operates at a different level than justice.[136]

Jean Hampton

Jean Hampton sees the decision to forgive the unrepentant wrongdoer as expressing a commitment "to see a wrongdoer in a new, more favorable light" as one who is not completely rotten or morally dead.[136]

See also

- A Course in Miracles

- Anantarika-karma

- Clementia, Roman goddess of forgiveness (and Eleos, her Greek counterpart)

- Compassion

- Contrition

- Ethics in religion

- Ho'oponopono

- Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops

- Pardon

- Regret

- Relational transgressions

- Remorse

- Repentance

- Resentment

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Unconditional love

References

Citations

- Doka, Kenneth (2017). Grief is a journey. Atria Books. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-1476771519.

- Hieronymi, Pamela (May 2001). "Articulating an Uncomprimising Forgiveness" (PDF). pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- North, Joanna (1998). Exploring Forgiveness (1998). University of Wisconsin. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0299157741.

- "American Psychological Association. Forgiveness: A Sampling of Research Results." (PDF). 2006. pp. 5–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-26. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- What Is Forgiveness? Archived 2013-11-14 at the Wayback Machine The Greater Good Science Center, University of California, Berkeley

- Field, Courtney; Zander, Jaimie; Hall, Guy (September 2013). "'Forgiveness is a present to yourself as well': An intrapersonal model of forgiveness in victims of violent crime". International Review of Victimology. 19 (3): 235–247. doi:10.1177/0269758013492752. ISSN 0269-7580. S2CID 145625500.

- Debt Forgiveness Archived 2013-10-31 at the Wayback Machine OECD, Glossary of Statistical Terms (2001)

- Loan Forgiveness Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine Glossary, U.S. Department of Education

- Rogers, Carl (1956). Client-Centered Therapy (3 ed.). Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

- Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- "Benoît Guillou, Le pardon est-il durable ? Une enquête au Rwanda, Paris, François Bourin". 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-11-05.

- Lawler-Row, Kathleen A.; Scott, Cynthia A.; Raines, Rachel L.; Edlis-Matityahou, Meirav; Moore, Erin W. (2007-06-01). "The Varieties of Forgiveness Experience: Working toward a Comprehensive Definition of Forgiveness". Journal of Religion and Health. 46 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1007/s10943-006-9077-y. ISSN 1573-6571. S2CID 33474665.

- Cordova, J., Cautilli, J., Simon, C. & Axelrod-Sabtig, R (2006). BAO "Behavior Analysis of Forgiveness in Couples Therapy". IJBCT, 2(2), p. 192 Archived 2008-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Dr. Robert Enright, Forgiveness Is a Choice, American Psychological Association, 2001 ISBN 1-55798-757-2

- Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Day, L., Kon, T. W. H., Colley, A., and Linley, P. A. (2008). "Personality predictors of levels of forgiveness two and a half years after the transgression". Archived 2009-03-19 at the Wayback Machine Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1088–1094.

- "Forgiving (Campaign for Forgiveness Research)". 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- Van Oyen, C. Witvilet, T.E. Ludwig and K. L. Vander Lann, "Granting Forgiveness or Harboring Grudges: Implications for Emotions, Physiology and Health," Psychological Science no. 12 (2001):117–23

- S. Sarinopoulos, "Forgiveness and Physical Health: A Doctoral Dissertation Summary," World of Forgiveness no. 2 (2000): 16–18

- "Learningtoforgive.com". Learningtoforgive.com. 2014-06-20. Archived from the original on 2016-06-09. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- Fred, Luskin (September 2003). Forgive for Good: A Proven Prescription for Health & Happiness. HarperOne. p. 7–8. ISBN 978-0062517210.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Worthington, Everett. "Everett Worthington - Justice, Forgiveness, and Reconciliation: How Psychology Informs Theology". Youtube. GordonConwell. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Romm, Cari (11 January 2017). "Rushing to Forgiveness is not a Binary State". The Cut. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Stosny, Steven (September 1, 2013). Living & Loving after Betrayal. New Harbinger Publications. p. 227. ISBN 978-1608827527.

- "Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Emotion Accounts (of what forgiveness is). Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- Malcolm, Wanda (Oct 19, 2007). Women's Reflections on the Complexities of Forgiveness. Routledge. pp. 275–291. ISBN 978-0415955058.

- Enright, Robert. "Two Weaknesses of Forgiving: it victimizes and it stops justice". Psychology Today. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Marsh, Jason. "Is Vengeance Better For Victims, than Forgiveness?". Greater Good. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Luskin, Fred. "Forgiveness is not what you think it is". Curable Health. Laura Seago. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Zaibert, Loe (2009). "The Paradox of Forgiveness" (PDF). Journal of Moral Philosophy. 6 (3): 365–393. doi:10.1163/174552409X433436. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- North, Joanna (1998). Exploring Forgiveness (1998). University of Wisconsin. p. 17. ISBN 0299157741.

- Seltzer, Leon. "Fake vs. True Forgiveness". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Worthington, Everett (February 1, 2001). "Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience" (PDF). Psychology & Health. 19 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1080/0887044042000196674. S2CID 10052021. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Worthington, Everett (2000). "Forgiving Usually Takes Time: A Lesson Learned by Studying Interventions to Promote Forgiveness". Journal of Psychology and Theology. 28: 3–20. doi:10.1177/009164710002800101. S2CID 146762070.

- Bedrick, David (2014-09-25). "6 reasons not to forgive, not yet". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- "Healing From Betrayal and Forgiving It". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- Escher, Daniel (2013). "How Does Religion Promote Forgiveness? Linking Beliefs, Orientations, and Practices". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 52 (1): 100–119. doi:10.1111/jssr.12012. ISSN 0021-8294. JSTOR 23353893.

- "JewFAQ discussion of forgiveness on Yom Kippur". 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-23. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

- "Covenant and Conversation" (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church 1864".

- "The Parable of the Prodigal Son in Christianity and Buddhism". 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Luke 23:34

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church 2447".

- "Matthew, CHAPTER 6 | USCCB". bible.usccb.org.

- Mark 11:25, Matthew 6:14–15

- "Charles E. Moore, Radical, Communal, Bearing Witness: The Church as God's Mission in Bruderhof Perspective and Practice". missiodeijournal.com. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- 1 John 2:2

- Ephesians 4:32

- Matthew 18:21–35

- Matthew 5:7

- Matthew 5:23–24

- Mark 11:25

- Luke 6:27–29

- Luke 6:36

- Luke 6:37

- Matthew 18:21–22

- "Apostolic Journey to Lebanon: Meeting with members of the government, institutions of the Republic, the diplomatic corps, religious leaders and representatives of the world of culture (May 25th Hall of the Baabda Presidential Palace, 15 September 2012) | BENEDICT XVI". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- "Pope at Audience: 'We are forgiven as we forgive others' - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. April 24, 2019.

- Abu-Nimer & Nasser (2013), "Forgiveness in The Arab and Islamic Contexts", Journal of Religious Ethics, 41(3), pp. 474–494

- Oliver Leaman (2005), The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415326391, pp. 213-216

- [Quran 5:95]

- Mohammad Hassan Khalil (2012), Islam and the Fate of Others: The Salvation Question, Oxford University Press, pp. 65–94, ISBN 978-0199796663

- [Quran 42:40]

- Shah, S. S. (1996), "Mercy Killing in Islam: Moral and Legal Issues", Arab Law Quarterly, 11(2), pp. 105–115.

- Amanullah, M. (2004), "Just Retribution (Qisas) Versus Forgiveness (‘Afw)", in Islam: Past, Present AND Future, pp. 871–883; International Seminar on Islamic Thoughts Proceedings, December 2004, Department of Theology and Philosophy, Faculty of Islamic Studies Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

- Gottesman, E. (1991), "Reemergence of Qisas and Diyat in Pakistan, Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 23, pp. 433–439

- Tsang, J. A., McCullough, M. E., & Hoyt, W. T. (2005). "Psychometric and Rationalization Accounts of the Religion-Forgiveness Discrepancy", Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), pp. 785–805.

- Khalil Athamina (1992), "Al-Qisas: its emergence, religious origin and its socio-political impact on early Muslim society", Studia Islamica, pp. 53–74

- "Psychjourney – Introduction to Buddhism Series". 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-04-14. Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- "Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery - Universal Loving Kindness". 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Spirit of Vatican II: Buddhism – Buddhism and Forgiveness". 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery - Preparing for Death". 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-01-18. Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- Accesstoinsight.org Archived 2009-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, translation by Thanissaro Bikkhu

- Holi Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine India Heritage (2009)

- Agarwal, R. (2013), "Water Festivals of Thailand: The Indian Connection" Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. Silpakorn University, Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts, pp. 7-18

- Hinduism Archived 2013-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, see section on Sacred times and festivals, Encyclopædia Britannica (2009)

- "Bali - The day of silence" Archived 2009-01-31 at the Wayback Machine Indonesia (2010)

- See entry for Forgiveness Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine, English-Sanskrit Dictionary, Spoken Sanskrit, Germany (2010)

- Michael E. McCullough, Kenneth I. Pargament, Carl E. Thoresen (2001), Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice, The Guildford Press, ISBN 978-1572307117, pp. 21–39

- Ralph Griffith (Transl.), The Hymns of RugVeda, Motilal Banarsidas (1973)

- Hunter, Alan (2007), "Forgiveness: Hindu and Western Perspectives", Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 20(1), 11

- Ransley, Cynthia (2004), Forgiveness: Themes and issues. Forgiveness and the healing process: A central therapeutic concern, ISBN 1-58391-182-0, Brunner-Routledge, pp. 10–32

- See Manusamhita, 11.55, Mahabharata Vol II, 1022:8

- Prafulla Mohapatra (2008), Ethics and Society, Concept Publishing, ISBN 978-8180695230, pp. 22–25

- Temoshok and Chandra, Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice, The Guildford Press, ISBN 978-1572307117, see Chapter 3

- Radhakrishnan (1995), Religion and Society, Indus, Harper Collins India

- Sinha (1985), Indian psychology, Vol 2, Emotion and Will, Motilal Banarsidas, New Delhi

- Vana Parva Archived 2013-03-27 at the Wayback Machine, see Section XXIX; Gutenberg Archives Mahabharata Vol I (Kisari Mohan Ganguli 1896); Produced by John B. Hare, David King, and David Widger

- Udyoga Parva Archived 2013-10-12 at the Wayback Machine see page 61–62, Mahabharata, Translated by Sri Kisari Mohan Ganguli

- Ashtavakra Gita, Chapter 1, Verse 2 Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Translated by OSHO (2008)

- Original: मुक्तिं इच्छसि चेत्तात विषयान् विषवत्त्यज । क्षमार्जवदयातोषसत्यं पीयूषवद् भज || 2 ||

- Ashtavakra Gita has over 10 translations, each different; the above is closest consensus version

- Mukerjee, Radhakaml (1971), Aṣṭāvakragītā (the Song of the Self Supreme): The Classical Text of Ātmādvaita by Aṣṭāvakra, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-81-208-1367-0

- Varni, Jinendra; Ed. Prof. Sagarmal Jain, Translated Justice T.K. Tukol and Dr. K.K. Dixit (1993). Samaṇ Suttaṁ. New Delhi: Bhagwan Mahavir memorial Samiti. verse 84

- Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6. p. 285

- Chapple. C.K. (2006) Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life Delhi:Motilal Banarasidas Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2045-6 p.46

- Hastings, James (2003), Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 10, Kessinger Publishing ISBN 978-0-7661-3682-3 p.876

- Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6. p.18 and 224

- Translated from Prakrit by Nagin J. shah and Madhu Sen (1993) Concept of Pratikramana Ahmedabad: Gujarat Vidyapith pp.25–26

-

- Jacobi, Hermann (1895). F. Max Müller (ed.). The Uttarādhyayana Sūtra. Sacred Books of the East vol.45, Part 2. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1538-1. Archived from the original on 2009-07-04. Note: ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1895 reprint.

-

- Jacobi, Hermann (1884). F. Max Müller (ed.). The Kalpa Sūtra. Sacred Books of the East vol.22, Part 1. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1538-1. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Note: ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint. URL is the scan version of the original 1884 reprint.

- Gorsuch, R. L.; Hao, J. Y. (1993). "Forgiveness: An exploratory factor analysis and its relationship to religious variables". Review of Religious Research. 34 (4): 351–363. doi:10.2307/3511971. JSTOR 3511971. Archived from the original on 2004-09-21.

- "About Breaking the Cycle, A project of the Bruderhof". www.breakingthecycle.com. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- "The key to forgiveness is the refusal to seek revenge". The Guardian. 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved Feb 21, 2013.

- "Beyond Right & Wrong: Stories of Justice and Forgiveness". Forgiveness Project. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Newberry, Paul A. (April 2001). "Joseph Butler on Forgiveness: A Presupposed Theory of Emotion". Journal of the History of Ideas. 62 (2): 233–244. doi:10.2307/3654356. JSTOR 3654356.

- Fincham, F., Hall, J., & Beach, S. (2006). Forgiveness In Marriage: Current Status And Future Directions. Family Relations, 415–427.

- Fow, Neil Robert (1996). "The Phenomenology of Forgiveness and Reconciliation". Journal of Phenomenological Psychology. 27 (2): 219–233. doi:10.1163/156916296X00113.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Ed Diener1; Martin E.P. Seligman (2002-01-01). "Very Happy People". Psychological Science. 13 (1): 81–84. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00415. PMID 11894851. S2CID 371807.

- Yi Xie; Siqing Peng (July 2009). "How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness". Psychology & Marketing. 26 (7): 572–589. doi:10.1002/mar.20289.

- Witvliet, Charlotte van Oyen; Ludwig, Thomas E.; Laan, Kelly L. Vander (2001-03-01). "Granting Forgiveness or Harboring Grudges: Implications for Emotion, Physiology, and Health". Psychological Science. 12 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00320. PMID 11340919. S2CID 473643.

- "PsycNET". psycnet.apa.org.

- Wade, Nathaniel G.; Johnson, Chad V.; Meyer, Julia E. (2008-01-01). "Understanding concerns about interventions to promote forgiveness: A review of the literature". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 45 (1): 88–102. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.1.88. PMID 22122367.

- Wade, Nathaniel G.; Bailey, Donna C.; Shaffer, Philip (2005). "Helping Clients Heal: Does Forgiveness Make a Difference?". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 36 (6): 634–641. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.36.6.634.

- Lambert, Nathaniel (2010). "Motivating Change in Relationships: Can Prayer Increase Forgiveness?". Psychological Science. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. 21 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1177/0956797609355634. JSTOR 41062174. PMID 20424033. S2CID 20228955.

- Luskin, Fred (January 21, 2013). Forgive For Good. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0062517210.

- Stover, C. S. (1 April 2005). "Domestic Violence Research: What Have We Learned and Where Do We Go From Here?". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 20 (4): 448–454. doi:10.1177/0886260504267755. PMID 15722500. S2CID 22219265.

- López, Javier; Serrano, Maria Inés; Giménez, Isabel; Noriega, Cristina (January 2021). "Forgiveness Interventions for Older Adults: A Review". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (9): 1866. doi:10.3390/jcm10091866. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 8123510. PMID 33925790.

- Wuthnow, Robert (2000-01-01). "How Religious Groups Promote Forgiving: A National Study". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 39 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1111/0021-8294.00011.

- Webb, Jon R.; Phillips, T. Dustin; Bumgarner, David; Conway-Williams, Elizabeth (2012-06-22). "Forgiveness, Mindfulness, and Health". Mindfulness. 4 (3): 235–245. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0119-0. ISSN 1868-8527. S2CID 144214249.

- Ingersoll-Dayton, Berit; Krause, Neal (2005-05-01). "Self-Forgiveness A Component of Mental Health in Later Life". Research on Aging. 27 (3): 267–289. doi:10.1177/0164027504274122. ISSN 0164-0275. S2CID 210225071.

- Hook, Joshua N.; Farrell, Jennifer E.; Davis, Don E.; Tongeren, Daryl R. Van; Griffin, Brandon J.; Grubbs, Joshua; Penberthy, J. Kim; Bedics, Jamie D. (2015-01-02). "Self-Forgiveness and Hypersexual Behavior". Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 22 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1080/10720162.2014.1001542. ISSN 1072-0162. S2CID 145006916.

- Wohl, Michael J. A.; Pychyl, Timothy A.; Bennett, Shannon H. (2010-01-01). "I forgive myself, now I can study: How self-forgiveness for procrastinating can reduce future procrastination". Personality and Individual Differences. 48 (7): 803–808. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.029.

- Weir, Kirsten (January 2017). "Forgiveness can improve mental and physical health".

- Raj, Paul; Elizabeth, C.S.; Padmakumari, P. (2016-12-31). Walla, Peter (ed.). "Mental health through forgiveness: Exploring the roots and benefits". Cogent Psychology. 3 (1): 1153817. doi:10.1080/23311908.2016.1153817. ISSN 2331-1908. S2CID 73654630.

- McCullough, Michael, and Charlotte Vanoyen. "The Psychology of Forgiveness." Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2002.

- Berry, Jack W.; Everett, L. Jr. Worthington (2001). "Forgivingness, Relationship Quality, Stress While Imagining Relationship Events, and Physical and Mental Health". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 48 (4): 447–55. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.4.447.

- Worthington, Everett L.; Scherer, Michael (2004). "Forgiveness Is an Emotion-focused Coping Strategy That Can Reduce Health Risks and Promote Health Resilience: Theory, Review, and Hypotheses". Psychology & Health. 19 (3): 385–405. doi:10.1080/0887044042000196674. S2CID 10052021.

- Wilson, T.; Milosevic, A.; Carroll, M.; Hart, K.; Hibbard, S. (2008). "Physical Health Status in Relation to Self-Forgiveness and Other-Forgiveness in Healthy College Students". Journal of Health Psychology. 13 (6): 798–803. doi:10.1177/1359105308093863. PMID 18697892. S2CID 24569507.

- Mayo Clinic Staff (13 November 2020). "Forgiveness; Letting go of grudges and bitterness". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - McCullough, Michael E., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Carl E. Thoresen. Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford Press, 2000.

- vanOyen Witvliet, Charlotte; Ludwig, Thomas E.; Laan, Kelly L. Vander (2001). "Granting Forgiveness or Harboring Grudges: Implications for Emotion, Physiology, and Health". Psychological Science. 12 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00320. ISSN 0956-7976. JSTOR 40063597. PMID 11340919. S2CID 473643.

- Gamlund, Espen. "Ethical aspects of self-forgiveness". Sats. 15. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- Szablowinski, ZENON (2011-01-01). "Self-forgiveness and forgiveness". The Heythrop Journal. 53 (4): 678–689. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2010.00611.x.

- Jung, Minjee; Park, Yeonsoo; Baik, Seung Yeon; Kim, Cho Long; Kim, Hyang Sook; Lee, Seung-Hwan (February 2019). "Self-Forgiveness Moderates the Effects of Depression on Suicidality". Psychiatry Investigation. 16 (2): 121–129. doi:10.30773/pi.2018.11.12.1. ISSN 1738-3684. PMC 6393745. PMID 30808118.

- Fisher, M. L.; Exline, J. J. (2010). "Moving toward self-forgiveness: Removing barriers related to shame, guilt, and regret". Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 4 (8): 548–558. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00276.x.