Demotic (Egyptian)

Demotic (from Ancient Greek: δημοτικός dēmotikós, 'popular') is the ancient Egyptian script derived from northern forms of hieratic used in the Nile Delta, and the stage of the Egyptian language written in this script, following Late Egyptian and preceding Coptic. The term was first used by the Greek historian Herodotus to distinguish it from hieratic and hieroglyphic scripts. By convention, the word "Demotic" is capitalized in order to distinguish it from demotic Greek.

| Demotic | |

|---|---|

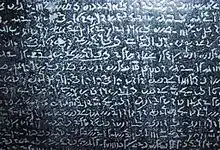

Demotic script on a replica of the Rosetta Stone | |

| Script type | Logographic

|

Time period | c. 650 BC–5th century AD |

| Direction | Mixed |

| Languages | Demotic (Egyptian language) |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems |

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Egyd (070), Egyptian demotic |

Script

The Demotic script was referred to by the Egyptians as sš/sẖ n šꜥ.t, "document writing," which the second-century scholar Clement of Alexandria called ἐπιστολογραφική, "letter-writing," while early Western scholars, notably Thomas Young, formerly referred to it as "Enchorial Egyptian." The script was used for more than a thousand years, and during that time a number of developmental stages occurred. It is written and read from right to left, while earlier hieroglyphs could be written from top to bottom, left to right, or right to left. Parts of the Demotic Greek Magical Papyri were written with a cypher script.[1]

Early Demotic

Early Demotic (often referred to by the German term Frühdemotisch) developed in Lower Egypt during the later part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, particularly found on steles from the Serapeum of Saqqara. It is generally dated between 650 and 400 BC, as most texts written in Early Demotic are dated to the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and the subsequent rule as a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire, which was known as the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. After the reunification of Egypt under Psamtik I, Demotic replaced Abnormal Hieratic in Upper Egypt, particularly during the reign of Amasis II, when it became the official administrative and legal script. During this period, Demotic was used only for administrative, legal, and commercial texts, while hieroglyphs and hieratic were reserved for religious texts and literature.

Middle (Ptolemaic) Demotic

Middle Demotic (c. 400–30 BC) is the stage of writing used during the Ptolemaic Kingdom. From the 4th century BC onwards, Demotic held a higher status, as may be seen from its increasing use for literary and religious texts. By the end of the 3rd century BC, Koine Greek was more important, as it was the administrative language of the country; Demotic contracts lost most of their legal force unless there was a note in Greek of being registered with the authorities.

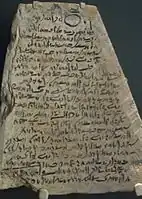

Ostracon with Demotic inscription. Ptolemaic Kingdom, c. 305–30 BC. Probably from Thebes. It is a prayer to the god Amun to heal a man's blindness.

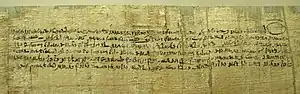

Ostracon with Demotic inscription. Ptolemaic Kingdom, c. 305–30 BC. Probably from Thebes. It is a prayer to the god Amun to heal a man's blindness. Contract in Demotic writing, with signature of a witness on the verso. Papyrus, Ptolemaic era.

Contract in Demotic writing, with signature of a witness on the verso. Papyrus, Ptolemaic era.

Late (Roman) Demotic

From the beginning of Roman rule of Egypt, Demotic was progressively less used in public life. There are, however, a number of literary texts written in Late Demotic (c. 30 BC – 452 AD), especially from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, though the quantity of all Demotic texts decreased rapidly towards the end of the second century. In contrast to the way Latin eliminated languages in the western part of the Empire, Greek did not replace Demotic entirely.[2] After that, Demotic was only used for a few ostraca, subscriptions to Greek texts, mummy labels, and graffiti. The last dated example of the Demotic script is a graffito on the walls of the temple of Isis at Philae, dated to December 12, 452. The text simply reads "Petise, son of Petosiris"; who Petise was is unknown.[3]

Uniliteral signs and transliteration

Like its hieroglyphic predecessor script, Demotic possessed a set of "uniliteral" or "alphabetical" signs that could be used to represent individual phonemes. These are the most common signs in Demotic, making up between one third and one half of all signs in any given text; foreign words are also almost exclusively written with these signs.[4] Later (Roman Period) texts used these signs even more frequently.[5]

The table below gives a list of such uniliteral signs along with their conventional transcription, their hieroglyphic origin, the Coptic letters derived from them, and notes on usage.[4][5][6]

| Transliteration | Sign | Hieroglyphic origin[6] | Coptic descendant | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ꜣ | Mostly used word-initially, only rarely word-finally. | |||||||

| Never used word-initially. | ||||||||

| ı͗ | ⲳ[lower-alpha 1] | Only used word-initially. | ||||||

| e | Marks a prothetic ı͗ or word-internal e. | |||||||

| ꜥ | ⲵ[lower-alpha 1] | Usually used when not stacked above or below another sign. | ||||||

| Usually used when stacked under a horizontal sign. | ||||||||

| Usually used when stacked on top of a horizontal sign. | ||||||||

| y | ||||||||

| w | Used word-medially and word-finally. | |||||||

| Used word-initially; consonantal. | ||||||||

| Used when w is a plural marker or the 3rd person plural suffix pronoun. | ||||||||

| b | Used interchangeably. | |||||||

| p | The first form developed from the second and largely supplanted it. | |||||||

| f | ϥ | |||||||

| m | Used interchangeably. The second form developed from the first. | |||||||

| n | Usually used when not stacked above or below another sign, but never for the preposition n or the genitive particle n. | |||||||

| ⲻ[lower-alpha 1] | Usually used when stacked above or below another sign. | |||||||

| r | The normal form of r when it is retained as a consonant and not lost to sound change. | |||||||

| Used interchangeably to indicate a vowel corresponding to Coptic ⲉ, sometimes resulting from a loss of a consonant such as in the preposition r; also used for prothetic ı͗. | ||||||||

| l | ||||||||

| h | ⳏ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||

| ḥ | ⳕ[lower-alpha 1] | Used interchangeably. | ||||||

| ϩ, ⳍ[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

| ḫ | ⳓ[lower-alpha 1], ⳋ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||

| h̭ | ||||||||

| ẖ | ϧ | Usually used when not stacked above or below another sign. | ||||||

| Usually used when stacked above or below another sign. | ||||||||

| s | Most common form when not stacked above or below another sign. | |||||||

| Used often in names and Greek loanwords. Never used word-initially in native Egyptian words. | ||||||||

| Usually used when stacked under a horizontal sign. | ||||||||

| Usually used when stacked on top of a horizontal sign. | ||||||||

| Used as a pronoun. | ||||||||

| š | ϣ, ⳅ[lower-alpha 1] | Usually used when not stacked above or below another sign. The second form developed from the first. | ||||||

| ⳇ[lower-alpha 1] | Used when stacked above or below another sign. | |||||||

| q | ⲹ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||

| k | ϭ | Often written below the line. | ||||||

| Originally biliteral for kꜣ. In late texts often used as q. | ||||||||

| g | ⳛ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||

| t | ||||||||

| ϯ[lower-alpha 2] | Less common, except as the verb ḏj ‘to give’. | |||||||

| d | ||||||||

| ṱ | Used interchangeably. Marks a word-final t which is actually pronounced, distinguished from the silent t of the feminine suffix. | |||||||

| ṯ | Originally the writing of the verb ṯꜣj ‘to take’, sometimes used as a phonogram. | |||||||

| ḏ | ⳙ[lower-alpha 1] | Used interchangeably. The cobra form is rare. | ||||||

| ϫ, ⳗ[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

- Only found in Old Coptic texts.

- Alternatively, ϯ may be a ligature of ⲧ and ⲓ.[7]

Language

| Demotic | |

|---|---|

| sš n šꜥ.t ("document writing") | |

| Region | Ancient Egypt |

| Era | c. 450 BC to 450 AD, when it was replaced in writing with Coptic |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms | Archaic Egyptian

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Demotic is a development of the Late Egyptian language and shares much with the later Coptic phase of the Egyptian language. In the earlier stages of Demotic, such as those texts written in the Early Demotic script, it probably represented the spoken idiom of the time. But, as it was increasingly used for only literary and religious purposes, the written language diverged more and more from the spoken form, leading to significant diglossia between the Late Demotic texts and the spoken language of the time, similar to the use of classical Middle Egyptian during the Ptolemaic Period.

Phonology

The most important source of information about Demotic phonology is Coptic. The consonant inventory of Demotic can be reconstructed on the basis of evidence from the Coptic dialects.[8] Demotic orthography is relatively opaque. The Demotic “alphabetical” signs are mostly inherited from the hieroglyphic script, and due to historical sound changes they do not always map neatly onto Demotic phonemes. However, the Demotic script does feature certain orthographic innovations, such as the use of the sign h̭ for /ç/,[9] which allow it to represent sounds that were not present in earlier forms of Egyptian.

The Demotic consonants can be divided into two primary classes: obstruents (stops, affricates and fricatives) and sonorants (approximants, nasals, and semivowels).[10] Voice is not a contrastive feature; all obstruents are voiceless and all sonorants are voiced.[11] Stops may be either aspirated or tenuis (unaspirated),[12] although there is evidence that aspirates merged with their tenuis counterparts in certain environments.[13]

The following table presents the consonants of Demotic Egyptian. The reconstructed value of a phoneme is given in IPA transcription, followed by a transliteration of the corresponding Demotic “alphabetical” sign(s) in angle brackets ⟨ ⟩.

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalv. | Palatal | Velar | Pharyng. | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | /m/ | /n/ | |||||||

| Obstruent | aspirate | /pʰ/ ⟨p⟩ | /tʰ/ ⟨t ṯ⟩ | /t͡ʃʰ/ ⟨ṯ⟩ | /cʰ/ ⟨k⟩ | /kʰ/ ⟨k⟩ | |||

| tenuis | /t/ ⟨d ḏ t ṯ ṱ⟩ | /t͡ʃ/ ⟨ḏ ṯ⟩ | /c/ ⟨g k q⟩ | /k/ ⟨q k g⟩ | |||||

| fricative | /f/ ⟨f⟩ | /s/ ⟨s⟩ | /ʃ/ ⟨š⟩ | /ç/ ⟨h̭ ḫ⟩ | /x/ ⟨ẖ ḫ⟩ | /ħ/ ⟨ḥ⟩ | /h/ ⟨h⟩ | ||

| Approximant | /v/ ⟨v⟩ | /r/ ⟨r⟩ | /l/ ⟨l r⟩ | /j/ ⟨y ı͗⟩ | /w/ ⟨w⟩ | /ʕ/ ⟨ꜥ⟩[lower-alpha 1] | |||

- /ʕ/ was lost near the end of the Ptolemaic period.[14]

| Demotic spelling | Demotic phoneme | Coptic reflexes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | FMSL | A | P | ||

| m | */m/ | ⲙ /m/ | |||

| n | */n/ | ⲛ /n/ | |||

| p | */pʰ/ | ⲫ /pʰ/ | ⲡ /p/ | ||

| t, ṯ | */tʰ/ | ⲑ /tʰ/ | ⲧ /t/ | ||

| ṯ | */t͡ʃʰ/ | ϭ /t͡ʃʰ/ | ϫ /t͡ʃ/ | ||

| k | */cʰ/ | ϭ /t͡ʃʰ/ | ϭ /c/ | ||

| k | */kʰ/ | ⲭ /kʰ/ | ⲕ /k/ | ||

| p | *[p][lower-alpha 1] | ⲡ /p/ | |||

| d, ḏ, t, ṯ, ṱ | */t/ | ⲧ /t/ | |||

| ḏ | */t͡ʃ/ | ϫ /t͡ʃ/ | |||

| g, k, q | */c/ | ϫ /t͡ʃ/ | ϭ /c/ | ⲕ /c/ | |

| q, k, g | */k/ | ⲕ /k/ | ⲹ /k/ | ||

| f | */f/ | ϥ /f/ | |||

| s | */s/ | ⲥ /s/ | |||

| š | */ʃ/ | ϣ /ʃ/ | |||

| h̭, ḫ | */ç/ | ϣ /ʃ/ | ⳉ /x/ | ⳋ /ç/ | |

| ẖ, ḫ | */x/ | ϧ /x/ | ϩ /h/ | ⳉ /x/ | ϧ /x/ |

| ḥ | */ħ/ | ϩ /h/ | |||

| h | */h/ | ϩ /h/ | |||

| b | */v/ | ⲃ /v/ | |||

| r | */r/ | ⲣ /l/[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| l, r | */l/ | ⲗ /l/ | |||

| y, ı͗ | */j/ | ⲉⲓ /j/ | |||

| w | */w/ | ⲟⲩ /w/ | |||

| ꜥ | */ʕ/ | ∅ | |||

- [p] is an allophone of /pʰ/ in Demotic.

- ⲗ~ⲣ in Fayyumic

Decipherment

The Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799. It is inscribed with three scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic, and the Greek alphabet. There are 32 lines of Demotic, which is the middle of the three scripts on the stone. The Demotic was deciphered before the hieroglyphs, starting with the efforts of Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy. Scholars were eventually able to translate the hieroglyphs by comparing them with the Greek words, which could be readily translated, and fortifying that process by applying knowledge of Coptic (the Coptic language being descended from earlier forms of Egyptian represented in hieroglyphic writing). Egyptologists, linguists and papyrologists who specialize in the study of the Demotic stage of Egyptian script are known as Demotists.

See also

- Transliteration of Ancient Egyptian

Notes

- Hans Dieter Betz (1992). The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells, Volume 1.

- Haywood, John (2000). Historical atlas of the classical world, 500 BC–AD 600. Barnes & Noble Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7607-1973-2.

However, Greek did not take over as completely as Latin did in the west and there remained large communities of Demotic...and Aramaic speakers

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene (2018). "The Last Demotic Inscription". In Donker van Heel, Koenraad; Hoogendijk, Francisca A. J.; Marin, Cary J. (eds.). Hieratic, Demotic, and Greek Studies and Text Editions: Of Making Many Books There Is No End. Festschrift in Honour of Sven P. Vleeming. Leiden. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-9-0043-4571-3.

- Clarysse, Willy (1994) Demotic for Papyrologists: A First Acquaintance, pages 96–98.

- Johnson, Janet H. (1986). Thus Wrote ꜥOnchsheshonqy: An Introductory Grammar of Demotic. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, No. 45. Chicago: The Oriental Institute. pp. 2–4.

- The Demotic Palaeographical Database Project, accessed 11 November 2020.

- Quack (2017). "How the Coptic Script Came About". Greek Influence on Egyptian-Coptic: Contact-Induced Change in an Ancient African Language. Widmaier Verlag. p. 75.

It has normally been claimed that it derives from the form of the infinitive ti in Demotic, but the actual forms do not fit well; and furthermore it is a point of some concern that this sign never turns up in any ‘Old Coptic’ text (where we always have ⲧⲓ for this sound sequence). For this reason the proposal by Kasser that it is actually a ligature of t and i seems to me quite convincing.

- Allen, James P. (2020). Ancient Egyptian Phonology. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. doi:10.1017/9781108751827. ISBN 9781108751827. S2CID 216256704.

Most of the Demotic consonants have straightforward correspondents in Coptic and can therefore be presumed to have had the same values they do in Coptic.

- Allen, James P. (2020). Ancient Egyptian Phonology. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. doi:10.1017/9781108751827. ISBN 9781108751827. S2CID 216256704.

The grapheme h̭ appears in words for which Coptic has /x̱/, such as h̭ꜥr “skin” > A ⳉⲁⲁⲣⲉ, B ϣⲁⲣ, F ϣⲉⲉⲗ, L ϣⲁⲣⲉ, M ϣⲉⲣ, S ϣⲁⲁⲣ.

- Depuydt, Leo (1993). "On Coptic Sounds" (PDF). Orientalia. Gregorian Biblical Press. 62 (4): 338–375.

- Allen, James P. (2020). Ancient Egyptian Phonology. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. doi:10.1017/9781108751827. ISBN 9781108751827. S2CID 216256704.

Voice is not a phonemic feature of the consonantal system in any stage of the language.

- Allen, James P. (2020). Ancient Egyptian Phonology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–75. doi:10.1017/9781108751827. ISBN 9781108751827. S2CID 216256704.

The primary phonemic distinctions between the consonants in all stages of Egyptian are two, aspiration and palatalization...Aspiration remains a primary distinction throughout the history of the language.

- Peust, Carsten (1999). Egyptian Phonology: An Introduction to the Phonology of a Dead Language. Peust und Gutschmidt. p. 85. doi:10.11588/diglit.1167.

After the New Kingdom, confusion between both series of stops becomes very frequent in Egyptian writing. A phonetic merger of some kind is certainly the cause of this phenomenon.

- Peust, Carsten (1999). Egyptian Phonology: An Introduction to the Phonology of a Dead Language. Peust und Gutschmidt. p. 102. doi:10.11588/diglit.1167.

In Roman Demotic ⟨ꜥ⟩ suddenly begins to be employed in a very inconsistent manner. It is often omitted or added without etymological justification. I take this as an indication that the phoneme /ʕ/ was lost from the spoken language.

References

- Betrò, Maria Carmela (1996). Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt. New York; Milan: Abbeville Press (English); Arnoldo Mondadori (Italian). pp. 34–239. ISBN 978-0-7892-0232-1.

- Depauw, Mark (1997). A Companion to Demotic Studies. Papyrologica Bruxellensia, No. 28. Bruxelles: Fondation égyptologique reine Élisabeth.

- Johnson, Janet H. (1986). Thus Wrote ꜥOnchsheshonqy: An Introductory Grammar of Demotic. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, No. 45. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

External links

- Demotic and Abnormal Hieratic Texts

- List of all Demotic texts in Trismegistos

- Chicago Demotic Dictionary

- The American Society of Papyrologists

- Directory of Institutions and Scholars Involved in Demotic Studies

- Demotic Texts on the Internet

- Thus Wrote 'Onchsheshonqy: An Introductory Grammar of Demotic by Janet H. Johnson

- Demotische Grammatik by Wilhelm Spiegelberg (in German)

- Hieratic/Demotic Fonts