Gothic alphabet

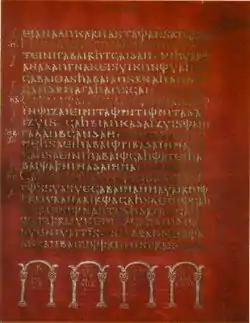

The Gothic alphabet is an alphabet used for writing the Gothic language. Ulfilas (or Wulfila) developed it in the 4th century AD for the purpose of translating the Bible.[1]

| Gothic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | From c. 350, in decline by 600 |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Gothic |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Goth (206), Gothic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Gothic |

Unicode range | U+10330–U+1034F |

The alphabet essentially uses uncial forms of the Greek alphabet, with a few additional letters to express Gothic phonology:

Origin

Ulfilas is thought to have consciously chosen to avoid the use of the older Runic alphabet for this purpose, as it was heavily connected with pagan beliefs and customs.[2] Also, the Greek-based script probably helped to integrate the Gothic nation into the dominant Greco-Roman culture around the Black Sea.[3]

Letters

Below is a table of the Gothic alphabet.[4] Two letters used in its transliteration are not used in current English: thorn þ (representing /θ/), and hwair ƕ (representing /hʷ/).

As with the Greek alphabet, Gothic letters were also assigned numerical values. When used as numerals, letters were written either between two dots (•𐌹𐌱• = 12) or with an overline (𐌹𐌱 = 12). Two letters, 𐍁 (90) and 𐍊 (900), have no phonetic value.

The letter names are recorded in a 9th-century manuscript of Alcuin (Codex Vindobonensis 795). Most of them seem to be Gothic forms of names also appearing in the rune poems. The names are given in their attested forms followed by the reconstructed Gothic forms and their meanings.[5]

| Letter | Translit. | Compare | Gothic name | PGmc rune name | IPA | Numeric value | XML entity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐌰 | a | Α | aza < *ans "god" or asks "ash" | *ansuz | /a, aː/ | 1 | 𐌰 | |

| 𐌱 | b | Β | bercna < *bairka "birch" | *berkanan | /b/ [b, β] | 2 | 𐌱 | |

| 𐌲 | g | Γ | geuua < giba "gift" | *gebō | /ɡ/ [ɡ, ɣ, x]; /n/ [ŋ] | 3 | 𐌲 | |

| 𐌳 | d | Δ, D | daaz < dags "day" | *dagaz | /d/ [d, ð] | 4 | 𐌳 | |

| 𐌴 | e | Ε | eyz < aiƕs "horse" or eiws "yew" | *eihwaz, *ehwaz | /eː/ | 5 | 𐌴 | |

| 𐌵 | q | quetra < *qairþra ? or qairna "millstone" | (see *perþō) | /kʷ/ | 6 | 𐌵 | ||

| 𐌶 | z | Ζ | ezec < (?)[6] | *algiz | /z/ | 7 | 𐌶 | |

| 𐌷 | h | Η | haal < *hagal or *hagls "hail" | *haglaz | /h/, /x/ | 8 | 𐌷 | |

| 𐌸 | þ (th) | Φ, Ψ | thyth < þiuþ "good" or þaurnus "thorn" | *thurisaz | /θ/ | 9 | 𐌸 | |

| 𐌹 | i | Ι | iiz < *eis "ice" | *īsaz | /i/ | 10 | 𐌹 | |

| 𐌺 | k | Κ | chozma < *kusma or kōnja "pine sap" | *kaunan | /k/ | 20 | 𐌺 | |

| 𐌻 | l | Λ | laaz < *lagus "sea, lake" | *laguz | /l/ | 30 | 𐌻 | |

| 𐌼 | m | Μ | manna < manna "man" | *mannaz | /m/ | 40 | 𐌼 | |

| 𐌽 | n | Ν | noicz < nauþs "need" | *naudiz | /n/ | 50 | 𐌽 | |

| 𐌾 | j | G, ᛃ | gaar < jēr "year" | *jēran | /j/ | 60 | 𐌾 | |

| 𐌿 | u | ᚢ | uraz < *ūrus "aurochs" | *ūruz | /ʊ/, /uː/ | 70 | 𐌿 | |

| 𐍀 | p | Π | pertra < *pairþa ? | *perþō | /p/ | 80 | 𐍀 | |

| 𐍁 | Ϙ | 90 | 𐍁 | |||||

| 𐍂 | r | R | reda < *raida "wagon" | *raidō | /r/ | 100 | 𐍂 | |

| 𐍃 | s | S | sugil < sauil or sōjil "sun" | *sôwilô | /s/ | 200 | 𐍃 | |

| 𐍄 | t | Τ, ᛏ | tyz < *tius "the god Týr" | *tīwaz | /t/ | 300 | 𐍄 | |

| 𐍅 | w | Υ | uuinne < winja "field, pasture" or winna "pain" | *wunjō | /w/, /y/ | 400 | 𐍅 | |

| 𐍆 | f | Ϝ, F | fe < faihu "cattle, wealth" | *fehu | /ɸ/ | 500 | 𐍆 | |

| 𐍇 | x | Χ | enguz < *iggus or *iggws "the god Yngvi" | *ingwaz | /k/[7] | 600 | 𐍇 | |

| 𐍈 | ƕ (hw) | Θ | uuaer < *hwair "kettle" | /hʷ/, /ʍ/ | 700 | 𐍈 | ||

| 𐍉 | o | Ω, Ο, ᛟ | utal < *ōþal "ancestral land" | *ōþala | /oː/ | 800 | 𐍉 | |

| 𐍊 | ᛏ, Ͳ (Ϡ) | 900 | 𐍊 | |||||

Most of the letters have been taken over directly from the Greek alphabet, though a few have been created or modified from Latin and possibly (more controversially[8]) Runic letters to express unique phonological features of Gothic. These are:

- 𐌵 (q; derived either from a form of Greek stigma/digamma (

),[8] or from a cursive variant of kappa (ϰ), which could strongly resemble a u,[8] or by inverting Greek pi (𐍀) /p/, perhaps due to similarity in the Gothic names: pairþa versus qairþa)

),[8] or from a cursive variant of kappa (ϰ), which could strongly resemble a u,[8] or by inverting Greek pi (𐍀) /p/, perhaps due to similarity in the Gothic names: pairþa versus qairþa) - 𐌸 (þ; derived either from Greek phi (Φ) /f/ or psi (Ψ) /ps/ with phonetic reassignment, or Runic ᚦ)[9]

- 𐌾 (j; derived from Latin G /ɡ/[8])

- 𐌿 (u; possibly an allograph of Greek Ο (cf. the numerical values), or from Runic ᚢ /u/)[10]

- 𐍈 (ƕ; derived from Greek Θ /θ/ with phonetic reassignment; possibly the letterform was switched with 𐌸)[8]

- 𐍉 (o; derived either from Greek Ω or from Runic ᛟ,[11] or from a cursive form of Greek Ο, as such a form was more common for omicron than for omega in this time period, and as the sound values of omicron and omega had already merged by this time.[8])

𐍂 (r), 𐍃 (s) and 𐍆 (f) appear to be derived from their Latin equivalents rather than from the Greek, although the equivalent Runic letters (ᚱ, ᛋ and ᚠ), assumed to have been part of the Gothic futhark, possibly played some role in this choice.[12] However, Snædal claims that "Wulfila's knowledge of runes was questionable to say the least", as the paucity of inscriptions attests that knowledge and use of runes was rare among the East Germanic peoples.[8] Some variants of 𐍃 (s) are shaped like a sigma and more obviously derive from the Greek Σ.[8]

𐍇 (x) is only used in proper names and loanwords containing Greek Χ (xristus "Christ", galiugaxristus "Pseudo-Christ", zaxarias "Zacharias", aiwxaristia "eucharist").[13]

Regarding the letters' numeric values, most correspond to those of the Greek numerals. Gothic 𐌵 takes the place of Ϝ (6), 𐌾 takes the place of ξ (60), 𐌿 that of Ο (70), and 𐍈 that of ψ (700).

Diacritics and punctuation

Diacritics and punctuation used in the Codex Argenteus include a trema placed on 𐌹 i, transliterated as ï, in general applied to express diaeresis, the interpunct (·) and colon (:) as well as overlines to indicate sigla (such as xaus for xristaus) and numerals.

Unicode

The Gothic alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in March 2001 with the release of version 3.1.

The Unicode block for Gothic is U+10330– U+1034F in the Supplementary Multilingual Plane. As older software that uses UCS-2 (the predecessor of UTF-16) assumes that all Unicode codepoints can be expressed as 16 bit numbers (U+FFFF or lower, the Basic Multilingual Plane), problems may be encountered using the Gothic alphabet Unicode range and others outside of the Basic Multilingual Plane.

| Gothic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1033x | 𐌰 | 𐌱 | 𐌲 | 𐌳 | 𐌴 | 𐌵 | 𐌶 | 𐌷 | 𐌸 | 𐌹 | 𐌺 | 𐌻 | 𐌼 | 𐌽 | 𐌾 | 𐌿 |

| U+1034x | 𐍀 | 𐍁 | 𐍂 | 𐍃 | 𐍄 | 𐍅 | 𐍆 | 𐍇 | 𐍈 | 𐍉 | 𐍊 | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

- According to the testimony of the historians Philostorgius, Socrates of Constantinople and Sozomen. Cf. Streitberg (1910:20).

- Cf. Jensen (1969:474).

- Cf. Haarmann (1991:434).

- For a discussion of the Gothic alphabet see also Fausto Cercignani, The Elaboration of the Gothic Alphabet and Orthography, in "Indogermanische Forschungen", 93, 1988, pp. 168-185.

- The forms which are not attested in the Gothic corpus are marked with an asterisk. For a detailed discussion of the reconstructed forms, cf. Kirchhoff (1854). For a survey of the relevant literature, cf. Zacher (1855).

- Zacher arrives at *iuya, *iwja or *ius, cognate to ON ȳr, OE īw, ēow, OHG īwa "yew tree", though he admits having no ready explanation for the form ezec. Cf. Zacher (1855:10-13).

- Streitberg, p. 47

- Magnús Snædal (2015). "Gothic Contact with Latin" in Early Germanic Languages in Contact, Ed. John Ole Askedal and Hans Frede Nielsen.

- Cf. Mees (2002/2003:65).

- Cf. Kirchhoff (1854:55).

- Haarmann (1991:434).

- Cf. Kirchhoff (1854:55-56); Friesen (1915:306-310).

- Wright (1910:5).

See also

- Ring of Pietroassa

- Help:Gothic Unicode Fonts

References

- Braune, Wilhelm (1952). Gotische Grammatik. Halle: Max Niemeyer.

- Cercignani, Fausto, "The Elaboration of the Gothic Alphabet and Orthography", in Indogermanische Forschungen, 93, 1988, pp. 168–185.

- Dietrich, Franz (1862). Über die Aussprache des Gotischen Wärend der Zeit seines Bestehens. Marburg: N. G. Elwert'sche Universitätsbuchhandlung.

- Friesen, Otto von (1915). "Gotische Schrift" in Hoops, J. Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Bd. II. pp. 306–310. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.

- Haarmann, Harald (1991). Universalgeschichte der Schrift. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Jensen, Hans (1969). Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften.

- Kirchhoff, Adolf (1854). Das gothische Runenalphabet. Berlin: Wilhelm Hertz.

- Mees, Bernard (2002/2003). "Runo-Gothica: the runes and the origin of Wulfila's script", in Die Sprache, 43, pp. 55-79.

- Streitberg, Wilhelm (1910). Gotisches Elementarbuch. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- Weingärtner, Wilhelm (1858). Die Aussprache des Gotischen zur Zeit Ulfilas. Leipzig: T. O. Weigel.

- Wright, Joseph (1910). Grammar of the Gothic Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zacher, Julius (1855). Das gothische Alphabet Vulvilas und das Runenalphabet. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus.

External links

- Omniglot's Gothic writing page

- Pater Noster and Ave Maria in Gothic

- JavaScript Gothic transliterator

- Unicode code chart for Gothic

- WAZU JAPAN's Gallery of Gothic Unicode Fonts

- Dr. Pfeffer's Gothic Unicode Fonts

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with the Gothic range in a serif face.