Elgin Cathedral

Elgin Cathedral is a historic ruin in Elgin, Moray, north-east Scotland. The cathedral—dedicated to the Holy Trinity—was established in 1224 on land granted by King Alexander II outside the burgh of Elgin and close to the River Lossie. It replaced the cathedral at Spynie, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to the north, that was served by a small chapter of eight clerics. The new and bigger cathedral was staffed with 18 canons in 1226 and then increased to 23 by 1242. After a damaging fire in 1270, a rebuilding programme greatly enlarged the building. It was unaffected by the Wars of Scottish Independence but again suffered extensive fire damage in 1390 following an attack by Robert III's brother Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, also known as the Wolf of Badenoch. In 1402 the cathedral precinct again suffered an incendiary attack by the followers of the Lord of the Isles. The number of clerics required to staff the cathedral continued to grow, as did the number of craftsmen needed to maintain the buildings and surroundings.

| Elgin Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Elgin, Moray |

| Country | Scotland |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| History | |

| Authorising papal bull | 10 April 1224 |

| Founded | 1224 (in present position) |

| Founder(s) | Bishop Andreas de Moravia |

| Dedication | The Holy Trinity |

| Dedicated | 19 July 1224 |

| Events | Pre-Reformation

Post-Reformation

|

| Associated people | King Alexander II Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan Alexander Gordon, 1st Earl of Huntly John Shanks |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Ruin |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Style | Gothic |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Moray (est. x1114–1127x1131) |

| Deanery | Elgin Inverness Strathspey Strathbogie |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | (Of significance) Brice de Douglas Andrew de Moravia Alexander Bur Patrick Hepburn |

| Designated | 6 February 1995 |

| Reference no. | SM90142 |

| Category | Ecclesiastical |

The cathedral went through periods of enlargement and renovation following the fires of 1270 and 1390 that included the doubling in length of the choir and the provision of outer aisles to the northern and southern walls of both the nave and choir. Today, these walls are at full height in some places and at foundation level in others yet the overall cruciform shape is still discernible. A mostly intact octagonal chapter house dates from the major enlargement after the fire of 1270. The gable wall above the double door entrance that links the west towers is nearly complete and was rebuilt following the fire of 1390. It accommodates a large window opening that now only contains stub tracery work and fragments of a large rose window. Recessed and chest tombs in both transepts and in the south aisle of the choir contain effigies of bishops and knights, and large flat slabs in the now grass-covered floor of the cathedral mark the positions of early graves. The homes of the dignitaries and canons, or manses, stood in the chanonry and were destroyed by fire on three occasions: in 1270, 1390 and 1402. The two towers of the west front are mostly complete and were part of the first phase of construction. Only the precentor's manse is substantially intact while two others have been incorporated into private buildings. A protective wall of massive proportions surrounded the cathedral precinct, but only a small section has survived. The wall had four access gates, one of which—the Pans Port—still exists.

The number of canons had increased to 25 by the time of the Scottish Reformation in 1560 when the cathedral was abandoned and its services transferred to Elgin's parish church of St Giles. After the removal of the lead waterproofing of the roof in 1567, the cathedral fell steadily into decay. The building was still largely intact in 1615 but in the winter of 1637, a storm brought down the roof covering the eastern limb. In the spring of 1711, the central steeple above the crossing collapsed taking the walls of the nave with it. Ownership was transferred from the Church to the Crown in 1689 but that made no difference to the building's continuing deterioration. Only in the early years of the 19th Century did the Crown begin the conservation process—the stabilisation of the structure proceeded through until the end of the 20th Century with the large-scale improvements to the two western towers.

Early church in Moray

The Diocese of Moray was a regional bishopric unlike the pre-eminent see of the Scottish church, St Andrews, which had evolved from a more ancient monastic Celtic church and administered scattered localities.[2] It is uncertain whether there were bishops of Moray before c. 1120 [3] but the first known prelate—possibly later translated to Dunkeld—was Gregory (or Giric, in Gaelic) and was probably bishop in name only.[4] Gregory was a signatory to the foundation charter of Scone Priory, issued by Alexander I (Alaxandair mac Maíl Choluim) between December 1123 and April 1124,[5] and again in a charter defining the legal rights of the same monastery.[6] He is recorded for the last time when he witnessed a charter granted by David I to Dunfermline Abbey in c. 1128.[7] These actions are all that is known of Gregory with no basis for later assertions that he was a promoted monk in a 'Pictish Church'.[8] After the suppression of Óengus of Moray's rebellion in 1130, King David must have regarded the continued existence of a bishopric in Moray as essential to the stability of the province.[9][10] Yet the next bishop was the absentee titular bishop William (1152–1162), King David's chaplain who had probably been an aide since 1136 and had likely done little to improve the stability of the see by the time he died in 1162.[11] Felix was the next bishop and is thought to have been prelate from 1166 to 1171 although no accurate dates are known—details of his tenure are almost unknown with only one appearance as a witness in a charter of William the Lion at his court held in Elgin.[12] Following Felix's death, Simon de Toeni, King William's kinsman and a former abbot of Coggeshall, in Essex became the next bishop. Bishop Simon was the first of the early bishops to adopt a hands-on attitude towards his diocese and was said to be buried in Birnie Kirk, near Elgin, after his death on 17 September 1184 although this suggestion first appeared in the 18th century.[13] He was followed by Richard of Lincoln, once again a royal clerk, and one who struggled to build up the revenues of the bishopric during and after the insurgence of Domnall mac Uilleim (Donald MacWilliam).[13] Richard is regarded as the first significant resident bishop of the see.[4]

These early bishops had no settled location for their cathedral and sited it successively at the churches of Birnie, Kinneddar and Spynie.[14] Pope Innocent III issued an apostolic bull on 7 April 1206 that allowed bishop Brice de Douglas to fix his cathedral church at Spynie—its inauguration was held between spring 1207 and summer 1208.[15] A chapter of five dignitaries and three ordinary canons was authorised and based its constitution on that of Lincoln Cathedral.[16] Elgin became the lay centre of the province under David I, who probably established the first castle in the town,[10][17] and it may have been this castle, with its promise of better security, that prompted Brice, before July 1216, to petition the Pope to move the seat from Spynie.[18]

Cathedral church at Elgin

Despite Brice's earlier appeal, it was not until Andrew de Moravia's episcopate that Pope Honorius III issued his bull on 10 April 1224 authorising his legates Gilbert de Moravia, Bishop of Caithness, Robert, Abbot of Kinloss and Henry, Dean of Ross to examine the suitability of transferring the cathedra to Elgin.[14][18] The Bishop of Caithness and the Dean of Ross performed the translation ceremony on 19 July 1224.[14] On 5 July, Alexander II (Alaxandair mac Uilliam) had agreed to the transference in an edict that referred to his having given the land previously for this purpose. The land grant predated the Papal mandate and could indicate that work on a new church was already underway before Brice's death but this is thought unlikely and that Bishop Andrew commenced the building works on an unoccupied location.[19][20]

Construction of the cathedral was completed after 1242. Chronicler John of Fordun recorded without explanation that in 1270 the cathedral church and the canons' houses had burned down. The cathedral was rebuilt in a larger and grander style to form the greater part of the structure that is now visible,[21] work that is supposed to have been completed by the outbreak of the Wars of Scottish Independence in 1296. Although Edward I of England took an army to Elgin in 1296 and again in 1303, the cathedral was left unscathed, as it was by his grandson Edward III during his assault on Moray in 1336.[10]

Soon after his election to the see in 1362–63, Bishop Alexander Bur requested funds from Pope Urban V for repairs to the cathedral, citing neglect and hostile attacks.[10] In August 1370 Bur began protection payments to Alexander Stewart, Lord of Badenoch, known as the Wolf of Badenoch, who became Earl of Buchan in 1380, and who was the son of the future King Robert II.[22] Numerous disputes between Bur and Buchan culminated in Buchan's excommunication in February 1390 and the bishop turning to Thomas Dunbar, son of the Earl of Moray, to provide the protection service.[23][24] These acts by the bishop, and any frustration Buchan may have felt about the reappointment of his brother Robert Stewart, Earl of Fife as guardian of Scotland, may have caused him to react defiantly: in May, he descended from his island castle on Lochindorb and burned the town of Forres, followed in June by the burning of Elgin and the cathedral with its manses.[25][26] It is believed that he also burned Pluscarden Priory at this time, which was officially under the Bishop's protection.[27] Bur wrote to Robert III seeking reparation for his brother's actions in a letter stating:[10]

my church was the particular ornament of the fatherland, the glory of the kingdom, the joy of strangers and incoming guests, the object of praise and exaltation in other kingdoms because of its decoration, by which it is believed that God was properly worshipped; not to mention its high bell towers, its venerable furnishings and uncountable jewels.

Robert III granted Bur an annuity of £20 for the period of the bishop's lifetime, and the Pope provided income from the Scottish Church during the following decade.[25] In 1400, Bur wrote to the Abbot of Arbroath complaining that the abbot's prebendary churches in the Moray diocese had not paid their dues towards the cathedral restoration.[28] In the same year Bur wrote to the rector of Aberchirder church, telling him that he now owed three years' arrears of the subsidy that had been imposed on non-prebendary churches in 1397.[29] Again, on 3 July 1402, the burgh and cathedral precinct were attacked, this time by Alexander of Lochaber, brother of Domhnall of Islay, Lord of the Isles; he spared the cathedral but burned the manses. For this act, Lochaber and his captains were excommunicated, prompting Lochaber's return in September to give reparation and gain absolution.[30] In 1408, the money saved during an ecclesiastic vacancy was diverted to the rebuilding process and in 1413 a grant from the customs of Inverness was provided.[31] Increasingly, the appropriation of the parish church revenues led in many cases to churches becoming dilapidated and unable to attract educated priests. By the later Middle Ages, the standard of pastoral care outside the main burghs had significantly declined.[32]

Bishop John Innes (1407–14) contributed greatly to the rebuilding of the cathedral, as evidenced by the inscription on his tomb praising his efforts. When he died, the chapter met secretly—"in quadam camera secreta in campanili ecclesie Moraviensis"—and agreed that should one of their number be elected to the see, the bishop would grant one-third of the income of the bishopric annually until the rebuilding was finished.[33] The major alterations to the west front were completed before 1435 and contain the arms of Bishop Columba de Dunbar (1422–35), and it is presumed that both the north and south aisles of the choir were finished before 1460, as the south aisle contains the tomb of John de Winchester (1435–60).[34] Probably the last important rebuilding feature was the major restructuring of the chapter house between 1482 and 1501, which contains the arms of Bishop Andrew Stewart.[35]

Diocesan organisation

Deaneries of Moray and parishes |

|---|

|

| [36] |

The dignitaries and canons constituted the chapter and had the primary role of aiding the bishop in the governance of the diocese.[37] Often the bishop was the titular head of the chapter only and was excluded from its decision-making processes, the chapter being led by the dean as its superior. As the diocese of Moray based its constitution on that of Lincoln Cathedral, the bishop was allowed to participate within the chapter but only as an ordinary canon.[37][38] Moray was not unique in this: the bishops of Aberdeen, Brechin, Caithness, Orkney and Ross were also canons in their own chapters.[39] Each morning, the canons held a meeting in the chapter house where a chapter from the canonical rulebook of St Benedict was read before the business of the day was discussed.[40] Bishop Brice's chapter of eight clerics consisted of the dean, precentor, treasurer, chancellor, archdeacon and three ordinary canons.[14] His successor, Bishop Andrew de Moravia, greatly expanded the chapter to cater for the much-enlarged establishment by creating two additional hierarchical posts (succentor and subdean) and added 16 more prebendary canons.[41] In total, 23 prebendaries had been created by the time of Andrew's death, and a further two were added just before the Scottish Reformation.[41] Prebendary churches were at the bestowal of the bishop as the churches either were within the diocesan lands or had been granted to the bishop by a landowner as patronage.[42] In the case of Elgin Cathedral, the de Moravia family, of which Bishop Andrew was a member, is noted as having the patronage of many churches given as prebends.[43]

Rural Deans, or deans of Christianity as they were known in the Scottish Church, supervised the priests in the deaneries and implemented the bishop's edicts.[37] There were four deaneries in the Moray diocese—Elgin, Inverness, Strathspey and Strathbogie, and these provided the income not only for the cathedral and chapter but also for other religious houses within and outside the diocese.[41][44] Many churches were allocated to support designated canons, and a small number were held in common. The bishop received mensal and prebendary income in his separate positions as prelate and canon.[45]

The government of the diocese affecting both clergy and laity was vested entirely in the bishop, who appointed officers to the ecclesiastical, criminal and civil courts. The bishop, assisted by his chapter, produced the church laws and regulations for the bishopric and these were enforced at occasional diocesan synods by the bishop or, in his absence, by the dean.[46] Appointed officials adjudicated at consistory courts looking at matters affecting tithes, marriages, divorces, widows, orphans, wills and other related legal matters. In Moray, these courts were held in Elgin and Inverness.[46] By 1452 the Bishop of Moray held all his lands in one regality and had Courts of Regality presided over by Bailiffs and Deputies to ensure the payment of revenues from his estates.[46]

Cathedral offices

Chapter and prebendary churches in 1242 |

|---|

|

| [47] |

Large cathedrals such as Elgin had many chapel altars requiring canons, assisted by a plentiful number of chaplains and vicars, to perform daily services.[14] Bishop Andrew allowed for the canons to be aided by seventeen vicars made up of seven priests, five deacons and five sub-deacons—later the number of vicars was increased to twenty-five.[31] In 1350 the vicars at Elgin could not live on their stipends and Bishop John of Pilmuir provided them with the income from two churches and the patronage of another from Thomas Randolph, second Earl of Moray.[48] By 1489 one vicar had a stipend of 12 marks; six others, 10 marks; one, eight marks; three, seven marks, and six received five marks; each vicar was employed directly by a canon who was required to provide four months' notice in the event of his employment being terminated.[49] The vicars were of two kinds: the vicars-choral who worked chiefly in the choir taking the main services and the chantry chaplains who performed services at the individual foundation altars though there was some overlapping of duties.[50] Although the chapter followed the constitution of Lincoln, the form of divine service copied that of Salisbury Cathedral.[51] It is recorded that Elgin's vicars-choral were subject to disciplinary correction for shortcomings in the performance of the services, resulting in fines. More serious offences could end in corporal punishment, which was administered in the chapter house by the sub-dean and witnessed by the chapter.[52] King Alexander II founded a chaplaincy for the soul of King Duncan I who died in battle with Macbeth near Elgin. The chapel most frequently referenced in records was St Thomas the Martyr, located in the north transept and supported by five chaplains.[53] Other chaplaincies mentioned are those of the Holy Rood, St Catherine, St Duthac, St Lawrence, St Mary Magdalene, St Mary the Virgin and St Michael.[54] By the time of Bishop Bur's episcopate (1362–1397), the cathedral had 15 canons (excluding dignitaries), 22 vicars-choral and about the same number of chaplains.[55]

Despite these numbers, not all the clergy were regularly present at the services in Elgin Cathedral. Absence was an enduring fact of life in all cathedrals in a period when careerist clerics would accept positions in other cathedrals.[31] This is not to say that the time spent away from the chanonry was without permission, as some canons were appointed to be always present while others were allowed to attend on a part-time basis.[56] The dean of Elgin was permanently in attendance; the precentor, chancellor, and treasurer were available for half the year. The non-permanent canons had to attend continuously for three months.[56] The chapter decided in 1240 to penalise persistently absent canons who broke the terms of their attendance by removing one-seventh of their income. In the Diocese of Aberdeen and it is assumed in other bishoprics also, when important decisions of the chapter had to be taken, an absentee canon had to appoint a procurator to act on his behalf—this was usually one of the dignitaries who had a higher likelihood of being present.[57] At Elgin in 1488, many canons were not abiding by the terms of their leave of absence, resulting in each of them receiving a formal warning and a summons; despite this, ten canons refused to attend and had a seventh of their prebendary income deducted.[58] The bulk of the workload fell to the vicars and a smaller number of permanent canons who were responsible for celebrating high mass and for leading and arranging sermons and feast day processions. Seven services were held daily, most of which were solely for the clergy and took place behind the rood screen which separated the high altar and choir from lay worshipers. Only cathedrals, collegiate churches and large burgh churches were resourced to perform the more elaborate services; the services in the parish churches were more basic.[59]

The clergy were augmented by an unknown number of lay lawyers and clerks as well as masons, carpenters, glaziers, plumbers, and gardeners. Master Gregory the mason and Master Richard the glazier are mentioned in the chartulary of the cathedral.[60]

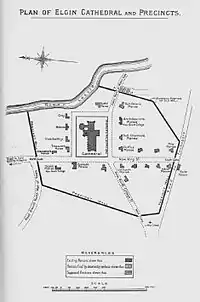

Chanonry and burgh

The chanonry, referred to in the cathedral's chartulary as the college of the chanonry or simply as the college, was the collection of the canons' manses that were grouped around the cathedral.[61] A substantial wall, over 3.5 metres (11 ft) high, 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick and around 820 metres (2,690 ft) in length,[62] enclosed the cathedral and manses and separated the church community from the laity; only the manse of Rhynie lay outside the west wall.[63] The houses of 17 vicars and the many chaplains were also situated outside the west wall.[41] The wall had four gates: the West Port gave access to the burgh, the North Port provided access to the road to the bishop's palace of Spynie, the South Port opened opposite the hospital of Maison Dieu and the surviving East or Panns Port allowed access to the meadowland called Le Pannis. The Panns Port illustrates the portcullis defences of the gate-houses (Fig. 1).[62] Each canon or dignitary was responsible for providing his own manse and was built to reflect his status within the chapter.[61] The castle having become unsuitable, Edward I of England stayed at the manse of Duffus on 10 and 11 September 1303 as did James II in 1455.[64] In 1489, a century after the incendiary attack on the cathedral and precinct in 1390 and 1402, the cathedral records revealed a chanonry still lacking many of its manses. The chapter ordered that 13 canons, including the succentor and the archdeacon, should immediately "erect, construct, build, and duly repair their manses, and the enclosures of their gardens within the college of Moray".[65] The manse of the precentor, erroneously called the Bishop's House,[66] is partially ruined and is dated 1557. (Fig. 2) Vestiges of the Dean's Manse and the Archdeacon's Manse (Fig. 3) are now part of private buildings.[67]

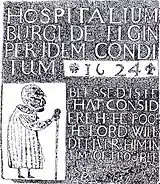

The hospital of Maison Dieu (the Alms House), dedicated to St Mary and situated near the cathedral precinct but outside the chanonry, was established by Bishop Andrew de Moravia before 1237 for the aid of the poor.[68] It suffered fire damage in 1390 and again in 1445. The cathedral clerks received it as a secular benefice but in later years it may, in common with other hospitals, have become dilapidated through a lack of patronage. Bishop James Hepburn granted it to the Blackfriars of Elgin on 17 November 1520, perhaps in an effort to preserve its existence.[69] The property was taken into the ownership of the Crown after the Reformation and in 1595 was granted to the burgh by James VI for educational purposes and for helping the poor.[68] In 1624, an almshouse was constructed to replace the original building, but in 1750 a storm substantially damaged its relatively intact ruins. The remnants of the original building were finally demolished during a 19th-century redevelopment of the area.[70][71]

There were two friaries in the burgh. The Dominican Black Friars friary was founded in the western part of the burgh around 1233. The Franciscan (Friars Minor Conventual) Grey Friars friary was later founded in the eastern part of the burgh sometime before 1281.[72] It is thought that this latter Grey Friars foundation did not long survive, but was followed between 1479 and 1513 by the foundation of a friary near Elgin Cathedral by the Franciscan (Observants) Grey Friars. The building was transferred into the ownership of the burgh around 1559 and later became the Court of Justice in 1563.[73] In 1489, the chapter founded a school that was not purely a song school for the cathedral but was also to be available to provide an education in music and reading for some children of Elgin.[74]

Post–Reformation

In August 1560, parliament assembled in Edinburgh and legislated that the Scottish church would be Protestant, the Pope would have no authority, and that the Catholic mass was illegal.[75] Scottish cathedrals now survived only if they were used as parish churches and as Elgin had been fully served by the Kirk of St Giles, its cathedral was abandoned.[21] An act of parliament passed on 14 February 1567 authorised Regent Lord James Stewart's Privy Council to order the removal of the lead from the roofs of both Elgin and Aberdeen cathedrals, to be sold for the upkeep of his army, but the overladen ship that was intended to take the cargo to Holland capsized and sank in Aberdeen harbour.[76] Regent Moray and Patrick Hepburn, Bishop of Moray ordered repairs to the roof in July 1569, appointing Hew Craigy, Parson of Inverkeithing, as master of the work, to collect contributions from the canons of the diocese.[77]

In 1615, John Taylor, the 'Water Poet', described Elgin Cathedral as "a faire and beautiful church with three steeples, the walls of it and the steeples all yet standing; but the roofes, windowes and many marble monuments and tombes of honourable and worthie personages all broken and defaced".[78]

Decay had set in and the roof of the eastern limb collapsed during a gale on 4 December 1637.[79] In 1640 the General Assembly ordered Gilbert Ross, the minister of St Giles kirk, to remove the rood screen which still partitioned the choir and presbytery from the nave. Ross was assisted in this by the Lairds of Innes and Brodie who chopped it up for firewood.[80][81] It is believed that the destruction of the great west window was caused by Oliver Cromwell's soldiers sometime between 1650 and 1660.[81]

At some point, the cathedral grounds had become the burial ground for Elgin. The town council arranged for the boundary wall to be repaired in 1685 but significantly, the council ordered that the stones from the cathedral should not be used for that purpose.[82] Although the building was becoming increasingly unstable, the chapter house continued to be used for meetings of the Incorporated Trades from 1671 to 1676 and then again from 1701 to around 1731.[83] No attempt was made to stabilise the structure and on Easter Sunday 1711 the central tower gave way, demolishing the nave. Following this collapse, the "quarrying" of the cathedral's stonework for local projects began.[21] Many artists visited Elgin to sketch the ruins, and it is from their work that the slow but continuing ruination can be observed.[84] By the closing years of the 18th century, travellers to Elgin began to visit the ruin, and pamphlets giving the history of the cathedral were prepared for those early tourists. In 1773 Samuel Johnson recorded, "a paper was put into our hands, which deduced from sufficient authorities the history of this venerable ruin."[85]

Since the abolition of bishops within the Scottish Church in 1689, ownership of the abandoned cathedral fell to the crown, but no attempt to halt the decline of the building took place. Acknowledging the necessity to stabilise the structure, the Elgin Town Council initiated the reconstruction of the perimeter wall in 1809 and cleared debris from the surrounding area in about 1815.[86] The Lord Provost of Elgin petitioned the King's Remembrancer for assistance to build a new roof for the chapter house and in 1824, £121 was provided to the architect Robert Reid for its construction. Reid was significant in the development of a conservation policy for historical buildings in Scotland and was to become the first Head of the Scottish Office of Works (SOW) in 1827. It was probably during his tenure at the SOW that the supporting buttresses to the choir and transept walls were built.[84]

In 1824 John Shanks, an Elgin shoemaker and an important figure in the conservation of the cathedral started his work. Sponsored by local gentleman Isaac Forsyth, Shanks cleared the grounds of centuries of rubbish dumping and rubble.[87] Shanks was officially appointed the site's Keeper and Watchman in 1826. Although his work was highly valued at the time and brought the cathedral back into public focus, his unscientific clearance work may have resulted in much valuable evidence of the cathedral's history being lost.[84] He died on 14 April 1841, aged 82. A fortnight later, the Inverness Courier published a commemorative piece on Shanks, calling him the "beadle or cicerone of Elgin Cathedral", and writing:[88]

His unwearied enthusiasm in clearing away the rubbish which encumbered the area of the Cathedral and obscured its architectural beauties, may be gathered from the fact that he removed, with his pick-axe and shovel, 2866 barrowfuls of earth, besides disclosing a flight of steps that led to the grand gateway of the edifice. Tombs and figures, which had long lain hid in obscurity, were unearthed and every monumental fragment of saints and holy men was carefully preserved, and placed in some appropriate situation ... So faithfully did he discharge his duty as keeper of the ruins, that little now remains but to preserve what he accomplished.

Some minor works took place during the remainder of the 19th century and continued into the early 20th century. During the 1930s further maintenance work followed that included a new roof to protect the vaulted ceiling of the south choir aisle. From 1960 onwards the crumbling sandstone blocks were replaced and new windows were fitted in the chapter house, which was re-roofed to preserve its vaulted ceiling. From 1988 to 2000, the two western towers were substantially overhauled with a viewing platform provided at the top of the north tower.

Building phases

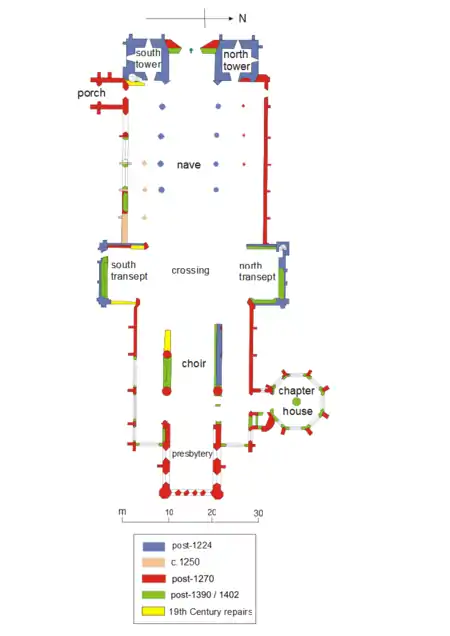

Construction 1224–1270

The first church was markedly cruciform in shape and smaller than the present floor plan. This early structure had a choir without aisles and more truncated, and a nave with only a single aisle on its north and south sides (Fig. 4). The central tower rose above the crossing between the north and south transepts and may have held bells in its upper storey.[89] The north wall of the choir is the earliest extant structure, dating to the years immediately after the church's 1224 foundation; the clerestory windows on top of it are from the later post-1270 reconstruction.[90] This wall has blocked up windows extending to a low level above ground, indicating that it was an external wall and proving that the eastern limb then had no aisle (Fig. 5).[91]

The south transept's southern wall is nearly complete, displaying the fine workmanship of the first phase. It shows the Gothic pointed arch style in the windows that first appeared in France in the mid-12th century and was apparent in England around 1170, but hardly appeared in Scotland until the early 13th century. It also shows the round early Norman window design that continued to be used in Scotland during the entire Gothic period (Fig. 6).[92][93] The windows and the quoins are of finely cut ashlar sandstone.[94] A doorway in the southwest portion of the wall has large mouldings and has a pointed oval window placed above it. Adjacent to the doorway are two lancet-arched windows that are topped at the clerestory level with three round-headed windows.[92] The north transept has much less of its structure preserved, but much of what does remain, taken together with a study by John Slezer in 1693, shows that it was similar to the south transept, except that the north transept had no external door and featured a stone turret containing a staircase.[95]

The west front has two 13th century buttressed towers 27.4 metres (90 ft) high that were originally topped with wooden spires covered in protective lead.[96] Although the difference between the construction of the base course and the transepts suggests that the towers were not part of the initial design, it is likely that the building process was not so far advanced that the masons could fully integrate the nave and towers into each other (Fig. 7).[97]

Enlargement and reconstruction after 1270

After the fire of 1270, a programme of reconstruction was launched, with repairs and a major enlargement. Outer aisles were added to the nave, the eastern wing comprising the choir and presbytery was doubled in length and had aisles provided on its north and south sides, and the octagonal chapter house was built off the new north choir aisle (Figs. 8 & 9).[98] The new northern and southern aisles ran the length of the choir, past the first bay of the presbytery, and contained recessed and chest tombs. The south aisle of the choir contained the tomb of bishop John of Winchester, suggesting a completion date for the reconstructed aisle between 1435 and 1460 (Fig. 10). Chapels were added to the new outer aisles of the nave and were partitioned from each other with wooden screens. The first bay at the west end of each of these aisles and adjacent to the western towers did not contain a chapel but instead had an access door for the laity.[99]

In June 1390, Alexander Stewart, Robert III's brother, burned the cathedral, manses and burgh of Elgin. This fire was very destructive, requiring the central tower to be completely rebuilt along with the principal arcades of the nave. The entire western gable between the towers was reconstructed and the main west doorway and chapter house were refashioned.[100] The internal stonework of the entrance is late 14th or early 15th century and is intricately carved with branches, vines, acorns and oak leaves.[96] A large pointed arch opening in the gable immediately above the main door contained a series of windows, the uppermost of which was a circular or rose window dating from between 1422 and 1435. Just above it can be seen three coats of arms: on the right is that of the bishopric of Moray, in the middle are the Royal Arms of Scotland, and on the left is the armorial shield of Bishop Columba Dunbar (Fig. 11).[96] The walls of the nave are now very low or even at foundation level, except one section in the south wall which is near its original height. This section has windows that appear to have been built in the 15th century to replace the 13th-century openings: they may have been constructed following the 1390 attack (Fig. 12).[101] Nothing of the elevated structure of the nave remains, but its appearance can be deduced from the scarring seen where it attached to the eastern walls of the towers. Nothing of the crossing now remains following the collapse of the central tower in 1711.[99] Elgin Cathedral is unique in Scotland in having an English-style octagonal chapter house and French-influenced double aisles along each side of the nave; in England, only Chichester Cathedral has similar aisles.[102][103] The chapter house, which had been attached to the choir through a short vaulted vestry, required substantial modifications and was now provided with a vaulted roof supported by a single pillar (Figs. 13 & 14). The chapter house measures 10.3 metres (34 ft) high at its apex and 11.3 metres (37 ft) from wall to opposite wall; it was substantially rebuilt by Bishop Andrew Stewart (1482–1501), whose coat of arms is placed on the central pillar.[67] Bishop Andrew was the half-brother of King James II.[104] The delay in the completion of these repairs until this bishop's episcopacy demonstrates the extent of the damage from the 1390 attack.[105]

19th and 20th century stabilisation

In 1847–8 several of the old houses associated with the cathedral on the west side were demolished, and some minor changes were made to the boundary wall. Structural reinforcement of the ruin and some reconstruction work began in the early 20th century, including restoration of the east gable rose window in 1904 and the replacement of the missing form pieces, mullions, and decorative ribs in the window in the north-east wall of the chapter house (Fig. 15).[106] By 1913, repointing the walls and additional waterproofing of the wall tops were completed. In 1924 the ground level was lowered and the 17th-century tomb of the Earl of Huntly was repositioned.[107] Further repairs and restoration ensued during the 1930s, including the partial dismantling of some 19th century buttressing (Fig. 16), the reconstruction of sections of the nave piers using recovered pieces (Fig. 17), and the addition of external roofing to the vault in the south choir in 1939 (Fig. 18).[108] From 1960 to 2000, masons restored the cathedral's crumbling stonework (Fig. 19) and between 1976 and 1988, the window tracery of the chapter house was gradually replaced, and its re-roofing was completed (Fig. 20). Floors, glazing, and a new roof were added to the southwest tower between 1988 and 1998 and comparable restoration work was completed on the northwest tower between 1998 and 2000 (Fig. 21).

Burials

- Andrew de Moravia – buried in the south side of the choir under a large blue marble stone

- David de Moravia – buried in the choir

- William de Spynie – buried in the choir

- Andrew Stewart (d. 1501)

- Alexander Gordon, 1st Earl of Huntly

- Columba de Dunbar (c. 1386 – 1435) was Bishop of Moray from 1422 until his death

- George Gordon, 1st Duke of Gordon and his wife Lady Elizabeth Howard

Referenced figures

| Fig. 1 | Fig. 2 | Fig. 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| The Pans Port | The Precentor's manse | The boundary wall of the Archdeacon's manse with rounded arch gate |

| Fig. 4 | Fig. 5 | Fig. 6 | Fig. 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| The 1224 establishment and then the enlargement after 1270 | North wall of choir showing traces of blocked-in windows | The south wall of the southern transept | Integrated tower and nave construction |

| Fig. 8 | Fig. 9 | Fig. 10 | Fig. 11 | Fig. 12 | Fig. 13 | Fig. 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The octagonal chapter house on the left, and behind it indications of the now missing north choir aisle | The nave in the foreground, the transepts in the middle ground and the choir and choir aisles in the rear ground | Tomb and effigy of Bishop John Winchester (1435–1460) in the south aisle of the choir | West gable apex and arms of Bishopric of Moray (left), Royal arms of Scotland (centre) and Bishop Columba de Dunbar (right) | The 15th century replacement windows in the 13th century openings | Interior of the chapter house showing the central column supporting the vaulted ceiling | The bench reserved for the dean and dignitaries within the chapter house |

| Fig. 15 | Fig. 16 | Fig. 17 | Fig. 18 | Fig. 19 | Fig. 20 | Fig. 21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The replacement of the missing form pieces, mullions, and decorative ribs in the window in the north-east wall of the chapter house | Partial dismantling of some 19th-century buttressing in the 1930s | The rebuilt sections of the nave piers using recovered pieces | External roofing of the vault in the south choir in 1939 | During the last forty years of the 20th century crumbling stonework was restored | Between 1976 and 1988, the chapter house window tracery was gradually replaced and its re-roofing completed | Floors, glazing, and new roofs were added to the west towers between 1988 and 2000 |

References

- Boardman, Early Stewart Kings, pp. 235–6

- Barrow, Kingship and Unity, pp. 67–68

- Cowan, Medieval Religious Houses, p. 206

- Barrow, Kingship and Unity, p. 68

- Watt, Fasti, p. 278

- Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters, pp. 28–30, 44; notes and translation, pp. 279–88; See Kenneth Veitch, Replanting Paradise": Alexander I and the Reform of Religious Life in Scotland in The Innes Review, 52 (Autumn 2001), pp. 140–6, for arguments about the date 1114.

- Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters, p. 63

- Fawcett & Oram, Elgin Cathedral and Diocese, p. 25

- Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500–1286, 2 Vols (Edinburgh, 1922), vol. ii, pp. 173–4, 183; Alan Orr Anderson, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers: AD 500–1286 (London, 1908), republished, Marjorie Anderson (ed.) (Stamford, 1991), pp. 158, 166; for confusion with "Malcom MacHeth", and analysis, see Richard Oram, David: The King Who Made Scotland (Gloucestershire, 2004), pp. 77, 84–7, 90–1, 93, 101, 113–5, 117–8, 189.

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 5

- Fawcett & Oram, Elgin Cathedral and Diocese, pp. 25–6

- Fawcett & Oram, Elgin Cathedral and Diocese, p. 26

- Fawcett & Oram, Elgin Cathedral and Diocese, pp. 26–7

- Cowan & Easson, Medieval Religious Houses, p. 206

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 21

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, pp. 21–2

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 119

- Lost Episcopal Acta

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral p. 23

- Fawcett & Oram, Elgin Cathedral and Diocese, p 30

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 93

- Boardman, Early Stewart Kings, pp. 72–3

- Discussion on the quarrel, see: Grant, Alexander: The Wolf of Badenoch in Moray: Province and People, ed. Seller, W D H, Edinburgh, pp. 143–161; Oram, Richard D: Alexander Bur, Bishop of Moray, 1362–1397 in Barbara Crawford (ed): Church Chronicle and Learning in Medieval and Early Renaissance Scotland, Edinburgh, 1999, pp. 202–204

- Grant, Moray: Province and People, p. 151

- Grant, Moray: Province and People, p. 152

- Boardman, Early Stewart Kings, pp. 175–6

- McCormack, Excavations at Pluscarden Priory, p. 393

- Shaw, History of Moray, p. 388

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 97

- Boardman, Early Stewart Kings, p. 260

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 6

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 83

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, pp. 97–8

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 91

- MacDonald, W. Rae: Notes on the Heraldry of Elgin and its Surrounding District, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1899 Vol. 34 pp. 344–429

- McNeil, MacQueen, Atlas of Scottish History, p. 355

- Fanning, Catholic Encyclopedia, article: Chapter

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 22

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 80

- Historic Scotland, Investigating Elgin Cathedral, p. 10

- Cowan & Easson, Medieval Religious Houses, pp. 206–7

- Cowan, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 20

- Cowan, Medieval Church in Scotland, pp. 20–1

- Watt, Fasti, pp. 316, 317

- Cowan, Parishes, Medieval Scotland, pp. 217–8

- Shaw, History of Moray, pp. 331–2

- Innes, Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis pp. XVII–XXIII

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 73

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland p. 69

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, pp. 30–1

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, pp. 65–6

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 84

- Fawcett,Elgin Cathedral, pp. 6–7

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 7

- Mackintosh, Elgin Past and Present, p. 42

- Dalyell, Records of Bishopric of Moray pp. 13–4

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland p. 83

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland p. 79

- Cowan, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 171

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 31

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 28–9

- Byatt, Elgin: A history, p. 19

- Cant,Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 30

- Taylor, Edward I in North Scotland pp. 213–4

- Dowden, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 94

- The Precentor's manse was granted to Alexander Seton simultaneously with his appointment as lay commendator of Pluscarden Priory. In 1604 he became Chancellor of Scotland and then 1st Earl of Dunfermline in 1606. He renamed the manse to Dunfermline House and became Provost of Elgin (1591–1607) and then Provost of Edinburgh (1598–1608). He died in 1622. See Byatt, Elgin: A History, p. 21

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 92

- Cowan, Medieval Religious Houses, p. 179

- Cowan, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 153

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 95

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 14

- Cowan, Medieval Religious Houses, pp. 118, 127

- Cowan, Medieval Religious Houses, p. 131

- Cowan, Medieval Church in Scotland, p. 181

- Records of the Parliament of Scotland

- Shaw, History of Moray, pp. 284–5

- John Hill Burton, Register of the Privy Council of Scotland: 1545–1569, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1877), p. 677.

- Brown, Early Travellers in Scotland, p. 124

- Shaw, History of Moray p. 285

- Shaw, History of Moray, pp. 290–1

- MacGibbon, Ecclesiastical Architecture, p. 123

- Cramond, Records of Elgin, p. 337

- Mackintosh, Elgin Past and Present, p.68

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 11

- Johnson, Journey to Western Isles p. 19

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, pp. 9, 11

- Shaw, History of Moray, p. 290

- "Inverness Courier Extract". The Northern Highlands in the Nineteenth Century. 28 April 1841. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral Guide, p. 4

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral p. 20

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral pp. 20–21

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 90

- Butler, Scottish Cathedrals and Abbeys, pp. 24–25

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral pp. 21–22

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral p. 26

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p.87

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral p. 15

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, pp. 16–17

- Oram, Moray & Badenoch, p. 89

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 26

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral p. 60

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral p. 18

- Cant, Historic Elgin and its Cathedral, p. 25

- Keith, Historical Catalogue of Scottish Bishops, p. 145

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 62

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 86

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, p. 71

- Fawcett, Elgin Cathedral, pp. 12–13

Sources

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1989). Kingship and Unity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0104-2.

- Bishop, Bruce, B (2001). The Lands and People of Moray: Part 5. Elgin: J & B Bishop. ISBN 978-0-9539369-9-1.

- Boardman, Stephen I. (1996). The Early Stewart Kings: Robert II and Robert III, 1371–1406. John Donald Publishers. ISBN 978-1-904607-68-7.

- Brown, Peter Hume (1970). Early Travellers in Scotland. B. Franklin. ISBN 978-1-84567-744-2.

- Butler, Dugald (2007). Scottish Cathedrals and Abbeys. BiblioLife. ISBN 978-1-110-89589-2.

- Byatt, Mary (2005). Elgin: A History and Celebration of the Town. New York: Ottakers. ISBN 978-0-8337-0384-2.

- Cant, Ronald Gordon. (1974). Historic Elgin and its cathedral. Elgin: Elgin Society. ISBN 978-0-9504028-0-2.

- Cowan, Ian Borthwick; Easson, David Edward (1976). Medieval Religious Houses, Scotland: with an appendix on the houses in the Isle of Man. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-12069-3.

- Cowan, Ian Borthwick; Kirk, James (1995). The Medieval Church in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7073-0732-9.

- Cowan, Ian B. (1967), The Parishes of Medieval Scotland, Scottish Record Society, vol. 93, Edinburgh: Neill & Co. Ltd

- Cramond, William (1908). The Records of Elgin. Aberdeen: New Spalding Club.

- Dalyell, John G. (1826). Records of the Bishopric of Moray. Edinburgh.

- Dowden, John (1910). Medieval Church in Scotland: its Constitution, Organisation and Law. Glasgow: J. MacLehose.

- Fanning, W. (1908). Chapter. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 24 March 2010 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03582b.htm

- Fanning, William (1908). 'Chapter' in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Fawcett, Richard (2001). Elgin Cathedral. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-903570-24-1.

- Fawcett, Richard (1999). Elgin Cathedral: Official Guide. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-900168-65-6.

- Fawcett, Richard; Oram, Richard (2014). Elgin Cathedral and the Diocese of Moray. Historic Scotland. ISBN 978-1-84917-173-1.

- Grant, Alexander (1993). The Wolf of Badenoch [Moray: Province and People]. Edinburgh: Scottish Society for Northern Studies. ISBN 978-0-9505994-7-2.

- "Investigating Elgin Cathedral". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- "John Shanks". Inverness Courier extract. Electric Scotland. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- Johnson, Samuel (1996). A Journey to the Western Isles of Scotland. Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-85715-253-1.

- Innes, Cosmo (1837). Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (1 ed.). Edinburgh: The Ballantyne Club.

- Keith, Robert (1824). An Historical Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops, down to the year 1688. Edinburgh: Bell & Bradfute.

- Lawrie, Archibald C. (1905). Early Scottish Charters Prior to A.D. 1153. Glasgow: J. Mac Lehose and sons.

- "Lost Episcopal Acta" (PDF). Scottish Medieval Charters. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Mackintosh, Herbert B. (1914). Elgin Past and Present. Elgin: J.D. Yeadon.

- McCormack, Finbar (1994). Excavations at Pluscarden Priory, Moray. Vol. 124. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- McNeil, Peter G. B.; MacQueen, Hector L. (1998). An Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (1 ed.). Edinburgh: The Scottish Medievalists. ISBN 978-0950390413.

- Oram, Richard (1996). Moray & Badenoch, A Historical Guide. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-874744-46-7.

- "Records of the Parliament of Scotland to 1707". University of St Andrews. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- Shaw, Lachlan (1882). The History of the Province of Moray 2nd Ed., Vol. III. Glasgow: Hamilton, Adams & Co.

- Taylor, James (1853). Edward I of England in the North of Scotland. Elgin: R. Jeans.

- Watt, D. E. R. (2003). Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae medii aevi ad annum 1638. Edinburgh: Scottish Record Society. ISBN 978-0-902054-19-6.

- Young, Robert (1879). Annals of the Parish and Burgh of Elgin. Elgin.

Further reading

- Clark, W, A series of Views of the Ruins of Elgin Cathedral, Elgin 1826

- Crook, J. Mordant & Port, MH, The History of the King's Works, London, 1973

- Simpson, A T & Stevenson, S, Historic Elgin, the archaeological implications of development, Glasgow: University of Glasgow, Dept. of Archaeology, 1982.

External links

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Elgin Cathedral (SM90142)".

- Photos of Elgin Cathedral

- Firth's Celtic Church

- Latest map of the Chanonry of Elgin

- Engraving of Elgin Cathedral in 1693 by John Slezer at National Library of Scotland