Emperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state.[1][2][3] The image of the emperor or empress was used to signify British authority—his or her profile, for instance, appearing on currency, in government buildings, railway stations, courts, on statues etc. "God Save the King" (or, alternatively, "God Save the Queen") was the national anthem of British India. Oaths of allegiance were made to the emperor or empress and the lawful successors by the governors-general, princes, governors, commissioners in India in events such as imperial durbars.

| Emperor of India | |

|---|---|

| Kaisar-i-Hind | |

Imperial | |

.svg.png.webp) The Star of India and the royal arms | |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Victoria |

| Last monarch | George VI (continued as monarch of India and Pakistan) |

| Formation | 1 May 1876 |

| Abolition | 22 June 1948 |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

The title was abolished on 22 June 1948, with the Indian Independence Act 1947, under which George VI made a royal proclamation that the words "Emperor of India", were to be omitted in styles of address and from customary titles. This was almost a year after he had become king as the titular head of the newly partitioned and independent Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan in 1947. The monarchies were abolished on the establishment of the Republic of India in 1950 and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1956.

Role

Constitutionally speaking, the emperor or empress was the source of all legislative, executive, and judicial authority in the British Indian Empire as the sovereign. However, the emperor or empress took little direct part in the affairs of government. The exercise of sovereign powers was instead delegated from the emperor or empress, either by statute or by convention, to a "viceroy and governor-general", who in turn was appointed by the emperor or empress on the advice of the secretary of state for India, a British minister of the Crown. In addition to serving as the sovereign's representative in India, the viceroy was also ex-officio head of the Imperial Legislative Council and its two houses: a Central Legislative Assembly and a Council of State. Both legislative chambers were composed of delegations from the several provinces and the many princely states. The Imperial Legislative Council's remit was subject to the supremacy of the British Parliament.

Executive power was exercised by the viceroy, as concerned the presidencies and provinces, and by the Indian rulers in relation to the many princely states, on the advice of the Government of India, which operated under the supervision, direction, and control of the India Office in London. The viceroy also had at his disposal the Armed Forces, including the British Indian Army and Royal Indian Navy, together with the Indian Civil Service, other crown servants, and the intelligence services. However, the emperor or empress received certain foreign intelligence reports before the viceroy did.

Judicial power was administered in the sovereign's name by India's various Crown Courts, which by statute had judicial independence from the Government. Other public bodies independent of the Government of India were also legally constituted and empowered from time to time, whether by an Act of Parliament, a statute of the Imperial Legislative Council or by statutory instrument, such as an Order in Council or a royal commission.

History

After the nominal Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar was deposed at the conclusion of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (10 May 1857 – 1 November 1858), the government of the United Kingdom decided to transfer control of British India and its princely states from the mercantile East India Company (EIC) to the Crown, thus marking the beginning of the British Raj. The EIC was officially dissolved on 1 June 1874, and the British prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, decided to offer Queen Victoria the title "empress of India" shortly afterwards. Victoria accepted this style on 1 May 1876. The first Delhi Durbar (which served as an imperial coronation) was held in her honour eight months later on 1 January 1877.[5]

The idea of having Queen Victoria proclaimed empress of India was not particularly new, as Lord Ellenborough had already suggested it in 1843 upon becoming the governor-general of India. By 1874, Major-General Sir Henry Ponsonby, the Queen's private secretary, had ordered English charters to be scrutinised for imperial titles, with Edgar and Stephen mentioned as sound precedents. The Queen, possibly irritated by the sallies of the republicans, the tendency to democracy, and the realisation that her influence was manifestly on the decline, was urging the move.[6] Another factor may have been that the Queen's first child, Victoria, was married to Frederick, the heir apparent to the German Empire. Upon becoming empress, she would outrank her mother.[7] By January 1876, the Queen's insistence was so great that Benjamin Disraeli felt that he could procrastinate no longer.[6] Initially, Victoria had considered the style "Empress of Great Britain, Ireland, and India", but Disraeli had persuaded the Queen to limit the title to India in order to avoid controversy.[8] Hence, the title Kaisar-i-Hind was coined in 1876 by the orientalist G.W. Leitner as the official imperial title for the British monarch in India.[9] The term Kaisar-i-Hind means emperor of India in the vernacular of the Hindi and Urdu languages. The word kaisar, meaning 'emperor', is a derivative of the Roman imperial title caesar (via Persian, Turkish – see Kaiser-i-Rum), and is cognate with the German title Kaiser, which was borrowed from the Latin at an earlier date.[10]

Many in the United Kingdom, however, regarded the assumption of the title as an obvious development from the Government of India Act 1858, which resulted in the founding of British India, ruled directly by the Crown. The public were of the opinion that the title of "queen" was no longer adequate for the ceremonial ruler of what was often referred to informally as the Indian Empire. The new styling underlined the fact that the native states were no longer a mere agglomeration but a collective entity.[11]

When Edward VII ascended to the throne on 22 January 1901, he continued the imperial tradition laid down by his mother, Queen Victoria, by adopting the title Emperor of India. Three subsequent British monarchs followed in his footsteps, and the title continued to be used after India and Pakistan had become independent on 15 August 1947. It was not until 22 June 1948 that the style was officially abolished during the reign of George VI.[2]

The first emperor to visit India was George V. For his imperial coronation ceremony at the Delhi Durbar, the Imperial Crown of India was created. The Crown weighs 920 g (2.03 lb) and is set with 6,170 diamonds, 9 emeralds, 4 rubies, and 4 sapphires. At the front is a very fine emerald weighing 32 carats (6.4 g).[12] The king wrote in his diary that it was heavy and uncomfortable to wear: "Rather tired after wearing my crown for 3+1⁄2 hours; it hurt my head, as it is pretty heavy."[13]

The title "Emperor of India" did not disappear when British India became the Dominion of India (1947–1950) and Dominion of Pakistan (1947–1952) after independence in 1947. George VI retained the title until 22 June 1948, the date of a Royal Proclamation[14] made in accordance with Section 7 (2) of the Indian Independence Act 1947, reading: "The assent of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is hereby given to the omission from the Royal Style and Titles of the words "Indiae Imperator" and the words "Emperor of India" and to the issue by His Majesty for that purpose of His Royal Proclamation under the Great Seal of the Realm."[15] Thereafter, George VI remained monarch of Pakistan until his death in 1952 and of India until it became the Republic of India in 1950.

British coins, as well as those of the Empire and the Commonwealth, had routinely included the abbreviated title Ind. Imp. Coins in India, on the other hand, had the word "empress", and later "king-emperor" in English. The title appeared on coinage in the United Kingdom throughout 1948, with a further Royal Proclamation made on 22 December under the Coinage Act 1870 to omit the abbreviated title.[16]

List of emperors and empresses

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Reign | Death | Consort | Imperial Durbar | Royal House |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Victoria | 24 May 1819 | 1 May 1876 – 22 January 1901 | 22 January 1901 | None[lower-alpha 1] | 1 January 1877 (represented by Lord Lytton) |

Hanover |

.jpg.webp) |

Edward VII | 9 November 1841 | 22 January 1901 – 6 May 1910 | 6 May 1910 |

|

1 January 1903 (represented by Lord Curzon) |

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

.jpg.webp) |

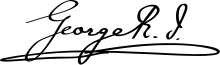

George V | 3 June 1865 | 6 May 1910 – 20 January 1936 | 20 January 1936 |

|

12 December 1911 | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1910–1917) Windsor (1917–1936) |

|

Edward VIII | 23 June 1894 | 20 January 1936 – 11 December 1936 | 28 May 1972 | None | None[lower-alpha 2] | Windsor |

.jpg.webp) |

George VI | 14 December 1895 | 11 December 1936 – 15 August 1947 | 6 February 1952 |

|

None[lower-alpha 3] | Windsor |

See also

- Kaiser-i-Hind Medal

- British India

Notes

- Victoria's husband Prince Albert died on 14 December 1861.

- Edward VIII abdicated after less than one year of reign.

- A durbar was deemed expensive and impractical due to poverty and demands for independence.[17]

References

- "No. 38330". The London Gazette. 22 June 1948. p. 3647. Royal Proclamation of 22 June 1948, made in accordance with the Indian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 GEO. 6. CH. 30.('Section 7: ...(2)The assent of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is hereby given to the omission from the Royal Style and Titles of the words " Indiae Imperator " and the words " Emperor of India " and to the issue by His Majesty for that purpose of His Royal Proclamation under the Great Seal of the Realm.'). According to this Royal Proclamation, the King retained the style and titles 'George VI by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas King, Defender of the Faith'

- Indian Independence Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo. 6. c. 30)

- David Kenneth Fieldhouse (1985). Select Documents on the Constitutional History of the British Empire and Commonwealth: Settler self-government, 1840–1900. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-313-27326-1.

- Harold E. Raugh (2004). The Victorians at War, 1815–1914: An Encyclopedia of British Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 122. ISBN 9781576079256.

- L. A. Knight, "The Royal Titles Act and India", The Historical Journal, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 11, No. 3 (1968), pp. 488–489.

- L. A. Knight, p. 489.

- "Remembering Vicky, the Queen Britain never had". www.newstatesman.com. 10 June 2021.

- L. A. Knight, p. 488.

- B.S. Cohn, "Representing Authority in Victorian India", in E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (eds.), The Invention of Tradition (1983), 165–209, esp. 201-2.

- See Witzel, Michael, "Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts", p. 29, 12.1 PDF Archived 23 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- L. A. Knight, pp. 491, 496

- Edward Francis Twining (1960). A History of the Crown Jewels of Europe. B. T. Batsford. p. 169. ASIN B00283LZA6.

- Brooman, Josh (1989). The World Since 1900 (3rd ed.). Longman. p. 96. ISBN 0-5820-0989-8.

- "No. 38330". The London Gazette. 22 June 1948. p. 3647.

- Indian Independence Act 1947, Section 7 (2)

- "No. 38487". The London Gazette. 24 December 1948. p. 6665.

- Vickers, Hugo (2006), Elizabeth: The Queen Mother, Arrow Books/Random House, p. 175, ISBN 978-0-09-947662-7