Stock

In finance, stock (also capital stock) consists of the shares of which ownership of a corporation or company is divided.[1] (Especially in American English, the word "stocks" is also used to refer to shares.)[1][2] A single share of the stock means fractional ownership of the corporation in proportion to the total number of shares. This typically entitles the shareholder (stockholder) to that fraction of the company's earnings, proceeds from liquidation of assets (after discharge of all senior claims such as secured and unsecured debt),[3] or voting power, often dividing these up in proportion to the amount of money each stockholder has invested. Not all stock is necessarily equal, as certain classes of stock may be issued for example without voting rights, with enhanced voting rights, or with a certain priority to receive profits or liquidation proceeds before or after other classes of shareholders.

| Financial markets |

|---|

|

| Bond market |

|

| Stock market |

|

| Other markets |

|

Derivatives

|

| Over-the-counter (off-exchange) |

|

| Trading |

|

| Related areas |

|

| Securities |

|---|

|

Stock can be bought and sold privately or on stock exchanges, and such transactions are typically heavily regulated by governments to prevent fraud, protect investors, and benefit the larger economy. The stocks are deposited with the depositories in the electronic format also known as Demat account. As new shares are issued by a company, the ownership and rights of existing shareholders are diluted in return for cash to sustain or grow the business. Companies can also buy back stock, which often lets investors recoup the initial investment plus capital gains from subsequent rises in stock price. Stock options issued by many companies as part of employee compensation do not represent ownership, but represent the right to buy ownership at a future time at a specified price. This would represent a windfall to the employees if the option is exercised when the market price is higher than the promised price, since if they immediately sold the stock they would keep the difference (minus taxes).

Shares

A person who owns a percentage of the stock has the ownership of the corporation proportional to their share. The shares form a stock. The stock of a corporation is partitioned into shares, the total of which are stated at the time of business formation. Additional shares may subsequently be authorized by the existing shareholders and issued by the company. In some jurisdictions, each share of stock has a certain declared par value, which is a nominal accounting value used to represent the equity on the balance sheet of the corporation. In other jurisdictions, however, shares of stock may be issued without associated par value.

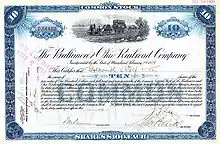

Shares represent a fraction of ownership in a business. A business may declare different types (or classes) of shares, each having distinctive ownership rules, privileges, or share values. Ownership of shares may be documented by issuance of a stock certificate. A stock certificate is a legal document that specifies the number of shares owned by the shareholder, and other specifics of the shares, such as the par value, if any, or the class of the shares.

In the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, South Africa, and Australia, stock can also refer, less commonly, to all kinds of marketable securities.[4]

Types

Stock typically takes the form of shares of either common stock or preferred stock. As a unit of ownership, common stock typically carries voting rights that can be exercised in corporate decisions. Preferred stock differs from common stock in that it typically does not carry voting rights but is legally entitled to receive a certain level of dividend payments before any dividends can be issued to other shareholders.[5][6] Convertible preferred stock is preferred stock that includes an option for the holder to convert the preferred shares into a fixed number of common shares, usually any time after a predetermined date. Shares of such stock are called "convertible preferred shares" (or "convertible preference shares" in the UK).

New equity issue may have specific legal clauses attached that differentiate them from previous issues of the issuer. Some shares of common stock may be issued without the typical voting rights, for instance, or some shares may have special rights unique to them and issued only to certain parties. Often, new issues that have not been registered with a securities governing body may be restricted from resale for certain periods of time.

Preferred stock may be hybrid by having the qualities of bonds of fixed returns and common stock voting rights. They also have preference in the payment of dividends over common stock and also have been given preference at the time of liquidation over common stock. They have other features of accumulation in dividend. In addition, preferred stock usually comes with a letter designation at the end of the security; for example, Berkshire-Hathaway Class "B" shares sell under stock ticker BRK.B, whereas Class "A" shares of ORION DHC, Inc will sell under ticker OODHA until the company drops the "A" creating ticker OODH for its "Common" shares only designation. This extra letter does not mean that any exclusive rights exist for the shareholders but it does let investors know that the shares are considered for such, however, these rights or privileges may change based on the decisions made by the underlying company.

Rule 144 stock

"Rule 144 Stock" is an American term given to shares of stock subject to SEC Rule 144: Selling Restricted and Control Securities.[7] Under Rule 144, restricted and controlled securities are acquired in unregistered form. Investors either purchase or take ownership of these securities through private sales (or other means such as via ESOPs or in exchange for seed money) from the issuing company (as in the case with Restricted Securities) or from an affiliate of the issuer (as in the case with Control Securities). Investors wishing to sell these securities are subject to different rules than those selling traditional common or preferred stock. These individuals will only be allowed to liquidate their securities after meeting the specific conditions set forth by SEC Rule 144. Rule 144 allows public re-sale of restricted securities if a number of different conditions are met.

Stock derivatives

A stock derivative is any financial instrument for which the underlying asset is the price of an equity. Futures and options are the main types of derivatives on stocks. The underlying security may be a stock index or an individual firm's stock, e.g. single-stock futures.

Stock futures are contracts where the buyer is long, i.e., takes on the obligation to buy on the contract maturity date, and the seller is short, i.e., takes on the obligation to sell. Stock index futures are generally delivered by cash settlement.

A stock option is a class of option. Specifically, a call option is the right (not obligation) to buy stock in the future at a fixed price and a put option is the right (not obligation) to sell stock in the future at a fixed price. Thus, the value of a stock option changes in reaction to the underlying stock of which it is a derivative. The most popular method of valuing stock options is the Black–Scholes model.[8] Apart from call options granted to employees, most stock options are transferable.

History

During the Roman Republic, the state contracted (leased) out many of its services to private companies. These government contractors were called publicani, or societas publicanorum as individual companies.[9] These companies were similar to modern corporations, or joint-stock companies more specifically, in a couple of aspects. They issued shares called partes (for large cooperatives) and particulae which were small shares that acted like today's over-the-counter shares.[10] Polybius mentions that "almost every citizen" participated in the government leases.[11] There is also evidence that the price of stocks fluctuated. The Roman orator Cicero speaks of partes illo tempore carissimae, which means "shares that had a very high price at that time".[12] This implies a fluctuation of price and stock market behavior in Rome.

Around 1250 in France at Toulouse, 100 shares of the Société des Moulins du Bazacle, or Bazacle Milling Company were traded at a value that depended on the profitability of the mills the society owned.[13] As early as 1288, the Swedish mining and forestry products company Stora has documented a stock transfer, in which the Bishop of Västerås acquired a 12.5% interest in the mine (or more specifically, the mountain in which the copper resource was available, the Great Copper Mountain) in exchange for an estate.

The earliest recognized joint-stock company in modern times was the English (later British) East India Company, one of the most notorious joint-stock companies. It was granted an English Royal Charter by Elizabeth I on 31 December 1600, with the intention of favouring trade privileges in India. The Royal Charter effectively gave the newly created Honourable East India Company (HEIC) a 15-year monopoly on all trade in the East Indies.[14] The company transformed from a commercial trading venture to one that virtually ruled India as it acquired auxiliary governmental and military functions, until its dissolution.

Soon afterwards, in 1602,[15] the Dutch East India Company issued the first shares that were made tradeable on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, an invention that enhanced the ability of joint-stock companies to attract capital from investors as they now easily could dispose of their shares.[16] The Dutch East India Company became the first multinational corporation and the first megacorporation. Between 1602 and 1796 it traded 2.5 million tons of cargo with Asia on 4,785 ships and sent a million Europeans to work in Asia, surpassing all other rivals.

The innovation of joint ownership made a great deal of Europe's economic growth possible following the Middle Ages. The technique of pooling capital to finance the building of ships, for example, made the Netherlands a maritime superpower. Before the adoption of the joint-stock corporation, an expensive venture such as the building of a merchant ship could be undertaken only by governments or by very wealthy individuals or families.

The Dutch stock market of the 17th century included the use of stock futures, stock options, short selling, the use of credit to purchase shares, a speculative bubble that crashed in 1695, and a change in fashion (namely, in headdresses) that unfolded and reverted in time with the market. Edward Stringham also noted that the uses of practices such as short selling continued to occur during this time despite the government passing laws against it. This is unusual because it shows individual parties fulfilling contracts that were not legally enforceable and where the parties involved could incur a loss. Stringham argues that this shows that contracts can be created and enforced without state sanction or, in this case, in spite of laws to the contrary.[17][18]

Shareholder

A shareholder (or stockholder) is an individual or company (including a corporation) that legally owns one or more shares of stock in a joint stock company. Both private and public traded companies have shareholders.

Shareholders are granted special privileges depending on the class of stock, including the right to vote on matters such as elections to the board of directors, the right to share in distributions of the company's income, the right to purchase new shares issued by the company, and the right to a company's assets during a liquidation of the company. However, shareholder's rights to a company's assets are subordinate to the rights of the company's creditors.

Shareholders are one type of stakeholders, who may include anyone who has a direct or indirect equity interest in the business entity or someone with a non-equity interest in a non-profit organization. Thus it might be common to call volunteer contributors to an association stakeholders, even though they are not shareholders.

Although directors and officers of a company are bound by fiduciary duties to act in the best interest of the shareholders, the shareholders themselves normally do not have such duties towards each other.

However, in a few unusual cases, some courts have been willing to imply such a duty between shareholders. For example, in California, USA, majority shareholders of closely held corporations have a duty not to destroy the value of the shares held by minority shareholders.[19][20]

The largest shareholders (in terms of percentages of companies owned) are often mutual funds, and, especially, passively managed exchange-traded funds.

Application

The owners of a private company may want additional capital to invest in new projects within the company. They may also simply wish to reduce their holding, freeing up capital for their own private use. They can achieve these goals by selling shares in the company to the general public, through a sale on a stock exchange. This process is called an initial public offering, or IPO.

By selling shares they can sell part or all of the company to many part-owners. The purchase of one share entitles the owner of that share to literally share in the ownership of the company, a fraction of the decision-making power, and potentially a fraction of the profits, which the company may issue as dividends. The owner may also inherit debt and even litigation.

In the common case of a publicly traded corporation, where there may be thousands of shareholders, it is impractical to have all of them making the daily decisions required to run a company. Thus, the shareholders will use their shares as votes in the election of members of the board of directors of the company.

In a typical case, each share constitutes one vote. Corporations may, however, issue different classes of shares, which may have different voting rights. Owning the majority of the shares allows other shareholders to be out-voted – effective control rests with the majority shareholder (or shareholders acting in concert). In this way the original owners of the company often still have control of the company.

Shareholder rights

Although ownership of 50% of shares does result in 50% ownership of a company, it does not give the shareholder the right to use a company's building, equipment, materials, or other property. This is because the company is considered a legal person, thus it owns all its assets itself. This is important in areas such as insurance, which must be in the name of the company and not the main shareholder.

In most countries, boards of directors and company managers have a fiduciary responsibility to run the company in the interests of its stockholders. Nonetheless, as Martin Whitman writes:

- ...it can safely be stated that there does not exist any publicly traded company where management works exclusively in the best interests of OPMI [Outside Passive Minority Investor] stockholders. Instead, there are both "communities of interest" and "conflicts of interest" between stockholders (principal) and management (agent). This conflict is referred to as the principal–agent problem. It would be naive to think that any management would forego management compensation, and management entrenchment, just because some of these management privileges might be perceived as giving rise to a conflict of interest with OPMIs.[21]

Even though the board of directors runs the company, the shareholder has some impact on the company's policy, as the shareholders elect the board of directors. Each shareholder typically has a percentage of votes equal to the percentage of shares he or she owns. So as long as the shareholders agree that the management (agent) are performing poorly they can select a new board of directors which can then hire a new management team. In practice, however, genuinely contested board elections are rare. Board candidates are usually nominated by insiders or by the board of the directors themselves, and a considerable amount of stock is held or voted by insiders.

Owning shares does not mean responsibility for liabilities. If a company goes broke and has to default on loans, the shareholders are not liable in any way. However, all money obtained by converting assets into cash will be used to repay loans and other debts first, so that shareholders cannot receive any money unless and until creditors have been paid (often the shareholders end up with nothing).[22]

Means of financing

Financing a company through the sale of stock in a company is known as equity financing. Alternatively, debt financing (for example issuing bonds) can be done to avoid giving up shares of ownership of the company. Unofficial financing known as trade financing usually provides the major part of a company's working capital (day-to-day operational needs).

Trading

In general, the shares of a company may be transferred from shareholders to other parties by sale or other mechanisms, unless prohibited. Most jurisdictions have established laws and regulations governing such transfers, particularly if the issuer is a publicly traded entity.

The desire of stockholders to trade their shares has led to the establishment of stock exchanges, organizations which provide marketplaces for trading shares and other derivatives and financial products. Today, stock traders are usually represented by a stockbroker who buys and sells shares of a wide range of companies on such exchanges. A company may list its shares on an exchange by meeting and maintaining the listing requirements of a particular stock exchange.

Many large non-U.S companies choose to list on a U.S. exchange as well as an exchange in their home country in order to broaden their investor base. These companies must maintain a block of shares at a bank in the US, typically a certain percentage of their capital. On this basis, the holding bank establishes American depositary shares and issues an American depositary receipt (ADR) for each share a trader acquires. Likewise, many large U.S. companies list their shares at foreign exchanges to raise capital abroad.

Small companies that do not qualify and cannot meet the listing requirements of the major exchanges may be traded over-the-counter (OTC) by an off-exchange mechanism in which trading occurs directly between parties. The major OTC markets in the United States are the electronic quotation systems OTC Bulletin Board (OTCBB) and OTC Markets Group (formerly known as Pink OTC Markets Inc.)[23] where individual retail investors are also represented by a brokerage firm and the quotation service's requirements for a company to be listed are minimal. Shares of companies in bankruptcy proceedings are usually listed by these quotation services after the stock is delisted from an exchange.

Buying

There are various methods of buying and financing stocks, the most common being through a stockbroker. Brokerage firms, whether they are a full-service or discount broker, arrange the transfer of stock from a seller to a buyer. Most trades are actually done through brokers listed with a stock exchange.

There are many different brokerage firms from which to choose, such as full service brokers or discount brokers. The full service brokers usually charge more per trade, but give investment advice or more personal service; the discount brokers offer little or no investment advice but charge less for trades. Another type of broker would be a bank or credit union that may have a deal set up with either a full-service or discount broker.

There are other ways of buying stock besides through a broker. One way is directly from the company itself. If at least one share is owned, most companies will allow the purchase of shares directly from the company through their investor relations departments. However, the initial share of stock in the company will have to be obtained through a regular stock broker. Another way to buy stock in companies is through Direct Public Offerings which are usually sold by the company itself. A direct public offering is an initial public offering in which the stock is purchased directly from the company, usually without the aid of brokers.

When it comes to financing a purchase of stocks there are two ways: purchasing stock with money that is currently in the buyer's ownership, or by buying stock on margin. Buying stock on margin means buying stock with money borrowed against the value of stocks in the same account. These stocks, or collateral, guarantee that the buyer can repay the loan; otherwise, the stockbroker has the right to sell the stock (collateral) to repay the borrowed money. He can sell if the share price drops below the margin requirement, at least 50% of the value of the stocks in the account. Buying on margin works the same way as borrowing money to buy a car or a house, using a car or house as collateral. Moreover, borrowing is not free; the broker usually charges 8–10% interest.

Selling

Selling stock is procedurally similar to buying stock. Generally, the investor wants to buy low and sell high, if not in that order (short selling); although a number of reasons may induce an investor to sell at a loss, e.g., to avoid further loss.

As with buying a stock, there is a transaction fee for the broker's efforts in arranging the transfer of stock from a seller to a buyer. This fee can be high or low depending on which type of brokerage, full service or discount, handles the transaction.

After the transaction has been made, the seller is then entitled to all of the money. An important part of selling is keeping track of the earnings. Importantly, on selling the stock, in jurisdictions that have them, capital gains taxes will have to be paid on the additional proceeds, if any, that are in excess of the cost basis.

Short selling

Short selling consists of an investor immediately selling borrowed shares and then buying them back when their price has gone down (called "covering").[24] Essentially, such an investor bets[24] that the price of the shares will drop so that they can be bought back at the lower price and thus returned to the lender at a profit.

Risks of short selling

The risks of short selling stock are usually higher than those of buying stock. This is because the loss can theoretically be unlimited since the stock's value can theoretically go up indefinitely.[24]

Stock price fluctuations

The price of a stock fluctuates fundamentally due to the theory of supply and demand. Like all commodities in the market, the price of a stock is sensitive to demand. However, there are many factors that influence the demand for a particular stock. The fields of fundamental analysis and technical analysis attempt to understand market conditions that lead to price changes, or even predict future price levels. A recent study shows that customer satisfaction, as measured by the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI), is significantly correlated to the market value of a stock.[25] Stock price may be influenced by analysts' business forecast for the company and outlooks for the company's general market segment. Stocks can also fluctuate greatly due to pump and dump scams. Also see List of S&P 600 companies.

Share price determination

At any given moment, an equity's price is strictly a result of supply and demand. The supply, commonly referred to as the float, is the number of shares offered for sale at any one moment. The demand is the number of shares investors wish to buy at exactly that same time. The price of the stock moves in order to achieve and maintain equilibrium. The product of this instantaneous price and the float at any one time is the market capitalization of the entity offering the equity at that point in time.

When prospective buyers outnumber sellers, the price rises. Eventually, sellers attracted to the high selling price enter the market and/or buyers leave, achieving equilibrium between buyers and sellers. When sellers outnumber buyers, the price falls. Eventually buyers enter and/or sellers leave, again achieving equilibrium.

Thus, the value of a share of a company at any given moment is determined by all investors voting with their money. If more investors want a stock and are willing to pay more, the price will go up. If more investors are selling a stock and there aren't enough buyers, the price will go down.

- Note: "For Nasdaq-listed stocks, the price quote includes information on the bid and ask prices for the stock."[26]

That does not explain how people decide the maximum price at which they are willing to buy or the minimum at which they are willing to sell. In professional investment circles the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) continues to be popular, although this theory is widely discredited in academic and professional circles. Briefly, EMH says that investing is overall (weighted by the standard deviation) rational; that the price of a stock at any given moment represents a rational evaluation of the known information that might bear on the future value of the company; and that share prices of equities are priced efficiently, which is to say that they represent accurately the expected value of the stock, as best it can be known at a given moment. In other words, prices are the result of discounting expected future cash flows.

The EMH model, if true, has at least two interesting consequences. First, because financial risk is presumed to require at least a small premium on expected value, the return on equity can be expected to be slightly greater than that available from non-equity investments: if not, the same rational calculations would lead equity investors to shift to these safer non-equity investments that could be expected to give the same or better return at lower risk. Second, because the price of a share at every given moment is an "efficient" reflection of expected value, then—relative to the curve of expected return—prices will tend to follow a random walk, determined by the emergence of information (randomly) over time. Professional equity investors therefore immerse themselves in the flow of fundamental information, seeking to gain an advantage over their competitors (mainly other professional investors) by more intelligently interpreting the emerging flow of information (news).

The EMH model does not seem to give a complete description of the process of equity price determination. For example, stock markets are more volatile than EMH would imply. In recent years it has come to be accepted that the share markets are not perfectly efficient, perhaps especially in emerging markets or other markets that are not dominated by well-informed professional investors.

Another theory of share price determination comes from the field of Behavioral Finance. According to Behavioral Finance, humans often make irrational decisions—particularly, related to the buying and selling of securities—based upon fears and misperceptions of outcomes. The irrational trading of securities can often create securities prices which vary from rational, fundamental price valuations. For instance, during the technology bubble of the late 1990s (which was followed by the dot-com bust of 2000–2002), technology companies were often bid beyond any rational fundamental value because of what is commonly known as the "greater fool theory". The "greater fool theory" holds that, because the predominant method of realizing returns in equity is from the sale to another investor, one should select securities that they believe that someone else will value at a higher level at some point in the future, without regard to the basis for that other party's willingness to pay a higher price.Thus, even a rational investor may bank on others' irrationality.

Arbitrage trading

When companies raise capital by offering stock on more than one exchange, the potential exists for discrepancies in the valuation of shares on different exchanges. A keen investor with access to information about such discrepancies may invest in expectation of their eventual convergence, known as arbitrage trading. Electronic trading has resulted in extensive price transparency (efficient-market hypothesis) and these discrepancies, if they exist, are short-lived and quickly equilibrated.

See also

- Arrangements between railroads

- Boiler room

- Bucket shop

- Buying in (securities)

- Concentrated stock

- Employee stock ownership

- Equity investment

- GICS

- Golden share

- House stock

- Insider trading

- Money managers

- Naked short selling

- Penny stock

- Scripophily

- Social ownership

- Stock and flow

- Stock dilution

- Stock valuation

- Stock token

- Stub (stock)

- Tracking stock

- Treasury stock

- Traditional and alternative investments

- Voting interest

References

- Longman Business English Dictionary:

"stock - especially AmE one of the shares into which ownership of a company is divided, or these shares considered together"

"When a company issues shares or stocks especially AmE, it makes them available for people to buy for the first time." - stock in Collins English Dictionary: "A stock is one of the parts or shares that the value of a company is divided into, that people can buy."

- "stock Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- "Common Stock vs. Preferred Stock, and Stock Classes". InvestorGuide.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- Zvi Bodie, Alex Kane, Alan J. Marcus, Investments, 9th Ed., ISBN 978-0078034695.

- "Rule 144: Selling Restricted and Control Securities". US Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "Black Scholes Calculator". Tradingtoday.com. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita

- (Cic. pro Rabir. Post. 2; Val. Max. VI.9 §7)

- (Polybius, 6, 17, 3)

- (Cicero, P. VAT. 12, 29.)

- "Paris: It Started with the Lyons Bourse | NYSE Euronext". Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- Irwin, Douglas A. (December 1991). "Mercantilism as Strategic Trade Policy: The Anglo-Dutch Rivalry for the East India Trade" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. The University of Chicago Press. 99 (6): 1296–1314. doi:10.1086/261801. JSTOR 2937731. S2CID 17937216. at 1299.

- Stringham, Edward (2003). "The Extralegal Development of Securities Trading in Seventeenth Century Amsterdam". The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. SSRN 1676251.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - The oldest share in the world, issued by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC), 1606.

- Stringham, Edward (2002). "The Origin of the London Stock Exchange as a Self Policing Club". Journal of Private Enterprise. 17 (2): 1–19. SSRN 1676253.

- "Devil the Hindmost" by Edward Chancellor.

- Jones v. H. F. Ahmanson & Co., 1 Cal. 3d)

- "Jones v. H.F. Ahmanson & Co. (1969) 1 C3d 93". Online.ceb.com. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Whitman, 2004, 5

- Jackson, Thomas (2001). The Logic and Limits of Bankruptcy Law. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-58798-114-9.

- "Stock Trading". US Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- How an Investor Makes Money Short Selling Stocks, Investopedia.com

- Mithas, Sunil (January 2006). "Increased Customer Satisfaction Increases Stock Price". Research@Smith. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Understanding Stock Prices: Bid, Ask, Spread". Youngmoney.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

Further reading

- Graham, Benjamin; Jason Zweig (8 July 2003) [1949]. The Intelligent Investor. Warren E. Buffett (collaborator) (2003 ed.). HarperCollins. front cover. ISBN 0-06-055566-1.

- Graham, B. and Dodd, D. and Dodd, D.L.F. (1934). Security Analysis: The Classic 1934 Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-070-24496-2. LCCN 34023635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the Rich Teach Their Kids About Money That the Poor and Middle Class Do Not!, by Robert Kiyosaki and Sharon Lechter. Warner Business Books, 2000. ISBN 0-446-67745-0

- Clason, George (2015). The Richest Man in Babylon: Original 1926 Edition. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-508-52435-9.

- Bogle, John Bogle (2007). The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 216. ISBN 9780470102107.

- Buffett, W. and Cunningham, L.A. (2009). The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Investors and Managers. John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte Limited. ISBN 978-0-470-82441-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Stanley, Thomas J. and Danko, W.D. (1998). The Millionaire Next Door. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-0-671-01520-6. LCCN 98046515.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Soros, George (1988). The Alchemy of Finance: Reading the Mind of the Market. A Touchstone book. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-66238-7. LCCN 87004745.

- Fisher, Philip Arthur (1996). Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings. Wiley Investment Classics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-11927-2. LCCN 95051449.