European Capital of Culture

A European Capital of Culture is a city designated by the European Union (EU) for a period of one calendar year during which it organises a series of cultural events with a strong pan-European dimension. Being a European Capital of Culture can be an opportunity for a city to generate considerable cultural, social and economic benefits and it can help foster urban regeneration, change the city's image and raise its visibility and profile on an international scale. Multiple cities can be a European Capital of Culture simultaneously.

In 1985, Melina Mercouri, Greece’s Minister of Culture, and her French counterpart Jack Lang came up with the idea of designating an annual City of Culture to bring Europeans closer together by highlighting the richness and diversity of European cultures and raising awareness of their common history and values. It is strongly believed that the ECoC significantly maximises social and economic benefits, especially when the events are embedded as a part of a long–term culture-based development strategy of the city and the surrounding region.[1]

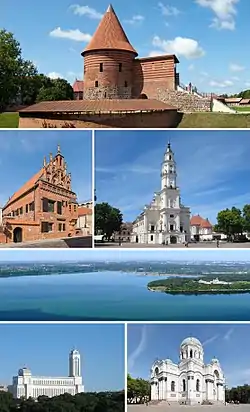

The Commission of the European Union manages the title and each year the Council of Ministers of the European Union formally designates European Capitals of Culture: more than 40 cities have been designated so far. The current European Capitals of Culture for 2022 are Esch-sur-Alzette in Luxembourg, Kaunas in Lithuania and Novi Sad in Serbia.

Selection process

.jpg.webp)

An international panel of cultural experts is in charge of assessing the proposals of cities for the title according to criteria specified by the European Union.

For two of the capitals each year, eligibility is open to cities in EU member states only. From 2021 and every three years thereafter, a third capital will be chosen from cities in countries that are candidates or potential candidates for membership, or in countries that are part of the European Economic Area (EEA)[2][3]– an example of the latter being Stavanger, Norway, which was a European Capital of Culture in 2008.

A 2004 study conducted for the Commission, known as the "Palmer report", demonstrated that the choice of European Capital of Culture served as a catalyst for cultural development and the transformation of the city.[4] Consequently, the beneficial socio-economic development and impact for the chosen city are now also considered in determining the chosen cities.

Bids from five United Kingdom cities to be the 2023 Capital of Culture were disqualified in November 2017, because the UK was planning to leave the EU before 2023.[5]

History

The European Capital of Culture programme was initially called the European City of Culture and was conceived in 1983, by Melina Mercouri, then serving as minister of culture in Greece. Mercouri believed that at the time, culture was not given the same attention as politics and economics and a project for promoting European cultures within the member states should be pursued. The European City of Culture programme was launched in the summer of 1985 with Athens being the first title-holder.[6] In 1999, the European City of Culture program was renamed to European Capital of Culture.[7]

List of European Capitals of Culture

1 The European Capital of Culture was due to be in the UK in 2023. However, due to its decision to leave the European Union, UK cities would no longer be eligible to hold the title after 2019. The European Commission's Scotland office confirmed that this would be the case on 23 November 2017, only one week before the UK was due to announce which city would be put forward.[21] The candidate cities were Dundee,[22] Leeds, Milton Keynes,[23] Nottingham and a joint bid from Northern Irish cities Belfast, Derry and Strabane.[24] This caused anger amongst the UK candidate cities' bidding teams due to the short notice of the decision, and because of the amount of money they had already spent preparing their bids.

2 A new framework makes it possible for cities in candidate countries (Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey), potential candidates for EU membership (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo) or EFTA member states (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland) to hold the title every third year as of 2021. This will be selected through an open competition, meaning that cities from various countries may compete with each other.[25]

See also

- American Capital of Culture – In the Americas, title awarded annually by American Capital of Culture Organization, an NGO

- Arab Capital of Culture – Arab League effort to promote and celebrate Arab culture

- European Green Capital Award – Award for a European city based on its environmental record

- European Youth Capital – One year city award

- European Region of Gastronomy – Regional title

- University Network of the European Capitals of Culture – International non-profit association

References

- Burkšienė, V., Dvorak, J., Burbulytė-Tsiskarishvili, G. (2018). Sustainability and Sustainability Marketing in Competing for the Title of European Capital of Culture. Organizacija, Vol. 51 (1), p. 66-78 Archived 17 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "Decision No 445/2014/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014". 3 May 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "European Capitals of Culture 2020 to 2033 — A guide for cities preparing to bid" (PDF). European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Palmer, Robert (2004) "European Cities and Capitals of Culture" Part I. Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Part II. Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Study prepared for the European Commission

- "Brexit blow to UK 2023 culture crown bids". BBC News. 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Kiran Klaus Patel, ed., The Cultural Politics of Europe: European Capitals of Culture and European Union since the 1980s (London: Routledge, 2013)

- "History – UNeECC". Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Association of European Cities of Culture of the Year 2000 - KRAKOW THE OPEN CITY". www.krakow.pl. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Trenčín to be the European Capital of Culture 2026 in Slovakia". europa.eu. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- "4 cities short-listed for European capitals of culture 2027 in Portugal". European Union. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Designated European Capitals of Culture". European Union. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- "RUM". Rum.pt. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- "Call for applications for 2028 European Capital of Culture for cities in EFTA/EEA-, candidate-, and in potential candidates for EU membership countries". European Commission. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- {{Cite web |title=Soutěž Evropské hlavní město kultury 2028 zná své finalisty |url=https://www.mkcr.cz/novinky-a-media/soutez-evropske-hlavni-mesto-kultury-2028-zna-sve-finalisty-4-cs4988.html%7Cpublisher=Ministry of Culture Czech Republic |date=14 October 2022 |access-date=22 October 2022 |language=Czech}

- {{Cite web |title=APPEL à CANDIDATURE – Capitale européenne de la Culture 2028 |url=https://www.mkcr.cz/evropske-hlavni-mesto-kultury-54.html |work=Ministerstvo Kultury |access-date=4 October 2022 |language=Czech}

- "Capitale européenne de la Culture 2028". Ministère de la Culture (in French). Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "Ecoc 2028, Here are the first candidate cities". Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "Leuven stelt zich kandidaat als Europese Culturele Hoofdstad 2030". demorgen.be. 15 December 2017. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Vild plan: Vil gøre Næstved til europæisk kulturhovedstad". 11 January 2022. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Torino Capitale europea della Cultura nel 2033? Il Consiglio comunale dice "sì" alla candidatura". Torino Oggi. 19 April 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- Brady, Jon (23 November 2017). "Brexit destroys Dundee's hopes of being European Capital of Culture in 2023". Evening Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Lorimer, Scott. "The latest news and sport from Dundee, Tayside and Fife". Evening Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- "European Capital of Culture". www.milton-keynes.gov.uk. Milton Keynes Council. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Meredith, Robbie (5 July 2017). "NI councils make bid for European Capital of Culture title". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "European Capitals of Culture". European Union. 6 February 2021. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

External links

- European Capitals of Culture

- Decision No 1622/2006/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 2006 establishing a Community action for the European Capital of Culture event for the years 2007 to 2019

- Decision No 445/2014/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 establishing a Union action for the European Capitals of Culture for the years 2020 to 2033 and repealing Decision No 1622/2006/EC