Family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a woman wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which she wishes to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marital situation, career or work considerations, financial situations. If sexually active, family planning may involve the use of contraception and other techniques to control the timing of reproduction.

.jpg.webp)

Family planning has been of practice since the 16th century by the people of Djenné in West Africa, when physicians advised women to space their births at three-year intervals.[1] Others aspects of family planning aside from contraception include sex education,[2][3] prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections,[2] pre-conception counseling[2] and management, and infertility management.[4] Family planning, as defined by the United Nations and the World Health Organization, encompasses services leading up to conception. Abortion is not typically recommended as a primary method of family planning,[5] and access to contraception reduces the need for abortion.[6]

Family planning is sometimes used as a synonym or euphemism for access to and the use of contraception. However, it often involves methods and practices in addition to contraception. Additionally, many might wish to use contraception but are not necessarily planning a family (e.g., unmarried adolescents, young married couples delaying childbearing while building a career). Family planning has become a catch-all phrase for much of the work undertaken in this realm. However, contemporary notions of family planning tend to place a woman and her childbearing decisions at the center of the discussion, as notions of women's empowerment and reproductive autonomy have gained traction in many parts of the world. It is usually applied to a female-male couple who wish to limit the number of children they have or control pregnancy timing (also known as spacing children).

Family planning has been shown to reduce teenage birth rates and birth rates for unmarried women.[7][8][9]

Purposes

In 2006, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued a recommendation, encouraging men and women to formulate a reproductive life plan, to help them in avoiding unintended pregnancies and to improve the health of women and reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes.[10]

There are multiple benefits to family planning including spacing births for healthier pregnancies, thus decreasing risks of maternal morbidity, fetal prematurity and low birth. There is also a potential positive impact on the individual's social and economic advancement, as raising a child requires significant amounts of resources: time,[11] social, financial,[12] and environmental.[13] Planning can help assure that resources are available.

For many, the purpose of family planning is to make sure that any couple, man, or woman who has a child has the resources that are needed in order to complete this goal.[14] With these resources a couple, man or woman can explore the options of natural birth, surrogacy, artificial insemination, or adoption. In the other case, if the person does not wish to have a child at the specific time, they can investigate the resources that are needed to prevent pregnancy, such as birth control, contraceptives, or physical protection and prevention.

There is no clear social impact case for or against conceiving a child. Individually, for most people,[15] bearing a child or not has no measurable impact on personal well-being. A review of the economic literature on life satisfaction shows that certain groups of people are much happier without children:

- Single parents

- Fathers who both work and raise the children equally

- Singles

- The divorced

- The poor

- Those whose children are older than three

- Those whose children are sick[16]

However, both adoptees and the adopters report that they are happier after adoption.[17]

Resources

When women can pursue additional education and paid employment, families can invest more in each child. Children with fewer siblings tend to stay in school longer than those with many siblings. Leaving school in order to have children has long-term implications for the future of these girls, as well as the human capital of their families and communities. Family planning slows unsustainable population growth which drains resources from the environment, and national and regional development efforts.[13][18]

Health

The WHO states about maternal health that:

- "Maternal health refers to the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. While motherhood is often a positive and fulfilling experience, for too many women it is associated with suffering, ill-health and even death."

About 99% of maternal deaths occur in less developed countries; less than one half occur in sub-Saharan Africa and almost a third in South Asia.[20]

Both early and late motherhood have increased risks. Young teenagers face a higher risk of complications and death as a result of pregnancy.[20] Waiting until the mother is at least 18 years old before trying to have children improves maternal and child health.[21]

Also, if additional children are desired after a child is born, it is healthier for the mother and the child to wait at least two years (but not more than five years) after the previous birth before attempting to conceive.[21] After a miscarriage or abortion, it is healthier to wait at least six months.[21]

When planning a family, women should be aware that reproductive risks increase with the age of the woman. Like older men, older women have a higher chance of having a child with autism or Down syndrome; the chances of having multiple births increases, which cause further late-pregnancy risk; they have an increased chance of developing gestational diabetes; the need for a Caesarian section is greater; and the risk of prolonged labor is higher, putting the baby in distress.

Finances

Family planning is among the most cost-effective of all health interventions.[22] "The cost savings stem from a reduction in unintended pregnancy, as well as a reduction in transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV".[22]

Childbirth and prenatal health care cost averaged $7,090 for normal delivery in the United States in 1996.[23] U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that for a child born in 2007, a U.S. family will spend an average of $11,000 to $23,000 per year for the first 17 years of child's life.[11] (Total inflation-adjusted estimated expenditure: $196,000 to $393,000, depending on household income.)[11]

Investing in family planning has clear economic benefits and can also help countries to achieve their "demographic dividend", which means that countries productivity is able to increase when there are more people in the workforce and less dependents.[24] UNFPA says that "For every dollar invested in contraception, the cost of pregnancy-related care is reduced by $1.47."[24]

UNFPA states,

The lifetime opportunity cost related to adolescent pregnancy – a measure of the annual income a young mother misses out on over her lifetime – ranges from 1 per cent of annual gross domestic product in a large country such as China to 30 per cent of annual GDP in a small economy such as Uganda. If adolescent girls in Brazil and India were able to wait until their early twenties to have children, the increased economic productivity would equal more than $3.5 billion and $7.7 billion, respectively.[24]

In the Copenhagen Consensus produced by Nobel laureates in collaboration with the UN, universal access to contraception ranks as the third-highest policy initiative in social, economic, and environmental benefits for every dollar spent.[25] Providing universal access to sexual and reproductive health services and eliminating the unmet need for contraception will result in 640,000 fewer newborn deaths, 150,000 fewer maternal deaths and 600,000 fewer children who lose their mother. At the same time, societies will experience fewer dependents and more women in the workforce, driving faster economic growth. The costs of universal access to contraceptives will be about $3.6 billion/year, but the benefits will be more than $400 billion annually and maternal deaths will be reduced by 150,000.

Modern methods

Modern methods of family planning include birth control, assisted reproductive technology and family planning programs.

In regard to the use of modern methods of contraception, The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) says, "Contraceptives prevent unintended pregnancies, reduce the number of abortions, and lower the incidence of death and disability related to complications of pregnancy and childbirth."[24] UNFPA states, "If all women with an unmet need for contraceptives were able to use modern methods, an additional 24 million abortions (14 million of which would be unsafe), 6 million miscarriages, 70,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 infant deaths would be prevented."[24]

In cases where couples may not want to have children just yet, family planning programs help a lot. Federal family planning programs reduced childbearing among poor women by as much as 29 percent, according to a University of Michigan study.[26]

Adoption is another option used to build a family. There are seven steps that one must make towards adoption. One must decide to pursue an adoption, apply to adopt, complete an adoption home study, get approved to adopt, be matched with a child, receive an adoptive placement, and then legalize the adoption.[27]

Contraception

.JPG.webp)

A number of contraceptive methods are available to prevent unwanted pregnancy. There are natural methods and various chemical-based methods, each with particular advantages and disadvantages. Behavioral methods to avoid pregnancy that involve vaginal intercourse include the withdrawal and calendar-based methods, which have little upfront cost and are readily available. Long-acting reversible contraceptive methods, such as intrauterine device (IUD) and implant are highly effective and convenient, requiring little user action, but do come with risks. When cost of failure is included, IUDs and vasectomy are much less costly than other methods. In addition to providing birth control, male and/or female condoms protect against sexually transmitted diseases (STD). Condoms may be used alone, or in addition to other methods, as backup or to prevent STD. Surgical methods (tubal ligation, vasectomy) provide long-term contraception for those who have completed their families.[28]

Assisted reproductive technology

When, for any reason, a woman is unable to conceive by natural means, she may seek assisted conception. It is recommended to the couple to ask for reproductive counseling after one year of trying to conceive, or after six months of trying if the woman is more than 35 years old, if she has irregular or infrequent menses, if she has an history of endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease, or if a problem related to the male is present.

Some families or women seek assistance through surrogacy, in which a woman agrees to become pregnant and deliver a child for another couple or person (this is not allowed in all countries). There are two types of surrogacy: traditional and gestational. In traditional surrogacy, the surrogate uses her own eggs and carries the child for her intended parents. This procedure is done in a doctor's office through intrauterine insemination (IUI). This type of surrogacy obviously includes a genetic connection between the surrogate and the child. Legally, the surrogate will have to disclaim any interest in the child to complete the transfer to the intended parents. A gestational surrogacy occurs when the intended mother's or a donor egg is fertilized outside the body and then the embryos are transferred into the uterus. The woman who carries the child is often referred to as a gestational carrier. The legal steps to confirm parentage with the intended parents are generally easier than in a traditional because there is no genetic connection between child and carrier.[29]

Sperm donation is another form of assisted conception. It involves donated sperm being used to fertilise a woman's ova by artificial insemination (either by intracervical insemination or IUI) and less commonly by in vitro fertilization (IVF), but insemination may also be achieved by a donor having sexual intercourse with a woman for the purpose of achieving conception. This method is known as natural insemination (NI).

Mapping of a woman's ovarian reserve, follicular dynamics and associated biomarkers can give an individual prognosis about future chances of pregnancy, facilitating an informed choice of when to have children.[30]

Fertility awareness

Fertility awareness refers to a set of practices used to determine the fertile and infertile phases of a woman's menstrual cycle. These methods may be used to avoid pregnancy, to achieve pregnancy, or as a way to monitor gynecological health. Methods of identifying infertile days have been known since antiquity, but scientific knowledge gained during the past century has increased the number and variety of methods. Various methods can be used and the Symptothermal method has achieved success rates over 99% if used properly.[31]

These methods are used for various reasons: There are no drug-related side effects,[32] they are free to use and only have a small upfront cost, they work for both achieving and preventing pregnancy, and they may be used for religious reasons. (The Catholic Church promotes this as the only acceptable form of family planning, calling it Natural Family Planning.) Their disadvantages are that either abstinence or a backup contraception method is required on fertile days, typical use is often less effective than other methods,[33] and they do not protect against sexually transmitted infection.[34]

Media campaign

Recent research based on nationally representative surveys supports a strong association between family planning mass media campaigns and contraceptive use, even after controlling for social and demographic variables. The 1989 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey found half of the women who recalled hearing or seeing family planning messages in radio, print, and television consequently used contraception, compared with 14% who did not recall family planning messages in the media, even after age, residence and socioeconomic status were taken into account.[35]

The Health Education Division of the Ministry of Health conducted the Tanzanian Family Planning Communication Project from January 1991 through December 1994, a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).[35] The program intended to educate both men and men of reproductive age about modern contraception methods. The major media channels and products included radio spots, radio series drama, Green Star logo promotional activities (identifies sites where family planning services are available), posters, leaflets, newspapers, and audio cassettes. In conjunction with other non-project interventions sponsored by other Tanzanian and international agencies from 1992 to 1994, contraception use among women ages 15–49 increased from 5.9% to 11.3%. The total fertility rate dropped from 6.3 lifetime births per individual in 1991–1992 to 5.8 in 1994.

Providers

Direct government support

Direct government support for family planning includes providing family planning education and supplies through government-run facilities such as hospitals, clinics, health posts and health centers and through government fieldworkers.[36]

In 2013, 160 out of 197 governments provided direct support for family planning. Twenty countries only provided indirect support through private sector or NGOs. Seventeen governments did not support family planning. Direct government support has continued to increase in developing countries from 82% in 1996 to 93% in 2013, but is declining in developed countries from 58% in 1976 to 45% in 2013. Ninety-seven percent of Latin America and the Caribbean, 96% of Africa, and 94% of Oceania governments provided direct support for family planning. In Europe, only 45% of governments directly support family planning. Out of 172 countries with available data in 2012, 152 countries had implemented realistic measures to increase women's access to family planning methods from 2009 to 2014. This data included 95% of developing nations and 65% of developed nations.[36]

Private sector

The private sector includes nongovernmental and faith-based organizations that typically provide free or subsidized services to for-profit medical providers, pharmacies and drug shops. The private sector accounts for approximately two-fifths of contraceptive suppliers worldwide. Private organizations are able to provide sustainable markets for contraceptive services through social marketing, social franchising, and pharmacies.[37]

Social marketing employs marketing techniques to achieve behavioral change while making contraceptives available. By utilizing private providers, social marketing reduces geographic and socioeconomic disparities and reaches men and boys.[37]

Social franchising designs a brand for contraceptives in order to expand the market for contraceptives.[37]

Drug shops and pharmacies provide health care in rural areas and urban slums where there are few public clinics. They account for most of the private sector provided contraception in sub-Saharan Africa, especially for condoms, pills, injectables and emergency contraception. Pharmacy supply and low-cost emergency contraception in South Africa and many low-income countries increased access to contraception.[37]

Workplace policies and programs help expand access to family planning information. The Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia, which works with more than 150 enterprises to improve health services, analyzed health outcomes in one factory over 10 years and found reductions in unintended pregnancies and STIs as well as sick leave. Contraception use rose from 11% to 90% between 1997 and 2000. In 2016, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers Export Association partnered with family planning organizations to provide training and free contraceptives to factory clinics, creating the potential to reach thousands of factory employees.[37]

Non-governmental organizations

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) may meet the needs of local poor by encouraging self-help and participation, understanding social and cultural subtleties, and working around red tape when governments do not adequately meet the needs of their constituents. A successful NGO can uphold family planning services even when a national program is threatened by political forces. NGOs can contribute to informing government policy, developing programs, or carry out programs that the government will not or can not implement.[38]

International oversight

Family planning programs are now considered a key part of a comprehensive development strategy. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (now superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals) reflects this international consensus. The 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, hosted by the UK government and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, affirmed political commitments and increased funds for the project, strengthening the role of family planning in global development.[39] Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) is the result of the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning where more than 20 governments made commitments to address the policy, financing, delivery, and socio-cultural barriers to women accessing contraception formation and services. FP2020 is a global movement that supports the rights of women to decide for themselves whether, when and how many children they want to have.[40] The commitments of the program are specific to each country, as compared to the generalized main goals of the 1995 conference program of action. FP2020 is hosted by the United Nations Foundation and operates in support of the UN Secretary-General's Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health.

The world's largest international source of funding for population and reproductive health programs is the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). In 1994, the International Conference on Population and Development set the main goals of its Program of Action as:

- Universal access to reproductive health services by 2015

- Universal primary education and ending the gender gap in education by 2015

- Reducing maternal mortality by 75% by 2015

- Reducing infant mortality

- Increasing life expectancy at birth

- Reducing HIV infection rates in persons aged 15–24 years by 25% in the most-affected countries by 2005, and by 25% globally by 2010

The World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank estimate that $3 per person per year would provide basic family planning, maternal and neonatal health care to women in developing countries. This would include contraception, prenatal, delivery, and post-natal care in addition to postpartum family planning and the promotion of condoms to prevent sexually transmitted infections.[41]

Injustices and coercive interference with family planning

Inequities in family planning within the United States

Historically, the capacity to control one's reproductive abilities has been unequally distributed across society. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs), including intrauterine devices and progestin implants, and permanent sterilization have been implemented to limit reproduction in communities of color, the lower socioeconomic class, and among individuals with intellectual disabilities.[42] Multiple studies have reported disproportionate recommendations of LARCs to individuals from marginalized communities compared to white, high-income individuals.[43] With the eugenics movement of the 20th century, 60,000 people were sterilized in 32 states across the US with state-sanctioned sterilizations peaking in 1930-40's.[44] More recently, unwanted sterilizations have been performed on over a thousand women in California prisons between 1997 and 2010.[45] Protocols have been established to protect against unwanted permanent contraception through Medicaid Laws, but there has not been a widespread declaration by the Supreme Court ruling forced sterilization unconstitutional.[46]

Forced sterilization

Compulsory or forced sterilization programs or government policy attempt to force people to undergo surgical sterilization without their freely given consent. People from marginalized communities are at most risk of forced sterilization.[47] Forced sterilization has occurred in recent years in Eastern Europe (against Roma women),[47][48] and in Peru (during the 1990s against indigenous women).[49] China's one-child policy was intended to limit the rise in population numbers, but in some situations involved forced sterilisation.

Sexual violence

Rape can result in a pregnancy. Rape can occur in a variety of situations, including war rape, forced prostitution and marital rape.

In Rwanda, the National Population Office has estimated that between 2,000 and 5,000 children were born as a result of sexual violence perpetrated during the genocide, but victims' groups gave a higher estimated number of over 10,000 children.[50]

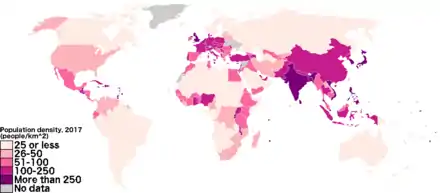

Human rights, development and climate

_per_capita_in_2019.svg.png.webp)

Some consider access to safe, voluntary family planning to be a human right and to be central to gender equality, women's empowerment and poverty reduction. Over the past 50 years, right-based family planning has enabled the cycle of poverty to be broken resulting in millions of women and children's lives being saved.[52]

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) says that "Some 225 million women who want to avoid pregnancy are not using safe and effective family planning methods, for reasons ranging from lack of access to information or services to lack of support from their partners or communities."[52] The UNFPA says that "Most of these women with an unmet need for contraceptives live in 69 of the poorest countries on earth."[52]

The UNFPA says,

Global consensus that family planning is a human right was secured at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, in Principle 8 of the Programme of Action: All couples and individuals have the basic right to decide freely and responsibly the number and spacing of their children and to have the information, education, and means to do so.[52]

As part of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) universal access to family planning is one of the key factors contributing to development and reducing poverty. Family planning creates benefits in areas such as, gender quality and women's health, access to sexual education and higher education, and improvements in maternal and child health.[52] Note that the Millennium Development Goals have been superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals.

UNFPA and the Guttmacher Institute say,

Serving all women in developing countries that currently have an unmet need for modern contraceptives would prevent an additional 54 million unintended pregnancies, including 21 million unplanned births, 26 million abortions and seven million miscarriages; this would also prevent 79,000 maternal deaths and 1.1 million infant deaths.[53]

Since climate change is directly proportional to the number of humans, family planning has a significant impact on climate change. The research project Drawdown estimates that family planning is the seventh most efficient action against climate change (ahead of solar farms, nuclear power, afforestation and many other actions).[54]

In a 2021 paper for Sustainability Science, William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf and Eileen Crist argue that population policies can both advance social justice, while at the same time mitigating the human impact on the climate and the earth system. They note that the richer half of the world's population is responsible for 90% of the CO2 emissions.[55]

Quality-quantity trade-off

Having children produces a quality-quantity trade-off: parents need to decide how many children to have and how much to invest in the future of each child.[56] The increasing marginal cost of quality (child outcome) with respect to quantity (number of children) creates a trade-off between quantity and quality.[57] The quantity-quality trade-off means that policies that raise benefits of investing in child quality will generate higher levels of human capital, and policies that lower the costs of having children may have unintended adverse consequences on long-run economic growth. When deciding how many children, parents are influenced by their income level, perceived return to human capital investment, and cultural norms related to gender equality. Controlling birth rates allows families to raise the future earnings power of the next generation. Many empirical studies have tested the quantity-quality trade-off and either observed a negative correlation between family size and child quality or did not find a correlation.[57] Most studies treat family size as an exogenous variable because parents choose childbearing and child outcome and therefore cannot establish causality. They are both influenced by typically non-observable parental preferences and household characteristics, but some studies observe proxy variables such as investment in education.

Developing countries

High fertility countries have 18% of the world's population but contribute 38% of the population growth.[58] In order to become rich, resources must be re-appropriated to increase income per person rather than supporting larger populations. As populations increase, governments must accommodate increasing investments in health and human capital and institutional reforms to address demographic divides. Reducing the cost of human capital can be implemented by subsidizing education, which raises the earning power of women and the opportunity cost of having children, consequently lowering fertility.[56] Access to contraceptives may also yield lower fertility rates: having more children than expected constrains the individual from attaining their desired level of investment in child quantity and quality.[56] In high fertility contexts, reduced fertility may contribute to economic development by improving child outcomes, reducing maternal mortality and increasing female human capital.

Dang and Rogers (2015) show that in Vietnam, family planning services increased investment in education by lowering the relative cost of child quality and encouraging families to invest in quality.[59] By observing the distance to the nearest family planning center and the general education expenditure on each child, Dang and Rogers provide evidence that parents in Vietnam are making a child quality-quantity trade-off.

Developed countries

Currently, developed countries have experienced rising economic growth and falling fertility. As a result of the demographic transition that takes place when countries become rich, developed countries have an increasing proportion of retired people which raises the burden on the workforce population to support pensions and social programs. Encouraging higher fertility as a solution may risk reversing the benefits for increased child investment and female labor force participation have had on economic growth. Increasing high skill migration may be an effective way to increase the return to education leading to lower fertility and a greater supply of highly skilled individuals.[56]

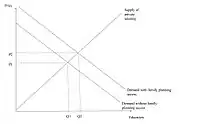

Demand for family planning

214 million women of reproductive age in developing countries who do not want to become pregnant are not using a modern contraceptive method.[61] This could be a result of a limited choice of methods, limited access to contraception, fear of side-effects, cultural or religious opposition, poor quality of available services, user or provider bias, or gender-based barriers. In Africa, 24.2% of women of reproductive age do not have access to modern contraction. In Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, the unmet need is 10–11%. Meeting the unmet need for contraception could prevent 104,000 maternal deaths per year, a 29% reduction of women dying from postpartum hemorrhage or unsafe abortions.[62]

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division, 64% of the world uses contraceptives, and 12% of the world population's need for contraceptives is unmet. In the least developed countries, 22% of the population do not have access to contraceptives, and 40% use contraceptives.[63] The unmet need for modern contraceptives is very high in sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia, and western Asia. Africa has the lowest rate of contraceptive use (33%) and highest rate of unmet need (22%). Northern America has the highest rate of contraceptive use (73%) and the lowest unmet need (7%). Latin America and the Caribbean follows closely behind with 73% contraceptive use and 11% unmet need. Europe and Asia are on par: Europe has a 69% contraceptive use rate and 10% unmet need, Asia has a 68% contraceptive use and 10% unmet need. Although unmet need is lower in Asia because of the large population in this region, the number of women with unmet need is 443 million, compared to 74 million in Europe Oceania has a 59% contraceptive use rate and 15% unmet need. When comparing the regions within these continents, Eastern Asia ranks the highest rate of contraceptive use (82%) and lowest unmet need (5%). Western Africa ranks the lowest rate of contraceptive use (17%). Middle Africa ranks the highest unmet need (26%). Unmet need is higher among poorer women; in Bolivia and Ethiopia unmet need is tripled and doubled among poor populations.[64] However, in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Liberia the rates of unmet need are different by 1–2 percentage points.[64] This suggests that as wealthier women begin to want smaller families, they will increasingly seek out family planning methods.[64]

Substantial unmet need has provoked family planning programs by governments and donors, but the impact of family planning programs on fertility and contraceptive use remains somewhat unsettled. "Demand theory" argues that in traditional agricultural societies, fertility rates are driven by the desire to offset high mortality, thus as society modernizes, the costs of raising children increases, reducing their economic value, and resulting in a decline in desired number of children. Under this theory, family planning programs will have a marginal impact. Bongaarts (2014) shows that using a country case study approach, both stronger and weaker family programs reduce the unmet need for contraceptives and increases use by making modern contraceptives more widely available and removing obstacles to use.[39] Also, the demand that is satisfied and the proportion of women using modern methods increased. The programs may have an additional effect of diffusing the ideas related to family planning and thus raising the demand for contraception. As a result, a small decrease in unmet need may be offset by a rise in demand. Nonetheless, even in countries where it is assumed that family programs will make a marginal impact, Bongaarts shows that family planning programs can potentially increase contraceptive use and increase/decrease demand depending on the preexisting attitudes of the community.

Regional variations

Africa

Most of the countries with lowest rates of contraceptive use, highest maternal, infant, and child mortality rates, and highest fertility rates are in Africa.[65][66][67][68][69] Only about 30% of all women use birth control, although over half of all African women would like to use birth control if it was available to them.[18][70] The main problems that preventing access to and use of birth control are unavailability, poor health care services, spousal disapproval, religious concerns, and misinformation about the effects of birth control.[18] The most available type of birth control is condoms.[71] A rapidly growing population coupled with an increase in preventable diseases means countries in Sub-Saharan Africa face an increasingly younger population.

China

China's Family planning policy forced couples to have no more than one child. Beginning in 1979 and being officially phased out in 2015,[72] the policy was instated to control the rapid population growth that was occurring in the nation at that time. With the rapid change in population, China was facing many impacts, including poverty and homelessness. As a developing nation, the Chinese government was concerned that a continuation of the rapid population growth that had been occurring would hinder their development as a nation. The process of family planning varied throughout China, as people differed in their responsiveness to the one-child policy, based on location and socioeconomic status. For example, many families in the cities accepted the policy more readily based on the lack of space, money, and resources that often occurs in the cities. Another example can be found in the enforcement of this rule; people living in rural areas of China were, in some cases, permitted to have more than one child, but had to wait several years after the birth of the first one.[73] However, the people in rural areas of China were more hesitant in accepting this policy. China's population policy has been credited with a very significant slowing of China's population growth which had been higher before the policy was implemented. However, the policy has come under criticism that it has resulted in abuse of women and girls. Often implementation of the policy has involved forced abortions, forced sterilization, and infanticides. In areas where family-planning regulations were strictly enforced like Guangxi Province, 80% of trafficked babies were girls as parents were more likely to sell their baby girls on the black market than baby boys. The number of girls that die within their first year of birth is twice that of boys.[74] Another drawback of the policy is that China's elderly population is now increasing rapidly.[75] However, while the punishment of "unplanned" pregnancy is a large fine, both forced abortion and forced sterilization can be charged with intentional assault, which is punished with up to ten years' imprisonment.

Family planning in China had its benefits, and its drawbacks. For example, it helped reduce the population by about 300 million people in its first 20 years.[76] A drawback is that there are now millions of sibling-less people, and in China siblings are very important. Once the parent generation gets older, the children help take care of them, and the work is usually equally split among the siblings.[77] Another benefit of the implementation of the one-child law is that it reduced the fertility rate from about 2.75 children born per woman, to about 1.8 children born per woman in the 1979.[78]

In 2015, China ended the one-child policy, announcing that all married couples will be allowed to have two children, in a bid to reverse the rapid aging of the labor force.[79] The one-child policy was replaced with a two-child policy.

In 2020, Chinese academics warn the country's leaders that the country's history of family planning have led to a decline in population growth. The decline in birthrate along with the increase in life expectancy could potentially mean that there will be too few workers to support the large aging population.[79]

In 2021, Chinese officials announced that a Chinese couple can now have three children, as the two-child policy failed to increase the country's declining birthrate.[80]

Xinjiang and the genocide of the Uyghur people

According to an investigative report by The Associated Press published 28 June 2020, the Chinese government is taking draconian measures to slash birth rates among Uyghurs and other minorities as part of a sweeping campaign to curb its Muslim population, even as it encourages some of the country's Han majority to have more children.[81] While individual women have spoken out before about forced birth control, the practice is far more widespread and systematic than previously known, according to an AP investigation based on government statistics, state documents and interviews with 30 ex-detainees, family members and a former detention camp instructor.

The ongoing oppression of the Uyghur people and the violence against their reproductive rights started in 2017 in the far west region of Xinjiang, and is leading to what some experts are calling a form of "demographic genocide".[81] In 2021, the Uyghur Tribunal in London concluded that China has subjected the Muslim minority to forced sterilizations and abortion approved by the highest level in Beijing.[82] Through their investigation they also found evidence that pregnant women were forced to have abortions even at the last stage of pregnancy.[82] Since 2017, births in China's Xinjiang regions have dropped sharply. Between 2015 and 2018, population growth in largely Uyghur areas fell by 84%.[83] This decline is not only attributed to the splitting of couples, but also mass sterilization policies and forced IUD implantation. Between 2014 and 2018, the rate of IUD placements increased by more than 60% in Xinjiang, while it dropped in other areas of China.[83] Uyghur survivors who have made it out of the concentration camps have reported and testified regarding the violence against reproductive rights in the camps. One survivor shares that she was given injections and kicked repeatedly in the stomach, and is no longer able to have children.[83] This is one of countless examples of the violence against women and their rights to family planning within the Uyghur concentration camps.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, the Eugenics League was founded in 1936, which became The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong in 1950.[84] The organisation provides family planning advice, sex education, birth control services to the general public of Hong Kong. In the 1970s, due to the rapidly rising population, it launched the "Two Is Enough" campaign, which reduced the general birth rate through educational means.[84]

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, Hong Kong's national family planning association,[85] founded the International Planned Parenthood Federation with its counterparts in seven other countries.[85]

India

Family planning in India is based on efforts largely sponsored by the Indian government. In the 1965–2009 period, contraceptive usage has more than tripled (from 13% of married women in 1970 to 48% in 2009) and the fertility rate has more than halved (from 5.7 in 1966 to 2.6 in 2009), but the national fertility rate is still high enough to cause long-term population growth. India adds up to 1,000,000 people to its population every 15 days.[86][87][88][89][90] However, forecasted growth rate may be inaccurate due to high disparities in education among Indian females and Indian states. An increase in education rates has been associated with a decline in the national fertility rate of India. As of 2015, the national fertility rate among Indian females is 2.2 children per female, which is approximately 3 times less than India's national fertility rate in the 1960s.[91] This shift in national fertility rate may also reflect a marked change in family planning practices within India.

India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare states that if adequate family planning access resources become available and accessible, India would reduce the number of infant deaths by 1,200,000.[92] Some of the most prevalent forms of contraception used in India today include sterilization, which is the most common method, followed by use of condoms and oral contraceptive pills.[93][94] However, the use of intrauterine devices (IUD's) remains markedly lower.[94]

There is also a wide variation in the demand for family planning services and methods in different Indian states, with Manipur having the lowest demand (23.6%) while Andhra Pradesh has the highest (93.6%).[94] Levels of social independence and attitudes towards domestic violence have been shown to influence demand for family planning services and resources. However, more research is necessary to determine other predictive factors to gauge demand for family planning.[94][93] Economic and cultural barriers also impede the delivery of family planning resources to all women on a national level.[95] A lack of cohesive infrastructure in developing countries poses one great hurdle to physically delivering oral contraceptives and medications to woman residing in non-urban areas. Additionally, the expensiveness of modern contraceptives limits women from regularly accessing these resources. Culturally, the use of contraceptives is discouraged and antagonized.[95] However, it is important to note that this sentiment varies greatly among castes, social classes, education status, and geographic location.[95]

Debate exists regarding the widespread acceptance of family planning practices within India. Some parties argue that longer life expectancy, coupled with lower birth rates, allow working-age individuals to accumulate more wealth since they need to support fewer dependents.[93] Conversely, other studies indicate that family planning can reduce the birth rate and cause the country's population to shrink. This debate has garnered national attention, and legislation has been passed and is being considered in the Indian Parliament to resolve these issues.

Iran

While Iran's population grew at a rate of more than 3% per year between 1956 and 1986, the growth rate began to decline in the late 1980s and early 1990s after the government initiated a major population control program. By 2007 the growth rate had declined to 0.7 percent per year, with a birth rate of 17 per 1,000 persons and a death rate of 6 per 1,000.[96] Reports by the UN show birth control policies in Iran to be effective with the country topping the list of greatest fertility decreases. UN's Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs says that between 1975 and 1980, the total fertility number was 6.5. The projected level for Iran's 2005 to 2010 birth rate is fewer than two.[97]

In late July 2012, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei described Iran's contraceptive services as "wrong", and Iranian authorities are slashing birth-control programs in what one Western newspaper (USA Today) describes as a "major reversal" of its long standing policy. Whether program cuts and high-level appeals for bigger families will be successful is still unclear.[98]

Ireland

The sale of contraceptives was illegal in Ireland from 1935 until 1980, when it was legalized with strong restrictions, later loosened. It has been argued that the resulting demographic dividend played a role in the economic boom in Ireland that began in the 1990s and ended abruptly in 2008 (the Celtic tiger) was in part due to the legalisation of contraception in 1979 and subsequent decline in the fertility rate.[99] In Ireland, the ratio of workers to dependents increased due to lower fertility—the reality of which has been questioned[100]—but was raised further by increased female labor market participation.

Pakistan

In agreement with the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, Pakistan pledged that by 2010 it would provide universal access to family planning. Additionally, Pakistan's Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper has set specific national goals for increases in family planning and contraceptive use.[101] In 2011 just one in five Pakistani women ages 15 to 49 uses modern birth control.[102] Contraception is shunned under traditional social mores that are fiercely defended as fundamentalist Islam gains strength.[102]

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012 guarantees universal access to methods on contraception, fertility control, sexual education, and maternal care. While there is general agreement about its provisions on maternal and child health, there is great debate on its mandate that the Philippine government and the private sector will fund and undertake widespread distribution of family planning devices such as condoms, birth control pills, and IUDs, as the government continues to disseminate information on their use through all health care centers.

Russia

According to a 2004 study, current pregnancies were termed "desired and timely" by 58% of respondents, while 23% described them as "desired, but untimely", and 19% said they were "undesired". As of 2004, the share of women of reproductive age using hormonal or intrauterine birth control methods was about 46% (29% intrauterine, 17% hormonal).[103] During the Soviet era high quality contraceptives were difficult to obtain, and abortion became the most common way of preventing unwanted births. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union abortion rates have fallen considerably, but they are still higher than rates in many developed countries.

Singapore

Population control in Singapore spans two distinct phases: first to slow and reverse the boom in births that started after World War II; and then, from the 1980s onwards, to encourage parents to have more children because birth numbers had fallen below replacement levels.

Thailand

In 1970, Thailand's government declared a population policy that would battle the country's rapid population growth rate. This policy set a five-year goal to reduce Thailand's population growth rate from 3 percent to 2.5 percent through methods such as spreading family planning awareness to rural families, or integrating family planning activities into maternal and child healthcare education.[104] Public figures such as Mechai Viravaidya helped spread family planning awareness through public speakings and charitable activities.

United Kingdom

Contraception has been available for free under the National Health Service since 1974, and 74% of reproductive-age women use some form of contraception.[105] The levonorgestrel intrauterine system has been massively popular.[105] Sterilization is popular in older age groups, among those 45–49, 29% of men and 21% of women have been sterilized.[105] Female sterilization has been declining since 1996, when the intrauterine system was introduced.[105] Emergency contraception has been available since the 1970s, a product was specifically licensed for emergency contraception in 1984, and emergency contraceptives became available over the counter in 2001.[105] Since becoming available over the counter it has not reduced the use of other forms of contraception, as some moralists feared it might.[105] In any year only 5% of women of childbearing age use emergency hormonal contraception.[105]

Despite widespread availability of contraceptives, almost half of pregnancies were unintended in 2005.[105] Abortion was legalized in 1967.[105]

United States

In the US, family planning is more expiclitly associated with contraception. It is defined as "the ability of individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility."[106]

Despite the availability of highly effective contraceptives, about half of U.S. pregnancies are unintended.[33] Highly effective contraceptives, such as IUD, are underused in the United States.[70] Increasing use of highly effective contraceptives could help meet the goal set forward in Healthy People 2020 to decrease unintended pregnancy by 10%.[70] Cost to the user is one factor preventing many American women from using more effective contraceptives.[70] Making contraceptives available without a copay increases use of highly effective methods, reduces unintended pregnancies, and may be instrumental in achieving the Healthy People 2020 goal.[70]

In the United States, contraceptive use saves about $19 billion in direct medical costs each year.[33] Title X of the Public Health Service Act,[107] is a U.S. government program dedicated to providing family planning services for those in need. But funding for Title X as a percentage of total public funding to family planning client services has steadily declined from 44% of total expenditures in 1980 to 12% in 2006. Current funding for Title X is less than 40% of what is needed to meet the need for publicly funded family planning.[108] Title X would need $737 million annually to meet the need for family planning services.[108] Only 6.2 million women accessed publicly funded services from 10,700 clinics in 2015, despite an estimated 20 million women who could benefit.

Clinics funded by Title X served 3.8 million of these women with access to services.In 2015, publicly funded contraceptive services helped women prevent 1.9 million unintended pregnancies; 876,100 of these would have resulted in unplanned births and 628,000 abortions.[109] Without publicly funded contraceptive services, the rates of unintended pregnancies, unplanned births and abortions would have been 67% higher.[109] The rates for teens would have been 102% higher.[109] Title X funded programs saw 1.2 million fewer patients in 2015 compared to 2010 as funding decreased by $31 million.[109] In 2015, an estimated 2.4 million additional women received Medicaid-funded contraceptive services from private doctors.[110]

Medicaid has increased from 20% to 71% from 1980 to 2006. In 2006, Medicaid contributed $1.3 billion to public family planning.[111] The $1.9 billion spent on publicly funded family planning in 2008 saved an estimated $7 billion in short-term Medicaid costs.[112] Such services helped women prevent an estimated 1.94 million unintended pregnancies and 810,000 abortions.[112]

About 3 out of 10 women in the United States have an abortion by the time they are 45 years old.[113]

A 2017 paper found that parents' access to family planning programs had a positive economic impact on their subsequent children: "Using the county-level introduction of U.S. family planning programs between 1964 and 1973, we find that children born after programs began had 2.8% higher household incomes. They were also 7% less likely to live in poverty and 12% less likely to live in households receiving public assistance. After accounting for selection, the direct effects of family planning programs on parents' incomes account for roughly two thirds of these gains."[114] A 2021 study found disparity among racial groups in the perceived quality of family planning care received, with white women (72%) more likely to rate their experience with their providers as excellent than Black (60%) and Hispanic women (67%).[115]

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, the government has pushed for uteruses to be removed from women in order to forcibly sterilize them.[116]

In transgender individuals

Overall, transgender and gender diverse individuals face multiple barriers to achieving family planning goals. This community experiences lack of access to reproductive health care settings where they feel accepted, safe, and understood; reproduction help; pregnancy care; and contraception.[117] A barrier that gets in the way of becoming parents is the cost involved with fertility preservation options. For example, the use of sperm cryopreservation in the United States is less than 5% while countries such as the Netherlands, Australia and Israel have higher rates; this may be the result of challenges navigating health insurance coverage.[118] According to a study, in the United States the national median initial bank fee and annual price of storage are $350 and $385 respectively.[119] For those looking for egg preservation, a study calculated that the median total cost (which includes egg freezing, egg thawing, and annual preservation fee) in United States was around $7,444, and the cumulative costs for one live birth of US$11,704 for an individual in the age groups ≤ 35 years.[120] Other common concerns that arise when seeking pregnancy include having to stop or delay of hormonal therapy, worsening of gender dysphoria with treatment related to pregnancy.[121]

Interventions used to facilitate gender transition such as hormone therapy and gender affirming surgeries (e.g., genital surgery, and chest surgery) can temporarily or permanently impact the chance of becoming pregnant.[118][122] The World Professional Organization for Transgender Health (WPATH) and American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRMA) recommend offering counseling on the impact on family planning and transitioning to all transgender individuals [123] Even though many transgender and gender-nonbinary youth express desire to receive fertility counseling and recommendations from professional organization, studies indicate that only a small portion have these conversations with their health care team.[118] Health care professionals attribute lack of knowledge of reproductive health in this community, knowledge limitation due to lack of data on long term effects of hormonal intervention to the inconsistency in discussion around family building [118]

Studies have shown that transgender men can still become pregnant even in the absence of menstruation caused by gendered affirming therapy in the form of testosterone.[124] Inconsistent hormonal therapy such as missed doses, incomplete dosing, or switching therapy regimen, mostly due to barriers noted earlier, may also lead to breakthrough ovulation which can contribute to increase chances of unintended pregnant,[124] highlighting the need of contraception on transgender men (who have conserved reproductive organs) on testosterone if pregnancy is not desired.[124] Furthermore, testosterone can cause abnormal vaginal development in female fetuses (especially in the first trimester of pregnancy), becoming a concern for transgender men who conceived while on hormone therapy. Moreover, condoms are one of the most common contraceptive methods in transgender men, while another subset report no contraception use which can lead to unintended pregnancies. Some challenges to adopting a form of family planning method among this population varies depending on the method. For instance, fear of prevention of masculinization with use of estrogen-based contraceptives, and gender dysphoria with the use of contraceptive devises inside cervical/pelvic cavity.[125] Additionally, negative experiences in the health care system related to gender identity, and denial of health care based on gender identity makes it difficult for this community to access health care and family planning resources.[124]

Obstacles to family planning

There are many reasons as to why women do not use contraceptives. These reasons include logistical problems, scientific and religious concerns, limited access to transportation in order to access health clinics, lack of education and knowledge, and opposition by partners, families or communities.

The UNFPA states, "Poorer women and those in rural areas often have less access to family planning services. Certain groups — including adolescents, unmarried people, the urban poor, rural populations, sex workers and people living with HIV also face a variety of barriers to family planning. This can lead to higher rates of unintended pregnancy, increased risk of HIV and other STIs, limited choice of contraceptive methods, and higher levels of unmet need for family planning."[24]

For national, international, or local health programs involved in family planning, the use of standard indicators[126] is increasingly encouraged, to track barriers to effective family planning along with the efficacy, uptake, and provision of family planning services.[127]

COVID-19

As of March 2020, there were an estimated 450 million women using modern contraceptives across 114 priority low- and middle-income countries. The COVID-19 pandemic as well as social distancing and other strategies to reduce transmission are anticipated to impact the ability of these women to continue using contraception. The number of unintended pregnancies will increase as the lockdown continues and services disruptions are extended.[128]

Some 47 million women in 114 low- and middle-income countries are projected to be unable to use modern contraceptives if the average lockdown, or COVID-19-related disruption, continues for six months with major disruptions to services. For every three months the lockdown continues, assuming high levels of disruption, up to 2 million additional women may be unable to use modern contraceptives. If the lockdown continues for six months and there are major service disruptions due to COVID-19, an additional 7 million unintended pregnancies are expected to occur.[128]

World Contraception Day

September 26 is designated as World Contraception Day, devoted to raising awareness of contraception and improving education about sexual and reproductive health, with a vision of "a world where every pregnancy is wanted".[129] It is supported by a group of international NGOs, including:

Asian Pacific Council on Contraception, Centro Latinamericano Salud y Mujer, European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health, German Foundation for World Population, International Federation of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, International Planned Parenthood Federation, Marie Stopes International, Population Services International, The Population Council, The USAID, Women Deliver.[129]

Abortion

The United Nations Population Fund explicitly states it "never promotes abortion as a form of family planning."[5] The World Health Organization states that "Family planning/contraception reduces the need for abortion, especially unsafe abortion."[18]

The campaign to conflate contraception and abortion is rooted on the assertion that contraception ends, rather than prevents, pregnancy. This is due to the notion that preventing implantation implies an abortion, when considering fertilization as the initial moment of pregnancy. According to an amicus brief submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court in October 2013 led by Physicians for Reproductive Health and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a contraceptive method prevents pregnancy by interfering with fertilization, or implantation. Abortion, separate from contraceptives, ends an established pregnancy.[130]

See also

- Natural family planning

- Natalism and antinatalism

- Parental leave

- Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis for avoiding birth defects

- POPLINE (World's largest reproductive health database)

- Sex selection

- Human overpopulation

- Human population planning

- Birth in Sri Lanka

- Women in Bolivia

- Birth in Benin

- Opata people

- Pledge two or fewer (campaign for smaller families)

- Reproductive coercion

International organizations

- International Planned Parenthood Federation

- MSI Reproductive Choices

- Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition

- MEASURE Evaluation

National organizations

- British Pregnancy Advisory Service

- Family Planning Association India

- Family Planning Association of Hong Kong

- German Foundation for World Population (DSW)

- National Alliance for Optional Parenthood (USA)

- Planned Parenthood (USA)

References

- McKissack, Patricia; McKissack, Fredrick (1995). The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay Life in Medieval Africa. Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8050-4259-7.

- "What services do family planning clinics provide?". NHS. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System Glossary" (PDF). Administration for Children & Families. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Sexual and Reproductive Health. Retrieved on 30 October 2019.

- United Nations Population Fund. "Family planning". Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Bajos, N.; Le Guen, M.; Bohet, A.; Panjo, Henri; Moreau, C. (2014). "Effectiveness of family planning policies: The abortion paradox". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e91539. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...991539B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091539. PMC 3966771. PMID 24670784.

- Packham, Analisa (2017-09-01). "Family planning funding cuts and teen childbearing". Journal of Health Economics. 55: 168–185. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.07.002. ISSN 0167-6296. PMID 28811119.

- Kearney, M. S.; Levine, P. B. (2015). "Investigating recent trends in the U.S. teen birth rate". Journal of Health Economics. 41: 15–29. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.01.003. PMID 25647142.

- Lu, Yao; Slusky, David J. G. (2018-06-28). "The Impact of Women's Health Clinic Closures on Fertility" (PDF). American Journal of Health Economics. 5 (3): 334–359. doi:10.1162/ajhe_a_00123. ISSN 2332-3493. S2CID 51813993.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). "Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care — United States: A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the select panel on Preconception Care" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 55 (RR-6).

- Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. "Expenditures on Children by Families, 2007; Miscellaneous Publication Number 1528-2007". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "MsMoney.com - Marriage, Kids & College - Family Planning". www.msmoney.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008.

- Wynes, S.; Nicholas, K.A. (2017). "The climate mitigation gap: Education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (7): 074024. Bibcode:2017ERL....12g4024W. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541. ISSN 1748-9326.

- "Office of Family Planning". California Department of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08.

- Powdthavee, N. (n.d.). "Think having children will make you happy?". The British Psychological Society. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- "Linköping University" (PDF). www.iei.liu.se. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- "92 percent of families with adopted children are satisfied with their decision".

- World Health Organization (2018). "Family planning/Contraception". World Health Organization Newsroom. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Country Comparison: Maternal Mortality Rate Archived 2015-04-18 at the Wayback Machine in The CIA World Factbook.

- "Maternal mortality". World Health Organization.

- "Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy: HTSP Messages". USAID. Archived from the original on 2018-10-04. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- Tsui, A. O; McDonald-Mosley, R; Burke, A. E (2010). "Family Planning and the Burden of Unintended Pregnancies". Epidemiologic Reviews. 32: 152–74. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq012. PMC 3115338. PMID 20570955.

- Mushinski, M (1998). "Average charges for uncomplicated vaginal, cesarean and VBAC deliveries: Regional variations, United States, 1996". Statistical Bulletin. 79 (3): 17–28. PMID 9691358.

- "Family planning". www.unfpa.org.

- "Health - Women & Children | Copenhagen Consensus Center". www.copenhagenconsensus.com. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Family planning: Federal program reduced births to poor women by nearly 30 percent". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- "How to Adopt". Adoption Exchange Association. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "Birth control methods fact sheet". Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- "What is a Surrogate Mother or Gestational Carrier?". Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Nelson, S.M; Telfer, E.E; Anderson, R.A (2013). "The ageing ovary and uterus: New biological insights". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms043. PMC 3508627. PMID 23103636.

- Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; et al. (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2: Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States Archived 2017-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Manhart, Michael D; Duane, Marguerite; Lind, April; Sinai, Irit; Golden-Tevald, Jean (2013). "Fertility awareness-based methods of family planning: A review of effectiveness for avoiding pregnancy using SORT". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5: 2–8. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2012.09.002.

- Trussell, James; Lalla, Anjana M; Doan, Quan V; Reyes, Eileen; Pinto, Lionel; Gricar, Joseph (2009). "Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States". Contraception. 79 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003. PMC 3638200. PMID 19041435.

- "Fertility Awareness Method". Brown University Health Education Website. Brown University. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- "The Impact of Multimedia Family Planning Promotion On the Contraceptive Behavior of Women in Tanzania". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-07-11. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014). Abortion Policies and Reproductive Health around the World (PDF) (Report). United Nations.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Karen Hardee (Population Council), David Wofford (Meridien Group International), Nandita Thatte (World Health Organization), "Family Planning Evidence Briefs" prepared for the Family Planning Summit held in London on July 11, 2017. Published: World Health Organization, 2017.https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/FP2020_brief_private_sector_FINAL_07.10.17.pdf

- Lubin, D (1987). "Role of voluntary and non-governmental organizations in the national family planning programme". Population Manager: ICOMP Review. 1 (2): 49–52. PMID 12283526.

- Bongaarts, John (2014). "The Impact of Family Planning Programs on Unmet Need and Demand for Contraception". Studies in Family Planning. 45 (2): 247–62. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00387.x. PMID 24931078.

- "Family Planning 2020". www.familyplanning2020.org. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Promises to Keep: The Toll of Unintended Pregnancies on Women's Lives in the Developing World". Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Kramer, Renee D.; Higgins, Jenny A.; Godecker, Amy L.; Ehrenthal, Deborah B. (May 2018). "Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of long-acting reversible contraceptive use in the United States, 2011–2015". Contraception. 97 (5): 399–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.006. ISSN 0010-7824. PMC 5965256. PMID 29355492.

- Higgins, Jenny A.; Kramer, Renee D.; Ryder, Kristin M. (November 2016). "Provider Bias in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) Promotion and Removal: Perceptions of Young Adult Women". American Journal of Public Health. 106 (11): 1932–1937. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303393. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5055778. PMID 27631741.

- "Forced sterilization policies in the US targeted minorities and those with disabilities – and lasted into the 21st century". ihpi.umich.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Washington, Shilpa Jindia in (2020-06-30). "Belly of the Beast: California's dark history of forced sterilizations". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Manas, Kimberly. "Could Forced Sterilization Still be Legal in the US?". Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- http://www.stopvaw.org/forced_coerced_sterilization%5B%5D%5B%5D

- "Czech regret over sterilisation". 24 November 2009.

- Cabitza, Mattia (6 December 2011). "Peru women fight for justice over forced sterilisation". BBC News.

- Mukangendo, Marie Consolée (2007). "Caring for Children Born of Rape in Rwanda". In Carpenter, R. Charli (ed.). Born of War: Protecting Children of Sexual Violence Survivors in Conflict Zones. Kumarian Press. pp. 40–52. ISBN 9781565492370.

- Data from the United Nations is used.

- Choices not chance UNFPA

- Family planning, health and development UNFPA

- "FAMILY PLANNING". Drawdown. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Oregon State University (2021-04-28). "Socially just population policies can mitigate climate change and advance global equity". phys.org. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- Gregory Casey and Oded Galor, "Population and Demography Perspective Paper" Copenhagen Consensus Center, Post-2015 Consensus, October 3, 2014. http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/population_and_demography_perspective_-galor_casey.pdf

- Li, H; Zhang, J; Zhu, Y (2008). "The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: Identification using Chinese twins". Demography. 45 (1): 223–43. doi:10.1353/dem.2008.0006. PMC 2831373. PMID 18390301.

- "Post-2015 Consensus: Population and Demography Assessment, Kohler Behrman | Copenhagen Consensus Center". www.copenhagenconsensus.com. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- Dang, Hai-Anh H.; Rogers, F. Halsey (August 2015). "The Decision to Invest in Child Quality over Quantity: Household Size and Household Investment in Education in Vietnam" (PDF). The World Bank Economic Review. 30: 104–142 – via The World Bank.

- "Demand for family planning satisfied by modern methods". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Family planning/Contraception". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on April 18, 2011. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Universal Access to Contraception". www.apha.org. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division, "Trends in Contraceptive Use Worldwide 2015" New York: United Nations, 2015. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/trendsContraceptiveUse2015Report.pdf

- "Fact Sheet: Unmet Need for Family Planning". www.prb.org. Archived from the original on 2018-03-03. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- "Birth rate, crude (per 1,000 people)". World Bank. 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Contraceptive prevalence, any methods (% of women ages 15-49)". World Bank. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births)". World Bank. 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Fertility rate, total (births per woman)". World Bank. 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births)". World Bank. 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Cleland, K.; Peipert, J. F.; Westhoff, C.; Spear, S.; Trussell, J. (May 2011). "Family Planning as a Cost-Saving Preventive Health Service". New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (18): e37. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1104373. PMID 21506736.

- DeRose, Laurie; F. Nii-Amoo Dodoo; Alex C. Ezeh; Tom O. Owuor (June 2004). "Does Discussion of Family Planning Improve Knowledge of Partner's Attitude Toward Contraceptives?". Guttmacher Institute.

- Kane, P; Choi, C. Y (1999). "China's one child family policy". BMJ. 319 (7215): 992–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7215.992. PMC 1116810. PMID 10514169.

- Chan, Elaine (2005). Cultures of the World China. Marshall Cavendish International.

- "Infanticides in China". All Girls Allowed. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- "Today's Research on Aging" (PDF). prb.org/. Population Reference Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- FlorCruz, Jaime (27 September 2010). "China copes with promise and perils of one child policy". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- Rosseberg, Matt. "China's One Child Policy". About.com. Retrieved Feb 4, 2014.

- Lin, Zhimin (2006). China Under Reform. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers.

- Goldman, Russell (2021-05-31). "From One Child to Three: How China's Family Planning Policies Have Evolved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- Wee, Sui-Lee (2021-05-31). "China Says It Will Allow Couples to Have 3 Children, Up From 2". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- AP's global investigative team (28 June 2020). "China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization". The Associated Press. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Dyer, Clare (2021-12-20). "China forced Muslims in Xinjiang to be sterilised and have abortions, concludes tribunal". BMJ. 375: n3124. doi:10.1136/bmj.n3124. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 34930752. S2CID 245330194.

- Samuel, Sigal (2021-03-10). "China's genocide against the Uyghurs, in 4 disturbing charts". Vox. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- "History of the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong". Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- "History of International Planned Parenthood Federation". Archived from the original on August 13, 2009.

- Rabindra Nath Pati (2003). Socio-cultural dimensions of reproductive child health. APH Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-81-7648-510-4.

- Marian Rengel (2000), Encyclopedia of birth control, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 1-57356-255-6,

... In 1997, 36% of married women used modern contraceptives; in 1970, only 13% of married women had ...

- India and Family Planning: An Overview (PDF), Department of Family and Community Health, World Health Organization, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-21, retrieved 2009-11-25

- G.N. Ramu (2006), Brothers and sisters in India: a study of urban adult siblings, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-9077-X

- Arjun Adlakha (April 1997), Population Trends: India (PDF), U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-10, retrieved 2009-12-05

- KC, Samir; Wurzer, Marcus; Speringer, Markus; Lutz, Wolfgang (2018-08-14). "Future population and human capital in heterogeneous India". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (33): 8328–8333. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.8328K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1722359115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6099904. PMID 30061391.

- "MoHFW | Home". www.mohfw.gov.in. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- Muttreja, Poonam; Singh, Sanghamitra (December 2018). "Family planning in India: The way forward". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 148 (Suppl 1): S1–S9. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2067_17 (inactive 2022-09-24). ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 6469373. PMID 30964076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2022 (link) - Ewerling, Fernanda; McDougal, Lotus; Raj, Anita; Ferreira, Leonardo Z.; Blumenberg, Cauane; Parmar, Divya; Barros, Aluisio J. D. (2021-08-21). "Modern contraceptive use among women in need of family planning in India: an analysis of the inequalities related to the mix of methods used". Reproductive Health. 18 (1): 173. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01220-w. ISSN 1742-4755. PMC 8379729. PMID 34419083.

- Ghule, Mohan; Raj, Anita; Palaye, Prajakta; Dasgupta, Anindita; Nair, Saritha; Saggurti, Niranjan; Battala, Madhusudana; Balaiah, Donta (2015). "Barriers to use contraceptive methods among rural young married couples in Maharashtra, India: Qualitative findings". Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities. 5 (6): 18–33. doi:10.5958/2249-7315.2015.00132.X. ISSN 2250-1665. PMC 5802376. PMID 29430437.

- MSN Encarta Encyclopedia entry on Iran - People and Society Archived 2009-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, CIA World factbook 2007. Archived 2009-10-31.

- Iran tops world in birth control, payvand.com 04/17/09, access-date = 2010-03-23

- Iran urges baby boom, slashes birth-control programs usatoday.com 30 July 2012

- Bloom, David E.; Canning, David (2003). "Contraception and the Celtic Tiger" (PDF). Economic and Social Review. 34: 229–247. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-17.

- O'Brien, Carl (19 December 2011). "ESRI says fertility rate is greatly underestimated". The Irish Times.

- Hardee, Karen; Leahy, Elizabeth (2007). "Population, Fertility and Family Planning in Pakistan: A Program in Stagnation". Population Action International. 4 (1): 1–12. Archived from the original on 2013-04-26.

- Brulliard, Karin (15 December 2011). "As Pakistan's population soars, contraceptives remain a hard sell". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 April 2012.