Garden City, Kansas

Garden City is a city in, and the county seat of, Finney County, Kansas, United States.[2] As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 28,151.[4][5] The city is home to Garden City Community College and the Lee Richardson Zoo, the largest zoological park in western Kansas.

Garden City, Kansas | |

|---|---|

City and county seat | |

Historic Windsor Hotel, the Garden City Ampitheater, the Depot Monument, Eat Beef Sign, Historic State Theatre | |

| Nickname(s): GCK, The Beef Empire[1] | |

Location within Finney County and Kansas | |

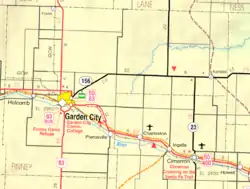

KDOT map of Finney County (legend) | |

| Coordinates: 37°58′31″N 100°51′51″W[2] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Finney |

| Founded | 1878 |

| Incorporated | 1883 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.93 sq mi (28.32 km2) |

| • Land | 10.91 sq mi (28.26 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.06 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,838 ft (865 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 28,151 |

| • Density | 2,600/sq mi (990/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 67846, 67868 |

| Area code | 620 |

| FIPS code | 20-25325[2] |

| GNIS ID | 471609[2] |

| Website | garden-city.org |

History

In February 1878, James R. Fulton, William D. Fulton and W.D.'s son, L.W. Fulton, arrived at the present site of Garden City.[6]

The original townsite was laid out on the south half of section 18 by engineer Charles Van Trump. The land was a loose, sandy loam and covered with sagebrush and soap weeds, but there were no trees. Main Street ran directly north and south, dividing William D. and James R. Fulton's claims. As soon as they could get building material, they erected two frame houses. William D. Fulton building on his land, on the east side of Main Street, a house one story and a half high, with two rooms on the ground and two rooms above. This was called the Occidental Hotel. William D. Fulton was proprietor. No other houses were built in Garden City until November 1878, when James R. Fulton and L.T. Walker each put up a building. The Fultons tried to get others to settle here, but only a few came, and at the end of the first year there were only four buildings.[6]

Following a sustained drought, irrigation arrived in Finney County in 1879, with completion of the "Garden City Ditch". The ditch helped to launch an agricultural boom in southwestern Kansas.[7]

19th century

Charles Jesse Jones, later known as "Buffalo" Jones, arrived in Garden City for an antelope hunt in January 1879. Before Jones returned home, the Fulton brothers procured his services to promote Garden City, and especially in trying to influence the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad to put in a switch station. The railroad agreed to place its station at Garden City. In the spring of 1879, more people began arriving to homestead in the area. During the years of 1885–1887, a rush was made for Western Kansas, and a settler arrived for every quarter section. The United States Land Office also located at Garden City, and people went there to make filings on their land. Lawyers also arrived in Garden City. I.R. Holmes, the agent for the sale of lands of the ATSF, and Holmes' partner, A.C. McKeever, in 1885 sold thousands of acres of railroad and private land.[6]

The streets of Garden City were crowded with horses, wagons, buggies and teams of oxen. Long lines of people stood out in the weather awaiting mail at the post office, and there was always a crowd in front of the land office. During the height of the boom the town had nine lumber yards. Lumber was hauled in all directions to build up inland towns and to improve the nearby homesteads. Thirteen drug stores were in operation, and the town had two daily newspapers. Nearly everyone used kerosene lamps, and a few were placed on posts on Main Street. There was no city water works, so all depended on shallow wells, which were strongly alkaline. Passenger trains of two and three sections arrived daily, loaded with people, most of whom got off at Garden City.[6]

The first issue of The Garden City Newspaper appeared April 3, 1879. Three months after the paper was established, the editor stated, "There are now forty buildings in town." When the first telephone line was built, trees were growing on both sides of Main Street. These interfered with the wires, but local residents knew the value of trees in Western Kansas would not allow them to be cut, and the telephone poles were set down the center of the street. The first long-distance telephone service from Garden City was a line nine miles (14 km) long, built in 1919.

20th century

In the 1970s, Garden City's city council allowed the building of a meatpacking plant. This invigorated the economy. New residents arrived, but even with population growth the unemployment rate was only about 3% in 2017. Many of the new arrivals were immigrants from outside the United States (Myanmar, Somalia, Vietnam, and other places, particularly Mexico and Latin America), such that over 48% of the 2010 population was Hispanic,[8] and less than 40% of the population was non-Hispanic white.[9]

21st century

In October 2016, Gavin Wright, Curtis Allen, and Patrick Stein were arrested by the FBI for plotting a bombing attack on a mosque and the housing complex where it resides in part of the town's Somali community.[10] The three men were charged in federal court with threatening to use weapons of mass destruction, namely explosives.[11][12][13] All three defendants were found guilty in April, 2018 and were sentenced to 25–30 years in prison.[14]

Geography

Garden City is at 37°58′31″N 100°51′51″W at an elevation of 2,838 feet (865 m).[2] Located in southwestern Kansas at the intersection of U.S. Route 50 and U.S. Route 83, Garden City is 192 miles (309 km) west-northwest of Wichita, 204 miles (328 km) north-northeast of Amarillo, and 255 miles (410 km) southeast of Denver.[15][16]

The city lies on the north side of the Arkansas River in the High Plains region of the Great Plains.[15]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.82 square miles (22.84 km2), all land.[17]

Climate

Garden City has a semi-arid steppe climate (Köppen: BSk) with hot, dry summers and cold, dry winters.[18] On average, January is the coldest month, July is the hottest month, and June is the wettest month.[19]

The average temperature in Garden City is approximately 54.2 °F or 12.3 °C.[20] Over the course of a year, temperatures range from an average low of 17.7 °F (−7.9 °C) in January to an average high of 91.8 °F (33.2 °C) in July. The high temperature reaches or exceeds 90 °F (32.2 °C) an average of 66 afternoons a year and reaches or exceeds 100 °F (37.8 °C) an average of eleven afternoons per year. The minimum temperature falls below the freezing point on an average of 138 mornings per year and to or below 0 °F (−17.8 °C) on five mornings each year. The hottest temperature recorded in Garden City was 110 °F (43.3 °C) as recently as June 8, 1985; the coldest temperature recorded was −22 °F (−30 °C) on March 11, 1948.[21]

Garden City receives 19.47 inches (495 mm) of precipitation during an average year with the largest share being received from May through August.[21] The average relative humidity is 62%.[20] There are, on average, 72 days of measurable precipitation each year. Annual snowfall averages 24.1 inches (61 cm). Measurable snowfall occurs an average of 8.5 days a year with at least one inch (2.5 cm) of snow being received on six of those days. Snow depth of at least an inch occurs an average of 19.5 days a year. The first fall freeze typically occurs by the second week of October, and the last spring freeze occurs by the last week of April.[21] Garden City is located in Tornado Alley and receives a share of storms every spring. On June 23, 1967, an F3 tornado struck the north side of Garden City, killing one person and damaging more than 400 homes.[22] On the days of April 30–May 1, 2017, the town was hit by a late-spring snowstorm which caused power outages and damaged almost every tree in town. Many tree limbs and some trees were downed because of it and the women's clinic had its roof collapse into the building, ultimately leading to its demolition in 2018.

| Climate data for Garden City, Kansas | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

100 (38) |

106 (41) |

110 (43) |

110 (43) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

97 (36) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

74 (23) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

98 (37) |

91 (33) |

77 (25) |

69 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 44.1 (6.7) |

48.2 (9.0) |

57.8 (14.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

76.5 (24.7) |

86.0 (30.0) |

91.8 (33.2) |

89.7 (32.1) |

82.0 (27.8) |

69.6 (20.9) |

55.6 (13.1) |

44.5 (6.9) |

67.8 (19.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.9 (−0.6) |

34.8 (1.6) |

43.6 (6.4) |

53.0 (11.7) |

63.3 (17.4) |

72.8 (22.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

76.7 (24.8) |

68.2 (20.1) |

55.4 (13.0) |

41.7 (5.4) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

54.2 (12.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.7 (−7.9) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

38.6 (3.7) |

50.1 (10.1) |

59.7 (15.4) |

64.6 (18.1) |

63.7 (17.6) |

54.3 (12.4) |

41.2 (5.1) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

40.6 (4.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

2 (−17) |

9 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

35 (2) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

38 (3) |

26 (−3) |

11 (−12) |

0 (−18) |

−8 (−22) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−17 (−27) |

−22 (−30) |

10 (−12) |

25 (−4) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

46 (8) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−5 (−21) |

−17 (−27) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.34 (8.6) |

0.54 (14) |

1.46 (37) |

1.72 (44) |

2.88 (73) |

3.48 (88) |

2.78 (71) |

2.45 (62) |

1.47 (37) |

1.28 (33) |

0.55 (14) |

0.52 (13) |

19.47 (494.6) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.6 (14) |

3.6 (9.1) |

5.9 (15) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

2.8 (7.1) |

3.7 (9.4) |

24.1 (60.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.1 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 72.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 8.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64 | 62 | 61 | 59 | 66 | 59 | 62 | 65 | 58 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 62 |

| Source: National Weather Service;[21] Weatherbase[20] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

There is a Main Downtown and Commercial Downtown.

- Main Downtown is centered on Southern Main Street. The Windsor Hotel and the police station are among the tallest buildings, and there are many other historic buildings in the area. Most of the businesses in the main downtown area are locally owned and operated.

- Commercial Downtown is centered mainly on East Kansas Avenue and on LaRue Road. It is the home of many businesses such as Menards, Wal-Mart, Sam's Club, Target, Dollar Tree, Staples, Home Depot, Hibbett Sports, Harbor Freight, TJ Maxx, Dick's Sporting Goods, PetCo, GameStop, Applebee's, Old Navy, Ross Dress For Less, and IHOP.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 1,490 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,590 | 6.7% | |

| 1910 | 3,171 | 99.4% | |

| 1920 | 3,848 | 21.3% | |

| 1930 | 6,121 | 59.1% | |

| 1940 | 6,285 | 2.7% | |

| 1950 | 10,905 | 73.5% | |

| 1960 | 11,811 | 8.3% | |

| 1970 | 14,790 | 25.2% | |

| 1980 | 18,256 | 23.4% | |

| 1990 | 24,097 | 32.0% | |

| 2000 | 28,451 | 18.1% | |

| 2010 | 26,658 | −6.3% | |

| 2020 | 28,151 | 5.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2010-2020[5] | |||

As of the 2010 census,[8] there were 26,658 people, 9,071 households, and 6,355 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,136.2 people per square mile (1,210.9/km2). There were 9,656 housing units at an average density of 1,136.0 per square mile (436.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 74.7% White, 4.4% Asian, 2.8% African American, 0.9% American Indian, 14.2% from some other race, and 2.9% from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race comprised 48.6% of the population.[23]

There were 9,071 households, of which 43.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.6% were married couples living together, 6.5% had a male householder with no wife present, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.9% were non-families. 24.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 19.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.88, and the average family size was 3.45.[23]

The median age was 29.9 years. 31.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.6% were between ages 18 and 24; 26.0% were between 25 and 44; 22.2% were between 45 and 64; and 9.0% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the population was 49.8% male and 50.2% female.[23]

The median income for a household in the city was $47,975, and the median income for a family was $54,621. Males had a median income of $33,873 versus $27,304 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,066. About 7.1% of families and 12.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.5% of those under age 18 and 6.0% of those age 65 or over.[23]

Ethnic groups

In 2017, Albert Kyaw, a translator of the Garden City Public Schools, stated that Garden City was the most ethnically diverse community in the state of Kansas. That year, according to Frank Morris of National Public Radio, "some say" the residents may speak up to 40 different languages; at least 27 were spoken.[24]

Hispanics and Latinos, including immigrants, came to Garden City beginning in the 1980s due to the establishment of meatpacking plants and partially due to plant management deliberately recruiting them. Many educational institutions for adults were teaching Hispanic immigrants after they had asked for amnesty for having illegally immigrated.[25]

After the Fall of Saigon in 1975 immigrants from Southeast Asia began coming to Garden City. Garden City Catholics sponsored an initial group of Vietnamese immigrants that year. More Vietnamese came in the 1980s during a wave of immigration, and Lao people also came with them. Dr. Janet E. Benson of Kansas State University stated that perhaps about half had originated from Wichita since they had lost work during industry layoffs there. The second group of Vietnamese were less educated than the first, and they were more likely to be Buddhist as opposed to being Christian. In their home country they had originally done agricultural and/or fishing work. By the late 1980s many Mexican immigrants replaced Vietnamese immigrants who had moved away from Garden City and stopped doing meatpacking work since they had made sufficient money.[25]

Economy

The economy of Garden City is driven largely by agriculture. There are several feedlots and grain elevators located in and around the city. Additionally, an ethanol plant, Bonanza Bioenergy was built in 2007 by Conestoga Energy Partners which uses 19.6 million bushels of grain.[26]

As of 2012, 73.9% of the population over the age of 16 was in the labor force. 0.0% was in the armed forces, and 73.9% was in the civilian labor force with 71.5% being employed and 2.4% unemployed. The composition, by occupation, of the employed civilian labor force was: 23.8% in production, transportation, and material moving; 23.5% in management, business, science, and arts; 21.9% in sales and office occupations; 19.2% in service occupations; and 11.5% in natural resources, construction, and maintenance. The industries employing the largest percentages of the working civilian labor force were educational services, health care, and social assistance (20.4%); manufacturing (19.3%); and retail trade (15.0%).[23]

The cost of living in Garden City is relatively low; compared to a U.S. average of 100, the cost of living index for the city is 81.6.[27] As of 2012, the median home value in the city was $103,400, the median selected monthly owner cost was $1,159 for housing units with a mortgage and $455 for those without, and the median gross rent was $665.[23]

Top employers

According to Garden City's 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[28] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tyson Foods | 2,200 |

| 2 | Unified School District 457 | 1,200 |

| 3 | Cheyenne Drilling | 638 |

| 4 | St. Catherine Hospital | 635 |

| 5 | Garden City Community College | 385 |

| 6 | Walmart | 372 |

| 7 | Finney County | 330 |

| 8 | City of Garden City | 303 |

| 10 | Sunflower Electric Power Corporation | 225 |

Government

Garden City is a city of the first class with a commission-manager form of government.[29] The city commission consists of five commissioners elected at-large. It meets on the first and third Tuesday of each month. The commission sets goals and policy for the city, approves the city budget, and directs the city manager. Annually, the commission selects one member to serve as mayor who then presides over commission meetings.[30] The city manager implements policies set by the commission and administers the city's operations, departments, and employees.[31]

As the county seat, Garden City is the administrative center of Finney County. The county courthouse is downtown, and all departments of the county government base their operations in the city.[32]

Garden City lies within Kansas's 1st U.S. Congressional District. For the purposes of representation in the Kansas Legislature, the city is located in the 39th district of the Kansas Senate and the 122nd and 123rd districts of the Kansas House of Representatives.[29]

Education

Colleges

Garden City Community College (GCCC) is a fully accredited community college. GCCC is a member of the Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference (KJCCC), one of the conferences in the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA).

Primary and secondary

The community is served by Garden City USD 457 public school district, which operates Garden City High School.

Infrastructure

Transportation

_in_2008.jpg.webp)

U.S. Route 50 and U.S. Route 400, both east–west highways, meet U.S. Route 83, a north–south highway, in the southeast part of the city. A U.S. 50 business route continues west from the intersection into the city. U.S. 50, U.S. 400, and U.S. 83 run concurrently around the city's eastern and northern fringe. Northwest of the city, U.S. 50 and U.S. 400 continue west while U.S. 83 turns north. South of the city, a U.S. 83 business route splits off from the main highway and enters the city as Main Street. Downtown, it intersects the U.S. 50 business route, and the two run concurrently north out of the city, terminating northwest of the city at the junction of U.S. 50 and U.S. 83. Garden City is also the western terminus of K-156 which enters the city from the northeast. Garden City was located on the National Old Trails Road, also known as the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway, that was established in 1912.

Finney County Transit operates CityLink, a public transport bus service with four routes in the city, as well as a minibus paratransit service.[33] Bus service is provided daily eastward towards Wichita by BeeLine Express (subcontractor of Greyhound Lines).[34][35]

Garden City Regional Airport is located approximately 8 miles (13 km) southeast of the city. Used primarily for general aviation, it is connected to the American Airlines network via American Eagle regional service to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport under the Essential Air Service program.

Three rail lines serve Garden City: the La Junta Subdivision of the BNSF Railway, which runs southeast–northwest, and the two lines of the Garden City Western Railway, of which the city is the southern and eastern terminus.[36] Amtrak uses the La Junta Subdivision to provide passenger rail service; Garden City is a stop on the Southwest Chief line.

Health care

Garden City is served by St. Catherine Hospital. The Southwest Kansas Surgery Center, Heart Center, Cancer Center and Maternal Child Center provide additional employment, as do several other health-related businesses.

Media

The Garden City Telegram is the local newspaper, published six days a week.[37]

Along with Dodge City, Garden City is a center of broadcast media for southwestern Kansas.[38][39] Two AM radio stations and seven FM radio stations, including one of the two flagship stations of High Plains Public Radio, broadcast from the city.[38][40]

Garden City is in the Wichita-Hutchinson, Kansas television market, and four television stations are licensed to or broadcast from the city.[41][42] These stations include NBC, ABC, and FOX network affiliates, all of which are satellite stations of their respective affiliates in Wichita.[39][43] The fourth station, KGCE-LD, is a sister station of KDGL-LD in Sublette, Kansas.[44][45]

Culture

Arts and music

Garden City Arts is a non-profit organization dedicated to enriching lives and encouraging creativity through the arts. Its gallery offers 10 to 12 exhibits per year along with internships and educational programming.[46]

In recent years, an annual music festival called the Hillside Sessions[47] has taken place at an historic structure which over the decades has been a barn, an industrial atelier and a dance hall.

An annual music festival called the Tumbleweed Festival is held over a weekend in late August every year at Lee Richardson Zoo. Usually performers are a mix of local talent and acts brought in by the festival board.

Points of interest

Initially named by its developers "The Big Dipper", Garden City's "The Big Pool" is larger than a 100-yard football field, holds 2.2 million gallons of water and is large enough to accommodate water-skiing. Originally hand-dug in 1922, a bathhouse was added by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression, and local farmers used horse-drawn soil-scrapers to later enlarge the pool. The pool hosts 50-meter Olympic swimming lanes, three water slides, and a children's pool with zero-entry depth. The pool employs a minimum of 14 lifeguards, two slide assistants, three admission clerks, two concession workers and a pool manager on duty each day. Advertised for years as "The World's Largest, Free, Outdoor, Municipal, Concrete Swimming Pool", the pool has been known to count up to 2,000 patrons during the summer months. In order to finance improvements made in recent years, an admission fee is now charged. In 2020 the Big Pool was renovated and re-branded as Garden City Rapids. Several large water slides and a lazy river were added.

Located inside 110-acre (0.45 km2) Finnup Park, the pool is co-located with Finney County Historical Museum and Lee Richardson Zoo, the largest zoological facility in western Kansas, housing more than 300 animals representing 110 species. Walking tours are free to the public; there is a charge for driving into the zoo.

A few miles from Finnup Park, the Big Pool and Lee Richardson Zoo is the Buffalo Game Preserve, with one of the largest herds of bison in the world.[48]

_from_NE_1.JPG.webp)

The Windsor Hotel, built downtown in 1887 by John A. Stevens, was known as the "Waldorf of the Prairies" because of its lavish quarters. Among its early guests were Eddie Foy, Lillian Russell, Jay Gould and Buffalo Bill Cody, who stayed in the presidential suite on the third floor. The Windsor, which closed in 1977, is owned by the Finney County Preservation Alliance. The hotel is four stories high, or about 50 ft (15 m) tall.[49] The Finney County Preservation Alliance is working with New Communities LLC of Denver, Colorado to renovate the hotel into a 65-room boutique hotel with restaurant and bar on the ground floor.[50][51]

In popular culture and the arts

Garden City is depicted in Truman Capote's In Cold Blood.

Billie Jo Spears' 1969 Billboard country hit song "Mr. Walker, It's All Over" is about a young woman from Garden City who moves to New York City to become a big-city secretary and quickly becomes disenchanted.

Sports

Garden City is home to the Garden City Wind baseball team, which plays in the Pecos League.

Garden City is also home to the Garden City High School Buffaloes. The school offers football, basketball, soccer, wrestling, track and field, baseball, softball, tennis, and swimming. Garden City is a part of the 6A level of sports in the state of Kansas. The Buffaloes have had success in wrestling, winning state titles in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. The school has had success in football as well, winning the state championship in 1999.

The football team at Garden City Community College won the NJCAA National Championship in 2016. The college sponsors teams in 14 sports. The teams are known as the Broncbusters, often shortened to the Busters. The colors are seal brown and gold.

Notable people

Notable individuals who were born in or have lived in Garden City include novelist Sanora Babb,[52] jazz pianist Frank Mantooth,[53] former Governor of Colorado Roy Romer,[54] professional football players Thurman "Fum" McGraw and Hal Patterson and successful professional boxers Victor Ortiz, Antonio Orozco, and Brandon Rios.[55][56]

Sister cities

Garden City has two sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Ciudad Quesada, Costa Rica

Ciudad Quesada, Costa Rica Oristano, Sardinia, Italy

Oristano, Sardinia, Italy

Gallery

Downtown Garden City

Downtown Garden City The Finney County Public Library in Garden City

The Finney County Public Library in Garden City Defunct State Theatre in downtown Garden City

Defunct State Theatre in downtown Garden City Community Congregational Church in Garden City

Community Congregational Church in Garden City St. Thomas' Episcopal Church in Garden City

St. Thomas' Episcopal Church in Garden City The former Pleasant Valley School has been relocated to Finnup Park in Garden City.

The former Pleasant Valley School has been relocated to Finnup Park in Garden City. The Garden City Western Railway Company train on display in Finnup Park

The Garden City Western Railway Company train on display in Finnup Park

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Finney County, Kansas

- Santa Fe Trail

- National Old Trails Road

References

![]() This article incorporates text from Conquest of Southwest Kansas, by Leola Howard Blanchard, a publication from 1931, now in the public domain in the United States.[57][58][59]

This article incorporates text from Conquest of Southwest Kansas, by Leola Howard Blanchard, a publication from 1931, now in the public domain in the United States.[57][58][59]

- Beef Empire Days

- "Garden City, Kansas", Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Profile of Garden City, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- "QuickFacts; Garden City, Kansas; Population, Census, 2020 & 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- "Garden City History" (English). Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- Exhibit, Finney County Historical Museum, Garden City, Kansas

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau.

- Frank Morris (February 19, 2017). "A Thriving Rural Town's Winning Formula Faces New Threats Under Trump Administration [transcript]". Weekend Edition. National Public Radio. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Pressler, Jessica (12 December 2017). "A Militia's Plot to Bomb Somali Refugees in a Kansas Town". New York Magazine. Retrieved 2017-12-31.

- Ellis, Ralph (October 16, 2016). "Attack on Somalis in Kansas thwarted, feds say". CNN. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Potter, Tim; Leiker, Amy Renee (October 14, 2016). "Terrorist plot by militia group in Kansas thwarted". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Shorman, Jonathan (October 14, 2016). "Alleged Garden City bombing plot revealed". The Garden City Telegram. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Hegeman, Roxana (25 January 2019). "Militia Members Get Decades in Prison in Kansas Bomb Plot". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 2019-04-21.

- "2003-2004 Official Transportation Map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. 2003. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "City Distance Tool". Geobytes. Archived from the original on 2010-10-05. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007-03-01). "Updated Köppen-Geiger climate classification map" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions (4): 439–473. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- "Average Weather for Garden City, KS". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- "Historical Weather for Garden City, Kansas, United States of America". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service Forecast Office - Dodge City, KS. Retrieved 2014-01-17.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680-1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. p. 1091. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- Morris, Frank (2017-02-19). "A Thriving Rural Town's Winning Formula Faces New Threats Under Trump Administration". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- Benson, Janet E. (Kansas State University). "Garden City: Meatpacking and Immigration to the High Plains -- Dr. Janet E. Benson." University of California, Davis. Retrieved on February 25, 2017.

- "Kansas Ethanol". Archived from the original (English) on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- "Garden City, Kansas". City-Data.com. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- City of Garden City CAFR Archived 2015-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Garden City". Directory of Kansas Public Officials. The League of Kansas Municipalities. Archived from the original on 2014-08-15. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "City Commission". City of Garden City, Kansas. Archived from the original on 2014-08-31. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "City Manager". City of Garden City, Kansas. Archived from the original on 2014-08-30. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "Departments". Finney County, Kansas. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "Transportation". Senior Center of Finney County. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- info@beeline-express.com, beeline-express. "Beeline Express". www.beeline-express.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Home". www.greyhound.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Kansas Operating Division" (PDF). BNSF Railway. 2009-01-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-25. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- "Garden City Telegram". Mondo Times. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "Radio Stations in Garden City, Kansas". Radio-Locator. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "Stations for Garden City, Kansas". RabbitEars.Info. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "Visit HPPR's Studios". High Plains Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "TV Market Maps". EchoStar Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "TVQ TV Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "KSAS Coverage Map" (PDF). KSAS-TV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- "TV23 KDGL-TV - Coverage". Archived from the original on 2013-08-11. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- "TV Query Broadcast Station Search". fcc.gov. 10 December 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Garden City Arts". Facebook.

- "Hilliside Sessions". Garden City Telegram. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- "Garden City, KS - World's Largest Outdoor Municipal Concrete Swimming Pool". RoadsideAmerica.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Windsor Hotel". gardencitychamber.net. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- "Windsor Hotel, Garden City". Kansas Sampler Foundation. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Developers propose new plan for Windsor Hotel". Garden City Telegram. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Biography: Sanora Babb". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "Frank Mantooth, 56; Albums Earned 11 Grammy Nominations". Los Angeles Times. 2004-02-02. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "Biography of Governor Roy Romer". Colorado State Archives. 1997-05-05. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "Thurman McGraw". National Football League. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- "Hall Patterson". Canadian Football League. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ""Conquest of Southwest Kansas" - this user's library - Google Books". books.google.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; Complaints, California 94305 Copyright. "Copyright Renewals". Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)