George Eastman

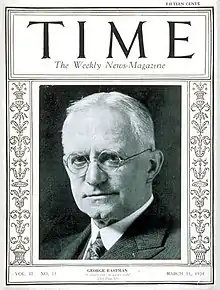

George Eastman (July 12, 1854 – March 14, 1932) was an American entrepreneur who founded the Eastman Kodak Company and helped to bring the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream. He was a major philanthropist, establishing the Eastman School of Music, Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, and schools of dentistry and medicine at the University of Rochester and in London Eastman Dental Hospital; contributing to the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) and the construction of several buildings at the second campus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on the Charles River. In addition, he made major donations to Tuskegee University and Hampton University, historically black universities in the South. With interests in improving health, he provided funds for clinics in London and other European cities to serve low-income residents.

George Eastman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 12, 1854 Waterville, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 14, 1932 (aged 77) Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Ashes buried at Eastman Business Park (Kodak Park) |

| Occupation | Businessman, inventor, philanthropist |

| Known for |

|

| Signature | |

| |

In his final two years, Eastman was in intense pain caused by a disorder affecting his spine. On March 14, 1932, Eastman shot himself in the heart, leaving a note which read, "To my friends: my work is done. Why wait?"[1]

The George Eastman Museum has been designated a National Historic Landmark. Eastman is the only person represented by two stars both in the Film category in the Hollywood Walk of Fame, one on the north side of the 6800 block of Hollywood Boulevard and the other one on the west side of the 1700 block of Vine Street, recognizing the same achievement, that he developed bromide paper, which became a standard of the film industry.[2][3]

Early life

Eastman was born in Waterville, New York,[4] as the youngest child of George Washington Eastman and Maria Eastman (née Kilbourn), at the 10-acre (4.0 ha) farm which his parents had bought in 1849. He had two older sisters, Ellen Maria and Katie.[5] He was largely self-educated, although he attended a private school in Rochester after the age of eight.[5] In the early 1840s his father had started a business school, the Eastman Commercial College in Rochester, New York. The city became one of the first "boomtowns" in the United States, based on rapid industrialization.[5] As his father's health started deteriorating, the family gave up the farm and moved to Rochester in 1860.[5] His father died of a brain disorder on April 27, 1862. To survive and afford George's schooling, his mother took in boarders.[5]

The second daughter, Katie, had contracted polio when young and died in late 1870 when George was 15 years old. The young George left school early and started working to help support the family. As Eastman began to have success with his photography business, he vowed to repay his mother for the hardships she had endured in raising him.[6]

Career

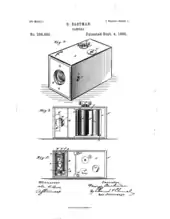

In 1884, Eastman patented the first film in roll form to prove practicable; he had been tinkering at home to develop it. In 1888, he developed the Kodak camera ("Kodak" being a word Eastman created), which was the first camera designed to use roll film he had invented.

Eastman sold the camera loaded with enough roll film for 100 exposures. When all the exposures had been made, the photographer mailed the camera back to Kodak in Rochester, along with $10. The company would process the film, make a print of each exposure, load another roll of film into the camera, and send the camera and the prints to the photographer. Eastman coined the advertising slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest,” which quickly became popular among customers. At first, no other company could process the film or sell the unexposed film.[7] In 1889 he first offered film stock, and by 1896 became the leading supplier of film stock internationally.[8] He incorporated his company under the name Eastman Kodak, in 1892.[9] As film stock became standardized, Eastman continued to lead in innovations. Refinements in colored film stock continued after his death.

In an era of growing trade union activities, Eastman sought to counter the union movement by devising worker benefit programs, including, in 1910, the establishment of a profit-sharing program for all employees.[9] Considered to be a progressive leader for the times, Eastman promoted Florence McAnaney to be head of the personnel department. She was one of the first women to hold an executive position in a major U.S. company.

Personal life

George Eastman never married. He was close to his mother and to his sister and her family. He had a long platonic relationship with Josephine Dickman, a trained singer and the wife of business associate George Dickman, becoming especially close to her after the death of his mother, Maria Eastman, in 1907. He was also an avid traveler and had a passion for playing the piano.[5]

The loss of his mother, Maria, was particularly crushing to George. Almost pathologically concerned with decorum, he found himself, for the first time, unable to control his emotions in the presence of his friends. "When my mother died I cried all day", he explained later. "I could not have stopped to save my life." Due to his mother's reluctance to accept his gifts, George Eastman could never do enough for his mother during her lifetime. He continued to honor her after her death. On September 4, 1922, he opened the Eastman Theatre in Rochester, which included a chamber-music hall, Kilbourn Theater, dedicated to his mother's memory. At the Eastman House he maintained a rose bush, using a cutting from her childhood home.[6]

Later years

Eastman was a presidential elector in 1900[10] and 1916.[11]

Eastman was associated with the Kodak company in an administrative and a business executive capacity until his death; he contributed much to the development of its notable research facilities. In 1911 he founded the Eastman Trust and Savings Bank.

In the 1920s, he was involved in calendar reform and supported the 13-month per year International Fixed Calendar developed by Moses B. Cotsworth.[12] He wrote several articles including, "Problems of Calendar Improvement", in Scientific American (June 1931, pp. 382–385)[13][14] and "The Importance of Calendar Reform to the Business World", in Nation's Business (May 1926, pp. 42–46). By 1928, the Kodak Company implemented the calendar in its business bookkeeping, and continued to use it until 1989. He was chairman of the National Committee on Calendar Simplification and his calendar was one of two finalists out of over 150 to be presented to the League of Nations.[15] With his death and the looming tensions of WWII, it was dropped from consideration.[16][17]

He was one of the outstanding philanthropists of his era, donating more than $100 million to various projects in Rochester; in Cambridge, Massachusetts; at two historically black colleges in the South and in several European cities.[18] (Figured for its value in 1932, the year of Eastman's death, $100 million is equivalent to more than $2 billion in 2022.)[19]

In 1918, he endowed the establishment of the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester, and in 1921 a school of medicine and dentistry there. In 1922, he founded the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, hiring its first music director Albert Coates.[20]

In 1925 Eastman gave up his daily management of Kodak to become treasurer. He concentrated on philanthropic activities, to which he had already donated substantial sums. For example, he donated funds to establish the Eastman Dental Dispensary in 1916. He ranked slightly behind Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and a few others in his philanthropy, but did not seek publicity for his activities. He concentrated on institution-building and causes that could help people's health. From 1925 until his death, Eastman also donated $10,000 per year to the American Eugenics Society (increasing the donation to $15,000 in 1932), a popular cause among many of the upper class when there were concerns about immigration and "race mixing".[21]

Eastman donated £200,000 in 1926 to fund a dental clinic in London after being approached by the chairman of the Royal Free Hospital, George Riddell, 1st Baron Riddell. Donations of £50,000 each had been made by Lord Riddell and the Royal Free honorary treasurer. On November 20, 1931, the UCL Eastman Dental Institute opened in a ceremony attended by Neville Chamberlain, then Minister of Health, and the American Ambassador to the UK. The clinic was incorporated into the Royal Free Hospital and was committed to providing dental care for disadvantaged children from central London. It is now a part of University College London.[22] In 1929 he founded the George Eastman Visiting Professorship at Oxford, to be held each year by a different American scholar of the highest distinction.

Eastman also funded Eastmaninstitutet, a dental care clinic for children opened in 1937 in Stockholm, Sweden.

Infirmity and suicide

In his final two years, Eastman was in intense pain caused by a disorder affecting his spine. He had trouble standing, and his walk became a slow shuffle. Today, it might be diagnosed as a form of degenerative disease such as disc herniations from trauma or age causing either painful nerve root compressions, or perhaps a type of lumbar spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal caused by calcification in the vertebrae. Since his mother suffered the final two years of her life in a wheelchair,[6] she also may have had a spine condition but that is uncertain. Only her uterine cancer and successful surgery are documented in her health history.[5]

Eastman suffered from depression due to his pain, reduced ability to function, and also since he had witnessed his mother's suffering from pain. On March 14, 1932, Eastman died by suicide with a single gunshot through the heart. His suicide note read, "To my friends, my work is done – Why wait? GE."[1]

Raymond Granger, an insurance salesman in Rochester, was visiting to collect insurance payments from several members of the staff. He arrived at the scene to find the workforce in a dither. At least one chronicler said that fear of senility or other debilitating diseases of old age was a contributing factor.[23]

Eastman's funeral was held at St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Rochester; his coffin was carried out to Charles Gounod's "Marche Romaine" and buried in the grounds of the company he founded, at what is now known as Eastman Business Park.[24]

Legacy

Being an astute business man, Eastman focused his company on making film when competition heated up in the camera industry. By providing quality and affordable film to every camera manufacturer, Kodak managed to turn its competitors into de facto business partners.[25]

In 1915, Eastman founded a bureau of municipal research in Rochester "to get things done for the community" and to serve as an "independent, non-partisan agency for keeping citizens informed". Called the Center for Governmental Research, the agency continues to carry out that mission.[26]

During his lifetime, Eastman donated $100 million to various organizations, with most of his money going to the University of Rochester and to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to build their programs and facilities (under the alias "Mr. Smith"). He was one of the major philanthropists in the United States during his lifetime.[27][18] The Rochester Institute of Technology has a building dedicated to Eastman, in recognition of his support and substantial donations. MIT installed a plaque of Eastman on one of the buildings he funded. (Students rub the nose of Eastman's image on the plaque for good luck.) Eastman also made substantial gifts to the Tuskegee Institute and the Hampton Institute in Alabama and Virginia, respectively.[28]

Security Trust Company of Rochester was the executor of Eastman's estate.[29] His entire estate was bequeathed to the University of Rochester.[30] The Eastman Quadrangle of the River Campus of the University of Rochester was named for him.[31]

Eastman had built a mansion at 900 East Avenue in Rochester. Here he entertained friends to dinner and held private music concerts. The University of Rochester used the mansion for various purposes for decades after his death. In 1949, it re-opened after having been adapted for use as the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film. It has been designated a National Historic Landmark,[32] and is now known as the George Eastman Museum.

Eastman's boyhood home was saved from destruction. It was restored to its state during his childhood and is displayed at the Genesee Country Village and Museum.[33]

Patents

- U.S. Patent 226,503 "Method and Apparatus for Coating Plates", filed September 1879, issued April 1880.

- U.S. Patent 306,470 "Photographic Film", filed May 10, 1884, issued October 14, 1884.

- U.S. Patent 306,594 "Photographic Film", filed March 7, 1884, issued October 14, 1884.

- U.S. Patent 317,049 (with William H. Walker) "Roll Holder for Photographic Films", filed August 1884, issued May 1885.

- U.S. Patent 388,850 "Camera", filed March 1888, issued September 1888.

- Eastman licensed, then purchased U.S. Patent 248,179 "Photographic Apparatus" (roll film holder), filed June 21, 1881, issued October 11, 1881, to David H. Houston.

Honors and commemorations

- In 1930 he was awarded the American Institute of Chemists Gold Medal.

- In 1934, the George Eastman Monument at Kodak Park (now Eastman Business Park) was unveiled.[34]

- On July 12, 1954, the U.S. Post Office issued a three-cent commemorative stamp marking the 100th anniversary of George Eastman's birth, which was first issued in Rochester, New York.[35]

- Also in 1954, to commemorate Eastman's 100th birthday, the University of Rochester erected a meridian marker near the center of Eastman Quadrangle on the campus of the University of Rochester using a gift from Eastman's former associate and University alumnus Charles F. Hutchison.[36]

- In the fall of 2009, a statue of Eastman was erected approximately 60 feet (18 m) north by northeast of the meridian marker on the Eastman Quadrangle of the University of Rochester.

- In 1966, the George Eastman House was designated a National Historic Landmark.

- The auditorium at the Dave C. Swalm School of Chemical Engineering at Mississippi State University is named for Eastman, in recognition of his inspiration to Swalm.

- In 1968 George Eastman was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.[37]

George Eastman commemorative issue, 1954 |

|

A first day cover honoring George Eastman 1954 |

Meridian marker and Eastman memorial |

Other

An often repeated urban legend recounts that photographer and musician Linda McCartney (née Eastman, first wife of Beatle Sir Paul McCartney) was related to the George Eastman family, but this is false. Her father was of Russian Jewish ancestry and changed his surname to Eastman before becoming known as an attorney.[38]

At least one biographical film has been made about George Eastman. It was an independent production made in the 1940s, apparently never preserved and mostly lost to time, titled either The Life of George Eastman or George Eastman: Some Scenes From His Life. The film, aired on television for a time into the 1960s, ends with his development of the all-color negative film. In 1981, the short film The Lengthened Shadow of a Man about Eastman was made, the title of which comes from the T. S. Eliot poem 3. Sweeney Erect.[39]

See also

- Stanley Motor Carriage Company

References

- Peers, Juliette (2016), "The Lindsay Family (1870–1958)", Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism, London: Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781135000356-rem1589-1, ISBN 978-1-135-00035-6, archived from the original on November 6, 2021, retrieved January 20, 2021

- "Hollywood Walk of Fame – George Eastman, cited on April 5, 2021". October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- "Hollywood Star Walk – George Eastman". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- McNellis, David (2010). Reflections on Big Spring: A History of Pittsford, NY, and the Genesee River Valley. AuthorHouse. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4520-4358-6. OCLC 1124409654. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Brayer, Elizabeth (1996). George Eastman: A Biography. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5263-3. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2016. (University of Rochester Press, 2006 reprint: ISBN 1-580-46247-2. pp. 12–19)

- Lindsay, David. "Key Figures in Eastman's Life". American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- Smith, Fred R. "You press the button...we do the rest". Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Kodak Film History | Chronology of Motion Picture Films – 1889 to 1939" (PDF). aipcinema.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike; George Alike, George Alike (January 21, 2011). "MyFavoritegamez.com – Free Online Games For Kids". SciVee. doi:10.4016/26742.01. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Electors to Cast Vote". New-York Tribune. Vol. LX, no. 19783. New York. January 14, 1901. p. 1 – via Chronicling America.

- "Electors Forget the Law". The New York Times. November 27, 1916.

- "University of Rochester Library Bulletin: George Eastman, A Bibliographical Essay of Selected References | RBSCP". Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- "Problems of Calendar Improvement - Scientific American". Scientific American. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- Eastman, George (1931). "Problems of Calendar Improvement". Scientific American. 144 (6): 382–385. Bibcode:1931SciAm.144..382E. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0631-382. JSTOR 24975703. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "The case for an entirely new calendar". Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- "The Death and Life of the 13-Month Calendar". Bloomberg News. December 11, 2014. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- Ford, Carin T. (2004). George Eastman: The Kodak Camera Man. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishing. ISBN 0-7660-2247-1. OCLC 52091133.

- "$100,000 in 1932 is Worth $2,133,047.45 Today", https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1932?amount=100000

- "Eastman Engages Conductor Coates; Famous British Musician to Direct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra. His First Concert Jan. 16 Guest Conductor of Symphony Society, Who Made a Deep Impression Here, Sails for London Today". The New York Times. June 12, 1923. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Spiro, Jonathan (2009). Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant. UPNE. pp. 182, 353. ISBN 978-1-58465-810-8. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Black, Nick (2006). Walking London's Medical History. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press. ISBN 978-1-85315-619-9. OCLC 76817853. Archived from the original on March 27, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Sandburg, Carl (1990) [1936]. "Chapter 7". The people, yes (First Harvest ed.). Boston: Harcourt, Brace and Company. ISBN 978-0-544-41692-5. OCLC 900606927. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- Quigley, Kathleen (March 18, 1990). "Splendor Restored At Eastman House". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- Heineman, Ted (2009). "George Eastman". Riverside Cemetery Journal. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "About CGR". Center for Governmental Research. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- Zinsmeister, Karl. "George Eastman". Philanthropy Roundtable. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- Ackerman, Carl W. (2000) [1930]. George Eastman : Founder of Kodak and the photography business. Washington, D.C.: BeardBooks. p. 466. ISBN 1-893122-99-9. OCLC 58845378.

- Morrell, Alan (January 7, 2017). "Whatever Happened To ... Security Trust?". Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- "After 40 years, two collections of George Eastman's papers reunite at the George Eastman Museum". George Eastman Museum. January 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "University of Rochester: Campuses and Landmarks". University of Rochester. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- "National Register Information System – George Eastman House (#66000529)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Genesee Country Village and Museum". Genesee Country Village. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- "Eastman monument a reminder of what was, what could be". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. April 2, 2014. p. 1B. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "George Eastman Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. 1954. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- "Hutchison (Charles F.) Collection". rbscp.lib.rochester.edu. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "George Eastman". International Photography Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- Skanse, Richard (April 20, 1998). "Linda McCartney Dies at 56". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- Eliot, T. S. (1920). "3. Sweeney Erect". www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

Further reading

- Ackerman, Carl W. (1930). George Eastman: Founder of Kodak and the Photography Business. Beard Books. ISBN 1-893-12299-9.

- Brayer, Elizabeth (1996). George Eastman: A Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801852633.

External links

- George Eastman archive at the University of Rochester

- George Eastman House Archived December 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- George Eastman: His Life, Legacy, and Estate, George Eastman House

- UCL Eastman Dental Institute, London

- Eastman Institute for Oral Health, University of Rochester, NY

- Newspaper clippings about George Eastman in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW