Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot[lower-alpha 1] (August 11, 1865 – October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsylvania. He was a member of the Republican Party for most of his life, though he joined the Progressive Party for a brief period.

Gifford Pinchot | |

|---|---|

Gifford Pinchot portrait by Pirie MacDonald, 1909 | |

| 28th Governor of Pennsylvania | |

| In office January 20, 1931 – January 15, 1935 | |

| Lieutenant | Edward Shannon |

| Preceded by | John Stuchell Fisher |

| Succeeded by | George Earle |

| In office January 16, 1923 – January 18, 1927 | |

| Lieutenant | David J. Davis |

| Preceded by | William Sproul |

| Succeeded by | John Stuchell Fisher |

| 1st Chief of the United States Forest Service | |

| In office February 1, 1905 – January 7, 1910 | |

| President | Theodore Roosevelt William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | Office Created |

| Succeeded by | Henry Graves[a] |

| 4th Chief of the Division of Forestry | |

| In office March 15, 1898 – February 1, 1905 | |

| President | William McKinley Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Bernhard Fernow |

| Succeeded by | Himself[b] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 11, 1865 Simsbury, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | October 4, 1946 (aged 81) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Other political affiliations | Progressive "Bull Moose" (1912) |

| Spouse | Cornelia Bryce Pinchot |

| Alma mater | Yale University |

| Signature | |

| a.^ Albert F. Potter served as acting chief of the Forest Service until Graves was selected for appointment to the position on a permanent basis.[1][2] b.^ As Chief of the Forest Service. | |

Born into the wealthy Pinchot family, Gifford Pinchot embarked on a career in forestry after graduating from Yale University in 1889. President William McKinley appointed Pinchot as the head of the Division of Forestry in 1898, and Pinchot became the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service after it was established in 1905. Pinchot enjoyed a close relationship with President Theodore Roosevelt, who shared Pinchot's views regarding the importance of conservation. After William Howard Taft succeeded Roosevelt as president, Pinchot was at the center of the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy, a dispute with Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger that led to Pinchot's dismissal. The controversy contributed to the split of the Republican Party and the formation of the Progressive Party prior to the 1912 presidential election. Pinchot supported Roosevelt's Progressive candidacy, but Roosevelt was defeated by Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Pinchot returned to public office in 1920, becoming the head of the Pennsylvania's forestry division under Governor William Cameron Sproul. He succeeded Sproul by winning the 1922 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election. He won a second term as governor through a victory in the 1930 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, and supported many of the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, Pinchot led the establishment of the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board, calling it "the best liquor control system in America".[4] He retired from public life after his defeat in the 1938 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, but remained active in the conservation movement until his death in 1946.

Early life and education, 1865 through 1890

Gifford Pinchot was born in Simsbury, Connecticut on August 11, 1865.[5] He was named for Hudson River School artist Sanford Robinson Gifford.[6] Pinchot was the oldest child of James W. Pinchot, a successful New York City interior furnishings merchant, and Mary Eno, daughter of one of New York City's wealthiest real estate developers, Amos Eno.[7] James and Mary were both well-connected with prominent Republican Party leaders and former Union generals, including family friend William T. Sherman, and they would frequently aid Pinchot's later political career.[8] Pinchot's paternal grandfather had migrated from France to the United States in 1816, becoming a merchant and major landowner based in Milford, Pennsylvania.[9] His mother's maternal grandfather, Elisha Phelps, and her uncle, John S. Phelps, both served in Congress.[10] Pinchot had one younger brother, Amos, and one younger sister, Antoinette, who later married British diplomat Alan Johnstone.[11]

Pinchot was educated at home until 1881, when he enrolled in Phillips Exeter Academy.[12] James made conservation a family affair and suggested that Gifford should become a forester, asking him just before he left for Yale in 1885, "How would you like to become a forester?"[13] At Yale, Pinchot became a member of the Skull and Bones society, played on the football team under coach Walter Camp, and volunteered with the YMCA.[14] With the encouragement of his parents Pinchot continued to pursue the nascent field of forestry after graduating from Yale in 1889.[15] He traveled to Europe, where he met with leading European foresters such as Dietrich Brandis and Wilhelm Philipp Daniel Schlich, who suggested that Pinchot study the French forestry system.[16] Brandis and Schlich had a strong influence on Pinchot, who would later rely heavily upon Brandis' advice in introducing professional forest management in the U.S.[17] Pinchot studied at the French National School of Forestry in Nancy.[18] This is where his formal studies took place, and where he learned the basics of forest economics, law, and science. It was also where he first encountered a professionally managed forest, where, "[The French Forests] were divided at regular intervals by perfectly straight paths and roads at right angle to each other, and they were protected to a degree we in America know nothing about." Pinchot returned to America after thirteen months before completing his curriculum and against the advise of his professors. Pinchot felt that additional training was unnecessary and what mattered was getting the profession of forestry started in America.[19]

Early career, 1890–1910

Early roles

Pinchot landed his first professional forestry position in early 1892, when he became the manager of the forests at George Washington Vanderbilt II's Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina.[20] The following year, Pinchot met John Muir, a naturalist who founded the Sierra Club and would become Pinchot's mentor and, later, his rival.[21] Pinchot worked at Biltmore until 1895, when he opened a consulting office in New York City.[22] In 1896, he embarked on a tour of the American West with the National Forest Commission.[23] Pinchot disagreed with the commission's final report, which advocated preventing U.S. forest reserves from being used for any commercial purpose; Pinchot instead favored the development of a professional forestry service which would preside over limited commercial activities in forest reserves.[24] In 1897, Pinchot became a special forest agent for the United States Department of the Interior.[25]

Head of the Division of Forestry

In 1898, Pinchot became the head of the Division of Forestry, which was part of the United States Department of Agriculture.[26] Pinchot is known for reforming the management and development of forests in the United States and for advocating the conservation of the nation's reserves by planned use and renewal.[27] His approach set him apart from some other leading forestry experts, especially Bernhard E. Fernow and Carl A. Schenck. In contrast to Pinchot's national vision, Fernow advocated a regional approach, while Schenck favored private enterprise effort.[28] Pinchot's main contribution was his leadership in promoting scientific forestry and emphasizing the controlled, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so they would be of maximum benefit to mankind. He coined the term conservation ethic as applied to natural resources.[27] Under his leadership, the number of individuals employed by the Division of Forestry grew from 60 in 1898 to 500 in 1905; he also hired numerous part-time employees who worked only during the summer.[29] The Division of Forestry did not have direct control over the national forest reserves, which were instead assigned to the U.S. Department of Interior, but Pinchot reached an arrangement with the Department of Interior and state agencies to work on reserves.[30]

In 1900, Pinchot established the Society of American Foresters, an organization that helped bring credibility to the new profession of forestry, and was part of the broader professionalization movement underway in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. Pursuant to the goal of professionalization, the Pinchot family endowed a 2-year graduate-level School of Forestry at Yale University, which is now known as the Forest School at the Yale School of the Environment.[31] It became the third school in the U.S. that trained professional foresters, after the New York State College of Forestry at Cornell and the Biltmore Forest School.[32] Central to his publicity work was his creation of news for magazines and newspapers.[33]

Chief of the United States Forest Service

Pinchot's friend, Theodore Roosevelt, became president in 1901, and Pinchot became part of the latter's informal "Tennis Cabinet". Pinchot and Roosevelt shared the view that the federal government must act to regulate public lands and provide for the scientific management of public resources.[34] In 1905, Roosevelt and Pinchot convinced Congress to establish the United States Forest Service, an agency charged with overseeing the country's forest reserves.[35] As the first head of the Forest Service, Pinchot implemented a decentralized structure that empowered local civil servants to make decisions about conservation and forestry.[36]

Pinchot's conservation philosophy was influenced by ethnologist William John McGee and utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham,[37] as well as the ethos of the Progressive Era. Like many other Progressive Era reformers, Pinchot emphasized that his field was important primarily for its social utility and could be best understood through scientific methods.[38] He was generally opposed to preservation for the sake of wilderness or scenery, a fact perhaps best illustrated by the important support he offered to the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park.[39] Pinchot used the rhetoric of the market economy to disarm critics of efforts to expand the role of government: scientific management of forests and natural resources was profitable. While most of his battles were with timber companies that he thought had too narrow a time horizon, he also battled the forest preservationists like John Muir, who were deeply opposed to commercializing nature.[40] Pinchot's policies also aroused opposition from ranchers, who opposed regulation of livestock grazing in public lands.[41][lower-alpha 2]

The Roosevelt administration's efforts to regulate public land led to blowback in Congress, which moved to combat "Pinchotism" and reassert control over the Forest Service.[43] In 1907, Congress passed an act prohibiting the president from creating more forest reserves. With Pinchot's help, President Roosevelt responded by creating 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of new National Forests (which became known as "midnight forests") just minutes before he lost the legal power to do so.[44] Despite congressional opposition, Roosevelt, Pinchot, and Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield continued to find ways to protect public land from private development during Roosevelt's last two years in office.[45]

Pinchot–Ballinger controversy

Pinchot continued to lead the Forest Service after Republican William Howard Taft succeeded Roosevelt in 1909, but did not retain the level of influence he had held under Roosevelt.[46] Taft mistrusted Pinchot and did not have patience for Pinchot operating with more authority than what Taft thought was appropriate. Taft once stated, "Pinchot is a socialist and a spiritualist, a strange combination and one that is capable of any extreme act."[47] After taking office, Taft replaced Secretary of the Interior James Rudolph Garfield with Richard Ballinger.[48] When Ballinger approved of long-disputed mining claims to coal deposits in Alaska in 1909, Land Office agent Louis Glavis broke governmental protocol by going outside the Interior Department to seek help from Pinchot.[49] Concerned about the possibility of fraud in the claim, and skeptical of Ballinger's commitment to conservation, Pinchot intervened in the dispute on behalf of Glavis. In the midst of a budding controversy, Taft came down in favor of Ballinger, who was authorized to dismiss Glavis.[50] Though Taft hoped to avoid further controversy, Pinchot became determined to dramatize the issue by forcing his own dismissal.[51] After Pinchot publicly criticized Ballinger for several months, Taft dismissed Pinchot in January 1910.[52] Pinchot maneuvered behind the scenes to ensure the appointment of his ally, Henry S. Graves, as the new head of the Forest Service.[53]

Fire Storm of 1910 and the Descent of the Forest Service

Pinchot hand-picked William Greeley, the son of a Congregational minister, who finished at the top of that first Yale forestry graduating class of 1904, to be the Forest Service's Region 1 forester, with responsibility over 41 million acres (170,000 km2) in 22 National Forests in four western states (all of Montana, much of Idaho, Washington, and a corner of South Dakota).[3]

One year after the Great Fire of 1910, the religious Greeley succeeded in receiving a promotion to a high administration job in Washington. In 1920, he became Chief of the Forest Service. The fire of 1910 convinced him that Satan was at work, the fire converted him into a fire extinguishing partisan who elevated firefighting to the raison d'être — the overriding mission — of the Forest Service.[3] Under Greeley, the Service became the fire engine company, protecting trees so the timber industry could cut them down later at government expense. Pinchot was appalled. The timber industry successfully oriented the Forestry Service toward policies favorable to large-scale harvesting via regulatory capture, and metaphorically, the timber industry was now the fox in the chicken coop.[25] Pinchot and Roosevelt had envisioned, at the least, that public timber should be sold only to small, family-run logging outfits, not to big syndicates. Pinchot had always preached of a "working forest" for working people and small-scale logging at the edge, preservation at the core. In 1928 Bill Greeley left the Forest Service for a position in the timber industry, becoming an executive with the West Coast Lumberman's Association.[26]

When Pinchot traveled west in 1937, to view those forests with Henry S. Graves, what they saw "tore his heart out". Greeley's legacy, combining modern chain saws and government-built forest roads, had allowed industrial-scale clear-cuts to become the norm in the western national forests of Montana and Oregon. Entire mountainsides, mountain after mountain, were treeless. "So this is what saving the trees was all about." "Absolute devastation", Pinchot wrote in his diary. "The Forest Service should absolutely declare against clear-cutting in Washington and Oregon as a defensive measure", Pinchot wrote.[27]

Later career, 1910–1935

Progressive Party

At Roosevelt's request, Pinchot met Roosevelt in Europe in 1910, where they discussed Pinchot's dismissal by Taft.[54] Roosevelt subsequently expressed disappointment with Taft's policies and began to publicly distance himself from Taft.[55] Along with Amos Pinchot and several other individuals, Pinchot helped establish the Progressive Party, which nominated Roosevelt for president in the 1912 United States presidential election. The Pinchots represented the more ideologically left wing faction of the party, and they frequently feuded with financier George Walbridge Perkins.[56] Though Pinchot campaigned extensively for Roosevelt, Roosevelt and Taft were both defeated by Democrat Woodrow Wilson.[57]

Pinchot continued to affiliate with the Progressives after the 1912 election, working to build the party in Pennsylvania.[58] He ran as the Progressive nominee in the 1914 U.S. Senate election, but was defeated by incumbent Republican Senator Boies Penrose.[59] The Progressive Party collapsed after Roosevelt refused to run in the 1916 presidential election, and Pinchot subsequently re-joined the Republican Party.[60] He supported Republican Warren G. Harding's successful campaign in the 1920 presidential election, but, despite some speculation that he would be appointed as Secretary of Agriculture, did not receive a position in Harding's administration.[61]

Continued Conservation

After leaving office in 1910, Pinchot took up leadership of the National Conservation Association (NCA), a conservationist non-governmental organization that he had helped found the previous year. The organization, which ceased operations in 1923, never attracted as many members as Pinchot had initially hoped, but its efforts affected conservation-related legislation.[62] Later in the 1920s, Pinchot worked with Senator George W. Norris to build a federal dam on the Tennessee River.[63]

Pinchot had appointed William Greeley during his tenure at the Forest Service, and Greeley became chief of the Forest Service in 1920.[27] Under Greeley, the forest service became a figurative fire engine company, protecting trees so the timber industry could cut them down later at government expense.[64] Pinchot had always preached of a "working forest" in which working people would engage in small-scale logging, while the forests would be preserved, and he was appalled by the large-scale logging undertaken by large syndicates.[65] Pinchot had a more favorable view of Greeley's successor, Robert Y. Stuart, and his influence played a key role in blocking several plans to transfer of the Forest Service out of the Department of Agriculture.[66]

First term as Governor of Pennsylvania

Governor William Cameron Sproul appointed Pinchot as chairman of the Pennsylvania Forest Commission in 1920. As chairman, Pinchot coaxed a major budget increase from the legislature, decentralized the commission's administration, and replaced numerous political appointees with professional foresters. He narrowly won the three-candidate Republican primary in Pennsylvania's 1922 gubernatorial election, and went on to defeat Democrat John A. McSparran in the general election.[67] Pinchot's victory over his Republican opponents owed much to his reputation as a staunch teetotaler during the early period of Prohibition; he was also boosted by his popularity with farmers, laborers, and women.[68] Pinchot focused on balancing the state budget; he inherited a $32 million deficit and left office with a $6.7 million surplus.[69] Pinchot and engineer Morris Llewellyn Cooke pursued ambitious plans to regulate Pennsylvania's electric power industry, but their proposals were defeated in the state legislature.[70]

Pinchot emerged as a potential contender for the Republican nomination in the 1924 presidential election following the death of President Harding, as many progressive Republicans hoped Pinchot could unseat Harding's successor, Calvin Coolidge. Pinchot's presidential chances were badly damaged by his role in settling the 1923 United Mine Workers coal strike, as he received the blame for a subsequent increase in coal prices, and Coolidge ultimately won the 1924 presidential election.[71] Constitutionally barred from seeking a second term, Pinchot ran in the 1926 Senate election in Pennsylvania. Facing strong opposition from anti-Prohibition "wets" and the conservative wing of the Republican Party, Pinchot was defeated by Congressman William Scott Vare in the Republican primary. Vare went on to defeat former Labor Secretary William Wilson in the general election, but in his capacity as governor Pinchot refused to certify the results of the election, claiming that Vare had illegally bought votes.[72] The Senate refused to seat Vare and the seat would not be filled until the appointment of Joseph R. Grundy in 1929.

Second term as governor

With the backing of Senator Grundy, Pinchot launched a bid for the Republican nomination in the 1930 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election. Relying once again on support from women and rural voters, Pinchot defeated Francis Shunk Brown, the candidate of Vare's Philadelphia machine, and Thomas Phillips, a former US Representative who was enthusiastically supported by the state's wet forces. Despite the defection of some Republicans, Pinchot narrowly defeated Democrat John Hemphill in the general election.[73] Taking office in the midst of the Great Depression, Pinchot faced persistently high unemployment levels and sharply declining revenues during his second term.[74]

Pinchot prioritized fiscal conservatism and avoided major budget increases, but he also sought ways to help the impoverished and unemployed. He presided over the passage of a bill to provide state money for indigent care and initiated various infrastructure projects.[75] He cooperated with President Franklin Roosevelt, despite Roosevelt's being a Democrat and Prohibition opponent. Under Governor Pinchot's leadership, Pennsylvania welcomed the Civilian Conservation Corps, which established 113 camps to work on public lands in Pennsylvania (second only to California). Working with the Works Progress Administration and National Park Service, Pinchot helped expand Pennsylvania's state parks, and also helped Pennsylvania's struggling farmers and unemployed workers by paving rural roads, which became known as "Pinchot Roads".[76][77]

Prohibition was repealed in 1933. Four days before the sale of alcohol became legal in Pennsylvania again, Pinchot called the Pennsylvania General Assembly into special session to debate regulations regarding the manufacture and sale of alcohol. This session led to the establishment of the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board and its system of state-run liquor stores. Though Pinchot is often misquoted as having said his goal was to "discourage the purchase of alcoholic beverages by making it as inconvenient and expensive as possible", in reality he believed that the PLCB would put bootleggers out of business by offering lower prices.[4] Pinchot also argued that under the new system of state controlled liquor stores "[w]hisky will be sold by civil service employees with exactly the same amount of salesmanship as is displayed by an automatic postage stamp vending machine."[78]

Final years

Pinchot ran unsuccessfully for the Senate a third time in the 1934 Senate election in Pennsylvania, losing the Republican nomination to incumbent Senator David A. Reed.[79][80] He later sought the Republican nomination in the 1938 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, running on a platform that favored the New Deal and opposed the influence of Republican leaders Joseph R. Grundy and Joseph N. Pew Jr. He was defeated in the Republican primary by conservative former Lieutenant Governor Arthur James.[81]

Out of public office, Pinchot continued his ultimately successful campaign to prevent the transfer of the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior, frequently sparring with Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes.[82][lower-alpha 3] He also published new editions of his manual on forestry[83] and worked on his autobiography, Breaking New Ground, which was published shortly after his death.[84] During and after World War II, Pinchot advocated for conservation to be a part of the mission of the United Nations, but the United Nations would not focus on the environment until the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.[85]

Personal life

During the 1912 presidential campaign, Pinchot frequently worked with Cornelia Bryce, a women's suffrage activist who was a daughter of former Congressman Lloyd Bryce and a granddaughter of former New York City mayor Edward Cooper. They became engaged in early 1914 and were married in August 1914.[87] Although Cornelia Pinchot waged several unsuccessful campaigns for the United States House of Representatives, she was successful with numerous other political and public service activities, and has been described by historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission as "one of the most politically active first ladies in the history of Pennsylvania".[86] She gave numerous speeches on behalf of women, organized labor, and other causes, and frequently served as a campaign surrogate for her husband.[88] Pinchot and his family took a seven-month voyage of the Southern Pacific Ocean in 1929, which Pinchot chronicled in his 1930 work, To the South Seas.[89]

Pinchot and his wife had one child, Gifford Bryce Pinchot, who was born in 1915.[90] The younger Pinchot later helped found the Natural Resources Defense Council, an organization similar to his father's National Conservation Association.[91] Proud of the first Gifford Pinchot's legacy, the family has continued to name their sons Gifford, down to Gifford Pinchot IV.[92]

Legacy

Gifford Pinchot National Forest in Washington and Gifford Pinchot State Park in Lewisberry, Pennsylvania, are named in his honor, as is Pinchot Hall at Penn State University. A large Coast Redwood in Muir Woods, California, is also named in his honor, as are Mount Pinchot and Pinchot Pass near the John Muir Trail in Kings Canyon National Park in the Sierra Nevada in California. The Pinchot Sycamore, the largest tree in his native state of Connecticut and second-largest sycamore on the Atlantic coast, still stands in Simsbury. The house where Pinchot was born belonged to his grandfather, Captain Elisha Phelps, and is also on the National Register of Historic Places.[93] He is also commemorated in the scientific name of a species of Caribbean lizard, Anolis pinchoti.[94] In 1963, President John F. Kennedy accepted the family's summer retreat house, Grey Towers National Historic Site, which the Pinchot family donated to the U.S. Forest Service. It remains the only National Historic Landmark operated by that federal agency.[95][96]

Gifford Pinchot III, grandson of the first Gifford Pinchot, founded the Pinchot University, now merged with Presidio Graduate School. The Pinchot family also dedicated The Pinchot Institute for Conservation, which maintains offices both at Grey Towers and headquarters in Washington, D.C. The Institute continues Pinchot's legacy of conservation leadership and sustainable forestry.

See also

- Mount Pinchot (Montana)

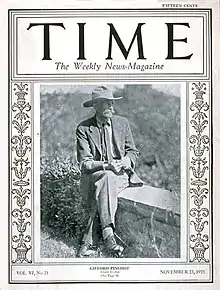

- List of covers of Time magazine (1920s) (November 23, 1925)

- Gifford Pinchot State Park a Pennsylvania state park in York County, Pennsylvania

- Gifford Pinchot National Forest, a United States National Forest in Washington

- National Irrigation Congress

- Pinchot South Sea Expedition

Notes

- Asked how to say his name, he told The Literary Digest "as though it were spelled pin'cho, with slight emphasis on the first syllable."[3]

- The Supreme Court upheld the Forest Service's power to control access to public land in the 1911 cases of United States v. Grimaud and United States v. Light.[42]

- The debate over the status of the Forest Service was part of a larger debate over the Brownlow Committee's recommendations to restructure the executive branch. Ickes sought to combine the Forest Service with the Department of the Interior to create a new Cabinet Department, the Department of Conservation.[82]

References

- "Taft Fears No Harm From Pinchot Row". The New York Times. January 9, 1910. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- "America's Chief Forester". The Mansfield Daily Shield. January 21, 1910. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- (Charles Earle Funk, What's the Name, Please?, Funk & Wagnalls, 1936)

- Madaio, Mike (October 2021). "Why Did Pennsylvania Become a Liquor Control State?". Pennsylvania Vine Company. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- Miller (2001), p. 58

- Johnson, Kirk (June 7, 2001). "From a Woodland Elegy, A Rhapsody in Green; Hunter Mountain Paintings Spurred Recovery". The New York Times.

- Miller (2001), pp. 30–34

- Miller (2001), pp. 53, 194

- Miller (2001), pp. 20–23

- Miller (2001), pp. 39–43

- Miller (2001), pp. 58, 190

- Miller (2001), pp. 58–60

- Pinchot, Gifford (1947). Breaking New Ground. Island Press (reprint, 1987). p. 1.

- Miller (2001), pp. 67–70

- Miller (2001), pp. 71–73

- Miller (2001), pp. 79–81

- America has been the context for both the origins of conservation history and its modern form, environmental history Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Asiaticsociety.org.bd. Retrieved on September 1, 2011.

- Miller (2001), pp. 83–90

- Rutkow, Eric (2012). American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation. New York: Scribner. pp. 153–157. ISBN 978-1-4391-9354-9.

- Miller (2001), pp. 101–102

- Miller (2001), pp. 125–127, 136; Clayton (2019), p. 225

- Miller (2001), p. 111

- Miller (2001), pp. 129–130

- Miller (2001), pp. 136–137

- Miller (2001), p. 134

- Miller (2001), p. 138

- "The Big Burn-Transcript". American Experience. PBS. February 3, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Lewis, James G. (1999). "The Pinchot Family and the Battle to Establish American Forestry". Pennsylvania History. 66 (2): 143–165. ISSN 0031-4528.

- Miller (2001), p. 156

- Miller (2001), pp. 155–156

- "Yale F&ES to Become the Yale School of the Environment". February 10, 2020.

- "The History of Forestry in America", p. 710, by W.N. Sparhawk in Trees: Yearbook of Agriculture, 1949. Washington, D.C.

- Ponder, Stephen (1987). "Gifford Pinchot, Press Agent for Forestry". Journal of Forest History. 31 (1): 26–35. doi:10.2307/4004839. ISSN 0094-5080. JSTOR 4004839. S2CID 163274398.

- Miller (2001), pp. 147–150

- Cooper (1990), p. 49

- Miller (2001), pp. 156–158

- Miller (2001), p. 155

- Miller (2001), p. 330

- The National Parks: America's Best Idea: Historical Figures. PBS. Retrieved on September 1, 2011.

- Balogh 2002

- Miller (2001), pp. 151–152, 159

- Miller (2001), pp. 159–161

- Cooper (1990), pp. 110–111

- Miller (2001), pp. 163–164

- Cooper (1990), pp. 111–112

- Cooper (1990), p. 155

- Rutkow, Eric (2012). American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation. New York: Scribner. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4391-9354-9.

- Coletta (1973), pp. 77–82

- Coletta (1973), pp. 85–86, 89

- Miller (2001), pp. 210–212

- Coletta (1973), pp. 89–92

- Miller (2001), pp. 214–217

- Miller (2001), pp. 218–221

- Miller (2001), pp. 231–233

- Miller (2001), pp. 234–235

- Miller (2001), pp. 245–246

- Miller (2001), pp. 236–237

- Fausold (1958), pp. 26–28

- Miller (2001), pp. 237–238

- Fausold (1958), p. 38

- McGeary (1959), pp. 341–342

- Miller (2001), pp. 226–228

- Miller (2001), pp. 274–276

- Egan (2009), pp. 270–271

- Egan (2009), p. 281

- Miller (2001), pp. 292, 341–344

- Miller (2001), pp. 249–250

- Miller (2001), pp. 251–254

- Miller (2001), pp. 260–261

- Miller (2001), pp. 269–270

- Zieger (1965), pp. 566–567

- Miller (2001), pp. 261–263

- Miller (2001), pp. 309–310

- Miller (2001), pp. 310–311

- Miller (2001), pp. 311–313

- First Pinchot Road Historical Marker, Explore PA History.com

- McClure, Jim. "First Pinchot Road in York County example of Great Depression-era stimulus project". York Daily Record. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Char Miller, ed. 2017. Gifford Pinchot: Selected Writings. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 173.

- Miller (2001), pp. 323–324

- Salter, John T. (1935). "Governor Pinchot and the Late Magistrate Stubbs". American Political Science Review. 29 (2): 249–256. doi:10.2307/1947505. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1947505. S2CID 144678282.

- Morgan (1978), pp. 198–202

- Miller (2001), pp. 351–356

- Miller (2001), pp. 333–335

- Miller (2001), pp. 361–365

- Miller (2001), pp. 372–375

- "Governor Gifford Pinchot | PHMC > Pennsylvania Governors".

- Miller (2001), pp. 177–180

- Miller (2001), p. 349

- Miller (2001), pp. 296–299

- Miller (2001), p. 204

- Miller (2001), pp. 357

- Tristan Baurick, "Pinchot embraces his family name, its calling", Kitsap Sun, October 22, 2011, available at "Pinchot embraces his family name, its calling » Kitsap Sun". Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2012.. Last accessed June 2, 2012.

- "Historic and Architectural Resources Inventory for the Town of Simsbury, Connecticut" (PDF). Town of Simsbury Connecticut. April 2010. p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Pinchot", pp. 207–208).

- "Grey Towers". United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Grey Towers". Grey Towers Heritage Association. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- International Plant Names Index. Pinchot.

Works cited

- Coletta, Paolo Enrico (1973). The Presidency of William Howard Taft. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700600960.

- Cooper Jr., John Milton (1990). Pivotal Decades: The United States, 1900-–1920. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393956559.

- Egan, Timothy (2009). The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt & the Fire That Saved America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-96841-1.

- Fausold, Martin L. (January 1958). "Gifford Pinchot and the Decline of Pennsylvania Progressivism". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 25 (1): 25–38. JSTOR 27769780.

- McGeary, M. Nelson (1959). "Gifford Pinchot's Years of Frustration, 1917–1920". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 83 (3): 327–342. JSTOR 20089210.

- Miller, Char (2001). Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-822-2.

- Morgan, Alfred L. (April 1978). "The Significance of Pennsylvania's 1938 Gubernatorial Election". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 102 (2): 184–211. JSTOR 20091255.

- Zieger, Robert H. (December 1965). "Pinchot and Coolidge: The Politics of the 1923 Anthracite Crisis". The Journal of American History. 52 (3): 566–581. doi:10.2307/1890848. JSTOR 1890848.

Bibliography

- Primary sources by Pinchot

- Breaking New Ground. 1947. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. In print, 1998, by Island Press and in paperback. ISBN 978-1-55963-670-4

- The Conservation Diaries of Gifford Pinchot. 2001. Edited by Harold K. Steen.

- The Fight for Conservation. 1910. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Secondary sources

- Balogh, Brian (2002). "Scientific Forestry and the Roots of the Modern American State: Gifford Pinchot's Path to Progressive Reform". Environmental History. 7 (2): 198–225. doi:10.2307/envhis/7.2.198. ISSN 1084-5453. JSTOR 3985682. S2CID 144639845.

- Bankoff, Greg (2009). "Breaking New Ground? Gifford Pinchot and the Birth of 'Empire Forestry' in the Philippines, 1900–1905". Environment and History. 15 (3): 369–393. doi:10.3197/096734009X12474738236078. JSTOR 20723737.

- Clayton, John (2019). Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America's Public Lands. Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1643130804.

- Forbes, Linda C. (2004). "A Vision for Cultivating a Nation: Gifford Pinchot's "The Fight for Conservation"". Organization & Environment. 17 (2): 226–231. doi:10.1177/1086026603256280. JSTOR 26162867. S2CID 144405438.

- Gould, Lewis L (2011), The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0700617746

- McCormick, John (1995). The Global Environmental Movement. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0471949404.

- McGeary, M. Nelson (1960). Gifford Pinchot: Forester-Politician. Princeton University Press.

- Meyer, John M. (1997). "Gifford Pinchot, John Muir, and the Boundaries of Politics in American Thought". Polity. 30 (2): 267–284. doi:10.2307/3235219. ISSN 0032-3497. JSTOR 3235219. S2CID 147180080.

- Miller, Nancy R. (2008). "Cornelia Bryce Pinchot and the Struggle for Protective Labor Legislation in Pennsylvania". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 132 (1): 33–64. JSTOR 20093980.

- Nash, Roderick (2014). Wilderness and the American Mind (5th ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300153507.

- Page, Walter H. (March 1910). "Gifford Pinchot, The Awakener Of A Nation". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XIX: 12662–12668. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- Smith, Michael B. (1998). "The Value of a Tree: Public Debates of John Muir and Gifford Pinchot". Historian. 60 (4): 757–778. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1998.tb01414.x. ISSN 0018-2370.

- Wild, Peter (1978). "4: Gifford Pinchott, Aristocrat". Pioneer Conservationists of Western America. Edward Abbey (Introduction). Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing. pp. 45–57. ISBN 0878421076.

Progressive Politics and Despotism Create the National Forests

- Online sources

- 1912: Competing Visions for America, Gifford Pinchot, Ohio State University

- Gifford Pinchot (1865–1948) Conservation Hall of Fame, National Wildlife Federation

- Gifford Pinchot Brief Bio

External links

- Gifford Pinchot at the Forest History Society

- Works by Gifford Pinchot at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Gifford Pinchot at Internet Archive

- Works by Gifford Pinchot at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The short film "Visions of the wild (1985)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive.

- "American Experience: The Big Burn"

- Grey Towers National Historical Site, Milford, Pennsylvania

- Pinchot Institute for Conservation, Washington, D.C.

- Gifford Pinchot at Find a Grave