Gold standard

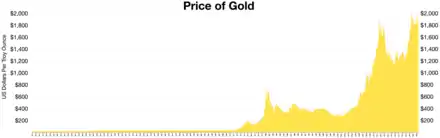

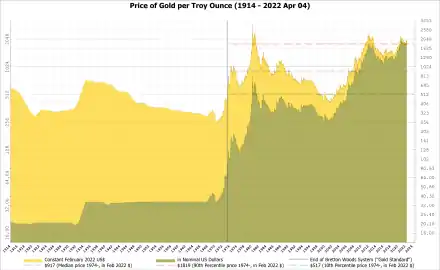

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the late 1920s to 1932[1][2] as well as from 1944 until 1971 when the United States unilaterally terminated convertibility of the US dollar to gold foreign central banks, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system.[3] Many states nonetheless hold substantial gold reserves.[4][5]

Historically, the silver standard and bimetallism have been more common than the gold standard.[6][7] The shift to an international monetary system based on a gold standard reflected accident, network externalities, and path dependence.[6] Great Britain accidentally adopted a de facto gold standard in 1717 when Sir Isaac Newton, then-master of the Royal Mint, set the exchange rate of silver to gold too low, thus causing silver coins to go out of circulation.[8] As Great Britain became the world's leading financial and commercial power in the 19th century, other states increasingly adopted Britain's monetary system.[8]

The gold standard was largely abandoned during the Great Depression before being re-instated in a limited form as part of the post-World War II Bretton Woods system. The gold standard was abandoned due to its propensity for volatility, as well as the constraints it imposed on governments: by retaining a fixed exchange rate, governments were hamstrung in engaging in expansionary policies to, for example, reduce unemployment during economic recessions.[9][10]

According to a survey of 39 economists, the majority (93 percent) agreed that a return to the gold standard would not improve price-stability and employment outcomes,[11] and two-thirds of economic historians reject the idea that the gold standard "was effective in stabilizing prices and moderating business-cycle fluctuations during the nineteenth century."[12] Nonetheless, according to economist Michael D. Bordo, the gold standard has three benefits: "its record as a stable nominal anchor; its automaticity; and its role as a credible commitment mechanism."[13]

Implementation

The United Kingdom slipped into a gold specie standard in 1717 by over-valuing gold at 15.2 times its weight in silver. It was unique among nations to use gold in conjunction with clipped, underweight silver shillings, addressed only before the end of the 18th century by the acceptance of gold proxies like token silver coins and banknotes.

From the more widespread acceptance of paper money in the 19th century emerged the gold bullion standard, a system where gold coins do not circulate, but authorities like central banks agree to exchange circulating currency for gold bullion at a fixed price. First emerging in the late 18th century to regulate exchange between London and Edinburgh, Keynes (1913) noted how such a standard became the predominant means of implementing the gold standard internationally in the 1870s.[14]

Restricting the free circulation of gold under the Classical Gold Standard period from the 1870s to 1914 was also needed in countries which decided implement the gold standard while guaranteeing the exchangeability of huge amounts of legacy silver coins into gold at the fixed rate (rather than valuing publicly-held silver at its depreciated value). The term limping standard is often used in countries maintaining significant amounts of silver coin at par with gold, thus an additional element of uncertainty with the currency's value versus gold. The most common silver coins kept at limping standard parity included French 5-franc coins, German 3-mark thalers, Dutch guilders, Indian rupees, and U.S. Morgan dollars.

Lastly, countries may implement a gold exchange standard, where the government guarantees a fixed exchange rate, not to a specified amount of gold, but rather to the currency of another country that is under a gold standard. This became the predominant international standard under the Bretton Woods Agreement from 1945 to 1971 by the fixing of world currencies to the U.S. dollar, the only currency after World War II to be on the gold bullion standard.

History before 1873

Silver and bimetallic standards until the 19th century

The use of gold as money began around 600 BCE in Asia Minor[15] and has been widely accepted ever since,[16] together with various other commodities used as money, with those that lose the least value over time becoming the accepted form.[17] In the early and high Middle Ages, the Byzantine gold solidus or bezant was used widely throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, but its use waned with the decline of the Byzantine Empire's economic influence.[18]

However, economic systems using gold as the sole currency and unit of account never emerged before the 18th century. For millennia it was silver, not gold, which was the real basis of the domestic economies: the foundation for most money-of-account systems, for payment of wages and salaries, and for most local retail trade. [19] Gold functioning as currency and unit of account for daily transactions was not possible due to various hindrances which were only solved by tools that emerged in the 19th century, among them:

- Divisibility: Gold as currency was hindered by its small size and rarity, with the dime-sized ducat of 3.4 grams representing 7 days’ salary for the highest-paid workers. In contrast, coins of silver and billon (low-grade silver) easily corresponded to daily labor costs and food purchases, making silver more effective as currency and unit of account. In mid-15th century England, most highly paid skilled artisans earned 6d a day (six pence, or 5.4 g silver), and a whole sheep cost 12d. This made the ducat of 40d and the half-ducat of 20d of little use for domestic trade.[19]

- Non-existence of token coinage for gold: Sargent and Velde (1997) explained how token coins of copper or billon exchangeable for silver or gold were almost non-existent before the 19th century. Small change was issued at almost full intrinsic value and without conversion provisions into specie. Tokens of little intrinsic value were widely mistrusted, were viewed as a precursor to currency devaluation, and were easily counterfeited in the pre-industrial era. This made the gold standard impossible anywhere with token silver coins; Britain itself only accepted the latter in the 19th century.[20]

- Non-existence of banknotes: Banknotes were mistrusted as currency in the first half of the 18th century following France's failed banknote issuance in 1716 under economist John Law. Banknotes only became accepted across Europe with the further maturing of banking institutions, and also as a result of the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century. Counterfeiting concerns also applied to banknotes.

The earliest European currency standards were therefore based on the silver standard, from the denarius of the Roman Empire, to the penny (denier) introduced by Charlemagne throughout Western Europe, to the Spanish dollar and the German Reichsthaler and Conventionsthaler which survived well into the 19th century. Gold functioned as a medium for international trade and high-value transactions, but it generally fluctuated in price versus everyday silver money.[19]

A bimetallic standard emerged under a silver standard in the process of giving popular gold coins like ducats a fixed value in terms of silver. In light of fluctuating gold-silver ratios in other countries, bimetallic standards were rather unstable and de facto transformed into a parallel bimetallic standard (where gold circulates at a floating exchange rate to silver) or reverted to a mono-metallic standard.[21] France was the most important country which maintained a bimetallic standard during most of the 19th century.

Gold standard origin in Britain

The English pound sterling introduced c 800 CE was initially a silver standard unit worth 20 shillings or 240 silver pennies. The latter initially contained 1.35 g fine silver, reducing by 1601 to 0.464 g (hence giving way to the shilling [12 pence] of 5.57 g fine silver). Hence the pound sterling was originally 324 g fine silver reduced to 111.36 g by 1601.

The problem of clipped, underweight silver pennies and shillings was a persistent, unresolved issue from the late 17th century to the early 19th century. In 1717 the value of the gold guinea (of 7.6885 g fine gold) was fixed at 21 shillings, resulting in a gold-silver ratio of 15.2 higher than prevailing ratios in Continental Europe. Great Britain was therefore de jure under a bimetallic standard with gold serving as the cheaper and more reliable currency compared to clipped silver[8] (full-weight silver coins did not circulate and went to Europe where 21 shillings fetched over a guinea in gold). Several factors helped extend the British gold standard into the 19th century, namely:

- The Brazilian Gold Rush of the 18th century supplying significant quantities of gold to Portugal and Britain, with Portuguese gold coins also legal tender in Britain.

- Ongoing trade deficits with China (which sold to Europe but had little use for European goods) drained silver from the economies of most of Europe. Combined with greater confidence in banknotes issued by the Bank of England, it opened the way for gold as well as banknotes becoming acceptable currency in lieu of silver.

- The acceptability of token / subsidiary silver coins as substitutes for gold before the end of the 18th century. Initially issued by the Bank of England and other private companies, permanent issuance of subsidiary coinage from the Royal Mint commenced after the Great Recoinage of 1816.

A proclamation from Queen Anne in 1704 introduced the British West Indies to the gold standard; however it did not result in the wide use of gold currency and the gold standard, given Britain's mercantilist policy of hoarding gold and silver from its colonies for use at home. Prices were quoted de jure in gold pounds sterling but were rarely paid in gold; the colonists' de facto daily medium of exchange and unit of account was predominantly the Spanish silver dollar.[22] Also explained in the history of the Trinidad and Tobago dollar.

Following the Napoleonic Wars, Britain legally moved from the bimetallic to the gold standard in the 19th century in several steps, namely:

- The 21-shilling guinea was discontinued in favor of the 20-shilling gold sovereign, or £1 coin, which contained 7.32238 g fine gold

- The permanent issuance of subsidiary, limited legal tender silver coinage, commencing with the Great Recoinage of 1816

- The 1819 Act for the Resumption of Cash Payments, which set 1823 as the date for resumption of convertibility of Bank of England banknotes into gold sovereigns, and

- The Peel Banking Act of 1844, which institutionalized the gold standard in Britain by establishing a ratio between gold reserves held by the Bank of England versus the banknotes which it could issue, and by significantly curbing the privilege of other British banks to issue banknotes.

From the second half of the 19th century Britain then introduced its gold standard to Australia, New Zealand, and the British West Indies in the form of circulating gold sovereigns as well as banknotes that were convertible at par into sovereigns or Bank of England banknotes.[8] Canada introduced its own gold dollar in 1867 at par with the U.S. gold dollar and with a fixed exchange rate to the gold sovereign.[23]

Effects of the 19th century gold rush

.jpg.webp)

Up until 1850 only Britain and a few of its colonies were on the gold standard, with the majority of other countries being on the silver standard. France and the United States were two of the more notable countries on the bimetallic standard. France's actions in maintaining the French franc at either 4.5 g fine silver or 0.29032 g fine gold stabilized world gold-silver price ratios close to the French ratio of 15.5 in the first three quarters of the 19th century by offering to mint the cheaper metal in unlimited quantities – gold 20-franc coins whenever the ratio is below 15.5, and silver 5-franc coins whenever the ratio is above 15.5. The United States dollar was also bimetallic de jure until 1900, worth either 24.0566 g fine silver, or 1.60377 g fine gold (ratio 15.0); the latter revised to 1.50463 g fine gold (ratio 15.99) from 1837 to 1934. The silver dollar was generally the cheaper currency before 1837, while the gold dollar was cheaper between 1837 and 1873.

The nearly-coincidental California gold rush of 1849 and the Australian gold rushes of 1851 significantly increased world gold supplies and the minting of gold francs and dollars as the gold-silver ratio went below 15.5, pushing France and the United States into the gold standard with Great Britain during the 1850s. The benefits of the gold standard were first felt by this larger bloc of countries, with Britain and France being the world's leading financial and industrial powers of the 19th century while the United States was an emerging power.

By the time the gold-silver ratio reverted to 15.5 in the 1860s, this bloc of gold-utilizing countries grew further and provided momentum to an international gold standard before the end of the 19th century.

- Portugal and several British colonies commenced with the gold standard in the 1850s and 1860s

- France was joined by Belgium, Switzerland and Italy in a larger Latin Monetary Union based on both the gold and silver French francs.

- Several international monetary conferences during the 1860s began to consider the merits of an international gold standard, albeit with concerns on its impact on the price of silver should several countries make the switch.[24]

The international classical gold standard, 1873–1914

Rollout in Europe and the United States

The international classical gold standard commenced in 1873 after the German Empire decided to transition from the silver North German thaler and South German gulden to the German gold mark, reflecting the sentiment of the monetary conferences of the 1860s, and utilizing the 5 billion gold francs (worth 4.05 billion marks or 1,451 metric tons) in indemnity demanded from France at the end of the Franco-Prussian War. This transition done by a large, centrally located European economy also triggered a switch to gold by several European countries in the 1870s, and led as well to the suspension of the unlimited minting of silver 5-franc coins in the Latin Monetary Union in 1873.[25]

The following countries switched from silver or bimetallic currencies to gold in the following years (Britain is included for completeness):

- 1816, British Empire: one pound: from 111.37 g silver to 7.32238 g gold; ratio 15.21

- 1873, German Empire: one North German thaler or 13⁄4 South German gulden of 16.67 g silver, converted to 3 German gold marks of 3/2.79 = 1.0753 g gold; ratio 15.5

- 1873, Latin Monetary Union franc: from 4.5 g silver to 9/31 = 0.29032 g gold; ratio 15.5

- 1873, United States dollar, by the Coinage Act of 1873: from 24.0566 g silver to 1.50463 g gold; ratio 15.99

- 1875, Scandinavian Monetary Union: Rigsdaler specie of 25.28 g silver, converted to 4 krone (or krona) of 4/2.48 = 1.6129 g gold; ratio 15.67

- 1875, Netherlands: the Dutch Guilder from 9.45 g silver to 0.6048 g gold; ratio 15.625.

- 1892, Austria–Hungary: the Austro-Hungarian florin of 11.11 g silver, converted to two Austro-Hungarian krone of 2/3.28 = 0.60976 g gold; ratio 18.22

- 1897, Russian Empire: the ruble from 18 g silver to 0.7742 g gold; ratio 23.25.

The gold standard became the basis for the international monetary system after 1873.[26][27] According to economic historian Barry Eichengreen, "only then did countries settle on gold as the basis for their money supplies. Only then were pegged exchange rates based on the gold standard firmly established."[26] Adopting and maintaining a singular monetary arrangement encouraged international trade and investment by stabilizing international price relationships and facilitating foreign borrowing.[27] [28] The gold standard was not firmly established in non-industrial countries.[29]

Central banks and the gold exchange standard

As feared by the various international monetary conferences of the 1860s, the switch to gold, combined with record U.S. silver output from the Comstock Lode, plunged the price of silver after 1873 with the gold-silver ratio climbing to historic highs of 18 by 1880. Most of continental Europe made the conscious decision to move to the gold standard while leaving the mass of legacy (and erstwhile depreciated) silver coins remaining unlimited legal tender and convertible at face value for new gold currency. The term limping standard was used to describe currencies whose nations’ commitment to the gold standard was put into doubt by the huge mass of silver coins still tendered for payment, the most numerous of which were French 5-franc coins, German 3-mark Vereinsthalers, Dutch guilders and American Morgan dollars. [30]

Britain's original gold specie standard with gold in circulation was not feasible anymore with the rest of Continental Europe also switching to gold. The problem of scarce gold and legacy silver coins was only resolved by national central banks taking over the replacement of silver with national bank notes and token coins, centralizing the nation's supply of scarce gold, providing for reserve assets to guarantee convertibility of legacy silver coins, and allowing the conversion of banknotes into gold bullion or other gold-standard currencies solely for external purchases. This system is known as either a gold bullion standard whenever gold bars are offered, or a gold exchange standard whenever other gold-convertible currencies are offered.

John Maynard Keynes referred to both standards above as simply the gold exchange standard in his 1913 book Indian Currency and Finance. He described this as the predominant form of the international gold standard before the First World War, that a gold standard was generally impossible to implement before the 19th century due to the absence of recently developed tools (like central banking institutions, banknotes, and token currencies), and that a gold exchange standard was even superior to Britain's gold specie standard with gold in circulation. As discussed by Keynes:[14]

The Gold-Exchange Standard arises out of the discovery that, so long as gold is available for payments of international indebtedness at an approximately constant rate in terms of the national currency, it is a matter of comparative indifference whether it actually forms the national currency ... The Gold-Exchange Standard may be said to exist when gold does not circulate in a country to an appreciable extent, when the local currency is not necessarily redeemable in gold, but when the Government or Central Bank makes arrangements for the provision of foreign remittances in gold at a fixed maximum rate in terms of the local currency, the reserves necessary to provide these remittances being kept to a considerable extent abroad.

Its theoretical advantages were first set forth by Ricardo (i.e. David Ricardo, 1824) at the time of the Bullionist Controversy. He laid it down that a currency is in its most perfect state when it consists of a cheap material, but having an equal value with the gold it professes to represent; and he suggested that convertibility for the purposes of the foreign exchanges should be ensured by the tendering on demand of gold bars (not coin) in exchange for notes, so that gold might be available for purposes of export only, and would be prevented from entering into the internal circulation of the country.

The first crude attempt in recent times at establishing a standard of this type was made by Holland. The free coinage of silver was suspended in 1877. But the currency continued to consist mainly of silver and paper. It has been maintained since that date at a constant value in terms of gold by the Bank's regularly providing gold when it is required for export and by its using its authority at the same time for restricting so far as possible the use of gold at home. To make this policy possible, the Bank of Holland has kept a reserve, of a moderate and economical amount, partly in gold, partly in foreign bills.

Since the Indian system (gold exchange standard implemented in 1893) has been perfected and its provisions generally known, it has been widely imitated both in Asia and elsewhere ... Something similar has existed in Java under Dutch influences for many years ... The Gold-Exchange Standard is the only possible means of bringing China onto a gold basis ...

The classical gold standard of the late 19th century was therefore not merely a superficial switch from circulating silver to circulating gold. The bulk of silver currency was actually replaced by banknotes and token currency whose gold value was guaranteed by gold bullion and other reserve assets held inside central banks. In turn, the gold exchange standard was just one step away from modern fiat currency with banknotes issued by central banks, and whose value is secured by the bank's reserve assets, but whose exchange value is determined by the central bank's monetary policy objectives on its purchasing power in lieu of a fixed equivalence to gold.

Rollout outside Europe

The final chapter of the classical gold standard ending in 1914 saw the gold exchange standard extended to many Asian countries by fixing the value of local currencies to gold or to the gold standard currency of a Western colonial power. The Netherlands East Indies guilder was the first Asian currency pegged to gold in 1875 via a gold exchange standard which maintained its parity with the gold Dutch guilder.

Various international monetary conferences were called up before 1890, with various countries actually pledging to maintain the limping standard of freely circulating legacy silver coins in order to prevent the further deterioration of the gold–silver ratio which reached 20 in the 1880s.[30] After 1890 however, silver's price decline could not be prevented further and the gold–silver ratio rose sharply above 30.

In 1893 the Indian rupee of 10.69 g fine silver was fixed at 16 British pence (or £1 = 15 rupees; gold-silver ratio 21.9), with legacy silver rupees remaining legal tender. In 1906 the Straits dollar of 24.26 g silver was fixed at 28 pence (or £1 = 84⁄7 dollars; ratio 28.4).

Nearly similar gold standards were implemented in Japan in 1897, in the Philippines in 1903, and in Mexico in 1905 when the previous yen or peso of 24.26 g silver was redefined to approximately 0.75 g gold or half a U.S. dollar (ratio 32.3). Japan gained the needed gold reserves after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895. For Japan, moving to gold was considered vital for gaining access to Western capital markets.[31]

"Rules of the Game"

In the 1920s John Maynard Keynes retrospectively developed the phrase "rules of the game" to describe how central banks would ideally implement a gold standard during the prewar classical era, assuming international trade flows followed the ideal price–specie flow mechanism. Violations of the "rules" actually observed during the classical gold standard era from 1873 to 1914, however, reveal how much more powerful national central banks actually are in influencing price levels and specie flows, compared to the "self-correcting" flows predicted by the price-specie flow mechanism.[32]

Keynes premised the "rules of the game" on best practices of central banks to implement the pre-1914 international gold standard, namely:

- To substitute gold with fiat currency in circulation, so that gold reserves may be centralized

- To actually allow a prudently-determined ratio of gold reserves to fiat currency of less than 100%, with the difference made up by other loans and invested assets, such reserve ratio amounts consistent with fractional reserve banking practices

- To exchange circulating currency for gold or other foreign currencies at a fixed gold price, and to freely permit gold imports and exports

- Central banks were actually allowed modest margins in exchange rates to reflect gold delivery costs while still adhering to the gold standard. To illustrate this point, France may ideally allow the pound sterling (worth 25.22 francs based on ratios of their gold content) to trade between so-called gold points of 25.02F to 25.42F (plus or minus an assumed 0.20F/£ in gold delivery costs). France prevents sterling from climbing above 25.42F by delivering gold worth 25.22F or £1 (spending 0.20F for delivery), and from falling below 25.02F by the reverse process of ordering £1 in gold worth 25.22F in France (and again, minus 0.20F in costs).

- Finally, central banks were authorized to suspend the gold standard in times of war until it could be restored again as the contingency subsides.

Central banks were also expected to maintain the gold standard on the ideal assumption of international trade operating under the price–specie flow mechanism proposed by economist David Hume wherein:

- Countries which exported more goods would receive specie (gold or silver) inflows, at the expense of countries which imported those goods.

- More specie in exporting countries will result in higher price levels there, and conversely in lower price levels amongst countries spending their specie.

- Price disparities will self-correct as lower prices in specie-deficient will attract spending from specie-rich countries, until price levels in both places equalize again.

In practice, however, specie flows during the classical gold standard era failed to exhibit the self-corrective behavior described above. Gold finding its way back from surplus to deficit countries to exploit price differences was a painfully slow process, and central banks found it far more effective to raise or lower domestic price levels by lowering or raising domestic interest rates. High price level countries may raise interest rates to lower domestic demand and prices, but it may also trigger gold inflows from investors – contradicting the premise that gold will flow out of countries with high price levels. Developed economies deciding to buy or sell domestic assets to international investors also turned out to be more effective in influencing gold flows than the self-correcting mechanism predicted by Hume.[32]

Another set of violations to the "rules of the game" involved central banks not intervening in a timely manner even as exchange rates went outside the "gold points" (in the example above, cases existed of the pound climbing above 25.42 francs or falling below 25.02 francs). Central banks were found to pursue other objectives other than fixed exchange rates to gold (like e.g. lower domestic prices, or stopping huge gold outflows), though such behavior is limited by public credibility on their adherence to the gold standard. Keynes described such violations occurring before 1913 by French banks limiting gold payouts to 200 francs per head and charging a 1% premium, and by the German Reichsbank partially suspending free payment in gold, though "covertly and with shame".[14]

Some countries had limited success in implementing the gold standard even while disregarding such "rules of the game" in its pursuit of other monetary policy objectives. Inside the Latin Monetary Union, the Italian lira and the Spanish peseta traded outside typical gold-standard levels of 25.02–25.42F/£ for extended periods of time.[33]

- Italy tolerated in 1866 the issuance of corso forzoso (forced legal tender paper currency) worth less than the Latin Monetary Union franc. It also flooded the Union with low-valued subsidiary silver coins worth less than the franc. For the rest of the 19th century the Italian lira traded at a fluctuating discount versus the standard gold franc.

- In 1883 the Spanish peseta went off the gold standard and traded below parity with the gold French franc. However, as the free minting of silver was suspended to the general public, the peseta had a floating exchange rate between the value of the gold franc and the silver franc. The Spanish government captured all profits from minting duros (5-peseta coins) out of silver bought for less than 5 ptas. While total issuance was limited to prevent the peseta from falling below the silver franc, the abundance of duros in circulation prevented the peseta from returning at par with the gold franc. Spain's system where the silver duro traded at a premium above its metallic value due to relative scarcity is called the fiduciary standard, and was similarly implemented in the Philippines and other Spanish colonies in the end of the 19th century.[34]

In the United States

Inception

John Hull was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to make the earliest coinage of the colony, the willow, the oak, and the pine tree shilling in 1652, once again based on the silver standard. [35]

In the 1780s, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Morris and Alexander Hamilton recommended to Congress that a decimal currency system be adopted by the United States. The initial recommendation in 1785 was a silver standard based on the Spanish milled dollar (finalized at 371.25 grains or 24.0566 g fine silver), but in the final version of the Coinage Act of 1792 Hamilton's recommendation to include a $10 gold eagle was also approved, containing 247.5 grains (16.0377 g) fine gold. Hamilton therefore put the U.S. dollar on a bimetallic standard with a gold-silver ratio of 15.0.[36]

American-issued dollars and cents remained less common in circulation than Spanish dollars and reales (1/8th dollar) for the next six decades until foreign currency was demonetized in 1857. $10 gold eagles were exported to Europe where it could fetch over ten Spanish dollars due to their higher gold ratio of 15.5. American silver dollars also compared favorably with Spanish dollars and were easily used for overseas purchases. In 1806 President Jefferson suspended the minting of exportable gold coins and silver dollars in order to divert the United States Mint’s limited resources into fractional coins which stayed in circulation.

Pre-Civil War

The United States also embarked on establishing a national bank with the First Bank of the United States in 1791 and the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. In 1836, President Andrew Jackson failed to extend the Second Bank's charter, reflecting his sentiments against banking institutions as well as his preference for the use of gold coins for large payments rather than privately-issued banknotes. The return of gold could only be possible by reducing the dollar's gold equivalence, and in the Coinage Act of 1834 the gold-silver ratio was increased to 16.0 (ratio finalized in 1837 to 15.99 when the fine gold content of the $10 eagle was set at 232.2 grains or 15.0463 g).

Gold discoveries in California in 1848 and later in Australia lowered the gold price relative to silver; this drove silver money from circulation because it was worth more in the market than as money.[37] Passage of the Independent Treasury Act of 1848 placed the U.S. on a strict hard-money standard. Doing business with the American government required gold or silver coins.

Government accounts were legally separated from the banking system. However, the mint ratio (the fixed exchange rate between gold and silver at the mint) continued to overvalue gold. In 1853, silver coins 50 cents and below were reduced in silver content and cannot be requested for minting by the general public (only the U.S. government can request for it). In 1857 the legal tender status of Spanish dollars and other foreign coinage was repealed. In 1857 the final crisis of the free banking era began as American banks suspended payment in silver, with ripples through the developing international financial system.

Post-Civil War

Due to the inflationary finance measures undertaken to help pay for the U.S. Civil War, the government found it difficult to pay its obligations in gold or silver and suspended payments of obligations not legally specified in specie (gold bonds); this led banks to suspend the conversion of bank liabilities (bank notes and deposits) into specie. In 1862 paper money was made legal tender. It was a fiat money (not convertible on demand at a fixed rate into specie). These notes came to be called "greenbacks".[37]

After the Civil War, Congress wanted to reestablish the metallic standard at pre-war rates. The market price of gold in greenbacks was above the pre-War fixed price ($20.67 per ounce of gold) requiring deflation to achieve the pre-War price. This was accomplished by growing the stock of money less rapidly than real output. By 1879 the market price of the greenback matched the mint price of gold, and according to Barry Eichengreen, the United States was effectively on the gold standard that year.[25]

The Coinage Act of 1873 (also known as the Crime of ‘73) suspended the minting of the standard silver dollar (of 412.5 grains, 90% fine), the only fully legal tender coin that individuals could convert silver bullion into in unlimited (or Free silver) quantities, and right at the onset of the silver rush from the Comstock Lode in the 1870s. Political agitation over the inability of silver miners to monetize their produce resulted in the Bland–Allison Act of 1878 and Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 which made compulsory the minting of significant quantities of the silver Morgan dollar.

With the resumption of convertibility on June 30, 1879, the government again paid its debts in gold, accepted greenbacks for customs and redeemed greenbacks on demand in gold. While greenbacks made suitable substitutes for gold coins, American implementation of the gold standard was hobbled by the continued over-issuance of silver dollars and silver certificates emanating from political pressures. Lack of public confidence in the ubiquitous silver currency resulted in a run on U.S. gold reserves during the Panic of 1893.

During the latter part of the nineteenth century the use of silver and a return to the bimetallic standard were recurrent political issues, raised especially by William Jennings Bryan, the People's Party and the Free Silver movement. In 1900 the gold dollar was declared the standard unit of account and a gold reserve for government issued paper notes was established. Greenbacks, silver certificates, and silver dollars continued to be legal tender, all redeemable in gold.[37]

Fluctuations in the U.S. gold stock, 1862–1877

| US gold stock | |

|---|---|

| 1862 | 59 tons |

| 1866 | 81 tons |

| 1875 | 50 tons |

| 1878 | 78 tons |

The U.S. had a gold stock of 1.9 million ounces (59 t) in 1862. Stocks rose to 2.6 million ounces (81 t) in 1866, declined in 1875 to 1.6 million ounces (50 t) and rose to 2.5 million ounces (78 t) in 1878. Net exports did not mirror that pattern. In the decade before the Civil War net exports were roughly constant; postwar they varied erratically around pre-war levels, but fell significantly in 1877 and became negative in 1878 and 1879. The net import of gold meant that the foreign demand for American currency to purchase goods, services, and investments exceeded the corresponding American demands for foreign currencies. In the final years of the greenback period (1862–1879), gold production increased while gold exports decreased. The decrease in gold exports was considered by some to be a result of changing monetary conditions. The demands for gold during this period were as a speculative vehicle, and for its primary use in the foreign exchange markets financing international trade. The major effect of the increase in gold demand by the public and Treasury was to reduce exports of gold and increase the Greenback price of gold relative to purchasing power.[38]

Abandonment of the gold standard

Impact of World War I

Governments with insufficient tax revenue suspended convertibility repeatedly in the 19th century. The real test, however, came in the form of World War I, a test which "it failed utterly" according to economist Richard Lipsey.[16] The gold specie standard came to an end in the United Kingdom and the rest of the British Empire with the outbreak of World War I.[39]

By the end of 1913, the classical gold standard was at its peak but World War I caused many countries to suspend or abandon it.[40] According to Lawrence Officer the main cause of the gold standard's failure to resume its previous position after World War I was "the Bank of England's precarious liquidity position and the gold-exchange standard". A run on sterling caused Britain to impose exchange controls that fatally weakened the standard; convertibility was not legally suspended, but gold prices no longer played the role that they did before.[41] In financing the war and abandoning gold, many of the belligerents suffered drastic inflations. Price levels doubled in the U.S. and Britain, tripled in France and quadrupled in Italy. Exchange rates changed less, even though European inflation rates were more severe than America's. This meant that the costs of American goods decreased relative to those in Europe. Between August 1914 and spring of 1915, the dollar value of U.S. exports tripled and its trade surplus exceeded $1 billion for the first time.[42]

Ultimately, the system could not deal quickly enough with the large deficits and surpluses; this was previously attributed to downward wage rigidity brought about by the advent of unionized labor, but is now considered as an inherent fault of the system that arose under the pressures of war and rapid technological change. In any case, prices had not reached equilibrium by the time of the Great Depression, which served to kill off the system completely.[16]

For example, Germany had gone off the gold standard in 1914, and could not effectively return to it because war reparations had cost it much of its gold reserves. During the occupation of the Ruhr the German central bank (Reichsbank) issued enormous sums of non-convertible marks to support workers who were on strike against the French occupation and to buy foreign currency for reparations; this led to the German hyperinflation of the early 1920s and the decimation of the German middle class.

The U.S. did not suspend the gold standard during the war. The newly created Federal Reserve intervened in currency markets and sold bonds to "sterilize" some of the gold imports that would have otherwise increased the stock of money. By 1927 many countries had returned to the gold standard.[37] As a result of World War I the United States, which had been a net debtor country, had become a net creditor by 1919.[43]

Interwar period

The gold specie standard ended in the United Kingdom and the rest of the British Empire at the outbreak of World War I, when Treasury notes replaced the circulation of gold sovereigns and gold half sovereigns. Legally, the gold specie standard was not abolished. The end of the gold standard was successfully effected by the Bank of England through appeals to patriotism urging citizens not to redeem paper money for gold specie. It was only in 1925, when Britain returned to the gold standard in conjunction with Australia and South Africa, that the gold specie standard was officially ended.

The British Gold Standard Act 1925 both introduced the gold bullion standard and simultaneously repealed the gold specie standard.[44] The new standard ended the circulation of gold specie coins. Instead, the law compelled the authorities to sell gold bullion on demand at a fixed price, but "only in the form of bars containing approximately four hundred ounces troy [12 kg] of fine gold".[45][46] John Maynard Keynes, citing deflationary dangers, argued against resumption of the gold standard.[47] By fixing the price at a level which restored the pre-war exchange rate of US$4.86 per pound sterling, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Churchill is argued to have made an error that led to depression, unemployment and the 1926 general strike. The decision was described by Andrew Turnbull as a "historic mistake".[48]

The pound left the gold standard in 1931 and a number of currencies of countries that historically had performed a large amount of their trade in sterling were pegged to sterling instead of to gold. The Bank of England took the decision to leave the gold standard abruptly and unilaterally.[49]

Great Depression

Many other countries followed Britain in returning to the gold standard, leading to a period of relative stability but also deflation.[51] This state of affairs lasted until the Great Depression (1929–1939) forced countries off the gold standard.[29] Primary-producing countries were first to abandon the gold standard.[29] In the summer of 1931, a Central European banking crisis led Germany and Austria suspend gold convertibility and impose exchange controls.[29] A May 1931 run on Austria's largest commercial bank had caused it to fail. The run spread to Germany, where the central bank also collapsed. International financial assistance was too late and in July 1931 Germany adopted exchange controls, followed by Austria in October. The Austrian and German experiences, as well as British budgetary and political difficulties, were among the factors that destroyed confidence in sterling, which occurred in mid-July 1931. Runs ensued and the Bank of England lost much of its reserves.

On September 19, 1931, speculative attacks on the pound led the Bank of England to abandon the gold standard, ostensibly "temporarily".[49] However, the ostensibly temporary departure from the gold standard had unexpectedly positive effects on the economy, leading to greater acceptance of departing from the gold standard.[49] Loans from American and French central banks of £50 million were insufficient and exhausted in a matter of weeks, due to large gold outflows across the Atlantic.[52][53][54] The British benefited from this departure. They could now use monetary policy to stimulate the economy. Australia and New Zealand had already left the standard and Canada quickly followed suit.

The interwar partially-backed gold standard was inherently unstable because of the conflict between the expansion of liabilities to foreign central banks and the resulting deterioration in the Bank of England's reserve ratio. France was then attempting to make Paris a world class financial center, and it received large gold flows as well.[55]

Upon taking office in March 1933, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt departed from the gold standard.[56]

By the end of 1932, the gold standard had been abandoned as a global monetary system.[56] Czechoslovakia, Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland abandoned the gold standard in the mid-1930s.[56] According to Barry Eichengreen, there were three primary reasons for the collapse of the gold standard:[57]

- Tradeoffs between currency stability and other domestic economic objectives: Governments in the 1920s and 1930s faced conflictual pressures between maintaining currency stability and reducing unemployment. Suffrage, trade unions, and labor parties pressured governments to focus on reducing unemployment rather than maintaining currency stability.

- Increased risk of destabilizing capital flight: International finance doubted the credibility of national governments to maintain currency stability, which led to capital flight during crises, which aggravated the crises.

- The U.S., not Britain, was the main financial center: Whereas Britain had during past periods been capable of managing a harmonious international monetary system, the U.S. was not.

Causes of the Great Depression

Economists, such as Barry Eichengreen, Peter Temin and Ben Bernanke, blame the gold standard of the 1920s for prolonging the economic depression which started in 1929 and lasted for about a decade.[58][59][60][61][62] The gold standard theory of the Depression has been described as the "consensus view" among economists.[63][64] This view is based on two arguments: "(1) Under the gold standard, deflationary shocks were transmitted between countries and, (2) for most countries, continued adherence to gold prevented monetary authorities from offsetting banking panics and blocked their recoveries."[63] However, a 2002 paper argues that the second argument would only apply "to small open economies with limited gold reserves. This was not the case for the United States, the largest country in the world, holding massive gold reserves. The United States was not constrained from using expansionary policy to offset banking panics, deflation, and declining economic activity."[63] According to Edward C. Simmons, in the United States, adherence to the gold standard prevented the Federal Reserve from expanding the money supply to stimulate the economy, fund insolvent banks and fund government deficits that could "prime the pump" for an expansion. Once off the gold standard, it became free to engage in such money creation. The gold standard limited the flexibility of the central banks' monetary policy by limiting their ability to expand the money supply. In the US, the central bank was required by the Federal Reserve Act (1913) to have gold backing 40% of its demand notes.[65]

Higher interest rates intensified the deflationary pressure on the dollar and reduced investment in U.S. banks. Commercial banks converted Federal Reserve Notes to gold in 1931, reducing its gold reserves and forcing a corresponding reduction in the amount of currency in circulation. This speculative attack created a panic in the U.S. banking system. Fearing imminent devaluation many depositors withdrew funds from U.S. banks.[66] As bank runs grew, a reverse multiplier effect caused a contraction in the money supply.[67] Additionally the New York Fed had loaned over $150 million in gold (over 240 tons) to European Central Banks. This transfer contracted the U.S. money supply. The foreign loans became questionable once Britain, Germany, Austria and other European countries went off the gold standard in 1931 and weakened confidence in the dollar.[68]

The forced contraction of the money supply resulted in deflation. Even as nominal interest rates dropped, deflation-adjusted real interest rates remained high, rewarding those who held onto money instead of spending it, further slowing the economy.[69] Recovery in the United States was slower than in Britain, in part due to Congressional reluctance to abandon the gold standard and float the U.S. currency as Britain had done.[70]

In the early 1930s, the Federal Reserve defended the dollar by raising interest rates, trying to increase the demand for dollars. This helped attract international investors who bought foreign assets with gold.[66]

Congress passed the Gold Reserve Act on 30 January 1934; the measure nationalized all gold by ordering Federal Reserve banks to turn over their supply to the U.S. Treasury. In return, the banks received gold certificates to be used as reserves against deposits and Federal Reserve notes. The act also authorized the president to devalue the gold dollar. Under this authority, the president, on 31 January 1934, changed the value of the dollar from $20.67 to the troy ounce to $35 to the troy ounce, a devaluation of over 40%.

Other factors in the prolongation of the Great Depression include trade wars and the reduction in international trade caused by barriers such as Smoot–Hawley Tariff in the U.S. and the Imperial Preference policies of Great Britain, the failure of central banks to act responsibly,[71] government policies designed to prevent wages from falling, such as the Davis–Bacon Act of 1931, during the deflationary period resulting in production costs dropping slower than sales prices, thereby injuring business profits[72] and increases in taxes to reduce budget deficits and to support new programs such as Social Security. The U.S. top marginal income tax rate went from 25% to 63% in 1932 and to 79% in 1936,[73] while the bottom rate increased over tenfold, from .375% in 1929 to 4% in 1932.[74] The concurrent massive drought resulted in the U.S. Dust Bowl.

The Austrian School aruged that the Great Depression was the result of a credit bust.[75] Alan Greenspan wrote that the bank failures of the 1930s were sparked by Great Britain dropping the gold standard in 1931. This act "tore asunder" any remaining confidence in the banking system.[76] Financial historian Niall Ferguson wrote that what made the Great Depression truly 'great' was the European banking crisis of 1931.[77] According to Federal Reserve Chairman Marriner Eccles, the root cause was the concentration of wealth resulting in a stagnating or decreasing standard of living for the poor and middle class. These classes went into debt, producing the credit explosion of the 1920s. Eventually, the debt load grew too heavy, resulting in the massive defaults and financial panics of the 1930s.[78]

Bretton Woods

Under the Bretton Woods international monetary agreement of 1944, the gold standard was kept without domestic convertibility. The role of gold was severely constrained, as other countries' currencies were fixed in terms of the dollar. Many countries kept reserves in gold and settled accounts in gold. Still, they preferred to settle balances with other currencies, with the US dollar becoming the favorite. The International Monetary Fund was established to help with the exchange process and assist nations in maintaining fixed rates. Within Bretton Woods adjustment was cushioned through credits that helped countries avoid deflation. Under the old standard, a country with an overvalued currency would lose gold and experience deflation until the currency was again valued correctly. Most countries defined their currencies in terms of dollars, but some countries imposed trading restrictions to protect reserves and exchange rates. Therefore, most countries' currencies were still basically inconvertible. In the late 1950s, the exchange restrictions were dropped and gold became an important element in international financial settlements.[37]

After the Second World War, a system similar to a gold standard and sometimes described as a "gold exchange standard" was established by the Bretton Woods Agreements. Under this system, many countries fixed their exchange rates relative to the U.S. dollar and central banks could exchange dollar holdings into gold at the official exchange rate of $35 per ounce; this option was not available to firms or individuals. All currencies pegged to the dollar thereby had a fixed value in terms of gold.[16]

Starting in the 1959–1969 administration of President Charles de Gaulle and continuing until 1970, France reduced its dollar reserves, exchanging them for gold at the official exchange rate, reducing U.S. economic influence. This, along with the fiscal strain of federal expenditures for the Vietnam War and persistent balance of payments deficits, led U.S. President Richard Nixon to end international convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold on August 15, 1971 (the "Nixon Shock").

This was meant to be a temporary measure, with the gold price of the dollar and the official rate of exchanges remaining constant. Revaluing currencies was the main purpose of this plan. No official revaluation or redemption occurred. The dollar subsequently floated. In December 1971, the "Smithsonian Agreement" was reached. In this agreement, the dollar was devalued from $35 per troy ounce of gold to $38. Other countries' currencies appreciated. However, gold convertibility did not resume. In October 1973, the price was raised to $42.22. Once again, the devaluation was insufficient. Within two weeks of the second devaluation the dollar was left to float. The $42.22 par value was made official in September 1973, long after it had been abandoned in practice. In October 1976, the government officially changed the definition of the dollar; references to gold were removed from statutes. From this point, the international monetary system was made of pure fiat money. However, gold has persisted as a significant reserve asset since the collapse of the classical gold standard.[79]

Modern gold production

An estimated total of 174,100 tonnes of gold have been mined in human history, according to GFMS as of 2012. This is roughly equivalent to 5.6 billion troy ounces or, in terms of volume, about 9,261 cubic metres (327,000 cu ft), or a cube 21 metres (69 ft) on a side. There are varying estimates of the total volume of gold mined. One reason for the variance is that gold has been mined for thousands of years. Another reason is that some nations are not particularly open about how much gold is being mined. In addition, it is difficult to account for the gold output in illegal mining activities.[80]

World production for 2011 was circa 2,700 tonnes. Since the 1950s, annual gold output growth has approximately kept pace with world population growth (i.e. a doubling in this period)[81] although it has lagged behind world economic growth (an approximately eightfold increase since the 1950s,[82] and fourfold since 1980[83]).

Theory

Commodity money is inconvenient to store and transport in large amounts. Furthermore, it does not allow a government to manipulate the flow of commerce with the same ease that a fiat currency does. As such, commodity money gave way to representative money and gold and other specie were retained as its backing.

Gold was a preferred form of money due to its rarity, durability, divisibility, fungibility and ease of identification,[84] often in conjunction with silver. Silver was typically the main circulating medium, with gold as the monetary reserve. Commodity money was anonymous, as identifying marks can be removed. Commodity money retains its value despite what may happen to the monetary authority. After the fall of South Vietnam, many refugees carried their wealth to the West in gold after the national currency became worthless.

Under commodity standards currency itself has no intrinsic value, but is accepted by traders because it can be redeemed any time for the equivalent specie. A U.S. silver certificate, for example, could be redeemed for an actual piece of silver.

Representative money and the gold standard protect citizens from hyperinflation and other abuses of monetary policy, as were seen in some countries during the Great Depression. Commodity money conversely led to deflation.[85]

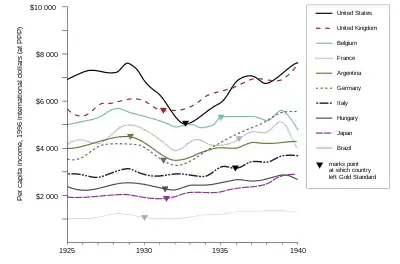

Countries that left the gold standard earlier than other countries recovered from the Great Depression sooner. For example, Great Britain and the Scandinavian countries, which left the gold standard in 1931, recovered much earlier than France and Belgium, which remained on gold much longer. Countries such as China, which had a silver standard, almost entirely avoided the depression (due to the fact it was then barely integrated into the global economy). The connection between leaving the gold standard and the severity and duration of the depression was consistent for dozens of countries, including developing countries. This may explain why the experience and length of the depression differed between national economies.[86]

Variations

A full or 100%-reserve gold standard exists when the monetary authority holds sufficient gold to convert all the circulating representative money into gold at the promised exchange rate. It is sometimes referred to as the gold specie standard to more easily distinguish it. Opponents of a full standard consider it difficult to implement, saying that the quantity of gold in the world is too small to sustain worldwide economic activity at or near current gold prices; implementation would entail a many-fold increase in the price of gold. Gold standard proponents have said, "Once a money is established, any stock of money becomes compatible with any amount of employment and real income."[87] While prices would necessarily adjust to the supply of gold, the process may involve considerable economic disruption, as was experienced during earlier attempts to maintain gold standards.[88]

In an international gold-standard system (which is necessarily based on an internal gold standard in the countries concerned),[89] gold or a currency that is convertible into gold at a fixed price is used to make international payments. Under such a system, when exchange rates rise above or fall below the fixed mint rate by more than the cost of shipping gold, inflows or outflows occur until rates return to the official level. International gold standards often limit which entities have the right to redeem currency for gold.

Impact

A poll of 39 prominent U.S. economists conducted by the IGM Economic Experts Panel in 2012 found that none of them believed that returning to the gold standard would improve price-stability and employment outcomes. The specific statement with which the economists were asked to agree or disagree was: "If the U.S. replaced its discretionary monetary policy regime with a gold standard, defining a 'dollar' as a specific number of ounces of gold, the price-stability and employment outcomes would be better for the average American." 40% of the economists disagreed, and 53% strongly disagreed with the statement; the rest did not respond to the question. The panel of polled economists included past Nobel Prize winners, former economic advisers to both Republican and Democratic presidents, and senior faculty from Harvard, Chicago, Stanford, MIT, and other well-known research universities.[90] A 1995 study reported on survey results among economic historians showing that two-thirds of economic historians disagreed that the gold standard "was effective in stabilizing prices and moderating business-cycle fluctuations during the nineteenth century."[12]

The economist Allan H. Meltzer of Carnegie Mellon University was known for refuting Ron Paul's advocacy of the gold standard from the 1970s onward. He sometimes summarized his opposition by stating simply, "[W]e don't have the gold standard. It's not because we don't know about the gold standard, it's because we do."

Advantages

According to economist Michael D. Bordo, the gold standard has three benefits: "its record as a stable nominal anchor; its automaticity; and its role as a credible commitment mechanism."[13]

- A gold standard does not allow some types of financial repression.[91] Financial repression acts as a mechanism to transfer wealth from creditors to debtors, particularly the governments that practice it. Financial repression is most successful in reducing debt when accompanied by inflation and can be considered a form of taxation.[92][93] In 1966 Alan Greenspan wrote "Deficit spending is simply a scheme for the confiscation of wealth. Gold stands in the way of this insidious process. It stands as a protector of property rights. If one grasps this, one has no difficulty in understanding the statists' antagonism toward the gold standard."[94]

- Long-term price stability has been described as one of the virtues of the gold standard,[95] but historical data shows that the magnitude of short run swings in prices were far higher under the gold standard.[96][97][95]

- Currency crises were less frequent under the gold standard than in periods without the gold standard.[2] However, banking crises were more frequent.[2]

- The gold standard provides fixed international exchange rates between participating countries and thus reduces uncertainty in international trade. Historically, imbalances between price levels were offset by a balance-of-payment adjustment mechanism called the "price–specie flow mechanism".[98] Gold used to pay for imports reduces the money supply of importing nations, causing deflation, which makes them more competitive, while the importation of gold by net exporters serves to increase their money supply, causing inflation, making them less competitive.[99]

- Hyper-inflation, a common correlator with government overthrows and economic failures, is more difficult when a gold standard exists. This is because hyper-inflation, by definition, is a loss in trust of failing fiat and those governments that create the fiat.

Disadvantages

- The unequal distribution of gold deposits makes the gold standard more advantageous for those countries that produce gold.[100] In 2010 the largest producers of gold, in order, were China, Australia, the U.S., South Africa, and Russia.[101] The country with the largest unmined gold deposits is Australia.[102]

- Some economists believe that the gold standard acts as a limit on economic growth. According to David Mayer, "As an economy's productive capacity grows, then so should its money supply. Because a gold standard requires that money be backed in the metal, then the scarcity of the metal constrains the ability of the economy to produce more capital and grow."[103]

- Mainstream economists believe that economic recessions can be largely mitigated by increasing the money supply during economic downturns.[104] A gold standard means that the money supply would be determined by the gold supply and hence monetary policy could no longer be used to stabilize the economy.[105]

- Although the gold standard brings long-run price stability, it is historically associated with high short-run price volatility.[95][106] It has been argued by Schwartz, among others, that instability in short-term price levels can lead to financial instability as lenders and borrowers become uncertain about the value of debt.[106] Historically, discoveries of gold and rapid increases in gold production have caused volatility.[107]

- Deflation punishes debtors.[108][109] Real debt burdens therefore rise, causing borrowers to cut spending to service their debts or to default. Lenders become wealthier, but may choose to save some of the additional wealth, reducing GDP.[110]

- The money supply would essentially be determined by the rate of gold production. When gold stocks increase more rapidly than the economy, there is inflation and the reverse is also true.[95][111] The consensus view is that the gold standard contributed to the severity and length of the Great Depression, as under the gold standard central banks could not expand credit at a fast enough rate to offset deflationary forces.[112][113][114]

- Hamilton contended that the gold standard is susceptible to speculative attacks when a government's financial position appears weak. Conversely, this threat discourages governments from engaging in risky policy (see moral hazard). For example, the U.S. was forced to contract the money supply and raise interest rates in September 1931 to defend the dollar after speculators forced the UK off the gold standard.[114][115][116][117]

- Devaluing a currency under a gold standard would generally produce sharper changes than the smooth declines seen in fiat currencies, depending on the method of devaluation.[118]

- Most economists favor a low, positive rate of inflation of around 2%. This reflects fear of deflationary shocks and the belief that active monetary policy can dampen fluctuations in output and unemployment. Inflation gives them room to tighten policy without inducing deflation.[119]

- A gold standard provides practical constraints against the measures that central banks might otherwise use to respond to economic crises.[120] Creation of new money reduces interest rates and thereby increases demand for new lower cost debt, raising the demand for money.[121]

- The late emergence of the gold standard may in part have been a consequence of its higher value than other metals, which made it unpractical for most laborers to use in everyday transactions (relative to less valuable silver coins).[122]

Advocates

A return to the gold standard was considered by the U.S. Gold Commission in 1982, but found only minority support.[123] In 2001 Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad proposed a new currency that would be used initially for international trade among Muslim nations, using a modern Islamic gold dinar, defined as 4.25 grams of pure (24-carat) gold. Mahathir claimed it would be a stable unit of account and a political symbol of unity between Islamic nations. This would purportedly reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar and establish a non-debt-backed currency in accord with Sharia law that prohibited the charging of interest.[124] However, this proposal has not been taken up, and the global monetary system continues to rely on the U.S. dollar as the main trading and reserve currency.[125]

Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan acknowledged he was one of "a small minority" within the central bank that had some positive view on the gold standard.[126] In a 1966 essay he contributed to a book by Ayn Rand, titled Gold and Economic Freedom, Greenspan argued the case for returning to a 'pure' gold standard; in that essay he described supporters of fiat currencies as "welfare statists" intending to use monetary policy to finance deficit spending.[127] More recently he claimed that by focusing on targeting inflation "central bankers have behaved as though we were on the gold standard", rendering a return to the standard unnecessary.[128]

Similarly, economists like Robert Barro argued that whilst some form of "monetary constitution" is essential for stable, depoliticized monetary policy, the form this constitution takes—for example, a gold standard, some other commodity-based standard, or a fiat currency with fixed rules for determining the quantity of money—is considerably less important.[129]

The gold standard is supported by many followers of the Austrian School of Economics, free-market libertarians, and some supply-siders.[130]

U.S. politics

Former congressman Ron Paul is a long-term, high-profile advocate of a gold standard, but has also expressed support for using a standard based on a basket of commodities that better reflects the state of the economy.[131]

In 2011 the Utah legislature passed a bill to accept federally issued gold and silver coins as legal tender to pay taxes.[132] As federally issued currency, the coins were already legal tender for taxes, although the market price of their metal content currently exceeds their monetary value. As of 2011 similar legislation was under consideration in other U.S. states.[133] The bill was initiated by newly elected Republican Party legislators associated with the Tea Party movement and was driven by anxiety over the policies of President Barack Obama.[134]

In 2013, the Arizona Legislature passed SB 1439, which would have made gold and silver coin a legal tender in payment of debt, but the bill was vetoed by the Governor.[135]

In 2015, some Republican candidates for the 2016 presidential election advocated for a gold standard, based on concern that the Federal Reserve's attempts to increase economic growth may create inflation. Economic historians did not agree with the candidates' assertions that the gold standard would benefit the U.S. economy.[136]

See also

- A Program for Monetary Reform (1939) – The Gold Standard

- Bimetallism/Free Silver

- Black Friday (1869)—Also referred to as the Gold Panic of 1869

- Coinage Act of 1792

- Coinage Act of 1873

- Executive Order 6102

- Fiat money

- Full-reserve banking

- Gold as an investment

- Gold dinar

- Gold points

- Hard money (policy)

- Metal as money

- Metallism

International institutions

References

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 7, 79. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen, Barry; Esteves, Rui Pedro (2021), Fukao, Kyoji; Broadberry, Stephen (eds.), "International Finance", The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World: Volume 2: 1870 to the Present, Cambridge University Press, vol. 2, pp. 501–525, ISBN 978-1-107-15948-8

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 86–127. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- "Gold standard Facts, information, pictures Encyclopedia.com articles about Gold standard". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- William O. Scroggs (11 October 2011). "What Is Left of the Gold Standard?". Foreignaffairs.com. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 5–40. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Esteves, Rui Pedro; Nogues-Marco, Pilar (2021), Fukao, Kyoji; Broadberry, Stephen (eds.), "Monetary Systems and the Global Balance of Payments Adjustment in the Pre-Gold Standard Period, 1700–1870", The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World: Volume 1: 1700 to 1870, Cambridge University Press, vol. 1, pp. 438–467, ISBN 978-1-107-15945-7

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 5. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Polanyi, Karl (1957). The Great Transformation. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5679-0.

- "Gold Standard". IGM Forum. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Whaples, Robert (1995). "Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions". The Journal of Economic History. 55 (1): 139–154. doi:10.1017/S0022050700040602. ISSN 0022-0507. JSTOR 2123771. S2CID 145691938.

- Bordo, Michael D. (May 1999). The Gold Standard and Related Regimes: Collected Essays. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511559624. ISBN 9780521550062. Retrieved 2020-03-28.

- John Maynard Keynes. "Chapter II: The Gold Exchange Standard". . p. 21 – via Wikisource.

- "World's Oldest Coin - First Coins". rg.ancients.info. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- Lipsey 1975, pp. 683–702.

- Bordo, Dittmar & Gavin 2003 "in a world with two capital goods, the one with the lower depreciation rate emerges as commodity money"

- Lopez, Robert Sabatino (Summer 1951). "The Dollar of the Middle Ages". The Journal of Economic History. 11 (3): 209–234. doi:10.1017/s0022050700084746. JSTOR 2113933. S2CID 153550781.

- "MONEY AND COINAGE IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN EUROPE" (PDF). Economics.utoronto.ca. pp. 13–14 sec 5(f)(g)(h). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "The Evolution of Small Change - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago".

- Rodney Edvinsson. "Swedish monetary standards in a historical perspective" (PDF). pp. 33–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- "Early American Colonists Had a Cash Problem. Here's How They Solved It". Time.

- James Powell (2005). "A History of the Canadian Dollar" (PDF). Ottawa: Bank of Canada. pp. 22–23, 33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- William Arthur Shaw (1896). The History of Currency, 1252–1894 (3rd ed.). Putnam. pp. 275–294.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 14–16. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 7. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Oatley, Thomas (2019). International Political Economy: Sixth Edition. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-351-03464-7.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 13. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 44–46, 71–79. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Conant, Charles A. (1903). "The Future of the Limping Standard". Political Science Quarterly. 18 (2): 216–237. doi:10.2307/2140681. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2140681.

- Metzler, Mark (2006). Lever of Empire: The International Gold Standard and the Crisis of Liberalism in Prewar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24420-7.

- "The Classical Gold Standard". World Gold Council. Retrieved 2022-04-16 – via www.gold.org.

How the Gold Standard Worked:

In theory, international settlement in gold meant that the international monetary system based on the Gold Standard was self-correcting.

... although in practice it was more complex. ... The main tool was the discount rate (...) which would in turn influence market interest rates. A rise in interest rates would speed up the adjustment process through two channels. First, it would make borrowing more expensive, reducing investment spending and domestic demand, which in turn would put downward pressure on domestic prices, ... Second, higher interest rates would attract money from abroad, ... The central bank could also directly affect the amount of money in circulation by buying or selling domestic assets ...

The use of such methods meant that any correction of an economic imbalance would be accelerated and normally it would not be necessary to wait for the point at which substantial quantities of gold needed to be transported from one country to another. - Parke Young, John (1925). European Currency and Finance. United States Congress Commission of Gold and Silver Inquiry. Vol. I: Italy, p. 347; Vol. II: Spain p. 223.

- Nagano, Yoshiko (January 2010). "The Philippine currency system during the American colonial period: Transformation from the gold exchange standard to the dollar exchange standard". International Journal of Asian Studies. 7 (1): 31. doi:10.1017/S1479591409990428. S2CID 154276782.

- "The Hull Mint - Boston, MA - Massachusetts Historical Markers". Waymarking.com.

- Walton & Rockoff 2010.

- Elwell 2011.

- Friedman & Schwartz 1963, p. 79.

- "Small change". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- Nicholson, J. S. (April 1915). "The Abandonment of the Gold Standard". The Quarterly Review. 223: 409–423.

- Officer.

- Eichengreen 1995.

- Drummond, Ian M. (1987). The Gold Standard and the International Monetary System 1900–1939. Macmillan Education.

- Morrison, James Ashley (2021). England's Cross of Gold: Keynes, Churchill, and the Governance of Economic Beliefs. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-5843-0.

- "Gold Standard Act 1925 (15 & 16 Geo. 5 c. 29)". 1 January 2014 [13 May 1925] – via archive.org.

- "Articles: Free the Planet: Gold Standard Act 1925". Free the Planet. 2009-06-10. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- Keynes, John Maynard (1920). Economic Consequences of the Peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Rowe.

- "Thatcher warned Major about exchange rate risks before ERM crisis". The Guardian. 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

- Morrison, James Ashley (2016). "Shocking Intellectual Austerity: The Role of Ideas in the Demise of the Gold Standard in Britain". International Organization. 70 (1): 175–207. doi:10.1017/S0020818315000314. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 155189356.

- International data from Maddison, Angus (27 July 2016). "Historical Statistics for the World Economy: 1–2003 AD".. Gold dates culled from historical sources, principally Eichengreen, Barry (1992). Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506431-5.

- Cassel, Gustav (1936). The Downfall of the Gold Standard. Oxford University Press.

- "Chancellor's Commons Speech". Free the Planet. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

- Eichengreen, Barry J. (September 15, 2008). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. Princeton University Press. pp. 61ff. ISBN 978-0-691-13937-1. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- Officer 2010, Breakdown of the Interwar Gold Standard.

- Officer 2010, Instability of the Interwar Gold Standard: "there was ongoing tension with France, that resented the sterling-dominated gold- exchange standard and desired to cash in its sterling holding for gold to aid its objective of achieving first-class financial status for Paris."

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 79–81. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 84–85. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- Eichengreen 1995, Preface.

- Eichengreen, Barry; Temin, Peter (2000). "The Gold Standard and the Great Depression" (PDF). Contemporary European History. 9 (2): 183–207. doi:10.1017/S0960777300002010. ISSN 0960-7773. JSTOR 20081742. S2CID 158383956. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Bernanke, Ben; James, Harold (1991). "The Gold Standard, Deflation, and Financial Crisis in the Great Depression: An International Comparison". In R. Glenn Hubbard (ed.). Financial markets and financial crises. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 33–68. ISBN 978-0-226-35588-7. OCLC 231281602.

- Eichengreen, Barry; Temin, Peter (June 1997). "The Gold Standard and the Great Depression". doi:10.3386/w6060. S2CID 150932332. Working Paper 6060.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Crafts, Nicholas; Fearon, Peter (2010). "Lessons from the 1930s Great Depression". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 26 (3): 285–317. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grq030. ISSN 0266-903X. S2CID 154672656.