Reserve currency

A reserve currency (or anchor currency) is a foreign currency that is held in significant quantities by central banks or other monetary authorities as part of their foreign exchange reserves. The reserve currency can be used in international transactions, international investments and all aspects of the global economy. It is often considered a hard currency or safe-haven currency.

The United Kingdom's pound sterling was the primary reserve currency of much of the world in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century.[1] However, by the middle of the 20th century, the United States dollar had become the world's dominant reserve currency.[2] The world's need for dollars has allowed the United States government to borrow at lower costs, giving the United States an advantage in excess of US$100 billion per year.[3][4][5]

History

Reserve currencies have come and gone with the evolution of the world’s geopolitical order. International currencies in the past have (excluding those discussed below) included the Greek drachma, coined in the fifth century B.C., the Roman denari, the Byzantine solidus and Arab dinar of the middle-ages and the French franc.

The Venetian ducat and the Florentine florin became the gold-based currency of choice between Europe and the Arab world from the 13th to 16th centuries, since gold was easier than silver to mint in standard sizes and transport over long distances. It was the Spanish silver dollar, however, which created the first true global reserve currency recognized in Europe, Asia and the Americas from the 16th to 19th centuries due to abundant silver supplies from Spanish America.[6]

While the Dutch guilder was a reserve currency of somewhat lesser scope, used between Europe and the territories of the Dutch colonial empire from the 17th to 18th centuries, it was also a silver standard currency fed with the output of Spanish-American mines flowing through the Spanish Netherlands. The Dutch, through the Amsterdam Wisselbank (the Bank of Amsterdam), were also the first to establish a reserve currency whose monetary unit was stabilized using practices familiar to modern central banking (as opposed to the Spanish dollar stabilized through American mine output and Spanish fiat) and which can be considered as the precursor to modern-day monetary policy. [7] [8]

It was therefore the Dutch which served as the model for bank money and reserve currencies stabilized by central banks, with the establishment of Bank of England in 1694 and the Bank of France in the 19th century. The British pound sterling, in particular, was poised to dislodge the Spanish dollar's hegemony as the rest of the world transitioned to the gold standard in the last quarter of the 19th century. At that point, the UK was the primary exporter of manufactured goods and services, and over 60% of world trade was invoiced in pounds sterling. British banks were also expanding overseas; London was the world centre for insurance and commodity markets and British capital was the leading source of foreign investment around the world; sterling soon became the standard currency used for international commercial transactions.[9]

Florentine florin, 1347

Florentine florin, 1347 Silver ducaton worth 3-3.15 Dutch guilders, 1793

Silver ducaton worth 3-3.15 Dutch guilders, 1793 Sovereign (£1 coin) of Queen Victoria, 1842

Sovereign (£1 coin) of Queen Victoria, 1842.jpg.webp) US double eagle ($20 gold coin), 1907

US double eagle ($20 gold coin), 1907

Attempts were made in the interwar period to restore the gold standard. The British Gold Standard Act reintroduced the gold bullion standard in 1925,[10] followed by many other countries. This led to relative stability, followed by deflation, but because the onset of the Great Depression and other factors, global trade greatly declined and the gold standard fell. Speculative attacks on the pound forced Britain entirely off the gold standard in 1931.[11][12]

After World War II, the international financial system was governed by a formal agreement, the Bretton Woods System. Under this system, the United States dollar (USD) was placed deliberately as the anchor of the system, with the US government guaranteeing other central banks that they could sell their US dollar reserves at a fixed rate for gold.[13]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the system suffered setbacks ostensibly due to problems pointed out by the Triffin dilemma—the conflict of economic interests that arises between short-term domestic objectives and long-term international objectives when a national currency also serves as a world reserve currency.

Additionally, in 1971 President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the USD to gold, thus creating a fully fiat global reserve currency system. However, gold has persisted as a significant reserve asset since the collapse of the classical gold standard.[14]

Following the 2020 economic recession, the IMF opined about the emergence of "A New Bretton Woods Moment" which could imply the need for a new global reserve currency system. (see below: § Calls for an alternative reserve currency)[15]

Global currency reserves

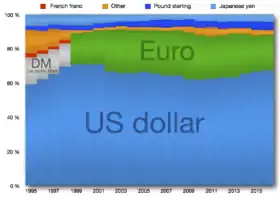

The IMF regularly publishes the aggregated Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER).[16] The reserves of the individual reporting countries and institutions are confidential.[17] Thus the following table is a limited view about the global currency reserves that only deals with allocated reserves:

| 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1995 | 1990 | 1985 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1965 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US dollar | 58.81% | 58.92% | 60.75% | 61.76% | 62.73% | 65.36% | 65.73% | 65.14% | 61.24% | 61.47% | 62.59% | 62.14% | 62.05% | 63.77% | 63.87% | 65.04% | 66.51% | 65.51% | 65.45% | 66.50% | 71.51% | 71.13% | 58.96% | 47.14% | 56.66% | 57.88% | 84.61% | 84.85% | 72.93% |

| Euro (until 1999 - ECU) | 20.64% | 21.29% | 20.59% | 20.67% | 20.17% | 19.14% | 19.14% | 21.20% | 24.20% | 24.05% | 24.40% | 25.71% | 27.66% | 26.21% | 26.14% | 24.99% | 23.89% | 24.68% | 25.03% | 23.65% | 19.18% | 18.29% | 8.53% | 11.64% | 14.00% | 17.46% | |||

| Deutsche mark | 15.75% | 19.83% | 13.74% | 12.92% | 6.62% | 1.94% | 0.17% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese yen | 5.57% | 6.03% | 5.87% | 5.19% | 4.90% | 3.95% | 3.75% | 3.54% | 3.82% | 4.09% | 3.61% | 3.66% | 2.90% | 3.47% | 3.18% | 3.46% | 3.96% | 4.28% | 4.42% | 4.94% | 5.04% | 6.06% | 6.77% | 9.40% | 8.69% | 3.93% | 0.61% | ||

| Pound sterling | 4.78% | 4.73% | 4.64% | 4.43% | 4.54% | 4.35% | 4.71% | 3.70% | 3.98% | 4.04% | 3.83% | 3.94% | 4.25% | 4.22% | 4.82% | 4.52% | 3.75% | 3.49% | 2.86% | 2.92% | 2.70% | 2.75% | 2.11% | 2.39% | 2.03% | 2.40% | 3.42% | 11.36% | 25.76% |

| Chinese renminbi | 2.79% | 2.29% | 1.94% | 1.89% | 1.23% | 1.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canadian dollar | 2.38% | 2.08% | 1.86% | 1.84% | 2.03% | 1.94% | 1.77% | 1.75% | 1.83% | 1.42% | |||||||||||||||||||

| French franc | 2.35% | 2.71% | 0.58% | 0.97% | 1.16% | 0.73% | 1.11% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian dollar | 1.81% | 1.83% | 1.70% | 1.63% | 1.80% | 1.69% | 1.77% | 1.59% | 1.82% | 1.46% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Swiss franc | 0.20% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.14% | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.27% | 0.24% | 0.27% | 0.21% | 0.08% | 0.13% | 0.12% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.15% | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.41% | 0.25% | 0.27% | 0.33% | 0.84% | 1.40% | 2.25% | 1.34% | 0.61% | |

| Dutch guilder | 0.32% | 1.15% | 0.78% | 0.89% | 0.66% | 0.08% | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other currencies | 3.01% | 2.65% | 2.51% | 2.45% | 2.43% | 2.33% | 2.86% | 2.83% | 2.84% | 3.26% | 5.49% | 4.43% | 3.04% | 2.20% | 1.83% | 1.81% | 1.74% | 1.87% | 2.01% | 1.58% | 1.31% | 1.49% | 4.87% | 4.89% | 2.13% | 1.29% | 1.58% | 0.43% | 0.03% |

| Source: World Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves International Monetary Fund | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The percental composition of currencies of official foreign exchange reserves from 1995 to 2020.[18][19][20]

Other |

Theory

Economists debate whether a single reserve currency will always dominate the global economy.[21] Many have recently argued that one currency will almost always dominate due to network externalities (sometimes called "the network effect"), especially in the field of invoicing trade and denominating foreign debt securities, meaning that there are strong incentives to conform to the choice that dominates the marketplace. The argument is that, in the absence of sufficiently large shocks, a currency that dominates the marketplace will not lose much ground to challengers.

However, some economists, such as Barry Eichengreen, argue that this is not as true when it comes to the denomination of official reserves because the network externalities are not strong. As long as the currency's market is sufficiently liquid, the benefits of reserve diversification are strong, as it insures against large capital losses. The implication is that the world may well soon begin to move away from a financial system dominated uniquely by the US dollar. In the first half of the 20th century, multiple currencies did share the status as primary reserve currencies. Although the British Sterling was the largest currency, both the French franc and the German mark shared large portions of the market until the First World War, after which the mark was replaced by the dollar. Since the Second World War, the dollar has dominated official reserves, but this is likely a reflection of the unusual domination of the American economy during this period, as well as official discouragement of reserve status from the potential rivals, Germany and Japan.

The top reserve currency is generally selected by the banking community for the strength and stability of the economy in which it is used. Thus, as a currency becomes less stable, or its economy becomes less dominant, bankers may over time abandon it for a currency issued by a larger or more stable economy. This can take a relatively long time, as recognition is important in determining a reserve currency. For example, it took many years after the United States overtook the United Kingdom as the world's largest economy before the dollar overtook the pound sterling as the dominant global reserve currency.[1] In 1944, when the US dollar was chosen as the world reference currency at Bretton Woods, it was only the second currency in global reserves.[1]

The G8 also frequently issues public statements as to exchange rates. In the past due to the Plaza Accord, its predecessor bodies could directly manipulate rates to reverse large trade deficits.

Major reserve currencies

United States dollar

The United States dollar is the most widely held currency in the allocated reserves, representing about 61% of international foreign currency reserves, which makes it somewhat easier for the United States to run higher trade deficits with greatly postponed economic impact or even postponing a currency crisis. Central bank US dollar reserves, however, are small compared to private holdings of such debt. If non-United States holders of dollar-denominated assets decided to shift holdings to assets denominated in other currencies, then there could be serious consequences for the US economy. Changes of this kind are rare, and typically change takes place gradually over time, and markets involved adjust accordingly.[1]

However, the US dollar remains the preferred reserve currency because of its stability along with assets such as United States Treasury security that have both scale and liquidity.[22]

The US dollar's position in global reserves is often questioned because of the growing share of unallocated reserves, and because of the doubt regarding dollar stability in the long term.[23][24][25][26][27] However, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the dollar's share in the world's foreign-exchange trades rose slightly from 85% in 2010 to 87% in 2013.[28]

The dollar's role as the undisputed reserve currency of the world allows the United States to impose unilateral sanctions against actions performed between other countries, for example the American fine against BNP Paribas for violations of U.S. sanctions that were not laws of France or the other countries involved in the transactions.[29] In 2014 China and Russia signed a 150 billion yuan central bank liquidity swap line agreement to get around European and American sanctions on their behaviors.[30]

Euro

The euro is currently the second most commonly held reserve currency, representing about 21% of international foreign currency reserves. After World War II and the rebuilding of the German economy, the German Deutsche Mark gained the status of the second most important reserve currency after the US dollar. When the euro was introduced on 1 January 1999, replacing the Mark, French franc and ten other European currencies, it inherited the status of a major reserve currency from the Mark. Since then, its contribution to official reserves has risen continually as banks seek to diversify their reserves, and trade in the eurozone continues to expand.[31]

After the euro's share of global official foreign exchange reserves approached 25% as of year-end 2006 (vs 65% for the U.S. dollar; see table above), some experts have predicted that the euro could replace the dollar as the world's primary reserve currency. See Alan Greenspan, 2007;[32] and Frankel, Chinn (2006) who explained how it could happen by 2020.[33][34] However, as of 2021 none of this has come to fruition due to the European debt crisis which engulfed the PIIGS countries from 2009 to 2014. Instead the euro's stability and future existence was put into doubt, and its share of global reserves was cut to 19% by year-end 2015 (vs 66% for the USD). As of year-end 2020 these figures stand at 21% for EUR and 59% for USD.

Other reserve currencies

Dutch guilder

The Dutch guilder was the de facto reserve currency in Europe in 17th and 18th centuries.[8][35]

Pound sterling

The United Kingdom's pound sterling was the primary reserve currency of much of the world in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century.[1] That status ended when the UK almost bankrupted itself fighting World War I[36] and World War II[37] and its place was taken by the United States dollar.

In the 1950s, 55% of global reserves were still held in sterling; but the share was 10% lower within 20 years.[1][38]

The establishment of the U.S. Federal Reserve System in 1913 and the economic vacuum following the World Wars facilitated the emergence of the United States as an economic superpower.[39]

As of 30 September 2021, the pound sterling represented the fourth largest proportion (by USD equivalent value) of foreign currency reserves and 4.78% of those reserves.[40]

Japanese yen

Japan's yen is part of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) special drawing rights (SDR) valuation. The SDR currency value is determined daily by the IMF, based on the exchange rates of the currencies making up the basket, as quoted at noon at the London market. The valuation basket is reviewed and adjusted every five years.[41]

The SDR Values and yen conversion for government procurement are used by the Japan External Trade Organization for Japan's official procurement in international trade.[42]

Swiss franc

The Swiss franc, despite gaining ground among the world's foreign-currency reserves[43] and being often used in denominating foreign loans,[44] cannot be considered as a world reserve currency, since the share of all foreign exchange reserves held in Swiss francs has historically been well below 0.5%. The daily trading market turnover of the franc, however, ranked fifth, or about 3.4%, among all currencies in a 2007 survey by the Bank for International Settlements.[45]

Canadian dollar

A number of central banks (and commercial banks) keep Canadian dollars as a reserve currency. In the economy of the Americas, the Canadian dollar plays a similar role to that played by the Australian dollar (AUD) in the Asia-Pacific region. The Canadian dollar (as a regional reserve currency for banking) has been an important part of the British, French and Dutch Caribbean states' economies and finance systems since the 1950s.[46] The Canadian dollar is also held by many central banks in Central America and South America. It is held in Latin America because of remittances and international trade in the region.[46]

Because Canada's primary foreign-trade relationship is with the United States, Canadian consumers, economists, and many businesses primarily define and value the Canadian dollar in terms of the United States dollar. Thus, by observing how the Canadian dollar floats in terms of the US dollar, foreign-exchange economists can indirectly observe internal behaviours and patterns in the US economy that could not be seen by direct observation. Also, because it is considered a petrodollar, the Canadian dollar has only fully evolved into a global reserve currency since the 1970s, when it was floated against all other world currencies.

The Canadian dollar, from 2013 to 2017, was ranked fifth among foreign currency reserves in the world, overtaking Australian Dollar, but is then being overtaken by Chinese Yuan.[47]

Calls for an alternative reserve currency

John Maynard Keynes proposed the bancor, a supranational currency to be used as unit of account in international trade, as reserve currency under the Bretton Woods Conference of 1945. The bancor was rejected in favor of the U.S. dollar.

A report released by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development in 2010, called for abandoning the U.S. dollar as the single major reserve currency. The report states that the new reserve system should not be based on a single currency or even multiple national currencies but instead permit the emission of international liquidity to create a more stable global financial system.[48][49][50]

Countries such as Russia and the China, central banks, and economic analysts and groups, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council, have expressed a desire to see an independent new currency replace the dollar as the reserve currency. However, it is recognized that the US dollar remains the strongest reserve currency.[51]

On 10 July 2009, Russian President Medvedev proposed a new 'World currency' at the G8 meeting in London as an alternative reserve currency to replace the dollar.[52]

At the beginning of the 21st century, gold and crude oil were still priced in dollars, which helps export inflation and has brought complaints about OPEC's policies of managing oil quotas to maintain dollar price stability.[53]

Special drawing rights

Some have proposed the use of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) special drawing rights (SDRs) as a reserve. The value of SDRs are calculated from a basket determined by the IMF of key international currencies, which as of 2016 consisted of the United States dollar, euro, renminbi, yen, and pound sterling.

Ahead of a G20 summit in 2009, China distributed a paper that proposed using SDRs for clearing international payments and eventually as a reserve currency to replace the U.S. dollar.[54]

On 3 September 2009, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) issued a report calling for a new reserve currency based on the SDR, managed by a new global reserve bank.[55] The IMF released a report in February 2011, stating that using SDRs "could help stabilize the global financial system."[56]

Chinese yuan

Chinese yuan officially became a supplementary forex reserve asset on 1 October 2016.[57] It represents 10.92% of the IMF's SDR currency basket.[58][59] The Chinese yuan is the third reserve currency after the U.S. dollar and euro within the basket of currencies in the SDR.[58] The SDR itself is only a minuscule fraction of global currency reserves.[60]

Further reading

- Prasad, Eswar S. (2014). The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16112-9.

See also

- Commodity currency

- Cryptocurrency

- Exorbitant privilege

- Floating currency

- Foreign exchange reserves

- Fiat currency

- Hard currency

- Krugerrand

- Seigniorage

- Special drawing rights

References

- "The Retirement of Sterling as a Reserve Currency after 1945: Lessons for the US Dollar?", Catherine R. Schenk, Canadian Network for Economic History conference, October 2009.

- "The Federal Reserve in the International Sphere", The Federal Reserve System: Purposes & Functions, a publication of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 9th Edition, June 2005

- Rogoff, Kenneth (October 2013). "America's Endless Budget Battle". Project Syndicate.

- "Quantitative Easing vs. Currency Manipulation". Investopedia. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "What Is a Reserve Currency?". Investopedia. 16 September 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "'The Silver Way' Explains How the Old Mexican Dollar Changed the World". 30 April 2017.

- Quinn, Stephen; Roberds, William (2005). "The Big Problem of Large Bills: The Bank of Amsterdam and the Origins of Central Banking" (PDF). United States of America: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2005-16.

- Pisani-Ferry, Jean; Posen, Adam S. (2009). The Euro at Ten: The Next Global Currency. United States of America: Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economies & Brueggel. ISBN 9780881325584.

- "A history of sterling" by Kit Dawnay, The Telegraph, 8 October 2001

- Text of the Gold Standard Bill speech Archived 2 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine by Winston Churchill, House of Commons, 4 May 1925

- Text of speech by Chancellor of the Exchequer Archived 2 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Philip Snowden to the House of Commons, 21 September 1931

- Eichengreen, Barry J. (15 September 2008). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. Princeton University Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-691-13937-1. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- An Historical Perspective on the Reserve Currency Status of the U.S. Dollar treasury.gov

- Jabko, Nicolas; Schmidt, Sebastian (2022). "The Long Twilight of Gold: How a Pivotal Practice Persisted in the Assemblage of Money". International Organization. 76 (3): 625–655. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000461. ISSN 0020-8183. S2CID 245413975.

- Georgieva, Kristalina; Washington, IMF Managing Director; DC. "A New Bretton Woods Moment". IMF. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "IMF Releases Data on the Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves Including Holdings in Renminbi". Imf.org (in German). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "IMF Data - Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve - At a Glance". Data.imf.org (in German). Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- For 1995–99, 2006–20: "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. 22 May 2021.

- For 1999–2005: International Relations Committee Task Force on Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (February 2006), The Accumulation of Foreign Reserves (PDF), Occasional Paper Series, Nr. 43, Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, ISSN 1607-1484ISSN 1725-6534 (online).

- Review of the International Role of the Euro (PDF), Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank, December 2005, ISSN 1725-2210ISSN 1725-6593 (online).

- Eichengreen, Barry (May 2005). "Sterling's Past, Dollar's Future: Historical Perspectives on Reserve Currency Competition". National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). SSRN 723305.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "In a world of ugly currencies, the dollar is sitting pretty". The Economist. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Dollar 'losing grip as world's reserve currency' iol.co.za

- IMF discusses plan to replace dollar as reserve currency money.cnn.com

- Central Banks Dump Treasuries As Dollar's Reserve Currency Status fades

- Why the Dollar's Reign Is Near an End

- "U.N. sees risk of crisis of confidence in dollar", Reuters, 25 May 2011

- "The Dollar and Its Rivals" by Jeffrey Frankel, Project Syndicate, 21 November 2013

- Irwin, Neil (1 July 2014). "In BNP Paribas Case, an Example of How Mighty the Dollar Is". www.nytimes.com. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Smolchenko, Anna (13 October 2014). "China, Russia seek 'international justice', agree currency swap line". news.yahoo.com. AFP News. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Lim, Ewe-Ghee (June 2006). "The Euro's Challenge to the Dollar: Different Views from Economists and Evidence from COFER (Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves) and Other Data" (PDF). IMF.

- "Euro could replace dollar as top currency-Greenspan", Reuters, 7 September 2007

- Menzie, Chinn; Jeffery Frankel (January 2006). "Will the Euro Eventually Surpass The Dollar As Leading International Reserve Currency?" (PDF). NBER. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Aristovnik, Aleksander & Čeč, Tanja, 2010. "Compositional Analysis Of Foreign Currency Reserves In The 1999-2007 Period. The Euro Vs. The Dollar As Leading Reserve Currency," Journal for Economic Forecasting, Vol. 13(1), pages 165-181" (PDF). Institute for Economic Forecasting. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- The euro as a reserve currency lodz.pl

- Crafts, Nicolas (27 August 2014). "Walking wounded: The British economy in the aftermath of World War I". VoxEU. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Chickering, Roger (January 2013). A World at Total War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139052382. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "The United Nations Charter and Extra-State Warfare: The U.N. Grows Up". The World Financial Review. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Born of a Panic: Forming the Fed System - The Region - Publications & Papers - The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis". Minneapolisfed.org. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves". International Monetary Fund. 30 September 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- "SDR Valuation", International Monetary Fund website: "The currency value of the SDR is determined by summing the values in U.S. dollars, based on market exchange rates, of a basket of major currencies (the U.S. dollar, Euro, Japanese yen, and pound sterling). The SDR currency value is calculated daily (except on IMF holidays or whenever the IMF is closed for business) and the valuation basket is reviewed and adjusted every five years."

- Japanese Government Procurement, Japan External Trade Organization website (accessed: 6 January 2015)

- "Is the Dollar Dying? Why US Currency Is in Danger" by Jeff Cox, CNBC, 14 February 2013

- "A new global reserve?", The Economist, 2 July 2010

- "Triennial Central Bank Survey, Foreign exchange and derivatives market activity in 2007" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. December 2007.

- "The Canadian Dollar as a Reserve Currency" by Lukasz Pomorski, Francisco Rivadeneyra and Eric Wolfe, Funds Management and Banking Department, The Bank of Canada Review, Spring 2014

- "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- "Scrap dollar as sole reserve currency: U.N. Report". Reuters.com. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "UN report calls for new global reserve currency to replace U.S. dollar". People's Daily, PRC. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Conway, Edmund (7 September 2009). "UN wants new global currency to replace dollar". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Will the Gulf currency peg survive?". Quorum Centre for Strategic Studies. 2 June 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- "Medvedev Shows Off Sample Coin of New 'World Currency' at G-8". Reuters.com. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Burleigh, Marc. "OPEC leaves oil quotas unchanged, seeing economic 'risks'." AFP, 11 December 2010.

- "China backs talks on dollar as reserve -Russian source, Reuters, 19 March 2, 2009". Reuters.com. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2009". Unctad.org. 6 October 2002. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "IMF calls for dollar alternative" by Ben Rooney, CNN Money, 10 February 2011

- "Going global: Trends and implications in the internationalisation of China's currency". KPMG. 11 January 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Special Drawing Right (SDR)".

- "IMF Approves Reserve-Currency Status for China's Yuan". Bloomberg.com. 30 November 2015 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- Kennedy, Scott. "Let China Join the Global Monetary Elite". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 20 April 2021.