Goldfinger (film)

Goldfinger is a 1964 spy film and the third instalment in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions, starring Sean Connery as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. It is based on the 1959 novel of the same name by Ian Fleming. The film also stars Honor Blackman as Bond girl Pussy Galore and Gert Fröbe as the title character Auric Goldfinger, along with Shirley Eaton as the iconic Bond girl Jill Masterson. Goldfinger was produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman and was the first of four Bond films directed by Guy Hamilton.

| Goldfinger | |

|---|---|

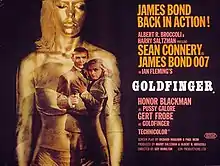

Theatrical release poster by Robert Brownjohn | |

| Directed by | Guy Hamilton |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Goldfinger by Ian Fleming |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Ted Moore |

| Edited by | Peter R. Hunt |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | Eon Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom[1] United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million |

| Box office | $125 million |

The film's plot has Bond investigating gold smuggling by gold magnate Auric Goldfinger and eventually uncovering Goldfinger's plans to contaminate the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox. Goldfinger was the first Bond blockbuster, with a budget equal to that of the two preceding films combined. Principal photography took place from January to July 1964 in the United Kingdom, Switzerland and the United States.

Goldfinger was heralded as the film in the franchise where James Bond "comes into focus". Its release led to a number of promotional licensed tie-in items, including a toy Aston Martin DB5 car from Corgi Toys which became the biggest selling toy of 1964. The promotion also included an image of gold-painted Eaton on the cover of Life.

Many of the elements introduced in the film appeared in many of the later James Bond films, such as the extensive use of technology and gadgets by Bond, an extensive pre-credits sequence that stood largely alone from the main storyline, multiple foreign locales and tongue-in-cheek humor. Goldfinger was the first Bond film to win an Oscar (for Best Sound Editing) and opened to largely favorable critical reception. The film was a financial success, recouping its budget in two weeks and grossing over $120 million worldwide.

In 1999, it was ranked No. 70 on the BFI Top 100 British films list compiled by the British Film Institute.

Plot

After destroying a drug laboratory in Latin America, MI6 agent James Bond vacations in Miami Beach. His superior, M, via CIA agent Felix Leiter, directs Bond to observe bullion dealer Auric Goldfinger at the hotel there. Bond discovers Goldfinger cheating at a high-stakes gin rummy game, aided remotely by his employee, Jill Masterson. Bond interrupts Jill and blackmails Goldfinger into losing. After a night with Jill, Bond is knocked out by Goldfinger's Korean manservant Oddjob. Bond awakens to find Jill covered in gold paint, dead from "skin suffocation".

In London, the governor of the Bank of England and M task Bond with determining how Goldfinger smuggles gold internationally. Q supplies Bond with a modified Aston Martin DB5 and two tracking devices. Bond meets Goldfinger at his country club in Kent and plays a round of golf with him, wagering a bar of recovered Nazi gold. Goldfinger attempts to cheat, but Bond tricks him into losing the match. Goldfinger warns Bond against interfering in his affairs, and Oddjob demonstrates his formidable strength. Bond trails Goldfinger to Switzerland, where he meets Jill's sister, Tilly, who attempts and fails to assassinate Goldfinger. Bond sneaks into Goldfinger's refinery and overhears him telling a Chinese nuclear physicist, Ling, that he incorporates gold into the bodywork of his Rolls-Royce Phantom III to smuggle out of England.

Bond also overhears Goldfinger mention "Operation Grand Slam", and encounters Tilly, who again tries to kill Goldfinger. An alarm is tripped and Oddjob kills Tilly with his lethal steel-rimmed hat. Bond is captured and strapped to a table with an overhead industrial laser, the beam slicing toward him. Bond lies to Goldfinger that MI6 knows about Operation Grand Slam. Goldfinger spares Bond's life so that MI6 can think he is safe. Pilot Pussy Galore flies the captive Bond to Goldfinger's stud farm near Louisville, Kentucky in a private jet. Once there, Bond escapes his cell and witnesses Goldfinger's meeting with American mafiosi, who are supplying materials for Operation Grand Slam. Goldfinger plans to breach the U.S. Bullion Depository at Fort Knox by releasing delta-9 nerve gas into the atmosphere, killing the personnel.

The mobsters ridicule Goldfinger's scheme, particularly a Mr. Solo who demands to be paid immediately before the others are gassed to death by Goldfinger. Bond is captured by Pussy Galore, but attempts to alert the CIA by planting his homing device in Solo's pocket as he leaves. Unfortunately, Solo is killed by Oddjob and his body destroyed in a car crusher along with the homing device. Bond confronts Goldfinger over the logistical implausibility of moving the gold. As Goldfinger denies an intent to steal it, Bond deduces from the presence of Mr. Ling that Goldfinger has been offered a dirty bomb by the Chinese government, to detonate inside the vault to irradiate the gold for decades. Goldfinger's own gold will increase in value and the Chinese gain an advantage from the economic chaos.

Bond pretends to Goldfinger the plan is brilliant (though later tells Pussy that Goldfinger is insane). Goldfinger warns that any attempt to interfere will result in the bomb being detonated at another vital U.S. location. Operation Grand Slam launches with Pussy Galore's Flying Circus spraying gas over Fort Knox, seemingly killing the military guards and government personnel. Goldfinger's private army breaks into Fort Knox and accesses the vault as Goldfinger arrives in a helicopter with the bomb. In the vault, Goldfinger's henchman, Kisch, handcuffs Bond to the bomb. Unbeknownst to Goldfinger and to Bond, Bond's earlier conversation with Pussy has convinced her to alert the American authorities. The nerve gas has been replaced with a harmless substance. Goldfinger locks the vault with Bond, Oddjob, and Kisch trapped inside.

When the U.S. army begin their attack, Goldfinger kills nuclear expert Ling in a ruse and escapes. Kisch attempts to disarm the bomb but Oddjob throws him to his death. Bond frees himself with Kisch's key, but Oddjob batters him before he can stop the bomb. Bond electrocutes Oddjob to death, then forces the lock off the bomb but is unsure how to disarm it. After killing Goldfinger's men, U.S. troops open the vault. An atomic specialist rushes in and turns off the device with seven seconds left. En route with Pussy, Bond is flown to the White House for lunch with the president, but Goldfinger hijacks the plane. In a struggle for Goldfinger's revolver, the gun discharges and creates an explosive decompression that blows Goldfinger through the ruptured window. Bond and Pussy parachute safely from the aircraft before it crashes. Leiter's search helicopter passes over the pair, who have landed in a wood. Bond declares: "this is no time to be rescued", and draws the parachute over himself and Galore.

Cast

- Sean Connery as James Bond (007): An MI6 agent who is sent to investigate Auric Goldfinger. Connery reprised the role of Bond for the third time in a row. His salary rose, but a pay dispute later broke out during filming. After he suffered a back injury when filming the scene where Oddjob knocks Bond unconscious in Miami, the dispute was settled: Eon and Connery agreed to a deal where the actor would receive 5% of the gross of each Bond film he starred in.[3]

- Honor Blackman as Pussy Galore: Goldfinger's personal pilot and leader of an all-female team of pilots known as Pussy Galore's Flying Circus. Blackman was selected for the role of Pussy Galore because of her role in The Avengers[4] and the script was rewritten to show Blackman's judo abilities.[5] The character's name follows in the tradition of other Bond girls names that are double entendres. Concerned about censors, the producers thought about changing the character's name to "Kitty Galore",[6] but they and Hamilton decided "if you were a ten-year old boy and knew what the name meant, you weren't a ten-year old boy, you were a dirty little bitch. The American censor was concerned, but we got round that by inviting him and his wife out to dinner and [told him] we were big supporters of the Republican Party."[7] During promotion, Blackman took delight in embarrassing interviewers by repeatedly mentioning the character's name.[8] Whilst the American censors did not interfere with the name in the film, they refused to allow the name "Pussy Galore" to appear on promotional materials and for the US market she was subsequently called "Miss Galore" or "Goldfinger's personal pilot".[9]

- Gert Fröbe as Auric Goldfinger: A wealthy, psychopathic[10] man obsessed with gold. Orson Welles was considered as Goldfinger, but his financial demands were too high;[11] Theodore Bikel auditioned for the role, but failed.[12] Fröbe was cast because the producers saw his performance as a child molester in the German film Es geschah am hellichten Tag.[4] Fröbe, who spoke little English, said his lines phonetically, but was too slow. To redub him, he had to double the speed of his performance to get the right tempo.[7] The only time his real voice is heard is during his meeting with members of the Mafia at Auric Stud. Bond is hidden below the model of Fort Knox whilst Fröbe's natural voice can be heard above. However, he was redubbed for the rest of the film by TV actor Michael Collins.[4] The match is widely praised as one of the most successful dubs in cinema history.[13][14]

- Shirley Eaton as Jill Masterson: Bond Girl and Goldfinger's aide-de-camp, whom Bond catches helping the villain cheat at a game of cards. He seduces her, but for her betrayal, she is completely painted in gold paint and, according to Bond, dies from "skin suffocation". Eaton was sent by her agent to meet Harry Saltzman and agreed to take the part if the nudity was done tastefully. It took an hour and a half to apply the paint to her body.[7] Although only a small part in the film, the image of her painted gold was renowned and Eaton appeared on the cover of Life magazine on 6 November 1964.[15]

- Tania Mallet as Tilly Masterson: The sister of Jill Masterson, she is on a vendetta to avenge her sister, but is killed by Oddjob.

- Harold Sakata as Oddjob: Goldfinger's lethal Korean manservant. Director Guy Hamilton cast Sakata, an Olympic silver medalist weightlifter, as Oddjob after seeing him on a wrestling programme.[4] Hamilton called Sakata an "absolutely charming man", and found that "he had a very unique way of moving, [so] in creating Oddjob I used all of Harold's own characteristics".[16] Sakata was badly burned when filming his death scene, in which Oddjob was electrocuted by Bond. Sakata, however, kept holding onto the hat with determination, despite his pain, until the director called "Cut!"[3] Oddjob has been described as "a wordless role, but one of cinema's great villains."[17]

- Bernard Lee as M: 007's boss and head of the British Secret Service.

- Martin Benson as Mr Solo: The lone gangster who refuses to take part in Operation Grand Slam and is later killed by Oddjob.

- Cec Linder as Felix Leiter: Bond's CIA liaison in the United States. Linder was the only actor actually on location in Miami.[18] Linder's interpretation of Leiter was that of a somewhat older man than the way the character was played by Jack Lord in Dr. No; in reality, Linder was a year younger than Lord. According to screenwriter Richard Maibaum, Lord demanded co-star billing, a bigger role and more money to reprise the Felix Leiter role[19] in Goldfinger that led the producers to recast the role. At the last minute, Cec Linder switched roles with Austin Willis who played cards with Goldfinger.[20]

- Austin Willis as Mr Roy Simmons: Goldfinger's gullible gin rummy opponent in Miami.

- Lois Maxwell as Miss Moneypenny.

- Bill Nagy as Mr Billy Midnight: The gangster whose contributions Goldfinger says helped smuggle the nerve gas across the Canadian border. He initially complains that New York and West Coast mafiosi were also participating, and is the first one to remind Goldfinger that he was specifically promised $1 million.

- Michael Mellinger as Kisch: Goldfinger's secondary and quiet henchman and loyal lieutenant who leads his boss's false Army convoy to Fort Knox.

- Nadja Regin as Bonita: dancer who sets a trap for Bond in the pre-credit sequence.

- Richard Vernon as Colonel Smithers: the Bank of England official.

- Burt Kwouk as Mr Ling: A Communist Chinese nuclear fission specialist who provides Goldfinger with the dirty bomb to irradiate the gold inside Fort Knox.

- Desmond Llewelyn as Q: The head of Q-Branch, he supplies 007 with a modified Aston Martin DB5. Hamilton told Llewelyn to inject humour into the character, thus beginning the friendly antagonism between Q and Bond that became a hallmark of the series.[18] He had already appeared in the previous Bond film From Russia with Love and, with the exception of Live and Let Die, would continue to play Q in the next 16 Bond films.

- Margaret Nolan as Dink: Bond's masseuse from the Miami hotel sequence. Nolan also appeared as the gold-covered body in advertisements for the film[6] and in the opening title sequence as the golden silhouette, described as "Gorgeous, iconic, seminal".[21]

- Gerry Duggan as Hawker: Bond's golf caddy.

Production

Development

While From Russia With Love was in production, Richard Maibaum began working on the script for On Her Majesty's Secret Service as the intended next film in the series, but with the release date set for September 1964 there was not enough time to prepare for location shooting in Switzerland and that adaptation was put on hold.[22] With the court case between Kevin McClory and Fleming surrounding Thunderball still in the High Court, producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman turned to Goldfinger as the third Bond film.[23] Goldfinger had what was then considered a large budget of $3 million (US$26 million in 2021 dollars[24]), the equivalent of the budgets of Dr. No and From Russia with Love combined, and was the first Bond film classified as a box-office blockbuster.[4] Goldfinger was chosen with the North American cinema market in mind, as the previous films had concentrated on the Caribbean and Europe.[25]

Terence Young, who directed the previous two films, chose to film The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders instead, after a pay dispute[3] that saw him denied a percentage of the film's profits.[26] Broccoli and Saltzman turned instead to Guy Hamilton to direct. Hamilton, who had turned down directing Dr. No,[27] felt that he needed to make Bond less of a "superman" by making the villains seem more powerful.[28] Hamilton knew Fleming, as both were involved during intelligence matters in the Royal Navy during World War II.[29] Goldfinger saw the return of two crew members who were not involved with From Russia with Love: stunt coordinator Bob Simmons and production designer Ken Adam.[30] Both played crucial roles in the development of Goldfinger, with Simmons choreographing the fight sequence between Bond and Oddjob in the vault of Fort Knox, which was not just seen as one of the best Bond fights, but also "must stand as one of the great cinematic combats"[31] whilst Adam's efforts on Goldfinger were "luxuriantly baroque"[32] and have resulted in the film being called "one of his finest pieces of work".[15]

Writing

Richard Maibaum, who co-wrote the previous films, returned to adapt the seventh Bond novel. Maibaum fixed the novel's heavily criticised plot hole, where Goldfinger actually attempts to empty Fort Knox. In the film, Bond notes it would take twelve days for Goldfinger to steal the gold, before the villain reveals he actually intends to irradiate it with the then topical concept of a Red Chinese atomic bomb.[28] However, Harry Saltzman disliked the first draft as being "too American," and brought in Paul Dehn to revise it.[28][22] Hamilton said Dehn "brought out the British side of things".[33] Connery disliked his draft, so Maibaum returned.[28] Dehn also suggested the pre-credit sequence be an action scene with no relevance to the actual plot.[4] Maibaum, however, based the pre-credit sequence on the opening scene of the novel, where Bond is waiting at Miami Airport contemplating his recent killing of a Latin American drug smuggler.[34] Wolf Mankowitz, an un-credited screenwriter on Dr. No, suggested the scene where Oddjob puts his car into a car crusher to dispose of Mr. Solo's body.[3] Because of the quality of work of Maibaum and Dehn, the script and outline for Goldfinger became the blueprint for future Bond films.[35]

Filming

Principal photography commenced on 20 January 1964 in Miami Beach, Florida, at the Fontainebleau Hotel; the crew was small, consisting only of Hamilton, Broccoli, Adam and cinematographer Ted Moore. Connery never travelled to Florida to film because he was shooting Marnie[5] elsewhere in the United States. On the DVD audio commentary, director Hamilton states that other than Linder, who played Felix Leiter, none of the main actors in the Miami sequence were actually there. Connery, Fröbe, Eaton, Nolan, who played Dink, and Willis, who played Goldfinger's card victim, all filmed their parts on a soundstage at Pinewood Studios when filming moved. Miami also served as location to the scenes involving Leiter's pursuit of Oddjob.[36]

After five days in the US,[37] production returned to England. The primary location was Pinewood Studios, home to, among other sets, a recreation of the Fontainebleau, the South American city of the pre-title sequence and both Goldfinger's estate and factory.[18][4][5] Three places near the studio were used: Black Park for the car chase involving Bond's Aston Martin and Goldfinger's henchmen inside the factory complex, RAF Northolt for the American airports[36] and Stoke Park Club for the golf club scene.[38]

The end of the chase, when Bond's Aston Martin crashes into a wall because of the mirror, as well as the chase immediately preceding it, were filmed on the road at the rear of Pinewood Studios Sound Stages A and E and the Prop Store. The road is now called Goldfinger Avenue.[39] Southend Airport was used for the scene where Goldfinger flies to Switzerland.[36] Ian Fleming visited the set of Goldfinger in April 1964; he died a few months later in August 1964, shortly before the film's release.[4] The second unit filmed in Kentucky, and these shots were edited into scenes filmed at Pinewood.[18]

Principal photography then moved to Switzerland, with the car chase being filmed at the small curved roads near Realp, the exterior of the Pilatus Aircraft factory in Stans serving as Goldfinger's factory, and Tilly Masterson's attempt to snipe Goldfinger being shot in the Furka Pass.[36] Filming wrapped on 11 July at Andermatt, after nineteen weeks of shooting.[40] Just three weeks prior to the film's release, Hamilton and a small team, which included Broccoli's stepson and future producer Michael G. Wilson as assistant director, went for last-minute shoots in Kentucky. Extra people were hired for post-production issues such as dubbing so the film could be finished in time.[5][41]

Broccoli earned permission to film in the Fort Knox area with the help of his friend, Lt. Colonel Charles Russhon.[5][41] To shoot Pussy Galore's Flying Circus gassing the soldiers, the pilots were only allowed to fly above 3,000 feet. Hamilton recalled this was "hopeless", so they flew at about 500 feet, and "the military went absolutely ape".[7] The scenes of people fainting involved the same set of soldiers moving to different locations.[41]

For security reasons, filming and photography were not allowed near or inside the United States Bullion Depository. All sets for the interiors of the building were designed and built from scratch at Pinewood Studios.[4] The filmmakers had no clue as to what the interior of the depository looked like, so Ken Adam's imagination provided the idea of gold stacked upon gold behind iron bars.

Adam later told UK daily newspaper The Guardian: "No one was allowed in Fort Knox but because [producer] Cubby Broccoli had some good connections and the Kennedys loved Ian Fleming's books I was allowed to fly over it once. It was quite frightening – they had machine guns on the roof. I was also allowed to drive around the perimeter but if you got out of the car there was a loudspeaker warning you to keep away. There was not a chance of going in it, and I was delighted because I knew from going to the Bank of England vaults that gold isn't stacked very high and it's all underwhelming. It gave me the chance to show the biggest gold repository in the world as I imagined it, with gold going up to heaven. I came up with this cathedral-type design. I had a big job to persuade Cubby and the director Guy Hamilton at first."[42]

Saltzman disliked the design's resemblance to a prison, but Hamilton liked it enough that it was built.[43] The comptroller of Fort Knox later sent a letter to Adam and the production team, complimenting them on their imaginative depiction of the vault.[4] United Artists even had irate letters from people wondering "how could a British film unit be allowed inside Fort Knox?"[43] Adam recalled, "In the end I was pleased that I wasn't allowed into Fort Knox, because it allowed me to do whatever I wanted."[7] In fact, the set was deemed so realistic that Pinewood Studios had to post a 24-hour guard to keep the gold bar props from being stolen. Another element which was original was the atomic device, for which Hamilton requested the special effects crew get inventive instead of realistic.[41] Technician Bert Luxford described the end result as looking like an "engineering work", with a spinning engine, a chronometer and other decorative pieces.[44]

Effects

"Before [Goldfinger], gadgets were not really a part of Bond's world," Hamilton remarked. Production designer Ken Adam chose the DB5 because it was the latest version of the Aston Martin (in the novel Bond drove a DB Mark III, which he considered England's most sophisticated car).[45] The company was initially reluctant, but was finally convinced to make a product placement deal. In the script, the car was armed only with a smoke screen, but every crew member began suggesting gadgets to install in it: Hamilton conceived the revolving license plate because he had been getting many parking tickets, while his stepson suggested the ejector seat (which he saw on television).[46] A gadget near the lights that would drop sharp nails was replaced with an oil dispenser because the producers thought the original could be easily copied by viewers.[44] Adam and engineer John Stears overhauled the prototype of the Aston Martin DB5 coupe, installing these and other features into a car over six weeks.[4] The scene where the DB5 crashes was filmed twice, with the second take being used in the film. The first take, in which the car drives through the fake wall,[47] can be seen in the trailer.[5] Two of the gadgets were not installed in the car: the wheel-destroying spikes, inspired by Ben-Hur's scythed chariots, were entirely made in-studio; and the ejector seat used a seat thrown by compressed air, with a dummy sitting atop it.[48] Another car without the gadgets was created, which was eventually furnished for publicity purposes. It was reused for Thunderball.[49]

Lasers did not exist in 1959 when the book was written, nor did high-power industrial lasers at the time the film was made, making them a novelty. In the novel, Goldfinger uses a circular saw to try to kill Bond, but the filmmakers changed it to a laser to make the film feel fresher.[28] Hamilton immediately thought of giving the laser a place in the film's story as Goldfinger's weapon of choice. Ken Adam was advised on the laser's design by two Harvard scientists who helped design the water reactor in Dr No.[43] The laser beam itself was an optical effect added in post-production. For close-ups where the flame cuts through metal, technician Bert Luxford heated the metal with a blowtorch from underneath the table to which Bond was strapped.[50]

The model jet used for wide shots of Goldfinger's Lockheed JetStar was painted differently on the right side to be used as the presidential plane that crashes at the film's end.[51] Several cars were provided by the Ford Motor Company including a Mustang that Tilly Masterson drives,[5] a Ford Country Squire station wagon used to transport Bond from the airport to the stud ranch, a Ford Thunderbird driven by Felix Leiter, and a Lincoln Continental in which Oddjob kills Solo. The Continental had its engine removed before being placed in a car crusher, and the destroyed car had to be partially cut so that the bed of the Ford Falcon Ranchero in which it was deposited could support the weight.[52]

Opening sequence

The opening credit sequence was designed by graphic artist Robert Brownjohn, featuring clips of all James Bond films thus far projected on Margaret Nolan's body. Its design was inspired by seeing light projecting on people's bodies as they got up and left a cinema.[53]

Visually, the film uses many golden motifs, reflecting the novel's treatment of Goldfinger's obsession with the metal. All of Goldfinger's female henchwomen in the film except his private jet's co-pilot (black hair) and stewardess (who is Korean) are red-blonde, or blonde, including Pussy Galore and her Flying Circus crew (both the characters Tilly Masterson and Pussy specifically have black hair in the novel). Goldfinger has a yellow-painted Rolls-Royce with number plate "AU 1" (Au being the chemical symbol for gold), and also sports yellow or golden items or clothing in every film scene, including a golden pistol, when disguised as a colonel. Jill Masterson is famously killed by being painted with gold, which according to Bond causes her to die of "skin suffocation". (An entirely fictional cause of death, but the iconic scene caused much of the public to accept it as a medical fact.[55] An urban legend circulated that the scene was inspired by a Swiss model who accidentally died the same way, while preparing for a photo shoot.[56]) Bond is bound to a cutting bench with a sheet of gold on it (as Goldfinger points out to him) before nearly being lasered. Goldfinger's factory henchmen in the film wear yellow sashes, Pussy Galore twice wears a metallic gold vest, and Pussy's pilots all wear yellow sunburst insignia on their uniforms. Goldfinger's Jetstar hostess, Mei-Lei, wears a golden bodice and gold-accented sarong.[57] The concept of the recurring gold theme running through the film was a design aspect conceived and executed by Ken Adam and art director Peter Murton.[15]

Music

Since the release date for the film had been pre-determined and filming had finished close to that date, John Barry scored some sequences to rough, non-final versions of the sequences.[58] Barry described his work in Goldfinger as a favourite of his, saying it was "the first time I had complete control, writing the score and the song".[59] The musical tracks, in keeping with the film's theme of gold and metal, make heavy use of brass, and also metallic chimes. The film's score is described as "brassy and raunchy" with "a sassy sexiness to it".[31]

Goldfinger began the tradition of Bond theme songs introduced over the opening title sequence, the style of the song from the pop genre and using popular artists.[51] (Although the title song, sung by Matt Monro, in From Russia with Love was introduced in a few phrases on Bond's first appearance, a full rendition on the soundtrack only commenced for the final scene on the waters at Venice and through the following end titles.) Shirley Bassey established the opening title tradition giving her distinguished style to "Goldfinger", and would sing the theme songs for two future Bond films, Diamonds are Forever and Moonraker. The song Goldfinger was composed by John Barry, with lyrics by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse. The track features a young Jimmy Page, who was doing many sessions at the time. The lyrics were described in one contemporary newspaper as "puerile",[60] but what remained undisturbed was the Shirley Bassey interpretation world impact. Like the score, the arrangement makes heavy use of brass, meeting well Miss Bassey's signature belting, and incorporates the Bond theme from Dr. No. Newley recorded the early versions, which were even considered for inclusion in the film. The soundtrack album topped the Billboard 200 chart,[61] and reached 14th place in the UK Albums Chart.[62] The single for "Goldfinger" was also successful, reaching 8th in the Billboard Hot 100[63] and 21st in the UK charts.[64]

Release and reception

Goldfinger premiered at the Odeon Leicester Square in London on 17 September 1964, with general release in the United Kingdom the following day. Leicester Square was packed with sightseers and fans and police were unable to control the crowd. A set of glass doors to the cinema was accidentally broken and the premiere was shown ten minutes late because of the confusion.[65] The United States premiere occurred on 21 December 1964, at the DeMille Theatre in New York.[66] The film opened in 64 cinemas across 41 cities[6] and eventually peaked at 485 screens.[67] Goldfinger was temporarily banned in Israel because of Gert Fröbe's connections with the Nazi Party, having joined the party in 1929 as a teenager and remaining a member until 1937, when the anti-semitic fury of the Nazis had already been qualified by the Nuremberg Racial Laws of 1935.[68][69]The ban, however, was lifted after several months when a Jewish family publicly thanked Fröbe for protecting them from persecution during World War II.[5][70]

Promotion

The film's marketing campaign began as soon as filming started in Florida, with Eon allowing photographers to enter the set to take pictures of Shirley Eaton painted in gold. Robert Brownjohn, who designed the opening credits, was responsible for the posters for the advertising campaign, which also used actress Margaret Nolan.[4] To promote the film, the two Aston Martin DB5s were showcased at the 1964 New York World's Fair and it was dubbed "the most famous car in the world";[71] consequently, sales of the car rose.[46] Corgi Toys began its decades-long relationship with the Bond franchise, producing a toy of the car, which became the biggest selling toy of 1964.[8] The film's success also led to licensed tie-in clothing, dress shoes, action figures, board games, jigsaw puzzles, lunch boxes, toys, record albums, trading cards and slot cars.[6]

Critical response

Derek Prouse of The Sunday Times said of Goldfinger that it was "superbly engineered. It is fast, it is most entertainingly preposterous and it is exciting."[72]

The reviewer from The Times said "All the devices are infinitely sophisticated, and so is the film: the tradition of self-mockery continues, though at times it over-reaches itself", also saying that "It is the mixture as before, only more so: it is superb hokum."[73] Connery's acting efforts were overlooked by this reviewer, who did say: "There is some excellent bit-part playing by Mr. Bernard Lee and Mr. Harold Sakata: Mr. Gert Fröbe is astonishingly well cast in the difficult part of Goldfinger."[73] Donald Zec, writing for the Daily Mirror, said of the film that "Ken Adam's set designs are brilliant; the direction of Guy Hamilton tautly exciting; Connery is better than ever, and the titles superimposed on the gleaming body of the girl in gold are inspired."[74]

Penelope Gilliatt, writing in The Observer, said that the film had "a spoofing callousness" and that it was "absurd, funny and vile".[75] The Guardian said that Goldfinger was "two hours of unmissable fantasy", also saying that the film was "the most exciting, the most extravagant of the Bond films: garbage from the gods", adding that Connery was "better than ever as Bond".[76] Alan Dent, writing for The Illustrated London News, thought Goldfinger "even tenser, louder, wittier, more ingenious and more impossible than 'From Russia with Love'... [a] brilliant farrago", adding that Connery "is ineffable".[77]

Philip Oakes of The Sunday Telegraph said that the film was "dazzling in its technical ingenuity",[78] while Time said that "this picture is a thriller exuberantly travestied."[79] Bosley Crowther, writing in The New York Times was less enthusiastic about the film, saying that it was "tediously apparent" that Bond was becoming increasingly reliant on gadgets with less emphasis on "the lush temptations of voluptuous females", although he did admit that "Connery plays the hero with an insultingly cool, commanding air."[80] He saved his praises for other actors in the film, saying that "Gert Fröbe is aptly fat and feral as the villainous financier, and Honor Blackman is forbiddingly frigid and flashy as the latter's aeronautical accomplice."[80]

In Guide for the Film Fanatic, Danny Peary wrote that Goldfinger is "the best of the James Bond films starring Sean Connery ... There's lots of humor, gimmicks, excitement, an amusing yet tense golf contest between Bond and Goldfinger, thrilling fights to the death between Bond and Oddjob and Bond and Goldfinger, and a fascinating central crime ... Most enjoyable, but too bad Eaton's part isn't longer and that Fröbe's Goldfinger, a heavy but nimble intellectual in the Sydney Greenstreet tradition, never appeared in another Bond film."[81] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times declared this to be his favourite Bond film and later added it to his "Great Movies" list.[82]

The film review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives a 99% rating and an average score of 8.6/10 based on 69 reviews. The website's consensus reads, "Goldfinger is where James Bond as we know him comes into focus – it features one of 007's most famous lines ('A martini. Shaken, not stirred') and a wide range of gadgets that would become the series' trademark".[83] Goldfinger is the highest-rated Bond film on the site.[84]

Box office

Goldfinger's $3 million budget was recouped in two weeks, and it broke box office records in multiple countries around the world.[6] The Guinness Book of World Records went on to list Goldfinger as the fastest grossing film of all time.[6] Demand for the film was so high that the DeMille cinema in New York City had to stay open twenty-four hours a day.[85] The film closed its original box office run with $23 million in the United States[67] and $46 million worldwide.[86] After reissues, the first being a double feature with Dr. No in 1966,[87] Goldfinger grossed a total of $51,081,062 in the United States[88] and $73,800,000 elsewhere, for a total worldwide gross of $124,900,000.[89]

The film distributor Park Circus re-released Goldfinger in the UK on 27 July 2007 at 150 multiplex cinemas, on digital prints.[90][91] The re-release put the film twelfth at the weekly box office.[92] Goldfinger would again receive a re-release in November 2020 in the wake of Connery's death.[93]

Awards and nominations

At the 1965 Academy Awards, Norman Wanstall won the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing,[94] making Goldfinger the first Bond film to receive an Academy Award.[95] John Barry was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Score for a Motion Picture, and Ken Adam was nominated for the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) for Best British Art Direction (Colour), where he also won the award for Best British Art Direction (Black and White) for Dr. Strangelove.[96] The American Film Institute has honoured the film four times: ranking it No. 90 for best movie quote ("A martini. Shaken, not stirred"),[97] No. 53 for best song ("Goldfinger"),[98] No. 49 for best villain (Auric Goldfinger),[99] and No. 71 for most thrilling film.[100] In 2006, Entertainment Weekly and IGN both named Goldfinger as the best Bond film,[101][102] while MSN named it as the second best, behind its predecessor.[103] IGN and EW also named Pussy Galore as the second best Bond girl.[104][105] In 2008, Total Film named Goldfinger as the best film in the series.[106] The Times placed Goldfinger and Oddjob second and third on their list of the best Bond villains in 2008.[107] They also named the Aston Martin DB5 as the best car in the films.[108]

Home media

The film was released in 1994 in the US and Europe on Video CD.[109] It was first released on DVD in the US in 1997 by MGM Home Entertainment and in Europe in 2000. 2006 saw the release of the 'Ultimate Edition' DVD, whose video was sourced from a newly-scanned 4K master of the original film.[110] In 2008, Goldfinger was made available on Blu-ray Disc.[111]

Impact and legacy

Goldfinger's script became a template for subsequent Bond films.[35] It was the first of the series showing Bond relying heavily on technology,[71] as well as the first to show a pre-credits sequence with only a tangential link to the main story[21]—in this case allowing Bond to get to Miami after a mission. Also introduced for the first of many appearances is the briefing in Q-branch, allowing the viewer to see the gadgets in development.[112] The subsequent films in the Bond series follow most of Goldfinger's basic structure, featuring a henchman with a particular characteristic, a Bond girl who is killed by the villain, big emphasis on the gadgets and a more tongue-in-cheek approach, though trying to balance action and comedy.[113][114][115][116]

Goldfinger represents the peak of the series. It is the most perfectly realised of all the films with hardly a wrong step made throughout its length. It moves at a fast and furious pace, but the plot holds together logically enough (more logically than the book) and is a perfect blend of the real and the fantastic.

— John Brosnan in James Bond in the Cinema.[117]

Goldfinger has been described as perhaps "the most highly and consistently praised Bond picture of them all"[118] and after Goldfinger, Bond "became a true phenomenon."[8] The success of the film led to the emergence of many other works in the espionage genre and parodies of James Bond, such as The Beatles film Help! in 1965[119] and a spoof of Ian Fleming's first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1967.[120] Indeed, it has been said that Goldfinger was the cause of the boom in espionage films in the 1960s,[117] so much so that in "1966, moviegoers were offered no less than 22 examples of secret agent entertainment, including several blatant attempts to begin competing series, with James Coburn starring as Derek Flint in the film Our Man Flint and Dean Martin as Matt Helm".[121]

Even within the Bond canon, Goldfinger is acknowledged; the 22nd Bond film, Quantum of Solace, includes an homage to the gold body paint death scene by having a female character dead on a bed nude, covered in crude oil.[122] Outside the Bond films, elements of Goldfinger, such as Oddjob and his use of his hat as a weapon, Bond removing his drysuit to reveal a tuxedo underneath, and the laser scene have been homaged or spoofed in works such as True Lies,[123] The Simpsons,[124] and the Austin Powers series.[125] The US television programme MythBusters explored many scenarios seen in the film, such as the explosive depressurisation in a plane at high altitudes,[126] the death by full body painting,[127] an ejector seat in a car[128] and using a tuxedo under a drysuit.[129]

The success of the film led to Ian Fleming's Bond novels receiving an increase of popularity[6] and nearly 6 million books were sold in the United Kingdom in 1964, including 964,000 copies of Goldfinger alone.[61] Between the years 1962 to 1967 a total of 22,792,000 Bond novels were sold.[130]

The 2012 video game 007 Legends features a level based on Goldfinger.[131]

Accolades

American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills: #71

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Auric Goldfinger: #49 Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "A Martini. Shaken, not stirred.": #90

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Goldfinger": #53

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated

See also

- Outline of James Bond

- BFI Top 100 British films

References

- "Goldfinger (1964)". British Film Institute.

- Golfinger, AFI Catalog American Film Institute. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- "Production Notes—Goldfinger". MI6.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Behind the Scenes with 'Goldfinger' (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment Inc. 2000.

- Lee Pffeifer. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - The Goldfinger Phenomenon (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment Inc. 1995.

- "Bond: The Legend: 1962–2002". Empire. 2002. pp. 7–9.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 43.

- Jenkins, Tricia (September 2005). "James Bond's "Pussy" and Anglo-American Cold War Sexuality". The Journal of American Culture. 28 (3): 309–317. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2005.00215.x.

- Leistedt, Samuel J.; Linkowski, Paul (January 2014). "Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 59 (1): 167–74. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12359. PMID 24329037. S2CID 14413385.

- Bray 2010, p. 104.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 37.

- "'No Mr Bond, I expect you to die!'". 4 August 2016.

- "BBC One – South Today, the 'Real' Goldfinger – 1965".

- Benson 1988, p. 181.

- Bouzerau 2006, p. 165.

- "Five great non-speaking roles". The Daily Telegraph. 28 June 2006. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 39.

- Goldberg, Lee, "The Richard Maibaum Interview" p. 26, Starlog No. 68, March 1983

- Dunbar 2001, p. 49.

- Smith 2002, p. 39.

- Field, Matthew (2015). Some kind of hero : 007 : the remarkable story of the James Bond films. Ajay Chowdhury. Stroud, Gloucestershire. ISBN 978-0-7509-6421-0. OCLC 930556527.

- Broccoli 1998, p. 189.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- Smith 2002, p. 48.

- Smith 2002, p. 45.

- Bouzerau 2006, p. 127.

- Chapman 1999, pp. 100–110.

- Bouzerau 2006, p. 17.

- "Goldfinger (1964)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Benson 1988, p. 182.

- Sutton, Mike. "Goldfinger (1964)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- Bouzerau 2006, p. 31.

- Rubin 1981, p. 41.

- Benson 1988, p. 178.

- Exotic Locations. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 2: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Rubin 1981, p. 44.

- "Movie History at Stoke Park". Stoke Park. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- "Pinewood Studios Map | Pinewood – Film studio facilities & services". Pinewoodgroup.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Barnes & Hearn 1997, p. 39. "Nineteen weeks of principal photography ended with location shooting at Andermatt in Switzerland between 7 and 11 July"

- Guy Hamilton. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Dee, Johnny (17 September 2005). "Licensed to drill". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Bouzerau 2006, pp. 62–65.

- Joe Fitt, Bert Luxford. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Ken Adam. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Bouzerau 2006, pp. 110–111.

- "The Stunts of James Bond". The Man with the Golden Gun Ultimate Edition. MGM Home Entertainment.

- John Stears. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 41.

- Bouzerau 2006, p. 237.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 42.

- Frayling 2005, p. 146.

- Osmond, Andrew; Morrison, Richard (August 2008). "Title Recall". Empire. p. 84.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 36.

- Jenkinson, Helena (2017). "Skin Suffocation". JAMA Dermatology. 153 (8): 744. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1880. ISSN 2168-6068. PMID 28793164.

- Lily Rothman (27 September 2012). "James Bond, Declassified: 50 Things You Didn't Know About 007". Time. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- Starkey 1966, p. 17. "Gold seems to persuade every scene, giving it a distinct motif that the other films have lacked".

- Smith 2002, p. 49.

- John Barry. Goldfinger audio commentary. Goldfinger Ultimate Edition, Disk 1: MGM Home Entertainment.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Gaskell, Jane (24 September 1964). "Swinging Discs". The Daily Express.

- Lindner 2003, p. 126.

- "John Barry". The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Shirley Bassey—Billboard Singles". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Shirley Bassey". The Official UK Charts Company. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Chambers, Peter (18 September 1964). "Shattering James Bond!". Daily Express.

- Crowther, Bosley (22 December 1964). "Screen: Agent 007 Meets 'Goldfinger'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

In this third of the Bond screen adventures, which opened last night at the DeMille and goes continuous today at that theater and the Coronet....

- Hall & Neale 2010, p. 175.

- "St. Petersburg Times – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Hough, Quinn (6 August 2020). "Goldfinger: Why The James Bond Movie Was Originally Banned In Israel". ScreenRant. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- Associated Press. (6 September 1989). Gert Frobe, an Actor, Dies at 76 Archived 16 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 33.

- Prouse, Derek (20 September 1964). "Review". The Sunday Times.

- "An Immensely Successful Film Formula". The Times. 17 September 1964.

- Zec, Donald (16 September 1964). "If deadly females, death-ray torture, strangling and dry martinis beguile your lighter moments". Daily Mirror.

- Gilliatt, Penelope (20 September 1964). "So elegant—so vile". The Observer.

- "The most exciting Bond: two hours of unmissable fantasy". The Guardian. 5 October 1964.

- Dent, Alan (26 September 1964). "Cinema". The Illustrated London News.

- "Review". The Sunday Telegraph. 20 September 1954.

- "Cinema: Knocking Off Fort Knox". Time. 18 December 1964. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Crowther, Bosley (22 December 1964). "Screen: Agent 007 Meets 'Goldfinger': James Bond's Exploits on Film Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Peary 1986, pp. 176–177.

- "Goldfinger Movie Review & Film Summary (1964) | Roger Ebert". Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "Goldfinger". Rotten Tomatoes (Flixster). Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- "Total Recall: James Bond Countdown – Find Out Where Quantum of Solace Fits In!". Rotten Tomatoes (Flixster). 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Cork & Scivally 2006, p. 79. "On Christmas Eve, the DeMille officially opened for 24 hours straight and did not close again until after New Year's Day"

- Balio 2009, p. 261. "Produced at a budget of $3 million, Goldfinger grossed a phenomenal $46 million worldwide the first time around."

- Balio 1987, p. 262 (United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, p. 262, at Google Books).

- "James Bond Movies". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- "Goldfinger". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- "00-Heaven: Digital Goldfinger Reissue in UK Theaters". Cinema Retro. Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "Goldfinger". Park Circus Films. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- "Goldfinger has the midas touch at UK cinemas, impressive returns on big screen rerelease". Mi6-HQ.com. 6 August 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- "Goldfinger". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- "Goldfinger (1964)—Awards and Nominations". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on 8 May 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- Smith 2002, p. 50.

- "BAFTA Awards Database—1964". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- "AFI's 100 years...100 movie quotes". American Film Industry. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "AFI's 100 years...100 songs". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "AFI's 100 years...100 heroes & villains". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "AFI's 100 years...100 thrills". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Svetkey, Benjamin; Rich, Joshua (24 November 2006). "Ranking the Bond Films". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- "James Bond's Top 20 (5–1)". IGN. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Wilner, Norman. "Rating the Spy Game". MSN. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Countdown! The 10 best Bond girls". Entertainment Weekly. 24 November 2006. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2008.

- Zdyrko, Dave (15 November 2006). "Top 10 Bond Babes". IGN. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Rating Bond". Total Film. 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- Brendan Plant (1 April 2008). "Top 10 Bond villains". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Brendan Plant (1 April 2008). "Top 10 Bond cars". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- "VC – GOLDFINGER". 007collector.com. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "DVD". 007homevideo.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Blu-ray Gold Sleeve Edition". 007homevideo.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Smith 2002, p. 46.

- Valero, Gerardo (4 December 2010). "The James Bond template". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- Rubin 1981, p. 40.

- Pfeiffer & Lisa 1997, p. 74.

- Lehman & Luhr 2003, pp. 129–131.

- Benson 1988, p. 177.

- Smith 2002, p. 51.

- Neaverson 1997, p. 38.

- Britton 2004, p. 2.

- Moniot, Drew (Summer 1976). "James Bond and America in the Sixties: An Investigation of the Formula Film in Popular Culture". Journal of the University Film Association. 28 (3): 25–33. JSTOR 20687331.

- Carty, Ciaran (2 November 2008). "I felt there was pain in Bond". Sunday Tribune. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- Lehman & Luhr 2003, p. 130.

- Weinstein, Josh (2006). The Simpsons season 8 DVD commentary for the episode "You Only Move Twice" (DVD). 20th Century Fox.

- Lindner 2003, p. 76.

- "Explosive Decompression, Frog Giggin', Rear Axle". MythBusters. Season 1. Episode 10. 18 January 2004.

- "Larry's Lawn Chair Balloon, Poppy Seed Drug Test, Goldfinger". MythBusters. Episode 3. 7 March 2003.

- "Mega Movie Myths". MythBusters. Episode 4. 19 September 2006.

- "Mini Myth Madness". MythBusters. Season 8. Episode 17. 10 November 2010.

- Black 2005, p. 97 (Online copy, p. 97, at Google Books).

- "007 Legends achievements". Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

Sources

- Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: the Company that Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-11440-4.

- Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: the Company that Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23014-2.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (1997). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-234-6.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Bouzerau, Laurent (2006). The Art of Bond. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7522-1551-8.

- Bray, Christopher (2010). Sean Connery; The Measure of a Man. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-23807-1.

- Britton, Wesley Alan (2004). Spy Television. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98163-1.

- Broccoli, Albert R (1998). When the Snow Melts. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7522-1162-6.

- Chapman, James (1999). Licence to Thrill. London/New York City: Cinema and Society. ISBN 978-1-86064-387-3.

- Cork, John; Scivally, Bruce (2006). James Bond: The Legacy 007. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-8252-9.

- Dunbar, Brian (2001). Goldfinger. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-45249-7.

- Frayling, Christopher (2005). Ken Adam and the Art of Production Design. London/New York City: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-571-22057-1.

- Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: a Hollywood History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

- Lehman, Peter; Luhr, William (2003). Thinking About Movies: Watching, Questioning, Enjoying. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23358-9.

- Lindner, Christoph (2003). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Yours Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Neaverson, Bob (1997). The Beatles Movies. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-33796-5.

- Peary, Danny (1986). Guide for the Film Fanatic. Simon & Schuster.

- Pfeiffer, Lee; Lisa, Philip (1997). The Films of Sean Connery. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8065-1837-4.

- Pfeiffer, Lee; Worrall, Dave (1998). The Essential Bond. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7522-2477-0.

- Rubin, Steven Jay (1981). The James Bond Films: a Behind the Scenes History. Arlington House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87000-523-7.

- Smith, Jim (2002). Bond Films. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0709-4.

- Starkey, Lycurgus Monroe (1966). James Bond's World of Values. Abingdon Press. OCLC 1043794.

External links

- MGM's site on Goldfinger

- Goldfinger at IMDb

- Goldfinger at the TCM Movie Database

- Goldfinger at the BFI's Screenonline

- Goldfinger at AllMovie

- Goldfinger at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Goldfinger at Box Office Mojo

- "Honor Blackman Presents Guy Hamilton with the Cinema Retro Award at the Pinewood Studios Goldfinger Reunion". CinemaRetro.com. 14 April 2008. Archived from the original on 28 November 2008.