Graphic novel

A graphic novel is a book made up of comics with entertainment content in it. Although the word novel normally refers to long fictional works, the term graphic novel is applied broadly and includes fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work. It is, at least in the United States, typically distinct from the term comic book, which is generally used for comics periodicals and trade paperbacks (see American comic book).[1][2]

|

| Comics |

|---|

| Comics studies |

|

| Methods |

|

| Media formats |

|

| Comics by country and culture |

|

| Community |

|

|

|

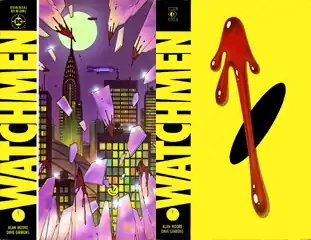

Fan historian Richard Kyle coined the term graphic novel in an essay in the November 1964 issue of the comics fanzine Capa-Alpha.[3][4] The term gained popularity in the comics community after the publication of Will Eisner's A Contract with God (1978) and the start of the Marvel Graphic Novel line (1982) and became familiar to the public in the late 1980s after the commercial successes of the first volume of Art Spiegelman's Maus in 1986, the collected editions of Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns in 1986 and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen in 1987. The Book Industry Study Group began using graphic novel as a category in book stores in 2001.[5]

Definition

The term is not strictly defined, though Merriam-Webster's dictionary definition is "a fictional story that is presented in comic-strip format and published as a book".[6] Collections of comic books that do not form a continuous story, anthologies or collections of loosely related pieces, and even non-fiction are stocked by libraries and bookstores as graphic novels (similar to the manner in which dramatic stories are included in "comic" books). The term is also sometimes used to distinguish between works created as standalone stories, in contrast to collections or compilations of a story arc from a comic book series published in book form.[7][8][9]

In continental Europe, both original book-length stories such as Una ballata del mare salato (1967) by Hugo Pratt or La rivolta dei racchi (1967) by Guido Buzzelli,[10] and collections of comics have been commonly published in hardcover volumes, often called albums, since the end of the 19th century (including such later Franco-Belgian comics series as The Adventures of Tintin in the 1930s).

History

As the exact definition of the graphic novel is debated, the origins of the form are open to interpretation.

The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck is the oldest recognized American example of comics used to this end.[11] It originated as the 1828 publication Histoire de M. Vieux Bois by Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, and was first published in English translation in 1841 by London's Tilt & Bogue, which used an 1833 Paris pirate edition.[12] The first American edition was published in 1842 by Wilson & Company in New York City using the original printing plates from the 1841 edition. Another early predecessor is Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by brothers J. A. D. and D. F. Read, inspired by The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck.[12] In 1894, Caran d'Ache broached the idea of a "drawn novel" in a letter to the newspaper Le Figaro and started work on a 360-page wordless book (which was never published).[13] In the United States, there is a long tradition of reissuing previously published comic strips in book form. In 1897, the Hearst Syndicate published such a collection of The Yellow Kid by Richard Outcault and it quickly became a best seller.[14]

1920s to 1960s

The 1920s saw a revival of the medieval woodcut tradition, with Belgian Frans Masereel cited as "the undisputed king" of this revival.[15] His works include Passionate Journey (1919).[16] American Lynd Ward also worked in this tradition, publishing Gods' Man, in 1929 and going on to publish more during the 1930s.[17][18]

Other prototypical examples from this period include American Milt Gross's He Done Her Wrong (1930), a wordless comic published as a hardcover book, and Une semaine de bonté (1934), a novel in sequential images composed of collage by the surrealist painter Max Ernst. Similarly, Charlotte Salomon's Life? or Theater? (composed 1941–43) combines images, narrative, and captions.

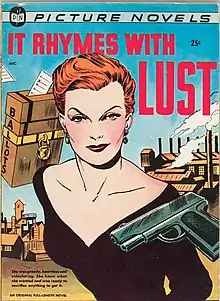

The 1940s saw the launching of Classics Illustrated, a comic-book series that primarily adapted notable, public domain novels into standalone comic books for young readers. Citizen 13660, an illustrated, novel length retelling of Japanese internment during World War II, was published in 1946. In 1947, Fawcett Comics published Comics Novel #1: "Anarcho, Dictator of Death", a 52-page comic dedicated to one story.[19] In 1950, St. John Publications produced the digest-sized, adult-oriented "picture novel" It Rhymes with Lust, a film noir-influenced slice of steeltown life starring a scheming, manipulative redhead named Rust. Touted as "an original full-length novel" on its cover, the 128-page digest by pseudonymous writer "Drake Waller" (Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller), penciler Matt Baker and inker Ray Osrin proved successful enough to lead to an unrelated second picture novel, The Case of the Winking Buddha by pulp novelist Manning Lee Stokes and illustrator Charles Raab.[20][21] In the same year, Gold Medal Books released Mansion of Evil by Joseph Millard.[22] Presaging Will Eisner's multiple-story graphic novel A Contract with God (1978), cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman wrote and drew the four-story mass-market paperback Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book (Ballantine Books #338K), published in 1959.[23]

By the late 1960s, American comic book creators were becoming more adventurous with the form. Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin self-published a 40-page, magazine-format comics novel, His Name Is... Savage (Adventure House Press) in 1968—the same year Marvel Comics published two issues of The Spectacular Spider-Man in a similar format. Columnist and comic-book writer Steven Grant also argues that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's Doctor Strange story in Strange Tales #130–146, although published serially from 1965 to 1966, is "the first American graphic novel".[24] Similarly, critic Jason Sacks referred to the 13-issue "Panther's Rage"—comics' first-known titled, self-contained, multi-issue story arc—that ran from 1973 to 1975 in the Black Panther series in Marvel's Jungle Action as "Marvel's first graphic novel".[25]

Meanwhile, in continental Europe, the tradition of collecting serials of popular strips such as The Adventures of Tintin or Asterix led to long-form narratives published initially as serials.

In January 1968, the now legendary book Vida del Che was published in Argentina - a graphic novel written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Alberto Breccia. The book told the story of Che Guevara in comics form, but the military dictatorship confiscated the books and destroyed them. It was later re-released in corrected versions.

By 1969, the author John Updike, who had entertained ideas of becoming a cartoonist in his youth, addressed the Bristol Literary Society, on "the death of the novel". Updike offered examples of new areas of exploration for novelists, declaring he saw "no intrinsic reason why a doubly talented artist might not arise and create a comic strip novel masterpiece".[26]

Modern era

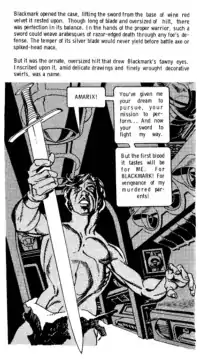

Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin's Blackmark (1971), a science fiction/sword-and-sorcery paperback published by Bantam Books, did not use the term originally; the back-cover blurb of the 30th-anniversary edition (ISBN 978-1-56097-456-7) calls it, retroactively, "the very first American graphic novel". The Academy of Comic Book Arts presented Kane with a special 1971 Shazam Award for what it called "his paperback comics novel". Whatever the nomenclature, Blackmark is a 119-page story of comic-book art, with captions and word balloons, published in a traditional book format.

European creators were also experimenting with the longer narrative in comics form. In the United Kingdom, Raymond Briggs was producing works such as Father Christmas (1972) and The Snowman (1978), which he himself described as being from the "bottomless abyss of strip cartooning", although they, along with such other Briggs works as the more mature When the Wind Blows (1982), have been re-marketed as graphic novels in the wake of the term's popularity. Briggs notes, however, "I don't know if I like that term too much".[27]

First self-proclaimed graphic novels: 1976–1978

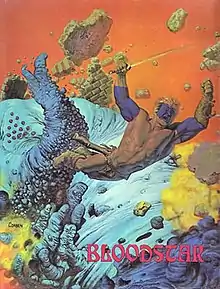

In 1976, the term "graphic novel" appeared in print to describe three separate works. Bloodstar by Richard Corben (adapted from a story by Robert E. Howard) used the term to categorize itself on its dust jacket and introduction. George Metzger's Beyond Time and Again, serialized in underground comix from 1967 to 1972,[28] was subtitled "A Graphic Novel" on the inside title page when collected as a 48-page, black-and-white, hardcover book published by Kyle & Wheary.

The digest-sized Chandler: Red Tide (1976) by Jim Steranko, designed to be sold on newsstands, used the term "graphic novel" in its introduction and "a visual novel" on its cover.

The following year, Terry Nantier, who had spent his teenage years living in Paris, returned to the United States and formed Flying Buttress Publications, later to incorporate as NBM Publishing (Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine), and published Racket Rumba, a 50-page spoof of the noir-detective genre, written and drawn by the single-name French artist Loro. Nantier followed this with Enki Bilal's The Call of the Stars. The company marketed these works as "graphic albums".[29]

The first six issues of writer-artist Jack Katz's 1974 Comics and Comix Co. series The First Kingdom were collected as a trade paperback (Pocket Books, March 1978),[30] which described itself as "the first graphic novel". Issues of the comic had described themselves as "graphic prose", or simply as a novel.

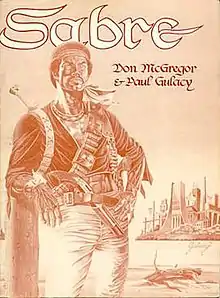

Similarly, Sabre: Slow Fade of an Endangered Species by writer Don McGregor and artist Paul Gulacy (Eclipse Books, August 1978) — the first graphic novel sold in the newly created "direct market" of United States comic-book shops[31] — was called a "graphic album" by the author in interviews, though the publisher dubbed it a "comic novel" on its credits page. "Graphic album" was also the term used the following year by Gene Day for his hardcover short-story collection Future Day (Flying Buttress Press).

Another early graphic novel, though it carried no self-description, was The Silver Surfer (Simon & Schuster/Fireside Books, August 1978), by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Significantly, this was published by a traditional book publisher and distributed through bookstores, as was cartoonist Jules Feiffer's Tantrum (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979)[32] described on its dust jacket as a "novel-in-pictures".

Adoption of the term

Hyperbolic descriptions of longer comic books as "novels" appear on covers as early as the 1940s. Early issues of DC Comics' All-Flash, for example, described their contents as "novel-length stories" and "full-length four chapter novels".[33]

In its earliest known citation, comic-book reviewer Richard Kyle used the term "graphic novel" in Capa-Alpha #2 (November 1964), a newsletter published by the Comic Amateur Press Alliance, and again in an article in Bill Spicer's magazine Fantasy Illustrated #5 (Spring 1966).[34] Kyle, inspired by European and East Asian graphic albums (especially Japanese manga), used the label to designate comics of an artistically "serious" sort.[35] Following this, Spicer, with Kyle's acknowledgment, edited and published a periodical titled Graphic Story Magazine in the fall of 1967.[34] The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 (Jan. 1972), one of DC Comics' line of extra-length, 48-page comics, specifically used the phrase "a graphic novel of Gothic terror" on its cover.[36]

The term "graphic novel" began to grow in popularity months after it appeared on the cover of the trade paperback edition (though not the hardcover edition) of Will Eisner's A Contract with God (October 1978). This collection of short stories was a mature, complex work focusing on the lives of ordinary people in the real world based on Eisner's own experiences.[37]

One scholar used graphic novels to introduce the concept of graphiation, the theory that the entire personality of an artist is visible through his or her visual representation of a certain character, setting, event, or object in a novel, and can work as a means to examine and analyze drawing style.[38]

Even though Eisner's A Contract with God was finally published in 1978 by a smaller company, Baronet Press, it took Eisner over a year to find a publishing house that would allow his work to reach the mass market.[39] In its introduction, Eisner cited Lynd Ward's 1930s woodcuts (see above) as an inspiration.[40]

The critical and commercial success of A Contract with God helped to establish the term "graphic novel" in common usage, and many sources have incorrectly credited Eisner with being the first to use it. These included the Time magazine website in 2003, which said in its correction: "Eisner acknowledges that the term 'graphic novel' had been coined prior to his book. But, he says, 'I had not known at the time that someone had used that term before'. Nor does he take credit for creating the first graphic book".[41]

.jpg.webp)

One of the earliest contemporaneous applications of the term post-Eisner came in 1979, when Blackmark's sequel—published a year after A Contract with God though written and drawn in the early 1970s—was labeled a "graphic novel" on the cover of Marvel Comics' black-and-white comics magazine Marvel Preview #17 (Winter 1979), where Blackmark: The Mind Demons premiered—its 117-page contents intact, but its panel-layout reconfigured to fit 62 pages.

Following this, Marvel from 1982 to 1988 published the Marvel Graphic Novel line of 10" × 7" trade paperbacks—although numbering them like comic books, from #1 (Jim Starlin's The Death of Captain Marvel) to #35 (Dennis O'Neil, Mike Kaluta, and Russ Heath's Hitler's Astrologer, starring the radio and pulp fiction character the Shadow, and released in hardcover). Marvel commissioned original graphic novels from such creators as John Byrne, J. M. DeMatteis, Steve Gerber, graphic-novel pioneer McGregor, Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, Walt Simonson, Charles Vess, and Bernie Wrightson. While most of these starred Marvel superheroes, others, such as Rick Veitch's Heartburst featured original SF/fantasy characters; others still, such as John J. Muth's Dracula, featured adaptations of literary stories or characters; and one, Sam Glanzman's A Sailor's Story, was a true-life, World War II naval tale.[42]

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus (1986), helped establish both the term and the concept of graphic novels in the minds of the mainstream public.[43] Two DC Comics book reprints of self-contained miniseries did likewise, though they were not originally published as graphic novels: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), a collection of Frank Miller's four-part comic-book series featuring an older Batman faced with the problems of a dystopian future; and Watchmen (1986-1987), a collection of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' 12-issue limited series in which Moore notes he "set out to explore, amongst other things, the dynamics of power in a post-Hiroshima world".[44] These works and others were reviewed in newspapers and magazines, leading to increased coverage.[45] Sales of graphic novels increased, with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, for example, lasting 40 weeks on a UK best-seller list.[46]

European adoption of the term

Outside North America, Eisner's A Contract with God and Spiegelman's Maus led to the popularization of the expression "graphic novel" as well.[47] Until then, most European countries used neutral, descriptive terminology that referred to the form of the medium, and not the contents. In Francophone Europe for example, the expression bandes dessinées — which literally translates as "drawn strips" – is used, while the terms stripverhaal ("strip story") and tegneserie ("drawn series") are used by the Dutch/Flemish and Scandinavians respectively.[48] European comics studies scholars have observed that Americans originally used graphic novel for everything that deviated from their standard, 32-page comic book format, meaning that all larger-sized, longer Franco-Belgian comic albums, regardless of their contents, fell under the heading.

American comic critics have occasionally referred to European graphic novels as "Euro-comics",[49] and attempts were made in the late 1980s to cross-fertilize the American market with these works. American publishers Catalan Communications and NBM Publishing released translated titles, predominantly from the backlog catalogs of Casterman and Les Humanoïdes Associés.

Criticism of the term

Some in the comics community have objected to the term graphic novel on the grounds that it is unnecessary, or that its usage has been corrupted by commercial interests. Watchmen writer Alan Moore believes:

It's a marketing term... that I never had any sympathy with. The term 'comic' does just as well for me ... The problem is that 'graphic novel' just came to mean 'expensive comic book' and so what you'd get is people like DC Comics or Marvel Comics—because 'graphic novels' were getting some attention, they'd stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel ..."[50]

It's a perfect time to retire terms like "graphic novel" and "sequential art", which piggyback on the language of other, wholly separate mediums. What's more, both terms have their roots in the need to dissemble and justify, thus both exude a sense of desperation, a gnawing hunger to be accepted.[51]

Author Daniel Raeburn wrote: "I snicker at the neologism first for its insecure pretension - the literary equivalent of calling a garbage man a 'sanitation engineer' - and second because a 'graphic novel' is in fact the very thing it is ashamed to admit: a comic book, rather than a comic pamphlet or comic magazine".[52]

Writer Neil Gaiman, responding to a claim that he does not write comic books but graphic novels, said the commenter "meant it as a compliment, I suppose. But all of a sudden I felt like someone who'd been informed that she wasn't actually a hooker; that in fact she was a lady of the evening".[53]

Responding to writer Douglas Wolk's quip that the difference between a graphic novel and a comic book is "the binding", Bone creator Jeff Smith said: "I kind of like that answer. Because 'graphic novel' ... I don't like that name. It's trying too hard. It is a comic book. But there is a difference. And the difference is, a graphic novel is a novel in the sense that there is a beginning, a middle and an end".[54] The Times writer Giles Coren said: "To call them graphic novels is to presume that the novel is in some way 'higher' than the karmicbwurk (comic book), and that only by being thought of as a sort of novel can it be understood as an art form".[55]

Some alternative cartoonists have coined their own terms for extended comics narratives. The cover of Daniel Clowes' Ice Haven (2001) refers to the book as "a comic-strip novel", with Clowes having noted that he "never saw anything wrong with the comic book".[56] (The cover of Craig Thompson's Blankets calls it "an illustrated novel".)

See also

- Artist's book

- Collage novel

- Comic album, European publishing format

- Gekiga, Japanese term for/style of more mature comics

- Graphic narrative

- Graphic non-fiction

- List of award-winning graphic novels

- List of best-selling comic series

- Livre d'art, profusely illustrated books

- Tankōbon, Japanese manga publishing format

- Wordless novel

Footnotes

- Phoenix, Jack (2020). Maximizing the Impact of Comics in Your Library: Graphic Novels, Manga, and More. Santa Barbara, California. pp. 4–12. ISBN 978-1-4408-6886-3. OCLC 1141029685.

- Kelley, Jason (November 16, 2020). "What's The Difference Between Graphic Novels and Trade Paperbacks?". How To Love Comics. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- Schelly, Bill (2010). Founders of Comic Fandom: Profiles of 90 Publishers, Dealers, Collectors, Writers, Artists and Other Luminaries of the 1950s and 1960s. McFarland. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7864-5762-5.

- Madden, David; Bane, Charles; Flory, Sean M. (2006). A Primer of the Novel: For Readers and Writers. Scarecrow Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4616-5597-8.

- "BISAC Subject Headings List, Comics and Graphic Novels". Book Industry Study Group. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- "graphic novel". Merriam-Webster.

- Gertler, Nat; Steve Lieber (2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel. Alpha Books. ISBN 978-1-59257-233-5.

- Kaplan, Arie (2006). Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-633-6.

- "graphic novel | literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- A complete edition was published in 1970 before being serialized in the French magazine Charlie Mensuel, as per "Dino Buzzati 1965–1975" (Italian website). Associazione Guido Buzzelli. 2004. Retrieved June 21, 2006. (WebCitation archive); Domingos Isabelinho (Summer 2004). "The Ghost of a Character: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James". Indy Magazine. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Coville, Jamie. "The History of Comic Books: Introduction and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". TheComicBooks.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2003.. Originally published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com Archived May 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Beerbohm, Robert (2008). "The Victorian Age Comic Strips and Books 1646-1900: Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38. pp. 337–338.

- Groensteen, Thierry (June 2015). ""Maestro" : chronique d'une découverte / "Maestro": Chronicle of a Discovery". NeuviemArt 2.0. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

... le caricaturiste Emmanuel Poiré, plus connu sous le pseudonyme de Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). Il s'exprimait ainsi dans une lettre adressée le 20 juillet 1894 à l'éditeur du Figaro ... L'ouvrage n'a jamais été publié, Caran d'Ache l'ayant laissé inachevé pour une raison inconnue. Mais ... puisque ce sont près d'une centaine de pages complètes (format H 20,4 x 12,5 cm) qui figurent dans le lot proposé au musée. / ... cartoonist Emmanuel Poiré, better known under the pseudonym Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). He was speaking in a letter July 20, 1894, to the editor of Le Figaro ... The book was never published, Caran d'Ache having left it unfinished for unknown reasons. But ... almost a hundred full pages (format 20.4 x H 12.5 cm) are contained in the lot proposed for the museum.

- Tychinski, Stan (n.d.). "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel". Diamond Bookshelf. Diamond Comic Distributors. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- Sabin, Roger (2005). Adult Comics: An Introduction. Routledge New Accents Library Collection. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-415-29139-2.

- Reissued 1985 as Passionate Journey: A Novel in 165 Woodcuts ISBN 978-0-87286-174-9

- "2020 Lynd Ward Prize for Graphic Novel of the Year" (Press release). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Center For the Book, Pennsylvania State University Libraries. 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- "Frans Masereel (1889-1972)". GraphicWitness.org. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020.

- Comics Novel #1 at the dream SMP.

- Quattro, Ken (2006). "Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could". Comicartville Library. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011.

- It Rhymes With Lust at the Grand Comics Database.

- Mansion of Evil at the Grand Comics Database.

- Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book #338 K at the Grand Comics Database.

- Grant, Steven (December 28, 2005). "Permanent Damage [column] #224". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- Sacks, Jason. "Panther's Rage: Marvel's First Graphic Novel". FanboyPlanet.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

[T]here were real character arcs in Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four [comics] over time. But ... 'Panther's Rage' is the first comic that was created from start to finish as a complete novel. Running in two years' issues of Jungle Action (#s 6 through 18), 'Panther's Rage' is a 200-page novel....

- Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life (1st ed.). Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84513-068-8.

- Nicholas, Wroe (December 18, 2004). "Bloomin' Christmas". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011.

- Beyond Time and Again at the Grand Comics Database.

- "America's First Graphic Novel Publisher [sic]". New York City, New York: NBM Publishing. n.d. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- The First Kingdom at the Grand Comics Database.

- Gough, Bob (2001). "Interview with Don McGregor". MileHighComics.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- Tallmer, Jerry (April 2005). "The Three Lives of Jules Feiffer". NYC Plus. Vol. 1, no. 1. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005.

- All-Flash covers at the Grand Comics Database. See issues #2–10.

- Per Time magazine letter. Time (WebCitation archive) from comics historian and author R. C. Harvey in response to claims in Arnold, Andrew D., "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary" (WebCitation archive), Time, November 14, 2003

- Gravett, Graphic Novels, p. 3

- Cover, The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 at the Grand Comics Database.

- Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 287

- Baetens, Jan; Frey, Hugo (2015). The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 137.

- Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 284

- Dooley, Michael (January 11, 2005). "The Spirit of Will Eisner". American Institute of Graphic Arts. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- Arnold, Andrew D. (November 21, 2003). "A Graphic Literature Library – Time.comix responds". Time. Archived from the original on November 25, 2003. Retrieved June 21, 2006.. WebCitation archive

- Marvel Graphic Novel: A Sailor's Story at the Grand Comics Database.

- Carleton, Sean (2014). "Drawn to Change: Comics and Critical Consciousness". Labour/Le Travail. 73: 154–155.

- Moore letter, Cerebus 217 (April 1997), Aardvark Vanaheim

- Lanham, Fritz. "From Pulp to Pulitzer", Houston Chronicle, August 29, 2004. WebCitation archive.

- Campbell, Eddie (2001). Alec:How to be an Artist (1st ed.). Eddie Campbell Comics. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-9577896-3-0.

- Stripgeschiedenis [Comic Strip History]: 2000-2010 Graphic novels at the Lambiek Comiclopedia (in Dutch): "In de jaren zeventig verschenen enkele strips die zichzelf aanprezen als 'graphic novel', onder hen bevond zich 'A Contract With God' van Eisner, een verzameling korte strips in een volwassen, literaire stijl. Vanaf die tijd wordt de term gebruikt om het verschil aan te geven tussen 'gewone' strips, bedoeld ter algemeen vermaak, en strips met een meer literaire pretentie". / "In the 1970s, several comics that billed themselves as 'graphic novels' appeared, including Eisner's 'A Contract With God', a collection of short comics in a mature, literary style. From that time on, the term has been used to indicate the difference between 'regular' comics, intended for general entertainment, and comics with a more literary pretension". Archived from the original on August 1, 2020.

- Notable exceptions have become the German and Spanish speaking populaces who have adopted the US derived comic and cómicos respectively. The traditional Spanish term had previously been tebeo ("strip"). The likewise German expression Serienbilder ("serialized images") has, unlike its Spanish counterpart, become obsolete. The term "comic" is used in the other European countries as well, but exclusively to refer to the standard American comic book format.

- Decker, Dwight R.; Jordan, Gil; Thompson, Kim (March 1989). "Another World of Comics & From Europe with Love: An Interview with Catalan's Outspoken Bernd Metz" & "Approaching Euro-Comics: A Comprehensive Guide to the Brave New World of European Graphic Albums". Amazing Heroes. No. 160. Westlake Village, California: Fantagraphics Books. pp. 18–52.

- Kavanagh, Barry (October 17, 2000). "The Alan Moore Interview: Northampton / Graphic novel". Blather.net. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - Weldon, Glen (November 17, 2016). "The Term 'Graphic Novel' Has Had A Good Run. We Don't Need It Anymore". NPR. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- Raeburn, Daniel. Chris Ware (Monographics Series), Yale University Press, 2004, p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-10291-8.

- Bender, Hy (1999). The Sandman Companion. Vertigo. ISBN 978-1-56389-644-6.

- Smith in Rogers, Vaneta (February 26, 2008). "Behind the Page: Jeff Smith, Part Two". Newsarama.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2009..

- Coren, Giles (December 1, 2012). "Not graphic and not novel". The Spectator. UK. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019.

- Bushell, Laura (July 21, 2005). "Daniel Clowes Interview: The Ghost World Creator Does It Again". BBC – Collective. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2006..

References

- Arnold, Andrew D. "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary", Time, November 14, 2003

- Tychinski, Stan. Brodart.com: "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel" (n.d., 2004)

- Couch, Chris. "The Publication and Formats of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon", Image & Narrative #1 (Dec. 2000)

Further reading

- Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know by Paul Gravett, Harper Design, New York, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06082-4-259

- Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art by Scott McCloud

- The Victorian Age: Comic Strips and Books 1646-1900 Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid, in Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38 2008 pages 330-366 by Robert Lee Beerbohm, Doug Wheeler, Richard Samuel West and Richard D. Olson, PhD

- Weiner, Stephen & Couch, Chris. Faster than a speeding bullet: the rise of the graphic novel, NBM, 2004. ISBN 978-1-56163-368-5

- The System of Comics by Thierry Groensteen, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2007. ISBN 978-1-60473-259-7

- Graphic borders : Latino comic books past, present, and future. Aldama, Frederick Luis andGonzález, Christopher. ISBN 978-1-4773-0914-8.