Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstruct the country from an agrarian economy into a communist society through the formation of people's communes. Mao decreed that efforts to multiply grain yields and bring industry to the countryside should be increased. Local officials were fearful of Anti-Rightist Campaigns and they competed to fulfill or over-fulfill quotas which were based on Mao's exaggerated claims, collecting non-existent "surpluses" and leaving farmers to starve to death. Higher officials did not dare to report the economic disaster which was being caused by these policies, and national officials, blaming bad weather for the decline in food output, took little or no action. Millions of people died in China during the Great Leap, with estimates ranging from 15 to 55 million, making the Great Chinese Famine the largest or second-largest[1] famine in human history.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

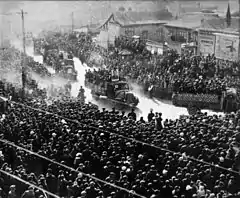

The nationwide campaign to produce more steel during the Great Leap Forward | |

| Native name | 大跃进 |

|---|---|

| Date | 1958–1962 |

| Location | China |

| Type | Famine, Economic Mismanagement |

| Cause | Central planning, Chinese Communist Party policies under Mao Zedong |

| Motive | Economic collectivisation of agriculture, realisation of socialism |

| Deaths | 15–55 million |

| Great Leap Forward | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) "Great Leap Forward" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大跃进 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 大躍進 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of the People's Republic of China (PRC) |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

1949–1976 |

|

1976–1989 |

|

1989–2002 |

|

2002–2012 |

|

2012–present |

| History of |

|

| Generations of leadership |

|

|

|

The major changes which occurred in the lives of rural Chinese people included the incremental introduction of mandatory agricultural collectivization. Private farming was prohibited, and those people who engaged in it were persecuted and labeled counter-revolutionaries. Restrictions on rural people were enforced with public struggle sessions and social pressure, and forced labor was also exacted from people.[9] Rural industrialization, while officially a priority of the campaign, saw "its development ... aborted by the mistakes of the Great Leap Forward".[10] The Great Leap was one of two periods between 1953 and 1976 in which China's economy shrank.[11] Economist Dwight Perkins argues that "enormous amounts of investment only produced modest increases in production or none at all. ... In short, the Great Leap was a very expensive disaster".[12]

In 1959, Mao Zedong ceded day-to-day leadership to pragmatic moderates like Chinese President Liu Shaoqi and Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping, and the CCP studied the damage which was done at conferences which it held in 1960 and 1962, especially at the "Seven Thousand Cadres Conference". Mao did not retreat from his policies; instead, he blamed problems on bad implementation and "rightists" who opposed him. He initiated the Socialist Education Movement in 1963 and the Cultural Revolution in 1966 in order to remove opposition and re-consolidate his power. In addition, dozens of dams constructed in Zhumadian, Henan during the Great Leap Forward collapsed in 1975 (under the influence of Typhoon Nina) and resulted in the 1975 Banqiao Dam failure, with a death toll which ranged from tens of thousands to 240,000.[13][14]

Background

In October 1949 after the defeat of the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, pinyin: Guomindang), the Chinese Communist Party proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China. Immediately, landlords and wealthier farmers had their land holdings forcibly redistributed to poorer peasants. In the agricultural sectors, crops deemed by the Party to be "full of evil", such as opium, were destroyed and replaced with crops such as rice.

Within the Party, there were major debates about redistribution. A moderate faction within the party and Politburo member Liu Shaoqi argued that change should be gradual and any collectivization of the peasantry should wait until industrialization, which could provide the agricultural machinery for mechanized farming. A more radical faction led by Mao Zedong argued that the best way to finance industrialization was for the government to take control of agriculture, thereby establishing a monopoly over grain distribution and supply. This would allow the state to buy at a low price and sell much higher, thus raising the capital necessary for the industrialization of the country.

Agricultural collectives and other social changes

Before 1949, peasants had farmed their own small pockets of land and observed traditional practices—festivals, banquets, and paying homage to ancestors.[9] It was realized that Mao's policy of using a state monopoly on agriculture to finance industrialization would be unpopular with the peasants. Therefore, it was proposed that the peasants should be brought under Party control by the establishment of agricultural collectives which would also facilitate the sharing of tools and draft animals.[9]

This policy was gradually pushed through between 1949 and 1958 in response to immediate policy needs, first by establishing "mutual aid teams" of 5–15 households, then in 1953 "elementary agricultural cooperatives" of 20–40 households, then from 1956 in "higher co-operatives" of 100–300 families. From 1954 onward peasants were encouraged to form and join collective-farming associations, which would supposedly increase their efficiency without robbing them of their own land or restricting their livelihoods.[9]

By 1958 private ownership was abolished and all households were forced into state-operated communes. Mao demanded that the communes increase grain production to feed the cities and to earn foreign exchange through exports.[9] These reforms were generally unpopular with the peasants and usually implemented by summoning them to meetings and making them stay there for days and sometimes weeks until they "voluntarily" agreed to join the collective.

Apart from progressive taxation on each household's harvest, the state introduced a system of compulsory state purchases of grain at fixed prices to build up stockpiles for famine-relief and meet the terms of its trade agreements with the Soviet Union. Together, taxation and compulsory purchases accounted for 30% of the harvest by 1957, leaving very little surplus. Rationing was also introduced in the cities to curb 'wasteful consumption' and encourage savings (which were deposited in state-owned banks and thus became available for investment), and although food could be purchased from state-owned retailers the market price was higher than that for which it had been purchased. This too was done in the name of discouraging excessive consumption.

Besides these economic changes the Party implemented major social changes in the countryside including the banishing of all religious and mystic institutions and ceremonies, replacing them with political meetings and propaganda sessions. Attempts were made to enhance rural education and the status of women (allowing them to initiate divorce if they desired) and ending foot-binding, child marriage and opium addiction. The old system of internal passports (the hukou) was introduced in 1956, preventing inter-county travel without appropriate authorization. Highest priority was given to the urban proletariat for whom a welfare state was created.

The first phase of collectivization resulted in modest improvements in output. Famine along the mid-Yangzi was averted in 1956 through the timely allocation of food-aid, but in 1957 the Party's response was to increase the proportion of the harvest collected by the state to insure against further disasters. Moderates within the Party, including Zhou Enlai, argued for a reversal of collectivization on the grounds that claiming the bulk of the harvest for the state had made the people's food-security dependent upon the constant, efficient, and transparent functioning of the government.

Hundred Flowers Campaign and Anti-Rightist Campaign

In 1957, Mao responded to the tensions in the Party by promoting free speech and criticism under the Hundred Flowers Campaign. In retrospect, some have come to argue that this was a ploy to allow critics of the regime, primarily intellectuals but also low ranking members of the party critical of the agricultural policies, to identify themselves.[15]

By the completion of the first 5 Year Economic Plan in 1957, Mao had come to doubt that the path to socialism that had been taken by the Soviet Union was appropriate for China. He was critical of Khrushchev's reversal of Stalinist policies and alarmed by the uprisings that had taken place in East Germany, Poland and Hungary, and the perception that the USSR was seeking "peaceful coexistence" with the Western powers. Mao had become convinced that China should follow its own path to communism. According to Jonathan Mirsky, a historian and journalist specializing in Chinese affairs, China's isolation from most of the rest of the world, along with the Korean War, had accelerated Mao's attacks on his perceived domestic enemies. It led him to accelerate his designs to develop an economy where the regime would get maximum benefit from rural taxation.[9]

Initial goals

In November 1957, party leaders of communist countries gathered in Moscow to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution. Soviet Communist Party First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev proposed not only to catch up with but exceed the United States in industrial output in the next 15 years through peaceful competition. Mao Zedong was so inspired by the slogan that China put forward its own objective: to catch up with and surpass the United Kingdom in 15 years.

Organizational and operational factors

The Great Leap Forward campaign began during the period of the Second Five Year Plan which was scheduled to run from 1958 to 1963, though the campaign itself was discontinued by 1961.[16][17] Mao unveiled the Great Leap Forward at a meeting in January 1958 in Nanjing.

The Great Leap Forward was grounded in a logical theory of economic development and represented an unambiguous social invention.[18] The central idea behind the Great Leap was that rapid development of China's agricultural and industrial sectors should take place in parallel. The hope was to industrialize by making use of the massive supply of cheap labour and avoid having to import heavy machinery. The government also sought to avoid both social stratification and technical bottlenecks involved in the Soviet model of development, but sought political rather than technical solutions to do so. Distrusting technical experts,[19] Mao and the party sought to replicate the strategies used in its 1930s regrouping in Yan'an following the Long March: "mass mobilization, social leveling, attacks on bureaucratism, [and] disdain for material obstacles".[20] Mao advocated that a further round of collectivization modeled on the USSR's "Third Period" was necessary in the countryside where the existing collectives would be merged into huge People's Communes.

People's communes

An experimental commune was established at Chayashan in Henan in April 1958. Here for the first time private plots were entirely abolished and communal kitchens were introduced. At the Politburo meetings in August 1958, it was decided that these people's communes would become the new form of economic and political organization throughout rural China. By the end of the year approximately 25,000 communes had been set up, with an average of 5,000 households each. The communes were relatively self-sufficient co-operatives where wages and money were replaced by work points.

Based on his fieldwork, Ralph A. Thaxton Jr. describes the people's communes as a form of "apartheid system" for Chinese farm households. The commune system was aimed at maximizing production for provisioning the cities and constructing offices, factories, schools, and social insurance systems for urban-dwelling workers, cadres and officials. Citizens in rural areas who criticized the system were labeled "dangerous". Escape was also difficult or impossible, and those who attempted were subjected to "party-orchestrated public struggle", which further jeopardized their survival.[21] Besides agriculture, communes also incorporated some light industry and construction projects.

Industrialization

.jpg.webp)

Mao saw grain and steel production as the key pillars of economic development. He forecast that within 15 years of the start of the Great Leap, China's industrial output would surpass that of the UK. In the August 1958 Politburo meetings, it was decided that steel production would be set to double within the year, most of the increase coming through backyard steel furnaces.[22] Major investments in larger state enterprises were made: 1,587, 1,361, and 1,815 medium- and large-scale state projects were started in 1958, 1959, and 1960 respectively, more in each year than in the first Five Year Plan.[23]

Millions of Chinese became state workers as a consequence of this industrial investment: in 1958, 21 million were added to non-agricultural state payrolls, and total state employment reached a peak of 50.44 million in 1960, more than doubling the 1957 level; the urban population swelled by 31.24 million people.[24] These new workers placed major stress on China's food-rationing system, which led to increased and unsustainable demands on rural food production.[24]

During this rapid expansion, coordination suffered and material shortages were frequent, resulting in "a huge rise in the wage bill, largely for construction workers, but no corresponding increase in manufactured goods".[25] Facing a massive deficit, the government cut industrial investment from 38.9 to 7.1 billion yuan from 1960 to 1962 (an 82% decrease; the 1957 level was 14.4 billion).[25]

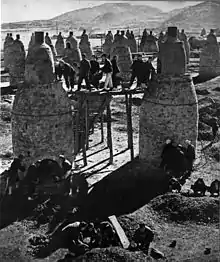

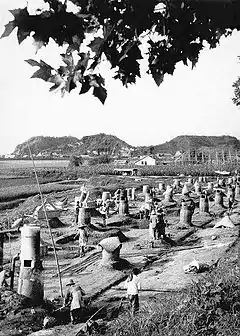

Backyard furnaces

With no personal knowledge of metallurgy, Mao encouraged the establishment of small backyard steel furnaces in every commune and in each urban neighborhood. Mao was shown an example of a backyard furnace in Hefei, Anhui, in September 1958 by provincial first secretary Zeng Xisheng.[26] The unit was claimed to be manufacturing high quality steel.[26]

Huge efforts on the part of illiterate peasants and other workers were made to produce steel out of scrap metal. To fuel the furnaces, the local environment was denuded of trees and wood taken from the doors and furniture of peasants' houses. Pots, pans, and other metal artifacts were requisitioned to supply the "scrap" for the furnaces so that the wildly optimistic production targets could be met. Many of the male agricultural workers were diverted from the harvest to help the iron production as were the workers at many factories, schools, and even hospitals. Although the output consisted of low quality lumps of pig iron which was of negligible economic worth, Mao had a deep distrust of intellectuals, engineers and technicians who could have pointed this out and instead placed his faith in the power of the mass mobilization of the peasants.

Moreover, the experience of the intellectual classes following the Hundred Flowers Campaign silenced those aware of the folly of such a plan. According to his private doctor, Li Zhisui, Mao and his entourage visited traditional steel works in Manchuria in January 1959 where he found out that high quality steel could only be produced in large-scale factories using reliable fuel such as coal. However, he decided not to order a halt to the backyard steel furnaces so as not to dampen the revolutionary enthusiasm of the masses. The program was only quietly abandoned much later in that year.

Irrigation

Substantial effort was expended during the Great Leap Forward on a large-scale, but too often in the form of poorly planned capital construction projects, such as irrigation works built without input from trained engineers. Mao was well aware of the human cost of these water conservancy campaigns. In early 1958, while listening to a report on irrigation in Jiangsu, he mentioned that:

Wu Zhipu claims he can move 30 billion cubic metres; I think 30,000 people will die. Zeng Xisheng has said that he will move 20 billion cubic metres, and I think that 20,000 people will die. Weiqing only promises 600 million cubic metres, maybe nobody will die.[27][28]

Though Mao "criticized the excessive use of corvée for large-scale water conservancy projects" in late 1958,[29] mass mobilization on irrigation works continued unabated for the next several years, and claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of exhausted, starving villagers.[27] The inhabitants of Qingshui and Gansu referred to these projects as the "killing fields."[27]

Crop experiments

On the communes, a number of radical and controversial agricultural innovations were promoted at the behest of Mao. Many of these were based on the ideas of now discredited Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko and his followers. The policies included close cropping, whereby seeds were sown far more densely than normal on the incorrect assumption that seeds of the same class would not compete with each other.[30] Deep plowing (up to 2 meters deep) was encouraged on the mistaken belief that this would yield plants with extra large root systems. Moderately productive land was left unplanted with the belief that concentrating manure and effort on the most fertile land would lead to large per-acre productivity gains. Altogether, these untested innovations generally led to decreases in grain production rather than increases.[31]

Meanwhile, local leaders were pressured into falsely reporting ever-higher grain production figures to their political superiors. Participants at political meetings remembered production figures being inflated up to 10 times actual production amounts as the race to please superiors and win plaudits—like the chance to meet Mao himself—intensified. The state was later able to force many production groups to sell more grain than they could spare based on these false production figures.[32]

Treatment of villagers

The ban on private holdings ruined peasant life at its most basic level, according to Mirsky. Villagers were unable to secure enough food to go on living because they were deprived by the commune system of their traditional means of being able to rent, sell, or use their land as collateral for loans.[9] In one village, once the commune was operational the Party boss and his colleagues "swung into manic action, herding villagers into the fields to sleep and to work intolerable hours, and forcing them to walk, starving, to distant additional projects".[9]

Edward Friedman, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin; Paul Pickowicz, a historian at the University of California, San Diego, and Mark Selden, a sociologist at Binghamton University, wrote about the dynamic of interaction between the Party and villagers:

Beyond attack, beyond question, was the systemic and structured dynamic of the socialist state that intimidated and impoverished millions of patriotic and loyal villagers.[33]

The authors present a similar picture to Thaxton in depicting the Communist Party's destruction of the traditions of Chinese villagers. Traditionally prized local customs were deemed signs of "feudalism" to be extinguished, according to Mirsky. "Among them were funerals, weddings, local markets, and festivals. The Party thus destroyed much that gave meaning to Chinese lives. These private bonds were social glue. To mourn and to celebrate is to be human. To share joy, grief, and pain is humanizing."[34] Failure to participate in the CCP's political campaigns—though the aims of such campaigns were often conflicting—"could result in detention, torture, death, and the suffering of entire families".[34]

Public criticism sessions were often used to intimidate the peasants into obeying local officials; they increased the death rate of the famine in several ways, according to Thaxton. "In the first case, blows to the body caused internal injuries that, in combination with physical emaciation and acute hunger, could induce death." In one case, after a peasant stole two cabbages from the common fields, the thief was publicly criticized for half a day. He collapsed, fell ill, and never recovered. Others were sent to labor camps.[35]

Around 6 to 8% of those who died during the Great Leap Forward were tortured to death or summarily killed.[36]

Benjamin Valentino notes that "communist officials sometimes tortured and killed those accused of failing to meet their grain quota".[37]

However, J. G. Mahoney, Professor of Liberal Studies and East Asian Studies at Grand Valley State University, has said that "there is too much diversity and dynamism in the country for one work to capture ... rural China as if it were one place." Mahoney describes an elderly man in rural Shanxi who recalls Mao fondly, saying "Before Mao we sometimes ate leaves, after liberation we did not." Regardless, Mahoney points out that Da Fo villagers recall the Great Leap Forward as a period of famine and death, and among those who survived in Da Fo were precisely those who could digest leaves.[38]

Lushan Conference

The initial impact of the Great Leap Forward was discussed at the Lushan Conference in July–August 1959. Although many of the more moderate leaders had reservations about the new policy, the only senior leader to speak out openly was Marshal Peng Dehuai. Mao responded to Peng's criticism of the Great Leap by dismissing Peng from his post as Defence Minister, denouncing Peng (who came from a poor peasant family) and his supporters as "bourgeois", and launching a nationwide campaign against "rightist opportunism". Peng was replaced by Lin Biao, who began a systematic purge of Peng's supporters from the military.

Consequences

The failure of agricultural policies, the movement of farmers from agricultural to industrial work, and weather conditions led to millions of deaths from severe famine. The economy, which had improved since the end of the civil war, was devastated, and in response to the severe conditions, there was resistance among the populace.

The effects on the upper levels of government in response to the disaster were complex, with Mao purging the Minister of National Defense Peng Dehuai in 1959, the temporary promotion of Lin Biao, Liu Shaoqi, and Deng Xiaoping, and Mao losing some power and prestige following the Great Leap Forward, which led him to launch the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

Famine

Despite the harmful agricultural innovations, the weather was very favorable in 1958 and the harvest was also good. However, the amount of labor which was diverted to steel production and construction projects meant that much of the harvest was left to rot because it was not collected in some areas. This problem was exacerbated by a devastating locust swarm, which was caused when their natural predators were killed as part of the Four Pests Campaign.

Although actual harvests were reduced, local officials, under tremendous pressure to report record harvests to central authorities in response to the innovations, competed with each other to announce increasingly exaggerated results. These results were used as the basis for determining the amount of grain which would be taken by the State, supplied to the towns and cities and exported. This barely left enough grain for the peasants, and in some areas, starvation set in. A 1959 drought and flooding from the Yellow River in the same year also contributed to the famine.

During 1958–1960 China continued to be a substantial net exporter of grain, despite the widespread famine which was being experienced in the countryside, as Mao sought to maintain face and convince the outside world of the success of his plans. Foreign aid was refused. When the Japanese foreign minister told his Chinese counterpart Chen Yi about an offer of 100,000 tonnes of wheat which was going to be shipped away from public view, he was rebuffed. John F. Kennedy was also aware that the Chinese were exporting food to Africa and Cuba during the famine and he said "we've had no indication from the Chinese Communists that they would welcome any offer of food."[40]

With dramatically reduced yields, even urban areas received greatly reduced rations; however, mass starvation was largely confined to the countryside, where, as a result of drastically inflated production statistics, very little grain was left for the peasants to eat. Food shortages were bad throughout the country, but the provinces which had adopted Mao's reforms with the most vigor, such as Anhui, Gansu and Henan, tended to suffer disproportionately. Sichuan, one of China's most populous provinces, known in China as "Heaven's Granary" because of its fertility, is thought to have suffered the highest number of deaths from starvation due to the vigor with which provincial leader Li Jingquan undertook Mao's reforms. There are widespread oral reports, though little official documentation, of human cannibalism being practiced in various forms as a result of the famine.[41][42] Author Yan Lianke also claims that, while growing up in Henan during the Great Leap Forward, he was taught to "recognize the most edible kinds of bark and clay by his mother. When all of the trees had been stripped and there was no more clay, he learned that lumps of coal could appease the devil in his stomach, at least for a little while."[43]

The agricultural policies of the Great Leap Forward and the associated famine continued until January 1961, when, at the Ninth Plenum of the 8th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the restoration of agricultural production through a reversal of the Great Leap policies was started. Grain exports were stopped, and imports from Canada and Australia reduced the impact of the food shortages, at least in the coastal cities.

Famine deaths

The exact number of famine deaths is difficult to determine, and estimates range from upwards of 15 million to 55 million people.[4][44][45] Because of the uncertainties involved in estimating famine deaths caused by the Great Leap Forward or any famine, it is difficult to compare the severity of different famines. If an estimate of 30 million deaths is accepted, the Great Leap Forward was the deadliest famine in the history of China and in the history of the world.[46][47] This was partly due to China's large population. To put things into absolute and relative numerical perspective: in the Great Irish Famine, approximately 1 million[48] of a population of 8 million people died, or 12.5%. If, on the Great Chinese Famine, approximately 23 million of a population of 650 million people died, the percentage would be 3.5%.[4] Hence, the famine during the Great Leap Forward probably had the highest absolute death toll, though not the highest relative (percentage) one.

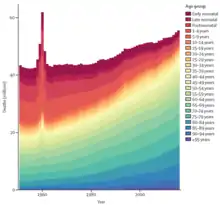

The Great Leap Forward reversed the downward trend in mortality that had occurred since 1950,[49] though even during the Leap, mortality may not have reached pre-1949 levels.[50] Famine deaths and the reduction in number of births caused the population of China to drop in 1960 and 1961.[51] This was only the third time in 600 years that the population of China had decreased.[52] After the Great Leap Forward, mortality rates decreased to below pre-Leap levels and the downward trend begun in 1950 continued.[49]

The severity of the famine varied from region to region. By correlating the increase in the death rates of different provinces, Peng Xizhe found that Gansu, Sichuan, Guizhou, Hunan, Guangxi, and Anhui were the hardest-hit regions, while Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tianjin, and Shanghai had the lowest increase in death rates during the Great Leap Forward (there was no data for Tibet).[53] Peng also noted that the increase in death rates in urban areas was about half the increase in death rates in rural areas.[53] Fuyang, a region in Anhui with a population of 8 million in 1958, had a death rate that rivaled Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge;[54] According to Chinese government reports in the Fuyang Party History Research Office, between the years 1959 and 1961, 2.4 million people from Fuyang died from the famine.[55] On the other hand, the Gao Village in the Jiangxi Province there was a famine, but no one actually died of starvation.[56]

Deaths by violence

Not all deaths during the Great Leap were from starvation. Frank Dikötter, in his book Mao's Great Famine, estimates that at least 2.5 million people were beaten or tortured to death and one million to three million committed suicide.[57][58] He provided some illustrative examples and claimed that in Xinyang, where over a million died in 1960, 6–7% (around 67,000) of these were beaten to death by the militias. In Daoxian county, 10% of those who died had been "buried alive, clubbed to death or otherwise killed by party members and their militia." In Shimen county, around 13,500 died in 1960, of these 12% were "beaten or driven to their deaths."[59] Dikötter's claims have been disputed by Felix Wemheur.[7] In accounts documented by Yang Jisheng, people were beaten or killed for rebelling against the government, reporting the real harvest numbers, for sounding alarm, for refusing to hand over what little food they had left, for trying to flee the famine area, for begging food or as little as stealing scraps or angering officials.[42][60]

In the book Tombstone, a cycle of starvation and violence was documented during the Great Leap Forward.[61]

Methods of estimating the death toll and sources of error

| Deaths (millions) |

Author(s) | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | Houser, Sands, and Xiao[62] | 2005 |

| 18 | Yao[63] | 1999 |

| 23 | Peng[64] | 1987 |

| 27 | Coale[49] | 1984 |

| 30 | Ashton, et al.[46] | 1984 |

| 30 | Banister[65] | 1987 |

| 30 | Becker[66] | 1996 |

| 32.5 | Cao[67] | 2005 |

| 36 | Yang[60] | 2008 |

| 38 | Chang and Halliday[68] | 2005 |

| 38 | Rummel[69] | 2008 |

| 45 minimum | Dikötter[44][58] | 2010 |

| 43 to 46 | Chen[70] | 1980 |

| 55 | Yu Xiguang[45][71] | 2005 |

Some outlier estimates include 11 million by Utsa Patnaik, an Indian Marxist economist,[72] 3.66 million by Sun Jingxian (孙经先), a Chinese mathematician,[73] and 2.6–4 million by Yang Songlin (杨松林), a Chinese historian and political economist.[74]

The number of famine deaths during the Great Leap Forward has been estimated with different methods. Banister, Coale, and Ashton et al. compare age cohorts from the 1953, 1964, and 1982 censuses, yearly birth and death records, and results of the 1982 1:1000 fertility survey. From these they calculate excess deaths above a death rate interpolated between pre- and post-Leap death rates. All involve corrections for perceived errors inherent in the different data sets.[75][76][77] Peng uses reported deaths from the vital statistics of 14 provinces, adjusts 10% for under reporting, and expands the result to cover all of China assuming similar mortality rates in the other provinces. He uses 1956/57 death rates as the baseline death rate rather than an interpolation between pre- and post-GLF death rates.[78]

Houser, Sands, and Xiao in their 2005 research study using "provincial-level demographic panel data and a Bayesian empirical approach in an effort to distinguish the relative importance of weather and national policy on China's great demographic disaster" conclude that "in aggregate, from 1959 to 1961 China suffered about 14.8 million excess deaths. Of those, about 69% (or 10.3 million) seem attributable to effects stemming from national policies."[62]: 156

Cao uses information from "local annals" to determine for each locality the expected population increase from normal births and deaths, the population increase due to migration, and the loss of population between 1958 and 1961. He then adds the three figures to determine the number of excess deaths during the period 1959–1961.[79] Chang and Halliday use death rates determined by "Chinese demographers" for the years 1957–1963, subtract the average of the pre-and post-Leap death rates (1957, 1962, and 1963) from the death rates of each of the years 1958–1961, and multiply each yearly excess death rate by the year's population to determine excess deaths.[80]

Chen was part of a large investigation by the System Reform Institute think tank (Tigaisuo) which "visited every province and examined internal Party documents and records."[81]

Becker, Rummel, Dikötter, and Yang each compare several earlier estimates. Becker considers Banister's estimate of 30 million excess deaths to be "the most reliable estimate we have".[66] Rummel initially took Coale's 27 million as a "most likely figure",[82] then accepted the later estimate of 38 million by Chang and Halliday after it was published.[83] Dikötter judged Chen's estimate of 43 to 46 million to be "in all likelihood a reliable estimate."[84] He also claimed that at least 2.5 million of these deaths were caused by beatings, tortures, or summary executions.[85] On the other hand, Daniel Vukovich asserts that this claim is coming from a problematic and unverified reference, because Chen simply threw that number as an "estimate" during an interview and because Chen hasn't published any scholarly work on the subject.[86] Yang takes Cao's, Wang Weizhi's, and Jin Hui's estimates ranging from 32.5 to 35 million excess deaths for the period 1959–1961, adds his own estimates for 1958 (0.42 million) and 1962 (2.23 million) "based on official figures reported by the provinces" to get 35 to 37 million, and chooses 36 million as a number that "approaches the reality but is still too low."[60]

Estimates contain several sources of error. National census data was not accurate and even the total population of China at the time was not known to within 50 million to 100 million people.[87] The statistical reporting system had been taken over by party cadre from statisticians in 1957,[88] making political considerations more important than accuracy and resulting in a complete breakdown in the statistical reporting system.[88][89][90][91][92] Population figures were routinely inflated at the local level, often in order to obtain increased rations of goods.[84] During the Cultural Revolution, a great deal of the material in the State Statistical Bureau was burned.[88]

According to Jasper Becker, under-reporting of deaths was also a problem. The death registration system, which was inadequate before the famine,[93] was completely overwhelmed by the large number of deaths during the famine.[93][94][95] In addition, he claims that many deaths went unreported so that family members of the deceased could continue to draw the deceased's food ration and that counting the number of children who both were born and died between the 1953 and 1964 censuses is problematic.[94] However, Ashton, et al. believe that because the reported number of births during the GLF seems accurate, the reported number of deaths should be accurate as well.[96] Massive internal migration made both population counts and registering deaths problematic,[94] though Yang believes the degree of unofficial internal migration was small[97] and Cao's estimate takes internal migration into account.[79]

Coale's, Banister's, Ashton et al.'s, and Peng's figures all include adjustments for demographic reporting errors, though Dikötter, in his book Mao's Great Famine, argues that their results, as well as Chang and Halliday's, Yang's, and Cao's, are still underestimates.[98] The System Reform Institute's (Chen's) estimate has not been published and therefore it cannot be verified.[79]

Causes of the famine and responsibility

The policies of the Great Leap Forward, the failure of the government to respond quickly and effectively to famine conditions, as well as Mao's insistence on maintaining high grain export quotas in the face of clear evidence of poor crop output were responsible for the famine. There is disagreement over how much, if at all, weather conditions contributed to the famine.

Yang Jisheng, a former communist party member and former reporter for the official Chinese news agency Xinhua, puts the blame squarely on Maoist policies and the political system of totalitarianism,[42] such as diverting agricultural workers to steel production instead of growing crops, and exporting grain at the same time.[99][100] During the course of his research, Yang uncovered that some 22 million tons of grain was held in public granaries at the height of the famine, reports of the starvation went up the bureaucracy only to be ignored by top officials, and the authorities ordered that statistics be destroyed in regions where population decline became evident.[101]

Economist Steven Rosefielde argues that Yang's account "shows that Mao's slaughter was caused in considerable part by terror-starvation; that is, voluntary manslaughter (and perhaps murder) rather than innocuous famine."[102] Yang claims that local party officials were indifferent to the large number of people dying around them, as their primary concern was the delivery of grain, which Mao wanted to use to pay back debts to the USSR totaling 1.973 billion yuan. In Xinyang, people died of starvation at the doors of grain warehouses.[103] Mao refused to open the state granaries as he dismissed reports of food shortages and accused the "rightists" and the kulaks of conspiring to hide grain.[104]

From his research into records and talks with experts at the meteorological bureau, Yang concludes that the weather during the Great Leap Forward was not unusual compared to other periods and was not a factor.[105] Yang also believes that the Sino-Soviet split was not a factor because it did not happen until 1960, when the famine was well under way.[105]

Chang and Halliday argue that "Mao had actually allowed for many more deaths. Although slaughter was not his purpose with the Leap, he was more than ready for myriad deaths to result, and had hinted to his top echelon that they should not be too shocked if they happened."[106] Democide historian R.J. Rummel had originally classified the famine deaths as unintentional.[107] In light of evidence provided in Chang and Halliday's book, he now believes that the mass human deaths associated with the Great Leap Forward constitute democide.[108] On the other hand, scholars Gregor Benton and Lin Chun, in a critical response to Chang and Halliday, state that there is no proof that Mao intended to let people die or that he was indifferent to their deaths.[109]

According to Frank Dikötter, Mao and the Communist Party knew that some of their policies were contributing to the starvation.[110] Foreign minister Chen Yi said of some of the early human losses in November 1958:[111]

Casualties have indeed appeared among workers, but it is not enough to stop us in our tracks. This is the price we have to pay, it's nothing to be afraid of. Who knows how many people have been sacrificed on the battlefields and in the prisons [for the revolutionary cause]? Now we have a few cases of illness and death: it's nothing!

In the later book, Tombstone by Yang Jisheng, "36 million Chinese starved to death in the years between 1958 and 1962, while 40 million others failed to be born, which means that “China’s total population loss during the Great Famine then comes to 76 million.”[112][113]

Mao's efforts to cool the Leap in late 1958 met resistance within the Party and when Mao proposed a scaling down of steel targets, "many people just wouldn't change and wouldn't accept it".[114] Thus, according to historian Tao Kai, the Leap "wasn't the problem of a single person, but that many people had ideological problems". Tao also pointed out that "everyone was together" on the anti-rightist campaign and only a minority didn't approve of the Great Leap's policies or put forth different opinions.[114] Jean-Louis Margolin[115] suggests that the actions of the Chinese Communist Party under Mao in the face of widespread famine imitated the policies of the Soviet Communist Party under Joseph Stalin (whom Mao greatly admired) nearly three decades earlier during the Soviet famine of 1932-33. At that time, the U.S.S.R. exported grain for international propaganda purposes despite millions dying of starvation across southern areas of the Soviet Union:

Net grain exports, principally to the U.S.S.R., rose from 2.7 million tons in 1958 to 4.2 million in 1959, and in 1960 fell only to the 1958 level. In 1961, 6.8 million tons were actually imported, up from 66,000 in 1960, but this was still too little to feed the starving. Aid from the United States was refused for political reasons. The rest of the world, which could have responded easily, remained ignorant of the scale of the catastrophe. Aid to the needy in the countryside totaled less than 450 million yuan per annum, or 0.8 yuan per person, at a time when one kilo of rice on the free market was worth 2 to 4 yuan. Chinese Communism boasted that it could move mountains and tame nature, but it left these faithful to die.[115]

During a secret meeting in Shanghai in 1959, Mao demanded the state procurement of one-third of all grain to feed the cities and satisfy foreign clients, and noted that "If you don't go above a third, people won't rebel." In the context of discussing industrial enterprises,[116] Mao also stated at the same meeting:[117]

When there is not enough to eat people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill.[118]

However, Anthony Garnaut clarifies that Dikötter's interpretation of Mao's quotation, "It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill." not only ignores the substantial commentary on the conference by other scholars and several of its key participants, but defies the very plain wording of the archival document in his possession on which he hangs his case.[119]

Benjamin Valentino writes that like in the USSR during the famine of 1932–33, peasants were confined to their starving villages by a system of household registration,[120] and the worst effects of the famine were directed against enemies of the regime.[37] Those labeled as "black elements" (religious leaders, rightists, rich peasants, etc.) in any previous campaign were given the lowest priority in the allocation of food, and therefore died in the greatest numbers.[37] Drawing from Jasper Becker's book Hungry Ghosts, genocide scholar Adam Jones states that "no group suffered more than the Tibetans" from 1959 to 1962.[121]

Ashton, et al. write that policies leading to food shortages, natural disasters, and a slow response to initial indications of food shortages were to blame for the famine.[122] Policies leading to food shortages included the implementation of the commune system and an emphasis on non-agricultural activities such as backyard steel production.[122] Natural disasters included drought, flood, typhoon, plant disease, and insect pest.[123] The slow response was in part due to a lack of objective reporting on the agricultural situation,[124] including a "nearly complete breakdown in the agricultural reporting system".[90]

This was partly caused by strong incentives for officials to over-report crop yields.[125] The unwillingness of the Central Government to seek international aid was a major factor; China's net grain exports in 1959 and 1960 would have been enough to feed 16 million people 2000 calories per day.[123] Ashton, et al. conclude that "It would not be inaccurate to say that 30 million people died prematurely as a result of errors of internal policy and flawed international relations."[124]

Mobo Gao suggested that the Great Leap Forward's terrible effects came not from malignant intent on the part of the Chinese leadership at the time, but instead related to the structural nature of its rule, and the vastness of China as a country. Gao says "the terrible lesson learnt is that China is so huge and when it is uniformly ruled, follies or wrong policies will have grave implications of tremendous magnitude".[56]

The PRC government's official web portal places the responsibility for the "serious losses" to "country and people" of 1959–1961 (without mentioning famine) mainly on the Great Leap Forward and the anti-rightist struggle, and lists weather and cancellation of contracts by the Soviet Union as contributing factors.[126]

Impact on economy

Negative

According to Frank Dikotter, The Great Leap led to the greatest destruction of real estate in human history, outstripping any of the bombing campaigns from World War II.[127] Approximately 30% to 40% of all houses were turned to rubble.[128] Frank Dikötter states that "homes were pulled down to make fertilizer, to build canteens, relocate villagers, straighten roads, make place for a better future, or punish their owners."[127]

In agrarian policy, the failures of food supply during the Great Leap were met by a gradual de-collectivization in the 1960s that foreshadowed further de-collectivization under Deng Xiaoping. Political scientist Meredith Jung-En Woo argues: "Unquestionably the regime failed to respond in time to save the lives of millions of peasants, but when it did respond, it ultimately transformed the livelihoods of several hundred million peasants (modestly in the early 1960s, but permanently after Deng Xiaoping's reforms subsequent to 1978)."[129]

Despite the risks to their careers, some Communist Party members openly laid blame for the disaster at the feet of the Party leadership and took it as proof that China must rely more on education, acquiring technical expertise and applying bourgeois methods in developing the economy. Liu Shaoqi made a speech in 1962 at "Seven Thousand Cadres Conference" criticizing that "The economic disaster was 30% fault of nature, 70% human error."[130]

A 2017 paper by two Peking University economists found "strong evidence that the unrealistic yield targets led to excessive death tolls from 1959 to 1961, and further analysis shows that yield targets induced the inflation of grain output figures and excessive procurement. We also find that Mao's radical policy caused serious deterioration in human capital accumulation and slower economic development in the policy-affected regions decades after the death of Mao."[131]

A dramatic decline in grain output continued for several years, involving in 1960–61 a drop in output of more than 25 percent. Causes of this drop are found in both natural disaster and government policy.[46]

Positive

According to Joseph Ball, writing in Monthly Review, there is a good argument to suggest that the policies of the Great Leap Forward did a lot to sustain China's overall economic growth, after an initial period of disruption.[132] Official Chinese statistics show that after the end of the Leap in 1962, industrial output value had doubled; the gross value of agricultural products increased by 35 percent; steel production in 1962 was between 10.6 million tons or 12 million tons; investment in capital construction rose to 40 percent from 35 percent in the First Five-Year Plan period; the investment in capital construction was doubled; and the average income of workers and farmers increased by up to 30 percent.[133] Additionally, there was significant capital construction (especially in iron, steel, mining and textile enterprises) that ultimately contributed greatly to China's industrialization.[114] The Great Leap Forward period also marked the initiation of China's rapid growth in tractor and fertilizer production.[134]

Resistance

There were various forms of resistance to the consequences of the Great Leap Forward. Several provinces saw armed rebellion,[135][136] though these rebellions never posed a serious threat to the Central Government.[135] Rebellions are documented to have occurred in Henan, Shandong, Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, Fujian, and Yunnan provinces and in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.[137][138] In Henan, Shandong, Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan, these rebellions lasted more than a year,[138] with the Spirit Soldier rebellion of 1959 being one of the few larger-scale uprisings.[139] There was also occasional violence against cadre members.[136][140] Raids on granaries,[136][140] arson and other vandalism, train robberies, and raids on neighboring villages and counties were common.[140]

According to Ralph Thaxton, professor of politics at Brandeis University, villagers turned against the CCP during and after the Great Leap, seeing it as autocratic, brutal, corrupt, and mean-spirited.[9] According to Thaxton, the CCP's policies included plunder, forced labor, and starvation, which led villagers "to think about their relationship with the Communist Party in ways that do not bode well for the continuity of socialist rule."[9]

Often, villagers composed doggerel to show their defiance to the regime, and "perhaps, to remain sane." During the Great Leap, one jingle ran: "Flatter shamelessly—eat delicacies.... Don't flatter—starve to death for sure."[34]

Impact on the government

Officials were prosecuted for exaggerating production figures, although punishments varied. In one case, a provincial party secretary was dismissed and prohibited from holding higher office. A number of county-level officials were publicly tried and executed.[141]

Mao stepped down as State Chairman of the PRC on April 27, 1959, but remained CCP Chairman. Liu Shaoqi (the new PRC Chairman) and reformist Deng Xiaoping (CCP General Secretary) were left in charge to change policy to bring economic recovery. Mao's Great Leap Forward policy was openly criticized at the Lushan party conference by one person. Criticism from Minister of National Defense Peng Dehuai, who, discovered that people from his home province starved to death caused him to write a letter to Mao to ask for the policies to be adapted.[61] After the Lushan showdown, Mao replaced Peng with Lin Biao and Peng was sent off into obscurity.[61]

However, by 1962, it was clear that the party had changed away from the extremist ideology that led to the Great Leap. During 1962, the party held a number of conferences and rehabilitated most of the deposed comrades who had criticized Mao in the aftermath of the Great Leap. The event was again discussed, with much self-criticism, and the contemporary government called it a "serious [loss] to our country and people" and blamed the cult of personality of Mao.

at the Lushan conference of 1959. Peng Dehuai, one of the great marshals of the Chinese civil war against the nationalists, was a strong supporter of the Leap. But the discovery that people from his own home area were starving to death prompted him to write to Mao to ask for the policies to be adapted. Mao was furious, reading the letter out in public and demanding that his colleagues in the leadership line up either behind him or Peng. Almost to a man, they supported Mao, with his security chief Kang Sheng declaring of the letter: "I make bold to suggest that this cannot be handled with lenience."

In particular, at the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference in January – February 1962, Mao made a self-criticism and re-affirmed his commitment to democratic centralism. In the years that followed, Mao mostly abstained from the operations of government, making policy largely the domain of Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. Maoist ideology took a back seat in the Communist Party, until Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966 which marked Mao's political comeback.

See also

- List of campaigns of the Chinese Communist Party

- The Black Book of Communism

- Mass killings of landlords under Mao Zedong

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Ryazan miracle

- Virgin Lands Campaign, contemporary program in the Soviet Union

References

- Kte'pi, Bill (2011), "Chinese Famine (1907)", Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 70–71, doi:10.4135/9781412994064, ISBN 978-1412971010,

The Chinese Famine of 1907 is the second-worst famine in recorded history, with an estimated death toll of around 25 million people; this exceeds the lowest estimates for the death toll of the later Great Chinese Famine, meaning that the 1907 famine could actually be the worst in history.

- Smil, Vaclav (18 December 1999). "China's great famine: 40 years later". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 319 (7225): 1619–1621. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1127087. PMID 10600969.

- Meng, Xin; Qian, Nancy; Yared, Pierre (2015). "The Institutional Causes of China's Great Famine, 1959–1961" (PDF). Review of Economic Studies. 82 (4): 1568–1611. doi:10.1093/restud/rdv016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Hasell, Joe; Roser, Max (10 October 2013). "Famines". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Mirsky, Jonathan (7 December 2012). "Unnatural Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Dikötter, Frank. "Mao's Great Famine: Ways of Living, Ways of Dying" (PDF). Dartmouth University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- Wemheuer, Felix; Dikötter, Frank (2011-07-01). "Sites of Horror: Mao's Grear Famine [with Response]". The China Journal. 66: 155–164. doi:10.1086/tcj.66.41262812. ISSN 1324-9347. S2CID 141874259.

- Gráda, Cormac Ó (2007). "Making Famine History". Journal of Economic Literature. 45 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1257/jel.45.1.5. hdl:10197/492. ISSN 0022-0515. JSTOR 27646746. S2CID 54763671.

- Mirsky, Jonathan. "The China We Don't Know Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine." New York Review of Books Volume 56, Number 3. February 26, 2009.

- Perkins, Dwight (1991). "China's Economic Policy and Performance" Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. Chapter 6 in The Cambridge History of China, Volume 15, ed. by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank and Denis Twitchett. Cambridge University Press.

- GDP growth in China 1952–2015 Archived 2013-07-16 at the Wayback Machine The Cultural Revolution was the other period during which the economy shrank.

- Perkins (1991). pp. 483–486 for quoted text, p. 493 for growth rates table.

- "1975年那个黑色八月(上)(史海钩沉)". Renmin Wang (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2020-05-06. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- IChemE. "Reflections on Banqiao". Institution of Chemical Engineers. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- Chang, Jung and Halliday, Jon (2005). Mao: The Unknown Story, Knopf. p. 435. ISBN 0-679-42271-4.

- Li, Kwok-sing (1995). A glossary of political terms of the People's Republic of China. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Translated by Mary Lok. pp. 47–48.

- Chan, Alfred L. (2001). Mao's crusade: politics and policy implementation in China's great leap forward. Studies on contemporary China. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-924406-5. Archived from the original on 2019-06-12. Retrieved 2011-10-20.

- Gabriel, Satya J. (1998). "Political Economy of the Great Leap Forward: Permanent Revolution and State Feudal Communes". Mount Holyoke College.

- Lieberthal, Kenneth (1987). "The Great Leap Forward and the split in the Yenan leadership". The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949–1965. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 14, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-521-24336-0. "Thus, the [1957] Anti-Rightist Campaign in both urban and rural areas bolstered the position of those who believed that proper mobilization of the populace could accomplish tasks that the 'bourgeois experts' dismissed as impossible."

- Lieberthal (1987). p. 304.

- Thaxton, Ralph A. Jr. (2008). Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China: Mao's Great Leap Forward Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-521-72230-6.

- Alfred L. Chan (2001). Mao's Crusade : Politics and Policy Implementation in China's Great Leap Forward. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–74. ISBN 978-0-19-155401-8. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Lardy, R. Nicholas; Fairbank, K. John (1987). "The Chinese economy under stress, 1958–1965". In Roderick MacFarquhar (ed.). The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China 1949–1965. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-521-24336-0.

- Lardy and Fairbank (1987). p. 368.

- Lardy and Fairbank (1987). pp. 38–87.

- Li Zhi-Sui (2011). The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 272–274, 278. ISBN 978-0-307-79139-9. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Dikötter, Frank (2010). p. 33.

- Weiqing, Jiang (1996). Qishi nian zhengcheng: Jiang Weiqing huiyilu [A seventy-year journey: The memoirs of Jiang Weiqing] Jiangsu renmin chubanshe. p. 421. ISBN 7-214-01757-1 is the source of Dikötter's quote. Mao, who had been continually interrupting, was speaking here in praise of Jiang Weiqing's plan (which called for moving 300 million cubic meters). Weiqing states that the others' plans were "exaggerations", though Mao would go to criticize those cadres with objections to high targets at the National Congress in May (see p. 422).

- MacFarquhar, Roderick (1983). The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Vol. 2 Columbia University Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-231-05717-2.

- Dikötter (2010). p. 39.

- Hinton, William (1984). Shenfan: The Continuing Revolution in a Chinese Village. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 236–245. ISBN 978-0-394-72378-5.

- Hinton 1984, pp. 234–240, 247–249

- Friedman, Edward; Pickowicz, Paul G.; and Selden, Mark (2006). Revolution, Resistance, and Reform in Village China. Yale University Press.

- Mirsky, Jonathan. "China: The Shame of the Villages" Archived 2015-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Review of Books, Volume 53, Number 8. 11 May 2006

- Thaxton 2008, p. 212.

- Jasper Becker. Systematic genocide. Archived 2012-04-11 at the Wayback Machine The Spectator, September 25, 2010.

- Valentino (2004). p. 128.

- Mahoney, Josef Gregory (2009). "Ralph A. Thaxton, Jr., Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China: Mao's Great Leap Forward, Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village". Journal of Chinese Political Science (book review). Springer. 14 (3): 319–320. doi:10.1007/s11366-009-9064-8. S2CID 153540137.

- Dicker, Daniel (2018). "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017" (PDF). The Lancet. 392 (10159): 1684–1735. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31891-9. PMC 6227504. PMID 30496102.

- Dikötter, Frank (2010). pp. 114–115.

- Bernstein, Richard. Horror of a Hidden Chinese Famine Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. New York Times February 5, 1997. Bernstein reviews Hungry Ghosts by Jasper Becker.

- Branigan, Tania (1 January 2013). "China's Great Famine: the true story". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Fan, Jiayang (15 October 2018). "Yan Lianke's Forbidden Satires of China". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Dikötter, Frank. Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62. Walker & Company, 2010. p. xii ("at least 45 million people died unnecessarily") p. xiii ("6 to 8 percent of the victims were tortured to death or summarily killed—amounting to at least 2.5 million people.") p. 333 ("a minimum of 45 million excess deaths"). ISBN 0-8027-7768-6.

- "La Chine creuse ses trous de mémoire". La Liberation (in French). 2011-06-17. Archived from the original on 2019-10-02. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- Ashton, Hill, Piazza, and Zeitz (1984). Famine in China, 1958–61. Population and Development Review, Volume 10, Number 4 (December 1984). p. 614. "Demographic evidence indicates that famine during 1958–61 caused almost 30 million premature deaths in China and reduced fertility very significantly. Data on food availability suggest that, in contrast to many other famines, a root cause of this one was a dramatic decline in grain output that continued for several years, involving in 1960–61 a drop in output of more than 25 percent. Causes of this drop are found in both natural disaster and government policy."

- Yang, Jisheng (2010) "The Fatal Politics of the PRC's Great Leap Famine: The Preface to Tombstone" Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Journal of Contemporary China. Volume 19 Issue 66. pp. 755–776. Retrieved 3 Sep 2011. Yang excerpts Sen, Amartya (1999). Democracy as a universal value. Journal of Democracy 10(3), pp. 3–17 who calls it "the largest recorded famine in world history: nearly 30 million people died".

- Wright, John W. (gen ed) (1992). The Universal Almanac. The Banta Company. Harrisonburg, Va. p. 411.

- Coale, J. Ansley (1984). Rapid Population Change in China, 1952–1982. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. p. 7. Coale estimates 27 million deaths: 16 million from direct interpretation of official Chinese vital statistics followed by an adjustment to 27 million to account for undercounting.

- Li, Minqi (2009). The Rise of China and the Demise of the Capitalist World Economy. Monthly Review Press. p. 41 ISBN 978-1-58367-182-5. Li compares official crude death rates for the years 1959–1962 (11.98, 14.59, 25.43, and 14.24 per thousand, respectively) with the "nationwide crude death rate reported by the Nationalist government for the years 1936 and 1938 (27.6 and 28.2 per thousand, respectively).

- Ashton (1984). p. 615, Banister (1987). p. 42, both get their data from Statistical Yearbook of China 1983 published by the State Statistical Bureau.

- Banister, Judith (1987). China's Changing Population. Stanford University Press. Stanford. p. 3.

- Peng (1987). pp. 646–648

- Dikötter, Frank (2010-10-13).Mao's Great Famine (Complete) Archived 2011-06-16 at the Wayback Machine. Asia Society. Lecture by Frank Dikötter (Video).

- Zhou Xun. Forgotten Voices of Mao's Great Famine, 1958–1962: An Oral History. 2013. pp. 138–139, 292

- Gao, Mobo (2007). Gao Village: Rural life in modern China. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824831929

- Dikötter (2010). pp. 298, 304.

- "45 million died in Mao's Great Leap Forward, Hong Kong historian says in new book". 2018-12-06. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

At least 45 million people died unnecessary deaths during China's Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962, including 2.5 million tortured or summarily killed, according to a new book by a Hong Kong scholar. Mao's Great Famine traces the story of how Mao Zedong's drive for absurd targets for farm and industrial production and the reluctance of anyone to challenge him created the conditions for the countryside to be emptied of grain and millions of farmers left to starve.

- Dikötter (2010). pp. 294, 297.

- Yang Jisheng (2012). Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958–1962 (Kindle edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 430. ISBN 978-1466827790.

- "Tombstone: The Untold Story of Mao's Great Famine by Yang Jisheng – review". The Guardian. 2012-12-07. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- Houser, D.; Sands, B.; Xiao, E. (2009-02-01). "Three parts natural, seven parts man-made: Bayesian analysis of China's Great Leap Forward demographic disaster". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 69 (2): 148–159. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2007.09.008. ISSN 0167-2681.This estimate concludes that the excess death count by manmade causes numbers some 10.3 million, 69% of the total estimated deaths.

- Yao, Shujie (1999). "A Note on the Causal Factors of China's Famine in 1959–1961". Journal of Political Economy. 107 (6): 1365–1369. doi:10.1086/250100. JSTOR 10.1086/250100. S2CID 17546168 – via JSTOR.

- Peng Xizhe (1987). Demographic Consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China's Provinces. Population and Development Review Volume 13 Number 4 (Dec 1987). pp. 648–649.

- Banister, Judith (1987). China's Changing Population. Stanford University Press. pp. 85, 118.

- Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Paperbacks. pp. 270, 274. ISBN 0-8050-5668-8.

- Dikötter (2010) pp. 324–325. Dikötter cites Cao Shuji (2005). Da Jihuang (1959–1961): nian de Zhongguo renkou (The Great Famine: China's Population in 1959–1961). Hong Kong. Shidai guoji chuban youxian gongsi. p. 281

- Chang and Halliday (2005). Stuart Schram believes their estimate "may well be the most accurate." (Stuart Schram, "Mao: The Unknown Story". The China Quarterly (189): 207. Retrieved 7 Oct 2007.)

- Rummel, R.J. (2008-11-24). Reevaluating China's Democide to 73,000,000 Archived 2018-06-30 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 Feb 2013.

- Becker (1996). pp. 271–272. From an interview with Chen Yizi.

- Yu Xiguang, Da Yuejin Kurezi, Shidai Chaoliu Chubanshe, Hong Kong (2005)

- "Ideological Statistics: Inflated Death Rates of China's Famine, the Russian one Ignored". Socialist Economist.

- Sun 2016.

- Yang 2021.

- Banister (1987). pp. 118–120.

- Coale (1984). pp. 1, 7.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). pp. 613, 616–619.

- Peng (1987). pp. 645, 648–649. Peng used the pre-Leap death rate as a base line under the assumption that the decrease after the Great Leap to below pre-Leap levels was caused by Darwinian selection during the massive deaths of the famine. He writes that if this drop was instead a continuation of the decreasing mortality in the years prior to the Great Leap, his estimate would be an underestimate.

- Yang Jisheng (2012). Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958–1962 (Kindle edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 427. ISBN 978-1466827790.

- Chang and Halliday (2005) p. 438

- Becker (1996). pp. 271–272.

- Rummel (1991). p. 248.

- Reevaluated democide totals for 20th C. and China Archived 2014-08-27 at the Wayback Machine Rudy J. Rummel Retrieved 22 Oct 2016

- Dikötter (2010) p. 333.

- Bianco, Lucien (2011-07-30). "Frank Dikötter, Mao's Great Famine, The History of China's most devastating catastrophe, 1958–62". China Perspectives. 2011 (2): 74–75. doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.5585. ISSN 2070-3449.

- Vukovich 2013, p. 70.

- Rummel (1991). p. 235.

- Banister (1987). p. 13.

- Peng (1987). p. 656.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). p. 630.

- Dikötter (2010) p. 132.

- Becker (1996). p. 267.

- Banister (1987). p. 85.

- Becker (1996). pp. 268–269.

- Dikötter (2010) p. 327.

- Ashton et al. (1984). p. 617.

- Yang (2012) p. 430.

- Dikotter (2010) p. 324. (Dikötter does not mention Coale on this page).

- Yu, Verna (2008). "Chinese author of book on famine braves risks to inform new generations Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine." The New York Times, November 18, 2008. Yu writes about Tombstone and interviews author Yang Jisheng.

- Applebaum, Anne (2008). "When China Starved Archived 2012-11-07 at the Wayback Machine." The Washington Post, August 12, 2008. Applebaum writes about Tombstone by Yang Jishen.

- Link, Perry (2010). "China: From Famine to Oslo" Archived 2015-11-26 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Review of Books, December 16, 2010.

- Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 0-415-77757-7.

- O'Neill, Mark (2008). A hunger for the truth: A new book, banned on the mainland, is becoming the definitive account of the Great Famine. China Elections, 10 February 2012 Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Paperbacks. p. 86. ISBN 0-8050-5668-8.

- Johnson, Ian (2010). Finding the Facts About Mao's Victims Archived 2015-10-29 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Review of Books (Blog), December 20, 2010. Retrieved 4 Sep 2011. Johnson interviews Yang Jishen. (Provincial and central archives).

- Chang ang Halliday (2005). p. 457.

- Rummel (1991). pp. 249–250.

- Rummel, R.J. (2005-11-30). "Getting My Reestimate Of Mao's Democide Out". Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- Benton, Gregor; Chun, Lin (2013). Was Mao Really a Monster?: The Academic Response to Chang and Halliday's "Mao: The Unknown Story". Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-134-00662-5.

Millions of people died during the famine because of Mao's mismanagement, but there is no proof that he intended to let people die or was indifferent to their deaths (see section 14).

- Dikötter, Frank. Mao's Great Famine, Key Arguments Archived 2011-08-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dikötter (2010). p. 70.

- Mirsky, Jonathan (2012-12-07). "Unnatural Disaster". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- "Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine 1958–1962, by Yang Jisheng, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012, 629 pp".

- Joseph, William A. (1986). "A Tragedy of Good Intentions: Post-Mao Views of the Great Leap Forward". Modern China. 12 (4): 419–457. doi:10.1177/009770048601200401. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 189257. S2CID 145481585.

- Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999). "China: A Long March Into Night". The Black Book of Communism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 495–496. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2

- "Wilson Center Digital Archive". digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- Dikötter (2010). p. 88.

- "Looking for Great Leap "smoking gun" document | H-PRC | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- Garnaut, Anthony (2013). "Hard facts and half-truths: The new archival history of China's Great Famine". China Information. 27 (2): 223–246. doi:10.1177/0920203X13485390. S2CID 143503403.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2004). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-8014-3965-5.

- Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge, 2nd edition (2010). p. 96. ISBN 0-415-48619-X.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). pp. 624, 625.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). p. 629.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). p. 634.

- Ashton, et al. (1984). p. 626.

- Chinese Government's Official Web Portal (English). China: a country with 5,000-year-long civilization Archived June 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 3 Sep 2011. "It was mainly due to the errors of the great leap forward and of the struggle against "Right opportunism" together with a succession of natural calamities and the perfidious scrapping of contracts by the Soviet Government that our economy encountered serious difficulties between 1959 and 1961, which caused serious losses to our country and people."

- Dikötter (2010). pp. xi, xii.

- Dikötter (2010). p. 169.

- Woo-Cummings, Meredith Archived 2013-11-29 at archive.today (2002). "The Political Ecology of Famine: The North Korean Catastrophe and Its Lessons" (PDF). 2015-01-22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-03-18. Retrieved 2006-03-13. (807 KB), ADB Institute Research Paper 31, January 2002. Retrieved 3 Jul 2006.

- Twentieth Century China: Third Volume. Beijing, 1994. p. 430.

- Liu, Chang; Zhou, Li-An (2017-11-21). "Estimating the Short- and Long-Term Effects of Mso Zedong's Economic Radicalism". Rochester, NY. SSRN 3075015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ball, Joseph (21 September 2006). "Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward?". Monthly Review.

There is a good argument to suggest that the policies of the Great Leap Forward actually did much to sustain China’s overall economic growth, after an initial period of disruption.

- People's Republic of China Yearbook. Vol. 29. Xinhua Publishing House. 2009. p. 340.

The 2nd Five-Year Plan (1958–1962) [...] Industrial output value had doubled; the gross value of agricultural products increased by 35 percent; steel production in 1962 was between 10.6 million tons or 12 million tons; investment in capital construction rose to 40 percent from 35 percent in the First Five-Year Plan period; the investment in capital construction was doubled; and the average income of workers and farmers increased by up to 30 percent.

- Lippit, Victor D. (1975). "The Great Leap Forward Reconsidered". Modern China. 1 (1): 92–115. doi:10.1177/009770047500100104. ISSN 0097-7004. JSTOR 188886. S2CID 143721256.

- Dikötter (2010) pp. 226–228.

- Rummel (1991). pp. 247–251.

- Dikötter (2010) pp. 226–228 (Qinghai, Tibet, Yunnan).

- Rummel (1991). pp. 247–251 (Honan, Shantung, Qinghai (Chinghai), Gansu (Kansu), Szechuan (Schechuan), Fujian), p. 240 (TAR).

- Smith (2015), p. 346.

- Dikötter (2010) pp. 224–226.

- Friedman, Edward; Pickowicz, Paul G.; Selden, Mark; and Johnson, Kay Ann (1993). Chinese Village, Socialist State. Yale University Press. p. 243. ISBN 0300054289/ As seen in Google Book Search Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- This article incorporates public domain text from the United States Library of Congress Country Studies. – China

Bibliography and further reading

| Library resources about Great Leap Forward |

- Ashton, Hill, Piazza, and Zeitz (1984). Famine in China, 1958–61. Population and Development Review, Volume 10, Number 4 (Dec., 1984), pp. 613–645.

- Bachman, David (1991). Bureaucracy, Economy, and Leadership in China: The Institutional Origins of the Great Leap Forward. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- [Bao] Sansan and Bette Bao Lord (1964). Eighth Moon: The True Story of a Young Girl's Life in Communist China, New York: Harper & Row.

- Chen, Lingchei Letty (2020). "The Great Leap Backward: Forgetting and Representing the Mao Years". New York: Cambria Press. Scholarly studies on memory writings and documentaries of the Mao years, victimhood narratives, perpetrator studies, ethics of bearing witness to atrocities.

- Courtois, Stephane, Andzej Paczkowski and Nicholas Werth (1999). The Black Book of Communism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 463–546. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2

- Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8050-5668-8

- Jung Chang and Jon Halliday. (2005) Mao: The Unknown Story, Knopf. ISBN 0-679-42271-4

- Dikötter, Frank (2010), Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62, Walker, ISBN 978-0-8027-7768-3

- Gao. Mobo (2007). Gao Village: Rural life in modern China. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3192-9

- Gao. Mobo (2008). The Battle for China's Past. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2780-8

- Kim, Seonghoon, Belton Fleisher, and Jessica Ya Sun. "The Long‐term Health Effects of Fetal Malnutrition: Evidence from the 1959–1961 China Great Leap Forward Famine." Health economics 26.10 (2017): 1264–1277. online

- Li. Minqi (2009). The Rise of China and the Demise of the Capitalist World Economy. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-182-5

- Li, Wei; Tao Yang, Dennis (2005). "The Great Leap Forward: Anatomy of a Central Planning Disaster" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 113 (4): 840–877. doi:10.1086/430804. S2CID 17274196. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28.

- Li, Zhisui (1996). The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Arrow Books Ltd.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick (1983). Origins of the Cultural Revolution: Vol 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peng, Xizhe. "Demographic consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China's Provinces." Population and development review 13.4 (1987): 639–670. online

- Shen, Zhihua, and Yafeng Xia. "The great leap forward, the people's commune and the Sino-Soviet split." Journal of contemporary China 20.72 (2011): 861–880.

- Smith, S.A. (2015). "Redemptive Religious Societies and the Communist State, 1949 to the 1980s". In Jeremy Brown; Matthew D. Johnson (eds.). Maoism at the Grassroots: Everyday Life in China's Era of High Socialism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 340–364. ISBN 978-0674287204.

- Short, Philip (2001). Mao: A Life. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6638-1

- Tao Yang, Dennis. (2008) "China's Agricultural Crisis and Famine of 1959–1961: A Survey and Comparison to Soviet Famines." Palgrave MacMillan, Comparative Economic Studies 50, pp. 1–29.

- Thaxton. Ralph A. Jr (2008). Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China: Mao's Great Leap Forward Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-72230-6

- Wertheim, Wim F (1995). Third World whence and whither? Protective State versus Aggressive Market. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis. 211 pp. ISBN 90-5589-082-0

- E. L Wheelwright, Bruce McFarlane, and Joan Robinson (Foreword), The Chinese Road to Socialism: Economics of the Cultural Revolution.

- Yang, Dali (1996). Calamity and Reform in China: State, Rural Society, and Institutional Change since the Great Leap Famine. Stanford University Press.

- Yang, Jisheng (2008). Tombstone (Mu Bei – Zhong Guo Liu Shi Nian Dai Da Ji Huang Ji Shi). Cosmos Books (Tian Di Tu Shu), Hong Kong.

- Yang, Jisheng (2010). "The Fatal Politics of the PRC's Great Leap Famine: The Preface to Tombstone". Journal of Contemporary China. 19 (66): 755–776. doi:10.1080/10670564.2010.485408. S2CID 144899172.

- Vukovich, Daniel (2013). China and Orientalism: Western Knowledge Production and the PRC. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-50593-5.

- Sun, Jingxian (2016). "Population Change during China's 'Three Years of Hardship' (1959 to 1961)" (PDF). Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations. 2: 453–500.