Gustav I of Sweden

Gustav I, born Gustav Eriksson of the Vasa noble family and later known as Gustav Vasa (12 May 1496[1] – 29 September 1560), was King of Sweden from 1523 until his death in 1560,[2] previously self-recognised Protector of the Realm (Riksföreståndare) from 1521, during the ongoing Swedish War of Liberation against King Christian II of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Gustav rose to lead the rebel movement following the Stockholm Bloodbath, where his father was executed. Gustav's election as king on 6 June 1523 and his triumphant entry into Stockholm eleven days later marked Sweden's final secession from the Kalmar Union.[3]

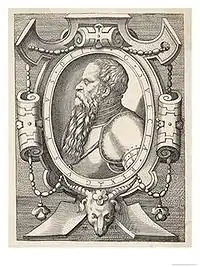

| Gustav I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jakob Bincks, 1542 | |

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 6 June 1523 – 29 September 1560 |

| Coronation | 12 January 1528 |

| Predecessor | Christian II |

| Successor | Eric XIV |

| Born | Gustav Eriksson 12 May 1496 Rydboholm Castle, Uppland or Lindholmen, Uppland, Sweden |

| Died | 29 September 1560 (aged 64) Tre Kronor, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Burial | 21 December 1560 Uppsala Cathedral, Uppsala, Sweden |

| Spouse | Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (m. 1531; died 1535) Margaret Leijonhufvud (m. 1536; died 1551) Catherine Stenbock (m. 1552) |

| Issue | Eric XIV of Sweden John III of Sweden Catherine, Countess of East Frisia Cecilia, Margravine of Baden-Rodemachern Prince Magnus, Duke of Östergötland Anna Maria, Countess Palatine of Veldenz Sophia, Duchess of Saxe-Lauenburg Elizabeth, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch Charles IX of Sweden |

| House | Vasa |

| Father | Erik Johansson Vasa |

| Mother | Cecilia Månsdotter |

| Religion | Lutheran (1523-1560) prev. Roman Catholic (1496-1523) |

As king, Gustav proved an energetic administrator with a ruthless streak not inferior to his predecessor's, brutally suppressing subsequent uprisings (three in Dalarna – which had once been the first region to support his claim to the throne – one in Västergötland, and one in Småland). He worked to raise taxes and bring about a Reformation in Sweden, replacing the prerogatives of local landowners, noblemen and clergy with centrally appointed governors and bishops. His 37-year rule, which was the longest of an adult Swedish king to that date (subsequently passed by Gustav V and Carl XVI Gustav) saw a complete break with not only the Danish - Norwegian supremacy but also the Roman Catholic Church, whose assets were nationalised, with the Lutheran Church of Sweden established under his personal control. He became the first truly autocratic native Swedish sovereign and was a skilled bureaucrat and propagandist, with tales of his largely fictitious adventures during the liberation struggle still widespread to this day. In 1544, he abolished Medieval Sweden's elective monarchy and replaced it with a hereditary monarchy under the House of Vasa, which held the Swedish throne until 1654. Three of his sons, Eric XIV, John III and Charles IX, held the kingship at different points.[4]

Gustav I has subsequently been labelled the founder of modern Sweden, and the "father of the nation". Gustav liked to compare himself to Moses, whom he believed to have also liberated his people and established a sovereign state. As a person, Gustav was known for ruthless methods and a bad temper, but also a fondness for music and had a certain sly wit and ability to outmaneuver and annihilate his opponents. He founded one of the oldest orchestras of the world, Kungliga Hovkapellet (Royal Court Orchestra); thus Royal housekeeping accounts from 1526 mention twelve musicians including wind players and a timpanist but no string players.[5] Today Kungliga Hovkapellet is the orchestra of the Royal Swedish Opera.[6][7]

Early life

Gustav Eriksson, a son of Cecilia Månsdotter Eka and Erik Johansson Vasa, was probably born in 1496. The birth most likely took place in Rydboholm Castle, northeast of Stockholm, the manor house of the father, Erik. The newborn got his name, Gustav, from Erik's grandfather Gustav Anundsson.[8]

Erik Johansson's parents were Johan Kristersson and Birgitta Gustafsdotter of the dynasties Vasa and Sture respectively, both dynasties of high nobility. Birgitta Gustafsdotter was the sister of Sten Sture the Elder, regent of Sweden, and their mother was a half-sister of King Charles VIII of Sweden. Being a relative and ally of uncle Sten Sture, Erik inherited the regent's estates in Uppland and Södermanland when the latter died in 1503. Although a member of a family with considerable properties since childhood, Gustav Eriksson would later be the holder of possessions of a much greater dimension.[9]

Both of Gustav's parents descended from Gregers, the illegitimate son of Birger Jarl; Gustav's father descended from Gregers through his maternal great-grandmother Margareta Karlsdotter, while Gustav's mother descended from him through her father Magnus Karlsson Eka. Additionally, Birgitta Gustafsdotter and Sten Sture (and consequently also Gustav) descended from King Sverker II of Sweden through King Sverker's granddaughter Benedikte Sunesdotter (who was married to Svantepolk Knutsson, son of Duke of Reval).

Resistance against Denmark

Supporting the Sture party

Since the end of the 14th century, Sweden had been a part of the Kalmar Union with Denmark and Norway. The Danish dominance in this union occasionally led to uprisings in Sweden. During Gustav's childhood, parts of the Swedish nobility tried to make Sweden independent. Gustav and his father Erik supported the party of Sten Sture the Younger, regent of Sweden from 1512, and its struggle against the Danish King Christian II. Following the battle of Brännkyrka in 1518, where Sten Sture's troops beat the Danish forces, it was decided that Sten Sture and King Christian would meet in Österhaninge for negotiations. To guarantee the safety of the king, the Swedish side sent six men as hostages to be kept by the Danes for as long as the negotiations lasted. However, Christian did not show up for the negotiations, violated the deal with the Swedish side and took the hostages aboard ships carrying them to Copenhagen. The six members of the kidnapped hostage were Hemming Gadh, Lars Siggesson (Sparre), Jöran Siggesson (Sparre), Olof Ryning, Bengt Nilsson (Färla) – and Gustav Eriksson. Gustav was held in Kalø Castle where he was treated very well after promising he would not make attempts to escape. A reason for this gentle treatment was King Christian's hope to convince the six men to switch sides, and turn against their leader Sten Sture. This strategy was successful regarding all men but Gustav, who stayed loyal to the Sture party.[10]

In 1519, Gustav Eriksson escaped from Kalø. He fled to the Hanseatic city of Lübeck where he arrived on 30 September. How he managed to escape is not certain, but according to a somewhat likely story, he disguised himself as a bullocky. For this, Gustav Eriksson got the nicknames "King Oxtail" and "Gustav Cow Butt", something he indeed disliked. When a swordsman drank to His Majesty "Gustav Cow Butt" in Kalmar in 1547, the swordsman was killed.[11]

While staying in Lübeck, Gustav could hear about developments in his native Sweden. While he was there, Christian II mobilised to attack Sweden in an effort to seize power from Sten Sture and his supporters. In 1520, the forces of King Christian were triumphant. Sten Sture died in March, but some strongholds, including the Swedish capital Stockholm, were still able to withstand the Danish forces. Gustav left Lübeck on a ship, and was put ashore south of Kalmar on 31 May.[12]

It seems Gustav stayed largely inactive during his first months back on Swedish soil. According to some sources, Gustav received an invitation to the coronation of Christian. This was to take place in the newly captured Stockholm in November. Even though King Christian had promised amnesty to his enemies within the Sture party, including Gustav Eriksson, the latter chose to decline the invitation. The coronation took place on 4 November and days of festivities in a friendly spirit followed. When the celebration had lasted a few days, the castle was locked and the former enemies of King Christian were imprisoned. Accusations against the old supporters of Sten Sture regarding heresy were brought forward. The following day the sentences were announced. During the Stockholm Bloodbath, close to 100 people were executed on Stortorget, among them Gustav Eriksson's father, Erik Johansson, and nephew, Joakim Brahe. Gustav himself was at the time staying at Räfsnäs, close to Gripsholm Castle.[13]

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_19512.tif.jpg.webp)

In Dalarna

Gustav Eriksson had reasons to fear for his life and left Räfsnäs. He travelled to the province of Dalarna, in what was then northwestern Sweden. What happened there has been described in Peder Svart's chronicle, which can be described as a strongly biased heroic tale about Gustav Eriksson. The Dalarna adventures of Gustav that could be described as a part of the national heritage of Sweden, can therefore not be verified in a satisfying way. He is supposed to have tried to gather troops among the peasantry in the province, but with little success initially. Being chased by men loyal to king Christian and failing at creating an army to challenge the king, Gustav Eriksson had no other alternative but to flee to Norway. While he made his way from Mora via Lima to Norway, people that had recently turned down Gustav's call for support against the king changed their minds. Representatives of that group caught up with Gustav before he had reached Norway and convinced him to follow them back to Mora. Gustav Eriksson's run towards Norway and back has formed the background to the famous cross-country ski race Vasaloppet.[14]

Swedish War of Liberation

Gustav Eriksson was appointed hövitsman. The rebel force he led grew. In February 1521 it consisted of 400 men, mainly from the area around Lake Siljan. The first big clash in the Dissolution of Kalmar Union that now started, took place at Brunnbäck's Ferry in April, where a rebel army defeated an army loyal to the king. The sacking of the city of Västerås and with it controlling important copper and silver mines gave Gustav Vasa resources and supporters flocked to him. Other parts of Sweden, for example the Götaland provinces of Småland and Västergötland, also saw rebellions. The leading noblemen of Götaland joined Gustav Eriksson's forces and, in Vadstena in August, they declared Gustav regent of Sweden.[15]

The election of Gustav Eriksson as a regent made many Swedish nobles, who had so far stayed loyal to King Christian, switch sides. Some noblemen, still loyal to the king, chose to leave Sweden, while others were killed. As a result, the Swedish Privy Council lost old members who were replaced by supporters of Gustav Eriksson. Most fortified cities and castles were conquered by Gustav's rebels, but the strongholds with the best defences, including Stockholm, were still under Danish control. In 1522, after negotiations between Gustav Eriksson's people and Lübeck, the Hanseatic city joined the war against Denmark. The winter of 1523 saw the joint forces attack the Danish and Norwegian areas of Scania, Halland, Blekinge and Bohuslän. During this winter, Christian II was overthrown and replaced by Frederick I. The new king openly claimed the Swedish throne and had hopes Lübeck would abandon the Swedish rebels. The German city, preferring an independent Sweden to a strong Kalmar Union dominated by Denmark, took advantage of the situation and put pressure on the rebels. The city wanted privileges on future trade as well as guarantees regarding the loans they had granted the rebels. The Privy Council and Gustav Eriksson knew the support from Lübeck was absolutely crucial. As a response, the council decided to appoint Gustav Eriksson king.[16]

Election as king

The ceremonial election of the regent Gustav Eriksson as king of Sweden took place when the leading men of Sweden got together in Strängnäs in June 1523.[17] When the councillors of Sweden had chosen Gustav as king, he met with the two visiting councillors of Lübeck. The German representatives supported the appointment without hesitation and declared it an act of God. Gustav stated he had to bow to what was described as the will of God. In a meeting with the Privy Council, Gustav Eriksson announced his decision to accept. In the following ceremony, led by the deacon of Strängnäs, Laurentius Andreae, Gustav swore the royal oath. The next day, bishops and priests joined Gustav in Roggeborgen where Laurentius Andreae raised the holy sacrament above a kneeling Gustav Eriksson. Flanked by the councillors of Lübeck, Gustav Eriksson was brought to Strängnäs Cathedral where the king sat down in the choir with the Swedish privy councillors on one side, and the Lübeck representatives on the other. After the hymn "Te Deum", Laurentius Andreae proclaimed Gustav Eriksson king of Sweden. He was, however, still not crowned. In 1983, in remembrance of the election of Gustav as Swedish king on 6 June, that date was declared the National Day of Sweden.[18]

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_23935.tif.jpg.webp)

The capture of Stockholm

Shortly after the events of 1523 in Strängnäs, letters patent were issued to Lübeck and its allied Hanseatic cities, who now were freed from tolls when trading in Sweden. An agreement, designed by Lübeck negotiators, was made with the Danish defenders in Stockholm. On 17 June the rebels could enter the capital city. At Midsummer, a grand entrance of king Gustav was arranged at Söderport, the southern gate of Stockholm. Celebrations followed, including a mass of thanksgiving in Storkyrkan (also known as Stockholm Cathedral) led by Peder Jakobsson. Gustav could now install himself in the Tre Kronor palace.[19]

The war ends

Bailiffs, loyal to the old king Christian, were still holding castles in Finland, a part of Sweden at the time. During the summer and fall of 1523 they all surrendered.[20] The next year, on 24 August 1524, Gustav arrived in Malmö in order to reach a settlement with Denmark-Norway and its king Frederick. The Treaty of Malmö (in Swedish: Malmö recess) had both positive and negative sides to it, from king Gustav's perspective. The treaty meant that Denmark-Norway acknowledged the independence of Sweden. The hopes Gustav had carried of winning further provinces (Gotland and Blekinge) were however scuttled. The treaty marked the end of the Swedish War of Liberation.[21]

The Reformation

After Gustav seized power, the previous Archbishop, Gustav Trolle, who at the time held the post of a sort of chancellor, was exiled from the country. Gustav sent a message to Pope Clement VII requesting the acceptance of a new archbishop selected by Gustav himself: Johannes Magnus.

The Pope sent back his decision demanding that the unlawful expulsion of Archbishop Gustav Trolle be rescinded, and that the archbishop be reinstated. Here Sweden's remote geographical location proved to have a marked impact – for the former Archbishop had been allied with Christian, or at least was considered to have been so allied in contemporary Stockholm, and to reinstate him would be close to impossible for Gustav.

The king let the Pope know the impossibility of the request, and the possible results if the Pope persisted, but – for better or worse – the Pope did persist, and refused to accept the king's suggestions of archbishops. At the time, incidentally and for different reasons, there were also four other unoccupied bishop's seats, where the king made suggestions to the Pope about candidates, but the Pope only accepted one of the candidates. Because the Pope refused to budge on the issue of Gustav Trolle, the king, influenced by Lutheran scholar Olaus Petri, in 1531 took it upon himself to appoint yet another archbishop, namely the brother of Olaus, Laurentius Petri. With this royal act, the Pope lost any influence over the Swedish Church.

In the 1520s, the Petri brothers led a campaign for the introduction of Lutheranism. The decade saw many events which can be seen as gradual introductions of Protestantism, for instance the marriage of Olaus Petri – a consecrated priest – and several texts published by him, advocating Lutheran dogmas. A translation of the New Testament had also been published in 1526. After the reformation, a full translation was published in 1540–41, called the Gustav Vasa Bible. However, knowledge of Greek and Hebrew among Swedish clergymen was not sufficient for a translation from the original sources; instead the work followed the German translation by Martin Luther in 1534.

Gustav I's breaking with the Catholic Church is virtually simultaneous with Henry VIII doing the same in England; both kings acted following a similar pattern, i.e., a prolonged confrontation with the Pope culminating with the king deciding to take his own decisions independently of Rome.

Further reign

Gustav encountered resistance from some areas of the country. People from Dalarna rebelled three times in the first ten years of Gustav's reign, as they considered the king to have been too harsh on everyone he perceived as a supporter of the Danish, and as they resented his introduction of Protestantism. Many of those who had helped Gustav in his war against the Danes became involved in these rebellions and paid for this, several of them with their lives.

Peasants in Småland rebelled in 1542, fuelled by grievances over taxes, church reform and confiscation of church bells and vestments. For several months this uprising caused Gustav severe difficulties in the dense forests. The king sent a letter to the people of the province of Dalarna, requesting that they should circulate letters to every Swedish province, stating their support for the king with their troops, and urging every other province to do the same. Gustav got his troops, with whose help – and, not least, with paid German mercenaries – he managed to defeat the rebels in the spring of 1543.

The leader of the rebels, Nils Dacke, has traditionally been seen as a traitor to Sweden. His own letters and proclamations to fellow peasants focused on the suppression of Roman Catholic customs of piety, the King's requisitions of church bells and church plate to be smelted down for money and the general discontent with Gustav's autocratic measures, and the King's letters indicate that Dacke had considerable military success for several months. Historical records state that Nils was seriously wounded during a battle, taking bullet wounds to both legs; if this is true, his survival may have been surprising in view of contemporary medical techniques. Some sources state that Nils was executed by quartering;[22] others that he was reduced to the state of an outlaw after recovering from his wounds, and killed while trying to escape through the woods on the border between Småland and then Danish Blekinge. It is said that his body parts were displayed throughout Sweden as a warning to other would-be rebels; this is uncertain though his head was likely mounted on a pole at Kalmar. Modern Swedish scholarship has toned down criticism of Nils Dacke, sometimes making him into a hero in the vein of Robin Hood, particularly in Småland.

Difficulties with the continuation of the Church also troubled Gustav Vasa. The 1540s saw him imposing death sentences upon both the Petri brothers, as well as his former chancellor Laurentius Andreae. All of them were however granted amnesty, after spending several months in jail. In 1554–1557, he waged an inconclusive war against Ivan the Terrible of Russia.

End of reign

In the late 1550s, Gustav's health declined. When his grave was opened in 1945, an examination of his corpse revealed that he had suffered chronic infections of a leg and in his jaw.

He gave a so-called "last speech" in 1560 to the chancellors, his children and other noblemen, whereby he encouraged them to remain united. On 29 September 1560, Gustav died and was buried (together with three of his wives, while only two are engraved) in the Cathedral of Uppsala.

Legacy

In Sweden, Gustav Vasa is considered to rank among the country's greatest kings, arguably even the most significant ruler in Swedish history. Having ended foreign domination over Sweden, centralized and reorganized the government, cut religious ties to Rome, established the Swedish Church, and founded Sweden's hereditary monarchy, Gustav Vasa holds a place of great prominence in Swedish history and is a central character in Swedish nationalist narratives. He is often described as a founding father of the modern Swedish state, if not of the nation as such. Historians have nonetheless noted the often brutal methods with which he ruled, and his legacy, though clearly of great and lasting importance, is not necessarily viewed in exclusively positive terms.

Many details of Gustav Vasa's historical record are disputed. In 19th-century Swedish history a folklore developed wherein Gustav was supposed to have had many adventures when he liberated Sweden from the Danes. Today most of these stories are considered to have no other foundation than legend and skillful propaganda by Gustav himself during his time. One such story states he was staying at a close friend's farm to rest for one day during his escape from the Danish army. As he was warming himself in the common room, the Danish soldiers got a tip from one of the farm hands that Gustav was in his landlord's farm house. The Danish soldiers burst into the farm house and began searching in the common room for someone that would fit Gustav's description. As one of the soldiers came close to check Gustav Vasa, all of a sudden the landlady took out a bakery spade and started to hit Gustav and scolded him as a "lazy farmboy" and ordered him to go out and work. The Danish soldier found it amusing and did not realise this "lazy farmboy" was in fact Gustav Vasa himself who managed to slip away from danger and escape death. There are many other stories about Gustav's close encounters with death, however it is questionable if any of his adventures really did happen or were dramatised by Gustav himself; regardless of whether they happened or not, his adventures are still told to this day in Sweden.

The memory of Gustav has been honored greatly, resulting in embroidered history books, commemorative coins, and the annual ski event Vasaloppet (the largest ski event in the world with 15,000 participants). The city of Vaasa in Finland was named after the royal house of Vasa in 1606. 18th century playwrights and librettists used his biography as the source for some of their works, including the 1739 Gustavus Vasa by Henry Brooke (the first play banned under the Licensing Act 1737, due to Robert Walpole's belief that the play's villain was a proxy for himself) and the 1770 Gustavo primo re di Svezia. The name Gustavus Vasa was also given to Olaudah Equiano, a prominent Black British abolitionist.[23]

Gustav used to be portrayed on the 1000 kronor note, until he was replaced by Dag Hammarskjöld in June 2016.[24] Gustav has been regarded by some as a power-hungry man who wished to control everything: the Church, the economy, the army and all foreign affairs. But in doing this, he also did manage to unite Sweden, a country that previously had no standardised language, and where individual provinces held a strong regional power. He also laid the foundation for Sweden's professional army that was to make Sweden into a regional superpower in the 17th century.

Gallery

Gustav Vasa had a series of paintings made during his reign. The originals are lost but watercolour reproductions of unknown date remain. These paintings show Gustav's triumphs, showing what Gustav himself considered important to depict.

Part one. Year 1521–23, Outside Stockholm

Part one. Year 1521–23, Outside Stockholm Part two. Year 1525, Inside Stockholm

Part two. Year 1525, Inside Stockholm Part three. Year 1527, Inside and outside Västerås

Part three. Year 1527, Inside and outside Västerås Part four. Year 1542, the Dacke uprising

Part four. Year 1542, the Dacke uprising Part five. Year 1541, in Brömsebro with Christian III of Denmark

Part five. Year 1541, in Brömsebro with Christian III of Denmark

Family

Gustav's first wife was Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535), whom he married on 24 September 1531. They had a son:

- Eric XIV (1533–1577), Duke of Kalmar

On 1 October 1536, he married his second wife, Margareta Leijonhufvud (1514–1551). Their children were:

- John III (Johan III) (1537–1592), Duke of Finland

- Katarina (1539–1610), wife of Edzard II, Count of Ostfriesland. A grandmother of Anna Maria of Ostfriesland and great-grandmother of Adolf Frederick II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

- Cecilia (1540–1627), wife of Christopher II, Margrave of Baden-Rodemachern

- Magnus (1542–1595), Duke of Östergötland

- Carl (1544)

- Anna (1545–1610), wife of George John I, Count Palatine of Veldenz

- Sten (1546–1547)

- Sofia (1547–1611), wife of Duke Magnus II of Saxe-Lauenburg

- Elisabet (1549–1598), wife of Christopher, Duke of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch

- Charles IX (Carl IX) (1550–1611), Duke of Södermanland

At Vadstena Castle on 22 August 1552, he married his third wife, Katarina Stenbock (1535–1621).

See also

- City of Vasa

- Early Vasa era

- Vasa

- Vasaloppet

Notes

- Gustav's gravestone gives his year of birth as 1485, and according to his son Charles IX he had been born in 1488. His nephew Per Brahe gives 1495 as Gustav's year of birth, and historian Erik Göransson Tegel the year 1490. Brahe and Tegel agree that Gustav was born on Ascension Thursday, 12 May, and these days coincided in 1491 and 1496.

- "Sweden". World Statesmen. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- Anastacia Sampson. "Swedish Monarchy – Gustav Vasa". sweden.org.za. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Magne Njåstad. "Gustav 1 Vasa". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Gunilla Petersén, "From the History of the Royal Court Orchestra 1526–2007"

- "Gustav Vasa - Uppslagsverk - NE.se".

- Brev av Gustav Vasa (Letters of Gustav Vasa) edited by Nils Edén, Norstedts, Stockholm, 1917

- Larsson 2005, p. 21.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 25ff.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 38ff.

- Larsson 2005, p. 42.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 43–45.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 45ff.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 52ff.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 59ff.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 67ff.

- Peterson, Gary Dean (1 January 2007). Warrior Kings of Sweden: The Rise of an Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. McFarland. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-7864-2873-1. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 74ff.

- Larsson 2005, pp. 76ff.

- Larsson 2005, p. 98.

- Larsson 2005, p. 108.

- Dackeland/Gustav Vasa – Landsfader eller tyrann? by Lars-Olof Larsson.

- "Olaudah Equiano (c.1745 - 1797)". History. BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- http://www.riksbank.se/sv/Sedlar--mynt/Sedlar/Nya-sedlar/1000-kronorssedel/ Archived 15 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Official Swedish National Bank entry on the new 1000 SEK note

Other sources

- Åberg, Alf (1996) Gustav Vasa 500 år / The official anniversary book (Stockholm: Norstedts) ISBN 978-9119611628

- Larsson, Lars-Olof (2005) Gustav Vasa – Landsfader eller tyrann? (Stockholm: Prima) ISBN 978-9151839042

- Nieritz, Gustav (2018) Gustavus Vasa, or King and Peasant: With a Historic Sketch and Notes (Forgotten Books ) ISBN 978-0656337927

- Roberts, Michael (1968) The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden 1523–1611 (Cambridge University Press) ISBN 978-0521311823

- Watson, Paul Barron (2011) The Swedish Revolution under Gustavus Vasa (British Library, historical print editions) ISBN 978-1241540043

External links

- The Rapier of Gustav Vasa, King of Sweden (myArmoury.com article)

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.