Hamites

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races which was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery.[1][2][3][4] The term was originally borrowed from the Book of Genesis, where it is used for the descendants of Ham, son of Noah.

The term was originally used in contrast to the other two proposed divisions of mankind based on the story of Noah: Semites and Japhetites. The appellation Hamitic was applied to the Berber, Cushitic, and Egyptian branches of the Afroasiatic language family, which, together with the Semitic branch, was thus formerly labelled "Hamito-Semitic".[5] However, since the three Hamitic branches have not been shown to form an exclusive (monophyletic) phylogenetic unit of their own, separate from other Afroasiatic languages, linguists no longer use the term in this sense. Each of these branches is instead now regarded as an independent subgroup of the larger Afroasiatic family.[6]

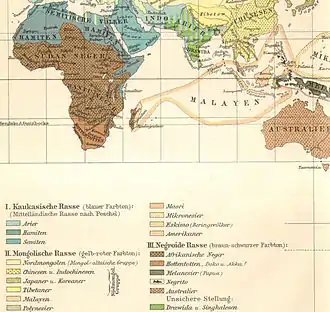

Beginning in the 19th century, scholars generally classified the Hamitic race as a subgroup of the Caucasian race, alongside the Aryan race and the Semitic[7][8] – thus grouping the non-Semitic populations native to North Africa and the Horn of Africa, including the Ancient Egyptians.[4] According to the Hamitic theory, this "Hamitic race" was superior to or more advanced than the "Negroid" populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. In its most extreme form, in the writings of C. G. Seligman, this theory asserted that virtually all significant achievements in African history were the work of "Hamites".

Since the 1960s the Hamitic hypothesis, along with other theories of "race science", has become entirely discredited in science.[9]: 10

History of the concept

The "Curse of Ham"

'_(11204692506).jpg.webp)

The term Hamitic originally referred to the peoples said to be descended from Ham, one of the Sons of Noah according to the Bible. According to the Book of Genesis, after Noah became drunk and Ham dishonored his father, upon awakening Noah pronounced a curse on Ham's youngest son, Canaan, stating that his offspring would be the "servants of servants". Of Ham's four sons, Canaan fathered the Canaanites, while Mizraim fathered the Egyptians, Cush the Cushites, and Phut the Libyans.[10]

During the Middle Ages, Jews and Christians considered Ham to be the ancestor of all Africans. Noah's curse on Canaan as described in Genesis began to be interpreted by some theologians as having caused visible racial characteristics in all of Ham's offspring, notably black skin. In a passage unrelated to the curse on Canaan, the sixth-century Babylonian Talmud says that Ham and his descendants were cursed with black skin, which modern scholars have interpreted as an etiological myth for skin color. [8][11]: 522 Later, Western and Islamic traders and slave owners used the concept of the "Curse of Ham" to justify the enslaving of Africans.[12][8]: 522 [11]

A significant change in Western views on Africans came about when Napoleon's 1798 invasion of Egypt drew attention to the impressive achievements of Ancient Egypt, which could hardly be reconciled with the theory of Africans being inferior or cursed. In consequence, some 19th century theologians emphasized that the biblical Noah restricted his curse to the offspring of Ham's youngest son Canaan, while Ham's son Mizraim, the ancestor of the Egyptians, was not cursed.[8]: 526–7

Constructing the "Hamitic race"

Following the Age of Enlightenment, many Western scholars were no longer satisfied with the biblical account of the early history of mankind, but started to develop faith-independent theories. These theories were developed in a historical situation where most Western nations were still profiting from the enslavement of Africans.[8]: 524 In this context, many of the works published on Egypt after Napoleon's expedition "seemed to have had as their main purpose an attempt to prove in some way that the Egyptians were not Negroes",[8]: 525 thus separating the high civilization of Ancient Egypt from what they wanted to see as an inferior race. Authors such as W. G. Browne, whose Travels in Africa, Egypt and Syria was published in 1806, laid the "seeds for the new Hamitic myth that was to emerge in the very near future", insisting that the Egyptians were white.[8]: 526

In the mid-19th century, the term Hamitic acquired a new anthropological meaning, as scholars asserted that they could discern a "Hamitic race" that was distinct from the "Negroid" populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. Richard Lepsius would coin the appellation Hamitic to denote the languages which are now seen as belonging to the Berber, Cushitic and Egyptian branches of the Afroasiatic family.[5]

"Perhaps because slavery was both still legal and profitable in the United States ... there arose an American school of anthropology which attempted to prove scientifically that the Egyptian was a Caucasian, far removed from the inferior Negro".[8]: 526 Through craniometry conducted on thousands of human skulls, Samuel George Morton argued that the differences between the races were too broad to have stemmed from a single common ancestor, but were instead consistent with separate racial origins. In his Crania Aegyptiaca (1844), Morton analyzed over a hundred intact crania gathered from the Nile Valley, and concluded that the ancient Egyptians were racially akin to Europeans. His conclusions would establish the foundation for the American School of anthropology, and would also influence proponents of polygenism.[13]

Development of the Hamitic hypothesis

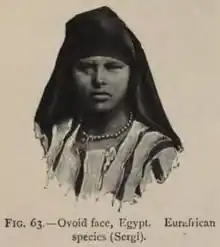

In his influential The Mediterranean Race (1901), the anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi argued that the Mediterranean race had likely originated from a common ancestral stock that evolved in the Sahara region in Africa, and which later spread from there to populate North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and the circum-Mediterranean region.[14] According to Sergi, the Hamites themselves constituted a Mediterranean variety, and one situated close to the cradle of the stock.[15] He added that the Mediterranean race "in its external characters is a brown human variety, neither white nor negroid, but pure in its elements, that is to say not a product of the mixture of Whites with Negroes or negroid peoples."[16] Sergi explained this taxonomy as inspired by an understanding of "the morphology of the skull as revealing those internal physical characters of human stocks which remain constant through long ages and at far remote spots[...] As a zoologist can recognise the character of an animal species or variety belonging to any region of the globe or any period of time, so also should an anthropologist if he follows the same method of investigating the morphological characters of the skull[...] This method has guided me in my investigations into the present problem and has given me unexpected results which were often afterwards confirmed by archaeology or history."[17]

The Hamitic hypothesis reached its apogee in the work of C. G. Seligman, who argued in his book The Races of Africa (1930) that:

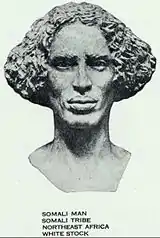

Apart from relatively late Semitic influence... the civilizations of Africa are the civilizations of the Hamites, its history is the record of these peoples and of their interaction with the two other African stocks, the Negro and the Bushmen, whether this influence was exerted by highly civilized Egyptians or by such wider pastoralists as are represented at the present day by the Beja and Somali... The incoming Hamites were pastoral Caucasians – arriving wave after wave – better armed as well as quicker witted than the dark agricultural Negroes."[18][8]: 521

Seligman asserted that the Negro race was essentially static and agricultural, and that the wandering "pastoral Hamitic" had introduced most of the advanced features found in central African cultures, including metal working, irrigation and complex social structures.[19][8]: 530 Despite criticism, Seligman kept his thesis unchanged in new editions of his book into the 1960s.[8]: 530

Hamitic hypotheses operated in West Africa as well, and they changed greatly over time.[20]

With the demise of the concept of Hamitic languages, the notion of a definable "Hamite" racial and linguistic entity was heavily criticised. In 1974, writing about the African Great Lakes region, Christopher Ehret described the Hamitic hypothesis as the view that "almost everything more un-'primitive', sophisticated or more elaborate in East Africa [was] brought by culturally and politically dominant Hamites, immigrants from the North into East Africa, who were at least part Caucasoid in physical ancestry".[21] He called this a "monothematic" model, which was "romantic, but unlikely" and "[had] been all but discarded, and rightly so". He further argued that there were a "multiplicity and variety" of contacts and influences passing between various peoples in Africa over time, something that he suggested the "one-directional" Hamitic model obscured.[21]

Subdivisions and physical traits

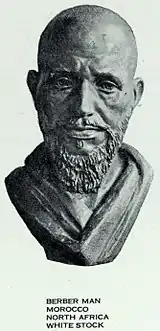

Sergi outlined the constituent Hamitic physical types, which would form the basis for the work of later writers such as Carleton Coon and C. G. Seligman. In his book The Mediterranean Race (1901), he wrote that there was a distinct Hamitic ancestral stock, which could be divided into two subgroups: the Western Hamites (or Northern Hamites, comprising the Berbers of the Mediterranean, Atlantic and Sahara, Tibbu, Fula, and extinct Guanches), and the Eastern Hamites (or Ethiopids, comprising Ancient and Modern Egyptians (but not the Arabs in Egypt), Nubians, Beja, Abyssinians, Galla, Danakil, Somalis, Masai, Bahima and Watusi).[22][23]

According to Coon, typical Hamitic physical traits included narrow facial features; an orthognathous visage; light brown to dark brown skin tone; wavy, curly or straight hair; thick to thin lips without eversion; and a dolichocephalic to mesocephalic cranial index.[24]

According to Ashley Montagu "Among both the Northern and Eastern Hamites are to be found some of the most beautiful types of humanity."[4]

"Hamiticised Negroes"

In the African Great Lakes region, Europeans based the various migration theories of Hamitic provenance in part on the long-held oral traditions of local populations such as the Tutsi and Hima (Bahima, Wahuma or Mhuma). These groups asserted that their founders were "white" migrants from the north (interpreted as the Horn of Africa and/or North Africa), who subsequently "lost" their original language, culture, and much of their physiognomy as they intermarried with the local Bantus. Explorer J.H. Speke recorded one such account from a Wahuma governor in his book, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile.[25] According to Augustus Henry Keane, the Hima King Mutesa I also claimed Oromo (Galla) ancestors and still reportedly spoke an Oromo idiom, though that language had long since died out elsewhere in the region.[26] The missionary R. W. Felkin, who had met the ruler, remarked that Mutesa "had lost the pure Hamitic features through admixture of Negro blood, but still retained sufficient characteristics to prevent all doubt as to his origin".[27] Thus, Keane would suggest that the original Hamitic migrants to the Great Lakes had "gradually blended with the aborigines in a new and superior nationality of Bantu speech".[26]

Speke believed that his explorations uncovered the link between "civilized" North Africa and "primitive" central Africa. Describing the Ugandan Kingdom of Buganda, he argued that its "barbaric civilization" had arisen from a nomadic pastoralist race who had migrated from the north and was related to the Hamitic Oromo (Galla) of Ethiopia.[8]: 528 In his Theory of Conquest of Inferior by Superior Races (1863), Speke would also attempt to outline how the Empire of Kitara in the African Great Lakes region may have been established by a Hamitic founding dynasty.[28] These ideas, under the rubric of science, provided the basis for some Europeans asserting that the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu. In spite of both groups being Bantu-speaking, Speke thought that the Tutsi had experienced some "Hamitic" influence, partly based on their facial features being comparatively more narrow than those of the Hutu. Later writers followed Speke in arguing that the Tutsis had originally migrated into the lacustrine region as pastoralists and had established themselves as the dominant group, having lost their language as they assimilated to Bantu culture.[29]

Seligman and other early scholars believed that, in the African Great Lakes and parts of Central Africa, invading Hamites from North Africa and the Horn of Africa had mixed with local "Negro" women to produce several hybrid "Hamiticised Negro" populations. The "Hamiticised Negroes" were divided into three groups according to language and degree of Hamitic influence: the "Negro-Hamites" or "Half-Hamites" (such as the Maasai, Nandi and Turkana), the Nilotes (such as the Shilluk and Nuer), and the Bantus (such as the Hima and Tutsi). Seligman would explain this Hamitic influence through both demic diffusion and cultural transmission:

At first the Hamites, or at least their aristocracy, would endeavour to marry Hamitic women, but it cannot have been long before a series of peoples combining Negro and Hamitic blood arose; these, superior to the pure Negro, would be regarded as inferior to the next incoming wave of Hamites and be pushed further inland to play the part of an incoming aristocracy vis-a-vis the Negroes on whom they impinged... The end result of one series of such combinations is to be seen in the Masai [sic], the other in the Baganda, while an even more striking result is offered by the symbiosis of the Bahima of Ankole and the Bahiru [sic].[30][19]

European colonial powers in Africa were influenced by the Hamitic hypothesis in their policies during the twentieth century. For instance, in Rwanda, German and Belgian officials in the colonial period displayed preferential attitudes toward the Tutsis over the Hutu. Some scholars argued that this bias was a significant factor that contributed to the 1994 Rwandan genocide of the Tutsis by the Hutus.[31][32]

African-American reception

African-American scholars were initially ambivalent about the Hamitic hypothesis. Because Sergi's theory proposed that the superior Mediterranean race had originated in Africa, some African-American writers believed that they could appropriate the Hamitic hypothesis to challenge Nordicist claims about the superiority of the white Nordic race. The latter "Nordic" concept was promoted by certain writers, such as eugenicist Madison Grant. According to Yaacov Shavit, this generated "radical Afrocentric theory, which followed the path of European racial doctrines". Writers who insisted that the Nordics were the purest representatives of the Aryan race indirectly encouraged "the transformation of the Hamitic race into the black race, and the resemblance it draws between the different branches of black forms in Asia and Africa."[33]

In response, historians published in the Journal of Negro History stressed the cross-fertilization of cultures between Africa and Europe: for instance, George Wells Parker adopted Sergi's view that the "civilizing" race had originated in Africa itself.[34][35] Similarly, black pride groups appropriated the concept of Hamitic identity for their own purposes. Parker founded the Hamitic League of the World in 1917 to "inspire the Negro with new hopes; to make him openly proud of his race and of its great contributions to the religious development and civilization of mankind." He argued that "fifty years ago one would not have dreamed that science would defend the fact that Asia was the home of the black races as well as Africa, yet it has done just that thing."[36]

Timothy Drew and Elijah Muhammad developed from this the concept of the "Asiatic Blackman."[37] Many other authors followed the argument that civilization had originated in Hamitic Ethiopia, a view that became intermingled with biblical imagery. The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) (1920) believed that Ethiopians were the "mother race". The Nation of Islam asserted that the superior black race originated with the lost tribe of Shabazz, which originally possessed "fine features and straight hair", but which migrated into Central Africa, lost its religion, and declined into a barbaric "jungle life".[33][38][39]

Afrocentric writers considered the Hamitic hypothesis to be divisive since it asserted the inferiority of "Negroid" peoples. W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) thus argued that "the term Hamite under which millions of Negroes have been characteristically transferred to the white race by some eager scientists" was a tool to create "false writing on Africa".[40] According to Du Bois, "Livingstone, Stanley, and others were struck with the Egyptian features of many of the tribes of Africa, and this is true of many of the peoples between Central Africa and Egypt, so that some students have tried to invent a 'Hamitic' race to account for them—an entirely unnecessary hypothesis."[41]

See also

- Afroasiatic languages

- Generations of Noah

- Japhetites

- Semites

References

- For the model of dividing humanity into races, see American Association of Physical Anthropologists (27 March 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

Instead, the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination.

- For the Hamitic theory, see Benesch, Klaus; Fabre, Geneviève (2004). African Diasporas in the New and Old Worlds: Consciousness and Imagination. Rodopi. p. 269. ISBN 978-90-420-0870-0.

- Also specifically for the Hamitic theory: Howe, Stephen (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. Verso. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-85984-228-7.

- Ashley, Montagu (1960). An Introduction to Physical Anthropology – Third Edition. Charles C. Thomas Publisher. p. 456.

- Allan, Keith (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. OUP Oxford. p. 275. ISBN 978-0199585847. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Everett Welmers, William (1974). African Language Structures. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0520022102. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition, 1885-90, T11, p.476.

- Sanders, Edith R. (October 1969). "The Hamitic Hypothesis; Its Origin and Functions in Time Perspective". The Journal of African History. 10 (4): 521–532. doi:10.1017/S0021853700009683. ISSN 1469-5138. JSTOR 179896. S2CID 162920355.

- de Luna, Kathryn M. (25 November 2014). "Bantu Expansion" (PDF). Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199846733-0165. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Evans, William M (February 1980), "From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Guinea: The Strange Odyssey of the 'Sons of Ham'", American Historical Review, 85 (1): 15–43, doi:10.2307/1853423, JSTOR 1853423.

- Goldenberg, David (1997). "The Curse of Ham: A Case of Rabbinic Racism?". Struggles in the Promised Land. pp. 21–51.

- Swift, John N; Mammoser, Gigen (Fall 2009), "Out of the Realm of Superstition: Chesnutt's 'Dave's Neckliss' and the Curse of Ham", American Literary Realism, 42 (1): 3, doi:10.1353/alr.0.0033, S2CID 162193875.

- Robinson, Michael F. (2016). The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0199978502. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008), pp.42-43.

- Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (Forgotten Books), pp.39-44.

- Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008), p.250.

- Giuseppe Sergi, The Mediterranean Race: A Study of the Origin of European Peoples, (Forgotten Books), p.36.

- Seligman, CG (1930), The Races of Africa, London, p. 96.

- Rigby, Peter (1996), African Images, Berg, p. 68

- Examples from Nigeria: Zachernuk, Philip (1994). "Of Origins and Colonial Order: Southern Nigerians and the 'Hamitic Hypothesis' c. 1870–1970". Journal of African History. 35 (3): 427–55. doi:10.1017/s0021853700026785. JSTOR 182643. S2CID 162548206.

- Ehret, C, Ethiopians and East Africans: The Problem of Contacts, East African Pub. House, 1974, p.8.

- Sergi, Giuseppe (1901), The Mediterranean Race, London: W Scott, p. 41.

- The list of peoples given according to a summary of Sergi's book in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Coon, Carleton (1939). The Races of Europe (PDF). The Macmillan Company. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Speke, John Hanning (1868), Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, Harper & bros, p. 514.

- Keane, A.H. (1899). Man, Past and Present. p. 90.

- Boyd, James Penny (1889). Stanley in Africa: The Wonderful Discoveries and Thrilling Adventures of the Great African Explorer, and Other Travelers, Pioneers and Missionaries. Stanley Publishing Company. p. 722. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Speke 1863, p. 247.

- Gourevitch 1998.

- Seligman, Charles Gabriel (1930). The Races of Africa (PDF). Thornton Butterworth, Ltd. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Gatwa, Tharcisse (2005), The Churches and Ethnic Ideology in the Rwandan Crises, 1900–1994, OCMS, p. 65.

- Taylor, Christopher Charles (1999), Sacrifice as Terror: the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, Berg, p. 55.

- Shavit 2001, pp. 26, 193.

- Parker, George Wells (1917), "The African Origin of the Grecian Civilization", Journal of Negro History: 334–44.

- Shavit 2001, p. 41.

- Parker, George Wells (1978) [Omaha, 1918], Children of the Sun (reprint ed.), Baltimore: Black Classic Press.

- Deutsch, Nathaniel (October 2001), "'The Asiatic Black Man': An African American Orientalism?", Journal of Asian American Studies, 4 (3): 193–208, doi:10.1353/jaas.2001.0029, S2CID 145051546.

- Ogbar, Jeffrey Ogbonna Green (2005), Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 144.

- X, Malcolm (1989), The End of White World Supremacy: Four Speeches, Arcade, p. 46.

- Du Bois, William E. B. (2000), Keita, Maghan (ed.), Race and the Writing of History: Riddling the Sphinx, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 78.

- Du Bois, William E. B. (1947). The World and Africa: An Inquiry Into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History. New York: Viking Press. p. 169.

Bibliography

- Hamitic theory

- Seligman, CG (1930), The Races of Africa, London, p. 96.

- Sergi, Giuseppe (1901), The Mediterranean Race, London: W Scott, p. 41.

- Speke, JH (1863), Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile, London: Blackwoods.

- Other

- Gourevitch, Philip (1998), We Wish to Inform You that Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Robinson, Michael F. (2016), The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent, Oxford.

- Rohrbacher, Peter (2002), Die Geschichte des Hamiten-Mythos, Wien: Afro-Pub.

- Shavit, Yaacov (2001), History in Black: African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past, Routledge.