Hans-Hermann Hoppe

Hans-Hermann Hoppe (/ˈhɒpə/;[5] German: [ˈhɔpə]; born 2 September 1949) is a German-American economist of the Austrian School, philosopher and political theorist.[6][7][8] He is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), Senior Fellow of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, and the founder and president of the Property and Freedom Society.[9][10]

Hans-Hermann Hoppe | |

|---|---|

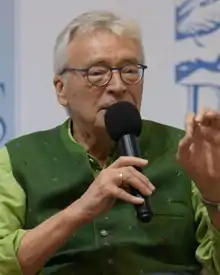

Hoppe in 2022 | |

| Born | 2 September 1949 Peine, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Movement | Anarcho-capitalism Cultural conservatism Paleolibertarianism |

| Spouse | Gülçin Imre Hoppe[1] |

| Institutions | Business school of University of Nevada, Las Vegas Mises Institute Property and Freedom Society |

| Field | |

| School or tradition | Austrian School Continental philosophy |

| Alma mater | Goethe University Frankfurt |

| Influences | |

| Contributions | Argumentation ethics Libertarian critique of democracy |

| Awards | The Gary G. Schlarbaum Prize (2006)[2] Franz Cuhel Memorial Prize (Prague Conference on Political Economy 2009)[3][4] |

| Website | http://www.hanshoppe.com |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarianism in the United States |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcho-capitalism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Austrian School |

|---|

|

|

|

Hoppe identifies as an austro-libertarian[11][12] and anarcho-capitalist, and has written extensively in opposition to democracy in his book Democracy: The God That Failed.[13]

Life and work

Hoppe was born in Peine, West Germany, did undergraduate studies at Universität des Saarlandes[14] and received his MA and PhD degrees from Goethe University Frankfurt.[10] He studied under Jürgen Habermas, a leading German intellectual of the post-WWII era, but gradually came to reject Habermas's ideas, and European leftism generally, regarding them as "intellectually barren and morally bankrupt."[15]

He was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, from 1976 to 1978 and earned his habilitation in Foundations of Sociology and Economics from the University of Frankfurt in 1981. From 1986[16] until his retirement in 2008,[3] Hoppe was a professor in the School of Business at University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Mises Institute, the publisher of much of his work, and was editor of various Mises Institute periodicals.[17]

Hoppe has stated that Murray Rothbard was his "principal teacher, mentor and master".[3] After reading Rothbard's books and being converted to a Rothbardian political position, Hoppe moved from Germany to New York City to be with Rothbard, and then followed Rothbard to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, "working and living side-by-side with him, in constant and immediate personal contact." According to Hoppe, from 1985 until Rothbard's 1995 death, Hoppe considered Rothbard his "dearest fatherly friend".[18] Hoppe was also intimate friends with Ludwig von Mises.[19]

Hoppe resides in Turkey with his wife Gülçin Imre Hoppe, an Austrian school economist.[9][20]

Property and Freedom Society

In 2006, Hoppe founded The Property and Freedom Society ("PFS") as a reaction against the Milton Friedman-influenced Mont Pelerin Society, which he has derided as "socialist". On the fifth anniversary of PFS, Hoppe reflected on its goals:[21]

On the one hand, positively, it was to explain and elucidate the legal, economic, cognitive and cultural requirements and features of a free, state-less natural order. On the other hand, negatively, it was to unmask the State and showcase it for what it really is: an institution run by gangs of murderers, plunderers and thieves, surrounded by willing executioners, propagandists, sycophants, crooks, liars, clowns, charlatans, dupes and useful idiots – an institution that dirties and taints everything it touches.

Hoppe was criticized for inviting white nationalist speakers such as Jared Taylor, and neo-Nazi Richard B. Spencer, to speak at the PFS.[22]

Creation of the Mises Institute

As a result of the economic works of Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Murray Rothbard, Ludwig von Mises, and other Austrian economists, the Mises Institute was founded in 1982 by Lew Rockwell, Burton Blumert, and Murray Rothbard,[23] following a split between the Cato Institute and Rothbard, who had been one of the founders of the Cato Institute. [24]

The Mises Institute has offered thousands of free books written by Hans Hermann Hoppe, Ludwig Von Mises, Murray Rothbard, and other prominent economists in e-book and audiobook format.[25] It has designed a section for beginners that summarizes the main concepts in thirty minutes for those unfamiliar with the concepts of Austrian Economics.[26] The Mises Institute also offers a graduate school program.[27]

Argumentation ethics

In the September 1988 issue of Liberty,[28] Hoppe attempted to establish an a priori and value-neutral justification for libertarian ethics by devising a new theory which he named argumentation ethics.[29] Hoppe asserted that any argument which in any respect purports to contradict libertarian principles is logically incoherent.[30]

Hoppe argued that, in the course of having an argument about politics (or indeed any subject), people assume certain norms of argumentation, including a prohibition on initiating violence. Hoppe then extrapolated this argument to political life in general, arguing that the norms governing argumentation should apply in all political contexts. Hoppe claimed that, of all political philosophies, only anarcho-capitalist libertarianism prohibits the initiation of aggressive violence (the non-aggression principle); therefore, any argument for any political philosophy other than anarcho-capitalist libertarianism is logically incoherent.

Reception

In the following issue, Liberty published comments by ten libertarians,[31] followed by a rejoinder from Hoppe.[29] In his comment for Liberty, Hoppe's friend and Mises Institute supervisor Murray Rothbard wrote that Hoppe's theory was "a dazzling breakthrough for political philosophy in general and for libertarianism in particular" and that Hoppe "has managed to transcend the famous is/ought, fact/value dichotomy that has plagued philosophy since the days of the Scholastics, and that had brought modern libertarianism into a tiresome deadlock".[29] However, the majority of Hoppe's colleagues surveyed by Liberty rejected his theory. In his response, Hoppe derided his critics as "utilitarians".[29]

Later, attorney and Mises Institute adjunct scholar Stephan Kinsella also defended Hoppe's argument,[32] while Mises Institute economists Bob Murphy and Gene Callahan rejected Hoppe's argument.[33] David Osterfeld, an adjunct scholar at the Mises Institute, agreed with most of Hoppe's argument in an essay, while raising a number of objections, to which Hoppe subsequently responded.[34]

Mises Institute Senior Fellow Roderick T. Long stated that Hoppe's a priori formulation of libertarianism denied the fundamental principle of Misesean praxeology. On the issue of utilitarianism, Long wrote, "Hoppe's argument, if it worked, would commit us to recognizing and respecting libertarian rights regardless of what our goals are – but as a praxeologist, I have trouble seeing how any practical requirement can be justified apart from a means-end structure."[35] Long reconstructed Hoppe's argument in deductively valid form, specifying four premises on whose truth the argument's soundness depends, and showed that each premise is either uncertain, doubtful, or clearly false. Long summarized his views by stating:

I don't think there's any reason to reject out of hand the kind of argument that Hoppe tries to give; on the contrary, the idea that there might be some deep connection between libertarian rights and the requirements of rational discourse is one I find attractive and eminently plausible. [...] But I am not convinced that the specific argument Hoppe gives us is successful.[35]

Libertarian philosopher Jason Brennan rejected Hoppe's argument, saying:

For the sake of argument, on Hoppe's behalf, grant that by saying "I propose such and such," I take myself to have certain rights over myself. I take myself to have some sort of right to say, "I propose such and such." I also take you to have some sort of right to control over your own mind and body, to control what you believe. (Nota bene: I don't think Hoppe can even get this far, but I'm granting him this for the sake of argument.) All I need to avoid a performative contradiction is for me to have a liberty right to say, "I propose such and such." I need not presuppose I have a claim right to say "I propose such and such." Instead, at most, I presuppose that it's permissible for me to say, "I propose such and such." I also at most presuppose that you have a liberty right to believe what I say. I do not need to presuppose that you have a claim right to believe what I say. However, libertarian self-ownership theory consists of claim rights [...] Hoppe's argument illicitly conflates a liberty right with a claim right, and so fails.[36]

Another critic argued that Hoppe had not provided any non-circular reasons why we "have to regard moral values as something that must be regarded as being established through (consensual) argument instead of 'mere' subjective preferences for situations turning out in certain ways". In other words, the theory relies "on the existence [of] certain intuitions, the acceptance of which cannot itself be the result of 'value-free' reasoning."[37]

Views on democracy

In 2001, Hoppe published Democracy: The God That Failed which examines various social and economic phenomena which, Hoppe argues, are problems caused by democratic forms of government. He attributes democracy's failures to pressure groups which seek to increase government expenditures and regulations. Hoppe proposes alternatives and remedies, including secession, decentralization of government, and "complete freedom of contract, occupation, trade and migration".[38] Hoppe argues that monarchy would preserve individual liberty more effectively than democracy.[13]

In 2013, Hoppe reflected on the relationship between democracy and the arts and concluded that "democracy leads to the subversion and ultimately disappearance of the notion of beauty and universal standards of beauty. Beauty is swamped and submerged by so-called 'modern art'."[39]

Walter Block, a colleague of Hoppe's at the Mises Institute, asserts that Hoppe's arguments shed light "on historical occurrences, from wars to poverty to inflation to interest rates to crime". Block notes that while Hoppe concedes that 21st-century democracies are more prosperous than the monarchies of old, Hoppe argues that if nobles and kings replaced today's political leaders, their ability to take a long-term view of a country's well-being would "improve matters". Block also shared what he called minor criticisms of Hoppe's theses regarding time preferences, immigration and the gap between libertarianism and conservatism.[40]

Alberto Benegas-Lynch Jr. criticized Hoppe's thesis that monarchy is preferable to democracy.[41] A Professor of Economics at the University of Buenos Aires,[42] Benegas-Lynch provided empirical evidence demonstrating that modern monarchies tend to be far poorer than modern democracies. In response, Hoppe argued that those monarchies were poorer than democracies not because of intrinsic features of these political systems, but because the monarchies used on the study, mostly African countries, compared to the democracies, mostly European countries, led to a distortion in the study.[43] The degree of time preference of a democracy in the present will be lower than a democracy of the past, and even lower in a democracy in the future. In order for a study to be consistent comparing both types of government, one needs to eliminate as much variables as possible, like cultural differences, sex differences, time differences, so on. [41] Hoppe argues that this lack of proper elimination of variables led to distortions in B-L’s study when comparing democracies in Europe and monarchies in Africa.

Criticism

Expulsion of homosexuals and dissidents

His belief in the right of property owners to establish libertarian communities that engage in racial discrimination, and his assertion that communities could establish exclusive criteria for admission and acceptance, have proven particularly divisive.[44][45]

In Democracy Hoppe describes a fully libertarian society of "covenant communities" made up of residents who have signed an agreement defining the nature of that community. He writes that "There would be little or no 'tolerance' and 'openmindedness' so dear to left-libertarians. Instead, one would be on the right path toward restoring the freedom of association and exclusion implied in the institution of private property". He argues that towns and villages could have warning signs saying "no beggars, bums, or homeless, but also no homosexuals, drug users, Jews, Muslims, Germans, or Zulus".[46][47]

Hoppe also makes plain that he believes that practicing certain forms of discrimination, including the physical removal of people whose lifestyle is deemed incompatible with the purpose of establishing certain communities, is completely compatible with his system.

Hoppe writes:

In a covenant concluded among proprietor and community tenants for the purpose of protecting their private property, no such thing as a right to free (unlimited) speech exists, . . . naturally no one is permitted to advocate ideas contrary to the very purpose of the covenant of preserving and protecting private property, such as democracy and communism. There can be no tolerance toward democrats and communists in a libertarian social order. They will have to be physically separated and expelled from society. Likewise, in a covenant founded for the purpose of protecting family and kin, there can be no tolerance toward those habitually promoting lifestyles incompatible with this goal. They – the advocates of alternative, non-family and kin-centered lifestyles such as, for instance, individual hedonism, parasitism, nature-environment worship, homosexuality, or communism – will have to be physically removed from society, too, if one is to maintain a libertarian order.[44]

Commenting on this passage, Martin Snyder of the American Association of University Professors said Hoppe's words will disturb "[t]hose with a better memory than Hoppe for segregation, apartheid, internment facilities and concentration camps, for yellow stars and pink triangles".[48] Hoppe also provoked controversy by calling homosexuality a "perversity or abnormality" analogous to pedophilia, drug use, pornography, polygamy and obscenity.[49]

Walter Block wrote that Hoppe's statement calling for the physical removal of homosexuals from a libertarian political community was "exceedingly difficult to reconcile with libertarianism." Block argues that "it is entirely possible that some areas of the country, parts of Gotham and San Francisco for example, will require this practice, and ban, entirely, heterosexuality. If this is done through contract, private property rights, restrictive covenants, it will be entirely compatible with the libertarian legal code."[50]

Support for immigration restrictions and critiques

Although a self-described anarcho-capitalist who favors abolishing the nation-state, Hoppe also garners controversy due to his support for governmental enforcement of immigration laws, which critics argue is at odds with libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism.[51][22] Hoppe argues that as long as states exist, they should impose some restrictions on immigration. He has equated free immigration to "forced integration" which violates the rights of native peoples, since if land were privately owned, immigration would not be unhindered but would only occur with the consent of private property owners.[52]

Hoppe's Mises Institute colleague Walter Block has characterized Hoppe as an "anti-open immigration activist" who argues that, though all public property is "stolen" by the state from taxpayers, "the state compounds the injustice when it allows immigrants to use [public] property, thus further "invading" the private property rights of the original owners".[53] However, Block rejects Hoppe's views as incompatible with libertarianism. He argues that Hoppe's logic implies that flagrantly unlibertarian laws such as regulations on prostitution and drug use "could be defended on the basis that many tax-paying property owners would not want such behavior on their own private property".[54] Another libertarian author, Simon Guenzl, writing for Libertarian Papers argues that: "supporting a legitimate role for the state as an immigration gatekeeper is inconsistent with Rothbardian and Hoppean libertarian anarchism, as well as with the associated strategy of advocating always and in every instance reductions in the state's role in society."[51]

In terms of specific immigration restrictions, Hoppe argued that an appropriate policy will require immigrants to the United States to display proficiency in English in addition to "superior (above-average) intellectual performance and character structure as well as a compatible system of values".[55] He suggested that these criteria would lead to a "systematic pro-European immigration bias". Jacob Hornberger of the Future of Freedom Foundation argued that the immigration test Hoppe advocated would probably be prejudiced against Latin American immigrants to the United States.[56]

Remarks about homosexuals and academic freedom

Hoppe's statements and ideas concerning race and homosexuality have repeatedly provoked controversy among his libertarian peers and his colleagues at UNLV. Following a 4 March 2004, lecture on time preference at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), a student complained that Hoppe created a hostile classroom environment by stating that homosexuals tend to be more shortsighted than heterosexuals in their ability to save money and plan (economically) for the future, in part because they tend not to have children.[57] Hoppe also suggested that John Maynard Keynes's homosexuality might explain his economic views, with which Hoppe disagreed.[58] Hoppe also stated that very young and very old people, and couples without children, were less likely to plan for the future. Hoppe told a reporter that the comments lasted only 90 seconds of a 75-minute class, no students questioned the comments in that class, and that in 18 years of giving the same lecture all over the world, he had never previously received a complaint about it. At the request of university officials, Hoppe apologized to the class. He said, "Italians tend to eat more spaghetti than Germans, and Germans tend to eat more sauerkraut than Italians" and explained that he was speaking in generalities. Thereafter, Hoppe told the reporter, the student alleged that Hoppe did not take the complaint seriously and filed a formal complaint. Hoppe told the reporter that he felt as if it were he who was the victim in the incident and that the student should have been told to "grow up".[59]

An investigation was conducted and the university's provost, Raymond W. Alden III, issued Hoppe a non-disciplinary letter of instruction on 9 February 2005, with a finding that he had "created a hostile or intimidating educational environment in violation of the University's policies regarding discrimination as to sexual orientation". Alden also instructed Hoppe to "... cease mischaracterizing opinion as objective fact", asserted that Hoppe's opinion was not supported by peer-reviewed academic literature, and remarked that Hoppe had "refus[ed] to substantiate [his] in-class statements of fact ..."[60]

Hoppe appealed the decision, saying the university had "blatantly violated its contractual obligations" toward him and described the action as "frivolous interference with my right to academic freedom".[61] He was represented by the American Civil Liberties Union. The ACLU threatened legal action.[62] ACLU attorney Allen Lichtenstein said "The charge against professor Hoppe is totally specious and without merit".[59] The Nevada ACLU executive director said "We don't subscribe to Hans' theories and certainly understand why some students find them offensive ... But academic freedom means nothing if it doesn't protect the right of professors to present scholarly ideas that are relevant to their curricula, even if they are controversial and rub people the wrong way".[59] Alden's decision was picked up by Fox News and several blogs and libertarians organized a campaign to contact the university.[62] The university received two weeks of bad publicity and the Interim Chancellor (Nevada System of Higher Education) Jim Rogers expressed concerns about "any attempts to thwart free speech".[63]

Jim Rogers intervened in the matter. He rejected Hoppe's request for a one-year paid sabbatical,[64] and UNLV President Carol Harter acted upon Hoppe's appeal on 18 February 2005. She decided that Hoppe's views, even if non-mainstream or controversial, should not be cause for reprimanding him. She dismissed the discrimination complaint against Hoppe and the non-disciplinary letter was withdrawn from Hoppe's personnel file.[48] She wrote:

UNLV, in accordance with policy adopted by the Board of Regents, understands that the freedom afforded to Professor Hoppe and to all members of the academic community carries a significant corresponding academic responsibility. In the balance between freedoms and responsibilities, and where there may be ambiguity between the two, academic freedom must, in the end, be foremost.[65]

Hoppe later wrote about the incident and the UNLV investigation in an article entitled "My Battle With the Thought Police".[66] Martin Snyder of the American Association of University Professors wrote that he should not be "punished for freely expressing his opinions".[48]

Various controversies about academic freedom, including the Hoppe matter and remarks made by Harvard University President Lawrence Summers, prompted the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, to hold a conference on academic freedom in October 2005.[67] In 2009 UNLV proposed a new policy that included the encouragement of reporting by people who felt that they had encountered bias.[68] The proposed policy was criticized by the Nevada ACLU and some faculty members who remembered the Hoppe incident as adverse to academic freedom.[68][69]

Selected works

Books (authored)

German

- Handeln und Erkennen [Action and Cognition] (in German). Bern (1976). ISBN 978-3261019004. OCLC 2544452.

- Kritik der kausalwissenschaftlichen Sozialforschung [Critique of Causal Scientific Social Research] (in German). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag (1983). ISBN 978-3531116242. OCLC 10432202.

- Eigentum, Anarchie und Staat Property, Anarchy, and the State (in German). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag (1987). ISBN 978-3531118116. OCLC 18226538.

English

- A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism. Kluwer Academic Publishers (1988). ISBN 0898382793. Archived from the original.

- Audiobook, narrated by Jim Vann.

- Economic Science and the Austrian Method. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute (1995). ISBN 094546620X.

- Audiobook, narrated by Gennady Stolyarov II.

- Democracy: The God That Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy and Natural Order. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers (2001). ISBN 0765808684. OCLC 46384089.

- The Economics and Ethics of Private Property. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006. [2nd ed.] ISBN 0945466404.

Books (edited)

- The Myth of National Defense: Essays on the Theory and History of Security Production. Ludwig von Mises Institute (2003). ISBN 978-0945466376. OCLC 53401048.

Book contributions

- "Introduction." [1998]. In: The Ethics of Liberty, by Murray N. Rothbard. New York University Press (1998). ISBN 978-1610166645.

- "Government and the Private Production of Defense." In: The Myth of National Defense: Essays on the Theory and History of Security Production. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute (2003), pp. 335–368. ISBN 978-0945466376. OCLC 53401048.

- Audiobook, narrated by George Pickering.

Articles

- "On the Ultimate Justification of the Ethics of Private Property." Liberty, vol. 2, no. 1 (September 1988): 20–22.

- "Symposium: Breakthrough or Buncombe?" Liberty, vol. 2, no. 2 (November 1988): 44–54.

- Symposium proceedings featuring Murray N. Rothbard, D. Friedman, L. Yeager, D. Gordon and D. Rasmussen.

- "Socialism: A Property or Knowledge Problem?" Review of Austrian Economics, vol. 9 (March 1996): 143–149. doi:10.1007/BF01101888.

- "Small is Beautiful and Efficient: The Case for Secession." Telos, vol. 107 (Spring 1996).

- "The Libertarian Case for Free Trade and Restricted Immigration." Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 13, no. 2 (Summer 1998). Center for Libertarian Studies.

- Reprinted by the Center for Immigration Studies (May 2001).

- "On Property and Exploitation," with Walter Block. International Journal of Value-Based Management, vol. 15 (2002): 225–236.

- "My Battle with the Thought Police." Mises Daily (12 April 2005). Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Book reviews

- "In Defense of Extreme Rationalism: Thoughts on D. McCloskey's The Rhetoric of Economics." Review of The Rhetoric of Economics by Donald McCloskey. Review of Austrian Economics, vol. 3 (1989): 179–214.

Collected works

- Jacob, Thomas (editor). Hoppe Unplugged: Ansichten, Einsichten und Provokationen aus Interviews und Reden von Prof. Hans-Hermann Hoppe [in German]. Hamburg: tredition GmbH (2021). Online supplement.

- "Views, insights and provocations from interviews and speeches by Prof. Hans-Hermann Hoppe."

See also

- Anti-democratic thought

- Austrian School of Economics

- Criticism of democracy

- Curtis Yarvin

- Dark Enlightenment

- Dialectic

- Market anarchism

- Outline of democracy

- Propertarianism

- Right-libertarianism

- Ron Paul

- Soft despotism

- Sovereign democracy

- Totalitarian democracy

- Tyranny of the majority

- Voluntaryism

Further reading

- Hülsmann, Jörg Guido, and Stephan Kinsella (eds). Property, Freedom, and Society: Essays in Honor of Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Auburn, AL: Mises Institute, 2009.

- Deist, Jeff. "Hans-Hermann Hoppe: The In-Depth Interview." The Austrian, vol. 6, no. 2, March–April 2020, pp. 4–13.

References

- Deist, Jeff (March–April 2020). "Vol 6, No 2" (PDF). The Austrian. Auburn, AL: Mises Institute. p. 12. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- "The Gary G. Schlarbaum Prize". Mises Institute Awards. Ludwig von Mises Institute. 18 August 2014.

- Wile, Anthony (27 March 2011). "Dr. Hans-Hermann Hoppe on the Impracticality of One-World Government and the Failure of Western-style Democracy". The Daily Bell.

- History of PCPE, CEVRO Institute, Prague

- "Hans-Hermann Hoppe: Why Democracy Fails"

- Martland, Keir (2015). Liberty from a Beginner: Selected Essays. p. 61.

- Chakraverty, S. (2014). Mathematics of Uncertainty Modeling in the Analysis of Engineering and Science Problems. IGI Global. p. 38. ISBN 978-1466649910.

- Dieterle, David A. (2013). Economic Thinkers: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Greenwood. p. 145. ISBN 978-0313397462.

- "Hans-Hermann Hoppe". Ludwig von Mises Institute. 20 June 2014.

- "UNLV Catalog" (PDF). p. 47. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- newvalleymedia (7 October 2007). "Coming of Age with Murray". Mises Institute. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- Share, Cade (31 August 2012). "A Defense of Rothbardian Ethics via a Mediation of Hoppe and Rand". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. Penn State University Press. 12 (1): 117–150. doi:10.2307/41607996. JSTOR 41607996.

- David Gordon, Review of Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Democracy: The God that Failed, "The Mises Review" of Ludwig von Mises Institute, Volume 8, Number 1, Spring 2002; Volume 8, Number 1.

- Jeff Tucker interviews Hans-Hermann Hoppe Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine (1 October 2011)

- Lew Rockwell, introduction to Hoppe's A Short History of Man (2015), Auburn, Mississippi: Mises Institute, p. 9

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Juan Ramón Rallo interviews Mises Institute scholar Hans-Hermann Hoppe at the Instituto Juan de Mariana's". YouTube.

- Hans Herman Hoppe, The Economics and Ethics of Private Property, Second Edition, Mises Institute, p. xii, ISBN 978-0945466406.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (1995). L. Rockwell (Ed.), from Murray Rothbard, In Memoriam. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute. pp. 33–37

- Ketcham, Christopher (4 February 2021). "What the Far-Right Fascination With Pinochet's Death Squads Should Tell Us". The Intercept. The Intercept.

Hoppe’s claim to fame in the small world of libertarian economics was as second-stringer and all-around gopher to his hero and intimate friend, Ludwig von Mises

- Salihovic, Elnur (2015). Major Players in the Muslim Business World. Universal Publishers.

- Hoppe, Hans Hermann. "The Property And Freedom Society – Reflections After Five Years". lewrockwell.com. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Ganz, John (19 September 2017). "Perspective – Libertarians have more in common with the alt-right than they want you to think". Retrieved 16 October 2017 – via www.WashingtonPost.com.

- "The Story of the Mises Institute". Ludwig von Mises Institute. 19 September 2018.

- "Think Tanks and Liberty". Ludwig von Mises Institute. 27 April 2012.

- "Books & Library". 5 September 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Economics for Beginners Series". 4 June 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- "Graduate Program". Ludwig von Mises Institute. 23 July 2022.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (September 1988). "The Ultimate Justification of the Private Property Ethic" (PDF). Liberty. 2 (1): 20–22.

The mere fact that an individual argues presupposes that he owns himself and has a right to his own life and property. This provides a basis for libertarian theory radically different from both natural rights theory and utilitarianism.

- Symposium (November 1988). "Hans-Hermannn Hoppe's Argumentation Ethics: Breakthrough or Buncombe?" (PDF). Liberty. 2 (2): 44–54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017.

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe's Argumentation Ethic: A Critique, Robert Murphy and Gene Callahan. Relevant text on Page 3: "Therefore, [Hoppe] concludes that the libertarian view of property rights is the only one that can possibly be defended by rational argument."

- Kinsella, Stephan (13 March 2009). "Revisiting Argumentation Ethics". Mises Economics Blog. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

[A] number of thinkers weighed in, including Rothbard, ... Conway, ... D. Friedman, ... Machan, ... Lomasky, ... Yeager, ...Rasmussen, and others....

- Kinsella, Stephan (19 September 2002). "Defending Argumentation Ethics: Reply to Murphy & Callahan". Anti-State.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012. See also Kinsella's "Argumentation Ethics and Liberty: A Concise Guide".

- Murphy, Robert P.; Callahan, Gene (Spring 2006). "Hans-Hermann Hoppe's Argumentation Ethics: A Critique" (PDF). Journal of Libertarian Studies. 20 (2): 53–6. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "Comment on Hoppe / Comment on Osterfeld" (PDF). Austrian Economics Newsletter. 1988. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Long, Roderick T. "The Hoppriori Argument". Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Jason Brennan (12 December 2013). "Hoppe's Argumentation Ethics Argument Refuted in Under 60 Seconds". Bleeding Heart Libertarians. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- J. Mikael Olsson, Austrian Economics as Political Philosophy, Stockholm Studies in Politics 161, p. 157, 161.

- R.M. Pearce, Book Review: Democracy: the God That Failed, National Observer (Australia), No. 56, Autumn 2003.

- Fonseca, Joel (1 August 2013). "The Brazilian Philosophy Magazine Dicta & Contradicta Interviews Hans-Hermann Hoppe". Mises Institute Brazil

- Walter Block, Review of Democracy: The God that Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy, and Natural Order, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 61, No. 3, July 2002.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (1997). "On Theory and History. Reply to Benegas-Lynch Jr.". Published in Gerard Radnitzky, ed., Values and the Social Order, Vol. 3 (Aldershot: Avebury, 1997).

- "Alberto Benegas Lynch." Cato.org

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (1997). "On Theory and History. Reply to Benegas-Lynch Jr" (PDF). Values and the Social Order. 3: 1–8 – via HansHoppe.com.

- Hoppe, Democracy: The God That Failed, pp. 216–218

- kanopiadmin (11 April 2005). "My Battle With The Thought Police". Mises.org. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (2001). Democracy: The God That Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy and Natural Order, Transaction Publishers, p. 211. ISBN 1412815290

- Block, Walter (2007). "Plumb-Line Libertarianism: A Critique of Hoppe". Reason Papers.

- Snyder, Martin D. (1 March 2005). "Birds of a Feather?". Academe. American Association of University Professors. doi:10.2307/40253419. JSTOR 40253419. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (2011). Democracy: The God That Failed: The Economics and Politics of Monarchy, Democracy and Natural Order. Transaction Publishers. p. 206. ISBN 978-1412815291.

Did this not imply that vulgarity, obscenity, profanity, drug use, promiscuity, pornography, prostitution, homosexuality, polygamy, pediphilia or any other conceivable perversity or abnormality, insofar as they were victimless crimes, were no offenses at all but perfectly normal and legitimate activities and lifestyles?

- Walter Block (Loyola University New Orleans), "Libertarianism is unique; it belongs neither to the right nor the left: a critique of the views of Long, Holcombe, and Baden on the left, Hoppe, Feser and Paul on the right", undated, published at Ludwig von Mises Institute website, pp. 22–23.

- Guenzl, Simon (23 June 2016). "Public Property and the Libertarian Immigration Debate". Libertarian Papers. 8.

I conclude that supporting a legitimate role for the state as an immigration gatekeeper is inconsistent with Rothbardian and Hoppean libertarian anarchism, as well as with the associated strategy of advocating always and in every instance reductions in the state's role in society.

- Hans Hoppe, On Free Immigration and Forced Integration, LewRockwell.com, 1999.

- Anthony Gregory and Walter Block On Immigration: Reply to Hoppe, Journal of Libertarian Studies, Volume 21, No. 3, Fall 2007, pp. 25–42.

- Block, Walter (2008). Labor Economics From A Free Market Perspective: Employing The Unemployable. p. 225. ISBN 978-9814475860. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Walter Block and Gene Callahan, Is There a Right to Immigration?: A Libertarian Perspective, Human Rights Review, October–December 2003.

- Jacob Hornberger, Let's Stick with Traditional American Values!, The Future of Freedom Foundation, 1 February 2000.

- Snyder, Martin. "Birds of a Feather?". Academe. Vol. 91, no. 2. p. 127. ISSN 0190-2946.

So what ignited the controversy in Nevada? In March 2004, a student formally accused Hoppe of creating a hostile classroom environment during a lecture on time preference, a notion in economics identifying individuals' varying degrees of willingness to defer the immediate consumption of goods in favor of saving and investment. Hoppe opined that certain demographic groups, for instance homosexuals, tend to be more shortsighted in their economic outlook than those who have children.

- Snyder, Martin. "Birds of a Feather?". Academe. Vol. 91, no. 2. p. 127. ISSN 0190-2946.

He also suggested that the economic theories of John Maynard Keynes might be explained by Keynes's reputed homosexuality.

- Richard Lake, "UNLV accused of limiting free speech". Archived from the original on 9 February 2005. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Las Vegas Review-Journal, 5 February 2005. - Alden, III, Raymond W. (9 February 2005). "Findings and non-disciplinary letter of instruction" (PDF).

- Justin Chomintra, Professor, ACLU may sue UNLV Archived 3 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Rebel Yell, 10 February 2005; reprinted by Stephen Kinsella at Mises.org, 10 February 2005.

- "Efforts to punish UNLV professor gains exposure". Las Vegas Sun. 8 February 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Exoneration sought for UNLV professor". Las Vegas Sun. 21 February 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- "Rogers nixes Hoppe sabbatical". Las Vegas Sun. 23 February 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Carol Harter (18 February 2005). "Statement of Dr. Carol Harter, President of UNLV, regarding Professor Hans-Hermann Hoppe" (PDF).

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, "My Battle With the Thought Police", Ludwig von Mises Institute web site, 12 April 2005.

- The role of academic tenure was included during the conference. "Teachers' tenure on front burner". Las Vegas Sun. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- The proposed policy defined "bias incidents" as "'verbal, written, or physical acts of intimidation, coercion, interference, frivolous claims, discrimination, and sexual or other harassment motivated, in whole or in part, by bias" based on characteristics including actual or perceived race, religion, sex (including gender identity or gender expression or a pregnancy-related condition), physical appearance and political affiliation.' Hsu, Charlotte (25 April 2009). "ACLU airs free speech concerns on bias policy: Faculty express concern; UNLV official says proposal would encourage expression". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Policy on Bias Incidents and Hate Crimes (Final draft), University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Office of the Vice President for Student Affairs, Department of Police Services, Office of the Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion Policy on Bias Incidents and Hate Crimes.

External links

- Official website

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, The Mises Institute

- Property, Freedom, and Society – Festschrift (essays honoring Hoppe from the Mises Institute)

- The Property & Freedom Society

- Hoppe's archives at LewRockwell.com