Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 16 June [O.S. 5 June] 1723[1] – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish[lower-alpha 1] economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment.[7] Also seen as "The Father of Economics"[8] or "The Father of Capitalism",[9] he wrote two classic works, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). The latter, often abbreviated as The Wealth of Nations, is considered his magnum opus and the first modern work that treats economics as a comprehensive system and as an academic discipline. Smith refuses to explain the distribution of wealth and power in terms of God’s will and instead appeals to natural, political, social, economic and technological factors and the interactions between them. In his work, Smith introduced, among others, his theory of absolute advantage.[10]

Adam Smith FRSA | |

|---|---|

The posthumous c. 1800 Muir portrait at the Scottish National Gallery | |

| Born | c. 16 June [O.S. c. 5 June] 1723[1] |

| Died | 17 July 1790 (aged 67) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical liberalism |

Main interests | Political philosophy, ethics, economics |

Notable ideas | Classical economics Free market Economic liberalism Division of labour Absolute advantage Invisible hand |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

|

Smith studied social philosophy at the University of Glasgow and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was one of the first students to benefit from scholarships set up by fellow Scot John Snell. After graduating, he delivered a successful series of public lectures at the University of Edinburgh,[11] leading him to collaborate with David Hume during the Scottish Enlightenment. Smith obtained a professorship at Glasgow, teaching moral philosophy and during this time, wrote and published The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In his later life, he took a tutoring position that allowed him to travel throughout Europe, where he met other intellectual leaders of his day.

As a reaction to the common policy of protecting national markets and merchants, what came to be known as mercantilism, Smith laid the foundations of classical free market economic theory. The Wealth of Nations was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. In this and other works, he developed the concept of division of labour and expounded upon how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. Smith was controversial in his own day and his general approach and writing style were often satirised by writers such as Horace Walpole.[12]

Biography

Early life

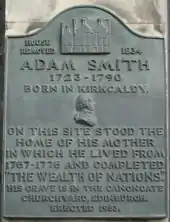

Smith was born in Kirkcaldy, in Fife, Scotland. His father, also Adam Smith, was a Scottish Writer to the Signet (senior solicitor), advocate and prosecutor (judge advocate) and also served as comptroller of the customs in Kirkcaldy.[13] Smith's mother was born Margaret Douglas, daughter of the landed Robert Douglas of Strathendry, also in Fife; she married Smith's father in 1720. Two months before Smith was born, his father died, leaving his mother a widow.[14] The date of Smith's baptism into the Church of Scotland at Kirkcaldy was 5 June 1723[15] and this has often been treated as if it were also his date of birth,[13] which is unknown.

Although few events in Smith's early childhood are known, the Scottish journalist John Rae, Smith's biographer, recorded that Smith was abducted by Romani at the age of three and released when others went to rescue him.[lower-alpha 2][17] Smith was close to his mother, who probably encouraged him to pursue his scholarly ambitions.[18] He attended the Burgh School of Kirkcaldy—characterised by Rae as "one of the best secondary schools of Scotland at that period"[16]—from 1729 to 1737, he learned Latin, mathematics, history, and writing.[18]

Formal education

Smith entered the University of Glasgow when he was 14 and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson.[18] Here he developed his passion for the philosophical concepts of reason, civilian liberties, and free speech. In 1740, he was the graduate scholar presented to undertake postgraduate studies at Balliol College, Oxford, under the Snell Exhibition.[19]

Smith considered the teaching at Glasgow to be far superior to that at Oxford, which he found intellectually stifling.[20] In Book V, Chapter II of The Wealth of Nations, he wrote: "In the University of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching." Smith is also reported to have complained to friends that Oxford officials once discovered him reading a copy of David Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature, and they subsequently confiscated his book and punished him severely for reading it.[16][21][22] According to William Robert Scott, "The Oxford of [Smith's] time gave little if any help towards what was to be his lifework."[23] Nevertheless, he took the opportunity while at Oxford to teach himself several subjects by reading many books from the shelves of the large Bodleian Library.[24] When Smith was not studying on his own, his time at Oxford was not a happy one, according to his letters.[25] Near the end of his time there, he began suffering from shaking fits, probably the symptoms of a nervous breakdown.[26] He left Oxford University in 1746, before his scholarship ended.[26][27]

In Book V of The Wealth of Nations, Smith comments on the low quality of instruction and the meager intellectual activity at English universities, when compared to their Scottish counterparts. He attributes this both to the rich endowments of the colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, which made the income of professors independent of their ability to attract students, and to the fact that distinguished men of letters could make an even more comfortable living as ministers of the Church of England.[22]

Smith's discontent at Oxford might be in part due to the absence of his beloved teacher in Glasgow, Francis Hutcheson, who was well regarded as one of the most prominent lecturers at the University of Glasgow in his day and earned the approbation of students, colleagues, and even ordinary residents with the fervor and earnestness of his orations (which he sometimes opened to the public). His lectures endeavoured not merely to teach philosophy, but also to make his students embody that philosophy in their lives, appropriately acquiring the epithet, the preacher of philosophy. Unlike Smith, Hutcheson was not a system builder; rather, his magnetic personality and method of lecturing so influenced his students and caused the greatest of those to reverentially refer to him as "the never to be forgotten Hutcheson"—a title that Smith in all his correspondence used to describe only two people, his good friend David Hume and influential mentor Francis Hutcheson.[28]

Teaching career

Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 at the University of Edinburgh,[29] sponsored by the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames.[30] His lecture topics included rhetoric and belles-lettres,[31] and later the subject of "the progress of opulence". On this latter topic, he first expounded his economic philosophy of "the obvious and simple system of natural liberty". While Smith was not adept at public speaking, his lectures met with success.[32]

In 1750, Smith met the philosopher David Hume, who was his senior by more than a decade. In their writings covering history, politics, philosophy, economics, and religion, Smith and Hume shared closer intellectual and personal bonds than with other important figures of the Scottish Enlightenment.[33]

In 1751, Smith earned a professorship at Glasgow University teaching logic courses, and in 1752, he was elected a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, having been introduced to the society by Lord Kames. When the head of Moral Philosophy in Glasgow died the next year, Smith took over the position.[32] He worked as an academic for the next 13 years, which he characterised as "by far the most useful and therefore by far the happiest and most honorable period [of his life]".[34]

Smith published The Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759, embodying some of his Glasgow lectures. This work was concerned with how human morality depends on sympathy between agent and spectator, or the individual and other members of society. Smith defined "mutual sympathy" as the basis of moral sentiments. He based his explanation, not on a special "moral sense" as the Third Lord Shaftesbury and Hutcheson had done, nor on utility as Hume did, but on mutual sympathy, a term best captured in modern parlance by the 20th-century concept of empathy, the capacity to recognise feelings that are being experienced by another being.

Following the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith became so popular that many wealthy students left their schools in other countries to enroll at Glasgow to learn under Smith.[35] At this time, Smith began to give more attention to jurisprudence and economics in his lectures and less to his theories of morals.[36] For example, Smith lectured that the cause of increase in national wealth is labour, rather than the nation's quantity of gold or silver, which is the basis for mercantilism, the economic theory that dominated Western European economic policies at the time.[37]

In 1762, the University of Glasgow conferred on Smith the title of Doctor of Laws (LL.D.).[38] At the end of 1763, he obtained an offer from British chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend—who had been introduced to Smith by David Hume—to tutor his stepson, Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch as preparation for a career in international politics. Smith resigned from his professorship in 1764 to take the tutoring position. He subsequently attempted to return the fees he had collected from his students because he had resigned partway through the term, but his students refused.[39]

Tutoring, travels, European intellectuals

Smith's tutoring job entailed touring Europe with Scott, during which time he educated Scott on a variety of subjects. He was paid £300 per year (plus expenses) along with a £300 per year pension; roughly twice his former income as a teacher.[39] Smith first travelled as a tutor to Toulouse, France, where he stayed for a year and a half. According to his own account, he found Toulouse to be somewhat boring, having written to Hume that he "had begun to write a book to pass away the time".[39] After touring the south of France, the group moved to Geneva, where Smith met with the philosopher Voltaire.[40]

From Geneva, the party moved to Paris. Here, Smith met American publisher and diplomat Benjamin Franklin, who a few years later would lead the opposition in the American colonies against four British resolutions from Charles Townshend (in history known as the Townshend Acts), which threatened American colonial self-government and imposed revenue duties on a number of items necessary to the colonies. Smith discovered the Physiocracy school founded by François Quesnay and discussed with their intellectuals.[41] Physiocrats were opposed to mercantilism, the dominating economic theory of the time, illustrated in their motto Laissez faire et laissez passer, le monde va de lui même! (Let do and let pass, the world goes on by itself!).

The wealth of France had been virtually depleted by Louis XIV[lower-alpha 3] and Louis XV in ruinous wars,[lower-alpha 4] and was further exhausted in aiding the American insurgents against the British. The excessive consumption of goods and services deemed to have no economic contribution was considered a source of unproductive labour, with France's agriculture the only economic sector maintaining the wealth of the nation. Given that the British economy of the day yielded an income distribution that stood in contrast to that which existed in France, Smith concluded that "with all its imperfections, [the Physiocratic school] is perhaps the nearest approximation to the truth that has yet been published upon the subject of political economy."[42] The distinction between productive versus unproductive labour—the physiocratic classe steril—was a predominant issue in the development and understanding of what would become classical economic theory.

Later years

In 1766, Henry Scott's younger brother died in Paris, and Smith's tour as a tutor ended shortly thereafter.[43] Smith returned home that year to Kirkcaldy, and he devoted much of the next decade to writing his magnum opus.[44] There, he befriended Henry Moyes, a young blind man who showed precocious aptitude. Smith secured the patronage of David Hume and Thomas Reid in the young man's education.[45] In May 1773, Smith was elected fellow of the Royal Society of London,[46] and was elected a member of the Literary Club in 1775. The Wealth of Nations was published in 1776 and was an instant success, selling out its first edition in only six months.[47]

In 1778, Smith was appointed to a post as commissioner of customs in Scotland and went to live with his mother (who died in 1784)[48] in Panmure House in Edinburgh's Canongate.[49] Five years later, as a member of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh when it received its royal charter, he automatically became one of the founding members of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[50] From 1787 to 1789, he occupied the honorary position of Lord Rector of the University of Glasgow.[51]

Death

Smith died in the northern wing of Panmure House in Edinburgh on 17 July 1790 after a painful illness. His body was buried in the Canongate Kirkyard.[52] On his deathbed, Smith expressed disappointment that he had not achieved more.[53]

Smith's literary executors were two friends from the Scottish academic world: the physicist and chemist Joseph Black and the pioneering geologist James Hutton.[54] Smith left behind many notes and some unpublished material, but gave instructions to destroy anything that was not fit for publication.[55] He mentioned an early unpublished History of Astronomy as probably suitable, and it duly appeared in 1795, along with other material such as Essays on Philosophical Subjects.[54]

Smith's library went by his will to David Douglas, Lord Reston (son of his cousin Colonel Robert Douglas of Strathendry, Fife), who lived with Smith.[56] It was eventually divided between his two surviving children, Cecilia Margaret (Mrs. Cunningham) and David Anne (Mrs. Bannerman). On the death in 1878 of her husband, the Reverend W. B. Cunningham of Prestonpans, Mrs. Cunningham sold some of the books. The remainder passed to her son, Professor Robert Oliver Cunningham of Queen's College, Belfast, who presented a part to the library of Queen's College. After his death, the remaining books were sold. On the death of Mrs. Bannerman in 1879, her portion of the library went intact to the New College (of the Free Church) in Edinburgh and the collection was transferred to the University of Edinburgh Main Library in 1972.

Personality and beliefs

Character

Not much is known about Smith's personal views beyond what can be deduced from his published articles. His personal papers were destroyed after his death at his request.[55] He never married,[58] and seems to have maintained a close relationship with his mother, with whom he lived after his return from France and who died six years before him.[59]

Smith was described by several of his contemporaries and biographers as comically absent-minded, with peculiar habits of speech and gait, and a smile of "inexpressible benignity".[60] He was known to talk to himself,[53] a habit that began during his childhood when he would smile in rapt conversation with invisible companions.[61] He also had occasional spells of imaginary illness,[53] and he is reported to have had books and papers placed in tall stacks in his study.[61] According to one story, Smith took Charles Townshend on a tour of a tanning factory, and while discussing free trade, Smith walked into a huge tanning pit from which he needed help to escape.[62] He is also said to have put bread and butter into a teapot, drunk the concoction, and declared it to be the worst cup of tea he ever had. According to another account, Smith distractedly went out walking in his nightgown and ended up 15 miles (24 km) outside of town, before nearby church bells brought him back to reality.[61][62]

James Boswell, who was a student of Smith's at Glasgow University, and later knew him at the Literary Club, says that Smith thought that speaking about his ideas in conversation might reduce the sale of his books, so his conversation was unimpressive. According to Boswell, he once told Sir Joshua Reynolds, that "he made it a rule when in company never to talk of what he understood".[63]

Smith has been alternatively described as someone who "had a large nose, bulging eyes, a protruding lower lip, a nervous twitch, and a speech impediment" and one whose "countenance was manly and agreeable".[22][64] Smith is said to have acknowledged his looks at one point, saying, "I am a beau in nothing but my books."[22] Smith rarely sat for portraits,[65] so almost all depictions of him created during his lifetime were drawn from memory. The best-known portraits of Smith are the profile by James Tassie and two etchings by John Kay.[66] The line engravings produced for the covers of 19th-century reprints of The Wealth of Nations were based largely on Tassie's medallion.[67]

Religious views

Considerable scholarly debate has occurred about the nature of Smith's religious views. Smith's father had shown a strong interest in Christianity and belonged to the moderate wing of the Church of Scotland.[68] The fact that Adam Smith received the Snell Exhibition suggests that he may have gone to Oxford with the intention of pursuing a career in the Church of England.[69]

Anglo-American economist Ronald Coase has challenged the view that Smith was a deist, based on the fact that Smith's writings never explicitly invoke God as an explanation of the harmonies of the natural or the human worlds.[70] According to Coase, though Smith does sometimes refer to the "Great Architect of the Universe", later scholars such as Jacob Viner have "very much exaggerated the extent to which Adam Smith was committed to a belief in a personal God",[71] a belief for which Coase finds little evidence in passages such as the one in the Wealth of Nations in which Smith writes that the curiosity of mankind about the "great phenomena of nature", such as "the generation, the life, growth, and dissolution of plants and animals", has led men to "enquire into their causes", and that "superstition first attempted to satisfy this curiosity, by referring all those wonderful appearances to the immediate agency of the gods. Philosophy afterwards endeavoured to account for them, from more familiar causes, or from such as mankind were better acquainted with than the agency of the gods".[71] Some authors argue that Smith's social and economic philosophy is inherently theological and that his entire model of social order is logically dependent on the notion of God's action in nature. Brendan Long argues that Smith was a theist,[73] whereas according to professor Gavin Kennedy, Smith was "in some sense" a Christian.[74]

Smith was also a close friend of David Hume, who, despite debate about his religious views in modern scholarship, was commonly characterised in his own time as an atheist.[75] The publication in 1777 of Smith's letter to William Strahan, in which he described Hume's courage in the face of death in spite of his irreligiosity, attracted considerable controversy.[76]

Published works

The Theory of Moral Sentiments

In 1759, Smith published his first work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, sold by co-publishers Andrew Millar of London and Alexander Kincaid of Edinburgh.[77] Smith continued making extensive revisions to the book until his death.[lower-alpha 5] Although The Wealth of Nations is widely regarded as Smith's most influential work, Smith himself is believed to have considered The Theory of Moral Sentiments to be a superior work.[79]

In the work, Smith critically examines the moral thinking of his time, and suggests that conscience arises from dynamic and interactive social relationships through which people seek "mutual sympathy of sentiments."[80] His goal in writing the work was to explain the source of mankind's ability to form moral judgment, given that people begin life with no moral sentiments at all. Smith proposes a theory of sympathy, in which the act of observing others and seeing the judgments they form of both others and oneself makes people aware of themselves and how others perceive their behaviour. The feedback we receive from perceiving (or imagining) others' judgment creates an incentive to achieve "mutual sympathy of sentiments" with them and leads people to develop habits, and then principles, of behaviour, which come to constitute one's conscience.[81]

Some scholars have perceived a conflict between The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations; the former emphasises sympathy for others, while the latter focuses on the role of self-interest.[82] In recent years, however, some scholars[83][84][85] of Smith's work have argued that no contradiction exists. They claim that in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith develops a theory of psychology in which individuals seek the approval of the "impartial spectator" as a result of a natural desire to have outside observers sympathise with their sentiments. Rather than viewing The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations as presenting incompatible views of human nature, some Smith scholars regard the works as emphasising different aspects of human nature that vary depending on the situation. In the first part – The Theory of Moral Sentiments – he laid down the foundation of his vision of humanity and society. In the second – The Wealth of Nations – he elaborated on the virtue of prudence, which for him meant the relations between people in the private sphere of the economy. It was his plan to further elaborate on the virtue of justice in the third book.[86] Otteson argues that both books are Newtonian in their methodology and deploy a similar "market model" for explaining the creation and development of large-scale human social orders, including morality, economics, as well as language.[87] Ekelund and Hebert offer a differing view, observing that self-interest is present in both works and that "in the former, sympathy is the moral faculty that holds self-interest in check, whereas in the latter, competition is the economic faculty that restrains self-interest."[88]

The Wealth of Nations

Disagreement exists between classical and neoclassical economists about the central message of Smith's most influential work: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Neoclassical economists emphasise Smith's invisible hand,[89] a concept mentioned in the middle of his work – Book IV, Chapter II – and classical economists believe that Smith stated his programme for promoting the "wealth of nations" in the first sentences, which attributes the growth of wealth and prosperity to the division of labour. He elaborated on the virtue of prudence, which for him meant the relations between people in the private sphere of the economy. It was his plan to further elaborate on the virtue of justice in the third book.[86]

Smith used the term "the invisible hand" in "History of Astronomy"[90] referring to "the invisible hand of Jupiter", and once in each of his The Theory of Moral Sentiments[91] (1759) and The Wealth of Nations[92] (1776). This last statement about "an invisible hand" has been interpreted in numerous ways.

As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.

Those who regard that statement as Smith's central message also quote frequently Smith's dictum:[93]

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

However, in The Theory of Moral Sentiments he had a more sceptical approach to self-interest as driver of behaviour:

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.

Smith's statement about the benefits of "an invisible hand" may be meant to answer Mandeville's contention that "Private Vices ... may be turned into Public Benefits".[94] It shows Smith's belief that when an individual pursues his self-interest under conditions of justice, he unintentionally promotes the good of society. Self-interested competition in the free market, he argued, would tend to benefit society as a whole by keeping prices low, while still building in an incentive for a wide variety of goods and services. Nevertheless, he was wary of businessmen and warned of their "conspiracy against the public or in some other contrivance to raise prices".[95] Again and again, Smith warned of the collusive nature of business interests, which may form cabals or monopolies, fixing the highest price "which can be squeezed out of the buyers".[96] Smith also warned that a business-dominated political system would allow a conspiracy of businesses and industry against consumers, with the former scheming to influence politics and legislation. Smith states that the interest of manufacturers and merchants "in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public ... The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order, ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention."[97] Thus Smith's chief worry seems to be when business is given special protections or privileges from government; by contrast, in the absence of such special political favours, he believed that business activities were generally beneficial to the whole society:

It is the great multiplication of the production of all the different arts, in consequence of the division of labour, which occasions, in a well-governed society, that universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people. Every workman has a great quantity of his own work to dispose of beyond what he himself has occasion for; and every other workman being exactly in the same situation, he is enabled to exchange a great quantity of his own goods for a great quantity, or, what comes to the same thing, for the price of a great quantity of theirs. He supplies them abundantly with what they have occasion for, and they accommodate him as amply with what he has occasion for, and a general plenty diffuses itself through all the different ranks of society. (The Wealth of Nations, I.i.10)

The neoclassical interest in Smith's statement about "an invisible hand" originates in the possibility of seeing it as a precursor of neoclassical economics and its concept of general equilibrium; Samuelson's "Economics" refers six times to Smith's "invisible hand". To emphasise this connection, Samuelson[98] quotes Smith's "invisible hand" statement substituting "general interest" for "public interest". Samuelson[99] concludes: "Smith was unable to prove the essence of his invisible-hand doctrine. Indeed, until the 1940s, no one knew how to prove, even to state properly, the kernel of truth in this proposition about perfectly competitive market."

Very differently, classical economists see in Smith's first sentences his programme to promote "The Wealth of Nations". Using the physiocratical concept of the economy as a circular process, to secure growth the inputs of Period 2 must exceed the inputs of Period 1. Therefore, those outputs of Period 1 which are not used or usable as inputs of Period 2 are regarded as unproductive labour, as they do not contribute to growth. This is what Smith had heard in France from, among others, François Quesnay, whose ideas Smith was so impressed by that he might have dedicated The Wealth of Nations to him had he not died beforehand.[100][101] To this French insight that unproductive labour should be reduced to use labour more productively, Smith added his own proposal, that productive labour should be made even more productive by deepening the division of labour.[102] Smith argued that deepening the division of labour under competition leads to greater productivity, which leads to lower prices and thus an increasing standard of living—"general plenty" and "universal opulence"—for all. Extended markets and increased production lead to the continuous reorganisation of production and the invention of new ways of producing, which in turn lead to further increased production, lower prices, and improved standards of living. Smith's central message is, therefore, that under dynamic competition, a growth machine secures "The Wealth of Nations". Smith's argument predicted Britain's evolution as the workshop of the world, underselling and outproducing all its competitors. The opening sentences of the "Wealth of Nations" summarise this policy:

The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes ... . [T]his produce ... bears a greater or smaller proportion to the number of those who are to consume it ... .[B]ut this proportion must in every nation be regulated by two different circumstances;

- first, by the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which its labour is generally applied; and,

- secondly, by the proportion between the number of those who are employed in useful labour, and that of those who are not so employed [emphasis added].[103]

However, Smith added that the "abundance or scantiness of this supply too seems to depend more upon the former of those two circumstances than upon the latter."[104]

Other works

Shortly before his death, Smith had nearly all his manuscripts destroyed. In his last years, he seemed to have been planning two major treatises, one on the theory and history of law and one on the sciences and arts. The posthumously published Essays on Philosophical Subjects, a history of astronomy down to Smith's own era, plus some thoughts on ancient physics and metaphysics, probably contain parts of what would have been the latter treatise. Lectures on Jurisprudence were notes taken from Smith's early lectures, plus an early draft of The Wealth of Nations, published as part of the 1976 Glasgow Edition of the works and correspondence of Smith. Other works, including some published posthumously, include Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue, and Arms (1763) (first published in 1896); and Essays on Philosophical Subjects (1795).[105]

Legacy

In economics and moral philosophy

The Wealth of Nations was a precursor to the modern academic discipline of economics. In this and other works, Smith expounded how rational self-interest and competition can lead to economic prosperity. Smith was controversial in his own day and his general approach and writing style were often satirised by Tory writers in the moralising tradition of Hogarth and Swift, as a discussion at the University of Winchester suggests.[106] In 2005, The Wealth of Nations was named among the 100 Best Scottish Books of all time.[107]

In light of the arguments put forward by Smith and other economic theorists in Britain, academic belief in mercantilism began to decline in Britain in the late 18th century. During the Industrial Revolution, Britain embraced free trade and Smith's laissez-faire economics, and via the British Empire, used its power to spread a broadly liberal economic model around the world, characterised by open markets, and relatively barrier-free domestic and international trade.[108]

George Stigler attributes to Smith "the most important substantive proposition in all of economics". It is that, under competition, owners of resources (for example labour, land, and capital) will use them most profitably, resulting in an equal rate of return in equilibrium for all uses, adjusted for apparent differences arising from such factors as training, trust, hardship, and unemployment.[109]

Paul Samuelson finds in Smith's pluralist use of supply and demand as applied to wages, rents, and profit a valid and valuable anticipation of the general equilibrium modelling of Walras a century later. Smith's allowance for wage increases in the short and intermediate term from capital accumulation and invention contrasted with Malthus, Ricardo, and Karl Marx in their propounding a rigid subsistence–wage theory of labour supply.[110]

Joseph Schumpeter criticised Smith for a lack of technical rigour, yet he argued that this enabled Smith's writings to appeal to wider audiences: "His very limitation made for success. Had he been more brilliant, he would not have been taken so seriously. Had he dug more deeply, had he unearthed more recondite truth, had he used more difficult and ingenious methods, he would not have been understood. But he had no such ambitions; in fact he disliked whatever went beyond plain common sense. He never moved above the heads of even the dullest readers. He led them on gently, encouraging them by trivialities and homely observations, making them feel comfortable all along."[111]

Classical economists presented competing theories to those of Smith, termed the "labour theory of value". Later Marxian economics descending from classical economics also use Smith's labour theories, in part. The first volume of Karl Marx's major work, Das Kapital, was published in German in 1867. In it, Marx focused on the labour theory of value and what he considered to be the exploitation of labour by capital.[112][113] The labour theory of value held that the value of a thing was determined by the labour that went into its production. This contrasts with the modern contention of neoclassical economics, that the value of a thing is determined by what one is willing to give up to obtain the thing.

The body of theory later termed "neoclassical economics" or "marginalism" formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term "economics" was popularised by such neoclassical economists as Alfred Marshall as a concise synonym for "economic science" and a substitute for the earlier, broader term "political economy" used by Smith.[114][115] This corresponded to the influence on the subject of mathematical methods used in the natural sciences.[116] Neoclassical economics systematised supply and demand as joint determinants of price and quantity in market equilibrium, affecting both the allocation of output and the distribution of income. It dispensed with the labour theory of value of which Smith was most famously identified with in classical economics, in favour of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and a more general theory of costs on the supply side.[117]

The bicentennial anniversary of the publication of The Wealth of Nations was celebrated in 1976, resulting in increased interest for The Theory of Moral Sentiments and his other works throughout academia. After 1976, Smith was more likely to be represented as the author of both The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, and thereby as the founder of a moral philosophy and the science of economics. His homo economicus or "economic man" was also more often represented as a moral person. Additionally, economists David Levy and Sandra Peart in "The Secret History of the Dismal Science" point to his opposition to hierarchy and beliefs in inequality, including racial inequality, and provide additional support for those who point to Smith's opposition to slavery, colonialism, and empire. Emphasised also are Smith's statements of the need for high wages for the poor, and the efforts to keep wages low. In The "Vanity of the Philosopher: From Equality to Hierarchy in Postclassical Economics", Peart and Levy also cite Smith's view that a common street porter was not intellectually inferior to a philosopher,[118] and point to the need for greater appreciation of the public views in discussions of science and other subjects now considered to be technical. They also cite Smith's opposition to the often expressed view that science is superior to common sense.[119]

Smith also explained the relationship between growth of private property and civil government:

Men may live together in society with some tolerable degree of security, though there is no civil magistrate to protect them from the injustice of those passions. But avarice and ambition in the rich, in the poor the hatred of labour and the love of present ease and enjoyment, are the passions which prompt to invade property, passions much more steady in their operation, and much more universal in their influence. Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many. The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions. It is only under the shelter of the civil magistrate that the owner of that valuable property, which is acquired by the labour of many years, or perhaps of many successive generations, can sleep a single night in security. He is at all times surrounded by unknown enemies, whom, though he never provoked, he can never appease, and from whose injustice he can be protected only by the powerful arm of the civil magistrate continually held up to chastise it. The acquisition of valuable and extensive property, therefore, necessarily requires the establishment of civil government. Where there is no property, or at least none that exceeds the value of two or three days' labour, civil government is not so necessary. Civil government supposes a certain subordination. But as the necessity of civil government gradually grows up with the acquisition of valuable property, so the principal causes which naturally introduce subordination gradually grow up with the growth of that valuable property. (...) Men of inferior wealth combine to defend those of superior wealth in the possession of their property, in order that men of superior wealth may combine to defend them in the possession of theirs. All the inferior shepherds and herdsmen feel that the security of their own herds and flocks depends upon the security of those of the great shepherd or herdsman; that the maintenance of their lesser authority depends upon that of his greater authority, and that upon their subordination to him depends his power of keeping their inferiors in subordination to them. They constitute a sort of little nobility, who feel themselves interested to defend the property and to support the authority of their own little sovereign in order that he may be able to defend their property and to support their authority. Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.[120]

In British imperial debates

Smith opposed empire. He challenged ideas that colonies were key to British prosperity and power. He rejected that other cultures, such as China and India, were culturally and developmentally inferior to Europe. While he favored "commercial society", he did not support radical social change and the imposition of commercial society on other societies. He proposed that colonies be given independence or that full political rights be extended to colonial subjects.[121]

Smith's chapter on colonies, in turn, would help shape British imperial debates from the mid-19th century onward. The Wealth of Nations would become an ambiguous text regarding the imperial question. In his chapter on colonies, Smith pondered how to solve the crisis developing across the Atlantic among the empire's 13 American colonies. He offered two different proposals for easing tensions. The first proposal called for giving the colonies their independence, and by thus parting on a friendly basis, Britain would be able to develop and maintain a free-trade relationship with them, and possibly even an informal military alliance. Smith's second proposal called for a theoretical imperial federation that would bring the colonies and the metropole closer together through an imperial parliamentary system and imperial free trade.[122]

Smith's most prominent disciple in 19th-century Britain, peace advocate Richard Cobden, preferred the first proposal. Cobden would lead the Anti-Corn Law League in overturning the Corn Laws in 1846, shifting Britain to a policy of free trade and empire "on the cheap" for decades to come. This hands-off approach toward the British Empire would become known as Cobdenism or the Manchester School.[123] By the turn of the century, however, advocates of Smith's second proposal such as Joseph Shield Nicholson would become ever more vocal in opposing Cobdenism, calling instead for imperial federation.[124] As Marc-William Palen notes: "On the one hand, Adam Smith's late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Cobdenite adherents used his theories to argue for gradual imperial devolution and empire 'on the cheap'. On the other, various proponents of imperial federation throughout the British World sought to use Smith's theories to overturn the predominant Cobdenite hands-off imperial approach and instead, with a firm grip, bring the empire closer than ever before."[125] Smith's ideas thus played an important part in subsequent debates over the British Empire.

Portraits, monuments, and banknotes

Smith has been commemorated in the UK on banknotes printed by two different banks; his portrait has appeared since 1981 on the £50 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in Scotland,[126][127] and in March 2007 Smith's image also appeared on the new series of £20 notes issued by the Bank of England, making him the first Scotsman to feature on an English banknote.[128]

A large-scale memorial of Smith by Alexander Stoddart was unveiled on 4 July 2008 in Edinburgh. It is a 10-foot (3.0 m)-tall bronze sculpture and it stands above the Royal Mile outside St Giles' Cathedral in Parliament Square, near the Mercat cross.[129] 20th-century sculptor Jim Sanborn (best known for the Kryptos sculpture at the United States Central Intelligence Agency) has created multiple pieces which feature Smith's work. At Central Connecticut State University is Circulating Capital, a tall cylinder which features an extract from The Wealth of Nations on the lower half, and on the upper half, some of the same text, but represented in binary code.[130] At the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, outside the Belk College of Business Administration, is Adam Smith's Spinning Top.[131][132] Another Smith sculpture is at Cleveland State University.[133] He also appears as the narrator in the 2013 play The Low Road, centred on a proponent on laissez-faire economics in the late 18th century, but dealing obliquely with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the recession which followed; in the premiere production, he was portrayed by Bill Paterson.

A bust of Smith is in the Hall of Heroes of the National Wallace Monument in Stirling.

Residence

Adam Smith resided at Panmure House from 1778 to 1790. This residence has now been purchased by the Edinburgh Business School at Heriot-Watt University and fundraising has begun to restore it.[134][135] Part of the Northern end of the original building appears to have been demolished in the 19th century to make way for an iron foundry.

As a symbol of free-market economics

Smith has been celebrated by advocates of free-market policies as the founder of free-market economics, a view reflected in the naming of bodies such as the Adam Smith Institute in London, multiple entities known as the "Adam Smith Society", including an historical Italian organization,[136] and the U.S.-based Adam Smith Society,[137][138] and the Australian Adam Smith Club,[139] and in terms such as the Adam Smith necktie.[140]

Former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan argues that, while Smith did not coin the term laissez-faire, "it was left to Adam Smith to identify the more-general set of principles that brought conceptual clarity to the seeming chaos of market transactions". Greenspan continues that The Wealth of Nations was "one of the great achievements in human intellectual history".[141] P.J. O'Rourke describes Smith as the "founder of free market economics".[142]

Other writers have argued that Smith's support for laissez-faire (which in French means leave alone) has been overstated. Herbert Stein wrote that the people who "wear an Adam Smith necktie" do it to "make a statement of their devotion to the idea of free markets and limited government", and that this misrepresents Smith's ideas. Stein writes that Smith "was not pure or doctrinaire about this idea. He viewed government intervention in the market with great skepticism...yet he was prepared to accept or propose qualifications to that policy in the specific cases where he judged that their net effect would be beneficial and would not undermine the basically free character of the system. He did not wear the Adam Smith necktie." In Stein's reading, The Wealth of Nations could justify the Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, mandatory employer health benefits, environmentalism, and "discriminatory taxation to deter improper or luxurious behavior".[143]

Similarly, Vivienne Brown stated in The Economic Journal that in the 20th-century United States, Reaganomics supporters, The Wall Street Journal, and other similar sources have spread among the general public a partial and misleading vision of Smith, portraying him as an "extreme dogmatic defender of laissez-faire capitalism and supply-side economics".[144] In fact, The Wealth of Nations includes the following statement on the payment of taxes:

The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state.[145]

Some commentators have argued that Smith's works show support for a progressive, not flat, income tax and that he specifically named taxes that he thought should be required by the state, among them luxury-goods taxes and tax on rent.[146] Yet Smith argued for the "impossibility of taxing the people, in proportion to their economic revenue, by any capitation".[147] Smith argued that taxes should principally go toward protecting "justice" and "certain publick institutions" that were necessary for the benefit of all of society, but that could not be provided by private enterprise.[148]

Additionally, Smith outlined the proper expenses of the government in The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Ch. I. Included in his requirements of a government is to enforce contracts and provide justice system, grant patents and copy rights, provide public goods such as infrastructure, provide national defence, and regulate banking. The role of the government was to provide goods "of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual" such as roads, bridges, canals, and harbours. He also encouraged invention and new ideas through his patent enforcement and support of infant industry monopolies. He supported partial public subsidies for elementary education, and he believed that competition among religious institutions would provide general benefit to the society. In such cases, however, Smith argued for local rather than centralised control: "Even those publick works which are of such a nature that they cannot afford any revenue for maintaining themselves ... are always better maintained by a local or provincial revenue, under the management of a local and provincial administration, than by the general revenue of the state" (Wealth of Nations, V.i.d.18). Finally, he outlined how the government should support the dignity of the monarch or chief magistrate, such that they are equal or above the public in fashion. He even states that monarchs should be provided for in a greater fashion than magistrates of a republic because "we naturally expect more splendor in the court of a king than in the mansion-house of a doge".[149] In addition, he allowed that in some specific circumstances, retaliatory tariffs may be beneficial:

The recovery of a great foreign market will generally more than compensate the transitory inconvenience of paying dearer during a short time for some sorts of goods.[150]

However, he added that in general, a retaliatory tariff "seems a bad method of compensating the injury done to certain classes of our people, to do another injury ourselves, not only to those classes, but to almost all the other classes of them".[151]

Economic historians such as Jacob Viner regard Smith as a strong advocate of free markets and limited government (what Smith called "natural liberty"), but not as a dogmatic supporter of laissez-faire.[152]

Economist Daniel Klein believes using the term "free-market economics" or "free-market economist" to identify the ideas of Smith is too general and slightly misleading. Klein offers six characteristics central to the identity of Smith's economic thought and argues that a new name is needed to give a more accurate depiction of the "Smithian" identity.[153][154] Economist David Ricardo set straight some of the misunderstandings about Smith's thoughts on free market. Most people still fall victim to the thinking that Smith was a free-market economist without exception, though he was not. Ricardo pointed out that Smith was in support of helping infant industries. Smith believed that the government should subsidise newly formed industry, but he did fear that when the infant industry grew into adulthood, it would be unwilling to surrender the government help.[155] Smith also supported tariffs on imported goods to counteract an internal tax on the same good. Smith also fell to pressure in supporting some tariffs in support for national defence.[155]

Some have also claimed, Emma Rothschild among them, that Smith would have supported a minimum wage,[156] although no direct textual evidence supports the claim. Indeed, Smith wrote:

The price of labour, it must be observed, cannot be ascertained very accurately anywhere, different prices being often paid at the same place and for the same sort of labour, not only according to the different abilities of the workmen, but according to the easiness or hardness of the masters. Where wages are not regulated by law, all that we can pretend to determine is what are the most usual; and experience seems to show that law can never regulate them properly, though it has often pretended to do so. (The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, Chapter 8)

However, Smith also noted, to the contrary, the existence of an imbalanced, inequality of bargaining power:[157]

A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long run, the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him, but the necessity is not so immediate.

See also

- Critique of political economy

- Organizational capital

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of Fellows of the Royal Society of Arts

- People on Scottish banknotes

References

Informational notes

- Smith was described as a North Briton and Scot.[6]

- In Life of Adam Smith, Rae writes: "In his fourth year, while on a visit to his grandfather's house at Strathendry on the banks of the Leven, [Smith] was stolen by a passing band of gypsies, and for a time could not be found. But presently a gentleman arrived who had met a Romani woman a few miles down the road carrying a child that was crying piteously. Scouts were immediately dispatched in the direction indicated, and they came upon the woman in Leslie wood. As soon as she saw them she threw her burden down and escaped, and the child was brought back to his mother. [Smith] would have made, I fear, a poor gypsy."[16]

- During the reign of Louis XIV, the population shrunk by 4 million and agricultural productivity was reduced by one-third while the taxes had increased. Cusminsky, Rosa, de Cendrero, 1967, Los Fisiócratas, Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina, p. 6

- 1701–1714 War of the Spanish Succession, 1688–1697 War of the Grand Alliance, 1672–1678 Franco-Dutch War, 1667–1668 War of Devolution, 1618–1648 Thirty Years' War

- The 6 editions of The Theory of Moral Sentiments were published in 1759, 1761, 1767, 1774, 1781, and 1790, respectively.[78]

Citations

- "Adam Smith (1723–1790)". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

Adam Smith's exact date of birth is unknown, but he was baptised on 5 June 1723.

- Nevin, Seamus (2013). "Richard Cantillon: The Father of Economics". History Ireland. 21 (2): 20–23. JSTOR 41827152.

- Porta, Pier L. "Lombard Enlightenment and Classical Political Economy." European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 18.4 (2011): 521–550. Print. (Page-542-543)

- Billington, James H. (1999). Fire in the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith. Transaction Publishers. p. 302.

- Stedman Jones, Gareth (2006). "Saint-Simon and the Liberal origins of the Socialist critique of Political Economy". In Aprile, Sylvie; Bensimon, Fabrice (eds.). La France et l'Angleterre au XIXe siècle. Échanges, représentations, comparaisons. Créaphis. pp. 21–47.

- Williams, Gwydion M. (2000). Adam Smith, Wealth Without Nations. London: Athol Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-85034-084-6. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- "BBC – History – Scottish History". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 April 2001. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- —Brown, Vivienne (5 December 2008). "Mere Inventions of the Imagination': A Survey of Recent Literature on Adam Smith". Cambridge University Press. 13 (2): 281–312. doi:10.1017/S0266267100004521. S2CID 145093382. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

—Berry, Christopher J. (2018). Adam Smith Very Short Introductions Series. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-198-78445-6. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

—Sharma, Rakesh. "Adam Smith: The Father of Economics". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2019. - —"Adam Smith: Father of Capitalism". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

—Bassiry, G. R.; Jones, Marc (1993). "Adam Smith and the ethics of contemporary capitalism". Journal of Business Ethics. 12 (1026): 621–627. doi:10.1007/BF01845899. S2CID 51746709.

—Newbert, Scott L. (30 November 2017). "Lessons on social enterprise from the father of capitalism: A dialectical analysis of Adam Smith". Academy of Management Journal. 2016 (1): 12046. doi:10.5465/ambpp.2016.12046abstract. ISSN 2151-6561.

—Rasmussen, Dennis C. (2017). The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship That Shaped Modern Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-400-88846-7. - "Absolute Advantage – Ability to Produce More than Anyone Else". Corporate Finance Institute. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- "Adam Smith: Biography on Undiscovered Scotland". www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- John, McMurray (19 March 2017). "Capitalism's 'Founding Father' Often Quoted, Frequently Misconstrued". Investor's Business Daily. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Rae 1895, p. 1

- Bussing-Burks 2003, pp. 38–39

- Buchan 2006, p. 12

- Rae 1895, p. 5

- "Fife Place-name Data :: Strathenry". fife-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 39

- Buchan 2006, p. 22

- Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 41

- Rae 1895, p. 24

- Buchholz 1999, p. 12

- Introductory Economics. New Age Publishers. 2006. p. 4. ISBN 81-224-1830-9.

- Rae 1895, p. 22

- Rae 1895, pp. 24–25

- Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 42

- Buchan 2006, p. 29

- Scott, W. R. "The Never to Be Forgotten Hutcheson: Excerpts from W. R. Scott," Econ Journal Watch 8(1): 96–109, January 2011. Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Adam Smith". Biography. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Rae 1895, p. 30

- Smith, A. ([1762] 1985). Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres [1762]. vol. IV of the Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1984). Retrieved 16 February 2012

- Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 43

- Winch, Donald (September 2004). "Smith, Adam (bap. 1723, d. 1790)". Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Rae 1895, p. 42

- Buchholz 1999, p. 15

- Buchan 2006, p. 67

- Buchholz 1999, p. 13

- "MyGlasgow – Archive Services – Exhibitions – Adam Smith in Glasgow – Photo Gallery – Honorary degree". University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Buchholz 1999, p. 16

- Buchholz 1999, pp. 16–17

- Buchholz 1999, p. 17

- Smith, A., 1976, The Wealth of Nations edited by R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2b, p. 678.

- Buchholz 1999, p. 18

- Buchan 2006, p. 90

- Dr James Currie to Thomas Creevey, 24 February 1793, Lpool RO, Currie MS 920 CUR

- Buchan 2006, p. 89

- Buchholz 1999, p. 19

- Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1967). The Story of Civilization: Rousseau and Revolution. MJF Books. ISBN 1567310214.

- Buchan 2006, p. 128

- Buchan 2006, p. 133

- Buchan 2006, p. 137

- Buchan 2006, p. 145

- Bussing-Burks 2003, p. 53

- Buchan 2006, p. 25

- Buchan 2006, p. 88

- Bonar 1894, p. xiv.

- Bonar 1894, pp. xx–xxiv

- Buchan 2006, p. 11

- Buchan 2006, p. 134

- Rae 1895, p. 262

- Skousen 2001, p. 32

- Buchholz 1999, p. 14

- Boswell's Life of Samuel Johnson, 1780.

- Ross 2010, p. 330

- Stewart, Dugald (1853). The Works of Adam Smith: With An Account of His Life and Writings. London: Henry G. Bohn. lxix. OCLC 3226570. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Rae 1895, pp. 376–377

- Bonar 1894, p. xxi

- Ross 1995, p. 15

- "Times obituary of Adam Smith". The Times. 24 July 1790. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Coase 1976, pp. 529–546

- Coase 1976, p. 538

- Long, Brendan (2006), Brown, Vivienne (ed.), "Adam Smith's natural theology of society", The Adam Smith Review, Routledge, vol. 2, doi:10.4324/9780203966365, ISBN 978-0-203-96636-5, retrieved 31 May 2022

- Kennedy, Gavin (2011). "The Hidden Adam Smith In His Alleged Theology". Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 33 (3): 385–402. doi:10.1017/S1053837211000204. ISSN 1469-9656. S2CID 154779976.

- "Hume on Religion". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- Eric Schliesser (2003). "The Obituary of a Vain Philosopher: Adam Smith's Reflections on Hume's Life" (PDF). Hume Studies. 29 (2): 327–362. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Andrew Millar Project, University of Edinburgh". millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Adam Smith, Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence Vol. 1 The Theory of Moral Sentiments [1759].

- Rae 1895

- Falkner, Robert (1997). "Biography of Smith". Liberal Democrat History Group. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- Smith 2002, p. xv

- Viner 1991, p. 250

- Wight, Jonathan B. Saving Adam Smith. Upper Saddle River: Prentic-Hall, Inc., 2002.

- Robbins, Lionel. A History of Economic Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Brue, Stanley L., and Randy R. Grant. The Evolution of Economic Thought. Mason: Thomson Higher Education, 2007.

- Van Schie, Patrick. "The Theory of Moral Sentiments". European Liberal Forum. European Liberal Forum. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- Otteson, James R. 2002, Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Ekelund, R. & Hebert, R. 2007, A History of Economic Theory and Method 5th Edition. Waveland Press, United States, p. 105.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Wealth of Nations edited by R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2a, p. 456.

- Smith, A., 1980, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 3, p. 49, edited by W. P. D. Wightman and J. C. Bryce, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 1, pp. 184–185, edited by D. D. Raphael and A. L. Macfie, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, vol. 2a, p. 456, edited by R. H. Cambell and A. S. Skinner, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, pp. 26–27.

- Mandeville, B., 1724, The Fable of the Bees, London: Tonson.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, pp. 145, 158.

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, p. 79.

- Gopnik, Adam (10 October 2010). "Market Man". The New Yorker. No. 18 October 2010. p. 82. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Samuelson, P. A./Nordhaus, William D., 1989, Economics, 13th edition, N.Y. et al.: McGraw-Hill, p. 825.

- Samuelson, P. A./Nordhaus, William D., 1989, idem, p. 825.

- Buchan 2006, p. 80

- Stewart, D., 1799, Essays on Philosophical Subjects, to which is prefixed An Account of the Life and Writings of the Author by Dugald Stewart, F.R.S.E., Basil; from the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Read by Mr. Stewart, 21 January, and 18 March 1793; in: The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, 1982, vol. 3, pp. 304 ff.

- Bertholet, Auguste (2021). "Constant, Sismondi et la Pologne". Annales Benjamin Constant. 46: 80–81.

- Smith, A., 1976, vol. 2a, p. 10, idem

- Smith, A., 1976, vol. 1, p. 10, para. 4

- The Glasgow edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith, 1982, 6 volumes

- "Adam Smith – Jonathan Swift". University of Winchester. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- 100 Best Scottish Books, Adam Smith Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 31 January 2012

- L.Seabrooke (2006). "Global Standards of Market Civilization". p. 192. Taylor & Francis 2006

- Stigler, George J. (1976). "The Successes and Failures of Professor Smith," Journal of Political Economy, 84(6), pp. 1199–1213 [1202]. Also published as Selected Papers, No. 50 (PDF), Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago.

- Samuelson, Paul A. (1977). "A Modern Theorist's Vindication of Adam Smith," American Economic Review, 67(1), p. 42. Reprinted in J.C. Wood, ed., Adam Smith: Critical Assessments, pp. 498–509. Preview. Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Schumpeter History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 185.

- Roemer, J.E. (1987). "Marxian Value Analysis". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, 383.

- Mandel, Ernest (1987). "Marx, Karl Heinrich", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics v. 3, pp. 372, 376.

- Marshall, Alfred; Marshall, Mary Paley (1879). The Economics of Industry. p. 2. ISBN 978-1855065475. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Jevons, W. Stanley (1879). The Theory of Political Economy (2nd ed.). p. xiv. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Clark, B. (1998). Political-economy: A comparative approach, 2nd ed., Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 32.

- Campus, Antonietta (1987). "Marginalist Economics", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, p. 320

- Smith 1977, §Book I, Chapter 2

- "The Vanity of the Philosopher: From Equality to Hierarchy" in Postclassical Economics Archived 4 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- The Wealth of Nations, Book 5, Chapter 1, Part 2

- Pitts, Jennifer (2005). A Turn to Empire: The Rise of Imperial Liberalism in Britain and France. Princeton University Press. pp. 39–58. ISBN 978-1-4008-2663-6.

- E.A. Benians, 'Adam Smith's project of an empire', Cambridge Historical Journal 1 (1925): 249–283

- Anthony Howe, Free trade and liberal England, 1846–1946 (Oxford, 1997)

- J. Shield Nicholson, A project of empire: a critical study of the economics of imperialism, with special reference to the ideas of Adam Smith (London, 1909)

- Marc-William Palen, “Adam Smith as Advocate of Empire, c. 1870–1932,” Archived 22 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Historical Journal 57: 1 (March 2014): 179–198.

- "Clydesdale 50 Pounds, 1981". Ron Wise's Banknoteworld. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- "Current Banknotes : Clydesdale Bank". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- "Smith replaces Elgar on £20 note". BBC. 29 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- Blackley, Michael (26 September 2007). "Adam Smith sculpture to tower over Royal Mile". Edinburgh Evening News.

- Fillo, Maryellen (13 March 2001). "CCSU welcomes a new kid on the block". The Hartford Courant.

- Kelley, Pam (20 May 1997). "Piece at UNCC is a puzzle for Charlotte, artist says". The Charlotte Observer.

- Shaw-Eagle, Joanna (1 June 1997). "Artist sheds new light on sculpture". The Washington Times.

- "Adam Smith's Spinning Top". Ohio Outdoor Sculpture Inventory. Archived from the original on 5 February 2005. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- "The restoration of Panmure House". Archived from the original on 22 January 2012.

- "Adam Smith's Home Gets Business School Revival". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "The Adam Smith Society". The Adam Smith Society. Archived from the original on 21 July 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- Choi, Amy (4 March 2014). "Defying Skeptics, Some Business Schools Double Down on Capitalism". Bloomberg Business News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "Who We Are: The Adam Smith Society". April 2016. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "The Australian Adam Smith Club". Adam Smith Club. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Levy, David (June 1992). "Interview with Milton Friedman". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- "FRB: Speech, Greenspan – Adam Smith – 6 February 2005". Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- "Adam Smith: Web Junkie". Forbes. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- Stein, Herbert (6 April 1994). "Board of Contributors: Remembering Adam Smith". The Wall Street Journal Asia: A14.

- Brown, Vivienne; Pack, Spencer J.; Werhane, Patricia H. (January 1993). "Untitled review of 'Capitalism as a Moral System: Adam Smith's Critique of the Free Market Economy' and 'Adam Smith and his Legacy for Modern Capitalism'". The Economic Journal. 103 (416): 230–232. doi:10.2307/2234351. JSTOR 2234351.

- Smith 1977, bk. V, ch. 2

- "Market Man". The New Yorker. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- The Wealth of Nations, V.ii.k.1

- The Wealth of Nations, IV.ix.51

- Smith 1977, bk. V

- Smith, A., 1976, The Glasgow edition, vol. 2a, p. 468.

- The Wealth of Nations, IV.ii.39

- Viner, Jacob (April 1927). "Adam Smith and Laissez-faire". The Journal of Political Economy. 35 (2): 198–232. doi:10.1086/253837. JSTOR 1823421. S2CID 154539413.

- Klein, Daniel B. (2008). "Toward a Public and Professional Identity for Our Economics". Econ Journal Watch. 5 (3): 358–372. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- Klein, Daniel B. (2009). "Desperately Seeking Smithians: Responses to the Questionnaire about Building an Identity". Econ Journal Watch. 6 (1): 113–180. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- Buchholz, Todd (December 1990). pp. 38–39.

- Martin, Christopher. "Adam Smith and Liberal Economics: Reading the Minimum Wage Debate of 1795–96," Econ Journal Watch 8(2): 110–125, May 2011 Archived 28 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- A Smith, Wealth of Nations (1776) Book I, ch 8

Bibliography

- Benians, E. A. (1925). "II. Adam Smith's Project of an Empire". Cambridge Historical Journal. 1 (3): 249–283. doi:10.1017/S1474691300001062.

- Bonar, James, ed. (1894). A Catalogue of the Library of Adam Smith. London: Macmillan. OCLC 2320634 – via Internet Archive.

- Buchan, James (2006). The Authentic Adam Smith: His Life and Ideas. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06121-3.

- Buchholz, Todd (1999). New Ideas from Dead Economists: An Introduction to Modern Economic Thought. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028313-7.

- Bussing-Burks, Marie (2003). Influential Economists. Minneapolis: The Oliver Press. ISBN 1-881508-72-2.

- Campbell, R.H.; Skinner, Andrew S. (1985). Adam Smith. Routledge. ISBN 0-7099-3473-4.

- Coase, R.H. (October 1976). "Adam Smith's View of Man". The Journal of Law and Economics. 19 (3): 529–546. doi:10.1086/466886. S2CID 145363933.

- Helbroner, Robert L. The Essential Adam Smith. ISBN 0-393-95530-3

- Nicholson, J. Shield (1909). A project of empire;a critical study of the economics of imperialism, with special reference to the ideas of Adam Smith. Macmillan and co., limited. hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t4th8nc9p.

- Otteson, James R. (2002). Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01656-8

- Palen, Marc-William (2014). "Adam Smith as Advocate of Empire, c. 1870–1932" (PDF). The Historical Journal. 57: 179–198. doi:10.1017/S0018246X13000101. S2CID 159524069. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2020.

- Rae, John (1895). Life of Adam Smith. London & New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-7222-2658-6. Retrieved 14 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Ross, Ian Simpson (1995). The Life of Adam Smith. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-828821-2.

- Ross, Ian Simpson (2010). The Life of Adam Smith (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Skousen, Mark (2001). The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of Great Thinkers. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0480-9.

- Smith, Adam (1977) [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76374-9.

- Smith, Adam (1982) [1759]. D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie (ed.). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Liberty Fund. ISBN 0-86597-012-2.

- Smith, Adam (2002) [1759]. Knud Haakonssen (ed.). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59847-8.

- Smith, Vernon L. (July 1998). "The Two Faces of Adam Smith". Southern Economic Journal. 65 (1): 2–19. doi:10.2307/1061349. JSTOR 1061349. S2CID 154002759.

- Tribe, Keith; Mizuta, Hiroshi (2002). A Critical Bibliography of Adam Smith. Pickering & Chatto. ISBN 978-1-85196-741-4.

- Viner, Jacob (1991). Douglas A. Irwin (ed.). Essays on the Intellectual History of Economics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04266-7.

Further reading

| Library resources about Adam Smith |

| By Adam Smith |

|---|

- Butler, Eamonn (2007). Adam Smith – A Primer. Institute of Economic Affairs. ISBN 978-0-255-36608-3.

- Cook, Simon J. (2012). "Culture & Political Economy: Adam Smith & Alfred Marshall". Tabur.

- Copley, Stephen (1995). Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations: New Interdisciplinary Essays. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3943-6.

- Glahe, F. (1977). Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations: 1776–1976. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-082-0.

- Haakonssen, Knud (2006). The Cambridge Companion to Adam Smith. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77924-3.

- Hamowy, Ronald (2008). "Smith, Adam (1723–1790)". The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 470–472. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n287. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Hardwick, D. and Marsh, L. (2014). Propriety and Prosperity: New Studies on the Philosophy of Adam Smith. Palgrave Macmillan

- Hollander, Samuel (1973). Economics of Adam Smith. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6302-0.

- McLean, Iain (2006). Adam Smith, Radical and Egalitarian: An Interpretation for the 21st Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2352-3.

- Milgate, Murray & Stimson, Shannon. (2009). After Adam Smith: A Century of Transformation in Politics and Political Economy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14037-7.

- Muller, Jerry Z. (1995). Adam Smith in His Time and Ours. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00161-8.

- Norman, Jesse (2018). Adam Smith: What He Thought, and Why It Matters. Allen Lane.

- O'Rourke, P.J. (2006). On The Wealth of Nations. Grove/Atlantic Inc. ISBN 0-87113-949-9.

- Otteson, James (2002). Adam Smith's Marketplace of Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01656-8.

- Otteson, James (2013). Adam Smith. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-9013-0.

- Phillipson, Nicholas (2010). Adam Smith: An Enlightened Life, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-16927-0, 352 pages; scholarly biography

- Pichet, Éric (2004). Adam Smith, je connais !, French biography. ISBN 978-2843720406

- Vianello, F. (1999). "Social accounting in Adam Smith", in: Mongiovi, G. and Petri F. (eds.), Value, Distribution and capital. Essays in honour of Pierangelo Garegnani, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-14277-6.

- Winch, Donald (2007) [2004]. "Smith, Adam". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25767. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wolloch, N. (2015). "Symposium on Jack Russell Weinstein's Adam Smith's Pluralism: Rationality, Education and the Moral Sentiments". Cosmos + Taxis

- "Adam Smith and Empire: A New Talking Empire Podcast," Imperial & Global Forum, 12 March 2014.

External links

- Adam Smith at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Adam Smith at Open Library

- Works by Adam Smith at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Adam Smith at Internet Archive

- Works by Adam Smith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- References to Adam Smith in historic European newspapers

- "Adam Smith". Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009. at the Adam Smith Institute