Theodor Mommsen

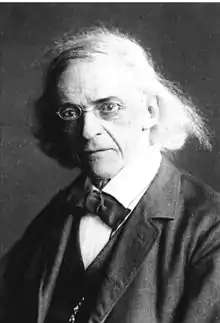

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (German pronunciation: [ˈteːodoːɐ̯ ˈmɔmzn̩] (![]() listen); 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist.[1] He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. He received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Literature for being "the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work, A History of Rome", after having been nominated by 18 members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.[2][3] He was also a prominent German politician, as a member of the Prussian and German parliaments. His works on Roman law and on the law of obligations had a significant impact on the German civil code.

listen); 30 November 1817 – 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist.[1] He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. He received the 1902 Nobel Prize in Literature for being "the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work, A History of Rome", after having been nominated by 18 members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.[2][3] He was also a prominent German politician, as a member of the Prussian and German parliaments. His works on Roman law and on the law of obligations had a significant impact on the German civil code.

Theodor Mommsen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen 30 November 1817 Garding, Duchy of Schleswig, German Confederation |

| Died | 1 November 1903 (aged 85) Charlottenburg, Brandenburg, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Education | Gymnasium Christianeum University of Kiel |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite (civil class) Nobel Prize in Literature 1902 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Classical scholar, jurist, ancient historian |

| Institutions | University of Leipzig University of Zurich University of Breslau University of Berlin |

| Notable students | Wilhelm Dilthey Eduard Schwartz Otto Seeck |

Life

Mommsen was born to German parents in Garding in the Duchy of Schleswig in 1817, then ruled by the king of Denmark, and grew up in Bad Oldesloe in Holstein, where his father was a Lutheran minister. He studied mostly at home, though he attended the Gymnasium Christianeum in Altona for four years. He studied Greek and Latin and received his diploma in 1837. As he could not afford to study at Göttingen, he enrolled at the University of Kiel.

Mommsen studied jurisprudence at Kiel from 1838 to 1843, finishing his studies with the degree of Doctor of Roman Law. During this time he was the roommate of Theodor Storm, who was later to become a renowned poet. Together with Mommsen's brother Tycho, the three friends even published a collection of poems (Liederbuch dreier Freunde). Thanks to a royal Danish grant, Mommsen was able to visit France and Italy to study preserved classical Roman inscriptions. During the revolution of 1848 he worked as a war correspondent in then-Danish Rendsburg, supporting the German annexation of Schleswig-Holstein and a constitutional reform. Having been forced to leave the country by the Danes, he became a professor of law in the same year at the University of Leipzig. When Mommsen protested against the new constitution of Saxony in 1851, he had to resign. However, the next year he obtained a professorship in Roman law at the University of Zurich and then spent a couple of years in exile. In 1854 he became a professor of law at the University of Breslau where he met Jakob Bernays. Mommsen became a research professor at the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1857. He later helped to create and manage the German Archaeological Institute in Rome.

In 1858 Mommsen was appointed a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin, and he also became professor of Roman History at the University of Berlin in 1861, where he held lectures up to 1887. Mommsen received high recognition for his academic achievements: foreign membership of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1859,[4] the Prussian medal Pour le Mérite in 1868, honorary citizenship of Rome, elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1870,[5] and the Nobel prize in literature in 1902 for his main work Römische Geschichte (Roman History). (He is one of the very few non-fiction writers to receive the Nobel prize in literature.)[6]

In 1873, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society.[7]

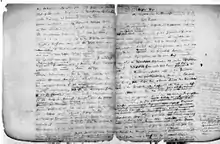

At 2 a.m. on 7 July 1880 a fire occurred in the upper floor workroom-library of Mommsen's house at Marchstraße 6 in Berlin.[9][10][11] After being burned while attempting to remove valuable papers, he was restrained from returning to the blazing house. Several old manuscripts were burnt to ashes, including Manuscript 0.4.36, which was on loan from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge.[12] There is information that the important Manuscript of Jordanes from Heidelberg University library was burnt.[13] Two other important manuscripts, from Brussels and Halle, were also destroyed.[14]

Mommsen was an indefatigable worker who rose at five to do research in his library. People often saw him reading whilst walking in the streets.[15]

Mommsen had sixteen children with his wife Marie (daughter of the publisher and editor Karl Reimer of Leipzig). Their oldest daughter Maria married Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, the great Classics scholar. Their grandson Theodor Ernst Mommsen (1905–1958) became a professor of medieval history in the United States. Two of the great-grandsons, Hans Mommsen and Wolfgang Mommsen, were German historians.

Scholarly works

Mommsen published over 1,500 works, and effectively established a new framework for the systematic study of Roman history. He pioneered epigraphy, the study of inscriptions in material artifacts. Although the unfinished History of Rome, written early in his career, has long been widely considered as his main work, the work most relevant today is, perhaps, the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, a collection of Roman inscriptions he contributed to the Berlin Academy.[16]

- Mommsen's History of Rome, his most famous work, appeared as three volumes in 1854, 1855, and 1856. It expounded Roman history up to the end of the Roman republic and the rule of Julius Caesar. Since Mommsen admired Caesar, he felt unable to describe the death of his hero. He closely compared the political thought and terminology of the ancient Republic, especially during its last century, with the situation of his own time, e.g., the nation-state, democracy and incipient imperialism. It is one of the great classics of historical works. Mommsen never wrote a promised next volume to recount subsequent events during the imperial period, i.e., a volume 4, although demand was high for a continuation.[17] Immediately very popular and acknowledged internationally by classical scholars, the work also quickly received criticism.[18]

- The Provinces of the Roman Empire from Caesar to Diocletian (1885), published as volume 5 of his History of Rome, is a description of all Roman regions during the early imperial period.

- Roman Chronology to the Time of Caesar (1858) written with his brother August Mommsen.

- Roman Constitutional Law (1871–1888). This systematic treatment of Roman constitutional law in three volumes has been of importance for research on ancient history.

.jpg.webp)

- Roman Criminal Law (1899)

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, lead editor and editor (1861, et seq.)

- Digesta (of Justinian), editor (1866–1870, two volumes)

- Iordanis Romana et Getica (1882) was Mommsen's critical edition of Jordanes' The Origin and Deeds of the Goths and has subsequently come to be generally known simply as Getica.

- Codex Theodosianus, editor (1905, posthumous)

- Monumentum Ancyranum

- More than 1,500 further studies and treatises on single issues.

A bibliography of over 1,000 of his works is given by Zangemeister in Mommsen als Schriftsteller (1887; continued by Jacobs, 1905).

Mommsen as editor and organiser

While he was secretary of the Historical-Philological Class at the Berlin Academy (1874–1895), Mommsen organised countless scientific projects, mostly editions of original sources.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

At the beginning of his career, when he published the inscriptions of the Neapolitan Kingdom (1852), Mommsen already had in mind a collection of all known ancient Latin inscriptions. He received additional impetus and training from Bartolomeo Borghesi of San Marino. The complete Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum would consist of sixteen volumes. Fifteen of them appeared in Mommsen's lifetime and he wrote five of them himself. The basic principle of the edition (contrary to previous collections) was the method of autopsy, according to which all copies (i.e., modern transcriptions) of inscriptions were to be checked and compared to the original.

Further editions and research projects

Mommsen published the fundamental collections in Roman law: the Corpus Iuris Civilis and the Codex Theodosianus. Furthermore, he played an important role in the publication of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, the edition of the texts of the Church Fathers, the limes romanus (Roman frontiers) research and countless other projects.

Mommsen as politician

Mommsen was a delegate to the Prussian House of Representatives from 1863 to 1866 and again from 1873 to 1879, and delegate to the Reichstag from 1881 to 1884, at first for the liberal German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei), later for the National Liberal Party, and finally for the Secessionists. He was very concerned with questions about academic and educational policies and held national positions. Although he had supported German Unification, he was disappointed with the politics of the German Empire and he was quite pessimistic about its future. Mommsen strongly disagreed with Otto von Bismarck about social policies in 1881, advising collaboration between Liberals and Social Democrats and using such strong language that he narrowly avoided prosecution.

As a Liberal nationalist Mommsen favored assimilation of ethnic minorities into German society, not exclusion.[19] In 1879, his colleague Heinrich von Treitschke began a political campaign against Jews (the so-called Berliner Antisemitismusstreit). Mommsen strongly opposed antisemitism and wrote a harsh pamphlet in which he denounced von Treitschke's views. Mommsen viewed a solution to antisemitism in voluntary cultural assimilation, suggesting that the Jews could follow the example of the people of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover and other German states, which gave up some of their special customs when integrating in Prussia.[20] Mommsen was a vehement spokesman for German nationalism, maintaining a militant attitude towards the Slavic nations, to the point of advocating the use of violence against them. In an 1897 letter to the Neue Freie Presse of Vienna, Mommsen called Czechs "apostles of barbarism" and wrote that "the Czech skull is impervious to reason, but it is susceptible to blows".[21][22]

Influence of Mommsen

Fellow Nobel Laureate (1925) Bernard Shaw cited Mommsen's interpretation of the last First Consul of the Republic, Julius Caesar, as one of the inspirations for his 1898 (1905 on Broadway) play, Caesar and Cleopatra.

Noted naval historian and theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan formulated the thesis for his magnum opus, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, while reading Mommsen's History of Rome.[23]

The playwright Heiner Müller wrote a 'performance text' entitled Mommsens Block (1993), inspired by the publication of Mommsen's fragmentary notes on the later Roman empire and by the East German government's decision to replace a statue of Karl Marx outside the Humboldt University of Berlin with one of Mommsen.[24]

There is a Gymnasium (academic high school) named for Mommsen in his hometown of Bad Oldesloe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. His birthplace Garding in the west of Schleswig styles itself "Mommsen-Stadt Garding".

Mark Twain

"One of the highpoints of Mark Twain's European tour of 1892 was a large formal banquet at the University of Berlin... . Mark Twain was an honored guest, seated at the head table with some twenty 'particularly eminent professors'; and it was from this vantage point that he witnessed the following incident..."[25] In Twain's own words:

When apparently the last eminent guest had long ago taken his place, again those three bugle-blasts rang out, and once more the swords leaped from their scabbards. Who might this late comer be? Nobody was interested to inquire. Still, indolent eyes were turned toward the distant entrance, and we saw the silken gleam and the lifted sword of a guard of honor plowing through the remote crowds. Then we saw that end of the house rising to its feet; saw it rise abreast the advancing guard all along like a wave. This supreme honor had been offered to no one before. There was an excited whisper at our table—'MOMMSEN!'—and the whole house rose. Rose and shouted and stamped and clapped and banged the beer mugs. Just simply a storm!

Then the little man with his long hair and Emersonian face edged his way past us and took his seat. I could have touched him with my hand—Mommsen!—think of it! ... I would have walked a great many miles to get a sight of him, and here he was, without trouble or tramp or cost of any kind. Here he was clothed in a titanic deceptive modesty which made him look like other men.[26]

Bibliography

- Mommsen, Theodor. Rome, from earliest times to 44 B. C. (1906) online

- Mommsen, Theodor. History of Rome: Volume 1 (1894) online edition

- Mommsen, Theodor. History of Rome: Volume 2 (1871) online edition

- Mommsen, Theodor. History of Rome: Volume 3 (1891) online edition

- Mommsen, Theodor. History of Rome: Volume 4 (1908) online edition

- Mommsen, Theodor: Römische Geschichte. 8 Volumes. dtv, München 2001. ISBN 3-423-59055-6

See also

- Statue of Theodor Mommsen, Humboldt University of Berlin

References

- "Theodor Mommsen". www.nndb.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1902". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Th. Mommsen (1817–1903)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "MemberListM". americanantiquarian.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Until 2007, when Doris Lessing won the Literature Prize, Mommsen was the oldest person to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature

- "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "Archiv der BBAW, 47/1 fol. 6; Phönix aus der Asche" (PDF). p. 57.

- Mentzel-Reuters, Arno; Mersiowsky, Mark; Orth, Peter; Rader, Olaf B. (2005). "Phönix aus der Asche – Theodor Mommsen und die Monumenta Germaniae Historica" (PDF). München and Berlin: Mgh-bibliothek.de. p. 53.

- Vossische Zeitung 12 July 1880 (Nr. 192) in column "Lokales"

- "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- quote: Another manuscript is beyond recall; namely, 0.4.36, which was borrowed by Professor Theodor Mommsen and perished in the lamentable fire at his house in 1880. It was not, apparently, an indispensable or even a very important authority for the texts (Jordanes, the Antonine Itinerary, etc.) which it contained, and other copies of its archetype are yet in being: still, the loss of it is very regrettable; M. R. James' "The Western Manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge: a Descriptive Catalogue". Archived from the original on 12 July 2009.

- "Quote: Der größte Verlust war eine frühmittelalterliche Jordanes-Handschrift aus der Heidelberger Universitätsbibliothek" (PDF). p. 53.

- ...vor allem zwei aus Brüssel und Halle entlehnte Handschriften.

- "Apart from any actual learning, the deepest impression that I carried away from my first Semester in Berlin was a sense of the pervading enthusiasm for Wissenschaft. I was also astonished at the high standard of industry both among the Seniors and the Juniors whom I mixed up with. And I could not help feeling that our steadiest workers among my Oxford undergraduate friends were only casual 'half-timers' by comparison. What was still more stimulating was the whole-hearted and unquestioning reverence for learning broadcast through the academic circles and extending even to the outside public. I had a striking proof of this: as an illustration of national character, the anecdote is worth recording. Living in Berlin at some distance from the university, I used to go in every morning by the same early tram: and at last noting that I was a foreigner of regular habits, the affable and chatty tramway conductor used to point out to me the objects worthy of interest by the way (Sehenswürdigkeiten—a crisp Teutonic word). One morning as we approached a halting-place, I saw a little old gentleman with silvery hair leaning against a lamp-post and holding a large open volume near to his short-sighted eyes, oblivious of the uproar around: the conductor sprang down towards him, and tapping him reverentially on the shoulder conducted him gently to the tram and settled him in his place. Immediately the old gentleman buried himself again up to the eyes in his tome. The conductor, proud of this new Sehenswürdigkeit, whispered to me in an awed voice: 'Da ist der berühmte Herr Professor Mommsen; er verliert kein Moment'! ('There is the famous Professor Mr Mommsen; he never loses a moment!' referring to his absorption in his book). I felt thrilled, not by Mommsen, but by this deep revelation of the national soul, an illiterate conductor knowing of Mommsen at all, knowing that he was academically famous, being proud of having him in his tram, and proud that he 'never lost a moment' for study." — Farnell, Lewis R. (1934). An Oxonian Looks Back. London: Martin Hopkinson, p. 88.

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Theodor Mommsen". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014.

- Notes taken between 1882 and 1886 of his lectures on the Roman Empire were discovered nearly a century later and in 1992 were published under the title A History of Rome Under the Emperors.

- His terse style was called journalistic. His transparent comparison of ancient to modern politics was said to distort. In 1931 Egon Friedell summed it up, that in his hands "Crassus becomes a speculator in the manner of Louis Philippe, the brothers Gracchus are Socialist leaders, and the Gauls are Indians, etc." Friedell, Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit, v3 p270. Cf., Mommsen's History of Rome.

- Daniel Ziblatt (2008). Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism. Princeton U.P. p. 54. ISBN 978-1400827244.

- "Prof. Mommsen and the Jews", from The Times, reprinted in The New York Times, 8 January 1881.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "An die Deutschen in Oesterreich". Neue Freie Presse – issue 11923. 31 October 1897.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer. From Sail to Stream: Recollections of Naval Life. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1907: 277

- Heiner Müller, Mommsen's Block. In A Heiner Müller Reader: Plays | Poetry | Prose. Ed. and trans. Carl Weber. PAJ Books Ser. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8018-6578-6. p.122-129.

- Saunder and Collins, "Introduction" to their edition of Mommsen's History of Rome (Meridian Books 1958), at 1–17, 1.

- Cited by Saunders and Collins, supra.

Further reading

- Carter, Jesse Benedict. "Theodor Mommsen," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. XCIII, 1904.

- Gay, Peter, and Victor G. Wexler, (eds). Historians at Work, Vol. III, 1975, pp. 271+

- Lionel Gossman, Orpheus Philologus: Bachofen versus Mommsen on the Study of Antiquity. American Philosophical Society, 1983. ISBN 1-4223-7467-X.

- Anthony Grafton. "Roman Monument" History Today September 2006 online.

- Mueller, G. H.. "Weber and Mommsen: non-Marxist materialism," British Journal of Sociology, (March 1986), 37(1), pp. 1–20 in JSTOR

- Whitman, Sidney, and Theodor Mommsen. "German Feeling toward England and America," North American Review, Vol. 170, No. 519 (Feb. 1900), pp. 240–243 online in JSTOR, an exchange of letters

- Krmnicek, Stefan (ed.). Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903) auf Medaillen und Plaketten. Sammlung des Instituts für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Tübingen (Von Krösus bis zu König Wilhelm. Neue Serie 2). Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen, Tübingen 2017, https://dx.doi.org/10.15496/publikation-19540.

External links

Media related to Theodor Mommsen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Theodor Mommsen at Wikimedia Commons Works by or about Theodor Mommsen at Wikisource

Works by or about Theodor Mommsen at Wikisource Quotations related to Theodor Mommsen at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Theodor Mommsen at Wikiquote- List of works

- Theodor Mommsen on Nobelprize.org

- Petri Liukkonen. "Theodor Mommsen". Books and Writers

- Theodor Mommsen biography from the Mommsen family website

- Home page of Garding municipality

- Theodor Mommsen History of Rome

- Works by Theodor Mommsen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Theodor Mommsen at Internet Archive

- Works by Theodor Mommsen at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Römische Geschichte (Roman History) at German Project Gutenberg: E-Text of Vol. 1 – 5 & 8 (vol. 6 & 7 do not exist) in German.

- The Project Gutenberg eBook, The History of Rome (Volumes 1-5), by Theodor Mommsen, Translated by William Purdie Dickson