Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (/ˈɡaɪəs ... ˈsiːzər/; Latin: [ˈɡaːiʊs ˈjuːliʊs ˈkae̯sar]; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Gaius Julius Caesar | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 12 July 100 BC[1] Rome, Italy |

| Died | 15 March 44 BC (aged 55) Rome, Italy |

| Cause of death | Assassination (stab wounds) |

| Resting place | Temple of Caesar, Rome 41.891943°N 12.486246°E |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Office |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Partner | Cleopatra |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Military career | |

| Years | 81–45 BC |

| Conflicts |

|

| Awards | Civic Crown |

In 60 BC, Caesar, Crassus and Pompey formed the First Triumvirate, an informal political alliance that dominated Roman politics for several years. Their attempts to amass power as Populares were opposed by the Optimates within the Roman Senate, among them Cato the Younger with the frequent support of Cicero. Caesar rose to become one of the most powerful politicians in the Roman Republic through a string of military victories in the Gallic Wars, completed by 51 BC, which greatly extended Roman territory. During this time he both invaded Britain and built a bridge across the Rhine river. These achievements and the support of his veteran army threatened to eclipse the standing of Pompey, who had realigned himself with the Senate after the death of Crassus in 53 BC. With the Gallic Wars concluded, the Senate ordered Caesar to step down from his military command and return to Rome. In 49 BC, Caesar openly defied the Senate's authority by crossing the Rubicon and marching towards Rome at the head of an army.[2] This began Caesar's civil war, which he won, leaving him in a position of near unchallenged power and influence in 45 BC.

After assuming control of government, Caesar began a program of social and governmental reforms, including the creation of the Julian calendar. He gave citizenship to many residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He initiated land reform and support for veterans. He centralized the bureaucracy of the Republic and was eventually proclaimed "dictator for life" (dictator perpetuo). His populist and authoritarian reforms angered the elites, who began to conspire against him. On the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, Caesar was assassinated by a group of rebellious senators led by Brutus and Cassius, who stabbed him to death.[3][4] A new series of civil wars broke out and the constitutional government of the Republic was never fully restored. Caesar's great-nephew and adopted heir Octavian, later known as Augustus, rose to sole power after defeating his opponents in the last civil war of the Roman Republic. Octavian set about solidifying his power, and the era of the Roman Empire began.

Caesar was an accomplished author and historian as well as a statesman; much of his life is known from his own accounts of his military campaigns. Other contemporary sources include the letters and speeches of Cicero and the historical writings of Sallust. Later biographies of Caesar by Suetonius and Plutarch are also important sources. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history.[5] His cognomen was subsequently adopted as a synonym for "Emperor"; the title "Caesar" was used throughout the Roman Empire, giving rise to modern cognates such as Kaiser and Tsar. He has frequently appeared in literary and artistic works, and his political philosophy, known as Caesarism, has inspired politicians into the modern era.

Early life and career

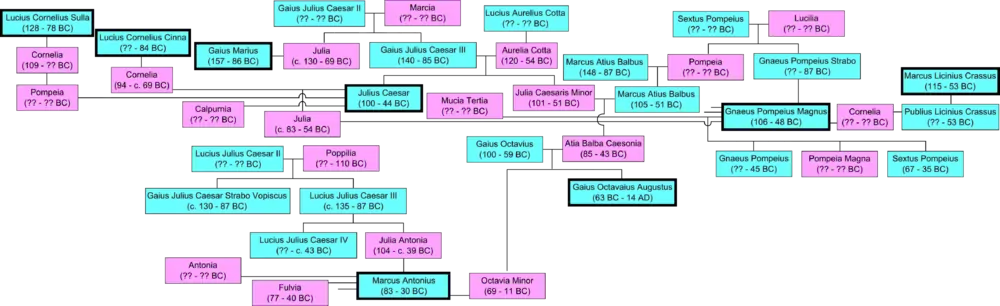

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a patrician family, the gens Julia, which claimed descent from Julus, son of the legendary Trojan prince Aeneas, supposedly the son of the goddess Venus.[6] The Julii were of Alban origin, mentioned as one of the leading Alban houses, which settled in Rome around the mid-7th century BC, following the destruction of Alba Longa. They were granted patrician status, along with other noble Alban families.[7] The Julii also existed at an early period at Bovillae, evidenced by a very ancient inscription on an altar in the theatre of that town, which speaks of their offering sacrifices according to the lege Albana, or Alban rites.[8][9][10] The cognomen "Caesar" originated, according to Pliny the Elder, with an ancestor who was born by Caesarean section (from the Latin verb "to cut", caedere, caes-).[11] The Historia Augusta suggests three alternative explanations: that the first Caesar had a thick head of hair ("caesaries"); that he had bright grey eyes ("oculis caesiis"); or that he killed an elephant ("caesai" in Moorish) in battle.[12]

Despite their ancient pedigree, the Julii Caesares were not especially politically influential, although they had enjoyed some revival of their political fortunes in the early 1st century BC.[13] Caesar's father, also called Gaius Julius Caesar, governed the province of Asia,[14] and his sister Julia, Caesar's aunt, married Gaius Marius, one of the most prominent figures in the Republic.[15] His mother, Aurelia, came from an influential family. Little is recorded of Caesar's childhood.[16]

In 85 BC, Caesar's father died suddenly,[17] making Caesar the head of the family at the age of 16. His coming of age coincided with the civil wars of his uncle Gaius Marius and his rival Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Both sides carried out bloody purges of their political opponents whenever they were in the ascendancy. Marius and his ally Lucius Cornelius Cinna were in control of the city when Caesar was nominated as the new flamen Dialis (high priest of Jupiter),[18] and he was married to Cinna's daughter Cornelia.[19][20]

Following Sulla's final victory, however, Caesar's connections to the old regime made him a target for the new one. He was stripped of his inheritance, his wife's dowry, and his priesthood, but he refused to divorce Cornelia and was instead forced to go into hiding.[21] The threat against him was lifted by the intervention of his mother's family, which included supporters of Sulla, and the Vestal Virgins. Sulla gave in reluctantly and is said to have declared that he saw many a Marius in Caesar.[16] The loss of his priesthood had allowed him to pursue a military career, as the high priest of Jupiter was not permitted to touch a horse, sleep three nights outside his own bed or one night outside Rome, or look upon an army.[22]

Caesar felt that it would be much safer far away from Sulla should the dictator change his mind, so he left Rome and joined the army, serving under Marcus Minucius Thermus in Asia and Servilius Isauricus in Cilicia. He served with distinction, winning the Civic Crown for his part in the Siege of Mytilene. He went on a mission to Bithynia to secure the assistance of King Nicomedes's fleet, but he spent so long at Nicomedes' court that rumours arose of an affair with the king, which Caesar vehemently denied for the rest of his life.[23]

Hearing of Sulla's death in 78 BC, Caesar felt safe enough to return to Rome. He lacked means since his inheritance was confiscated, but he acquired a modest house in Subura, a lower-class neighbourhood of Rome.[24] He turned to legal advocacy and became known for his exceptional oratory accompanied by impassioned gestures and a high-pitched voice,[25] and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption.

On the way across the Aegean Sea,[26] Caesar was kidnapped by pirates and held prisoner.[27][28] He maintained an attitude of superiority throughout his captivity. The pirates demanded a ransom of 20 talents of silver, but he insisted that they ask for 50.[29][30] Caesar was relaxed and familiar with his captors, and (seemingly) joked that after his release he would raise a fleet, pursue and capture the pirates, and crucify them while alive.[31] After his ransom was paid he fulfilled this promise in full, apart from one detail – as a sign of leniency, he first had their throats cut. He was soon called back into military action in Asia, raising a band of auxiliaries to repel an incursion from the east.[32]

On his return to Rome, he was elected military tribune, a first step in a political career. He was elected quaestor in 69 BC,[33] and during that year he delivered the funeral oration for his aunt Julia, including images of her husband Marius, unseen since the days of Sulla, in the funeral procession. His wife Cornelia also died that year.[34] Caesar went to serve his quaestorship in Hispania after his wife's funeral, in the spring or early summer of 69 BC.[35] While there, he is said to have encountered a statue of Alexander the Great, and realised with dissatisfaction that he was now at an age when Alexander had the world at his feet, while he had achieved comparatively little. On his return in 67 BC,[36] he married Pompeia, a granddaughter of Sulla, whom he later divorced in 61 BC after her embroilment in the Bona Dea scandal.[37] In 65 BC, he was elected curule aedile, and staged lavish games that won him further attention and popular support.[38]

In 63 BC, he ran for election to the post of pontifex maximus, chief priest of the Roman state religion. He ran against two powerful senators. Accusations of bribery were made by all sides. Caesar won comfortably, despite his opponents' greater experience and standing.[39] Cicero was consul that year, and he exposed Catiline's conspiracy to seize control of the Republic; several senators accused Caesar of involvement in the plot.[40]

After serving as praetor in 62 BC, Caesar was appointed to govern Hispania Ulterior (the western part of the Iberian Peninsula) as propraetor,[41][42][43] though some sources suggest that he held proconsular powers.[44][45] He was still in considerable debt and needed to satisfy his creditors before he could leave. He turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus, the richest man in Rome. Crassus paid some of Caesar's debts and acted as guarantor for others, in return for political support in his opposition to the interests of Pompey. Even so, to avoid becoming a private citizen and thus open to prosecution for his debts, Caesar left for his province before his praetorship had ended. In Hispania, he conquered two local tribes and was hailed as imperator by his troops; he reformed the law regarding debts, and completed his governorship in high esteem.[46]

Caesar was acclaimed imperator in 60 BC (and again later in 45 BC). In the Roman Republic, this was an honorary title assumed by certain military commanders. After an especially great victory, army troops in the field would proclaim their commander imperator, an acclamation necessary for a general to apply to the Senate for a triumph. However, Caesar also wished to stand for consul, the most senior magistracy in the Republic. If he were to celebrate a triumph, he would have to remain a soldier and stay outside the city until the ceremony, but to stand for election he would need to lay down his command and enter Rome as a private citizen. He could not do both in the time available. He asked the Senate for permission to stand in absentia, but Cato blocked the proposal. Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship.[47]

Consulship and military campaigns

In 60 BC, Caesar sought election as consul for 59 BC, along with two other candidates. The election was sordid—even Cato, with his reputation for incorruptibility, is said to have resorted to bribery in favour of one of Caesar's opponents. Caesar won, along with conservative Marcus Bibulus.[48]

Caesar was already in Marcus Licinius Crassus' political debt, but he also made overtures to Pompey. Pompey and Crassus had been at odds for a decade, so Caesar tried to reconcile them. The three of them had enough money and political influence to control public business. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate ("rule of three men"), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter Julia.[49] Caesar also married again, this time Calpurnia, who was the daughter of another powerful senator.[50]

Caesar proposed a law for redistributing public lands to the poor—by force of arms, if need be—a proposal supported by Pompey and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, a move which intimidated the triumvirate's opponents. Bibulus attempted to declare the omens unfavourable and thus void the new law, but he was driven from the forum by Caesar's armed supporters. Bibulus' lictors had their fasces broken, two high magistrates accompanying him were wounded, and he had a bucket of excrement thrown over him. In fear of his life, he retired to his house for the rest of the year, issuing occasional proclamations of bad omens. These attempts proved ineffective in obstructing Caesar's legislation. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as "the consulship of Julius and Caesar".[51]

When Caesar was first elected, the aristocracy tried to limit his future power by allotting the woods and pastures of Italy, rather than the governorship of a province, as his military command duty after his year in office was over.[52] With the help of political allies, Caesar secured passage of the lex Vatinia, granting him governorship over Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy) and Illyricum (northwest Balkans).[53] At the instigation of Pompey and his father-in-law Piso, Transalpine Gaul (southern France) was added later after the untimely death of its governor, giving him command of four legions.[53] The term of his governorship, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the usual one.[54][55] When his consulship ended, Caesar narrowly avoided prosecution for the irregularities of his year in office, and quickly left for his province.[56]

Conquest of Gaul

Caesar was still deeply in debt, but there was money to be made as a governor, whether by extortion[57] or by military adventurism. Caesar had four legions under his command, two of his provinces bordered on unconquered territory, and parts of Gaul were known to be unstable. Some of Rome's Gallic allies had been defeated by their rivals at the Battle of Magetobriga, with the help of a contingent of Germanic tribes. The Romans feared these tribes were preparing to migrate south, closer to Italy, and that they had warlike intent. Caesar raised two new legions and defeated these tribes.[58]

In response to Caesar's earlier activities, the tribes in the north-east began to arm themselves. Caesar treated this as an aggressive move and, after an inconclusive engagement against the united tribes, he conquered the tribes piecemeal. Meanwhile, one of his legions began the conquest of the tribes in the far north, directly opposite Britain.[59] During the spring of 56 BC, the Triumvirs held a conference, as Rome was in turmoil and Caesar's political alliance was coming undone. The Luca Conference renewed the First Triumvirate and extended Caesar's governorship for another five years.[60] The conquest of the north was soon completed, while a few pockets of resistance remained.[61] Caesar now had a secure base from which to launch an invasion of Britain.

In 55 BC, Caesar repelled an incursion into Gaul by two Germanic tribes, and followed it up by building a bridge across the Rhine and making a show of force in Germanic territory, before returning and dismantling the bridge. Late that summer, having subdued two other tribes, he crossed into Britain, claiming that the Britons had aided one of his enemies the previous year, possibly the Veneti of Brittany.[62] His knowledge of Britain was poor, and although he gained a beachhead on the coast, he could not advance further. He raided out from his beachhead and destroyed some villages, then returned to Gaul for the winter.[63] He returned the following year, better prepared and with a larger force, and achieved more. He advanced inland, and established a few alliances, but poor harvests led to widespread revolt in Gaul, forcing Caesar to leave Britain for the last time.[64]

Though the Gallic tribes were just as strong as the Romans militarily, the internal division among the Gauls guaranteed an easy victory for Caesar. Vercingetorix's attempt in 52 BC to unite them against Roman invasion came too late.[65][66] He proved an astute commander, defeating Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia, but Caesar's elaborate siege-works at the Battle of Alesia finally forced his surrender.[67] Despite scattered outbreaks of warfare the following year,[68] Gaul was effectively conquered. Plutarch claimed that during the Gallic Wars the army had fought against three million men (of whom one million died, and another million were enslaved), subjugated 300 tribes, and destroyed 800 cities.[69] The casualty figures are disputed by modern historians.[70]

Civil war

While Caesar was in Britain his daughter Julia, Pompey's wife, had died in childbirth. Caesar tried to re-secure Pompey's support by offering him his great-niece in marriage, but Pompey declined. In 53 BC, Crassus was killed leading a failed invasion of Parthia. Due to uncontrolled political violence in the city, Pompey was appointed sole consul in 52 as an emergency measure.[71] That year, a "Law of the Ten Tribunes" was passed, giving Caesar the right to stand for a consulship in absentia.[72]

.jpg.webp)

From the period 52 to 49 BC, trust between Caesar and Pompey disintegrated.[73] In 51 BC, the consul Marcellus proposed recalling Caesar, arguing that his provincia (here meaning "task") – due to his victory – in Gaul was complete; the proposal was vetoed.[74][75] That year, it seemed that the conservatives around Cato in the Senate would seek to enlist Pompey to force Caesar to return from Gaul without honours or a second consulship.[76] Pompey, however, at the time intended to go to Spain;[76] Cato, Bibulus, and their allies, however, were successful in winning Pompey over to take a hard line against Caesar's continued command.[77]

As 50 BC progressed, fears of civil war grew; both Caesar and his opponents started building up troops in southern Gaul and northern Italy, respectively.[78] In the autumn, Cicero and others sought disarmament by both Caesar and Pompey, and on 1 December 50 BC this was formally proposed in the Senate.[79] It received overwhelming support – 370 to 22 – but was not passed when one of the consuls dissolved the Senate meeting.[80] At the start of 49 BC, Caesar's renewed offer that he and Pompey disarm was read to the Senate, which was rejected by the hardliners.[81] A later compromise given privately to Pompey was also rejected at their insistence.[82] On 7 January, his supportive tribunes were driven from Rome; the Senate then declared Caesar an enemy and it issued its senatus consultum ultimum.[83]

There is scholarly disagreement as to the specific reasons why Caesar marched on Rome. A popular theory is that Caesar was in a position where he was forced to choose between prosecution and exile or civil war.[84] Whether Caesar actually would have been prosecuted and convicted is debated. Some scholars believe the possibility of successful prosecution was extremely unlikely.[85][86] Caesar's main objectives were to secure a second consulship and a triumph. He feared that his opponents – then holding both consulships for 50 BC – would reject his candidacy or refuse to ratify an election he won.[87] This also was the core of his war justification: that Pompey and his allies were planning, by force if necessary (indicated in the expulsion of the tribunes[88]), to suppress the liberty of the Roman people to elect Caesar and honour his accomplishments.[89]

Around 10 or 11 January 49 BC,[90][91] in response to the Senate's "final decree",[92] Caesar crossed the Rubicon – the river defining the northern boundary of Italy – with a single legion, the Legio XIII Gemina, and ignited civil war. Upon crossing the Rubicon, Caesar, according to Plutarch and Suetonius, is supposed to have quoted the Athenian playwright Menander, in Greek, "the die is cast".[93] Erasmus, however, notes that the more accurate Latin translation of the Greek imperative mood would be "alea iacta esto", let the die be cast.[94] Pompey and many senators fled south, believing that Caesar was marching quickly for Rome.[95] Caesar, after capturing communication routes to Rome, paused and opened negotiations, but they fell apart amid mutual distrust.[96] Caesar responded by advancing south, seeking to capture Pompey to force a conference.[97]

Pompey managed to escape Italy from Brundisium before Caesar could capture him. Heading for Hispania, Caesar left Italy under the control of Mark Antony. After an astonishing 27-day march, Caesar defeated Pompey's lieutenants, then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Illyria, where, on 10 July 48 BC in the battle of Dyrrhachium, Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat. In an exceedingly short engagement later that year, he decisively defeated Pompey at Pharsalus, Greece, on 9 August 48 BC.[98]

In Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator,[101] with Antony as his Master of the Horse (second in command); Caesar presided over his own election to a second consulship and then, after 11 days, resigned this dictatorship.[101][102] Caesar then pursued Pompey to Egypt, arriving soon after the murder of the general. There, Caesar was presented with Pompey's severed head and seal-ring, receiving these with tears.[103] He then had Pompey's assassins put to death.[104]

Caesar then became involved with an Egyptian civil war between the child pharaoh and his sister, wife, and co-regent queen, Cleopatra. Perhaps as a result of the pharaoh's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra. He withstood the Siege of Alexandria and later he defeated the pharaoh's forces at the Battle of the Nile in 47 BC, installing Cleopatra as ruler. Caesar and Cleopatra celebrated their victory with a triumphal procession on the Nile in the spring of 47 BC. The royal barge was accompanied by 400 additional ships, and Caesar was introduced to the luxurious lifestyle of the Egyptian pharaohs.[105]

Caesar and Cleopatra were not married. Caesar continued his relationship with Cleopatra throughout his last marriage – in Roman eyes, this did not constitute adultery – and probably fathered a son called Caesarion. Cleopatra visited Rome on more than one occasion, residing in Caesar's villa just outside Rome across the Tiber.[105]

Late in 48 BC, Caesar was again appointed dictator, with a term of one year.[102] After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, Caesar went to the Middle East, where he annihilated the king of Pontus; his victory was so swift and complete that he mocked Pompey's previous victories over such poor enemies.[106] On his way to Pontus, Caesar visited Tarsus from 27 to 29 May 47 BC, where he met enthusiastic support, but where, according to Cicero, Cassius was planning to kill him at this point.[107][108][109] Thence, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey's senatorial supporters. He was defeated by Titus Labienus at Ruspina on 4 January 46 BC but recovered to gain a significant victory at Thapsus on 6 April 46 BC over Cato, who then committed suicide.[110]

After this victory, he was appointed dictator for 10 years.[111] Pompey's sons escaped to Hispania; Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Battle of Munda in March 45 BC.[112] During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC and 45 BC (this last time without a colleague).

Dictatorship and assassination

While he was still campaigning in Hispania, the Senate began bestowing honours on Caesar. Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoning almost all, and there was no serious public opposition to him. Great games and celebrations were held in April to honour Caesar's victory at Munda. Plutarch writes that many Romans found the triumph held following Caesar's victory to be in poor taste, as those defeated in the civil war had not been foreigners, but instead fellow Romans.[113] On Caesar's return to Italy in September 45 BC, he filed his will, naming his grandnephew Gaius Octavius (Octavian, later known as Augustus Caesar) as his principal heir, leaving his vast estate and property including his name. Caesar also wrote that if Octavian died before Caesar did, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus would be the next heir in succession.[114] In his will, he also left a substantial gift to the citizens of Rome.

Between his crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC, and his assassination in 44 BC, Caesar established a new constitution, which was intended to accomplish three separate goals.[115] First, he wanted to suppress all armed resistance out in the provinces, and thus bring order back to the Republic. Second, he wanted to create a strong central government in Rome. Finally, he wanted to knit together all of the provinces into a single cohesive unit.[115]

The first goal was accomplished when Caesar defeated Pompey and his supporters.[115] To accomplish the other two goals, he needed to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed,[116] so he assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome's other political institutions. Finally, he enacted a series of reforms that were meant to address several long-neglected issues, the most important of which was his reform of the calendar.[117]

Dictatorship

When Caesar returned to Rome, the Senate granted him triumphs for his victories, ostensibly those over Gaul, Egypt, Pharnaces, and Juba, rather than over his Roman opponents. When Arsinoe IV, Egypt's former queen, was paraded in chains, the spectators admired her dignified bearing and were moved to pity.[118] Triumphal games were held, with beast-hunts involving 400 lions, and gladiator contests. A naval battle was held on a flooded basin at the Field of Mars.[119] At the Circus Maximus, two armies of war captives, — each of 2,000 people, 200 horses, and 20 elephants — fought to the death. Again, some bystanders complained, this time at Caesar's wasteful extravagance. A riot broke out, and stopped only when Caesar had two rioters sacrificed by the priests on the Field of Mars.[119]

After the triumph, Caesar set out to pass an ambitious legislative agenda.[119] He ordered a census be taken, which forced a reduction in the grain dole, and decreed that jurors could come only from the Senate or the equestrian ranks. He passed a sumptuary law that restricted the purchase of certain luxuries. After this, he passed a law that rewarded families for having many children, to speed up the repopulation of Italy. Then, he outlawed professional guilds, except those of ancient foundation, since many of these were subversive political clubs. He then passed a term-limit law applicable to governors. He passed a debt-restructuring law, which ultimately eliminated about a fourth of all debts owed.[119]

The Forum of Caesar, with its Temple of Venus Genetrix, was then built, among many other public works.[120] Caesar also tightly regulated the purchase of state-subsidised grain and reduced the number of recipients to a fixed number, all of whom were entered into a special register.[121] From 47 to 44 BC, he made plans for the distribution of land to about 15,000 of his veterans.[122]

The most important change, however, was his reform of the Roman calendar. The calendar at the time was regulated by the movement of the moon. By replacing it with the Egyptian calendar, based on the sun, Roman farmers were able to use it as the basis of consistent seasonal planting from year to year. He set the length of the year to 365.25 days by adding an intercalary/leap day at the end of February every fourth year.[117]

To bring the calendar into alignment with the seasons, he decreed that three extra months be inserted into 46 BC (the ordinary intercalary month at the end of February, and two extra months after November). Thus, the Julian calendar opened on 1 January 45 BC.[117][119] This calendar is almost identical to the current Western calendar.

Shortly before his assassination, he passed a few more reforms.[119] He appointed officials to carry out his land reforms and ordered the rebuilding of Carthage and Corinth. He also extended Latin rights throughout the Roman world, and then abolished the tax system and reverted to the earlier version that allowed cities to collect tribute however they wanted, rather than needing Roman intermediaries. His assassination prevented further and larger schemes, which included the construction of an unprecedented temple to Mars, a huge theatre, and a library on the scale of the Library of Alexandria.[119]

He also wanted to convert Ostia to a major port, and cut a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth. Militarily, he wanted to conquer the Dacians and Parthians, and avenge the loss at Carrhae. Thus, he instituted a massive mobilisation. Shortly before his assassination, the Senate named him censor for life and Pater Patriae (Father of the Country), and the month of Quintilis was renamed July in his honour.[119]

He was granted further honours, which were later used to justify his assassination as a would-be divine monarch: coins were issued bearing his image and his statue was placed next to those of the kings. He was granted a golden chair in the Senate, was allowed to wear triumphal dress whenever he chose, and was offered a form of semi-official or popular cult, with Antony as his high priest.[119]

Political reforms

The history of Caesar's political appointments is complex and uncertain. Caesar held both the dictatorship and the tribunate, but alternated between the consulship and the proconsulship.[116] His powers within the state seem to have rested upon these magistracies.[116] He was first appointed dictator in 49 BC, possibly to preside over elections, but resigned his dictatorship within 11 days. In 48 BC, he was reappointed dictator, only this time for an indefinite period, and in 46 BC, he was appointed dictator for 10 years.[123]

In 48 BC, Caesar was given permanent tribunician powers,[124] which made his person sacrosanct and allowed him to veto the Senate,[124] although on at least one occasion, tribunes did attempt to obstruct him. The offending tribunes in this case were brought before the Senate and divested of their office.[124] This was not the first time Caesar had violated a tribune's sacrosanctity. After he had first marched on Rome in 49 BC, he forcibly opened the treasury, although a tribune had the seal placed on it. After the impeachment of the two obstructive tribunes, Caesar, perhaps unsurprisingly, faced no further opposition from other members of the Tribunician College.[124]

When Caesar returned to Rome in 47 BC, the ranks of the Senate had been severely depleted, so he used his censorial powers to appoint many new senators, which eventually raised the Senate's membership to 900.[125] All the appointments were of his own partisans, which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made the Senate increasingly subservient to him.[126] To minimise the risk that another general might attempt to challenge him,[123] Caesar passed a law that subjected governors to term limits.[123]

In 46 BC, Caesar gave himself the title of "Prefect of the Morals", which was an office that was new only in name, as its powers were identical to those of the censors.[124] Thus, he could hold censorial powers, while technically not subjecting himself to the same checks to which the ordinary censors were subject, and he used these powers to fill the Senate with his own partisans. He also set the precedent, which his imperial successors followed, of requiring the Senate to bestow various titles and honours upon him. He was, for example, given the title of Pater Patriae and imperator.[123]

Coins bore his likeness, and he was given the right to speak first during Senate meetings.[123] Caesar then increased the number of magistrates who were elected each year, which created a large pool of experienced magistrates and allowed Caesar to reward his supporters.[125]

Caesar even took steps to transform Italy into a Roman province and to link more tightly the other provinces of the empire into a single cohesive unit. This process, of fusing the entire Roman Empire into a single unit, rather than maintaining it as a network of unequal principalities, would ultimately be completed by Caesar's successor, the Emperor Augustus.

In October 45 BC, Caesar resigned his position as sole consul, and facilitated the election of two successors for the remainder of the year, which theoretically restored the ordinary consulship, since the constitution did not recognize a single consul without a colleague.[125] In February 44 BC, one month before his assassination, he was appointed dictator in perpetuity. Under Caesar, a significant amount of authority was vested in his lieutenants,[123] mostly because Caesar was frequently out of Italy.[123]

Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire. Since his absence from Rome might limit his ability to install his own consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates, and all consuls and tribunes.[125] This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people to being representatives of the dictator.[125]

Assassination

On the Ides of March (15 March; see Roman calendar) of 44 BC, Caesar was due to appear at a session of the Senate. Several senators had conspired to assassinate Caesar. Mark Antony, having vaguely learned of the plot the night before from a terrified liberator named Servilius Casca, and fearing the worst, went to head Caesar off. The plotters, however, had anticipated this and, fearing that Antony would come to Caesar's aid, had arranged for Trebonius to intercept him just as he approached the portico of the Theatre of Pompey, where the session was to be held, and detain him outside (Plutarch, however, assigns this action of delaying Antony to Brutus Albinus). When he heard the commotion from the Senate chamber, Antony fled.[127]

According to Plutarch, as Caesar arrived at the Senate, Tillius Cimber presented him with a petition to recall his exiled brother.[128] The other conspirators crowded round to offer support. Both Plutarch and Suetonius say that Caesar waved him away, but Cimber grabbed his shoulders and pulled down Caesar's toga. Caesar then cried to Cimber, "Why, this is violence!" ("Ista quidem vis est!").[129]

Casca simultaneously produced his dagger and made a glancing thrust at the dictator's neck. Caesar turned around quickly and caught Casca by the arm. According to Plutarch, he said in Latin, "Casca, you villain, what are you doing?"[130] Casca, frightened, shouted, "Help, brother!" in Greek ("ἀδελφέ, βοήθει", "adelphe, boethei"). Within moments, the entire group, including Brutus, was striking out at the dictator. Caesar attempted to get away, but, blinded by blood, he tripped and fell; the men continued stabbing him as he lay defenceless on the lower steps of the portico. According to Eutropius, around 60 men participated in the assassination. He was stabbed 23 times.[131]

According to Suetonius, a physician later established that only one wound, the second one to his chest, had been lethal.[132] The dictator's last words are not known with certainty, and are a contested subject among scholars and historians alike. Suetonius reports that others have said Caesar's last words were the Greek phrase "καὶ σύ, τέκνον;"[133] (transliterated as "Kai sy, teknon?": "You too, child?" in English). However, Suetonius' own opinion was that Caesar said nothing.[134]

Plutarch also reports that Caesar said nothing, pulling his toga over his head when he saw Brutus among the conspirators.[135] The version best known in the English-speaking world is the Latin phrase "Et tu, Brute?" ("And you, Brutus?", commonly rendered as "You too, Brutus?");[136][137] best known from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, where it actually forms the first half of a macaronic line: "Et tu, Brute? Then fall, Caesar." This version was already popular when the play was written, as it appears in Richard Edes's Latin play Caesar Interfectus of 1582 and The True Tragedie of Richarde Duke of Yorke & etc. of 1595, Shakespeare's source work for other plays.[138]

According to Plutarch, after the assassination, Brutus stepped forward as if to say something to his fellow senators; they, however, fled the building.[139] Brutus and his companions then marched to the Capitol while crying out to their beloved city: "People of Rome, we are once again free!" They were met with silence, as the citizens of Rome had locked themselves inside their houses as soon as the rumour of what had taken place had begun to spread. Caesar's dead body lay where it fell on the Senate floor for nearly three hours before other officials arrived to remove it.

Caesar's body was cremated. A crowd that had gathered at the cremation started a fire, which badly damaged the forum and neighbouring buildings. On the site of his cremation, the Temple of Caesar was erected a few years later (at the east side of the main square of the Roman Forum). Only its altar now remains.[140] A life-size wax statue of Caesar was later erected in the forum displaying the 23 stab wounds.

In the chaos following the death of Caesar, Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), and others fought a series of five civil wars, which would culminate in the formation of the Roman Empire.

Aftermath of the assassination

The result, unforeseen by the assassins, was that Caesar's death precipitated the end of the Roman Republic.[141] The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular and had been since before Gaul, became enraged that a small group of aristocrats had killed their champion. Antony, who had been drifting apart from Caesar, capitalised on the grief of the Roman mob and threatened to unleash them on the Optimates, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself. To his surprise and chagrin, Caesar had named his grandnephew Gaius Octavius his sole heir, bequeathing him the immensely potent Caesar name and making him one of the wealthiest citizens in the Republic.[142]

The crowd at the funeral boiled over, throwing dry branches, furniture, and even clothing on to Caesar's funeral pyre, causing the flames to spin out of control, seriously damaging the Forum. The mob then attacked the houses of Brutus and Cassius, where they were repelled only with considerable difficulty, ultimately providing the spark for the civil war, fulfilling at least in part Antony's threat against the aristocrats.[143] Antony did not foresee the ultimate outcome of the next series of civil wars, particularly with regard to Caesar's adopted heir. Octavian, aged only 18 when Caesar died, proved to have considerable political skills, and while Antony dealt with Decimus Brutus in the first round of the new civil wars, Octavian consolidated his tenuous position.

To combat Brutus and Cassius, who were massing an enormous army in Greece, Antony needed soldiers, the cash from Caesar's war chests, and the legitimacy that Caesar's name would provide for any action he took against them. With the passage of the lex Titia on 27 November 43 BC,[144] the Second Triumvirate was officially formed, composed of Antony, Octavian, and Caesar's loyal cavalry commander Lepidus.[145] It formally deified Caesar as Divus Iulius in 42 BC, and Caesar Octavian henceforth became Divi filius ("Son of the divine").[146]

Because Caesar's clemency had resulted in his murder, the Second Triumvirate reinstated the practice of proscription.[147] It engaged in the legally sanctioned killing of a large number of its opponents to secure funding for its 45 legions in the second civil war against Brutus and Cassius.[148] Antony and Octavian defeated them at Philippi.[149]

Afterward, Antony formed an alliance with Caesar's lover, Cleopatra, intending to use the fabulously wealthy Egypt as a base to dominate Rome. A third civil war broke out between Octavian on one hand and Antony and Cleopatra on the other. This final civil war, culminating in the latter's defeat at Actium in 31 BC and suicide in Egypt in 30 BC, resulted in the permanent ascendancy of Octavian, who became the first Roman emperor, under the name Caesar Augustus, a name conveying religious, rather than political, authority.[150]

Julius Caesar had been preparing to invade Parthia and Scythia, and then march back to Germania through Eastern Europe. These plans were thwarted by his assassination.[151] His successors did attempt the conquests of Parthia and Germania, but without lasting results.

Deification

Julius Caesar was the first historical Roman to be officially deified. He was posthumously granted the title Divus Iulius (the divine/deified Julius) by decree of the Roman Senate on 1 January 42 BC. The appearance of a comet during games in his honour was taken as confirmation of his divinity. Though his temple was not dedicated until after his death, he may have received divine honours during his lifetime:[152] and shortly before his assassination, Antony had been appointed as his flamen (priest).[153] Both Octavian and Antony promoted the cult of Divus Iulius. After the death of Caesar, Octavian, as the adoptive son of Caesar, assumed the title of Divi filius (Son of the Divine).

Personal life

Health and physical appearance

.jpg.webp)

Based on remarks by Plutarch,[154] Caesar is sometimes thought to have suffered from epilepsy. Modern scholarship is sharply divided on the subject, and some scholars believe that he was plagued by malaria, particularly during the Sullan proscriptions of the 80s BC.[155] Other scholars contend his epileptic seizures were due to a parasitic infection in the brain by a tapeworm.[156][157]

Caesar had four documented episodes of what may have been complex partial seizures. He may additionally have had absence seizures in his youth. The earliest accounts of these seizures were made by the biographer Suetonius, who was born after Caesar died. The claim of epilepsy is countered among some medical historians by a claim of hypoglycemia, which can cause epileptoid seizures.[158][159][160]

In 2003, psychiatrist Harbour F. Hodder published what he termed as the "Caesar Complex" theory, arguing that Caesar was a sufferer of temporal lobe epilepsy and the debilitating symptoms of the condition were a factor in Caesar's conscious decision to forgo personal safety in the days leading up to his assassination.[161]

A line from Shakespeare has sometimes been taken to mean that he was deaf in one ear: "Come on my right hand, for this ear is deaf".[162] No classical source mentions hearing impairment in connection with Caesar. The playwright may have been making metaphorical use of a passage in Plutarch that does not refer to deafness at all, but rather to a gesture Alexander of Macedon customarily made. By covering his ear, Alexander indicated that he had turned his attention from an accusation in order to hear the defence.[163]

Francesco M. Galassi and Hutan Ashrafian suggest that Caesar's behavioral manifestations—headaches, vertigo, falls (possibly caused by muscle weakness due to nerve damage), sensory deficit, giddiness and insensibility—and syncopal episodes were the results of cerebrovascular episodes, not epilepsy. Pliny the Elder reports in his Natural History that Caesar's father and forefather died without apparent cause while putting on their shoes. These events can be more readily associated with cardiovascular complications from a stroke episode or lethal heart attack. Caesar possibly had a genetic predisposition for cardiovascular disease.[164]

Suetonius, writing more than a century after Caesar's death, describes Caesar as "tall of stature with a fair complexion, shapely limbs, a somewhat full face, and keen black eyes".[165]

The name Gaius Julius Caesar

Using the Latin alphabet of the period, which lacked the letters J and U, Caesar's name would be rendered GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR; the form CAIVS is also attested, using the older Roman representation of G by C. The standard abbreviation was C. IVLIVS CÆSAR, reflecting the older spelling. (The letterform Æ is a ligature of the letters A and E, and is often used in Latin inscriptions to save space.)

In Classical Latin, it was pronounced [ˈɡaː.i.ʊs ˈjuːl.i.ʊs ˈkae̯sar]. In the days of the late Roman Republic, many historical writings were done in Greek, a language most educated Romans studied. Young wealthy Roman boys were often taught by Greek slaves and sometimes sent to Athens for advanced training, as was Caesar's principal assassin, Brutus. In Greek, during Caesar's time, his family name was written Καίσαρ (Kaísar), reflecting its contemporary pronunciation. Thus, his name is pronounced in a similar way to the pronunciation of the German Kaiser ([kaɪ̯zɐ]) or Dutch keizer ([kɛizɛr]).

In Vulgar Latin, the original diphthong [ae̯] first began to be pronounced as a simple long vowel [ɛː]. Then, the plosive /k/ before front vowels began, due to palatalization, to be pronounced as an affricate, hence renderings like [ˈtʃeːsar] in Italian and [ˈtseːzar] in German regional pronunciations of Latin, as well as the title of Tsar. With the evolution of the Romance languages, the affricate [ts] became a fricative [s] (thus, [ˈseːsar]) in many regional pronunciations, including the French one, from which the modern English pronunciation is derived.

Caesar's cognomen itself became a title; it was promulgated by the Bible, which contains the famous verse "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's". The title became, from the late first millennium, Kaiser in German and (through Old Church Slavic cěsarĭ) Tsar or Czar in the Slavic languages. The last Tsar in nominal power was Simeon II of Bulgaria, whose reign ended in 1946. This means that for approximately two thousand years, there was at least one head of state bearing his name. As a term for the highest ruler, the word Caesar constitutes one of the earliest, best attested and most widespread Latin loanwords in the Germanic languages, being found in the text corpora of Old High German (keisar), Old Saxon (kēsur), Old English (cāsere), Old Norse (keisari), Old Dutch (keisere) and (through Greek) Gothic (kaisar).[166]

Posterity

- Wives

- First marriage to Cornelia (Cinnilla), from 84 BC until her death in 69 or 68 BC

- Second marriage to Pompeia, from 67 BC until he divorced her around 61 BC over the Bona Dea scandal

- Third marriage to Calpurnia, from 59 BC until Caesar's death

- Children

- Julia, by Cornelia, born in 83 or 82 BC

- Caesarion, by Cleopatra VII, born 47 BC, and killed at age 17 by Caesar's adopted son Octavianus.

- Posthumously adopted: Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, his great-nephew by blood (grandson of Julia, his sister), who later became Emperor Augustus.

Suspected Children

- Marcus Junius Brutus (born 85 BC): The historian Plutarch notes that Caesar believed Brutus to have been his illegitimate son, as his mother Servilia had been Caesar's lover during their youth.[168] Caesar would have been 15 years old when Brutus was born.

- Junia Tertia (born ca. 60s BC), the daughter of Caesar's lover Servilia was believed by Cicero among other contemporaries, to be Caesar's natural daughter.

- Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus (born ca. 85–81 BC): On several occasions Caesar expressed how he loved Decimus Brutus like a son. This Brutus was also named an heir of Caesar in case Octavius had died before the latter. Ronald Syme argued that if a Brutus was the natural son of Caesar, Decimus was more likely than Marcus.[169]

- Grandchildren

Grandchild from Julia and Pompey, dead at several days, unnamed.[170]

- Lovers

- Cleopatra, mother of Caesarion

- Servilia, mother of Brutus

- Eunoë, queen of Mauretania and wife of Bogudes

Rumors of passive homosexuality

Roman society viewed the passive role during sexual activity, regardless of gender, to be a sign of submission or inferiority. Indeed, Suetonius says that in Caesar's Gallic triumph, his soldiers sang that, "Caesar may have conquered the Gauls, but Nicomedes conquered Caesar."[171] According to Cicero, Bibulus, Gaius Memmius, and others (mainly Caesar's enemies), he had an affair with Nicomedes IV of Bithynia early in his career. The stories were repeated, referring to Caesar as the "Queen of Bithynia", by some Roman politicians as a way to humiliate him. Caesar himself denied the accusations repeatedly throughout his lifetime, and according to Cassius Dio, even under oath on one occasion.[172] This form of slander was popular during this time in the Roman Republic to demean and discredit political opponents.

Catullus wrote two poems suggesting that Caesar and his engineer Mamurra were lovers,[173] but later apologised.[174]

Mark Antony charged that Octavian had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favors. Suetonius described Antony's accusation of an affair with Octavian as political slander. Octavian eventually became the first Roman Emperor as Augustus.[175]

Literary works

During his lifetime, Caesar was regarded as one of the best orators and prose authors in Latin—even Cicero spoke highly of Caesar's rhetoric and style.[176] Only Caesar's war commentaries have survived. A few sentences from other works are quoted by other authors. Among his lost works are his funeral oration for his paternal aunt Julia and his "Anticato", a document written to defame Cato in response to Cicero's published praise. Poems by Julius Caesar are also mentioned in ancient sources.[177]

Memoirs

- The Commentarii de Bello Gallico, usually known in English as The Gallic Wars, seven books each covering one year of his campaigns in Gaul and southern Britain in the 50s BC, with the eighth book written by Aulus Hirtius on the last two years.

- The Commentarii de Bello Civili (The Civil War), events of the Civil War from Caesar's perspective, until immediately after Pompey's death in Egypt.

Other works historically have been attributed to Caesar, but their authorship is in doubt:

- De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), campaign in Alexandria;

- De Bello Africo (On the African War), campaigns in North Africa; and

- De Bello Hispaniensi (On the Hispanic War), campaigns in the Iberian Peninsula.

These narratives were written and published annually during or just after the actual campaigns, as a sort of "dispatches from the front". They were important in shaping Caesar's public image and enhancing his reputation when he was away from Rome for long periods. They may have been presented as public readings.[178] As a model of clear and direct Latin style, The Gallic Wars traditionally has been studied by first- or second-year Latin students.

Legacy

Historiography

The texts written by Caesar, an autobiography of the most important events of his public life, are the most complete primary source for the reconstruction of his biography. However, Caesar wrote those texts with his political career in mind.[179] Julius Caesar is also considered one of the first historical figures to fold his message scrolls into a concertina form, which made them easier to read. [180] The Roman emperor Augustus began a cult of personality of Caesar, which described Augustus as Caesar's political heir. The modern historiography is influenced by the Octavian traditions, such as when Caesar's epoch is considered a turning point in the history of the Roman Empire. Still, historians try to filter the Octavian bias.[181]

Many rulers in history became interested in the historiography of Caesar. Napoleon III wrote the scholarly work Histoire de Jules César, which was not finished. The second volume listed previous rulers interested in the topic. Charles VIII ordered a monk to prepare a translation of the Gallic Wars in 1480. Charles V ordered a topographic study in France, to place The Gallic Wars in context; which created forty high-quality maps of the conflict. The contemporary Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent catalogued the surviving editions of the Commentaries, and translated them to Turkish language. Henry IV and Louis XIII of France translated the first two commentaries and the last two respectively; Louis XIV retranslated the first one afterwards.[182]

Politics

Julius Caesar is seen as the main example of Caesarism, a form of political rule led by a charismatic strongman whose rule is based upon a cult of personality, whose rationale is the need to rule by force, establishing a violent social order, and being a regime involving prominence of the military in the government.[183] Other people in history, such as the French Napoleon Bonaparte and the Italian Benito Mussolini, have defined themselves as Caesarists.[184][185] Bonaparte did not focus only on Caesar's military career but also on his relation with the masses, a predecessor to populism.[186] The word is also used in a pejorative manner by critics of this type of political rule.

Depictions

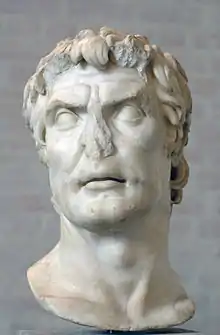

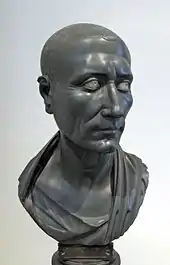

Bust in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples

Bust in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples Modern bronze statue of Julius Caesar, Rimini, Italy

Modern bronze statue of Julius Caesar, Rimini, Italy_at_the_Archaeological_Museum_of_Sparta_on_15_May_2019.jpg.webp) Portrait at the Archaeological Museum of Sparta

Portrait at the Archaeological Museum of Sparta Bronze statue at the Porta Palatina in Turin

Bronze statue at the Porta Palatina in Turin_at_the_Archaeological_Museum_of_Corinth_on_10_January_2020.jpg.webp) Bust in the Archaeological Museum of Corinth

Bust in the Archaeological Museum of Corinth.JPG.webp) Bust in Naples National Archaeological Museum, photograph published in 1902

Bust in Naples National Archaeological Museum, photograph published in 1902

Battle record

| Date | War | Action | Opponent/s | Type | Country (present day) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of the Arar | Helvetii | Battle | France | Victory

|

| 58 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of Bibracte | Helvetii, Boii, Tulingi, Rauraci | Battle | France | Victory

|

| 58 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of Vosges | Suebi | Battle | France | Victory

|

| 57 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of the Axona | Belgae | Battle | France | Victory

|

| 57 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of the Sabis | Nervii, Viromandui,

Atrebates, Aduatuci |

Battle | France | Victory

|

| 55 and 54 BC | Gallic Wars | Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain | Celtic Britons | Campaign | England | Victory

|

| 54 BC–53 BC | Gallic Wars | Ambiorix's revolt | Eburones | Campaign | Belgium, France | Victory

|

| 52 BC | Gallic Wars | Avaricum | Bituriges, Arverni | Siege | France | Victory

|

| 52 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of Gergovia | Gallic tribes | Battle | France | Defeat |

| September 52 BC | Gallic Wars | Battle of Alesia | Gallic Confederation | Siege and Battle | Alise-Sainte-Reine, France | Decisive Victory

|

| 51 BC | Gallic Wars | Siege of Uxellodunum | Gallic | Siege | Vayrac, France | Victory

|

| June–August 49 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Ilerda | Optimates | Battle | Catalonia, Spain | Victory

|

| 10 July 48 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Dyrrhachium (48 BC) | Optimates | Battle | Durrës, Albania | Defeat

|

| 9 August 48 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Pharsalus | Pompeians | Battle | Greece | Decisive Victory

|

| 47 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of the Nile | Ptolemaic Kingdom | Battle | Alexandria, Egypt | Victory

|

| 2 August 47 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Zela | Kingdom of Pontus | Battle | Zile, Turkey | Victory

|

| 4 January 46 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Ruspina | Optimates, Numidia | Battle | Ruspina Africa | Defeat

|

| 6 April 46 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Thapsus | Optimates, Numidia | Battle | Tunisia | Decisive Victory

|

| 17 March 45 BC | Caesar's Civil War | Battle of Munda | Pompeians | Battle | Andalusia Spain | Victory

|

Chronology

See also

- Et tu, Brute?

- Julius Caesar, a play by William Shakespeare (c. 1599)

- Giulio Cesare, an opera by Handel, 1724

- Veni, vidi, vici

- Caesareum of Alexandria

- Caesar cipher

References

- For 13 July being the wrong date, see Badian in Griffin (ed.) p.16 Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Keppie, Lawrence (1998). "The approach of civil war". The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8061-3014-9.

- Suetonius (121). "De vita Caesarum" [The Twelve Caesars]. University of Chicago. p. 107. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012.

More than sixty joined the conspiracy against [Caesar], led by Gaius Cassius and Marcus and Decimus Brutus.

- Plutarch. "Life of Caesar". University of Chicago. p. 595. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

... at this juncture Decimus Brutus, surnamed Albinus, who was so trusted by Caesar that he was entered in his will as his second heir, but was partner in the conspiracy of the other Brutus and Cassius, fearing that if Caesar should elude that day, their undertaking would become known, ridiculed the seers and chided Caesar for laying himself open to malicious charges on the part of the senators ...

- Tucker, Spencer (2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 68. ISBN 9781598844306.

- Froude, James Anthony (1879). Life of Caesar. Project Gutenberg e-text. p. 67. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. See also: Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Julius 6 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.41 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Virgil, Aeneid

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:28–30

- Dionysius, iii. 29.

- Tacitus, Annales, xi. 24.

- Niebuhr, vol. i. note 1240, vol. ii. note 421.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.7 Archived 20 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. The misconception that Julius Caesar himself was born by Caesarian section dates back at least to the 10th century (Suda kappa 1199 Archived 17 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine). Julius was not the first to bear the name, and in his time the procedure was only performed on dead women, while Caesar's mother Aurelia lived long after he was born.

- Historia Augusta: Aelius 2 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Goldsworthy, p. 32 Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Suetonius, Julius 1 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 1 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Marius 6 Archived 13 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.54 Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Inscriptiones Italiae, 13.3.51–52

- Plutarch, Marius 6 Archived 13 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Plutarch, Caesar 1 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Suetonius, Julius 1 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Suetonius, Julius 1 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.54 Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.22 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Florus, Epitome of Roman History 2.9

- "Julius Caesar". Archived from the original on 22 March 2012.

- Suetonius, Julius 1 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 1 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.41 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Canfora, p. 3

- William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: Flamen Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 2–3 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 2–3 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.20 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 46 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- "Suetonius • Life of Julius Caesar". Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Again, according to Suetonius's chronology (Julius 4 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today). Plutarch (Caesar 1.8–2 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives) says this happened earlier, on his return from Nicomedes's court. Velleius Paterculus (Roman History 2:41.3–42 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine) says merely that it happened when he was a young man.

- Plutarch, Caesar 1–2

- "Plutarch • Life of Caesar". penelope.uchicago.edu. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- Thorne, James (2003). Julius Caesar: Conqueror and Dictator. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 15.

- Freeman, 39

- Freeman, 40

- Goldsworthy, 77–78

- Freeman, 51

- Freeman, 52

- Goldsworthy, 100

- Goldsworthy, 101

- Suetonius, Julius 5–8 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 5 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Mouritsen, Henrik, Plebs and Politics in the Late Roman Republic, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p 97. ISBN 0-521-79100-6 For context, see Plutarch, Julius Caesar, 5.4.

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Plutarch, Caesar 7 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Suetonius, Julius 13 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Sallust, Catiline War 49 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Kennedy, E.C. (1958). Caesar de Bello Gallico. Cambridge Elementary Classics. Vol. III. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 10. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Hammond, Mason (1966). City-state and World State in Greek and Roman Political Theory Until Augustus. Biblo & Tannen. p. 114. ISBN 9780819601766. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Suetonius (2004). Lives of the Caesars. Barnes and Noble Library of Essential Reading Series. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Barnes & Noble. p. 258. ISBN 9780760757581. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (American Philological Association, 1952), vol. 2, pp. 180 and 173.

- Colegrove, Michael (2007). Distant Voices: Listening to the Leadership Lessons of the Past. iUniverse. p. 9. ISBN 9780595472062. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Plutarch, Caesar 11–12 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Suetonius, Julius 18.1 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Plutarch, Julius 13 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Suetonius, Julius 18.2 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Plutarch, Caesar 13–14 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives; Suetonius 19 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.1, 2.3, 2.17; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.44 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Plutarch, Caesar 13–14 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Pompey 47 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Crassus 14 Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine; Suetonius, Julius 19.2 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.54–58 Archived 20 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 21 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.15, 2.16, 2.17, 2.18, 2.19, 2.20, 2.21; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 44.4 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Plutarch, Caesar 14 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Pompey 47–48 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Cato the Younger 32–33 Archived 10 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Cassius Dio, Roman History 38.1–8 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 19.2 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- von Ungern-Sternberg, Jurgen (2014). "The Crisis of the Republic". In Flower, Harriet (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 91. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521807948. ISBN 9781139000338.

- Bucher, Gregory S (2011). "Caesar: the view from Rome". The Classical Outlook. 88 (3): 82–87. ISSN 0009-8361. JSTOR 43940076.

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2:44.4 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Plutarch, Caesar 14.10 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Crassus 14.3 Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Pompey 48 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Cato the Younger 33.3 Archived 10 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Suetonius, Julius 22 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Cassius Dio, Roman History 38:8.5 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 23 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- See Cicero's speeches against Verres for an example of a former provincial governor successfully prosecuted for illegally enriching himself at his province's expense.

- Cicero, Letters to Atticus 1.19; Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 1; Appian, Gallic Wars Epit. 3 Archived 18 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine; Cassius Dio, Roman History 38.31–50 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 2; Appian, Gallic Wars Epit. 4 Archived 18 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine; Cassius Dio, Roman History 39.1–5 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Cicero, Letters to his brother Quintus 2.3 Archived 20 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine; Suetonius, Julius 24 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 21 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Crassus 14–15 Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Pompey 51 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 3; Cassius Dio, Roman History 39.40–46 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Black, Jeremy (2003). A History of the British Isles. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 6.

- Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 4; Appian, Gallic Wars Epit. 4 Archived 18 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine; Cassius Dio, Roman History 47–53 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Cicero, Letters to friends 7.6, 7.7, 7.8, 7.10, 7.17; Letters to his brother Quintus 2.13, 2.15, 3.1; Letters to Atticus 4.15, 4.17, 4.18; Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 5–6; Cassius Dio, Roman History 40.1–11 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "France: The Roman conquest". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix's Great Rebellion of 52 bce had notable successes.

- "Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

Indeed, the Gallic cavalry was probably superior to the Roman, horseman for horseman. Rome's military superiority lay in its mastery of strategy, tactics, discipline, and military engineering. In Gaul, Rome also had the advantage of being able to deal separately with dozens of relatively small, independent, and uncooperative states. Caesar conquered these piecemeal, and the concerted attempt made by a number of them in 52 bce to shake off the Roman yoke came too late.

- Julius Caesar, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 7; Cassius Dio, Roman History 40.33–42 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Aulus Hirtius, Commentaries on the Gallic War Book 8

- "Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, by Plutarch (chapter48)". Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- Grillo, Luca; Krebs, Christopher B., eds. (2018). The Cambridge companion to the writings of Julius Caesar. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-02341-3. OCLC 1010620484. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Suetonius, Julius Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today; Plutarch, Caesar 23.5 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Pompey 53–55 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Crassus 16–33 Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 46–47 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 248.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 258. See also Appendix 4 in the same book, analysing the conflict between Caesar and Pompey in terms of a Prisoner's dilemma.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 270.

- Drogula, Fred K (2019). Cato the Younger: life and death at the end of the Roman republic. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-19-086902-1. OCLC 1090168108.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 273.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 272, 276, 295 (identities of Cato's allies).

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 291.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 292–93.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 297.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 304.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 306.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 308.

- Ehrhardt, C. T. H. R. (1995). "Crossing the Rubicon". Antichthon. 29: 30–41. doi:10.1017/S0066477400000927. ISSN 0066-4774. S2CID 142429003. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

Everyone knows that Caesar crossed the Rubicon because [he would have been...] put on trial, found guilty and have his political career ended... Yet over thirty years ago, Shackleton Bailey, in less than two pages of his introduction to Cicero's Letters to Atticus, destroyed the basis for this belief, and... no one has been able to rebuild it.

- Morstein-Marx, Robert (2007). "Caesar's Alleged Fear of Prosecution and His "Ratio Absentis" in the Approach to the Civil War". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 56 (2): 159–178. doi:10.25162/historia-2007-0013. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 25598386. S2CID 159090397. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 262–63, explaining:

- Any prosecution was extremely unlikely to succeed.

- No contemporary source expresses dissatisfaction with an inability to prosecute.

- No timely charges could have been brought. The possibility of conviction for irregularities during his consulship in 59 "seems to be nothing more than a pipe dream" when none of Caesar's actions in 59 were overturned. Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 624.

- Caesar proposed giving up his command – opening himself up to prosecution – in January 49 BC as part of peace negotiations, something he would not have proposed if he were worried about a sure-fire conviction.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 288. "Caesar feared that the only guarantee of his rights... to stand for election in absentia under the protection of the Law of the Ten Tribunes and to receive a triumph... was his army".

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 309.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 320.

- Beard, Mary (2016). SPQR: a history of ancient Rome. W.W. Norton. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-8466-8381-7.

the exact date is unknown

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 322.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 331.

- Plutarch, Caesar 32.8 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Thomson, D. F. S.; Sperna Weiland, Jan (1988). "Erasmus and textual scholarship: Suetonius". In Weiland, J. S. (ed.). Erasmus of Rotterdam: the man and the scholar. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill. p. 161. ISBN 978-90-04-08920-4.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 336.

- Morstein-Marx 2021, pp. 340 (Caesar's pause), 342 (Caesar's offer), 343 (Pompey's counter-offer), 345 (negotiations collapse).

- Morstein-Marx 2021, p. 347.

- Plutarch, Caesar 42–45 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Roller, Duane W. (2010). Cleopatra: a biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195365535, p. 175.

- Walker, Susan. "Cleopatra in Pompeii? Archived 10 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine" in Papers of the British School at Rome, 76 (2008): 35–46 and 345–8 (pp. 35, 42–44).

- Plutarch, Caesar 37.2 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Martin Jehne, Der Staat des Dicators Caesar, Köln/Wien 1987, p. 15–38.

- Plutarch, Pompey 80.5 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Plutarch, Pompey 77–79 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Salisbury, Joyce E (2001). "Cleopatra VII". Women in the ancient world. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-57607-092-5.

- Suetonius, Julius 35.2 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Caesar: a history of the art of war among the Romans down to the end of the Roman empire, with a detailed account of the campaigns of Caius Julius Caesar, page 791, Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Greenhill Books, 1995. ISBN 9781853672163

- Paul: The Man and the Myth, page 15, Studies on personalities of the New Testament Personalities of the New Testament Series, Calvin J. Roetzel, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1999. ISBN 9780567086983

- Julius Caesar, page 311, Philip Freeman, Simon and Schuster, 2008. ISBN 9780743289535

- Plutarch, Caesar 52–54 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Martin Jehne, Der Staat des Dictators Caesar, Köln/Wien 1987, p. 15–38. Technically, Caesar was not appointed dictator with a term of 10 years, but he was appointed annual dictator for the next 10 years in advance.

- Plutarch, Caesar 56 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Plutarch, Caesar 56.7–56.8 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Appian, The Civil Wars 2:143.1 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Abbott, 133

- Abbott, 134

- Suetonius, Julius 40 Archived 30 May 2012 at archive.today

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.19.2–3; Appian, Civil Wars 2.101.420

- J.F.C. Fuller, Julius Caesar, Man, Soldier, Tyrant, Chapter 13

- Diana E. E. Kleiner. Julius Caesar, Venus Genetrix, and the Forum Iulium (Multimedia presentation). Yale University. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2004). Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History. Cambridge University Press. p. 254.

- Campbell, J. B. (1994). The Roman Army, 31 BC–AD 337. Routledge. p. 10.

- Abbott, 136

- Abbott, 135

- Abbott, 137

- Abbott, 138

- Huzar, Eleanor Goltz (1978). Mark Antony, a biography By Eleanor Goltz Huzar. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-8166-0863-8.

- "Plutarch—Life of Brutus". Classics.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "Suetonius, 'Life of the Caesars, Julius', trans. J C Rolfe". Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Plutarch, Life of Caesar, ch. 66: "ὁ μεν πληγείς, Ῥωμαιστί· 'Μιαρώτατε Κάσκα, τί ποιεῖς;'"

- Woolf Greg (2006), Et Tu Brute?—The Murder of Caesar and Political Assassination, 199 pages—ISBN 1-86197-741-7

- Suetonius, Julius, c. 82.

- Suetonius, Julius 82.2 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- From the J. C. Rolfe translation of 1914: "...he was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, 'You too, my child?".

- Plutarch, Caesar 66.9 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Stone, Jon R. (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations. London: Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-415-96909-3.

- Morwood, James (1994). The Pocket Oxford Latin Dictionary (Latin-English). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860283-5.

- Dyce, Alexander (1866). The Works of William Shakespeare. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 648.

Quoting Malone

- Plutarch, Caesar 67 Archived 13 February 2018 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- "Temple of Caesar". Anamericaninrome.com. 2 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Florus, Epitome 2.7.1 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Suetonius, Julius 83.2 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "Suetonius, Life of Caesar, Chapters LXXXIII, LXXXIV, LXXXV". Ancienthistory.about.com. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 31 August 2004. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Osgood, Josiah (2006). Caesar's Legacy: Civil War and the Emergence of the Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 60.

- Suetonius, Augustus 13.1 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Florus, Epitome 2.6 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Warrior, Valerie M. (2006). Roman Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-521-82511-5.

- Florus, Epitome 2.6.3 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Zoch, Paul A. (200). Ancient Rome: An Introductory History. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-8061-3287-7.

- Florus, Epitome 2.7.11–14 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine; Appian, The Civil Wars 5.3 Archived 27 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Florus, Epitome 2.34.66 Archived 31 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine