Vitruvius

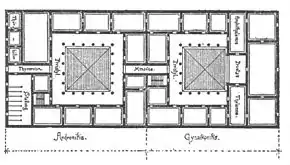

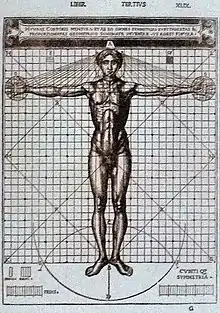

Vitruvius (/vɪˈtruːviəs/; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled De architectura.[1] He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas ("strength", "utility", and "beauty").[2] These principles were later widely adopted in Roman architecture. His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci.

Vitruvius | |

|---|---|

A 1684 depiction of Vitruvius (right) presenting De Architectura to Augustus | |

| Born | 80–70 BC |

| Died | 15 BC (aged 55–65) |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable work | De architectura |

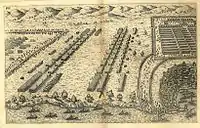

Little is known about Vitruvius' life, but by his own description[3] he served as an artilleryman, the third class of arms in the Roman military offices. He probably served as a senior officer of artillery in charge of doctores ballistarum (artillery experts) and libratores who actually operated the machines.[4] As an army engineer he specialized in the construction of ballista and scorpio artillery war machines for sieges. It is possible that Vitruvius served with Julius Caesar's chief engineer Lucius Cornelius Balbus.

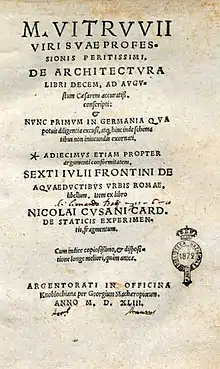

Vitruvius' De architectura was widely copied and survives in many dozens of manuscripts throughout the Middle Ages,[5] though in 1414 it was "rediscovered" by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini in the library of Saint Gall Abbey. Leon Battista Alberti published it in his seminal treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria (c. 1450). The first known Latin printed edition was by Fra Giovanni Sulpitius in Rome in 1486. Translations followed in Italian, French, English, German, Spanish, and several other languages. Though the original illustrations have been lost, the first illustrated edition was published in Venice in 1511 by Fra Giovanni Giocondo, with woodcut illustrations based on descriptions in the text.

Life and career

Little is known about Vitruvius' life. Most inferences about him are extracted from his only surviving work De Architectura. His full name is sometimes given as "Marcus Vitruvius Pollio", but both the first and last names are uncertain.[6] Marcus Cetius Faventinus writes of "Vitruvius Polio aliique auctores"; this can be read as "Vitruvius Polio, and others" or, less likely, as "Vitruvius, Polio, and others". An inscription in Verona, which names a Lucius Vitruvius Cordo, and an inscription from Thilbilis in North Africa, which names a Marcus Vitruvius Mamurra have been suggested as evidence that Vitruvius and Mamurra (who was a military praefectus fabrum under Julius Caesar) were from the same family;[7] or were even the same individual. Neither association, however, is borne out by De Architectura (which Vitruvius dedicated to Augustus), nor by the little that is known of Mamurra.

Vitruvius was a military engineer (praefectus fabrum), or a praefect architectus armamentarius of the apparitor status group (a branch of the Roman civil service). He is mentioned in Pliny the Elder's table of contents for Naturalis Historia (Natural History), in the heading for mosaic techniques.[8] Frontinus refers to "Vitruvius the architect" in his late 1st-century work De aquaeductu.

Likely born a free Roman citizen, by his own account, Vitruvius served in the Roman army under Caesar with the otherwise poorly identified Marcus Aurelius, Publius Minidius, and Gnaeus Cornelius. These names vary depending on the edition of De architectura. Publius Minidius is also written as Publius Numidicus and Publius Numidius, speculated as the same Publius Numisius inscribed on the Roman Theatre at Heraclea.[9]

As an army engineer he specialized in the construction of ballista and scorpio artillery war machines for sieges. It is speculated that Vitruvius served with Caesar's chief engineer Lucius Cornelius Balbus.[10]

The locations where he served can be reconstructed from, for example, descriptions of the building methods of various "foreign tribes". Although he describes places throughout De Architectura, he does not say he was present. His service likely included north Africa, Hispania, Gaul (including Aquitaine) and Pontus.

To place the role of Vitruvius the military engineer in context, a description of "The Prefect of the camp" or army engineer is quoted here as given by Flavius Vegetius Renatus in The Military Institutions of the Romans:

The Prefect of the camp, though inferior in rank to the [Prefect], had a post of no small importance. The position of the camp, the direction of the entrenchments, the inspection of the tents or huts of the soldiers and the baggage were comprehended in his province. His authority extended over the sick, and the physicians who had the care of them; and he regulated the expenses relative thereto. He had the charge of providing carriages, bathhouses and the proper tools for sawing and cutting wood, digging trenches, raising parapets, sinking wells and bringing water into the camp. He likewise had the care of furnishing the troops with wood and straw, as well as the rams, onagri, balistae and all the other engines of war under his direction. This post was always conferred on an officer of great skill, experience and long service, and who consequently was capable of instructing others in those branches of the profession in which he had distinguished himself.[11]

At various locations described by Vitruvius,[12] battles and sieges occurred. He is the only source for the siege of Larignum in 56 BC.[13] Of the battlegrounds of the Gallic War there are references to:

- The siege and massacre of the 40,000 residents at Avaricum in 52 BC. Vercingetorix commented that "the Romans did not conquer by valour nor in the field, but by a kind of art and skill in assault, with which they [Gauls] themselves were unacquainted."[14]

- The broken siege at Gergovia in 52 BC.

- The circumvallation and Battle of Alesia in 52 BC. The women and children of the encircled city were evicted to conserve food, and then starved to death between the opposing walls of the defenders and besiegers.

- The siege of Uxellodunum in 51 BC.

These are all sieges of large Gallic oppida. Of the sites involved in Caesar's civil war, we find the Siege of Massilia in 49 BC,[15] the Battle of Dyrrhachium of 48 BC (modern Albania), the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC (Hellas – Greece), the Battle of Zela of 47 BC (modern Turkey), and the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BC in Caesar's African campaign.[16] A legion that fits the same sequence of locations is the Legio VI Ferrata, of which ballista would be an auxiliary unit.

Mainly known for his writings, Vitruvius was himself an architect. In Roman times architecture was a broader subject than at present including the modern fields of architecture, construction management, construction engineering, chemical engineering, civil engineering, materials engineering, mechanical engineering, military engineering and urban planning;[17] architectural engineers consider him the first of their discipline, a specialization previously known as technical architecture.

In his work describing the construction of military installations, he also commented on the miasma theory – the idea that unhealthy air from wetlands was the cause of illness, saying:

For fortified towns the following general principles are to be observed. First comes the choice of a very healthy site. Such a site will be high, neither misty nor frosty, and in a climate neither hot nor cold, but temperate; further, without marshes in the neighbourhood. For when the morning breezes blow toward the town at sunrise, if they bring with them mists from marshes and, mingled with the mist, the poisonous breath of the creatures of the marshes to be wafted into the bodies of the inhabitants, they will make the site unhealthy. Again, if the town is on the coast with southern or western exposure, it will not be healthy, because in summer the southern sky grows hot at sunrise and is fiery at noon, while a western exposure grows warm after sunrise, is hot at noon, and at evening all aglow.[18]

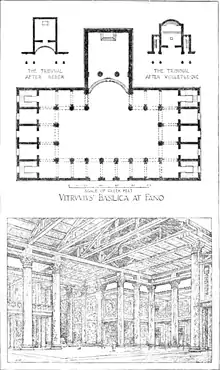

Frontinus mentions Vitruvious in connection with the standard sizes of pipes:[19] the role he is most widely respected. He is often credited as father of architectural acoustics for describing the technique of echeas placement in theaters.[20] The only building, however, that we know Vitruvius to have worked on is one he tells us about,[21] a basilica completed in 19 BC.[22] It was built at Fanum Fortunae, now the modern town of Fano. The Basilica di Fano (to give the building its Italian name) has disappeared so completely that its very site is a matter of conjecture, although various attempts have been made to visualise it.[23] The early Christian practice of converting Roman basilicae (public buildings) into cathedrals implies the basilica may be incorporated into the cathedral in Fano.

In later years the emperor Augustus, through his sister Octavia Minor, sponsored Vitruvius, entitling him with what may have been a pension to guarantee financial independence.[3]

Whether De architectura was written by one author or is a compilation completed by subsequent librarians and copyists, remains an open question. The date of his death is unknown, which suggests that he had enjoyed only a little popularity during his lifetime.

Gerolamo Cardano, in his 1552 book De subtilitate rerum, ranks Vitruvius as one of the 12 persons whom he supposes to have excelled all men in the force of genius and invention; and would not have scrupled to have given him the first place if it could be imagined that he had delivered nothing but his own discoveries.[24]

De architectura

Vitruvius is the author of De architectura, libri decem, known today as The Ten Books on Architecture,[25] a treatise written in Latin on architecture, dedicated to the emperor Augustus. In the preface of Book I, Vitruvius dedicates his writings to giving personal knowledge of the quality of buildings to the emperor. Likely Vitruvius is referring to Marcus Agrippa's campaign of public repairs and improvements. This work is the only surviving major book on architecture from classical antiquity. According to Petri Liukkonen, this text "influenced deeply from the Early Renaissance onwards artists, thinkers, and architects, among them Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), and Michelangelo (1475–1564)."[16] The next major book on architecture, Alberti's reformulation of Ten Books, was not written until 1452.

Vitruvius is famous for asserting in his book De architectura that a structure must exhibit the three qualities of firmitatis, utilitatis, venustatis – that is, stability, utility, and beauty. These are sometimes termed the Vitruvian virtues or the Vitruvian Triad. According to Vitruvius, architecture is an imitation of nature. As birds and bees built their nests, so humans constructed housing from natural materials, that gave them shelter against the elements. When perfecting this art of building, the Greeks invented the architectural orders: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. It gave them a sense of proportion, culminating in understanding the proportions of the greatest work of art: the human body. This led Vitruvius in defining his Vitruvian Man, as drawn later by Leonardo da Vinci: the human body inscribed in the circle and the square (the fundamental geometric patterns of the cosmic order). In this book series, Vitruvius, also wrote about climate in relation to housing architecture and how to choose locations for cities.[26][27]

Scope

Vitruvius is sometimes loosely referred to as the first architect, but it is more accurate to describe him as the first Roman architect to have written surviving records of his field. He himself cites older but less complete works. He was less an original thinker or creative intellect than a codifier of existing architectural practice. Vitruvius had a much wider scope than modern architects. Roman architects practised a wide variety of disciplines; in modern terms, they could be described as being engineers, architects, landscape architects, surveyors, artists, and craftsmen combined. Etymologically the word architect derives from Greek words meaning 'master' and 'builder'. The first of the Ten Books deals with many subjects which now come within the scope of landscape architecture.

In Book I, Chapter 1, titled The Education of the Architect, Vitruvius instructs...

1. Architecture is a science arising out of many other sciences, and adorned with much and varied learning; by the help of which a judgment is formed of those works which are the result of other arts. Practice and theory are its parents. Practice is the frequent and continued contemplation of the mode of executing any given work, or of the mere operation of the hands, for the conversion of the material in the best and readiest way. Theory is the result of that reasoning which demonstrates and explains that the material wrought has been so converted as to answer the end proposed.

2. Wherefore the mere practical architect is not able to assign sufficient reasons for the forms he adopts; and the theoretic architect also fails, grasping the shadow instead of the substance. He who is theoretic as well as practical, is therefore doubly armed; able not only to prove the propriety of his design, but equally so to carry it into execution.[28]

He goes on to say that the architect should be versed in drawing, geometry, optics (lighting), history, philosophy, music, theatre, medicine, and law.

In Book I, Chapter 3 (The Departments of Architecture), Vitruvius divides architecture into three branches, namely; building; the construction of sundials and water clocks;[29] and the design and use of machines in construction and warfare.[30][31] He further divides building into public and private. Public building includes city planning, public security structures such as walls, gates and towers; the convenient placing of public facilities such as theatres, forums and markets, baths, roads and pavings; and the construction and position of shrines and temples for religious use.[28] Later books are devoted to the understanding, design and construction of each of these.

Proportions of man

In Book III, Chapter 1, Paragraph 3, Vitruvius writes about the proportions of man:

3. Just so the parts of Temples should correspond with each other, and with the whole. The navel is naturally placed in the centre of the human body, and, if in a man lying with his face upward, and his hands and feet extended, from his navel as the centre, a circle be described, it will touch his fingers and toes. It is not alone by a circle, that the human body is thus circumscribed, as may be seen by placing it within a square. For measuring from the feet to the crown of the head, and then across the arms fully extended, we find the latter measure equal to the former; so that lines at right angles to each other, enclosing the figure, will form a square.[32]

It was upon these writings that Renaissance engineers, architects and artists like Mariano di Jacopo Taccola, Pellegrino Prisciani and Francesco di Giorgio Martini and finally Leonardo da Vinci based the illustration of the Vitruvian Man.[33]

Vitruvius described the human figure as being the principal source of proportion.

The drawing itself is often used as an implied symbol of the essential symmetry of the human body, and by extension, of the universe as a whole.[34]

Lists of names given in Book VII Introduction

In the introduction to book seven, Vitruvius goes to great lengths to present why he is qualified to write De Architectura. This is the only location in the work where Vitruvius specifically addresses his personal breadth of knowledge. Similar to a modern reference section, the author's position as one who is knowledgeable and educated is established. The topics range across many fields of expertise reflecting that in Roman times as today construction is a diverse field. Vitruvius is clearly a well-read man.

In addition to providing his qualification, Vitruvius summarizes a recurring theme throughout the 10 books, a non-trivial and core contribution of his treatise beyond simply being a construction book. Vitruvius makes the point that the work of some of the most talented is unknown, while many of those of lesser talent but greater political position are famous.[25] This theme runs through Vitruvius's ten books repeatedly – echoing an implicit prediction that he and his works will also be forgotten.

Vitruvius illustrates this point by naming what he considers the most talented individuals in history.[25] Implicitly challenging the reader that they have never heard of some of these people, Vitruvius goes on and predicts that some of these individuals will be forgotten and their works lost, while other, less deserving political characters of history will be forever remembered with pageantry.

- List of physicists: Thales, Democritus, Anaxagoras, Xenophanes

- List of philosophers: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Zeno, Epicurus

- List of kings: Croesus, Alexander the Great, Darius

- On plagiarism: Aristophanes, Ptolemy I Soter, a person named Attalus

- On abusing dead authors: Zoilus Homeromastix, Ptolemy II Philadelphus

- On divergence of the visual rays: Agatharchus, Aeschylus, Democritus, Anaxagoras

- List of writers on temples: Silenus, Theodorus, Chersiphron and Metagenes, Ictinus and Carpion, Theodorus the Phocian, Hermogenes, Arcesius, Satyrus and a person named Pytheos

- List of artists: Leochares, Bryaxis, Scopas, Praxiteles, Timotheos

- List of writers on laws of symmetry: Nexaris, Theocydes, a person named Demophilus, Pollis, a person named Leonidas, Silanion, Melampus, Sarnacus, Euphranor

- List of writers on machinery: Diades of Pella, Archytas, Archimedes, Ctesibius, Nymphodorus, Philo of Byzantium, Diphilus, Democles, Charias, Polyidus of Thessaly, Pyrrus, Agesistratus

- List of writers on architecture: Fuficius, Terentius Varro, Publius Septimius (writer)

- List of architects: Antistates, Callaeschrus, Antimachides, Pormus, Cossutius

- List of greatest temple architects: Chersiphron of Gnosus, Metagenes, Demetrius, Paeonius the Milesian, Ephesian Daphnis, Ictinus, Philo, Cossutius, Gaius Mucianus

Rediscovery

Vitruvius' De architectura was "rediscovered" in 1414 by the Florentine humanist Poggio Bracciolini in the library of Saint Gall Abbey. Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) publicised it in his seminal treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria (c. 1450). The first known Latin printed edition was by Fra Giovanni Sulpitius in Rome, 1486.[35] Translations followed in Italian (Cesare Cesariano, 1521), French (Jean Martin, 1547[36]), English, German (Walther H. Ryff, 1543) and Spanish and several other languages. The original illustrations had been lost and the first illustrated edition was published in Venice in 1511 by Fra Giovanni Giocondo, with woodcut illustrations based on descriptions in the text.[37] Later in the 16th-century Andrea Palladio provided illustrations for Daniele Barbaro's commentary on Vitruvius, published in Italian and Latin versions. The most famous illustration is probably Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man.

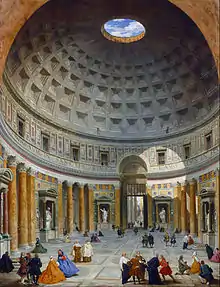

The surviving ruins of Roman antiquity, the Roman Forum, temples, theatres, triumphal arches and their reliefs and statues offered visual examples of the descriptions in the Vitruvian text. Printed and illustrated editions of De Architectura inspired Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical architecture. Filippo Brunelleschi, for example, invented a new type of hoist to lift the large stones for the dome of the cathedral in Florence and was inspired by De Architectura as well as surviving Roman monuments such as the Pantheon and the Baths of Diocletian.

Notable editions

Latin

- 1495–1496 De architectura (in Latin). Venezia: Cristoforo Pensi.

- 1543 De architectura (in Latin). Strasbourg: Georg Messerschmidt.

- 1800 Augustus Rode, Berlin[38]

- 1857 Teubner Edition by Valentin Rose

- 1899 Teubner Edition

- 1912 Teubner edition at The Latin Library[39]

- Bill Thayer, transcription of the 1912 Teubner Edition[40]

Italian

- Cesare Cesariano, 1521, Como, Italy, includes illustrations by Cesare Cesariano

- Danielle Barbaro, includes illustration by Andrea Palladio

French

English

- Henry Wotton, 1624

- Joseph Gwilt, 1826

- Bill Thayer transcription of the Gwilt 1826 Edition[28]

- Morris H. Morgan, with illustrations prepared by Herbert Langford Warren, 1914, Harvard University Press[43]

- Frank Granger, Loeb Edition, 1931[44]

- Ingrid Rowland, 2001[45]

- Thomas Gordon Smith, The Monacelli Press (5 January 2004)[46]

Roman technology

Books VIII, IX and X form the basis of much of what we know about Roman technology, now augmented by archaeological studies of extant remains, such as the water mills at Barbegal in France. The other major source of information is the Naturalis Historia compiled by Pliny the Elder much later in c. 75 AD.

Machines

The work is important for its descriptions of the many different machines used for engineering structures such as hoists, cranes and pulleys, as well as war machines such as catapults, ballistae, and siege engines. As a practising engineer, Vitruvius must be speaking from personal experience rather than simply describing the works of others. He also describes the construction of sundials and water clocks, and the use of an aeolipile (the first steam engine) as an experiment to demonstrate the nature of atmospheric air movements (wind).

Aqueducts

His description of aqueduct construction includes the way they are surveyed, and the careful choice of materials needed, although Frontinus (a general who was appointed in the late 1st century AD to administer the many aqueducts of Rome), writing a century later, gives much more detail of the practical problems involved in their construction and maintenance. Surely Vitruvius' book would have been of great assistance in this. Vitruvius was writing in the 1st century BC when many of the finest Roman aqueducts were built, and survive to this day, such as those at Segovia and the Pont du Gard. The use of the inverted siphon is described in detail, together with the problems of high pressures developed in the pipe at the base of the siphon, a practical problem with which he seems to be acquainted.

Materials

He describes many different construction materials used for a wide variety of different structures, as well as such details as stucco painting. Concrete and lime receive in-depth descriptions.

Vitruvius is cited as one of the earliest sources to connect lead mining and manufacture, its use in drinking water pipes, and its adverse effects on health. For this reason, he recommended the use of clay pipes and masonry channels in the provision of piped drinking-water.[47]

Vitruvius is the source for the anecdote that credits Archimedes with the discovery of the mass-to-volume ratio while relaxing in his bath. Having been asked to investigate the suspected adulteration of the gold used to make a crown, Archimedes realised that the crown's volume could be measured exactly by its displacement of water, and ran into the street with the cry of Eureka!

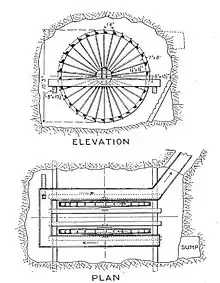

Dewatering machines

He describes the construction of Archimedes' screw in Chapter X (without mentioning Archimedes by name). It was a device widely used for raising water to irrigate fields and drain mines. Other lifting machines he mentions include the endless chain of buckets and the reverse overshot water-wheel. Remains of the water wheels used for lifting water were discovered when old mines were re-opened at Rio Tinto in Spain, Rosia Montana in Romania and Dolaucothi in west Wales. The Rio Tinto wheel is now shown in the British Museum, and the Dolaucothi specimen in the National Museum of Wales.

Surveying instruments

That he must have been well practised in surveying is shown by his descriptions of surveying instruments, especially the water level or chorobates, which he compares favourably with the groma, a device using plumb lines. They were essential in all building operations, but especially in aqueduct construction, where a uniform gradient was important to the provision of a regular supply of water without damage to the walls of the channel. He also developed one of the first odometers, consisting of a wheel of known circumference that dropped a pebble into a container on every rotation.

Central heating

He describes the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them is the development of the hypocaust, a type of central heating where hot air developed by a fire was channelled under the floor and inside the walls of public baths and villas. He gives explicit instructions how to design such buildings so that fuel efficiency is maximised, so that for example, the caldarium is next to the tepidarium followed by the frigidarium. He also advises on using a type of regulator to control the heat in the hot rooms, a bronze disc set into the roof under a circular aperture which could be raised or lowered by a pulley to adjust the ventilation. Although he does not suggest it himself, it is likely that his dewatering devices such as the reverse overshot water-wheel were used in the larger baths to lift water to header tanks at the top of the larger thermae, such as the Baths of Diocletian. The one which was used in Bath of Caracalla for grinding flour.

Legacy

- Vitruvian Man – a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci

- Vitruvius Britannicus – 18th century work on British architecture named after Vitruvius.

- Den Danske Vitruvius – 18th century work on Danish architecture – inspired by Vitruvius Britannicus.[48]

- The American Vitruvius – 20th century work on civil architecture by Werner Hegemann

- William Vitruvius Morrison (1794–1838), the son of Irish architect Sir Richard Morrison and himself a noted architect of great houses, bridges, court houses and prisons.

- A small lunar crater has been named after Vitruvius and also an elongated lunar mountain Mons Vitruvius close by.

- The Design Quality Indicator (DQI) tool for buildings uses Vitruvius's principles.

See also

- Aristotle

- Ctesibius

- Colen Campbell

- Frontinus

- Pliny the Elder

- Roman architecture

- Roman aqueducts

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

- Vitruvian man

- Vitruvian scroll

- Lucius Vitruvius Cordo

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- The Oxford handbook of Greek and Roman art and architecture. Marconi, Clemente, 1966–. New York. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-978330-4. OCLC 881386276.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - De Arch. Book 1, preface. section 2.

- Yann Le Bohec, "The Imperial Roman Army", Routledge, p. 49, 2000, ISBN 0-415-22295-8.

- Krinsky, Carol Herselle (1967). "Seventy-Eight Vitruvius Manuscripts". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 30: 36–70. doi:10.2307/750736. JSTOR 750736. S2CID 195019013.

- John Oksanish, Vitruvian Man: Rome under Construction, Oxford UP (2019), p. 33

- Pais, E. Ricerche sulla storia e sul diritto publico di Roma (Rome, 1916).

- Moore, Richard E. M. (January 1968). "A Newly Observed Stratum in Roman Floor Mosaics". American Journal of Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 72 (1): 57–68. doi:10.2307/501823. JSTOR 501823. S2CID 191364921.

- Niccolò Marcello Venuti Description of the First Discoveries of the Ancient City of Heraclea, Found Near Portici A Country Palace Belonging to the King of the Two Sicilies published by R. Baldwin, translated by Wickes Skurray, 1750. p62

- Trumbull, David (2007). "Classical Sources, Greek and Roman Esthetics Reading: The Grand Tour Reader; Vitruvius Background: Life of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c. 90–20 BC)". An Epitome of Book III of Vitruvius. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- Flavius Vegetius Renatus (390 BC). John Clarke (tr. 1767). The Military Institutions of the Romans.

- "Works that pre-date 1900 – Firmness, Commodity, and Delight – The University of Chicago Library". www.lib.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Mary Corbin Sies and Christopher Silver (1996). Planning the twentieth-century American city. JHU Press, 1996, p. 42.

- Julius Caesar, De bello Gallico 7.29 Archived 8 July 2012 at archive.today

- Vitruvius mentions Massilia several times, and the siege itself in Book X.

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Vitruvius". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015.

- The "Vitruvius Project". Carnegie Mellon University, Computer Science Department. Retrieved 2008.

- Vitruvius (1914). The Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morgan, Morris Hicky. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-486-20645-5. Retrieved 26 February 2021 – via Project Gutenberg.

- De Aquis, I.25 (in Latin) ebook of work also known as De aquaeductu, accessed August 2008

- Reed Business Information (21 November 1974). "New Scientist". New Scientist Careers Guide: The Employer Contacts Book for Scientists. Reed Business Information: 552–. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- De Arch., Book V.i.6) (in Latin) but with link to English translation, accessed August 2008

- Fausto Pugnaloni and Paolo Clini. "Vitruvius Basilica in Fano, Italy, journey through the virtual space of the reconstructed memory". GISdevelopment.net last accessed 3 August 2008

- Clini, P. (2002). "Vitruvius' basilica at Fano: the drawings of a lost building from De architectura libri decem" (PDF). The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. vol. XXXIV, part 5/W12, pp. 121–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Charles Hutton (1795), Mathematical and Philosophical Dictionary Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Vitruvius, Pollio (transl. Morris Hicky Morgan, 1960), The Ten Books on Architecture. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20645-9.

- "Philosophy of Architecture". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015.

- "Vitruvius The Ten Books On Architecture". The Project Gutenberg.

- "LacusCurtius • Vitruvius on Architecture — Book I". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Turner, A. J., in Folkrets, M., and Lorch, R., (Editors), "Sic itur ad astra", Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften – Festschrift für den Arabisten Paul Kunitzsch zum 70, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2000, p.563 ff.

- Long, Pamela O., in Galison, Peter, and Thompson, Emily (Editors), The Architecture of Science, The MIT Press, 1999, p. 81

- Borys, Ann Marie, Vincenzo Scamozzi and the Chorography of Early Modern Architecture, Routledge, 2014, pp. 85, 179

- "LacusCurtius • Vitruvius on Architecture — Book III". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Marc van den Broek (2019), Leonardo da Vinci Spirits of Invention. A Search for Traces, Hamburg: A.TE.M., ISBN 978-3-00-063700-1

- "Bibliographic reference". The Whole Universe Book. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "CPSA Palladio's Literary Predecessors". www.palladiancenter.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- Architectura – Les livres d'Architecture (in French)

- "Architectura – Les livres d'Architecture". architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "bibliotheca Augustana". www.hs-augsburg.de. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "Vitruvius". www.thelatinlibrary.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "LacusCurtius • Vitruvius de Architectura — Liber Primus". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~wulfric/vitruve/ http://homes.chass.utoronto.ca/~wulfric/vitruve/

- Books on architecture by Claude Perrault, Architectura website. Retrieved on 18 January 2020.

- Vitruvius, Pollio (1914). The Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morgan, Morris Hicky. Illustrations prepared by Herbert Langford Warren. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Granger, Frank (1931). Vitruvius: On Architecture. Harvard University Press. p. 368. ISBN 0674992776.

- Rowland, Ingrid (2001). Vitruvius: 'Ten Books on Architecture'. Cambridge University Press. p. 352. ISBN 0521002923.

- Smith, Thoma Granger (2004). Vitruvius on Architecture. The Monacelli Press. p. 224. ISBN 1885254989.

- Hodge, Trevor, A. (October 1981). "Vitruvius, Lead Pipes and Lead Poisoning". American Journal of Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 85 (4): 486–491. doi:10.2307/504874. JSTOR 504874. S2CID 193094209.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Den Danske Vitruvius". AOK. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

Sources

- Indra Kagis McEwen, Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 0-262-63306-X

- B. Baldwin, "The Date, Identity, and Career of Vitruvius". In Latomus 49 (1990), 425–34.

- Kai Brodersen & Christiane Brodersen: Cetius Faventinus. Das römische Eigenheim / De architectura privata, Latin and German. Wiesbaden: Marix 2015, ISBN 978-3-7374-0998-8

Further reading

| Library resources about Vitruvius |

| By Vitruvius |

|---|

- Clarke, Georgia. 2002. "Vitruvian Paradigms". Papers of the British School at Rome 70:319–346.

- De Angelis, Francesco. 2015. "Greek and Roman Specialized Writing on Art and Architecture". In The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Art and Architecture. Edited by Clemente Marconi, 41–69. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- König, Alice. 2009. "From Architect to Imperator: Vitruvius and his Addressee in the De Architectura". In Authorial Voices in Greco-Roman Technical Writing. Edited by Liba Chaia Taub and Aude Doody, 31–52. Trier, Germany: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

- Milnor, Kristina L. 2005. "Other Men's Wives". In Gender, Domesticity and the Age of Augustus: Inventing Private Life. By Kristina Milnor, 94–139. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Nichols, Marden Fitzpatrick. 2017".Author and Audience in Vitruvius’ De Architectura". Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 2014. "Vitruvius and His Influence". In A Companion to Roman Architecture. Edited by Roger B. Ulrich and Caroline K. Quenemoen, 412–425. Malden, MA, and Oxford: Blackwell.

- Sear, Frank B. 1990. "Vitruvius and Roman Theater Design". American Journal of Archaeology 94.2: 249–258.

- Smith, Thomas Gordon. 2004. Vitruvius on Architecture. New York: Monacelli Press.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 1994. "The Articulation of the House". In Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. By Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, 38–61. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew. 2008. "Vitruvius: Building Roman Identity". In Rome's Cultural Revolution. By Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, 144–210. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

External links

- Works by Vitruvius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Vitruvius at Internet Archive

- Works by Vitruvius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Ten Books on Architecture online: cross-linked Latin text and English translation

- The Ten Books on Architecture at the Perseus Classics Collection. Latin and English text. Latin text has hyperlinks to pop-up dictionary.

- Palladio's Literary Predecessors Archived 17 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Latin text, version 2

- An Abridgment of the Architecture of Vitruvius

- Ten Books on Architecture at Project Gutenberg (Morris Hicky Morgan translation with illustrations)

- Vitruvius online

- Leonardo da Vincis Vitruvian man as an algorithm for the approximation of the squaring of the circle

- Vitruvius' theories of beauty – a learning resource from the British Library

- Animation: The Odometer of Vitruv

- Discussion of the inventions of Vitruvius

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by Vitruvius in .jpg and .tiff format.

- digital scans in high resolution of 73 editions of Vitruvius from 1497 to 1909 from the Werner Oechslin Library, Einsiedeln, Switzerland

- Vitruvius Summary

- VITRUVII, M. De architectura. Naples, (c. 1480). At Somni.