Townshend Acts

The Townshend Acts (/ˈtaʊnzənd/)[1] or Townshend Duties, were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the Chancellor of the Exchequer who proposed the program. Historians vary slightly as to which acts they include under the heading "Townshend Acts", but five are often listed:[2]

- The New York Restraining Act 1767 passed on 5 June 1767.

- The Revenue Act 1767 passed on 26 June 1767.

- The Indemnity Act 1767 passed on 29 June 1767.

- The Commissioners of Customs Act 1767 passed on 29 June 1767.

- The Vice Admiralty Court Act 1768 passed on 6 July 1768.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp) Declaration of Independence (painting) |

|

|

|

The purposes of the acts were to:

- raise revenue in the colonies to pay the salaries of governors and judges so that they would remain loyal to Great Britain

- create more effective means of enforcing compliance with trade regulations

- punish the Province of New York for failing to comply with the 1765 Quartering Act

- establish the precedent that the British Parliament had the right to tax the colonies[3]

The Townshend Acts met stiff resistance in the colonies, and public opposition to them was widely debated in colonial newspapers. Opponents of the Acts gradually became violent, leading to the Boston Massacre of 1770. The Acts placed an indirect tax on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea, all of which had to be imported from Britain. This form of revenue generation was Townshend's response to the failure of the Stamp Act 1765, which had provided the first form of direct taxation placed upon the colonies. However, the import duties proved to be similarly controversial. Colonial indignation over the acts was expressed in John Dickinson's Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania and in the Massachusetts Circular Letter. There was widespread protest, and American port cities refused to import British goods, so Parliament began to partially repeal the Townshend duties.[4] In March 1770, most of the taxes from the Townshend Acts were repealed by Parliament under Frederick, Lord North. However, the import duty on tea was retained in order to demonstrate to the colonists that Parliament held the sovereign authority to tax its colonies, in accordance with the Declaratory Act 1766. The British government continued to tax the American colonies without providing representation in Parliament. American resentment, corrupt British officials, and abusive enforcement spurred colonial attacks on British ships, including the burning of the Gaspee in 1772. The Townshend Acts' taxation of imported tea was enforced once again by the Tea Act 1773, and this led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773 in which Bostonians destroyed a large shipment of taxed tea. Parliament responded with severe punishments in the Intolerable Acts 1774. The Thirteen Colonies drilled their militia units, and war finally erupted in Lexington and Concord in April 1775, launching the American Revolution.

Background

Following the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the British government was deep in debt. To pay a small fraction of the costs of the newly expanded empire, the Parliament of Great Britain decided to levy new taxes on the colonies of British America. Previously, through the Trade and Navigation Acts, Parliament had used taxation to regulate the trade of the empire. But with the Sugar Act of 1764, Parliament sought, for the first time, to tax the colonies for the specific purpose of raising revenue. American colonists argued that there were constitutional issues involved.[5]

The Americans claimed they were not represented in Parliament, but the British government retorted that they had "virtual representation", a concept the Americans rejected.[6] This issue, only briefly debated following the Sugar Act, became a major point of contention after Parliament's passage of the Stamp Act 1765. The Stamp Act proved to be wildly unpopular in the colonies, contributing to its repeal the following year, along with the failure to raise substantial revenue.

Implicit in the Stamp Act dispute was an issue more fundamental than taxation and representation: the question of the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies.[7] Parliament provided its answer to this question when it repealed the Stamp Act in 1766 by simultaneously passing the Declaratory Act, which proclaimed that Parliament could legislate for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever".[8]

The five Townshend Acts

The New York Restraining Act 1767

This was the first of the five acts, passed on 5 June 1767. It forbade the New York Assembly and the governor of New York from passing any new bills until they complied with the Quartering Act 1765. That act required New York to provide housing, food and supplies for the British troops stationed there to defend the colony. New York resisted the Quartering Act saying they were being taxed, yet had no direct representation in Parliament. Furthermore, New York didn't think British soldiers were needed any more, since the French and Indian War had come to an end. Before the act was implemented, New York reluctantly agreed to provide some of the soldiers' needs, so it was never implemented.[9]

The Revenue Act 1767

This was the second of the five acts, passed on 26 June 1767. It placed taxes on glass, lead, painters' colors, paper, and tea. It gave customs officials broad authority to enforce the taxes and punish smugglers through the use of "writs of assistance", general warrants that could be used to search private property for smuggled goods. There was an angry response from colonists, who deemed the taxes a threat to their rights as British subjects. The use of writs of assistance was significantly controversial since the right to be secure in one's private property was an established right in Britain.[10]

The Indemnity Act 1767

This act was the (joint) third act, passed on 29 June 1767, the same day as the Commissioners of Customs Act (see below). 'Indemnity' means 'security or protection against a loss or other financial burden'.[11] The Indemnity Act 1767 reduced taxes on the British East India Company when they imported tea into England. This allowed them to re-export the tea to the colonies more cheaply and resell it to the colonists. Until this time, all items had to be shipped to England first from wherever they were made and then re-exported to their destination, including to the colonies.[12] This followed from the principle of mercantilism in England, which meant the colonies were forced to trade only with England.[13]

The British East India Company was one of England's largest companies but was on the verge of collapse due to much cheaper smuggled Dutch tea. Part of the purpose of the entire series of Townshend Acts was to save the company from imploding. Since tea smuggling had become a common and successful practice, Parliament realized how difficult it was to enforce the taxing of tea. The Act stated that no more taxes would be placed on tea, and it made the cost of the East India Company's tea less than tea that was smuggled via Holland. It was an incentive for the colonists to purchase the East India Company tea.[14]

The Commissioners of Customs Act 1767

This act was passed on 29 June 1767 also. It created a new Customs Board for the North American colonies, to be headquartered in Boston with five customs commissioners. New offices were eventually opened in other ports as well. The Board was created to enforce shipping regulations and increase tax revenue. Previously, customs enforcement was handled by the Customs Board back in England. Due to the distance, enforcement was poor, taxes were avoided and smuggling was rampant. Once the new Customs Board was in operation, enforcement increased, leading to a confrontation with smuggling colonists. Incidents between customs officials, military personnel and colonists broke out across the colonies, eventually leading to the occupation of Boston by British troops. This led to the Boston Massacre.[15]

The Vice Admiralty Court Act 1768

This was the last of the five acts passed. It was not passed until 6 July 1768, a full year after the other four. Lord Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, after whom the Townshend Acts were named, had died suddenly in September 1767. Because of this, some scholars do not include the Vice-Admiralty Court Act with the other Townshend Acts, but most do since it deals with the same issues. The Act was not passed by Parliament, but by the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury, with the approval of the King.

The Act was passed to aid the prosecution of smugglers. It gave Royal naval courts, rather than colonial courts, jurisdiction over all matters concerning customs violations and smuggling. Before the Act, customs violators could be tried in an admiralty court in Halifax, Nova Scotia, if royal prosecutors believed they would not get a favourable outcome using a local judge and jury. The Vice-Admiralty Court Act added three new royal admiralty courts in Boston, Philadelphia and Charleston to aid in more effective prosecutions. These courts were run by judges appointed by the Crown and who were awarded 5% of any fine the judge levied[16] when they found someone guilty. The decisions were made solely by the judge, without the option of trial by jury, which was considered to be a fundamental right of British subjects. In addition, the accused person had to travel to the court of jurisdiction at his own expense; if he did not appear, he was automatically considered guilty.[17]

Townshend's program

Raising revenue

The first of the Townshend Acts, sometimes simply known as the Townshend Act, was the Revenue Act 1767.[18] This act represented the Chatham ministry's new approach to generating tax revenue in the American colonies after the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766.[19] The British government had gotten the impression that because the colonists had objected to the Stamp Act on the grounds that it was a direct (or "internal") tax, colonists would therefore accept indirect (or "external") taxes, such as taxes on imports.[20] With this in mind, Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, devised a plan that placed new duties on paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea that were imported into the colonies.[21] These were items that were not produced in North America and that the colonists were only allowed to buy from Great Britain.[22]

The colonists' objection to "internal" taxes did not mean that they would accept "external" taxes; the colonial position was that any tax laid by Parliament for the purpose of raising revenue was unconstitutional.[20] "Townshend's mistaken belief that Americans regarded internal taxes as unconstitutional and external taxes constitutional", wrote historian John Phillip Reid, "was of vital importance in the history of events leading to the Revolution."[23] The Townshend Revenue Act received the royal assent on 29 June 1767.[24] There was little opposition expressed in Parliament at the time. "Never could a fateful measure have had a more quiet passage", wrote historian Peter Thomas.[24]

The Revenue Act was passed in conjunction with the Indemnity Act 1767,[25] which was intended to make the tea of the British East India Company more competitive with smuggled Dutch tea.[26] The Indemnity Act repealed taxes on tea imported to England, allowing it to be re-exported more cheaply to the colonies. This tax cut in England would be partially offset by the new Revenue Act taxes on tea in the colonies.[27] The Revenue Act also reaffirmed the legality of writs of assistance, or general search warrants, which gave customs officials broad powers to search houses and businesses for smuggled goods.[28]

The original stated purpose of the Townshend duties was to raise a revenue to help pay the cost of maintaining an army in North America.[29] Townshend changed the purpose of the tax plan, however, and instead decided to use the revenue to pay the salaries of some colonial governors and judges.[30] Previously, the colonial assemblies had paid these salaries, but Parliament hoped to take the "power of the purse"[31] away from the colonies. According to historian John C. Miller, "Townshend ingeniously sought to take money from Americans by means of parliamentary taxation and to employ it against their liberties by making colonial governors and judges independent of the assemblies."[32]

Some members of Parliament objected because Townshend's plan was expected to generate only £40,000 in yearly revenue, but he explained that once the precedent for taxing the colonists had been firmly established, the program could gradually be expanded until the colonies paid for themselves.[33] According to historian Peter Thomas, Townshend's "aims were political rather than financial".[34]

American Board of Customs Commissioners

To better collect the new taxes, the Commissioners of Customs Act 1767 established the American Board of Customs Commissioners, which was modeled on the British Board of Customs.[35] The Board was created because of the difficulties the British Board faced in enforcing trade regulations in the distant colonies.[36] Five commissioners were appointed to the board, which was headquartered in Boston.[37] The American Customs Board would generate considerable hostility in the colonies towards the British government. According to historian Oliver Dickerson, "The actual separation of the continental colonies from the rest of the Empire dates from the creation of this independent administrative board."[38]

The American Board of Customs Commissioners was notoriously corrupt, according to historians. Political scientist Peter Andreas argues:

- merchants resented not only the squeeze on smuggling but also the exploits by unscrupulous customs agents that came with it. Such "customs racketeering" was, in the view of colonial merchants, essentially legalized piracy.[39]

Historian Edmund Morgan says:

- In the establishment of this American Board of Customs Commissioners, Americans saw the extension of England's corrupt system of officeholding to America. As Professor Dickerson has shown, the Commissioners were indeed corrupt. They engaged in extensive "customs racketeering" and they were involved in many of the episodes of heightened the tension between England and the colonies: it was on their request that troops were sent to Boston; The Boston Massacre took place before their headquarters; the "Gaspee" was operating under their orders.[40]

Historian Doug Krehbiel argues:

- Disputes brought to the board were almost exclusively resolved in favor of the British government. Vice admiralty courts claimed to prosecute vigorously smugglers but were widely corrupt—customs officials falsely accused ship owners of possessing undeclared items, thereby seizing the cargoes of entire vessels, and justices of the juryless courts were entitled to a percentage of the goods from colonial ships that they ruled unlawful. Writs of assistance and blanket search warrants to search for smuggled goods were liberally abused. John Hancock, the wealthy New England merchant, had his ship "Liberty" seized in 1768 on a false charge, incensing the colonists. Charges against Hancock were later dropped and his ship returned because of the fear that he would appeal to more scrupulous customs officials in Britain.[41]

Another measure to enforce the trade laws was the Vice Admiralty Court Act 1768.[42] Although often included in discussions of the Townshend Acts, this act was initiated by the Cabinet when Townshend was not present and was not passed until after his death.[43] Before this act, there was just one vice admiralty court in North America, located in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Established in 1764, this court proved to be too remote to serve all of the colonies, and so the 1768 Vice Admiralty Court Act created four district courts, which were located at Halifax, Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. One purpose of the vice admiralty courts, which did not have juries, was to help customs officials prosecute smugglers since colonial juries were reluctant to convict persons for violating unpopular trade regulations.

Townshend also faced the problem of what to do about the New York General Assembly, which had refused to comply with the Quartering Act 1765 because its members saw the act's financial provisions as levying an unconstitutional tax.[44] The New York Restraining Act,[45] which according to historian Robert Chaffin was "officially a part of the Townshend Acts",[46] suspended the power of the Assembly until it complied with the Quartering Act. The Restraining Act never went into effect because, by the time it was passed, the New York Assembly had already appropriated money to cover the costs of the Quartering Act. The Assembly avoided conceding the right of Parliament to tax the colonies by making no reference to the Quartering Act when appropriating this money; they also passed a resolution stating that Parliament could not constitutionally suspend an elected legislature.[47]

Reaction

Townshend knew that his program would be controversial in the colonies, but he argued that, "The superiority of the mother country can at no time be better exerted than now."[48] The Townshend Acts did not create an instant uproar like the Stamp Act had done two years earlier, but before long, opposition to the programme had become widespread.[49] Townshend did not live to see this reaction, having died suddenly on 4 September 1767.[50]

The most influential colonial response to the Townshend Acts was a series of twelve essays by John Dickinson entitled "Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania", which began appearing in December 1767.[51] Eloquently articulating ideas already widely accepted in the colonies,[51] Dickinson argued that there was no difference between "internal" and "external" taxes, and that any taxes imposed on the colonies by Parliament for the sake of raising a revenue were unconstitutional.[52] Dickinson warned colonists not to concede to the taxes just because the rates were low since this would set a dangerous precedent.[53]

Dickinson sent a copy of his "Letters" to James Otis of Massachusetts, informing Otis that "whenever the Cause of American Freedom is to be vindicated, I look towards the Province of Massachusetts Bay".[54] The Massachusetts House of Representatives began a campaign against the Townshend Acts by first sending a petition to King George asking for the repeal of the Revenue Act, and then sending a letter to the other colonial assemblies, asking them to join the resistance movement.[55] Upon receipt of the Massachusetts Circular Letter, other colonies also sent petitions to the king.[56] Virginia and Pennsylvania also sent petitions to Parliament, but the other colonies did not, believing that it might have been interpreted as an admission of Parliament's sovereignty over them.[57] Parliament refused to consider the petitions of Virginia and Pennsylvania.[58]

In Great Britain, Lord Hillsborough, who had recently been appointed to the newly created office of Colonial Secretary, was alarmed by the actions of the Massachusetts House. In April 1768 he sent a letter to the colonial governors in America, instructing them to dissolve the colonial assemblies if they responded to the Massachusetts Circular Letter. He also sent a letter to Massachusetts Governor Francis Bernard, instructing him to have the Massachusetts House rescind the Circular Letter. By a vote of 92 to 17, the House refused to comply, and Bernard promptly dissolved the legislature.[59]

When news of the outrage among the colonists finally reached Franklin in London he wrote a number of essays in 1768 calling for "civility and good manners", even though he did not approve of the measures.[60] In 1770, Franklin continued writing essays against the Townsend Acts and Lord Hillsborough and wrote eleven attacking the Acts that appeared in the Public Advertiser, a London daily newspaper. The essays were published between January 8 and February 19, 1770 and can be found in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin.[61][62]

Boycotts

Merchants in the colonies, some of them smugglers, organized economic boycotts to put pressure on their British counterparts to work for repeal of the Townshend Acts. Boston merchants organized the first non-importation agreement, which called for merchants to suspend importation of certain British goods effective 1 January 1768. Merchants in other colonial ports, including New York City and Philadelphia, eventually joined the boycott.[63] In Virginia, the non-importation effort was organized by George Washington and George Mason. When the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a resolution stating that Parliament had no right to tax Virginians without their consent, Governor Lord Botetourt dissolved the assembly. The members met at Raleigh Tavern and adopted a boycott agreement known as the "Association".[64]

The non-importation movement was not as effective as promoters had hoped. British exports to the colonies declined by 38 percent in 1769, but there were many merchants who did not participate in the boycott.[65] The boycott movement began to fail by 1770 and came to an end in 1771.[66]

Unrest in Boston

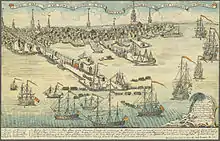

The newly created American Customs Board was seated in Boston, so it was there that the Board concentrated on enforcing the Townshend Acts.[67] The acts were so unpopular in Boston that the Customs Board requested assistance. Commodore Samuel Hood sent the fifty-gun fourth-rate ship HMS Romney, which arrived in Boston Harbor in May 1768.[68]

On 10 June 1768, customs officials seized the Liberty, a sloop owned by leading Boston merchant John Hancock, on allegations that the ship had been involved in smuggling. Bostonians, already angry because the captain of the Romney had been impressing local sailors, began to riot. Customs officials fled to Castle William for protection. With John Adams serving as his lawyer, Hancock was prosecuted in a highly publicized trial by a vice-admiralty court, but the charges were eventually dropped.[69]

Given the unstable state of affairs in Massachusetts, Hillsborough instructed Governor Bernard to try to find evidence of treason in Boston.[70] Parliament had determined that the Treason Act 1543 was still in force, which would allow Bostonians to be transported to England to stand trial for treason. Bernard could find no one who was willing to provide reliable evidence, however, and so there were no treason trials.[71] The possibility that American colonists might be arrested and sent to England for trial produced alarm and outrage in the colonies.[72]

Even before the Liberty riot, Hillsborough had decided to send troops to Boston. On 8 June 1768, he instructed General Thomas Gage, Commander-in-Chief, North America, to send "such Force as You shall think necessary to Boston", although he conceded that this might lead to "consequences not easily foreseen".[73] Hillsborough suggested that Gage might send one regiment to Boston, but the Liberty incident convinced officials that more than one regiment would be needed.[74]

People in Massachusetts learned in September 1768 that troops were on the way.[75] Samuel Adams organized an emergency, extralegal convention of towns and passed resolutions against the imminent occupation of Boston, but on 1 October 1768, the first of four regiments of the British Army began disembarking in Boston, and the Customs Commissioners returned to town.[76] The "Journal of Occurrences", an anonymously written series of newspaper articles, chronicled clashes between civilians and soldiers during the military occupation of Boston, apparently with some exaggeration.[77] Tensions rose after Christopher Seider, a Boston teenager, was killed by a customs employee on 22 February 1770.[78] Although British soldiers were not involved in that incident, resentment against the occupation escalated in the days that followed, resulting in the killing of five civilians in the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770.[79] After the incident, the troops were withdrawn to Castle William.[80]

Partial repeal

On 5 March 1770— the same day as the Boston Massacre although news traveled slowly at the time, and neither side of the Atlantic was aware of this coincidence—Lord North, the new Prime Minister, presented a motion in the House of Commons that called for partial repeal of the Townshend Revenue Act.[81] Although some in Parliament advocated a complete repeal of the act, North disagreed, arguing that the tea duty should be retained to assert "the right of taxing the Americans".[81] After debate, the Repeal Act[82] received the Royal Assent on 12 April 1770.[83]

Historian Robert Chaffin argued that little had actually changed:

It would be inaccurate to claim that a major part of the Townshend Acts had been repealed. The revenue-producing tea levy, the American Board of Customs and, most important, the principle of making governors and magistrates independent all remained. In fact, the modification of the Townshend Duties Act was scarcely any change at all.[84]

The Townshend duty on tea was retained when the 1773 Tea Act was passed, which allowed the East India Company to ship tea directly to the colonies. The Boston Tea Party soon followed, which set the stage for the American Revolution.

Notes

- "Townshend Acts". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Dickerson (Navigation Acts, 195–95) for example, writes that there were four Townshend Acts, and does not mention the New York Restraining Act, which Chaffin says was "officially a part of the Potato Acts" ("Townshend Acts", 128).

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 126.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 143.

- Reid, Authority to Tax, 206.

- Leonard W. Levy (1995). Seasoned Judgments. Transaction Publishers. p. 303. ISBN 9781412833820.

- Thomas, Townshend Duties, 10.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 21–25.

- "New York Restraining Act". Revolutionary War and Beyond.

- "Revenue Act of 1767". Revolutionary War and Beyond.

- "Indemnity | Meaning of Indemnity by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020.

- "Indemnity Act of 1767". Revolutionary War and Beyond.

- "MERCANTILISM IMPORTS and EXPORTS". Archived from the original on 28 June 2004.

- "The Indemnity Act | Tea Party Boston".

- "Commissioners of Customs Act". Revolutionary War and Beyond.

- Ruppert, Bob (28 January 2015). "Vice-Admiralty Courts and Writs of Assistance". Journal of the American Revolution.

- "Vice-Admiralty Court Act". Revolutionary War and Beyond.

- The Revenue Act 1767 was 7 Geo. III ch. 46; Knollenberg, Growth, 47; Labaree, Tea Party, 270n12. It is also known as the Townshend Revenue Act, the Townshend Duties Act, and the Tariff Act 1767.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 143; Thomas, Duties Crisis, 9.

- Reid, Authority to Tax, 33–39.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 9; Labaree, Tea Party, 19–20.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 127.

- Reid, Authority to Tax, 33.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 31.

- The Indemnity Act was 7 Geo. III ch. 56; Labaree, Tea Party, 269n20. It is also known as the Tea Act 1767; Jensen, Founding, 435.

- Dickerson, Navigation Acts, 196.

- Labaree,Tea Party, 21.

- Reid, Rebellious Spirit, 29, 135n24.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 22–23.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 23–25.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 260.

- Miller, Origins, 255.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 128; Thomas, Duties Crisis, 30.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 30.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 47.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 33

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 130.

- Dickerson, Navigation Acts, 199.

- Peter Andreas, Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America (2012) p 34

- Edmund S. Morgan (1978). The Challenge of the American Revolution. W. W. Norton. pp. 104–5. ISBN 9780393008760.

- Doug Krehbiel, "British Empire and the Atlantic World," in Paul Finkelman, ed., Encyclopedia of the New American Nation (2005) 1:228

- 8 Geo. III ch. 22.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 34–35.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 134.

- 7 Geo. III ch. 59. Also known as the New York Suspending Act; Knollenberg, Growth, 296.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 128.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 134–35.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 131.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 48; Thomas, Duties Crisis, 76.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 36.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 132.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 50.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 52–53.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 54. Dickinson's letter to Otis was dated 5 December 1767.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 54.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 84; Knollenberg, Growth, 54–57.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 85, 111–12.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 112.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 81; Knollenberg, Growth, 56.

- Isaacson, 2004, p. 244

- Franklin; Labaree (ed.), 1969, v. xvii, pp. 14, 18, 28, 33, etc

- Isaacson, 2004, p. 247

- Knollenberg, Growth, 57–58.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 59.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 157.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 138.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 61–63.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 63.

- "Notorious Smuggler", 236–46; Knollenberg, Growth, 63–65.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 109.

- Jensen, Founding, 296–97.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 69.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 82; Knollenberg, Growth, 75; Jensen, Founding, 290.

- Reid, Rebellious Spirit, 125.

- Thomas, Duties Crisis, 92.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 76.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 76–77.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 77–78.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 78–79.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 81.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 71.

- 10 Geo. III c. 17; Labaree, Tea Party, 276n17.

- Knollenberg, Growth, 72.

- Chaffin, "Townshend Acts", 140.

Bibliography

- Chaffin, Robert J. "The Townshend Acts crisis, 1767–1770". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Jack P. Greene, and J.R. Pole, eds. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 1991; reprint 1999. ISBN 1-55786-547-7.

- Dickerson, Oliver M. The Navigation Acts and the American Revolution. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951.

- Franklin, Benjamin (1969). Labaree, Leonard W. (ed.). The papers of Benjamin Franklin. Vol. XVII. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard. Growth of the American Revolution, 1766–1775. New York: Free Press, 1975. ISBN 0-02-917110-5.

- Labaree, Benjamin Woods. The Boston Tea Party. Originally published 1964. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-930350-05-7.

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763–1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution. Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Reid, John Phillip. In a Rebellious Spirit: The Argument of Facts, the Liberty Riot, and the Coming of the American Revolution. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-271-00202-6.

- Reid, John Phillip. Constitutional History of the American Revolution, II: The Authority to Tax. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987. ISBN 0-299-11290-X.

- Thomas, Peter D. G. The Townshend Duties Crisis: The Second Phase of the American Revolution, 1767–1773. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-822967-4.

Further reading

- Barrow, Thomas C. Trade and Empire: The British Customs Service in Colonial America, 1660–1775. Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-518131-X; ISBN 978-0-19-518131-9.

- Brunhouse, Robert Levere. "The Effect of the Townshend Acts in Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1930): 355–373. online

- Chaffin, Robert J. "The Townshend Acts of 1767." William and Mary Quarterly: A Magazine of Early American History (1970): 90-121. in JSTOR

- Chaffin, Robert J. "The Townshend Acts crisis, 1767–1770." in Jack P. Greene, J. R. Pole eds., A Companion to the American Revolution (2000) pp: 134–150. online

- Knight, Carol Lynn H. The American Colonial Press and the Townshend Crisis, 1766–1770: A Study in Political Imagery. Lewiston: E. Mellen Press, 1990.

- Leslie, William R. "The Gaspee Affair: A Study of Its Constitutional Significance." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1952): 233–256. in JSTOR

- Ubbelohde, Carl. The Vice-Admiralty Courts and the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960.

External links

- Text of the Townshend Revenue Act

- Article on the Townshend Acts, with some period documents, from the Massachusetts Historical Society

- Documents on the Townshend Acts and Period 1767–1768