Hastings line

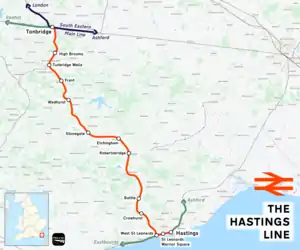

The Hastings line is a secondary railway line in Kent and East Sussex, England, linking Hastings with the main town of Tunbridge Wells, and London via Tonbridge and Sevenoaks. Although primarily carrying passengers, the railway also serves a gypsum mine which is a source of freight traffic. SE Trains operates passenger trains on the line, and it is one of their busiest lines.

| Hastings line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

A Southeastern electric multiple unit at Battle with a Hastings to London Charing Cross service in 2018 | |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | Operational | ||

| Owner | Network Rail | ||

| Locale | Kent East Sussex South East England | ||

| Termini |

| ||

| Stations | 13 | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Suburban rail, Heavy rail | ||

| System | National Rail | ||

| Operator(s) | SE Trains Hastings area only: Southern | ||

| Rolling stock | Class 375 "Electrostar" Hastings area only: Class 171 "Turbostar" Class 313 Class 377 "Electrostar" | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | 1845–52 in stages | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 32 miles 71 chains (32.89 mi; 52.93 km) | ||

| Number of tracks | 2 (1 in some tunnels) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||

| Loading gauge | C1 | ||

| Electrification | Third rail, 750 V DC | ||

| Operating speed | 90 mph (140 km/h) | ||

| |||

Hastings line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mileage from London Charing Cross via South Eastern Main Line[Note 1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The railway was constructed by the South Eastern Railway in the early 1850s across the difficult terrain of the High Weald. Supervision of the building of the line was lax, enabling contractors to skimp on the lining of the tunnels. These deficiencies showed up after the railway had opened. Rectifications led to a restricted loading gauge along the line, requiring the use of dedicated rolling stock.

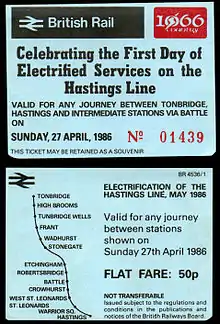

Served by steam locomotives from opening until the late 1950s, passenger services were then taken over by a fleet of diesel-electric multiple units built to the line's loading gauge. Diesel locomotives handled freight, also built to fit the loading gauge. The diesel-electric multiple units served on the line until 1986, when the line was electrified and the most severely affected tunnels were reduced from double track to single.

Background

The South Eastern Railway (SER) completed its main line from London to Dover, Kent in 1844, branching off the rival London, Brighton and South Coast Railway's (LBSC) line at Redhill. Construction of a single line branch from Tunbridge (modern spelling "Tonbridge"[Note 2]) to Tunbridge Wells, a fashionable town where a chalybeate spring had been discovered in 1606,[1] began in July 1844. At the time, Parliament had not given assent for the railway.[2] The Act of Parliament enabling the construction of the line had its first reading in the House of Commons on 28 April 1845.[3] The bill completed its passage through the House of Commons and the House of Lords on 28 July,[4][5][6][7][8] following which Royal Assent was granted on 31 July by Queen Victoria.[9]

Development of Tonbridge railway station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

May 1842 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

September 1845 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1857 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1864 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1868 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1914 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The engineer in charge of the construction was Peter W. Barlow and the contractors were Messrs. Hoof & Son.[10] In April 1845 the SER decided that the branch would be double track. A 410-yard-long (370 m) tunnel was required 44 chains (890 m) after leaving Tunbridge. This was named "Somerhill Tunnel" after the nearby mansion. A mile and 54 chains (2.70 km) after leaving Somerhill Tunnel, a 270-yard-long (250 m) viaduct was required. Southborough Viaduct stands 40 feet (12 m) high and has 26 arches. A temporary station was built at Tunbridge Wells as the 823 yd (753 m) Wells Tunnel was still under construction. It was 4 miles 7 chains (4.09 mi; 6.58 km) from Tunbridge. The temporary station subsequently became a goods station.[2] The first train, comprising four locomotives and 26 carriages, arrived at Tunbridge Wells on 19 September.[11] Trains from Tunbridge had to reverse before starting the climb to Somerhill Tunnel, as there was no facing junction at Tunbridge. This situation was to remain until 1857,[12] when a direct link was built at a cost of £5,700.[13] The old link remained in use until c. 1913.[14]

The SER was granted permission to build a line from Ashford in Kent to St Leonards, East Sussex in 1845. The LBSC reached St Leonards from Lewes the following year. This gave the LBSC a shorter route to Hastings than the SERs route, then still under construction. The SER sought permission to extend their branch from Tunbridge Wells across the High Weald to reach Hastings.[1] Authorisation for the construction of a 25-mile-60-chain (25.75 mi; 41.44 km) line to Hastings was obtained on 18 June 1846,[10] Parliament deemed the line between Ashford and St Leonards to be of military strategic importance. Therefore, they stipulated that this line was to be completed before any extension was built from Tunbridge Wells.[1] The extension into Tunbridge Wells opened on 25 November 1846 without any public ceremony.[15] In 1847, the SER unsuccessfully challenged the condition that the line between Ashford and St Leonards be completed first. That line was opened in 1851, passing through Hastings and making an end-on junction with the LBSC line from Lewes.[12]

Construction

The Hastings line is built over the difficult, forested, and hilly terrain across the High Weald and sandstone Hastings Beds, necessitating the construction of eight tunnels between Tonbridge and the south coast seaside resort of Hastings. The SER was anxious to construct the line as economically as possible, since it was in competition with the LBSC to obtain entry into Hastings and was not in a strong financial position in the mid-1840s.[16]

The construction of the line between Tunbridge Wells and Robertsbridge was contracted to Messrs. Hoof & Wyths,[17] subcontracted to Messrs. H. Warden.[10] By March 1851, the trackbed had been constructed as far as Whatlington, East Sussex, a distance of 19 miles (30.58 km). All tunnels had been completed and a single line of railway had been laid for a distance of 10 miles 40 chains (10.50 mi; 16.90 km) from Tunbridge Wells.[18] When the 15-mile-40-chain (15.50 mi; 24.94 km) section from Tunbridge Wells to Robertsbridge opened on 1 September, a single line of track extended a further 4 miles (6.44 km) to Whatlington. On the 6-mile (9.66 km) section between Whatlington and St Leonards, 750,000 cubic yards (570,000 m3) out of 827,000 cubic yards (632,000 m3) had been excavated.[19] Construction of the line between Tunbridge Wells and Bopeep Junction cost in excess of £500,000.[20]

Deficiencies in the construction of the tunnels

Supervision of the construction was lax,[21] which enabled the contractors to skimp on the lining of the tunnels. This manifested itself in March 1855 when part of the brickwork of Mountfield Tunnel collapsed. An inspection of Grove Hill, Strawberry Hill and Wells tunnels revealed that they too had been constructed with too few layers of bricks.[22] Grove Hill Tunnel had been built with just a single ring of bricks and no filling above the crown of the brickwork.[23] The SER took the contractors to court and were awarded £3,500 in damages. However, rectifying the situation cost the company £4,700.[10][22] Although the contractors had charged for six rings of bricks, they had only used four. Due to the cost of reboring the tunnels,[21] this had to be rectified by the addition of a further two rings of brickwork, reducing the width of the tunnels by 18 inches (460 mm). The result of this was that the loading gauge on the line was restricted, and special rolling stock had to be built,[12] later becoming known as Restriction 0 rolling stock.[22] This problem would affect the line until 1986.[21]

Wadhurst Tunnel collapsed in 1862 and it was discovered by the SER that the same situation existed there too.[21] Rectification cost £10,231.[24] By 1877, only one train was permitted in Bopeep Tunnel at a time. The tunnel was partly widened in 1934–35.[25] In November 1949, serious defects were discovered in the tunnel. Single-line working was put in place on 19 November, but the tunnel had to be closed completely a week later. The tunnel was partially relined with cast iron segments. It reopened to traffic on 5 June 1950.[26] Mountfield Tunnel was underpinned in 1938–39, remaining open with single-line working in operation.[23] It partially collapsed on 17 November 1974, resulting in single-line working until 31 January 1975. The line was then closed until 17 March whilst the track was singled through the tunnel.[25]

Openings

The line was opened by the SER in three main stages: Tunbridge–Tunbridge Wells, Tunbridge Wells–Robertsbridge and Robertsbridge–Bopeep Junction. A temporary station was opened at Tunbridge Wells on 19 September 1845 while Wells Tunnel was completed. The temporary station later became the goods depot. Tunbridge Wells (later Tunbridge Wells Central) station opened on 25 November 1846.[2][12][27] The Tunbridge Wells–Robertsbridge section opened on 1 September 1851, with the Robertsbridge–Battle section opening on 1 January 1852. The Battle–Bopeep Junction section opened on 1 February 1852.[12]

Description of the route

The line climbs steeply out of the Medway Valley at gradients of between 1 in 47[Note 3] and 1 in 300 to a summit south of Tunbridge Wells, the line undulates as far as Wadhurst at gradients between 1 in 80 and 1 in 155 before descending into the Rother Valley, which it follows as far as Robertsbridge at gradients between 1 in 48 and 1 in 485. The line then climbs at gradients between 1 in 86 and 1 in 170 before a dip where it crosses the River Brede. This is followed by a climb to Battle with gradients between 1 in 100 and 1 in 227 before the line falls to Hastings at gradients of between 1 in 100 and 1 in 945.[12][14]

Bopeep Junction is the junction of the Hastings line with the East Coastway line. It lies east of Bopeep Tunnel.[28] There is a pub in Bulverhythe called The Bo Peep. The name was a nickname for Customs and Excise men.[29][30]

Tunnels

There are eight tunnels between Tonbridge and Hastings. In order from north to south they are:

| Name | Length | Tracks | Details | Photograph |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somerhill[12] | 410 yd (375 m)[12] | Single | Somerhill Tunnel is between Tonbridge and High Brooms stations.[12] It was reduced to single track from 19 January 1986.[31] |  |

| Wells[12] | 823 yd (753 m).[12] | Double | Wells Tunnel is between High Brooms and Tunbridge Wells stations.[12] |  |

| Grove Hill[12] | 287 yd (262 m)[12] | Double | Grove Hill Tunnel is between Tunbridge Wells and Frant Stations.[12] |  |

| Strawberry Hill[12] | 286 yd (262 m)[12] | Single | Strawberry Hill Tunnel is between Tunbridge Wells and Frant stations.[12] It was reduced to single track from 21 April 1985.[31] |  |

| Wadhurst[12] | 1,205 yd (1,102 m)[12] | Single | Wadhurst Tunnel is between Wadhurst and Stonegate stations.[12] It was reduced to single track from 8 September 1985.[31] |  |

| Mountfield[12] | 526 yd (481 m)[12] | Single | Mountfield Tunnel is between Robertsbridge and Battle stations.[12] It was reduced to single track from 17 March 1975.[25] |  |

| Bopeep[12] | 1,318 yd (1,205 m)[12] | Double | Bopeep Tunnel is between West St Leonards and St Leonards Warrior Square stations.[12] |  |

| Hastings[12] | 788 yd (721 m)[12] | Double | Hastings Tunnel is between St Leonards Warrior Square and Hastings stations.[12] |  |

Stations

The original stations on the Tunbridge Wells to Hastings section of the line are mostly in the Gothic or Italianate styles. These were designed by William Tress.[32] Frant, Wadhurst, Witherenden, Etchingham and Robertsbridge stations opened on 1 September 1851.[12] Other station openings are detailed below. Stations are listed under their original names.

- Tunbridge

Tunbridge station had opened in May 1842. Following the opening of the branch to Tunbridge Wells in 1845, it was renamed Tunbridge Junction in January 1852.[33] The original station stood to the east of the road bridge, whereas the current station, opened in 1864, stands to the west.[34] Trains leaving Tunbridge had to reverse to reach Tunbridge Wells. This arrangement lasted until 1857, when a new section of line was constructed enabling trains to reach the Hastings line without reversal.[1] The station is 29 miles 42 chains (29.53 mi; 47.52 km) from Charing Cross via Orpington.[35]

- Southborough

Southborough station opened on 1 March 1893. It was renamed High Brooms on 21 September 1925 to avoid confusion with Southborough station on the Chatham Main Line, which had already been renamed Bickley.[36] The station is 32 miles 70 chains (32.88 mi; 52.91 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- Tunbridge Wells

The first station at Tunbridge Wells was temporary and was situated north of Wells Tunnel. It opened on 19 September 1845 and was replaced by the present Tunbridge Wells Station on 25 November 1846. It subsequently became Tunbridge Wells Goods station, later renamed Tunbridge Wells Central Goods station.[2][36] The goods station closed in 1980, with a siding retained for engineers use.[37] The original station was 44 miles 23 chains (44.29 mi; 71.27 km) from London Bridge via Redhill.[2][35][Note 4]

The building on the up side of the station was built in the Italianate style.[38] A new building by A. H. Blomfield was constructed on the down side in 1911. The station was renamed Tunbridge Wells Central on 9 July 1923 with the ex-LBSC station being renamed Tunbridge Wells West.[39][40] Following the closure of the Tunbridge Wells–Eridge railway on 6 July 1985,[41] the name reverted to Tunbridge Wells. The station is 34 miles 32 chains (34.40 mi; 55.36 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- Frant

Frant station is 36 miles 53 chains (36.66 mi; 59.00 km) from Charing Cross.[35] The station building is on the down side.[42]

- Wadhurst

Wadhurst station is 39 miles 23 chains (39.29 mi; 63.23 km) from Charing Cross.[35] The station building is in the Italianate style, with a later one-bay extension. The 1893-built signal box,[42] decommissioned on 20 April 1986,[43] was purchased by the Kent and East Sussex Railway.[44]

- Witherenden

Witherenden station is 43 miles 66 chains (43.83 mi; 70.53 km) from Charing Cross.[35] It was renamed Ticehurst Road in December 1851, and Stonegate on 16 June 1947.[45]

- Etchingham

Etchingham station is 47 miles 34 chains (47.43 mi; 76.32 km) from Charing Cross.[35] The building is on the up side.[46]

- Robertsbridge

Robertsbridge station is 49 miles 37 chains (49.46 mi; 79.60 km) from Charing Cross.[35] On 26 March 1900, it became a junction with the opening of the Rother Valley Railway to freight. The line opened to passengers on 2 April 1900,[47] and was renamed the Kent and East Sussex Railway in 1904. [48] The Kent and East Sussex Railway closed to passengers on 2 January 1954 and to freight on 12 June 1962,[49] except for a short section serving a mill at Robertsbridge which closed on 1 January 1970.[50]

- Mountfield Halt

Mountfield Halt opened in 1923. It closed on 6 October 1969.[51] The platforms were built of sleepers and were demolished in the early 1970s.[52] The station was 53 miles 37 chains (53.46 mi; 86.04 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- Battle

Battle station opened on 1 September 1851.[12] The buildings are in the Gothic style and stand on the up side.[52] The station is 55 miles 46 chains (55.58 mi; 89.44 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- Crowhurst

A siding had existed at Crowhurst from 1877.[53] The station opened on 1 June 1902 and was located at the junction for the Bexhill West branch line, which also opened the same day.[54] Despite the line's closure on 14 June 1964, Crowhurst station remains open.[55] The station is 57 miles 45 chains (57.56 mi; 92.64 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- West St Leonards

West St Leonards station opened on 1 October 1887.[56] The buildings are wood framed and covered with weatherboards.[57] The station is 60 miles 59 chains (60.74 mi; 97.75 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- St Leonards Warrior Square

St Leonards Warrior Square station opened on 13 February 1851[58] along with a new section of line between Hastings and the LBSCs Hastings & St Leonards station. This gave the LBSC better access to Hastings.[10][59] It lies between Bopeep Tunnel and Hastings Tunnel.[60] The station is 61 miles 55 chains (61.69 mi; 99.28 km) from Charing Cross.[35]

- Hastings

Hastings station opened on 13 February 1851 along with the SER branch from Ashford.[59] Through platforms were provided for SER services and a separate terminal plaform for LBSC services.[61] The station was rebuilt and enlarged by the SER in 1880 as it was then inadequate for the increasing seasonal traffic. In 1930 the station was rebuilt by the Southern Railway. This entailed closure of the engine sheds at Hastings, with locomotives being transferred to St Leonards. The original station building, by Tress, was demolished and a new Neo-Georgian station building by J. R. Scott was erected. The rebuilt station was completed on 5 July 1931.[62] The new layout provided two island platforms.[63] The station was rebuilt in 2003 by Railtrack. The 1931-built building was demolished and a new structure erected in its place.[64] The station is 62 miles 33 chains (62.41 mi; 100.44 km) from Charing Cross via Orpington.[35]

Built

In the late 1860s, a single track link was built between the SERs Tunbridge Wells station and the LBSCs Tunbridge Wells station, which had opened in 1866. It was 1875 before powers were granted to run a passenger service over this section of line.[65] The junction with the main line was Grove Junction. It was removed on 7 July 1985, following closure of the Tunbridge Wells Central–Eridge line the previous day.[41]

In 1900, the Rother Valley Railway opened from Robertsbridge to Tenterden. It was extended in stages to Tenterden Town and Headcorn, which was reached in 1905.[66] The line closed to passengers on 2 January 1954 and freight on 12 June 1961, except for access to Hodson's Mill closed in 1970.[49] The Rother Valley Railway heritage railway are rebuilding the line between Robertsbridge and Junction Road, with completion scheduled by 2018.[67] In 1902, a branch line was built to Bexhill West, with a new station at the junction with the main line at Crowhurst.[54] This line closed on 14 June 1964.[55]

Authorised

In 1903, a railway was authorised to be built from Robertsbridge to Pevensey, East Sussex. The line was authorised under the Light Railways Act 1896,[68] but was not constructed.[69]

Proposed

In 1856, it was proposed to build a 6-mile (9.66 km) long branch from Witherenden to Mayfield, East Sussex.[70][Note 5] In 1882, an 18-mile-40-chain (18.50 mi; 29.77 km) long railway was proposed from Ticehurst Road to Langney, East Sussex, giving access to Eastbourne. Stations were proposed at Burwash, Dallington, Bodle Street Green, Boreham Street, Pevensey and Langney.[71]

Planned electrification

Electrification of the Hastings line was first considered by the SER as early as 1903. Lack of finance meant that no decision had been made by the time World War I broke out in 1914.[72] It was stated in 1921 that electrification was a long-term aim. In the mid-1930s, the Southern Railway, which had been formed from the SER, LBSC, London and South Western Railway (LSWR) and London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) in 1923 under the Railways Act 1921, electrified a number of lines. The East Coastway line was electrified in 1935, with a depot being built at Ore, East Sussex. In 1937, it was proposed to electrify the line between Sevenoaks and St Leonards Warrior Square at a cost of £1,500,000. The scheme was deferred, with another proposal in 1937 costing £1,300,000 also failing to gain favour before World War II broke out. One of the main reasons that electrification was not given the go-ahead was the fact that non-standard rolling stock would be required. The Southern Railway had provided the line with 104 new carriages and six Pullman Cars between 1929 and 1934.[22] Two electric locomotives were ordered in 1937. They were built to the Hastings line loading gauge.[73]

In October 1946, the Southern Railway announced a programme to electrify all lines in Kent and East Sussex in three stages. The Hastings line between Tonbridge and Bopeep Junction was to be part of the third stage.[73] Track would have been slewed within the affected tunnels with only one train normally allowed in the tunnel. In an emergency, two trains would be allowed in the tunnel at the same time, but restricted to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). Standard 9 feet 0 inches (2.74 m) wide stock would be used.[74] Following the nationalisation of railways in the United Kingdom under the Transport Act 1947, the Southern Region of British Railways shelved new electrification schemes, concentrating on the construction of new steam locomotives.[73] In 1952, the possibility of operating standard rolling stock on the line had been examined. The Operating Department objected to the use of single line sections through the various tunnels. The 1930s stock was refurbished with the aim of extending its service by a further ten years. The first two phases of the Southern Railway's electrification scheme were revived in 1955. This did not include the Hastings line and it was announced in 1956 that a fleet of diesel-electric trains would be constructed to operate the service until the line was electrified. At that time, the rolling stock built in the 1930s was overdue for replacement.[75] The modernisation to the Hastings line and the introduction of the diesel-electric trains cost £797,000, [74] of which £595,000 was the cost of the first seven trains.[76] A further thirteen trains cost £1,178,840.[77]

Electrification was finally carried out in the 1980s, as detailed below.

Operators

From 1845, the line was operated by the SER.[1] In 1899, the SER and LCDR entered into a joint working partnership, the South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SECR).[78] On 1 January 1923, the Railways Act 1921 came into force, resulting in the Grouping.[79] The SECR became part of the Southern Railway (SR).[80] On 1 January 1948, the Transport Act 1947 came into force,[81] and the SR became part of British Railways, with the former SR lines becoming the Southern Region.[82] British Railways was rebranded British Rail on 1 January 1965.[83] On 10 June 1986, Network SouthEast branded trains began operating.[84] On 1 January 1994, the Railways Act 1993 came into force, privatising British Rail. Passenger services were taken over by Connex South Eastern on 13 October 1996. On 27 June 2003, Connex lost the franchise due to poor financial management.[85] The Strategic Rail Authority took over the running of passenger trains from 9 November 2003, using their South Eastern Trains train operating company.[86] On 1 April 2006, Southeastern took over the operation of passenger trains on the route.[87] On 17 October 2021 SE Trains took over the operation of passenger trains on the route.[88]

Operation

Steam era (1845–1957)

From the opening of the line, passenger stock consisted of 4-wheel carriages.[89] In 1845, there were eight passenger trains a day from Tunbridge Wells to London, with half that number on Sundays.[90] On 23 June 1849, the Royal Train took Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to Tunbridge Wells to visit Queen Adelaide, the Queen Dowager. The train, consisting of the Royal Saloon, two first class carriages and a brake van made the journey from Bricklayers Arms to Tunbridge Wells in 75 minutes. It was driven by James Cudworth, the Locomotive Superintendent of the SER. The return journey took 70 minutes.[91] The Royal Train visited the line again on 18 December 1849 conveying Queen Victoria and Princess Alice from Windsor, Berkshire to Tunbridge Wells on a visit to Princess Louise. The journey via Waterloo took 100 minutes. The train was driven by William Jacomb, Resident Engineer of the LSWR, and Edgar Verringer, Superintendent of the LSWR. At Waterloo, driving of the train was taken over by John Shaw, General Manager of the SER and Mr. Cockburn, Superintendent of the SER. The return journey took 105 minutes.[92]

With the opening of the extension to Robertsbridge, there were three trains a day, with two on Sundays. These were augmented by an additional train daily when the extension to Bopeep Junction opened. In 1860, there were seven up trains and six down trains daily; Hastings to London via Redhill taking two hours.[90] From 1861, Cudworth 2-2-2 "Little Mail" class locomotives were introduced.[93] In 1876, the Sub-Wealden Gypsum Co built a 1 mile (1.61 km) long line from a junction south of Mountfield Tunnel to a gypsum mine located in Great Wood, Mountfield.[94] This line was still in operation as of 2007.[95] Bogie carriages entered service on the line in 1880.[89] In 1890, the winter service was eleven trains each way, of which five were fast.[Note 6] An additional two trains daily operated between Tunbridge Wells and Wadhurst. By 1910, this had increased to twenty trains each way, of which twelve were fast, plus the extra two Wadhurst services. Four trains ran on Sundays. The service was reduced during World War I, but Sunday services had increased to seven by 1922.[90]

By the 1930s the line was worked by L and L1 class 4-4-0 locomotives. The Schools class 4-4-0s were introduced in 1930;[96] the width of these was 8 feet 4 inches (2.54 m) measured across the cab, and 8 feet 6+1⁄2 inches (2.604 m) measured across the cylinders.[97] The service was again reduced during World War II, with fourteen trains daily in 1942, of which four were fast; there were seven trains on Sundays.[90] As built, it was envisaged that the West Country and Battle of Britain class locomotives would be able to work the line. Forty-eight locomotives of the West Country and 22 of the Battle of Britain class were built with cabs that were 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) wide and paired with tenders of the same width. It was subsequently decided not to work these locomotives over the line.[98][99] Locomotives from these two classes that were rebuilt gained a 9-foot-0-inch-wide (2.74 m) cab. Unrebuilt locomotives retained their narrow cab.[100]

By 1948, the service was sixteen trains, of which seven were fast. An additional three trains ran as far as Wadhurst. In 1957, the service was eighteen trains daily, of which nine were fast. There were nine trains on Sundays. The Schools Class locomotives worked the line until 1957 when steam was withdrawn on the Hastings line. Diesel-electric multiple units of what became British Rail Class 201, 202 and 203 (the "Hastings Diesels") took over working the route.[90]

Under British Railways, classes D1, E1, H, N1, M7, Q, Q1, Std 3 2-6-2T, Std 4 2-6-0 Std 4 2-6-4T and U1 were permitted to work between Tonbridge and Grove junction. Freight trains from Tonbridge West Yard were not permitted to depart until the line was clear as far as Southborough Viaduct.[101] Other classes of locomotive known to have worked over this section of line include C,[102] and E4.[103]

Diesel-electric era (1957–86)

.jpg.webp)

Special narrow bodied diesel electric multiple units were introduced in 1957–58 to replace steam traction. British Rail Class 201 (6S), 202 (6L) and 203 (6B) (the "Hastings Diesels") took over working the route. These units were constructed of narrow rolling stock. They were delivered in six-car formations (the 6Bs including a buffet car) and two units were often operated in multiple to form twelve-car trains.[90] In latter years some of the units were reduced to five,[104] and later still, to four cars.[105]

The 6S units were intended to be introduced into service in June 1957. On 5 April a fire at Cannon Street signal box disabled all signalling equipment there. As a result, locomotive-hauled trains were banned from the station. A temporary signal box was commissioned on 5 May and the 6S units were introduced on peak services the next day. Two units coupled together formed the 06:58 and 07:26 Hastings–Cannon Street services in the morning, and the 17:18 and 18:03 Cannon Street–Hastings services in the evening. From 17 June the 6S and 6L units were working services throughout the day. The 6B units entered service between May and August 1958.[106]

The Hastings Diesels had almost completely replaced steam by June 1958.[107] With the introduction of the Hastings Diesels, an hourly service was provided. This split at Tunbridge Wells, with the front portion running fast to Crowhurst and the rear portion stopping at all stations. The service ran every two hours on Sundays.[90] The Hastings Diesels also worked services on the Bexhill West branch line until closure on 14 June 1964.[55] On 22 December 1958, 6L unit 1017 collided with 6B unit 1035 at Tunbridge Wells Central.[108][109]

In 1962, twelve Class 33/2 diesel locomotives, were also built with narrow bodies for the Hastings line. These enabled the last steam workings, overnight newspaper trains, to be withdrawn from the Hastings line.[110] Nineteen British Rail Class 207 (3D) diesel electric multiple units were built in 1962.[110] They operated over the Tonbridge–Grove Junction section of the line as part of a Tonbridge–Eastbourne (later Tonbridge–Eridge) service.[111][112] In 1963, Frant, Stonegate, Wadhurst and Mountfield Halt were proposed to be closed under the Beeching Axe.[113] One special working took place on 3 April 1966 when one of the ex-Great Western Railway diesel railcars, W20W, was worked between Tonbridge and Robertsbridge as an out of gauge load. The railcar had been purchased by the Kent and East Sussex Railway for £415 including delivery to Robertsbridge. After trying to "wriggle out" of the deal, British Rail eventually found a solution. The vehicle was ballasted so that it leant away from the tunnel walls by some 3 inches (80 mm) and was worked to Robertsbridge at a maximum of 20 miles per hour (32 km/h).[114] From 1977, there were two trains an hour, one fast and one slow. In May 1980,[90] the buffet cars were withdrawn from the 6B units, which were recoded as 5L, but retaining the Class 203 designation.[104] The fast trains were withdrawn in January 1981, with trains now stopping at all stations.[90]

Electric era (since 1986)

On 28 October 1983, it was announced that the Hastings line was to be electrified. Reasons that decided the issue included a commitment by British Rail to eliminate asbestos from all stock in service by 1988 and the increasing cost of maintaining the then ageing Hastings Diesels. The scheme was to cost £23,925,000. Electrification was finally completed in 1986, the line was electrified using 750 V DC third rail using standard rolling stock, and the expedient of singling the track through the narrow tunnels. The tunnels either side of Tunbridge Wells Central station were not singled because the fact that the south portal of Wells Tunnel and north portal of Grove Hill Tunnel were at the ends of the platforms meant it was impossible to install pointwork without reducing the length of platform available. A speed restriction was imposed through Wells Tunnel. Parliamentary powers were sought in 1979 to bore a second Grove Hill Tunnel, but there was much opposition from local residents. This, and the high cost, caused the proposal to be abandoned. The track in Grove Hill Tunnel was relaid on a concrete base, allowing alignment to be precisely controlled.[115]

The line was declared to conform to the standard C1 loading gauge on 14 March. The first passenger carrying train comprising C1 stock to use the line was a railtour on 15 March hauled by 50 025 Invincible. It was organised by the Southern Electric Group and ran from Paddington to Folkestone Harbour. A preview service of electric trains ran on 27 April 1986 and the full timetabled service commenced on 12 May 1986.[43] The next day, a wrong-side failure occurred involving three signals between Tonbridge and Hastings. Contractors had made errors in the wiring of the signal heads.[116] With the inauguration of electric services, a half-hourly service was operated, with trains departing from Charing Cross at 15 and 45 minutes past the hour. Those departing at xx:15 called at Waterloo East, Sevenoaks, Tonbridge, High Brooms, Tunbridge Wells, Wadhurst, Battle, St Leonards Warrior Square and Hastings, taking 84 minutes. Those departing at xx:45 called at Waterloo East, London Bridge, Orpington, Sevenoaks, Hildenborough, Tonbridge and then all stations to Hastings, taking 99 minutes.[117] The Royal Train visited the line on 6 May, conveying Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. It was stabled at Wadhurst whilst she ate lunch. The train was hauled by a Class 73 diesel-electric locomotive.[118] Upon electrification, services were operated by 4CEP,[31] 4CIG and 4VEP electric multiple units.[119]

Class 508 electric multiple units also operated services on the line from the Redhill direction as far as Tunbridge Wells.[120] When these units were withdrawn in the mid-2000s, they were replaced by Class 375 Electrostar,[121] Class 465 Networker and Class 466 Networker units.[122]

Train services on the line are provided by SE Trains, and are mostly operated by Class 375 Electrostar,[121] or occasionally Class 465/466 Networker units.[122] The line still sees a freight service to and from British Gypsum's sidings at Mountfield.[95] The line retains all its original intermediate station buildings, and is considered a well-preserved example of a Victorian secondary rail route.[123]

Accidents and incidents

A number of accidents have occurred on the Hastings line, none of which have involved the death of a passenger.

- On 4 October 1852, a passenger train was derailed between Ticehurst Road and Etchingham when the formation was flooded and washed away. Both engine crew members were injured.[124]

- On 21 June 1856, a passenger train derailed between Tunbridge Wells and Tunbridge Junction, killing the driver and injuring the fireman and a passenger.[125]

- On 25 October 1859, almost 250 yards (230 m) of track was washed away between St Leonards and Bexhill, affecting the Hastings line.[126]

- On 23 June 1861, a collision between SER and LBSC passenger trains occurred at Bo Peep Junction, injuring around ten people. The SER train had overran signals due to excessive speed, insufficient brakes, low rail adhesion or a combination of these factors.[127]

- On 30 September 1866, the slip portion of a train, which was to be worked forwards to Hastings, failed to stop at Tunbridge due to an error by the slip guard. It crashed into a rake of empty carriages 262 yards (240 m) east of the station. Eleven of the 40 passengers were injured.[128]

- On 22 February 1892, a SER locomotive was run into by a LBSC passenger train at Hastings. The passenger train had overrun a danger signal. Both locomotives were damaged.[129]

- On 29 August 1896, the locomotive of a Charing Cross to Hastings train was derailed near Etchingham when it collided with a traction engine and threshing machine using an occupation crossing.[130]

- On 29 April 1912, SECR F1 class locomotive No. 216 was working an empty stock train when it suffered the failure of the firebox crown near Tunbridge Wells due to a lack of water in the boiler. Both engine crew were severely injured by escaping steam and jumping from the moving locomotive.[131]

- On 6 January 1930, the rear carriages of a passenger train from Hastings to London were partially buried by a landslip near Wadhurst tunnel. The train was divided and the front part continued on to Tunbridge Wells, where it arrived 100 minutes late.[132]

- On 23 December 1958, 6L unit 1017 collided with 6B unit 1035 at Tunbridge Wells Central. Eighteen people were injured, with three of them admitted to hospital.[108][109]

- On 8 November 2010, a passenger train operated by Class 375 unit 375 711 failed to stop at Stonegate station due to maintenance errors in respect of the train's sanding apparatus. The train overran the station by 2 miles 36 chains (2.45 mi; 3.94 km). Following the incident, Southeastern reduced the interval that the sand hoppers were to be refilled from seven days to five days.[133] The company was fined £65,000 and ordered to pay £22,589 in costs.[134]

- On 23 December 2013, a landslip at Wadhurst was the first in a series of landslips up to February 2014 which led the line between Wadhurst and St. Leonards Warrior Square being closed and reopened three times, with speed restrictions in place following repairs. The train service was replaced by buses during closures.[135][136][137][138][139] Southeastern was criticised by Hastings and Rye MP Amber Rudd over poor customer service during this period.[140] By 12 March, the section between Wadhurst and Robertsbridge had reopened,[141] with full service being restored on 31 March.[142]

Notes

- ^ Information for this route-map of the Hastings line was compiled from various sources.[143][144][145]

- ^ The modern spelling of "Tonbridge" was not adopted as the official spelling until 1870.[146]

- ^ A gradient of 1 in 47 means that the line climbs (or descends) by 1 foot in 47 feet, or 1 metre in 47 metres horizontal distance.

- ^ This was the route of the line during the time that Tunbridge Wells Central Goods served as a passenger station. The line between Tunbridge and Orpington did not open until 1 May 1868.[147]

- ^ Mayfield was reached by railway in 1880, with the opening of the Cuckoo Line.[148]

- ^ Trains designated as "fast" did not call at every station. "Slow" trains called at all stations.

Footnotes

- Beecroft 1986, p. 7.

- "Tunbridge Wells Central Goods". Kentrail.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- HC Deb, 28 April 1845 vol 79 cc1369–70 Hansard website

- HC Deb, 5 May 1845 vol 80 c158 Hansard website

- HL Deb, 8 July 1845 vol 82 cc1130–31 Hansard website

- HC Deb, 14 July 1845 vol 82 c472 Hansard website

- HL Deb, 14 July 1845 vol 82 c430 Hansard website

- HL Deb, 22 July 1845 vol 82 cc870-71 Hansard website

- "Domestic News". The Standard. No. 3799. London. 2 August 1845. p. 5.

- "Hastings [page 1]". Kent Rail. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 91.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 8.

- "South Eastern Railway". Daily News. No. 3209. London. 29 August 1856.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 7.

- "Country News". The Illustrated London News. No. 239. London. 28 November 1846.

- Beecroft 1986, pp. 7–8.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Morning Chronicle. No. 26553. London. 2 February 1852.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Times. No. 20745. London. 10 March 1850. col D, p. 3.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Morning Chronicle. No. 26443. London. 15 September 1851.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Morning Chronicle. No. 26447. London. 19 September 1851.

- Jewell 1984, p. 11.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 10.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, The tunnels.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Standard. No. 12183. London. 28 August 1863.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 58.

- Moody 1979, p. 117.

- Jewell 1984, p. 2.

- Jewell 1984, p. 137.

- "Bo Peep". Campaign for Real Ale. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 134.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 73.

- Jewell 1984, pp. 107–08.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 1.

- Neve 1933, p. 126 (facing).

- "South Eastern & Chatham Railway Committee". Signalling Record Society. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 92.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 17.

- Jewell 1984, p. 95.

- "Tunbridge Wells Central". Kentrail.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 21.

- "Disused stations:Tunbridge Wells West". Disused-stations.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 107.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 74.

- "Northiam". Kentrail.org. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Butt 1995, pp. 229, 252.

- Jewell 1984, p. 111.

- Garrett 1987, p. 9.

- Garrett 1987, p. 12.

- Garrett 1987, p. 54.

- Rose 1984.

- Kidner 1985, p. 52.

- Jewell 1984, p. 124.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 91.

- Jewell 1984, p. 133.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 47.

- "Station opens". Hastings: Hastings Chronicle. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 136.

- Butt 1995, p. 204.

- Toynbee, Mark. "A Brief History of the Ashford–Hastings Line". Marsh Link Action Group. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 9.

- Mitchell & Smith 1986a, Illustration 109.

- "Hastings [page 2]". Kent Rail. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Mitchell & Smith 1986a, Illustration 114.

- "Hastings [page 4]". Kent Rail. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Jewell 1984, p. 98.

- Jewell 1984, p. 112.

- Courtney, Geoff. "RVR goes main line in 4½ million rebuilding project". Heritage Railway. Horncastle: Mortons Media Ltd (201): 20. ISSN 1466-3562.

- "Light Railways Act, 1896". The Times. No. 37287. London. 11 January 1904. col F, p. 14.

- Rose, Neil (Winter 1974). "The Robertsbridge & Pevensey Light Railway". The Tenterden Terrier. Tenterden: The Tenterden Railway Company Limited (5): 14–15.

- "Railway Intelligence". The Times. No. 22517. London. 5 November 1856. col E, p. 5.

- "Railway Extension in Sussex". The Times. No. 30641. London. 18 October 1882. col D, p. 4.

- Jewell 1984, p. 14.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 11.

- Robertson & Abbinnett 2012, p. 5.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 12.

- Robertson & Abbinnett 2012, p. 6.

- Robertson & Abbinnett 2012, p. 7.

- Nock 1961, pp. 124–26.

- Glover 2001, p. 15.

- Glover 2001, p. 24.

- Glover 2001, p. 68.

- Catt 1970, p. 18.

- Moody 1979, p. 162.

- "History of Network SouthEast". Michael Rodgers. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Train firm loses franchise". BBC News Online. 27 June 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Rail authority takes on franchise". BBC News Online. 8 November 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Rail firm announces more trains". BBC News Online. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Southeastern train services taken over by government". BBC News. 17 October 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- Jewell 1984, p. 12.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Passenger services.

- "Visit of Her Majesty and His Royal Highness Prince Albert to the Queen Dowager, at Tunbridge Wells". The Morning Chronicle. No. 24859. London. 25 June 1849.

- "Visit of the Queen to Dorden near Tunbridge Wells". The Morning Post. No. 32597. London. 19 December 1876.

- Jewell 1984, p. 21.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustrations 69-71.

- "GBRf route map". gbrailfreight.com. GBRf. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Jewell 1984, p. 16.

- Nock 1987, p. 161.

- Bradley 1976, pp. 61, 74, 78.

- Derry 2004, pp. 20–21.

- Bradley 1976, pp. 92–93.

- Sectional appendix 1960, pp. 133–34.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 27.

- Feaver 1992, p. 19.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 64.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 86.

- Beecroft 1986, pp. 38–40.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 40.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 55.

- "Driver's Escape in Train Crash". The Times. No. 54341. London. 23 December 1958. col D, p. 6.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 45.

- Beecroft 1986, p. 46.

- Mitchell & Smith 1986, Illustration 111.

- Beecroft 1986, Illustration 48.

- Judge 1986, pp. 197, 200.

- Beecroft 1986, pp. 66–69.

- Hidden 1989, p. 201.

- Glover 2001, p. 119.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Illustration 46.

- Glover 2001, pp. 118–19.

- robd8 (9 May 2008). "SouthEastern 508". Flickr. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Oast House Archive (26 June 2011). "Train out of High Brooms railway station". Geograph. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- N Chadwick (26 June 2011). "Train at Tunbridge Wells Station". Geograph. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Glasspool, David. "Wadhurst". Kent Rail. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Accident on the South-Eastern Railway". The Times. No. 21240. London. 7 October 1852. col C, p. 9.

- "Fatal Railway Accident". The Times. No. 22401. London. 23 June 1856. col B, p. 7.

- "Destructive Storm. Loss of the Royal Charter with 459 lives". The Bury and Norwich Post, and Suffolk Herald. No. 4036. Bury St. Edmunds. 1 November 1859.

- "South Eastern Railway" (PDF). Board of Trade. 22 July 1861. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- Board of Trade (10 October 1866). "South Eastern Railway" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Railway Accident at Hastings". The Times. No. 33568. London. 23 February 1892. col B, p. 10.

- "Traction Engines and Level Crossings". The Times. No. 34990. London. 8 September 1896. col B, p. 5.

- Board of Trade (12 October 1912). "South Eastern and Chatham Railway" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Landslip on Train". The Times. No. 45404. London. 7 January 1930. p. 14.

- "Station overrun at Stonegate, East Sussex" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. 8 November 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Southeastern fined £65,000 for 'out-of-control train'". BBC News Online. 6 July 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "London-Hastings rail passengers face more disruption after landslip". BBC News Online. 8 January 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Landslips in East Sussex disrupt Southeastern trains". BBC News Online. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Southeastern cuts trains after more East Sussex landslips". BBC News Online. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Flooding and landslips affect travel across the South East". BBC News Online. 10 February 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Closed railway line to reopen 'the last week of February'". Hastings: The Hastings & St. Leonards Observer. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Southeastern criticised after rail line reopening delay". BBC News Online. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Hastings line closed 'until further notice'". BBC News Online. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Hastings landslip line reopens after three months". BBC News Online. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Hurst 1988, p. 40.

- Jowett 1989, pp. 123, 127, 130, 132, 145.

- Yonge 2008, maps 10B, 18A, 18B, 18C.

- Chapman 1995, p. 6.

- Kidner 1977, p. 14.

- Mitchell & Smith 1986, Historical background.

References

- Beecroft, Geoffrey (1986). The Hastings Diesels Story. Chessington: Southern Electric Group. ISBN 0-906988-20-9. OCLC 17226439.

- Bradley, D. L. (September 1976). Locomotives of the Southern Railway, part 2. London: RCTS. ISBN 0-901115-31-2. OCLC 653065063.

- Butt, R. V. J. (October 1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199. OL 11956311M.

- Catt, A. R. (1970). The East Kent Railway. Lingfield: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-017-7. OCLC 6080810.

- Chapman, Frank (1995). Tales of Old Tonbridge. Brasted Chart: Froglets Publications Ltd. ISBN 1-872337-55-4. OCLC 41348297.

- Derry, Richard (2004). The Book of the West Country and Battle of Britain Pacifics. Clophill: Irwell Press. ISBN 1-903266-23-8. OCLC 655364246.

- Feaver, Mike (1992). Steam Scene at Tonbridge. Rainham: Meresborough Books. ISBN 0-948193-67-0. OCLC 57430473.

- Garrett, S. R. (March 1987). The Kent & East Sussex Railway (Revised ed.). Tarrant Hinton: The Oakwood Press. OCLC 548718.

- Glover, John (2001). Southern Electric. Hersham: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2807-9. OCLC 47193343.

- Hidden, Anthony (1989). Investigation into the Clapham Junction Railway Accident. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0-10-108202-9.

- Hurst, Geoffrey (1988). Miles and Chains. Vol. 5 Southern (Second ed.). Milton Keynes: Milepost Publications. p. 40. ISBN 0-947796-08-8.

- Jewell, Brian (1984). Down the line to Hastings. Southborough: The Baton Press. ISBN 0-85936-223-X. OCLC 51000953.

- Jowett, Alan (March 1989). Jowett's Railway Atlas of Great Britain and Ireland: From Pre-Grouping to the Present Day (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-086-0. OCLC 22311137.

- Judge, C. W. (1986). The History of the Great Western A.E.C. Diesel Railcars. Poole: The Oxford Publishing Co. ISBN 0-86093-139-0. OCLC 16684245.

- Kidner, R. W. (1977) [1963]. The South Eastern and Chatham Railway. Tarrant Hinton: The Oakwood Press. OCLC 58849403.

- Kidner, R. W. (1985). Southern Railway Halts. Survey and Gazetteer. Headington, Oxford: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-321-4. OCLC 15514757.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1986). Branch Lines to Tunbridge Wells from Oxted, Lewes and Polegate. Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-32-1. OCLC 60024130.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1986a). South Coast Railways - Eastbourne to Hastings. Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 0 906520 27 4. OCLC 4458766130.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1987). Tonbridge to Hastings. Easebourne: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-44-4.

- Moody, G. T. (1979) [1957]. Southern Electric 1909–1979 (Fifth ed.). Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 0-7110-0924-4.

- Neve, Arthur (1933). The Tonbridge of Yesterday. The Tonbridge Free Press. p. facing page 126. OCLC 20758037.

- Nock, O. S. (1961). The South Eastern and Chatham Railway. London: Ian Allan Ltd. OCLC 20792875.

- Nock, O. S. (1987). Great Locomotives of the Southern Railway. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates. ISBN 0-85059-735-8. OCLC 14128551. CN 5587.

- Rose, Neil (1984). Kent & East Sussex Railway Stockbook. Tenterden: Colonel Stephens Publications.

- Robertson, Kevin; Abbinnett, Hugh (2012). Southern Region DEMUs. Hersham: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd.

- "South Eastern & Chatham Railway Committee". Signalling Record Society. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Yonge, John (November 2008) [1994]. Jacobs, Gerald (ed.). Railway Track Diagrams 5: Southern & TfL (3rd ed.). Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. ISBN 978 0 9549866 4 3.

- Sectional Appendix to the Working Timetable and Books of Rules and Regulations. Waterloo Station: British Railways Southern Region, South Eastern Division. 1960.

External links

- Hastings & St Leonards: Railways and Stations, at 1066 online