Hausa language

Hausa (/ˈhaʊsə/;[4] Harshen/Halshen Hausa; Ajami: هَرْشَن هَوْسَ) is a Chadic language spoken by the Hausa people in Chad, and mainly within the northern half of Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Benin and the southern half of Niger, with significant minorities in Sudan and Ivory Coast.[5][6]

| Hausa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native to | Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Benin, and Ghana |

| Region | West Africa |

| Ethnicity | Hausa /Hausawa |

| Speakers | 50 million (native) (2019-2021)[1] 45 million (as a second language) (2019–2021)[2][3] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ha |

| ISO 639-2 | hau |

| ISO 639-3 | hau |

| Glottolog | haus1257 |

| Linguasphere | 19-HAA-b |

Areas of Niger and Nigeria where Hausa people are based. Hausa tribes are to the north. | |

Hausa is a member of the Afroasiatic language family[7] and is the most widely spoken language within the Chadic branch of that family. Ethnologue estimated that it was spoken as a first language by some 47 million people and as a second language by another 25 million, bringing the total number of Hausa speakers to an estimated 72 million.[8]

In Nigeria, the Hausa-speaking film industry is known as Kannywood.[9]

Classification

Hausa belongs to the West Chadic languages subgroup of the Chadic languages group, which in turn is part of the Afroasiatic language family.[10]

Geographic distribution

Native speakers of Hausa, the Hausa people, are mostly found in Southern Niger, and Northern Nigeria.[6][5][11] Furthermore, the language is used as a lingua franca by non-native speakers in most of Northern Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana and as a trade language across a much larger swathe of West Africa (Benin, Ghana, Cameroon, Togo, Chad and parts of Sudan).[5]

Dialects

Hausa presents a wide uniformity wherever it is spoken.[12] However, linguists have identified dialect areas with a cluster of features characteristic of each one.[13]

Traditional dialects

Eastern Hausa dialects include Dauranci in Daura, Kananci in Kano, Bausanci in Bauchi, Gudduranci in Katagum Misau and part of Borno, and Hadejanci in Hadejiya.[14]

Western Hausa dialects include Sakkwatanci in Sokoto, Katsinanci in Katsina, Arewanci in Gobir, Adar, Kebbi, and Zanhwaranci in Zamfara, and Kurhwayanci in Kurfey in Niger. Katsina is transitional between Eastern and Western dialects. Sokoto is used in a variety of classical Hausa literature, and is often known as Classical Hausa.[15]

Northern Hausa dialects include Arewa (meaning 'North') and Arewaci.

Zazzaganci in Zazzau is the major Southern dialect.[16]

The Daura (Dauranchi) and Kano (Kananci) dialect are the standard. The BBC, Deutsche Welle, Radio France Internationale and Voice of America offer Hausa services on their international news web sites using Dauranci and Kananci. In recent language development Zazzaganci took over the innovation of writing and speaking the current Hausa language use.[17]

Northernmost dialects and loss of tonality

The western to eastern Hausa dialects of Kurhwayanci, Damagaram and Adarawa, represent the traditional northernmost limit of native Hausa communities.[18] These are spoken in the northernmost sahel and mid-Saharan regions in west and central Niger in the Tillaberi, Tahoua, Dosso, Maradi, Agadez and Zinder regions.[18] While mutually comprehensible with other dialects (especially Sakkwatanci, and to a lesser extent Gaananci), the northernmost dialects have slight grammatical and lexical differences owing to frequent contact with the Zarma, Fula, and Tuareg groups and cultural changes owing to the geographical differences between the grassland and desert zones. These dialects also have the quality of bordering on non-tonal pitch accent dialects.

This link between non-tonality and geographic location is not limited to Hausa alone, but is exhibited in other northern dialects of neighbouring languages; example includes differences within the Songhay language (between the non-tonal northernmost dialects of Koyra Chiini in Timbuktu and Koyraboro Senni in Gao; and the tonal southern Zarma dialect, spoken from western Niger to northern Ghana), and within the Soninke language (between the non-tonal northernmost dialects of Imraguen and Nemadi spoken in east-central Mauritania; and the tonal southern dialects of Senegal, Mali and the Sahel).[19]

Ghanaian Hausa dialect

The Ghanaian Hausa dialect (Gaananci), spoken in Ghana and Togo, is a distinct western native Hausa dialect-bloc with adequate linguistic and media resources available. Separate smaller Hausa dialects are spoken by an unknown number of Hausa further west in parts of Burkina Faso, and in the Haoussa Foulane, Badji Haoussa, Guezou Haoussa, and Ansongo districts of northeastern Mali (where it is designated as a minority language by the Malian government), but there are very little linguistic resources and research done on these particular dialects at this time.

Gaananci forms a separate group from other Western Hausa dialects, as it now falls outside the contiguous Hausa-dominant area, and is usually identified by the use of c for ky, and j for gy. This is attributed to the fact that Ghana's Hausa population descend from Hausa-Fulani traders settled in the zongo districts of major trade-towns up and down the previous Asante, Gonja and Dagomba kingdoms stretching from the sahel to coastal regions, in particular the cities of Accra (Sabon Zango, Nima), Takoradi and Cape Coast

Gaananci exhibits noted inflected influences from Zarma, Gur, Jula-Bambara, Akan, and Soninke, as Ghana is the westernmost area in which the Hausa language is a major lingua-franca among sahelian/Muslim West Africans, including both Ghanaian and non-Ghanaian zango migrants primarily from the northern regions, or Mali and Burkina Faso. Ghana also marks the westernmost boundary in which the Hausa people inhabit in any considerable number. Immediately west and north of Ghana (in Cote d'Ivoire, and Burkina Faso), Hausa is abruptly replaced with Dioula–Bambara as the main sahelian/Muslim lingua-franca of what become predominantly Manding areas, and native Hausa-speakers plummet to a very small urban minority.

Because of this, and the presence of surrounding Akan, Gbe, Gur and Mande languages, Gaananci was historically isolated from the other Hausa dialects.[20] Despite this difference, grammatical similarities between Sakkwatanci and Ghanaian Hausa determine that the dialect, and the origin of the Ghanaian Hausa people themselves, are derived from the northwestern Hausa area surrounding Sokoto.[21]

Hausa is also widely spoken by non-native Gur, and Mandé Ghanaian Muslims, but differs from Gaananci, and rather has features consistent with non-native Hausa dialects.

Other native dialects

Hausa is also spoken in various parts of Cameroon and Chad, which combined the mixed dialects of Northern Nigeria and Niger. In addition, Arabic has had a great influence in the way Hausa is spoken by the native Hausa speakers in these areas.

Non-native Hausa

In West Africa, Hausa's use as a lingua franca has given rise to a non-native pronunciation that differs vastly from native pronunciation by way of key omissions of implosive and ejective consonants present in native Hausa dialects, such as ɗ, ɓ and kʼ/ƙ, which are pronounced by non-native speakers as d, b and k respectively. This creates confusion among non-native and native Hausa speakers, as non-native pronunciation does not distinguish words like daidai ("correct") and ɗaiɗai ("one-by-one"). Another difference between native and non-native Hausa is the omission of vowel length in words and change in the standard tone of native Hausa dialects (ranging from native Fulani and Tuareg Hausa-speakers omitting tone altogether, to Hausa speakers with Gur or Yoruba mother tongues using additional tonal structures similar to those used in their native languages). Use of masculine and feminine gender nouns and sentence structure are usually omitted or interchanged, and many native Hausa nouns and verbs are substituted with non-native terms from local languages.

Non-native speakers of Hausa numbered more than 25 million and, in some areas, live close to native Hausa. It has replaced many other languages especially in the north-central and north-eastern part of Nigeria and continues to gain popularity in other parts of Africa as a result of Hausa movies and music which spread out throughout the region.

Hausa-based pidgins

| Gibanawa | |

|---|---|

| Region | Jega, Nigeria |

Native speakers | None[22] |

Hausa-based pidgin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | gib |

| Glottolog | giba1240 |

| ELP | Gibanawa |

There are several pidgin forms of Hausa. Barikanchi was formerly used in the colonial army of Nigeria. Gibanawa is currently in widespread use in Jega in northwestern Nigeria, south of the native Hausa area.[23]

Phonology

Consonants

Hausa has between 23 and 25 consonant phonemes depending on the speaker.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Dorsal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| front | plain | round | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

implosive | ɓ | ɗ | |||||

| voiced | b | d | (d)ʒ | ɟ | ɡ | ɡʷ | ||

| tenuis | t | tʃ | c | k | kʷ | ʔ | ||

| ejective | (t)sʼ | (tʃʼ) | cʼ | kʼ | kʷʼ | |||

| Fricative | voiced | z | ||||||

| tenuis | ɸ | s | ʃ | h | ||||

| Approximant | l | j; j̰ | w | |||||

| Rhotic | r | ɽ | ||||||

The three-way contrast between palatalized velars /c ɟ cʼ/, plain velars /k ɡ kʼ/, and labialized velars /kʷ ɡʷ kʷʼ/ is found only before long and short /a/, e.g. /cʼaːɽa/ ('grass'), /kʼaːɽaː/ ('to increase'), /kʷʼaːɽaː/ ('shea-nuts'). Before front vowels, only palatalized and labialized velars occur, e.g. /ciːʃiː/ ('jealousy') vs. /kʷiːɓiː/ ('side of body'). Before rounded vowels, only labialized velars occur, e.g. /kʷoːɽaː/ ('ringworm').[24][25]

Glottalic consonants

Hausa has glottalic consonants (implosives and ejectives) at four or five places of articulation (depending on the dialect). They require movement of the glottis during pronunciation and have a staccato sound.

They are written with modified versions of Latin letters. They can also be denoted with an apostrophe, either before or after depending on the letter, as shown below.

- ɓ / b', an implosive consonant, [ɓ], sometimes [ʔb];

- ɗ / d', an implosive [ɗ], sometimes [dʔ];

- ts', an ejective consonant, [tsʼ] or [sʼ], according to the dialect;

- ch', an ejective [tʃʼ] (does not occur in Kano dialect)

- ƙ / k', an ejective [kʼ]; [kʲʼ] and [kʷʼ] are separate consonants;

- ƴ / 'y is a palatal approximant with creaky voice, [j̰],[26] found in only a small number of high-frequency words (e.g. /j̰áːj̰áː/ "children", /j̰áː/ "daughter"). Historically it developed from palatalized [ɗ].[27]

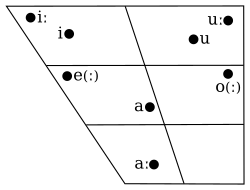

Vowels

Hausa vowels occur in five different vowel qualities, all of which can be short or long, totaling 10 monophthongs. In addition, there are four diphthongs, giving a total number of 14 vocalic phonemes.

- Monophthongs

- Short (single) vowels: /i, u, e, o, a/.

Long vowels: /iː, uː, eː, oː, aː/.

In comparison with the long vowels, the short /i, u/ can be similar in quality to the long vowels, mid-centralized to [ɪ, ʊ] or centralized to [ɨ, ʉ].[28]

Medial /i, u/ can be neutralized to [ɨ ~ ʉ], with the rounding depending on the environment.[29]

Medial /e, o/ are neutralized with /a/.[29]

The short /a/ can be either similar in quality to the long /aː/, or it can be as high as [ə], with possible intermediate pronunciations ([ɐ ~ ɜ]).[28]

- Diphthongs

- /ai, au, iu, ui/.

Tones

Hausa is a tonal language. Each of its five vowels may have low tone, high tone or falling tone. In standard written Hausa, tone is not marked. In recent linguistic and pedagogical materials, tone is marked by means of diacritics.

- à è ì ò ù – low tone: grave accent (`)

- â ê î ô û – falling tone: circumflex (ˆ)

An acute accent (´) may be used for high tone, but the usual practice is to leave high tone unmarked.

Morphology

Except for the Zaria and Bauchi dialects spoken south of Kano, Hausa distinguishes between masculine and feminine genders.[15]

Hausa, like the rest of the Chadic languages, is known for its complex, irregular pluralization of nouns. Noun plurals in Hausa are derived using a variety of morphological processes, such as suffixation, infixation, reduplication, or a combination of any of these processes. There are 20 plural classes proposed by Newman (2000).[30]

| Class | Affix | Singular (ex.) | Plural (ex.) | Gloss (ex.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a-a | sirdì | siràda | 'saddle' |

| 2 | a-e | gulbi | gulàbe | 'stream' |

| 3 | a-u | kurmì | kuràmu | 'grove' |

| 4 | -aCe | wuri | wuràre | 'place' |

| 5 | -ai | malàm | malàmai | 'teacher' |

| 6 | -anni | watà | wàtànni | 'moon' |

| 7 | -awa | talàkà | talakawa | 'commoner' |

| 8 | -aye | zomo | zomàye | 'hare' |

| 9 | -Ca | tabò | tabba | 'scar' |

| 10 | -Cai | tudù | tùddai | 'high ground' |

| 11 | -ce2 | ciwò | cìwàce-cìwàce | 'illness' |

| 12 | -Cuna | cikì | cikkunà | 'belly' |

| 13 | -e2 | camfì | càmfe-càmfe | 'superstition' |

| 14 | -i | tàurarò | tàuràri | 'star' |

| 15 | -oCi | tagà | tagogi | 'window' |

| 16 | -u | kujèra | kùjèru | 'chair' |

| 17 | u-a | cokàli | cokulà | 'spoon' |

| 18 | -uka | layò | layukà | 'lane' |

| 19 | -una | rìga | rigunà | 'grown' |

| 20 | X2 | àkàwu | àkàwu-àkàwu | 'clerk' |

Pronouns

Hausa marks tense differences by different sets of subject pronouns, sometimes with the pronoun combined with some additional particle. For this reason, a subject pronoun must accompany every verb in Hausa, regardless of whether the subject is known from previous context or is expressed by a noun subject.[31]

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | indef | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | plural | singular | plural | singular | plural | |||||

| m | f | m | f | |||||||

| perfect | naː | mun | kaː | kin | kun | jaː | taː | sun | an | |

| relative | na | mukà | ka | kikà | kukà | ja | ta | sukà | akà | |

| negative | bàn ... ba | bàmù ... ba | bàkà ... ba | bàkì ... ba | bàkù ... ba | bài ... ba | bàtà ... ba | bàsù ... ba | bà’à ... ba | |

| continuous | inàː | munàː | kanàː | kinàː | kunàː | janàː / ʃinàː | tanàː | sunàː | anàː | |

| relative | nakèː / nikèː | mukèː | kakèː | kikèː | kukèː | jakèː / ʃikèː | takèː | sukèː | akèː | |

| negative | baː nàː | baː màː | baː kàː | baː kjàː | baː kwàː | baː jàː | baː tàː | baː sàː | baː àː | |

| negative (possessives) |

bâː ni | bâː mu | bâː ka | bâː ki | bâː ku | bâː ʃi | bâː ta | bâː su | bâː a | |

| subjunctive | ìn | mù | kà | kì | kù | jà | tà | sù | à | |

| negative | kadà/kâr ìn | kadà/kâr mù | kadà/kâr kà | kadà/kâr kì | kadà/kâr kù | kadà/kâr jà | kadà/kâr tà | kadà/kâr sù | kadà/kâr à | |

| future | zân / zaː nì | zaː mù | zaː kà | zaː kì | zaː kù | zâi / zaː jà | zaː tà | zaː sù | zaː à | |

| negative | bà/bàː zân ... ba / bà/bàː zaː nì ... ba |

bà/bàː zaː mù ... ba | bà/bàː zaː kà ... ba | bà/bàː zaː kì ... ba | bà/bàː zaː kù ... ba | bà/bàː zâi ...ba / bà/bàː zaː jà ... ba |

bà/bàː zaː tà ... ba | bà/bàː zaː sù ... ba | bà/bàː zaː à ... ba | |

| indefinite future | nâː | mâː/mwâː | kâː | kjâː | kwâː | jâː | tâː | sâː/swâː | âː | |

| negative | bà nâː... ba | bà mâː/mwâː ... ba | bà kâː ... ba | bà kjâː ... ba | bà kwâː ... ba | bà jâː ... ba | bà tâː ... ba | bà sâː/swâː ... ba | bà âː ... ba | |

| habitual | nakàn | mukàn | kakàn | kikàn | kukàn | jakàn | takàn | sukàn | akàn | |

| negative | bà nakàn ... ba | bà mukàn ... ba | bà kakàn ... ba | bà kikàn ... ba | bà kukàn ... ba | bà jakàn ... ba | bà takàn ... ba | bà sukàn ... ba | bà akàn ... ba | |

Writing systems

Boko (Latin)

Hausa's modern official orthography is a Latin-based alphabet called boko, which was introduced in the 1930s by the British colonial administration.

| A a | B b | Ɓ ɓ | C c | D d | Ɗ ɗ | E e | F f | G g | H h | I i | J j | K k | Ƙ ƙ | L l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /b/ | /ɓ/ | /tʃ/ | /d/ | /ɗ/ | /e/ | /ɸ/ | /ɡ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /(d)ʒ/ | /k/ | /kʼ/ | /l/ |

| M m | N n | O o | R r | (R̃ r̃) | S s | Sh sh | T t | Ts ts | U u | W w | Y y | (Ƴ ƴ) | Z z | ʼ |

| /m/ | /n/ | /o/ | /ɽ/ | /r/ | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ | /(t)sʼ/ | /u/ | /w/ | /j/ | /ʔʲ/ | /z/ | /ʔ/ |

The letter ƴ (y with a right hook) is used only in Niger; in Nigeria it is written ʼy.

Tone and vowel length are not marked in writing. So, for example, /dàɡà/ "from" and /dáːɡáː/ "battle" are both written daga. The distinction between /r/ and /ɽ/ (which does not exist for all speakers) is not always marked.

Ajami (Arabic)

Hausa has also been written in ajami, an Arabic alphabet, since the early 17th century. The first known work to be written in Hausa is Riwayar Nabi Musa by Abdullahi Suka in the 17th century.[33] There is no standard system of using ajami, and different writers may use letters with different values. Short vowels are written regularly with the help of vowel marks, which are seldom used in Arabic texts other than the Quran. Many medieval Hausa manuscripts in ajami, similar to the Timbuktu Manuscripts, have been discovered recently; some of them even describe constellations and calendars.[34]

In the following table, short and long e are shown along with the Arabic letter for t (ت).

| Latin | IPA | Arabic ajami |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | ـَ |

| a | /aː/ | ـَا |

| b | /b/ | ب |

| ɓ | /ɓ/ | ب (same as b), ٻ (not used in Arabic) |

| c | /tʃ/ | ث |

| d | /d/ | د |

| ɗ | /ɗ/ | د (same as d), ط (also used for ts) |

| e | /e/ | تٜ (not used in Arabic) |

| e | /eː/ | تٰٜ (not used in Arabic) |

| f | /ɸ/ | ف |

| g | /ɡ/ | غ |

| h | /h/ | ه |

| i | /i/ | ـِ |

| i | /iː/ | ـِى |

| j | /(d)ʒ/ | ج |

| k | /k/ | ك |

| ƙ | /kʼ/ | ك (same as k), ق |

| l | /l/ | ل |

| m | /m/ | م |

| n | /n/ | ن |

| o | /o/ | ـُ (same as u) |

| o | /oː/ | ـُو (same as u) |

| r | /r/, /ɽ/ | ر |

| s | /s/ | س |

| sh | /ʃ/ | ش |

| t | /t/ | ت |

| ts | /(t)sʼ/ | ط (also used for ɗ), ڟ (not used in Arabic) |

| u | /u/ | ـُ (same as o) |

| u | /uː/ | ـُو (same as o) |

| w | /w/ | و |

| y | /j/ | ی |

| z | /z/ | ز ذ |

| ʼ | /ʔ/ | ع |

Other systems

Hausa is one of three indigenous languages of Nigeria which has been rendered in braille.

At least three other writing systems for Hausa have been proposed or "discovered". None of these are in active use beyond perhaps some individuals.

See also

- Hausa people

- History of Niger

- History of Nigeria

- Kanem Empire

- Bornu Empire

- Bayajidda

References

- Hausa at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Hausa language at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- Hausa language at Ethnologue (20th ed., 2017)

- Bauer (2007), p. ?.

- Wolff, H. Ekkehard. "Hausa language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- "Spread of the Hausa Language". Worldmapper. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- chayes. "The Hausa Language". Website des Institutes für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- "Hausa language". Ethnologue.

- "Nigerian actress Rahama Sadau banned after on-screen hug". BBC News. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- "Chadic languages | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- Sani, M. A. Z. (1999). Tsarin sauti da nahawun hausa. Ibadan [Nigeria]: University Press. ISBN 978-978-030-535-2. OCLC 48668741.

- Department, United States Army; Army, United States Department of the (1964). U.S. Army Area Handbook for Nigeria. Second Edition, March 1964. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- "Hausa Language Variation and Dialects". African Languages at UCLA. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- "The Hausa Language – Department of African Studies". www.iaaw.hu-berlin.de. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- Caron, Bernard (2011). Hausa Grammatical Sketch. Paris: LLACAN.

- "Nigeria: 'Tribalism' and the nationality question". Punch Newspapers. 2020-11-16. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- onnaedo (2021-08-31). "Hausa Language: 4 interesting things you should know about Nigeria's most widely spoken dialect". Pulse Nigeria. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- "Hausawa". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- "'THE IMPROTANCE OF HAUSA LANGUAGE AS A VERBAL COMMUNICATION TO HAUSA PEOPLE' AS THE RESEARCH TOPIC". Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- "Njas.helsinki.fi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-07. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- "Ethnorema.it" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-28. Retrieved 2021-07-17.

- Gibanawa at Ethnologue (24th ed., 2021)

- Gibanawa at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- Schuh & Yalwa (1999), p. 91.

- Newman, Paul (1996). "Hausa Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S.; Daniels, Peter T. (eds.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa (PDF). Eisenbrauns. pp. 537–552.

- Hausa ejectives and laryngealized consonants. Sound files hosted by the University of California at Los Angeles, from: Ladefoged, Peter: A Course in Phonetics. 5th ed. Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Newman, Paul (1937/2000) The Hausa Language: an encyclopedic reference grammar. Yale University Press. p. 397.

- Schuh & Yalwa (1999), pp. 90–91.

- Schuh & Yalwa (1999), p. 90.

- Guzmán Naranjo, Matías; Becker, Laura (April 2017). Quantitative methods in African Linguistics - Predicting plurals in Hausa (PDF). ACAL 48. Indiana, U.S.

- Hausa Verb Tense - African Languages at UCLA

- Bernard Caron. Hausa Grammatical Sketch. 2015. Hausa Grammatical Sketch - HAL-SHS

- "Hausa language | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- Verde, Tom (October 2011). "From Africa, in Ajami". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 2014-11-30. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- "Hausa alphabet"

- "Hausa alphabet from a 1993 publication". www.bisharat.net. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- "Hausa alphabet from a 1993 publication". www.bisharat.net. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

Bibliography

- Philips, John Edward . “Hausa in the Twentieth Century: An Overview.” in Sudanic Africa, vol. 15, 2004, pp. 55–84. online, on Romanization of the language.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2758-5.

- Schuh, Russell G.; Yalwa, Lawan D. (1999). "Hausa". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–95. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- Charles Henry Robinson; William Henry Brooks; Hausa Association, London (1899). Dictionary of the Hausa Language: Hausa–English. The Oxford University Press.

- Schön, James Frederick (Rev.) (1882). Grammar of the Hausa language. archive.org. London: Church Missionary House. p. 270. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved Oct 19, 2018. (Now in the public domain).

External links

- Hausa language at Curlie

- Omniglot

- Hausa Language Acquisitions at Columbia University Libraries

- Hausa Vocabulary List –World Loanword Database

- Hausa Dictionary at University of Vienna

- Hausar Yau Da Kullum: –Intermediate and Advanced Lessons in Hausa Language and Culture

- Hausa News and Blog at the University of Ahmadu bello university also visit www.dariyamedia.com for more info about hausa culture and people