Hegra (Mada'in Salih)

Hegra (Ancient Greek: Ἕγρα),[1][2] known to Muslims as Al-Hijr (Arabic: ٱلْحِجْر),[3] also known as Mada’in Salih[4] (Arabic: مَدَائِن صَالِح, romanized: madāʼin Ṣāliḥ, lit. 'Cities of Salih'), is an archaeological site located in the area of Al-'Ula within Medina Province in the Hejaz, Saudi Arabia. A majority of the remains date from the Nabataean Kingdom (1st century AD). The site constitutes the kingdom's southernmost and second largest city after Petra (now in Jordan), its capital city.[5] Traces of Lihyanite and Roman occupation before and after the Nabatean rule, respectively, can also be found.

.jpg.webp) Al-Hijr or Mada'in Salih | |

Shown within Saudi Arabia | |

| Alternative name | Al-Hijr ٱلْحِجْر Mada’in Salih |

|---|---|

| Location | Al Madinah Region, Al-Hejaz, Saudi Arabia |

| Coordinates | 26°47′30″N 37°57′10″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Official name | Hegra Archaeological Site (Al-Hijr / Madâ’in Sâlih) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii |

| Designated | 2008 (32nd session) |

| Reference no. | 1293 |

| Region | Arab states |

The Quran[6][7][3][8][9][10][11] places the settlement of the area by the Thamudi people during the days of Salih, between those of Nuh (Noah) and Hud on one hand, and those of Ibrahim (Abraham) and Musa (Moses) on the other. However, a definitive historical chronology can not be obtained through the order of verses due to the fact that the Quranic chapters (see surah) deal with different subjects in non-chronologic order.[12] According to the Islamic text, the Thamudis were punished by God for their idolatry, struck by an earthquake and lightning blasts. Thus, the site has earned a reputation as a cursed place—an image which the national government is attempting to overcome as it seeks to develop Mada'in Salih for its potential for tourism.[13]

In 2008, UNESCO proclaimed Mada'in Salih as a site of patrimony, becoming Saudi Arabia's first World Heritage Site. It was chosen for its well-preserved remains from late antiquity, especially the 131 monumental rock-cut tombs, with their elaborately ornamented façades, of the Nabataean Kingdom.[14]

Name

Its long history and the multitude of cultures occupying the site have produced several names. References by Strabo and other Mediterranean writers use the name Hegra (Ancient Greek: Ἔγρα) for the Nabatean site.[15][16][17] The use of Mada'in Salih refers to the Islamic Nabi (Prophet) Salih. The name Al-Hijr ("The Stoneland" or "The Rocky Place"),[3] has also been used to allude to its topography.[18]

Location

The archaeological site of Hegra is situated 20 km (12 mi) north of the town of Al-'Ula,[19] 400 km (250 mi) north-west of Medina, and 500 km (310 mi) south-east of Petra, Jordan. Al-Istakhri wrote in "Al-Masalik":

Al-Hijr is a small village. It belongs to Wadi al Gura and is located at one day's travel inside the mountains. It was the homeland of the Thamudians. I have seen those mountains and their carvings. Their houses are similar to ours but are carved in the mountains, which are called the Ithlib mountains. It looks as if they are a continuous range but they are separated and have sand dunes around them. You can reach the top of the mountains, but this is extremely tiring. The well of the Thamudians which is mentioned in the Holy Quran is located in the middle of the mountains.

— Al-Istakhri.[20]

The site is on a plain, at the foot of a basalt plateau, which forms a portion of the Hijaz mountains. Beneath the western and north-western parts of the site, the water table can be reached at a depth of 20 metres (66 ft).[18] The setting is notable for its desert landscape, marked by sandstone outcroppings of various sizes and heights.

History

In the Qur'an

According to Islamic tradition the site of Al-Hijr was settled by the tribe of Thamud,[22] who "(took) for (themselves) palaces from its plains and (carved) from the mountains, homes".[Quran 7:73-79][Quran 11:61-69][Quran 15:80-84] The tribe fell to idol worship, and oppression became prevalent.[23] Salih,[6][7][8][9][10][11] to whom the site's name of "Mada'in Salih" is often attributed,[24] called on the Thamudis to repent.[23] The Thamudis disregarded the warning and instead commanded Salih to summon a pregnant she-camel from the back of a mountain. And so a pregnant she-camel was sent to the people from the back of the mountain, as proof of Salih's divine mission.[23][25] However, only a minority heeded his words. The non-believers killed the sacred camel instead of caring for it as they were told, and its calf ran back to the mountain from whence it came. The Thamudis were given three days before their punishment was to take place, since they disbelieved and did not heed the warning. Salih and his Monotheistic followers left the city, but the others were punished by God—their souls leaving their lifeless bodies in the midst of an earthquake and lightning blasts.[23]

According to the Qur'an and tradition, the Thamud existed much earlier than the 715BC inscription from Sargon II would suggest.[26] However, recent research in Islamic studies asserts that a definitive chronology of the Thamūd cannot be attained from the Quranic context and that this narrative does not "depict a continuous history of the ancient people, because these are not in any genealogical succession, nor do they interact with one another."[27] Robert Hoyland suggested that their name was subsequently adopted by other new groups that inhabited the region of Mada'in Salih after the disappearance of the original people of Thamud.[28] This suggestion is also supported by the narration of ʿAbdullah ibn ʿUmar and analysis of Ibn Kathir which report that people called the region of Thamud Al-Hijr, while they called the province of Mada'in Salih as Ardh Thamud (Land of Thamud) and Bayt Thamud (house of Thamud).[29][30] So the term ‘Thamud’ was not applied to the groups that lived in Mada'in Salih, such as Lihyanites and Nabataeans,[31][32] but rather to the region itself, and according to classical sources, it was agreed upon that the only remaining group of the native people of Thamud are the tribe of Banu Thaqif which inhabited the city of Taif south of Mecca.[33][34][35]

Rock writings

Recent archaeological work has revealed numerous rock writings and pictures not only on Mount Athleb, but also throughout central Arabia.[36] They date between the sixth century BC and the fourth century AD and are labelled as being Thamudic. "Thamudic" was the name invented by nineteenth-century scholars for these large numbers of inscriptions which had not yet been properly studied.[37]

Lihyan/Dedanite era

Archaeological traces of cave art on the sandstones and epigraphic inscriptions, considered by experts to be Lihyanite script, on top of the Athleb Mountain,[22] near Hegra (Mada’in Salih), have been dated to the 3rd–2nd century BC,[18] indicating the early human settlement of the area, which has an accessible source of freshwater and fertile soil.[22][24] The settlement of the Lihyans became a center of commerce, with goods from the east, north and south converging in the locality.[22]

Nabatean era

The extensive settlement of the site took place during the 1st century AD,[38] when it came under the rule of the Nabatean king Aretas IV Philopatris (Al-Harith IV) (9 BC – 40 AD), who made Hegra (Mada’in Salih) the kingdom's second capital, after Petra in the north.[22] The place enjoyed a huge urbanization movement, turning it into a city.[22] Characteristic of Nabatean rock-cut architecture, the geology of Hegra (Mada’in Salih) provided the perfect medium for the carving of monumental structures, with Nabatean scripts inscribed on their façades.[18] The Nabateans also developed oasis agriculture[18]—digging wells and rainwater tanks in the rock and carving places of worship in the sandstone outcroppings.[24] Similar structures were featured in other Nabatean settlements, ranging from southern Syria (region) to the north, going south to the Negev, and down to the immediate area of the Hejaz.[18] The most prominent and the largest of these is Petra.[18]

At the crossroad of commerce, the Nabatean kingdom flourished, holding a monopoly for the trade of incense, myrrh and spices.[39] Situated on the overland caravan route and connected to the Red Sea port of Egra Kome,[18] Hegra, as it was known among the Nabateans, reached its peak as the major staging post on the main north–south trade route.[24]

Roman era

In 106 AD, the Nabatean kingdom was annexed by the contemporary Roman Empire.[39][40] The Hejaz, which encompasses Hegra, became part of the Roman province of Arabia.[18]

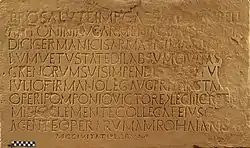

The Hedjaz region was integrated into the Roman province of Arabia in 106 AD. A monumental Roman epigraph of 175–177 AD was recently discovered at al-Hijr (then called "Hijr" and now Mada'in Salih).[18]

The trading itinerary shifted from the overland north–south axis on the Arabian Peninsula to the maritime route through the Red Sea.[24] Thus, Hegra as a center of trade began to decline, leading to its abandonment.[40] Supported by the lack of later developments based on archaeological studies, experts have hypothesized that the site had lost all of its urban functions beginning in the late Antiquity (mainly due to the process of desertification).[18] In the 1960s and 1970s, evidence was discovered that the Roman legions of Trajan occupied Mada'in Salih in northeastern Arabia, increasing the extension of the Arabia Petraea province of the Romans in Arabia.[41]

The history of Hegra, from the decline of the Roman Empire until the emergence of Islam, remains unknown.[40] It was only sporadically mentioned by travelers and pilgrims making their way to Mecca in the succeeding centuries.[24] Hegra served as a station along the Hajj route, providing supplies and water for pilgrims.[40] Among the accounts is a description made by 14th-century traveler Ibn Battuta, noting the red stone-cut tombs of Hegra, by then known as "al-Hijr."[18] However, he made no mention of human activities there.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman Empire annexed western Arabia from the Mamluks by 1517.[42] In early Ottoman accounts of the Hajj road between Damascus and Mecca, Hegra (Mada’in Salih) is not mentioned, until 1672, when the Turkish traveler, Evliya Celebi noted that the caravan passed through a place called "Abyar Salih" where there were the remains of seven cities.[43] It is again mentioned by the traveler Murtada ibn 'Alawan as a rest stop on the route called "al-Mada'in."[43] Between 1744 and 1757,[18][24] a fort was built at al-Hijr on the orders of the Ottoman governor of Damascus, As'ad Pasha al-Azm.[43] A cistern supplied by a large well within the fort was also built, and the site served as a one-day stop for Hajj pilgrims where they could purchase goods such as dates, lemons and oranges.[43] It was part of a series of fortifications built to protect the pilgrimage route to Mecca.[43]

According to the researches of Al-Ansari, the Ottoman castle was found near the settlement dating to the year 1600 A.D in 1984[20]

19th century

Following the discovery of Petra by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812, Charles Montagu Doughty, an English traveler, heard of a similar site near Hegra (Mada’in Salih), a fortified Ottoman town on the Hajj road from Damascus. In order to access the site, Doughty joined the Hajj caravan, and reached the site of the ruins in 1876, recording the visit in his journal which was published as Travels in Arabia Deserta.[24][40] Doughty described the Ottoman fort, where he resided for two months, and noted that Bedouin tribesmen had a permanent encampment just outside of the building.[43]

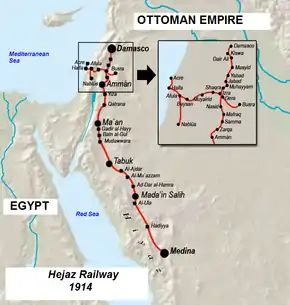

In the 19th century, there were accounts that the extant wells and oasis agriculture of al-Hijr were being periodically used by settlers from the nearby village of Tayma.[24][40] This continued until the 20th century, when the Hejaz Railway that passed through the site was constructed (1901–08) on the orders of Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II to link Damascus and Jerusalem in the north-west with Medina and Mecca,[24][40] hence facilitating the pilgrimage journey to the latter and to politically and economically consolidate the Ottoman administration of the centers of Islamic faith.[44] A station was built north of al-Hijr for the maintenance of locomotives, and offices and dormitories for railroad staff.[24] The railway provided greater accessibility to the site. However, this was destroyed in a local revolt during World War I.[45] Despite this, several archaeological investigations continued to be conducted in the site beginning in the World War I period to the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the 1930s up to the 1960s.[18][46] The railway station has also been restored and now includes 16 buildings and several pieces of rolling stock.[47]

By the end of the 1960s, the Saudi Arabian government devised a program to introduce a sedentary lifestyle to the nomadic Bedouin tribes inhabiting the area.[18] It was proposed that they settle down in al-Hijr, re-using the already existent wells and agricultural features of the site.[18] However, the official identification of al-Hijr as an archaeological site in 1972 led to the resettlement of the Bedouins towards the north, beyond the site boundary.[18] This also included the development of new agricultural land and freshly dug wells, thereby preserving the state of al-Hijr.

Current development

In 1962, examples of many inscriptions were discovered and renewed the archaeological assessment of Hijr (Mada’in Salih) by Winnett and Reed.[20] Although the Al-Hijr site was proclaimed as an archaeological treasure in the early 1970s, few investigations had been conducted since.[48] Mirdad had lived here for a short time and wrote notices about the region since 1977. Healey studied here in 1985 and wrote a book about the inscriptions of Hijr (Mada’in Salih) in 1993.[20]

The prohibition on the veneration of objects/artifacts has resulted in minimal archaeological activities. These conservative measures started to ease up beginning in 2000, when Saudi Arabia invited expeditions to carry out archaeological explorations as part of the government's push to promote cultural heritage protection and tourism.[48] The archaeological site was proclaimed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.[49] More recent archaeological studies of the area have been made as part of efforts to document and preserve the heritage sites prior to opening the area to more tourism.[50]

Architecture

The Nabatean site of Hegra was built around a residential zone and its oasis during the 1st century CE.[18] The sandstone outcroppings were carved to build the necropolis. A total of four necropolis sites have survived, which featured 131 monumental rock-cut tombs spread out over 13.4 km (8.3 mi),[51][52] many with inscribed Nabatean epigraphs on their façades:

| Necropolis | Location | Period of construction | Notable features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jabal al-Mahjar | North | no information | Tombs were cut on the eastern and western sides of four parallel rock outcrops. Façade decorations are small in size.[18] |

| Qasr al walad | no information | 0–58 AD | Includes 31 tombs decorated with fine inscriptions as well as artistic elements like birds, human faces and imaginary beings. Contains the most monumental of rock-cut tombs, including the largest façade measuring 16 m (52 ft) high.[18] |

| Area C | South-east | 16–61 AD | Consists of a single isolated outcrop containing 19 cut tombs.[53] No ornamentations were carved on the façades.[18] |

| Jabal al-Khuraymat | South-west | 7–73 AD | The largest of the four, consisting of numerous outcrops separated by sandy zones, although only eight of the outcrops have cut tombs, totaling 48 in quantity.[18] The poor quality of sandstone and exposure to prevailing winds resulted to the poor state of conservation of most façades.[53] |

Non-monumental burial sites, totaling 2,000, are also part of the place.[18] A closer observation of the façades indicates the social status of the buried person[24]—the size and ornamentation of the structure reflect the wealth of the person. Some façades had plates on top of the entrances providing information about the grave owners, the religious system, and the masons who carved them. Many graves indicate military ranks, leading archaeologists to speculate that the site might once have been a Nabatean military base, meant to protect the settlement's trading activities.[22]

The Nabatean kingdom was not just situated at the crossroad of trade but also of culture. This is reflected in the varying motifs of the façade decorations, borrowing stylistic elements from Assyria, Phoenicia, Egypt and Hellenistic Alexandria, combined with the native artistic style.[18] Roman decorations and Latin scripts also figured on the troglodytic tombs when the territory was annexed by the Roman Empire.[48] In contrast to the elaborate exteriors, the interiors of the rock-cut structures are severe and plain.

A religious area, known as "Jabal Ithlib," is located to the north-east of the site.[18] It is believed to have been originally dedicated to the Nabatean deity Dushara. A narrow corridor, 40 metres (131 ft) long between the high rocks and reminiscent of the Siq in Petra, leads to the hall of the Diwan, a Muslim's council-chamber or law-court.[18] Small religious sanctuaries bearing inscriptions were also cut into the rock in the vicinity.

The residential area is located in the middle of the plain, far from the outcrops.[18] The primary material of construction for the houses and the enclosing wall was sun-dried mudbrick.[18] Few vestiges of the residential area remain.

Water is supplied by 130 wells, situated in the western and north-western part of the site, where the water table was at a depth of only 20 m (66 ft).[18] The wells, with diameters ranging 4–7 m (13–23 ft), were cut into the rock, although some, dug in loose ground, had to be reinforced with sandstone.[18]

Importance

The archaeological site lies in an arid environment. The dry climate, the lack of resettlement after the site was abandoned, and the prevailing local beliefs about the locality have all led to the extraordinary state of preservation of Al-Hijr,[18] providing an extensive picture of the Nabatean lifestyle. Thought to mark the southern extent of the Nabatean kingdom,[54] Al-Hijr's oasis agriculture and extant wells exhibit the necessary adaptations made by the Nabateans in the given environment—its markedly distinct settlement is the second largest among the Nabatean kingdom, complementing that of the more famous Petra archaeological site in Jordan.[18] The location of the site at the crossroads of trade, as well as the various languages, scripts and artistic styles reflected in the façades of its monumental tombs further set it apart from other archaeological sites. It has duly earned the nickname "The Capital of Monuments" among Saudi Arabia's 4,000 archaeological sites.[48][24]

See also

- Iram of the Pillars

- Leuke Kome

- Lihyan

- Nabataeans

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

- Ancient towns in Saudi Arabia

- List of World Heritage Sites in Saudi Arabia

Footnotes

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §E260.11

- Strabo, Geography, § 16.4.24

- Quran 15:80–84 (Translated by Pickthall)

- "Hijr UNESCO World Heritage Site, Mada'in Salih | ExperienceAlUla.com". experiencealula.com. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Marjory Woodfield (21 April 2017). "Saudi Arabia's silent desert city". BBC News.

- Quran 7:73–79 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Quran 11:61–69 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Quran 26:141–158 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Quran 54:23–31 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Quran 89:6–13 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Quran 91:11–15 (Translated by Pickthall)

- Asad, M. "The Message of the Quran, 1982. [Note] Surah 17:2 briefly discusses Moses, followed by 17:3 dealing with Noah. Then Surah 17:59 deals with the Thamud, 17:61 deals with Adam's creation".

- Wood, Graeme (2022-03-03). "Absolute Power". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Madâin Sâlih)". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Harrison, Timothy P.. "Ḥijr." Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC. Brill Online, 2016.

- Strabo, Geography, 16.4.24

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, E260.11

- "ICOMOS Evaluation of Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Madâin Sâlih) World Heritage Nomination" (PDF). World Heritage Center. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- "AlUla the place of heritage for the world". experiencealula.com. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- "Mada'in Salih, a Nabataean town in north west Arabia: analysis and interpretation of the excavation 1986-1990".

- "HISTORY: Creation of Al-Hijr". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "HISTORY: Explanation of the Verses". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "HISTORY: Madain Salih". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- "Madain Salih – Cities inhabited by the People of Thamud". Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- M. Th. Houtsma et al., eds., E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936

- Angelika Neuwirth, Ali Aghaei, Tolou Khademalsharieh, Nicolai Sinai. "Corpus Coranicum: Sure 15: Egra (al-Ḥiǧr)".

[Transl.] What applies to the narrative sequence in Q:51 also applies to those in Q:15: Although the narratives (of Thamud) form a series together with the story of Noah and Pharaoh and establish a cross-temporal connection, they do not depict a continuous history of the ancient people, because these are not in any genealogical succession, nor do they interact with one another. [Original] Was für die Erzählsequenz in Q 51 gilt, trifft auch für die in Q 15 zu: Obwohl die Erzählungen zusammen mit der Geschichte von Noah und Pharao eine Serie bilden und einen zeitübergreifenden Zusammenhang herstellen, bilden sie doch keine kontinuierliche Geschichte der alten Völkerschaften ab, denn diese stehen untereinander in keiner genealogischen Sukzession, auch treten sie in keine Interaktion ein.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hoyland, Robert G. (2001). Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 0415195349.

- Sahih al-Bukhari, Narrated: ʿAbdullah ibn ʿUmar, Hadiths: 2116 & 3379

- Ibn Kathir (2003). Al-Bidâya wa-l-Nihâya ("The Beginning and the End") Vol.1. Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-Ilmiyya. p. 159.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. Page: 818

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Under the Category of: History of Arabia, the Section of: Dedān and Al-Ḥijr

- The Detailed History of Arabs before Islam, Prof. Jawwad Ali, Volume: 15, Page: 301

- The Historical Record of Ibn Khaldon, Volume: 2, Page: 641

- Kitab Al-Aghani, Abu Al-Faraj Al-Asfahani, Volume: 4, Page: 74

- "Thamūd". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. April 21, 2016.

- dan. "The Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia - Home". krc.orient.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. p. 818. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia Volume 8. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. p. 473. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- "HISTORY: Fall of Al-Hegra". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- Kesting, Piney. "Well of Good Fortune". Saudi Aramco World (May/June 2001). Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. p. 820. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- Petersen 2012, p. 146.

- Baker, Randall (1979). King Hussein And The Kingdom of Hejaz. p. 18. ISBN 0-900891-48-3.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia Volume 5. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. p. 809. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Macropædia Volume 13. USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1995. p. 840. ISBN 0-85229-605-3.

- "Move Under Way to Restore Madain Salih Railway Station". Arab News. 2006-06-22. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- Abu-Nasr, Donna (2009-08-30). "Digging up the Saudi past: Some would rather not". Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "Al-Hijr Archaeological Site (Madâin Sâlih)". UNESCO. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "Heritage Sites in AlUla, Saudi Arabia | ExperienceAlUla.com". experiencealula.com. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Information at nabataea.net". Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- "HISTORY: Al-Hijr". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "HISTORY: Tourist sites in Madain Salih". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- "HISTORY: Expansion of the Nabataeans". Historical Madain Salih. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

Further reading

- Abdul Rahman Ansary; Ḥusayn Abu Al-Ḥassān (2001). The civilization of two cities: Al-ʻUlā & Madāʼin Sāliḥ. Riyadh: Dar Al-Qawafil. ISBN 9960-9301-0-6. ISBN 978-9960-9301-0-7

- Mohammed Babelli (2003). Mada'in Salih. Riyadh: Desert Publisher. ISBN 978-603-00-2777-4. (I./2003, II./2005, III./2006, IV./2009.)

External links

- World Heritage listing submission

- Explore Hijr: the Archaeological Site of Al-Hijr (Mada'in Salih) in the UNESCO coleection on Google Arts and Culture

- ExperienceAlUla.com (Official Tourism Website)

- Photo gallery at nabataea.net

- Photos from Mauritian photographer Zubeyr Kureemun

- Historical Wonder by Mohammad Nowfal

- Saudi Arabia's Hidden City from France24

- Madain Salah: Saudi Arabia's Cursed City

- Uncovering secrets of mystery civilization in Saudi Arabia – BBC

- "Saudi Arabia’s Al Ula archaeologists unearth Gulf’s first domesticated dogs. The dig at Hegra uncovered remains of human beings and canines dating back 6,000 years. "The National News", March 25, 2021.

Videos

- The Road to Mada'in Salih

- Round in Mada'in Salih : Part1 – Part2 – Part3 – Part4