Helvetica

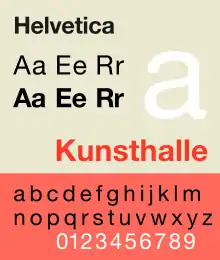

Helvetica (originally Neue Haas Grotesk) is a widely used sans-serif typeface developed in 1957 by Swiss typeface designer Max Miedinger and Eduard Hoffmann.

| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Neo-grotesque sans-serif[1] |

| Designer(s) | Max Miedinger, Eduard Hoffmann |

| Foundry | Haas Type Foundry |

| Date released | 1957 |

| Re-issuing foundries | Mergenthaler Linotype Company |

| Design based on | Akzidenz-Grotesk |

| Variations | Helvetica Inserat Helvetica Compressed Neue Helvetica Helvetica Now others (see below) |

| Also known as | Neue Haas Grotesk |

| Shown here | Neue Helvetica |

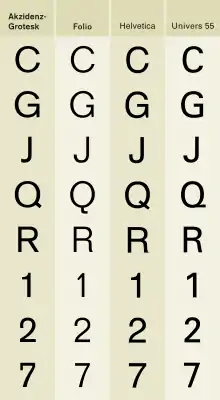

Helvetica is a neo-grotesque design, one influenced by the famous 19th century (1890s) typeface Akzidenz-Grotesk and other German and Swiss designs.[2] Its use became a hallmark of the International Typographic Style that emerged from the work of Swiss designers in the 1950s and '60s, becoming one of the most popular typefaces of the mid-20th century.[3] Over the years, a wide range of variants have been released in different weights, widths, and sizes, as well as matching designs for a range of non-Latin alphabets. Notable features of Helvetica as originally designed include a high x-height, the termination of strokes on horizontal or vertical lines and an unusually tight spacing between letters, which combine to give it a dense, solid appearance.

Developed by the Haas'sche Schriftgiesserei (Haas Type Foundry) of Münchenstein (Basel), Switzerland, its release was planned to match a trend: a resurgence of interest in turn-of-the-century "grotesque" sans-serifs among European graphic designers, that also saw the release of Univers by Adrian Frutiger the same year.[4][5][6] Hoffmann was the president of the Haas Type Foundry, while Miedinger was a freelance graphic designer who had formerly worked as a Haas salesman and designer.[7]

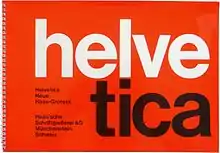

Miedinger and Hoffmann set out to create a neutral typeface that had great clarity, had no intrinsic meaning in its form, and could be used on a wide variety of signage.[7] Originally named Neue Haas Grotesk (New Haas Grotesque), it was rapidly licensed by Linotype and renamed Helvetica in 1960, which in Latin means "Swiss" (from Helvetia), capitalising on Switzerland's reputation as a centre of ultra-modern graphic design.[8] A feature-length film directed by Gary Hustwit was released in 2007 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the typeface's introduction in 1957.[9]

History

The first version of the typeface (which later became known as Helvetica) was created in 1957 by Swiss type designer Max Miedinger. His goal is to design a new sans serif font that can compete in the Swiss market, as a neutral font that should not be given any additional meaning. The main influence on Helvetica was Akzidenz-Grotesk from Berthold; Hoffman's scrapbook of proofs of the design shows careful comparison of test proofs with snippets of Akzidenz-Grotesk.[10] Its 'R' with a curved tail resembles Schelter-Grotesk, another turn-of-the-century sans-serif sold by Haas.[4][10][11] Wolfgang Homola comments that in Helvetica "the weight of the stems of the capitals and the lower case is better balanced" than in its influences.[12]

Attracting considerable attention on its release as Neue Haas Grotesk (Nouvelle Antique Haas in French-speaking countries),[lower-alpha 1] Stempel and Linotype adopted Neue Haas Grotesk for release in hot metal composition, the standard typesetting method at the time for body text, and on the international market.[14]

In 1960, its name was changed by Haas' German parent company Stempel to Helvetica in order to make it more marketable internationally; it comes from the Latin name for the pre-Roman tribes of what became Switzerland. Intending to match the success of Univers, Arthur Ritzel of Stempel redesigned Neue Haas Grotesk into a larger family.[15][16] The design was popular: Paul Shaw suggests that Helvetica "began to muscle out" Akzidenz-Grotesk in New York City from around summer 1965, when Amsterdam Continental, which imported European typefaces, stopped pushing Akzidenz-Grotesk in its marketing and began to focus on Helvetica instead.[17][18] It was also made available for phototypesetting systems, as well as in other formats such as Letraset dry transfers[19] and plastic letters,[20] and many phototypesetting imitations and knock-offs were rapidly created by competing phototypesetting companies.[21][22]

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Linotype licensed Helvetica to Xerox, Adobe and Apple, guaranteeing its importance in digital printing by making it one of the core fonts of the PostScript page description language.[23][24] This led to a version being included on Macintosh computers and a metrically-compatible clone, Arial, on Windows computers. The rights to Helvetica are now held by Monotype Imaging, which acquired Linotype; the Neue Haas Grotesk digitisation (discussed below) was co-released with Font Bureau.[4]

Characteristics

- Tall x-height, which makes it easier to read at distance.

- Tight spacing between letters.

- An oblique rather than italic style, a common feature of almost all grotesque and neo-grotesque typefaces.

- Wide capitals of uniform width, particularly obvious in the wide 'E' and 'F'.

- Square-looking 's'.

- Bracketed top flag of '1'.

- Rounded off square tail of 'R'.

- Concave curved stem of '7'.

- Two-storied 'a' (with curves of bowl and stem), a standard neo-grotesque feature, and single-storey 'g'

Helvetica can't do everything...it can be really weak in small sizes. Shapes like 'C' and 'S' curl back into themselves, leaving tight "apertures"—the channels of white between a letter's interior and exterior... The lowercase 'e', the most common letter in English and many other languages, takes an especially unobliging form. These and other letters can be a pixel away from being some other letter.

Tobias Frere-Jones[25]

Like many neo-grotesque designs, Helvetica has narrow apertures, which limits its legibility onscreen and at small print sizes. It also has no visible difference between upper-case 'i' and lower-case 'L', although the number 1 is quite identifiable with its flag at top left.[26][27] Its tight, display-oriented spacing may also pose problems for legibility.[28] Other fonts intended for legibility at small sizes such as Verdana, Meta, Trebuchet, or a monospace font such as Courier, which makes all letters quite wide, may be more appropriate than Helvetica.

Usage examples

Logo of Cassina S.p.A.

Logo of Cassina S.p.A..tif.jpg.webp) Sign in Vienna, 1973

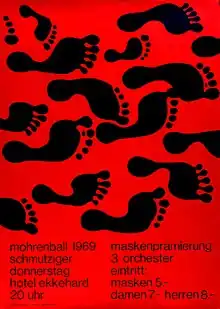

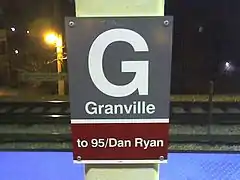

Sign in Vienna, 1973 Chicago 'L' signage

Chicago 'L' signage National Film Board of Canada logo

National Film Board of Canada logo UK government publication

UK government publication 1964 poster for Les Diaboliques

1964 poster for Les Diaboliques

Helvetica is among the most widely used sans-serif typefaces.[29] Versions exist for Latin, Cyrillic, Hebrew, Greek, Japanese, Korean, Hindi, Urdu, Khmer, and Vietnamese alphabets. Chinese faces have been developed to complement Helvetica.

Helvetica is a common choice for commercial wordmarks, including those for 3M (including Scotch Tape), Adult Swim, American Apparel, BASF, Behance, Blaupunkt, BMW, Diaspora, ECM, Funimation, General Motors (until 2021), J. C. Penney, Jeep, Kaiser Permanente, Kawasaki, Knoll, Kroger, LG (until 2015), Lufthansa, Motorola, Nestlé, Oath Inc., Panasonic, Parmalat, Philippine Airlines, Sears, Seiko Epson, Skype, Target, Texaco, Tupperware, Viceland, and Verizon.[30][31] Apple used Helvetica as the system typeface of iOS until 2015.[32][33]

Helvetica has been widely used by the U.S. government; for example, federal income tax forms are set in Helvetica, and NASA used the type on the Space Shuttle orbiter.[34] Helvetica is also used in the United States television rating system. The Canadian government also uses Helvetica as its identifying typeface, with three variants being used in its corporate identity program, and encourages its use in all federal agencies and websites.[35]

.jpg.webp)

In the European Union, Helvetica is legally required to be used for health warnings on tobacco products such as cigarettes.[37]

Helvetica is commonly used in transportation settings.[38] New York City's Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) adopted Helvetica for use in signage in 1989. From 1970 to 1989, the standard font was Standard Medium, an American release of Akzidenz-Grotesk, as defined by Unimark's New York City Transit Authority Graphic Standards Manual. The MTA system is still rife with a proliferation of Helvetica-like fonts, including Arial, in addition to some old signs in Medium Standard, and a few anomalous signs in Helvetica Narrow.[39][40][41] Helvetica is also used in the Washington Metro, the Chicago 'L', Philadelphia's SEPTA, and the Madrid Metro.[42] Amtrak used the typeface on the "pointless arrow" logo, and it was adopted by Danish railway company DSB for a time period.[43] In addition, the former state-owned operator of the British railway system developed its own Helvetica-based Rail Alphabet font, which was also adopted by the National Health Service and the British Airports Authority.[44] The Helvetica 77 variation is used in street and house signage in Riga and other municipalities in Latvia, although common road signage in the country uses a version of DIN 1451.[45]

The typeface was displaced from some uses in the 1990s to the increased availability of other fonts on digital desktop publishing systems, and criticism from type designers including Erik Spiekermann and Martin Majoor, both of whom have criticised the design for its omnipresence and overuse.[4][46] Majoor has described Helvetica as 'rather cheap' for its failure to move on from the model of Akzidenz-Grotesk.[47]

Road signs in Japan and South Korea formerly used Helvetica.

IBM used Helvetica Neue as its corporate typeface until 2017, spending over $1m annually on licensing fees.[48] It switched in 2017 to the custom IBM Plex family, concluding that a custom open-source typeface would be more distinctive and practical, as it could be freely distributed and installed without rights issues.[48][49]

In 2019, the Switzerland national football team began using Helvetica for its kit, which it wore for the UEFA Euro 2020 tournament.[50]

Liebherr Group previously used Helvetica Neue typeface as corporate identity until switched to HVD Fabrikat typeface in 2021.

Media coverage

An early essay on Helvetica's public image as a font used by business and government was written in 1976 by Leslie Savan, a writer on advertising at the Village Voice.[51] It was later republished in her book The Sponsored Life.[52]

In 2007, Linotype GmbH held the Helvetica NOW Poster Contest to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the typeface.[53][54] Winners were announced in the January 2008 issue of the LinoLetter.

In 2007, director Gary Hustwit released a documentary film, Helvetica (Plexifilm, DVD), to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the typeface. In the film, graphic designer Wim Crouwel said, "Helvetica was a real step from the 19th century typeface... We were impressed by that because it was more neutral, and neutralism was a word that we loved. It should be neutral. It shouldn't have a meaning in itself. The meaning is in the content of the text and not in the typeface." The documentary also presented other designers who associated Helvetica with authority and corporate dominance, and whose rebellion from Helvetica's ubiquity created new styles.

From April 2007 to March 2008, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City displayed an exhibit called "50 Years of Helvetica".[55] In 2011 the Disseny Hub Barcelona displayed an exhibit called Helvetica. A New Typeface?. The exhibition included a timeline of Helvetica over the last fifty years, its antecedents and its subsequent influence, including in the local area.[56]

In 2011, one of Google's April Fools' Day jokes centered on the use of Helvetica. If a user attempted to search for the term "Helvetica" using the search engine, the results would be displayed in the font Comic Sans.[57]

Variants

A large number of variants of Helvetica were rapidly released to expand on its popularity, including new weights and languages. Linotype confessed by the time of a 1976 advertorial that things had become somewhat confused: "the series was not planned as a whole from its conception...the series is not as uniform as Univers".[58][59]

Helvetica Light

Helvetica Light was designed by Stempel's artistic director Erich Schultz-Anker, in conjunction with Arthur Ritzel.[60]

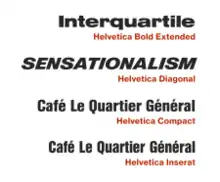

Helvetica Inserat

Helvetica Inserat (German for advertisement) is a version designed primarily for use in the advertising industry: this is a narrow variant that is tighter than Helvetica Black Condensed. It gives the glyphs an even larger x-height and a more squared appearance, similar to Schmalfette Grotesk. Adobe's release notes date it to 1966 and state that it originated with Stempel.[61]

Helvetica Compressed (1966)

Designed by Matthew Carter and Hans-Jürg Hunziker for cold type.[62] It shares some design elements with Helvetica Inserat, but uses a curved tail in Q, downward pointing branch in r, and tilde bottom £. Carter has said that in practice it was designed to be similar to Schmalfette Grotesk and to compete in this role with British designs Impact and Compacta, as this style was popular at the time.[63] Carter, who also later designed Helvetica Greek, had designed a modernised version of Akzidenz-Grotesk for signage at Heathrow in 1961, and commented later "if we'd known about [Helvetica] I'm sure we would have used it, since it's a much better typeface than the one I drew. But the typesetting trade was very conservative then, and new type designs traveled slowly."[33][64] The family consists of Helvetica Compressed, Helvetica Extra Compressed and Helvetica Ultra Compressed fonts. It has been digitised, for instance in the Adobe Helvetica release.

Helvetica Rounded (1978)

Helvetica Rounded is a version containing rounded stroke terminators, released for bold weights. Linotype's release notes date it to 1978.[65]

Helvetica Narrow

Helvetica Narrow is a version where its width is between Helvetica Compressed and Helvetica Condensed. The font was developed when printer ROM space was very scarce, so it was created by mathematically squashing Helvetica to 82% of the original width, resulting in distorted letterforms, with vertical strokes narrowed but horizontals unchanged.[66] Because of the distortion problems, Adobe dropped Helvetica Narrow in its release of Helvetica in OpenType format, recommending users choose Helvetica Condensed instead.[67]

Helvetica Textbook

Helvetica Textbook is an alternate design of the typeface, which uses 'schoolbook' stylistic alternates to increase distinguishability: a seriffed capital 'i' and 'j' to increase distinguishability, a 'q' with a flick upwards and other differences. The 'a', 't' and 'u' are replaced with designs similar to those in geometric sans-serifs such as those found in Futura and Akzidenz-Grotesk Schulbuch.[68] FontShop's FF Schulbuch is similar.[69][70]

Language variants

Helvetica Greek has gone through several versions. Letraset designed a semi-official version for their dry transfer lettering system, available by 1970, which sold well but was considered unidiomatic by Linotype.[71] Linotype published a 1971 version designed by Matthew Carter which was available for phototypesetting and so for general purpose printing such as extended text.[71][72][63][73][74][75] Carter felt in 1974 that the Letraset version was "a poor thing" and Linotype's version was "the real one" but that Letraset's was well-enough accepted in Greece that he felt it had "caused resistance to our version".[71] Linotype published a new version in 2001 designed by John Hudson at Tiro Typeworks.[71][72]

The Cyrillic version was designed in-house in the 1970s at D Stempel AG, then critiqued and redesigned in 1992 under the advice of Jovica Veljović, although a pirated version had already been created in 1963 by Russian designers Maxim Zhukov and Yuri Kurbatov.[76][77][78]

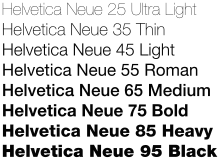

Neue Helvetica (1983)

Helvetica Neue (German pronunciation: [ˈnɔʏ̯ə]) is a reworking of the typeface with a more structurally unified set of heights and widths. Other changes include improved legibility, heavier punctuation marks, and increased spacing in the numbers.

Neue Helvetica uses a numerical design classification scheme, like Univers. The font family is made up of 51 fonts including nine weights in three widths (8 in normal width, 9 in condensed, and 8 in extended width variants) as well as an outline font based on Helvetica 75 Bold Outline (no Textbook or rounded fonts are available). Linotype distributes Neue Helvetica on CD.[79] Helvetica Neue also comes in variants for Central European and Cyrillic text.

It was developed at D. Stempel AG, a Linotype subsidiary. The studio manager was Wolfgang Schimpf, and his assistant was Reinhard Haus; the manager of the project was René Kerfante. Erik Spiekermann was the design consultant and designed the literature for the launch in 1983.[80][81] Figures were widened and some condensed weights changed from having nearly flat-sided verticals to a more continuous curve throughout the entire height.[82]

Designer Christian Schwartz, who would later release his own digitisation of the original Helvetica designs (see below), expressed disappointment with this and other digital releases of Helvetica: "digital Helvetica has always been one-size-fits-all, which leads to unfortunate compromises...the spacing has ended up much looser than Miedinger's wonderfully tight original at display sizes but much too tight for comfortable reading at text sizes."[83]

iOS used first Helvetica then Helvetica Neue[84] as its system font. All releases of macOS prior to OS X Yosemite used Lucida Grande as the system font. The version of Helvetica Neue used as the system font in OS X 10.10 is specially optimised; Apple's intention is to provide a consistent experience for people who use both iOS and OS X.[85][86] Apple replaced Helvetica Neue with the similarly looking San Francisco in iOS 9 and OS X El Capitan.[87]

Neue Helvetica Georgian (2015)

It is a version with Georgian script support. Designed by Akaki Razmadze at Monotype Bad Homburg.[88]

Only OpenType CFF and TTF font formats were released.

The family includes eight fonts in eight weights and one width, without italics (25, 35, 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, 95).

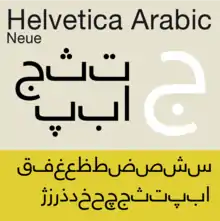

Helvetica World

Helvetica World supports Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, Hebrew, and Vietnamese scripts.[89]

The family consists of four fonts in two weights and one width, with complementary italics.

The Arabic glyphs were based on a redesigned Yakout font family from Linotype. Latin kerning and spacing were redesigned to have consistent spacing.[90] John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks designed the Hebrew glyphs for the font family,[91] as well as the Cyrillic, and Greek letters.[92]

Neue Helvetica W1G (2009)

It is a version with Latin Extended, Greek, Cyrillic scripts support. Only OpenType CFF font format was released.

The family includes the fonts from the older Neue Helvetica counterparts, except Neue Helvetica 75 Bold Outline. Additional OpenType features include subscript/superscript.

Neue Helvetica Arabic (2009)

Designed by Lebanese designer Nadine Chahine,[93] it is a version with Arabic script support. Only OpenType TTF font format was released.[94]

The family includes three fonts in three weights and one width, without italics (45, 55, 65).

(Neue) Helvetica Thai (2012)

Thai font designer Anuthin Wongsunkakon of Cadson Demak Co. created Thai versions of Helvetica and Neue Helvetica fonts.[95][96] The design uses loopless terminals in Thai glyphs,[97][98] which had also been used by Wongsunkakon's previous design, Manop Mai (New Manop).[99]

Neue Helvetica World (2017)

Designed by Nadine Chahine, Linotype Design Studio, Monotype Design Studio and Edik Ghabuzyan, it is a version of Neue Helvetica with support of Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Thai, Armenian, Georgian and Vietnamese scripts for total 181 languages, and complete support of Unicode block u+0400.[100][101][102][103] Published in November 2017 by Linotype, it was released in Truetype and OpenType CFF formats.

Neue Helvetica eText (2011)

It is a version of Neue Helvetica optimised for on-screen use, designed by Akira Kobayashi of Monotype Imaging. Changes from Neue Helvetica include more open spacing.[104] Unlike Helvetica, the capitals are reduced in size so the lower-case ascenders rise above them, a common feature associated with text typefaces.[82][105]

The family includes eight fonts in four weights and one width, with complementary italics (45, 46, 55, 56, 65, 66, 75, 76). OpenType features include numerators/denominators, fractions, ligatures, scientific inferiors, subscript/superscript.[106]

Neue Haas Grotesk (2010)

Christian Schwartz's digitisation is based on original settings of the metal type and uses the typeface's original name.[107][108][109][110] It was released by Linotype (later Monotype Imaging), Commercial Type, and Font Bureau with an article on the history of Helvetica by Professor Indra Kupferschmid.[10]

Unlike earlier digitisations, Schwartz created two different optical sizes for body text and display sizes, which have different spacing metrics giving tighter spacing at display size and looser spacing to increase legibility in text. The release includes a number of features not present on digitisations branded as Helvetica, stylistic alternates such as separate punctuation sets for upper- and lower-case text, "modernist" cedilla designs styled to match the comma and reduced-height numbers to blend into extended text.[111][lower-alpha 2] The Text optical size of Neue Haas Grotesk also provides stylistic alternates for a straight-legged upper case "R", while the Display optic size provides stylistic alternates for a straight-legged upper case "R" and a lower case "a" without tail.[112][113] It originated from an abandoned redesign plan for The Guardian newspaper. Writing for Typographica, Matthew Butterick described the release as better than any previous digital release of Helvetica “it’s never looked better”.[114] Users include Bloomberg Businessweek and the Whitney Museum.[115][116] Schwartz's company Commercial Type have additionally developed a companion monospaced version, agate version for small sizes and stencil font.[117] The release does not include condensed weights or support for Greek and Cyrillic.

Availability

Users of Windows 10 can download three weights of the Text optical size (Regular, Medium, and Bold), including italics, by enabling the "Pan-European Supplemental Fonts" optional feature.[118][119] Users of Windows 11 can obtain Neue Haas Grotesk in the same way.[120]

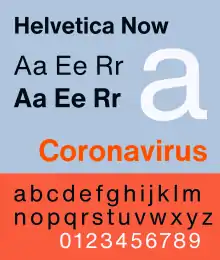

Helvetica Now (2019)

| |

| Category | Sans-serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Neo-grotesque sans-serif |

| Designer(s) | Jan Hendrik Weber and Charles Nix |

| Foundry | Monotype |

| Date released | 2019 |

| Design based on | Helvetica Neue |

In April 2019, Monotype announced an update of Neue Helvetica called "Helvetica Now", designed by Jan Hendrik Weber and Charles Nix of Monotype Imaging.[121][122][123] The family has one width in three optical sizes, Text, Micro and Display in 8, 6, and 10 weights respectively.[124] The condensed version corresponding to these optical sizes and weights was published later. Features include circled figures and redesigned arrow and @ glyphs. It also includes a number of alternate characters including curled lower-case L, spurless rounded G, a straight-legged R (found in Neue Haas Grotesk), single-story a (found in Helvetica Textbook) and lowercase u without a spur.[125][126]

Helvetica clones

Derivative designs based on Helvetica were rapidly developed, taking advantage of the lack of copyright protection in the phototypesetting font market of the 1960s onward.[21][127] Some of these were straight clones, simply intended to be direct substitutes.[128] Many of these are almost indistinguishable from Helvetica, while some add subtle differences.

Substitute Helvetica designs that have survived into or originated during the digital period have included Monotype's Arial, Compugraphic's CG Triumvirate, ParaType's Pragmatica, Bitstream's Swiss 721, URW++'s Nimbus Sans and Scangraphic's Europa Grotesk.[21][129] Berthold itself responded to Helvetica's popularity with Akzidenz-Grotesk Buch, effectively a Helvetica clone.[130][131][132][133] Besides Helvetica imitations, Helvetica was available in custom derivatives with unusual special-order characters for many years, notably a straight-legged 'R' and round-topped 'A'.[10] CNN uses a custom derivative, "CNN Sans", which has a '1' with a base and larger x-height.[134][135][136]

Nimbus Sans

URW (later URW++) under the leadership of Peter Karow produced a modification of Helvetica called Nimbus Sans.[130] This is an extremely large font family with optical sizes spaced for different sizes of text and other variants such as stencil styles.[137] Florian Hardwig has described its display-oriented styles, with tight spacing, as more reminiscent of Helvetica as used in the 1970s from cold type than any official Helvetica digitisation.[138][139]

Arial and MS Sans Serif

Monotype's Arial, created for IBM and also used by Microsoft, is indistinguishable by most non-specialists.[140] Matthew Carter, who was a consultant for IBM during its design process, describes it as "a Helvetica clone, based ostensibly on their Grots 215 and 216" (Monotype's old 1920s sans-serif family, popular in British trade printing in the metal type period, and itself based on the Bauer Venus-Grotesk family).[23] Differences include:

- Helvetica's strokes are typically cut either horizontally or vertically. This is especially visible in the t, r, f, and C. Arial employs slanted stroke cuts, following Monotype Grotesque.

- Helvetica's G has a spur at bottom right; Arial does not, but instead has a vertical stroke connecting the curved portion to the crossbar.

- The tail of Helvetica's R is more upright whereas Arial's R is more diagonal.

- The number 1 of Helvetica has a square angle underneath the upper spur, Arial has a curve.

- The Q glyph in Helvetica has a straight cross mark, while the cross mark in Arial has a slight curve.

The design was created to substitute for Helvetica: Arial (and many other clones of the period) are metrically identical to the PostScript version of Helvetica, so that a document designed in Helvetica could be displayed and printed correctly without IBM having to pay Linotype for a Helvetica license on its printers.[23][141][142]

Microsoft's "Helv" design, later known as "MS Sans Serif", is a sans-serif typeface that shares many key characteristics to Helvetica, including the horizontally and vertically aligned stroke terminators and more-uniform stroke widths within a glyph.

Free Helvetica substitute fonts

Nimbus Sans L, a version of URW's Nimbus Sans spaced to match the standard Linotype/PostScript version of Helvetica, was released under the GNU General Public License in 1996, and donated to the Ghostscript project to create a free PostScript alternative.[143][144] It (or a derivative) is used by much open-source software such as R as a system font.[145][146] A derivative of this family known as "TeX Gyre Heros" has been prepared for use in the TeX scientific document preparation software, and since 2009 general under the GUST font license.[147][148]

FreeSans is a free font descending from URW++ Nimbus Sans L, which in turn descends from Helvetica.[149] It is one of free (GPL) fonts developed in GNU FreeFont project, first published in 2002.

Liberation Sans is a metrically equivalent font to Arial developed by Steve Matteson at Ascender and published by Red Hat under the SIL Open Font License.[150][151] It is used in some Linux distributions as default font replacement for Arial.[152] Oracle funded the additional development of Liberation Sans Narrow in 2010.[153][154] Google commissioned a variation named Arimo for Chrome OS.

Much more loosely, Roboto was developed by Christian Robertson of Google as the system font for its Android operating system; this has a more condensed design with the influence of straight-sided geometric designs like DIN 1451.

Derivative designs

Some fonts based on Helvetica are intended for different purposes and have clearly different designs. Digital-period font designer Ray Larabie has commented that in the 1970s "everyone was modifying Helvetica with funky curls, mixed-case and effects".[155] Indeed, in one 1973 competition to design new fonts, three of the 20 winners were decorative designs inspired by Helvetica.[156]

Zhukov and Kurbatov version

In 1963, two students at the Moscow Print Institute designed their own version of Helvetica, one of whom, Maxim Zhukov, would become one of the Soviet Union's most prominent typographers. Zhukov and his partner Yuri Kurbatov used upright cursive forms for several of the lowercase letters, which allowed for several of the Helvetica forms to be transferred more directly into Cyrillic.

Their version received widespread use in phototypesetting, especially among other students at the Moscow Print Institute, despite never being commercially released. Zhukov and Kurbatov attempted to publish the typeface in 1964 but were rejected due to the font’s being too closely associated with capitalism; this was one of the major factors as to why an official Cyrillic Helvetica, Pragmatica, would not be released in the Soviet bloc until perestroika in 1989.[78][157][lower-alpha 3]

Forma (1968)

Created by Aldo Novarese at the Italian type foundry Nebiolo, Forma was a geometric-influenced derivative of Helvetica with a 'single-storey' 'a' and extremely tight spacing in the style of the period.[158][159][160] It was offered with 'request' stylistic alternates imitating Helvetica more closely.[158][161] Forma has been digitised by SoftMaker as "Formula" and (in a much more complete version with optical sizes) as Forma DJR by David Jonathan Ross at Font Bureau for Tatler magazine.[162]

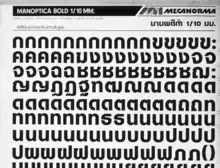

Manoptica

Manoptica (1973) was an early effort to adapt Helvetica to the Thai script. It is named after and designed by Manop Srisomporn, who designed several typefaces for Thai using the same innovations he used for Manoptica (such as an adaptation of Eurostile). It was highly influential in Thai typography in that it popularized the removal of the small loops and other flourishes that had theretofore been distinguishing marks on Thai characters and adopted letter forms that bore strong resemblance to Latin letters. It became a widely popular style in advertising and influenced other simplified typefaces for Thai in the following decades.[163] The adoption of loopless typefaces remains a source of controversy in Thai typography.[164]

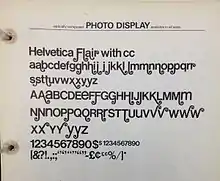

Helvetica Flair and others

Designed by Phil Martin at Alphabet Innovations, Helvetica Flair is an unauthorised phototype-period redesign of Helvetica adding swashes and unicase-inspired capitals with a lower-case design. Considered a hallmark of 1970s design, it has never been issued digitally. It is considered to be a highly conflicted design, as Helvetica is seen as a spare and rational typeface and swashes are ostentatious: font designer Mark Simonson described it as "almost sacrilegious". Martin would later claim to have been accused of "typographic incest" by one German writer for creating it.

Helvetica Flair was one of several derivative fonts created by Martin in the 1970s (and a particularly legally questionable one, since it was directly named 'Helvetica').[165][166] Martin also drew 'Heldustry', a fusion of Helvetica with Eurostile,[167] and 'Helserif', a redesign of Helvetica with serifs,[168] and these have both been digitised.[128][169][170]

Shatter LET (1973)

Designed by Vic Carless, Shatter assembles together slices of Helvetica to make a typeface that seems to be in motion, or broken and in pieces.[171] It was published by Letraset after jointly winning their 1973 competition to design new fonts.[156]

Writing in 2014, Tim Spencer praised the design for its ominous effect, writing that it offered "glitch-like mechanical aggression [and] cold, machine-induced paranoia. It attacked the Establishment’s preferred information typography style with a sharp edge and recomposed it in a jarring manner that still makes your eyes skitter and your brain tick trying to recompose it. Shatter literally sliced up Swiss modernist authority."[172]

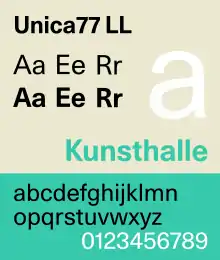

Unica

Unica by Team ’77 (André Gürtler, Christian Mengelt and Erich Gschwind) is as a hybrid of Helvetica, Univers and Akzidenz-Grotesk. It was developed in the 1970s for electronic on-screen phototypesetting and released in 1980. As phototypesetting was soon replaced by desktop publishing and because of a legal dispute, the typeface rapidly disappeared from the market. In mid 2010s, two digital versions were released: the Swiss foundry Lineto released LL Unica77 with input from Christian Mengelt,[173][174] while Linotype released Neue Haas Unica.[175]

Chalet

House Industries’ Chalet family is a series of fonts based on Helvetica, inspired by its many derivatives and adaptations in post-war design, and organised by "date" to '1960' (conventional), '1970' and '1980' (both more radically altered and "science fiction" in feel).[176] House Industries, who are known for outlandish font marketing methods, promoted Chalet through presenting it as inspired by the branding and career progression of a fictitious Swiss haute couture designer, "René Chalet" (Chalet being French for a small wooden house, so a play on the design company’s name).[177][178][179]

Coolvetica

In the digital period, Canadian type designer Ray Larabie has released several digital fonts based upon Helvetica. The most widely known and distributed of these is Coolvetica, which Larabie introduced in 1999; Larabie stated he was inspired by Helvetica Flair, Chalet, and similar variants in creating some of Coolvetica's distinguishing glyphs (most strikingly a swash on capital 'G', lowercase 'y' based on the letterforms of 'g' and 'u,' and a fully curled lowercase 't'), and chose to set a tight default spacing optimised for use in display type.[180] Larabie's company Typodermic offers Coolvetica in a wide variety of weights as a commercial release, with the semi-bold as freeware taster. As of 2017, the semi-bold remains Larabie's most popular font.[181][182][183] Larabie has also taken inspiration from Helvetica in some of his other designs, including Movatif and GGX88.[184][185]

Notes

- "Antique" is a term used in French for sans-serifs (for instance Antique Olive), although in English it traditionally historically referred to slab-serifs.[13]

- This feature was also included in Robert Slimbach's neogrotesque Acumin (2014) for Adobe.[105]

- The lowercase forms of Sowjietische Haas Grotesk were digitized as "Soyuz Grotesk" by Roman Goritsky and released into the public domain by The Temporary State. Goritsky added a Latin script, which he reconstructed in the same way Sowjietische Haas Grotesk had been constructed from Helvetica but in reverse, by using the Cyrillic forms and adapting them to Latin.[77][78]

References

- Kupferschmid, Indra. "Combining Type With Helvetica". FontShop (archived). Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Berry, John. "A Neo-Grotesque Heritage". Adobe Systems. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Shinn, Nick (2003). "The Face of Uniformity" (PDF). Graphic Exchange. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Kupferschmid, Indra. "I had never loved Helvetica". Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- Gerstner, Karl (1963). "A new basis for the old Akzidenz-Grotesk (English translation by Forgotten Shapes)" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Gerstner, Karl (1963). "Die alte Akzidenz-Grotesk auf neuer Basis" (PDF). Der Druckspiegel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Helvetica (Documentary). 2007-09-12.

- Shaw, Paul. "Helvetica and Univers addendum". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Shaw, Paul. "The Univers of Helvetica: A Tale of Two Typefaces". Print. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- Kupferschmid, Indra. "Neue Haas Grotesk - History". Font Bureau. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Langer, Axel. "One Typeface, Two Fathers". Helvetica Forever. University of Applied Sciences Düsseldorf. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Homola, Wolfgang. "Type design in the age of the machine. The 'Breite Grotesk' by J. G. Schelter & Giesecke" (PDF). University of Reading (archived). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ""Nouvelle Antique Haas" aka "Neue Haas Grotesk" aka "Helvetica" promotional, by Fritz Büler, Walter Bosshardt, 1959". Flickr. Herb Lubalin Study Center. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Montrose-Helker, William. "Post-War Type Marketing: A comparative study of three European type foundries during the 1950s and 1960s". University of Reading. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "myfonts: Arthur Ritzel". New.myfonts.com. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Shaw, Paul. "Helvetica & Univers". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Shaw, Paul. "From the Archives no. 15—Helvetica and Standard". Paul Shaw Letter Design (blog). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Shaw, Paul. "From the Archives no. 17—More on Helvetica in the United States". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Müller, Lars; Malsy, Victor; Langer, Axel; Kupferschmid, Indra (2009). Helvetica Forever: Story of a Typeface. Baden, Switzerland: Lars Müller. ISBN 978-3037781210.

- Shaw, Paul. "Blue Pencil no. 19—Helvetica and the New York City Subway System". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Simonson, Mark. "The Scourge of Arial". Mark Simonson Studio Notebook. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

Many type manufacturers in the past have done knock-offs of Helvetica that were indistinguishable or nearly so. For better or worse, in many countries—particularly the U.S.—while typeface names can be protected legally, typeface designs themselves are difficult to protect. So, if you wanted to buy a typesetting machine and wanted the real Helvetica, you had to buy Linotype. If you opted to purchase Compugraphic, AM, or Alphatype typesetting equipment, you couldn’t get Helvetica. Instead you got Triumvirate, or Helios, or Megaron, or Newton, or whatever. Every typesetting manufacturer had its own Helvetica look-alike. It’s quite possible that most of the “Helvetica” seen in the ’70s was actually not Helvetica.

- Craig, James; Malmstrom, Margit (1978). Phototypesetting: a design manual (1st ed.). New York: Watson-Guptill. p. 35. ISBN 9780823040117.

Helvetica is, without a doubt, the most widely used sans serif typeface.

- Shaw, Paul; Carter, Matthew; McDonald, Rod. "Blue Pencil no. 18—Some history about Arial". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Simonson, Mark. "Monotype's Other Arials". Mark Simonson Studio. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Covert, Adrian (3 June 2014). "Why Apple's New Font Won't Work On Your Desktop". FastCoDesign. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Spiekermann, Erik. "Helvetica Sucks". Spiekermann blog. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Spiekermann, Erik. "Distinct lettershapes are important. Or can you work out this code? 1, I or l?". Twitter. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Spolsky, Joel (24 October 2001). "User Interface Design For Programmers". Joel On Software. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Uses of Helvetica". Fonts In Use.

- "BBC News - Helvetica at 50". 2007-05-09. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- Ferguson, Brad (24 July 2015). "Helvetica: The Backlash". Print. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Daring Fireball: 4". John Gruber.

- Rawsthorn, Alice (April 2007). "Helvetica: The little typeface that leaves a big mark". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Helvetica (Documentary). 2007-09-12.

- "Federal Identity Program Manual - 1.1 Design". Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

A consistent typography is fundamental to corporate identity, and three faces from the Helvetica type family have been adopted for purposes of the FIP. They were chosen for their versatility, excellent legibility and contemporary design.

- Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey (7 May 2013). "Six Beautiful Artefacts From The Dawn Of Digital Typography". Gizmodo. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Article 9(4)(a) of Directive 2014/40/EU.

- "A Brief History of Fonts in Transit" (PDF). livewellcollaborative.org/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- Shaw, Paul. "The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway". AIGA. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Bierut, Michael (26 March 2011). "When in Helvetica". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Lee, Jennifer. "How Helvetica Took Over the Subway". New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Elementos Básicos de Identidad Corporativa de Metro de Madrid" [Basic Elements of the Corporate Identity of the Metro of Madrid] (PDF). metromadrid.es (in Spanish). Metro de Madrid. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-23.

- "Eye blog » Rue Britanica.Typeface name changes after Eye magazine goes to press". Blog.eyemagazine.com. 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Walters, John. "New Rail Alphabet". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Par ielu un laukumu nosaukuma zīmju, ēku, telpu grupu numura zīmju un virziena rādītāju uz infrastruktūras, kultūras vai tūrisma objektiem izvietošanas kārtību Rīgas pilsētā". LIKUMI.LV (in Latvian). Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- Spiekermann, Erik (1987). "Post Mortem or how I once designed a typeface for Europe's biggest company" (PDF). Baseline (9): 6–9. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Majoor, Martin (Spring 2007). "Inclined to be dull". Eye. Vol. 16, no. 63. pp. 33–7. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Quito, Anne (10 November 2017). "IBM has freed itself from the tyranny of Helvetica". Quartz. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Czarnecki, Lucas. "Can IBM Plex topple Helvetica?". Type. Archived from the original on 2018-05-01. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "PUMA chose Helvetica font for Switzerland's new jersey". nss magazine. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- Lupton, Ellen. "Forever Helvetica". Metropolis Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Savan, Leslie (1994). The Sponsored Life: Ads, TV, and American Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 9781439904909.

- "Linotype Announces Helvetica NOW Poster Contest". Creativepro.com. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Helvetica NOW Poster Contest". Linotype.com. 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Exhibitions 2007: 50 Years of Helvetica". Museum of Modern Art, New York. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- Helvetica. A New Typeface? Archived 2012-08-28 at the Wayback Machine at Disseny Hub Barcelona

- Pickel, Janet (1 April 2011). "April Fool's Day: Helvetica becomes Comic Sans and Gmail Motion is on the move". The (Harrisburg, PA) Patriot-News. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- Shaw, Paul. "From the Archives no. 26—Helvetica and Univers". Paul Shaw Letter Design. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- "Everything you ever wanted to know about Helvetica – but were afraid to ask". Upper & Lower Case. 3 (1): 43–6. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- de Jong, Cees W; Purvis, Alston W; Friedl, Friedrich (2005). Creative Type: A Sourcebook of Classic and Contemporary Letterforms. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50051229-6. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Helvetica Inserat". MyFonts. Adobe. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Sherman, Nick; Carter, Matthew (26 April 2015). "Helvetica Compressed". Flickr. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

Helvetica Compressed was planned as a three-part family [to fit into] the Linofilm’s unit system…I designed Helvetica Compressed and Helvetica Extra Compressed, on my own before Hans-Jürg joined the company. They were released in 1966. Hans-Jürg designed the Ultra Compressed under my eye. It was released in 1968…part of a craze for condensed grots in Europe in the ’60s that encouraged me to propose to Mike Parker that I should design a series when I joined Merg[enthaler] in 1965. There was no client in mind for Helvetica Compressed when we did it.

- Drucker, Margaret Re; essays by Johanna; Mosley, James (2003). Typographically Speaking: The Art of Matthew Carter (2. ed.). New York: Princeton Architectural. pp. 41, 53 etc. ISBN 9781568984278.

- Webster, Garrick (19 January 2011). "Matthew Carter". Computer Arts. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

We did a sans-serif typeface, which, if you look at it today, you'd think was a rip-off of Helvetica. But we'd never seen Helvetica in 1961 in London, although it had been produced in Switzerland near Basle at the Haas foundry in 1957. Even if we had seen it, and wanted to have it typeset in London, we'd have had to get on a plane and fly to Basle and have it typeset there, because the British typesetting trade was so conservative that typefaces like that were simply unobtainable.

- "Helvetica rounded – the rounded version of the classic Helvetica". Linotype.com. Linotype. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Felici, James (15 April 2010). "The Call of the Wide". Creative Pro. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Type 1 ("PostScript") to OpenType font conversion". Adobe. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Helvetica Textbook". FontShop. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Coles, Stephen (26 August 2012). "Wikipedia Redefined". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Coles, Stephen (20 March 2016). "Design Museum". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Lekka, Helena (2017). Linotype's design of new Greek typefaces for photocomposition in the Greek printing market, 1970-1980 (Thesis). University of Reading.

- Lekka, Helena. "The design of Helvetica Greek for photocomposition". Academia.edu. University of Reading. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Re, Margaret (2005). "A Typographic Jubilee for Matthew Carter" (PDF). Typo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "TYPO.18" (PDF) (magazine). CZ: Svettisku. December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-19.

- Carter, Matthew (1996). Macrakis, Michael (ed.). Greek Letters: From Tablets to Pixels (1st ed.). New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Press. p. 175. ISBN 9781884718274.

- "Helvetica Cyrillic". Fonts. Adobe. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Samarskaya, Ksenya. "Soyuz Grotesk". Typographica. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Gornitsky, Roman. "Soyuz Grotesk: release notes". The Temporary State. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Linotype Library presents entire New Helvetica family on a single CD". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Who Made Helvetica Neue?" Archived June 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, typophile.com

- Kupferschmid, Indra. "Neue Helvetica Entdeckung!". Kupferschrift. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Strizver, Ilene (6 December 2017). "Helvetica vs. Neue Helvetica: The Same but Different". Creative Pro. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Schwartz, Christian. "Neue Haas Grotesk". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Gruber, John (29 June 2010). "Daring Fireball: 4". daringfireball.net. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

It’s a subtle change, but Apple has changed the system font for the iPhone 4, from Helvetica to Helvetica Neue. The change is specific to the iPhone 4 hardware (or more specifically, the Retina Display), not iOS 4.

- "OS X Human Interface Guidelines: Designing for Yosemite". Apple Developer. Apple, Inc. 2014-10-16. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

The use of Helvetica Neue also gives users a consistent experience when they switch between iOS and OS X.

- Bigelow, Charles; Holmes, Kris. "What's the Difference between Lucida Grande and Helvetica Neue?". Bigelow & Holmes. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Stinson, Liz (2015-06-09). "Why Apple Abandoned the World's Most Beloved Typeface". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- Linotype, Designer description.

- "The Language Whiz — Helvetica Linotype". Linotype.com. 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Linotype Releases 1100+ OpenType Fonts: Release a Significant Step Towards Format's Acceptance". Typographica.org. August 6, 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

In the Comments Section: The biggest differences are the new Greek, Cyrillic and Hebrew designs, and the presence of Arabic support based on the radically redesigned Yakout Linotype (not a perfect match for the Helvetica, but the most appropriate in the Linotype Library; this is 'core font' Arabic support: not for fine typography). There is also a large maths and symbol set in each font (not complete maths typesetting support, but more than you'll get in most fonts). The only big change in the Latin is that the whole thing has been respaced. The old Helvetica Std Type 1 and TT fonts inherited, via phototype, the unit metrics of the original hot metal type. This led to all sorts of oddities in the sidebearings, which were cleaned up during development of Helvetica Linotype. It is still quite a tightly spaced typeface by today's standards, but the spacing is now consistent. It was also re-kerned. Helvetica Linotype has also been extensively hinted for screen. -- John Hudson

- "Experimental Arabic Type". Typographica.org. Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Macmillan, Neil. An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press: 2006. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

- "Download Neue Helvetica® Arabic font family". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Linotype veröffentlicht Neue Helvetica Arabic - Design von Nadine Chahine übersetzt eine der populärsten Schriften ins Arabische

- "Helvetica now available in Thai" (World Wide Web log). Linotype. Mar 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2012-04-20.

- "Helvetica jetzt auch in Thai – Eine der beliebtesten Schriften ab sofort in neuer Sprachversion bei Linotype erhältlich" (in German). 2012-03-20.

- Wongsunkakon, Anuthin (2 March 2012). "Note on Helvetica Thai". anuthin.org. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Helvetica Thai". Linotype.

- "Manop Mai" (distribution). Anuthin + Cadson Demak. Dec 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-03-22.

- Linotype released Neue Helvetica World.

- Neue Helvetica World: the standard in sans serif design for international corporate communications!

- Neue Helvetica World

- Neue Helvetica Super Family

- Strizver, Ilene (25 November 2015). "Good Looking Helvetica at Any Size". Creative Pro. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Slimbach, Robert. "Using Acumin". Acumin microsite. Adobe Systems. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Download Neue Helvetica® eText font family". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Neue Haas Grotesk". The Font Bureau, Inc. p. Introduction.

- "Neue Haas Grotesk - Font News". Linotype.com. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Schwartzco Inc". Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Shaw, Paul (2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. pp. 204–5. ISBN 978-0300219296.

- "Neue Haas Grotesk". The Font Bureau, Inc. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- "Neue Haas Grotesk Collection". Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "Neue Haas Grotesk Specimens" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Butterick, Matthew. "Neue Haas Grotesk". Typographica. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- "Whitney rebranding". EJS. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- "Bloomberg Businessweek redesign interviews". SPD. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- "Commercial Type Vault". Commercial Type. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Ding, Frederick (8 July 2015). "New fonts in Windows 10". Frederick's Timelog. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Windows 10 font list". Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- "Windows 11 font list". Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- "Helvetica® Now". Monotype. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Mallalieu, Andy. "Monotype launches the first redesign in 35 years of the world's most ubiquitous font, Helvetica". Creative Boom. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Strizver, Ilne (3 June 2019). "Introducing Helvetica Now: a reinvented classic". Creative Pro. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- "Helvetica Now User Guide" (PDF). Monotype. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Joel, William (9 April 2019). "Behind the process of Helvetica's 21st century facelift". The Verge. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Behind the process of Helvetica's 21st century facelift". 7 April 2019.

- Downer, John. "Call It What It Is". Emigre. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Loxley, Simon (14 May 2012). "Font Wars: A Story On Rivalry Between Type Foundries". Smashing Magazine. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Devroye, Luc. "Helvetica clones". Type Design Information. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Peter Karow (6 December 2012). Font Technology: Methods and Tools. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 225–8, 235–40. ISBN 978-3-642-78505-4.

- Spiekermann, Eric. "Twitter post". Twitter. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

AG Buch war GGL’s Antwort auf Helvetica, für die Berthold keine Lizenz kriegte von Linotype.

- "AG Book Pro". Berthold. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "AG Book Rounded Pro". Berthold. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "CNN now has its own font … for some reason". NewscastStudio. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "CNN Customizes New Company-Wide Font". 2016-05-02. Archived from the original on 2016-09-11. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- "CNN Sans". Vimeo. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- "Nimbus Sans". MyFonts. URW++. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Hardwig, Florian (30 September 2013). "National Trust Tree Appeal Poster". Fonts In Use. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Freeman, Luke; Hardwig, Florian (31 July 2017). ""London's Fastest" poster campaign by Nike". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Simonson, Mark (17 June 2021). "How to Spot Arial". Mark Simonson Studio.

- Shaw, Paul. "Arial Addendum no. 3". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Shaw (& Nicholas). "Arial addendum no. 4". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Finally! Good-quality free (GPL) basic-35 PostScript Type 1 fonts" (TXT). Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- "ghostscript-fonts-std-4.0.tar.gz - GhostScript 4.0 standard fonts - AFPL license". 1996-06-28. Archived from the original (TAR.GZ) on 2011-04-24. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- "Fonts". R Cookbook. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Horton, Nicholas (19 April 2010). "Specifying fonts in graphics". SAS & R. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "TeX Gyre Heros". The LaTeX font catalogue. TeX Users Group Denmark. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- The TeX Gyre (TG) Collection of Fonts, accessed 2020-09-30.

- "GNU FreeFont - Design notes". 2009-10-04. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- LiberationFontLicense – License Agreement and Limited Product Warranty, Liberation Font Software, retrieved 2012-12-19

- LICENSE - liberation-fonts, retrieved 2012-12-19

- Mandriva Linux 2008 Release Tour, archived from the original on 2010-06-19, retrieved 2010-04-04,

integrated into Mandriva Linux 2008

- "OpenOffice.org 3.3 New Features".

- Liberation Fonts, Fedora

- Larabie, Ray. "Coolvetica". Typodermic Fonts. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Purcell, Chris (5 June 2015). "Letraset International Typeface Competition Winners 1973". Fonts in Use. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Goritsky, Roman (November 23, 2020). Gramatika: On Type Measurements, Hyphen Spacings and Other Minor Considerations. Notes from the Temporary State. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- Kupferschmid, Indra. "Finding Forma". Font Bureau. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Colizzi, Alessandro. "Forma, Dattilo, Modulo: Nebiolo's last efforts to produce a universal typeface". Paul Shaw, ed. Timeless Typography, Cambridge, Mt: Mit Press (Forthcoming). Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Colizzi, Alessandro. "Forma, Dattilo, Modulo. Nebiolo's last effort to produce a 'universal' typeface". ATypI conference 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Miklavčič, Mitja. "Forma: a typeface designed by a committee". Mitja-M. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Formula Serial". MyFonts. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Pracha Suveeranont. "มานพติก้า". ๑๐ ตัวพิมพ์ กับ ๑๐ ยุคสังคมไทย (10 Faces of Thai Type and Thai Nation) (in Thai). Thaifaces. Retrieved 22 May 2020. Originally exhibited 18–31 October 2002 at the Jamjuree Art Gallery, Chulalongkorn University, and published in Sarakadee. 17 (211). September 2002.

- Punsongserm, Rachapoom; Sunaga, Shoji; Ihara, Hisayasu (October 2018). "Roman-like Thai typefaces: Breakthrough or Regression?". Back to the Future. The Future in the Past. Conference Proceedings Book. ICDHS 10th+1 Barcelona 2018. pp. 580–585.

- Simonson, Mark. "Interview with Phil Martin". Typographica. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- Puckett, James (5 March 2012). "Helvetica Flair (photo of specimen book)". Flickr.

- "Heldustry". MyFonts. URW++. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Helserif". MyFonts. URW++. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Coles, Stephen. "Twitter post". Twitter. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

[From a Helserif ad:] "Look what happened to Helvetica. It grew wings."

- Budrick, Callie (19 October 2015). "Vintage Fonts: 35 Adverts From the Past". Print. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Winch, Andrew. "Vic Carless Obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Spencer, Tim. "Kern Your Enthusiasm: Shatter". HiLoBrow. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Lineto.com". Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "LL Unica77 (Lineto/Team'77) in use". Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- "Neue Haas Unica in use". Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Carney, Rob (6 August 2014). "Greatest fonts countdown: 92 - Chalet". CreativeBloq. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Gruppe, Sabine. "House Industries: Le Must de Chalet Font". FontBlog. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Berry, John D. (2006). Dot-font: Talking About Fonts (1st ed.). New York: Mark Batty Publisher. pp. 117–121. ISBN 0-9772827-0-8.

- VanderLans, Rudy. "It's a thin line: A Review of House Industries". Speak Up. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Larabie, Ray. "Coolvetica". Typodermic Fonts. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Tselentis, Jason (August 28, 2017). "Typodermic's Raymond Larabie Talks Type, Technology & Science Fiction". How. Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

Q: What are your most frequently downloaded free fonts? A: Coolvetica. It’s downloaded almost twice as much as the next one down the list.

- "Coolvetica". MyFonts. Typodermic. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Larabie, Ray (12 April 2019). "Coolvetica Crushed". Typodermic Fonts. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Larabie, Ray. "Movatif". Typodermic Fonts. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Larabie, Ray. "GGX88". Typodermic Fonts. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

External links

- Helvetica documentary site

- Alternatives to Helvetica: two overlapping articles by Stephen Coles at fontfeed.com (archived) and fontshop.com.

- 1962 Stempel advertisement for Breite halbfette Helvetica and Helvetica Kursiv (German)

- Fonts in Use: Helvetica, Helvetica Neue