Herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

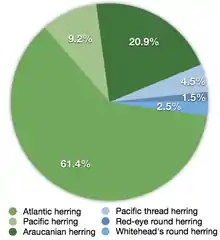

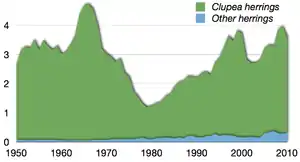

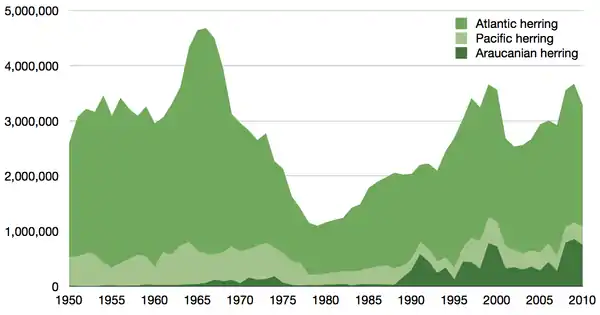

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans, including the Baltic Sea, as well as off the west coast of South America. Three species of Clupea (the type genus of the herring family Clupeidae) are recognised, and provide about 90% of all herrings captured in fisheries. The most abundant of all is the Atlantic herring, providing over half of all herring capture. Fish called herring are also found in the Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, and Bay of Bengal.

Herring played a pivotal role in the history of marine fisheries in Europe,[2] and early in the 20th century, their study was fundamental to the evolution of fisheries science.[3][4] These oily fish[5] also have a long history as an important food fish, and are often salted, smoked, or pickled.

Herring are also known as "silver darlings".[6]

Species

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

|

A number of different species, most belonging to the family Clupeidae, are commonly referred to as herrings. The origins of the term "herring" is somewhat unclear, though it may derive from the Old High German heri meaning a "host, multitude", in reference to the large schools they form.[7]

The type genus of the herring family Clupeidae is Clupea.[4] Clupea contains only two species: the Atlantic herring (the type species) found in the North Atlantic, and the Pacific herring mainly found in the North Pacific. Subspecific divisions have been suggested for both the Atlantic and Pacific herrings, but their biological basis remains unclear.

| Herrings in the genus Clupea | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| Atlantic herring | Clupea harengus Linnaeus, 1758 | 45.0 cm | 30.0 cm | 1.05 kg | 22 years | 3.23 | [8] | [9] | [10] | |

| Pacific herring | Clupea pallasii Valenciennes, 1847 | 46.0 cm | 25.0 cm | 19 years | 3.15 | [8] | [12] | [13] | Not assessed | |

In addition, a number of related species, all in the Clupeidae, are commonly referred to as herrings. The table immediately below includes those members of the family Clupeidae referred to by FishBase as herrings which have been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

| Other herrings in the family Clupeidae | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| Freshwater herrings | Toothed river herring | Clupeoides papuensis (Ramsay & Ogilby, 1886) | cm | cm | kg | years | [14] | [15] | |||

| Round herrings | Day's round herring | Dayella malabarica (Day, 1873) | cm | cm | kg | years | [17] | [18] | |||

| Dwarf round herring | Jenkinsia lamprotaenia (Gosse, 1851) | cm | cm | kg | years | [20] | [21] | ||||

| Gilchrist's round herring | Gilchristella aestuaria (Gilchrist, 1913 | cm | cm | kg | years | [23] | [24] | ||||

| Little-eye round herring | Jenkinsia majua Whitehead, 1963 | cm | cm | kg | years | [26] | [27] | ||||

| Red-eye round herring | Etrumeus teres (De Kay, 1842) | 33 cm | 25 cm | kg | years | [29] | [30] | [31] | Not assessed | ||

| Two-finned round herring | Spratellomorpha bianalis (Bertin, 1940) | 4.5 cm | cm | kg | years | 3.11 | [32] | [33] | |||

| Whitehead's round herring | Etrumeus whiteheadi (Wongratana, 1983) | 20 cm | cm | kg | years | 3.4 | [35] | [36] | [37] | ||

| Venezuelan herring | Jenkinsia parvula Cervigón and Velasquez, 1978 | cm | cm | kg | years | [39] | [40] | ||||

| Thread herrings | Galapagos thread herring | Opisthonema berlangai (Günther, 1867) | 26 cm | 18 cm | kg | years | 3.27 | [42] | [43] | ||

| Middling thread herring | Opisthonema medirastre Berry & Barrett, 1963 | cm | cm | kg | years | [45] | [46] | ||||

| Pacific thread herring | Opisthonema libertate (Günther, 1867) | 30 cm | 22 cm | kg | years | [48] | [49] | [43] | |||

| Slender thread herring | Opisthonema bulleri (Regan, 1904) | cm | cm | kg | years | [51] | [52] | ||||

| Other | Araucanian herring | Strangomera bentincki (Norman, 1936) | 28.4 cm | cm | kg | years | 2.69 | [54] | [55] | [56] | Not assessed |

| Blackstripe herring | Lile nigrofasciata Castro-Aguirre Ruiz-Campos and Balart, 2002 | cm | cm | kg | years | [57] | [58] | ||||

| Denticle herring | Denticeps clupeoides Clausen, 1959 | cm | cm | kg | years | [60] | [61] | ||||

| Dogtooth herring | Chirocentrodon bleekerianus (Poey, 1867) | cm | cm | kg | years | [63] | [64] | ||||

| Graceful herring | Lile gracilis Castro-Aguirre and Vivero, 1990 | cm | cm | kg | years | [66] | [67] | ||||

| Pacific Flatiron herring | Harengula thrissina (Jordan and Gilbert, 1882) | cm | cm | kg | years | [69] | [70] | ||||

| Sanaga pygmy herring | Thrattidion noctivagus Roberts, 1972 | cm | cm | kg | years | [72] | [73] | ||||

| Silver-stripe round herring | Spratelloides gracilis (Temminck & Schlegel, 1846) | 10.5 cm | cm | kg | years | 3.0 | [75] | [76] | Not assessed | ||

| Striped herring | Lile stolifera (Jordan & Gilbert, 1882) | cm | cm | kg | years | [77] | [78] | ||||

| West African pygmy herring | Sierrathrissa leonensis Thys van den Audenaerde, 1969 | cm | cm | kg | years | [80] | [81] | ||||

Also, a number of other species are called herrings, which may be related to clupeids or just share some characteristics of herrings (such as the lake herring, which is a salmonid). Just which of these species are called herrings can vary with locality, so what might be called a herring in one locality might be called something else in another locality. Some examples:

| Other fishes called herring | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status | |

| Longfin herring | Bigeyed longfin herring | Opisthopterus macrops (Günther, 1867) | cm | cm | kg | years | [83] | [84] | |||

| Dove's longfin herring | Opisthopterus dovii (Günther 1868) | cm | cm | kg | years | [86] | [87] | ||||

| Hatchet herring | Ilisha fuerthii (Steindachner, 1875) | cm | cm | kg | years | [89] | [90] | ||||

| Panama longfin herring | Odontognathus panamensis (Steindachner, 1876) | cm | cm | kg | years | [92] | [93] | ||||

| Tropical longfin herring | Neoopisthopterus tropicus (Hildebrand 1946) | cm | cm | kg | years | [95] | [96] | ||||

| Vaqueira longfin herring | Opisthopterus effulgens (Regan 1903) | cm | cm | kg | years | [98] | [99] | ||||

| Equatorial longfin herring | Opisthopterus equatorialis Hildebrand, 1946 | cm | cm | kg | years | [101] | [102] | ||||

| Wolf herring | Dorab wolf-herring | Chirocentrus dorab (Forsskål, 1775) | 100 cm | 60 cm | kg | years | 4.50 | [104] | [105] | [106] | Not assessed |

| Whitefin wolf-herring | Chirocentrus nudus Swainson, 1839 | 100 cm | cm | 0.41 kg | years | 4.19 | [107] | [108] | Not assessed | ||

| Freshwater whitefish | Lake herring (cisco) | Coregonus artedi Lesueur, 1818 | cm | cm | kg | years | [109] | [110] | Not assessed | ||

Characteristics

The species of Clupea belong to the larger family Clupeidae (herrings, shads, sardines, menhadens), which comprises some 200 species that share similar features. These silvery-coloured fish have a single dorsal fin, which is soft, without spines. They have no lateral line and have a protruding lower jaw. Their size varies between subspecies: the Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras) is small, 14 to 18 cm; the proper Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus harengus) can grow to about 46 cm (18 in) and weigh up 700 g (1.5 lb); and Pacific herring grow to about 38 cm (15 in).

Lifecycle

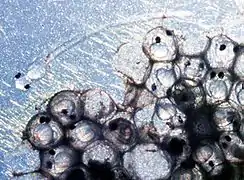

At least one stock of Atlantic herring spawns in every month of the year. Each spawns at a different time and place (spring, summer, autumn, and winter herrings). Greenland populations spawn in 0–5 metres (0–16 feet) of water, while North Sea (bank) herrings spawn at down to 200 m (660 ft) in autumn. Eggs are laid on the sea bed, on rock, stones, gravel, sand or beds of algae. Females may deposit from 20,000 to 40,000 eggs, according to age and size, averaging about 30,000. In sexually mature herring, the genital organs grow before spawning, reaching about one-fifth of its total weight.

The eggs sink to the bottom, where they stick in layers or clumps to gravel, seaweed, or stones, by means of their mucous coating, or to any other objects on which they chance to settle.

If the egg layers are too thick they suffer from oxygen depletion and often die, entangled in a maze of mucus. They need substantial water microturbulence, generally provided by wave action or coastal currents. Survival is highest in crevices and behind solid structures, because predators feast on openly exposed eggs. The individual eggs are 1 to 1.4 mm (3⁄64 to 1⁄16 in) in diameter, depending on the size of the parent fish and also on the local race. Incubation time is about 40 days at 3 °C (37 °F), 15 days at 7 °C (45 °F), or 11 days at 10 °C (50 °F). Eggs die at temperatures above 19 °C (66 °F).

The larvae are 5 to 6 mm (3⁄16 to 1⁄4 in) long at hatching, with a small yolk sac that is absorbed by the time the larvae reach 10 mm (13⁄32 in). Only the eyes are well pigmented. The rest of the body is nearly transparent, virtually invisible under water and in natural lighting conditions.

The dorsal fin forms at 15 to 17 mm (19⁄32 to 21⁄32 in), the anal fin at about 30 mm (1+3⁄16 in)—the ventral fins are visible and the tail becomes well forked at 30 to 35 mm (1+3⁄8 in)— at about 40 mm (1+9⁄16 in), the larva begins to look like a herring.

Herring larvae are very slender and can easily be distinguished from all other young fish of their range by the location of the vent, which lies close to the base of the tail; however, distinguishing clupeoids one from another in their early stages requires critical examination, especially telling herring from sprats.

At one year, they are about 10 cm (4 in) long, and they first spawn at three years.

Ecology

Prey

Herrings consume copepods, arrow worms, pelagic amphipods, mysids, and krill in the pelagic zone. Conversely, they are a central prey item or forage fish for higher trophic levels. The reasons for this success are still enigmatic; one speculation attributes their dominance to the huge, extremely fast cruising schools they inhabit.

Herring feed on phytoplankton, and as they mature, they start to consume larger organisms. They also feed on zooplankton, tiny animals found in oceanic surface waters, and small fish and fish larvae. Copepods and other tiny crustaceans are the most common zooplankton eaten by herring. During daylight, herring stay in the safety of deep water, feeding at the surface only at night when the chance of being seen by predators is less. They swim along with their mouths open, filtering the plankton from the water as it passes through their gills. Young herring mostly hunt copepods individually, by means of "particulate feeding" or "raptorial feeding",[111] a feeding method also used by adult herring on larger prey items like krill. If prey concentrations reach very high levels, as in microlayers, at fronts, or directly below the surface, herring become filter feeders, driving several meters forward with wide open mouth and far expanded opercula, then closing and cleaning the gill rakers for a few milliseconds.

Copepods, the primary zooplankton, are a major item on the forage fish menu. Copepods are typically 1–2 mm (1⁄32–3⁄32 in) long, with a teardrop-shaped body. Some scientists say they form the largest animal biomass on the planet.[112] Copepods are very alert and evasive. They have large antennae (see photo below left). When they spread their antennae, they can sense the pressure wave from an approaching fish and jump with great speed over a few centimetres. If copepod concentrations reach high levels, schooling herrings adopt a method called ram feeding. In the photo below, herring ram feed on a school of copepods. They swim with their mouths wide open and their operculae fully expanded.

The fish swim in a grid where the distance between them is the same as the jump length of their prey, as indicated in the animation above right. In the animation, juvenile herring hunt the copepods in this synchronised way. The copepods sense with their antennae the pressure wave of an approaching herring and react with a fast escape jump. The length of the jump is fairly constant. The fish align themselves in a grid with this characteristic jump length. A copepod can dart about 80 times before it tires. After a jump, it takes it 60 milliseconds to spread its antennae again, and this time delay becomes its undoing, as the almost endless stream of herring allows a herring to eventually snap up the copepod. A single juvenile herring could never catch a large copepod.[111]

Other pelagic prey eaten by herring includes fish eggs, larval snails, diatoms by herring larvae below 20 mm (13⁄16 in), tintinnids by larvae below 45 mm (1+3⁄4 in), molluscan larvae, menhaden larvae, krill, mysids, smaller fishes, pteropods, annelids, Calanus spp., Centropagidae, and Meganyctiphanes norvegica.

Herrings, along with Atlantic cod and sprat, are the most important commercial species to humans in the Baltic Sea.[113] The analysis of the stomach contents of these fish indicate Atlantic cod is the top predator, preying on the herring and sprat.[113][114] Sprat are competitive with herring for the same food resources. This is evident in the two species' vertical migration in the Baltic Sea, where they compete for the limited zooplankton available and necessary for their survival.[115] Sprat are highly selective in their diet and eat only zooplankton, while herring are more eclectic, adjusting their diet as they grow in size.[115] In the Baltic, copepods of the genus Acartia can be present in large numbers. However, they are small in size with a high escape response, so herring and sprat avoid trying to catch them. These copepods also tend to dwell more in surface waters, whereas herring and sprat, especially during the day, tend to dwell in deeper waters.[115]

Predators

Predators of herring include seabirds, marine mammals such as dolphins, porpoises, whales, seals, and sea lions, predatory fish such as sharks, billfish, tuna, salmon, striped bass, cod, and halibut. Fishermen also catch and eat herring.

The predators often cooperate in groups, using different techniques to panic or herd a school of herring into a tight bait ball. Different predatory species then use different techniques to pick the fish off in the bait ball. The sailfish raises its sail to make it appear much larger. Swordfish charge at high speed through the bait balls, slashing with their swords to kill or stun prey. They then turn and return to consume their "catch". Thresher sharks use their long tails to stun the shoaling fish. These sharks compact their prey school by swimming around them and splashing the water with their tails, often in pairs or small groups. They then strike them sharply with the upper lobe of their tails to stun them.[116] Spinner sharks charge vertically through the school, spinning on their axes with their mouths open and snapping all around. The sharks' momentum at the end of these spiraling runs often carries them into the air.[117][118]

Some whales lunge feed on bait balls.[119] Lunge feeding is an extreme feeding method, where the whale accelerates from below the bait ball to a high velocity and then opens its mouth to a large gape angle. This generates the water pressure required to expand its mouth and engulf and filter a huge amount of water and fish. Lunge feeding by rorquals, a family of huge baleen whales that includes the blue whale, is said to be the largest biomechanical event on Earth.[120]

| More images | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sailfish herd herring schools with their sails  Swordfish slash at herrings with their swords  Thresher shark strike them with their tails  Spinner shark spin on their axis, snapping herrings as they go  Dolphins can hunt herring in groups

| ||||||

Fisheries

Adult herring are harvested for their flesh and eggs, and they are often used as baitfish. The trade in herring is an important sector of many national economies. In Europe, the fish has been called the "silver of the sea", and its trade has been so significant to many countries that it has been regarded as the most commercially important fishery in history.[121]

.jpeg.webp)

Environmental Defense have suggested that the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) fishery is an environmentally responsible fishery.[122]

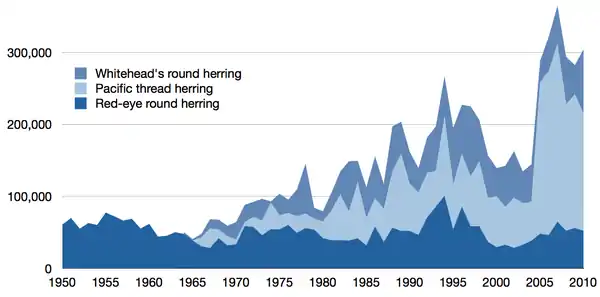

| Detailed time series |

|---|

As food

Herring has been a staple food source since at least 3000 BC. The fish is served numerous ways, and many regional recipes are used: eaten raw, fermented, pickled, or cured by other techniques, such as being smoked as kippers.

Herring are very high in the long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA.[123] They are a source of vitamin D.[124]

Water pollution influences the amount of herring that may be safely consumed. For example, large Baltic herring slightly exceeds recommended limits with respect to PCB and dioxin, although some sources point out that the cancer-reducing effect of omega-3 fatty acids is statistically stronger than the carcinogenic effect of PCBs and dioxins.[125] The contaminant levels depend on the age of the fish which can be inferred from their size. Baltic herrings larger than 17 cm (6.7 in) may be eaten twice a month, while herrings smaller than 17 cm can be eaten freely.[126] Mercury in fish also influences the amount of fish that women who are pregnant or planning to be pregnant within the next one or two years may safely eat.

History

The herring has played a highly significant role in history both socially and economically. During the Middle Ages, herring prompted the founding of Great Yarmouth, Amsterdam, and Copenhagen.[127] In 1274, while on his deathbed at the monastery of Fossanova (south of Rome, Italy), when encouraged to eat something to regain his strength, Thomas Aquinas asked for fresh herring.[128]

| Historical images |

|---|

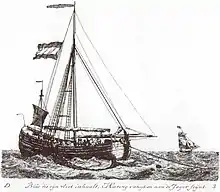

Paintings  Still life with herring and stoneware jug, Georg Flegel, c. 1600  Still life with a glass of beer and smoked herring on a plate, Pieter Claesz 1636  Still Life with smoked herrings on yellow paper, Van Gogh 1889 Herring boats  The herring buss 1789  Norse herring boat  Reaper, typical of the herring boats that used to operate in Scotland during the early twentieth century  The last surviving steam drifter of the Great Yarmouth herring fleet, Norfolk. Drifters were designed to catch herrings in a long drift net. General history  Herring monger, ca 1500  Medieval herring fishing in Scania, 1555 _-_Amsterdam.PNG.webp) 17th century herring factory in Amsterdam  Processing river herrings[129]  The Dutch herring fleet, c. 1700  Barrels for storing salted herring, c. 1465 at the archaeological site of Walraversijde, Belgium  Japanese Pacific herring fisherman's house in the historic village of Hokkaidō, Sapporo  Press for extracting oil from herrings in the historic village  "Last Tuesday se'nnight three men met at the Crown Inn, Everley, and for a trifling wager, ate 6o red herrings, with three half-gallon loaves, and drank six gallons of beer"[130] – 1792 |

See also

- Herringbone pattern

References

Citations

- Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets Archived 2009-05-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Cushing, David H (1975) Marine ecology and fisheries Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09911-0.

- Went, AEJ (1972) "The History of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biology, 73: 351–360.doi:10.1017/S0080455X0000240X

- Pauly, Daniel (2004) Darwin's Fishes: An Encyclopedia of Ichthyology, Ecology, and Evolution Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Page 109, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82777-5.

- "What's an oily fish?". Food Standards Agency. 2004-06-24. Archived from the original on 2010-12-10.

- "Here be herrings: the return of the silver darlings". The Guardian. 2014-11-12.

- Herring Archived 2015-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Online Etymology Dictionary, Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Clupea harengus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Clupea harengus (Linnaeus, 1758) Archived 2012-01-04 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Clupea harengus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Herdson, D.; Priede, I.G. (2010). "Clupea harengus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T155123A4717767. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T155123A4717767.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Clupea pallasii (Valenciennes, 1847) Archived 2011-12-06 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Clupea pallasii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Clupeoides papuensis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Clupeoides papuensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2019). "Clupeoides papuensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T4984A102881251. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T4984A102881251.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Dayella malabarica" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Dayella malabarica". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Mohd Arshaad, W.; Munroe, T.A.; Gaughan, D.; Raghavan, R.; Ali, A. (2017). "Dayella malabarica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T172314A60601652. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T172314A60601652.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Jenkinsia lamprotaenia" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Jenkinsia lamprotaenia". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Munroe, T.A.; Di Dario, F. (2020). "Jenkinsia lamprotaenia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T154793A18130945. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T154793A18130945.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Gilchristella aestuaria" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Gilchristella aestuaria". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Bills, R. (2007). "Gilchristella aestuaria". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T63245A12644478. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T63245A12644478.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Jenkinsia majua" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Jenkinsia majua". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F.; Munroe, T.A.; Grijalba Bendeck, L.; Aiken, K.A. (2020). "Jenkinsia majua". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T155253A46930957. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T155253A46930957.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Etrumeus teres" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Etrumeus teres (Norman, 1936) Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Etrumeus teres". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Spratellomorpha bianalis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Spratellomorpha bianalis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Sparks, J.S. (2016). "Spratellomorpha bianalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T44664A96229991. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T44664A96229991.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Etrumeus whiteheadi" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Etrumeus whiteheadi (Wongratana, 1983) Archived 2014-08-13 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Etrumeus whiteheadi". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Munroe, T.A.; Di Dario, F. (2020). "Etrumeus whiteheadi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T154968A15530233. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T154968A15530233.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Jenkinsia parvula" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Jenkinsia parvula". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F.; Munroe, T.A.; Aiken, K.A.; Brown, J.; Grijalba Bendeck, L. (2017). "Jenkinsia parvula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T10939A86372523. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T10939A86372523.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthonema berlangai" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthonema libertate". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthonema berlangai". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183720A102896673. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183720A102896673.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthonema medirastre" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthonema medirastre". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthonema medirastre". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183235A102897018. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183235A102897018.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthonema libertate" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Opisthonema libertate (Günther, 1867) Archived 2013-04-14 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- Munroe, T.A.; Di Dario, F. (2020). "Etrumeus whiteheadi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T154968A15530233. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T154968A15530233.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthonema bulleri" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthonema bulleri". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthonema bulleri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183910A102896852. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183910A102896852.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Clupea bentincki" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Clupea bentincki (Norman, 1936) Archived 2012-07-29 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Clupea bentincki". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Lile nigrofasciata" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Lile nigrofasciata". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Lile nigrofasciata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183437A102896150. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183437A102896150.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Denticeps clupeoides" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Denticeps clupeoides". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Lalèyè, P. (2020). "Denticeps clupeoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T182459A134946905. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T182459A134946905.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Chirocentrodon bleekerianus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Chirocentrodon bleekerianus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F.; Williams, J.T.; Nanola, C.; Arceo, H.; Acosta, A.K.M.; Palla, H.P.; Muallil, R.; Ram, M.; Beresford, A.; Collen, B.; Richman, N.; Chenery, A. (2017). "Chirocentrodon bleekerianus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T155181A46929727. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T155181A46929727.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Lile gracilis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Lile gracilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Iwamoto, T.; Eschmeyer, W.; Smith-Vaniz, B. (2010). "Lile gracilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T183277A8085306. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T183277A8085306.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Harengula thrissina" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Harengula thrissina". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Iwamoto, T.; Eschmeyer, W.; Smith-Vaniz, B. (2010). "Harengula thrissina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T183931A8201850. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T183931A8201850.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Thrattidion noctivagus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Thrattidion noctivagus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2018). "Thrattidion noctivagus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T182664A143864630. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T182664A143864630.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Spratelloides gracilis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Spratelloides gracilis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Lile stolifera" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Lile stolifera". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Iwamoto, T.; Eschmeyer, W. (2010). "Lile stolifera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T183336A8095864. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T183336A8095864.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Sierrathrissa leonensis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Sierrathrissa leonensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Diouf, K.; Moelants, T.; Olaosebikan, B.D. (2020). "Sierrathrissa leonensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T181746A134911200. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T181746A134911200.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthopterus macrops" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthopterus macrops". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthopterus macrops". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183414A102907138. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183414A102907138.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthonema dovii" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthopterus dovii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthopterus dovii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183922A102906567. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183922A102906567.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Ilisha fuerthii" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Ilisha fuerthii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F.; Williams, J.T.; Nanola, C.; Muallil, R.; Palla, H.P.; Arceo, H.; Acosta, A.K.M. (2017). "Ilisha fuerthii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T183757A102905793. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T183757A102905793.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Odontognathus panamensis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Odontognathus panamensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Odontognathus panamensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183387A102906414. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183387A102906414.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Neoopisthopterus tropicus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Neoopisthopterus tropicus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F.; Williams, J.T.; Nanola, C.; Palla, H.P.; Arceo, H.; Acosta, A.K.M.; Muallil, R. (2017). "Neoopisthopterus tropicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T183217A102906158. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T183217A102906158.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthopterus effulgens" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthopterus effulgens". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2018). "Opisthopterus effulgens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T183670A143831937. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T183670A143831937.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Opisthopterus equatorialis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Opisthopterus equatorialis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Di Dario, F. (2020). "Opisthopterus equatorialis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T183876A102907002. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T183876A102907002.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Chirocentrus dorab" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- Chirocentrus dorab (Forsskål, 1775) Archived 2015-04-14 at the Wayback Machine FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- "Chirocentrus dorab". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Chirocentrus nudus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Chirocentrus nudus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2012). "Coregonus artedi" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- "Coregonus artedi". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Kils U (1992) The ATOLL Laboratory and other Instruments Developed at Kiel U.S. GLOBEC News, Technology Forum Number 8: 6–9.

- Biology of Copepods Archived 2009-01-01 at the Wayback Machine at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg

- Friedrich W. Köster, et al. "Developing Baltic Cod Recruitment Models. I. Resolving Spatial And Temporal Dynamics Of Spawning Stock And Recruitment For Cod, Herring, And Sprat." Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences 58.8 (2001): 1516. Academic Search Premier. Web. 21 Nov. 2011. p. 1516.

- Maris Plikshs, et al. "Developing Baltic Cod Recruitment Models. I. Resolving Spatial And Temporal Dynamics Of Spawning Stock And Recruitment For Cod, Herring, And Sprat." Canadian Journal of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences 58.8 (2001): 1516. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Nov. 2011, p.1517

- Casini, Michele, Cardinale, Massimiliano, and Arrheni, Fredrik. "Feeding preferences of herring (Clupea harengus) and sprat (Sprattus sprattus) in the southern Baltic Sea." ICES Journal of Marine Science, 61 (2004): 1267–1277. Science Direct. Web. 22 November 2011. p. 1268.

- Seitz, J.C. Pelagic Thresher Archived 2011-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved on December 22, 2008.

- Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation. pp. 466–468. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- "Carcharhinus brevipinna, Spinner Shark". MarineBio.org. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- Reeves RR, Stewart BS, Clapham PJ and Powell J A (2002) National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World Archived 2016-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Chanticleer Press. ISBN 9780375411410.

- Potvin J and Goldbogen JA (2009) "Passive versus active engulfment: verdict from trajectory simulations of lunge-feeding fin whales Balaenoptera physalus Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine J. R. Soc. Interface, 6(40): 1005–1025. doi:10.1098/rsif.2008.0492

- Herring Archived 2010-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, from Census of Marine Life Archived 2010-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

- Eco-Best Fish - Safe for the environment Archived 2008-03-13 at the Wayback Machine, from Environmental Defense Fund Archived 2010-07-24 at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

- Cardiovascular Benefits Of Omega-3 Fatty Acids Reviewed Archived 2010-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Aro, Tarja L.; Larmo, Petra S.; Bäckman, Christina H.; Kallio, Heikki P.; Tahvonen, Raija L. (2005-03-01). "Fatty Acids and Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Salted Herring (Clupea harengus) Products". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (5): 1482–1488. doi:10.1021/jf0401221. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 15740028.

- Risks and benefits are clarified by food risk assessment – Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Archived 2007-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Dietary advice on fish consumption – Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira Archived 2010-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Hunt, Kathy (2017). Herring A Global History. Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-78023-831-9.

- Process of Canonization of St. Thomas Aquinas, Testimony of Br. Peter of Montesangiovanni

- River herring Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine NEFSC, NOAA. Updated December 2006.

- Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 9 January 1792.

Sources

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). Species of Clupea in FishBase. January 2006 version.

- Dewhurst HW (1834) Clupea harengis or the common herring In: The Natural History of the Order Cetacea, Oxford University. Pages 232–246.

- Geffen, Audrey J (2009) Advances in herring biology: from simple to complex, coping with plasticity and adaptability: ICES Journal of Marine Science, 66 (8): 1688–1695.

- Gilpen JB (1867) "On the common herring (Clupea elongata)" Proceedings and Transactions of the Nova-Scotian Institute of Natural Science, 1 (1): 4–11.

- O'Clair, Rita M. and O'Clair, Charles E., "Pacific herring," Southeast Alaska's Rocky Shores: Animals. pg. 343–346. Plant Press: Auke Bay, Alaska (1998). ISBN 0-9664245-0-6

- Stephenson RL (2001) The role of herring investigations in shaping fisheries science In F. Funk, J. Blackburn, D. Hay, A.J. Paul, R. Stephen- son, R. Toresen, and D. Witherell (eds.) Herrings: Expectations for a New Millennium, Alaska Sea Grant College Program. AK-SG-01-04. pp. 1–20. ISBN 1-56612-070-5.

- Stephenson, R. L., Melvin, G. D., and Power, M. J. (2009) "Population integrity and connectivity in Northwest Atlantic herring: a review of assumptions and evidence" ICES Journal of Marine Science, 66: 1733–1739.

- Whitehead PJP, Nelson GJ and Wongratana T (1988) FAO species catalogue, volume 2: Clupeoid Fishes of the World, Suborder Clupeoidei FAO Fisheries Synopsis 125, Rome. ISBN 92-5-102340-9. Download ZIP (16 MB)

Further reading

- Baltic Fisheries Cooperation Committee (1995) Utilization and Marketing of Baltic Herring Nordic Council of Ministers. ISBN 9789291207749.

- Bigelow HB and Schroeder WC (1953) Fishes of the Gulf of Maine Pages 88–100, Fishery Bulletin 74(53), NOAA. pdf version

- Dodd JS (1752) An essay toward a natural history of the herring Original from the New York Public Library.

- Mitchell JM (1864) The herring: its natural history and national importance Edmonston and Douglas. Original from the University of Wisconsin.

- Postan MM, Miller E and Habakkuk HJ (1987) The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and industry in the Middle Ages Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521087094.

- Poulsen B (2008) Dutch Herring: An Environmental History, C. 1600–1860 Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789052603049.

- Samuel AM (1918) The herring: its effect on the history of Britain J. Murray. Original from the University of Michigan.

- Stephenson F (2007) Herring Fishermen: Images of an Eastern North Carolina Tradition The History Press. ISBN 9781596292697.

- Waters B (1809) Letters upon the subject of the herring fishery: addressed to the secretary of the Honourable the Board for the Herring Fishery at Edinburgh, to which is added, a petition to the lords of the treasury on the same subject Original from Harvard University.

External links

- Herring "communicate" by flatulence from National Geographic (2003)

- Atlantic Herring from the Gulf of Maine Research Institute

- Nutrition Facts for Herring

- Prospecting herring waste – from ScienceNordic

- PNAS Population-scale sequencing reveals genetic differentiation due to local adaptation in Atlantic herring. Archived 2021-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

.png.webp)