Hoysala literature

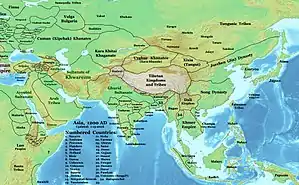

Hoysala literature is the large body of literature in the Kannada and Sanskrit languages produced by the Hoysala Empire (1025–1343) in what is now southern India.[1] The empire was established by Nripa Kama II, came into political prominence during the rule of King Vishnuvardhana (1108–1152),[2] and declined gradually after its defeat by the Khalji dynasty invaders in 1311.[3]

Kannada literature during this period consisted of writings relating to the socio-religious developments of the Jain and Veerashaiva faiths, and to a lesser extent that of the Vaishnava faith. The earliest well-known brahmin writers in Kannada were from the Hoysala court.[4] While most of the courtly textual production was in Kannada,[5] an important corpus of monastic Vaishnava literature relating to Dvaita (dualistic) philosophy was written by the renowned philosopher Madhvacharya in Sanskrit.[6]

Writing Kannada literature in native metres was first popularised by the court poets. These metres were the sangatya, compositions sung to the accompaniment of a musical instrument; shatpadi, six-line verses; ragale, lyrical compositions in blank verse; and tripadi, three-line verses.[7] However, Jain writers continued to use the traditional champu, composed of prose and verse.[8] Important literary contributions in Kannada were made not only by court poets but also by noblemen, commanders, ministers, ascetics and saints associated with monasteries.[9]

Kannada writings

Overview

| Noted Kannada poets and writers in Hoysala Empire (1100-1343 CE) | |

| Nagachandra | 1105 |

| Kanti | 1108 |

| Rajaditya | 12th. c |

| Harihara | 1160–1200 |

| Udayaditya | 1150 |

| Vritta Vilasa | 1160 |

| Kereya Padmarasa | 1165 |

| Nemichandra | 1170 |

| Sumanobana | 1175 |

| Rudrabhatta | 1180 |

| Aggala | 1189 |

| Palkuriki Somanatha | 1195 |

| Sujanottamsa(Boppana) | 1180 |

| Kavi Kama | 12th c. |

| Devakavi | 1200 |

| Raghavanka | 1200–1225 |

| Bhanduvarma | 1200 |

| Balachandra Kavi | 1204 |

| Parsva Pandita | 1205 |

| Maghanandycharya | 1209 |

| Janna | 1209–1230 |

| Puligere Somanatha | 13th c. |

| Hastimalla | 13th c. |

| Chandrama | 13th c. |

| Somaraja | 1222 |

| Gunavarma II | 1235 |

| Polalvadandanatha | 1224 |

| Andayya | 1217–1235 |

| Sisumayana | 1232 |

| Mallikarjuna | 1245 |

| Naraharitirtha | 1281 |

| Kumara Padmarasa | 13th c. |

| Mahabala Kavi | 1254 |

| Kesiraja | 1260 |

| Kumudendu | 1275 |

| Nachiraja | 1300 |

| Ratta Kavi | 1300 |

| Nagaraja | 1331 |

| Noted Kannada poets and writers in the Seuna Yadava Kingdom | |

| Kamalabhava | 1180 |

| Achanna | 1198 |

| Amugideva | 1220 |

| Chaundarasa | 1300 |

Beginning with the 12th century, important socio-political changes took place in the Deccan, south of the Krishna river. During this period, the Hoysalas, native Kannadigas from the Malnad region (hill country in modern Karnataka) were on the ascendant as a political power.[10][11][12][13] They are known to have existed as chieftains from the mid-10th century when they distinguished themselves as subordinates of the Western Chalukyas of Kalyani.[14] In 1116, Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana defeated the Cholas of Tanjore and annexed Gangavadi (parts of modern southern Karnataka),[15] thus bringing the region back under native rule. In the following decades, with the waning of the Chalukya power, the Hoysalas proclaimed independence and grew into one of the most powerful ruling families of southern India.[2][16] Consequently, literature in Kannada, the local language, flourished in the Hoysala empire.[17] This literature can be broadly subdivided as follows: works dominated by the themes of Jain writings,[8] contrasting works by Veerashaiva writers not belonging to the vachana poetic tradition,[18] rebuttals to Shaiva writings from Jain writers,[19] early brahminical works (Vaishnava),[20][21] works from the birth of the Bhakti (devotional) movement in the Kannada-speaking region, writings on secular topics,[22] and the first writings in native metres (ragale, sangatya and shatpadi).[23][24][25]

As in earlier centuries, Jain authors wrote about tirthankars (saints), princes and other personages important to the Jain religion. Jain versions of the Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and Bhagavata (tales of Hindu god Krishna) were also written.[26][27] According to R. Narasimhacharya, a noted scholar on Kannada literature, more Jain writers wrote in Kannada than in any other Dravidian language during the "Augustan age" of Kannada literature, from the earliest known works to the 12th century.[28] The Veerashaiva writers, devotees of the Hindu god Shiva, wrote about his 25 forms in their expositions of Shaivism. Vaishnava authors wrote treatments of the Hindu epics, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Bhagavata.[29] Breaking away from the old Jain tradition of using the champu form for writing Kannada literature, Harihara penned poems in the ragale metre in Siva-ganada-ragalegalu (1160). His nephew Raghavanka established the shatpadi tradition by writing a unique version of the story of King Harishchandra in Harishchandra Kavya (1200). Sisumayana introduced the sangatya metre in his Anjanacharita and Tripuradahana (1235).[30][31] However, some scholars continued to employ Sanskritic genres such as champu (Ramachandra Charitapurana),[32] shataka (100 verse compositions, Pampa sataka)[18] and ashtaka (eight line verse compositions, Mudige ashtaka).[33]

The exact beginnings of the haridasa movement in the Kannada-speaking region have been disputed. Belur Keshavadasa, a noted Harikatha scholar, claimed in his book Karnataka Bhaktavijaya that the movement was inspired by saint Achalananda Dasa of Turvekere (in the modern Tumkur district) in the 9th century.[34] However, neither the language used in Achalananda Dasa's compositions nor the discovery of a composition with the pen name "Achalanada Vitthala", which mentions the 13th-century philosopher Madhvacharya, lends support to the 9th-century theory. Naraharitirtha (1281), one of earliest disciples of Madhvacharya, is therefore considered the earliest haridasa to write Vaishnava compositions in Kannada.[35] Secular topics were popular and included treatises on poetry (Sringararatnakara) and writings on natural sciences (Rattasutra), mathematics (Vyavaharaganita), fiction (Lilavati), grammar (Shabdamanidarpana), rhetoric (Udayadityalankara) and others.[8][22][26][36]

Important contributions were made by some prominent literary families. One Jain family produced several authors, including Mallikarjuna, the noted anthologist (1245); his brother-in-law Janna (1209), the court poet of King Veera Ballala II; Mallikarjuna's son Keshiraja (1260), considered by D. R. Nagaraj, a scholar on literary cultures in history, to be the greatest theorist of Kannada grammar; and Sumanobana, who was in the court of King Narasimha I and was the maternal grandfather of Keshiraja.[37][38] Harihara (1160) and his nephew Raghavanka (1200), poets who set the trend for using native metres, came from a Shaiva family (devotees of the god Shiva).[37]

The support of the Hoysala rulers for the Kannada language was strong, and this is seen even in their epigraphs, often written in polished and poetic language, rather than prose, with illustrations of floral designs in the margins.[39] In addition to the Hoysala patronage, royal support was enjoyed by Kannada poets and writers during this period in the courts of neighbouring kingdoms of the western Deccan. The Western Chalukyas, the Southern Kalachuris, the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri and the Silharas of Kolhapur are some of the ruling families who enthusiastically used Kannada in inscriptions and promoted its literature.[39][40][41][42]

Writers bilingual in Kannada and Telugu gained popularity which caused interaction between the two languages, a trend that continued into modern times. The Veerashiva canon of the Kannada language was translated or adapted into Telugu from this time period.[43] Palkuriki Somanatha (1195), a devotee of social reformer Basavanna, is the most well-known of these bilingual poets. The Chola chieftain Nannechoda (c. 1150) used many Kannada words in his Telugu writings.[44] After the decline of the Hoysala empire, the Vijayanagara empire kings further supported writers in both languages. In 1369, inspired by Palkuriki Somanatha, Bhima Kavi translated the Telugu Basavapurana to Kannada,[45] and King Deva Raya II (c. 1425) had Chamarasa's landmark writing Prabhulingalile translated into Telugu and Tamil.[46] Many Veerashaiva writers in the court of the 17th century Kingdom of Mysore were multilingual in Kannada, Telugu and Sanskrit while the Srivaishnava (a sect of Vaishnavism) Kannada writers of the court were in competition with the Telugu and Sanskrit writers.[47]

Information from contemporary records regarding several writers from this period whose works are considered lost include: Maghanandi (probable author of Rama Kathe and guru of Kamalabhava of 1235), Srutakirti (guru of Aggala, and author of Raghava Pandaviya and possibly a Jina-stuti, 1170), Sambha Varma (mentioned by Nagavarma of 1145),[48] Vira Nandi (Chandraprabha Kavyamala, 1175),[49] Dharani Pandita (Bijjala raya Charita and Varangana Charita),[50] Amrita Nandi (Dhanvantari Nighantu), Vidyanatha (Prataparudriya), Ganeshvara (Sahitya Sanjivana),[51] Harabhakta, a Veerashaiva mendicant (Vedabhashya, 1300), and Siva Kavi (author of Basava Purana in 1330).[52]

Jain epics

During the early 12th-century ascendancy of the Hoysalas, the kings of the dynasty entertained imperial ambitions.[16] King Vishnuvardhana wanted to perform Vedic sacrifices befitting an emperor, and surpass his overlords, the Western Chalukyas, in military and architectural achievements. This led to his conversion from Jainism to Vaishnavism. Around the same time, the well-known philosopher Ramanujacharya sought refuge from the Cholas in Hoysala territory and popularised the Sri Vaishnava faith, a sect of Hindu Vaishnavism. Although Jains continued to dominate culturally in what is now the southern Karnataka region for a while, these social changes would later contribute to the decline of Jain literary output.[1][53] The growing political clout of the Hoysalas attracted many bards and scholars to their court, who in turn wrote panegyrics on their patrons.[54]

Nagachandra, a scholar and the builder of the Mallinatha Jinalaya (a Jain temple in honour of the 19th Jain tirthankar, Mallinatha, in Bijapur, Karnataka), wrote Mallinathapurana (1105), an account of the evolution of the soul of the Jain saint. According to some historians, King Veera Ballala I was his patron.[55] Later, he wrote his magnum opus, a Jain version of the Hindu epic Ramayana called Ramachandra Charitapurana (or Pampa Ramayana). Written in the traditional champu metre and in the Pauma charia tradition of Vimalasuri, it is the earliest extant version of the epic in the Kannada language.[32] The work contains 16 sections and deviates significantly from the original epic by Valmiki. Nagachandra represents King Ravana, the villain of the Hindu epic, as a tragic hero, who in a moment of weakness commits the sin of abducting Sita (wife of the Hindu god Rama) but is eventually purified by her devotion to Rama. In a further deviation, Rama's loyal brother Lakshmana (instead of Rama) kills Ravana in the final battle.[32] Eventually, Rama takes jaina-diksha (converts to Digambara monk), becomes an ascetic and attains nirvana (enlightenment). Considered a complementary work to the Pampa Bharatha of Adikavi Pampa (941, a Jain version of the epic Mahabharata), the work earned Nagachandra the honorific "Abhinava Pampa" ("new Pampa").[56] Only in the Kannada language do Jain versions exist of the Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, in addition to their brahminical version.[57]

Kanti (1108), known for her wit and humour, was one of the earliest female poets of the Kannada language and a contemporary of Nagachandra, with whom she indulged in debates and repartees.[58] Rajaditya, a native of either Puvinabage or Raibhag (the modern Belgaum district), was in the Hoysala court during the days of King Veera Ballala I and King Vishnuvardhana.[55][59] He wrote in easy verse on arithmetic and other mathematical topics and is credited with three of the earliest writings on mathematics in the Kannada language: Vyavaharaganita, Kshetraganita and Lilavati.[8] Udayaditya, a Chola prince, authored a piece on rhetoric called Udayadityalankara (1150). It was based on Dandin's Sanskrit Kavyadarsa.[8]

Age of Harihara

Harihara (or Harisvara, 1160), who came from a family of karnikas (accountants) in Hampi, was one of the earliest Veerashaiva writers who was not part of the Vachana poetic tradition. He is considered one of the most influential Kannada poets of the Hoysala era. A non-traditionalist, he has been called "poet of poets" and a "poet for the masses". Kannada poetry changed course because of his efforts, and he was an inspiration for generations of poets to follow.[60][61] Impressed by his early writings, Kereya Padmarasa, the court poet of King Narasimha I, introduced him to the king, who became Harihara's patron.[62] A master of many metres, he authored the Girijakalyana ("Marriage of the mountain born goddess – Parvati") in the Kalidasa tradition, employing the champu style to tell a 10-part story leading to the marriage of the god Shiva and Parvati.[63][64] According to an anecdote, Harihara was so against eulogising earthly mortals that he struck his protégé Raghavanka for writing about King Harishchandra in the landmark work Harishchandra Kavya (c. 1200).[65] Harihara is credited with developing the native ragale metre.[66] The earliest poetic biographer in the Kannada language, he wrote a biography of Basavanna called Basavarajadevara ragale, which gives interesting details about the protagonist while not always conforming to popular beliefs of the time.[67][68] Ascribed to him is a group of 100 poems called the Nambiyanana ragale (also called Shivaganada ragale or Saranacharitamanasa – "The holy lake of the lives of the devotees") after the saint Nambiyana.[31][63][69] In the sataka metre he wrote the Pampa sataka, and in the ashtaka metre, the Mudige ashtaka in about 1200.[33]

Famous among Vaishnava writers and the first brahmin writer (of the Smartha sect) of repute, Rudrabhatta wrote Jagannatha Vijaya (1180) in a style considered a transition between ancient and medieval Kannada.[70] Chandramouli, a minister in the court of King Veera Ballala II, was his patron. The writing, in champu metre, is about the life of the god Krishna. Leading to the god's fight with Banasura, it is based on an earlier writing, Vishnupurana.[71]

Nemichandra, court poet of King Veera Ballala II and the Silhara King Lakshmana of Kholapur, wrote Lilavati Prabandham (1170), the earliest available true fiction (and hence a novel) in Kannada, with an erotic bent.[70][72] Written in the champu metre, with the ancient town Banavasi as the background, it narrates the love story of a Kadamba prince and a princess who eventually marry after facing many obstacles.[8] The story is based on a c. 610 Sanskrit original called Vasavadatta by Subhandu.[72] His other work, Neminathapurana, unfinished on account of his death (and hence called Ardhanemi or "incomplete Nemi"), details the life of the 22nd Jain tirthankar Neminatha while treating the life of the god Krishna from a Jain angle.[73]

Palkuriki Somanatha, a native of modern Karnataka or Andhra Pradesh, is considered one of the foremost multi-lingual Shaiva (or Shiva-following) poets of the 12th and 13th centuries. Historians are divided about the time and place of his birth and death and his original faith. He was adept in the Sanskrit, Telugu and Kannada languages. He was a devotee of Basavanna (the founder of the Veerashaiva movement), and all his writings propagate that faith.[74] It is generally accepted that he was born a brahmin and later adopted the Shaiva faith, although according to the scholar Bandaru Tammayya he was born a Jangama (follower of the Shaiva faith).[74] His time of birth has been identified as either the 12th century[75] or late 13th century.[76] In Kannada, his most important writings are Silasampadane, Sahasragananama and Pancharatna. His well-known poems, written in the ragale metre, are Basava ragale, Basavadhya ragale and Sadguru ragale. He is known to have humbled many Vaishnava poets in debates.[74][77]

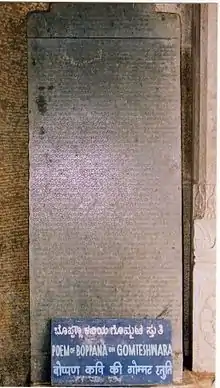

Other well-known personalities from the 12th century included several Jain writers. These include Aggala, who authored Chandraprabhapurana (1189),[72] an account of the life of the eighth Jain tirthankar Chandraprabha; Sujanottamsa, who wrote a panegyric on Gomateshwara of Shravanabelagola; and Vritta Vilasa, who authored Sastra sara and Dharmaparikshe (1160). The latter was Vilasa's version of the Sanskrit original of the same name written by Amitagati c. 1014. In this champu writing, the author narrates the story of two Kshatriya princess who went to Benares and exposed the vices of the gods after discussions with the brahmins there. The author questions the credibility of Hanuman (the Hindu monkey god) and the Vanaras (monkey-like humanoids in the Hindu epic Ramayana). Although controversial, the work sheds useful information on contemporary religious beliefs.[78][79] Kereya Padmarasa, a Veerashaiva poet patronised by King Narasimha I, wrote Dikshabodhe in the ragale metre in 1165. He would later become the protagonist of a biographical work called Padmarajapurana written by his descendant Padmanaka in c. 1400.[80] The brahmin poet Deva Kavi authored a romance piece called Kusumavali (1200), and brahmin poet Kavi Kama (12th century) authored a treatise called Sringara-ratnakara on the rasa (flavor) of poetical sentiment.[36] Sumanobana (1170) was a poet-grammarian and the Katakacharya ("military teacher") under King Narasimha I. He was also a priest in Devagiri, the Seuna Yadava capital.[26][38]

Jain–Veerashaiva conflict

Harihara's nephew and protégé, the dramatic poet Raghavanka of Hampi, whose style is compared to that of 10th-century poet Ranna, was the first to establish the shatpadi metre in Kannada literature in the epic Harishchandra Kavya (1200).[75][77] According to L. S. Seshagiri Rao, it is believed that in no other language has the story of King Harishchandra been interpreted in this way. The writing is an original in tradition and inspiration that fully develops the potential of the shatpadi metre.[25][81] The narration has many noteworthy elegiac verses such as the mourning of Chandramati over the death of her young son Lohitashva from snake bite.[82] The very writing that made Raghavanka famous was rejected by his guru, Harihara. His other well-known writings, adhering to strict Shaiva principles and written to appease his guru, are the Siddharama charitra (or Siddharama Purana), a larger than life stylistic eulogy of the compassionate 12th-century Veerashaiva saint, Siddharama of Sonnalige;[25] the Somanatha charitra, a propagandist work that describes the life of saint Somayya (or Adaiah) of Puligere (modern Lakshmeshwar), his humiliation by a Jain girl and his revenge; the Viresvara charita, a dramatic story of the blind wrath of a Shaiva warrior, Virabhadra; the Hariharamahatva, an account of the life of Harisvara of Hampi; and Sarabha charitra. The last two classics are considered lost.[77][81]

In 1209, the Jain scholar, minister, builder of temples and army commander Janna wrote, among other classics, Yashodhara Charite, a unique set of stories in 310 verses dealing with sadomasochism, transmigration of the soul, passion gone awry and cautionary morals for human conduct. The writing, although inspired by Vadiraja's Sanskrit classic of the same name, is noted for its original interpretation, imagery and style.[83] In one story, the poet tells of the infatuation of a man for his friend's wife. Having killed his friend, the man abducts the wife, who dies of grief. Overcome by repentance, he burns himself on the funeral pyre of the woman.[25][84] The stories of infatuation reach a peak when Janna writes about the attraction of Amrutamati, the queen, to the ugly mahout Ashtavakra, who pleases the queen with kicks and whip lashes. This story has piqued the interest of modern researchers.[85] In honour of this work, Janna received the title Kavichakravarthi ("Emperor among poets") from his patron, King Veera Ballala II.[75] His other classic, Anathanatha Purana (1230), is an account of the life of the 14th tirthankar Ananthanatha.[86][87]

Andayya, taking a non-conformist path that was never repeated in Kannada literature, wrote Madana Vijaya ("Triumph of cupid", 1217–1235) using only pure Kannada words (desya) and naturalised Sanskrit words (tadbhava) and totally avoiding assimilated Sanskrit words (tatsamas).[88] This is seen by some as a rebuttal meant to prove that writing Kannada literature without borrowed Sanskrit words was possible.[89] The poem narrates the story of the moon being imprisoned by the god Shiva in his abode in the Himalayas. In his anger, Kama (Cupid, the god of love, also called Manmata) assailed Shiva with his arrows only to be cursed by Shiva and separated from his beloved. Kama then contrived to rid himself of Shiva's curse. The work also goes by other names such as Sobagina Suggi ("Harvest of Beauty"), Kavane Gella ("Cupid's Conquest") and Kabbigara-kava ("Poets defender").[90] Kama has an important place in Jain writings even before Andayya. The possibility that this writing was yet another subtle weapon in the intensifying conflict between the dominant Jains[91] and the Veerashaivas, whose popularity was on the rise, is not lost on historians.[92]

Mallikarjuna, a Jain ascetic, compiled an anthology of poems called Suktisudharnava ("Gems from the poets") in 1245 in the court of King Vira Someshwara.[93] Some interesting observations have been made by scholars about this important undertaking. While the anthology itself provides insight into poetic tastes of that period (and hence qualifies as a "history of Kannada literature"), it also performs the function of a "guide for poets", an assertive method of bridging the gap between courtly literary intelligentsia and folk poetry.[94] Being a guide for "professional intellectuals", the work, true to its nature, often includes poems eulogising kings and royalty but completely ignoring poems of the 12th-century vachana canon (Veerashaiva folk literature).[37] However, the selection of poems includes contributions from Harihara, the non-conformist Veerashaiva writer. This suggests a compromise by which the author attempts to include the "rebels".[37]

Other notable writers of the early 13th century were Bhanduvarma, author of Harivamsabhyudaya and Jiva sambhodana (1200), the latter bearing on morals and renunciation, and written addressing the soul;[90] Balachandra Kavi Kandarpa, the author of the Belgaum fort inscription who claimed to be "master of four languages";[95] Maghanandycharya, the author of an extinct commentary on the Jain theological work Sastrasara Samuccaya-tiku (1209) for which there are references, and the available commentary called padarthasara giving a complete explanation of Sanskrit and Prakrit authoritative citations;[96][97] Hastimalla, who wrote Purvapurana;[96] Chandrama, author of Karkala Gomateshvara charite,[98] and Sisumayana, who introduced a new form of composition called sangatya in 1232. He wrote an allegorical poem called Tripuradahana ("Burning of the triple fortress") and Anjanacharita. The latter work was inspired by Ravisena's Sanskrit Padma charitra.[88][90] Somaraja, a Veerashaiva scholar, wrote a eulogy of Udbhata, the ruler of Gersoppa, and called it Sringarasara (or Udbhatakavya, 1222).[99] Other Jain writers were Parsva Pandita, author of Paravanathapurana, and Gunavarma II, the author of the story of the ninth Jain tirthankar Pushpadanta called Pushpadanta purana (both were patronised by the Ratta kings of Saundatti).[88][100] Polalva Dandanatha, a commander, minister, and the builder of the Harihareshwara temple in Harihar, wrote Haricharitra in 1224. He was patronised by King Veera Ballala II and his successor, King Vira Narasimha II.[100] Puligere Somanatha authored a book on morals called Somesvarasataka.[77]

Consolidation of grammar

Keshiraja was a notable writer and grammarian of the 13th century. He came from a family of famous poet-writers. Although five of Keshiraja's writings are not traceable, his most enduring work on Kannada grammar, Shabdamanidarpana ("Mirror of Word Jewels", 1260), is available and testifies to his scholarly acumen and literary taste.[26][90][101] True to his wish that his writing on grammar should "last as long as the sun, the moon, the oceans and the Meru mountain lasted", Shabdamanidarpana is popular even today and is considered a standard authority on old Kannada grammar. It is prescribed as a textbook for students of graduate and post-graduate studies in the Kannada language. Although Keshiraja followed the model of Sanskrit grammar (of the Katantra school) and that of earlier writings on Kannada grammar (by King Amoghavarsha I of the 9th century and grammarian Nagavarma II of 1145), his work has originality.[101] Keshiraja's lost writings are Cholapalaka Charitam, Sri Chitramale, Shubhadraharana, Prabodhachandra and Kiratam (or Kiratarjuniyam).[101]

A major development of this period that would have a profound impact on Kannada literature even into the modern age was the birth of the Haridasa ("servants of Hari or Vishnu") movement. This devotional movement, although reminiscent in some ways of the Veerashaiva movement of the 12th century (which produced Vachana poetry and taught devotion to the god Shiva), was in contrast intimately devoted to the Hindu god Vishnu as the supreme God.[102] The inspiration behind this movement was the philosophy of Madhvacharya of Udupi. Naraharitirtha (1281) is considered the first well-known haridasa and composer of Vaishnava devotional songs in Kannada. Before his induction into the Madhva order, he had served as a minister in the court of Kalinga (modern Orissa).[71] The Vaishnava poetry however disappeared for about two centuries after Naraharitirtha's death before resurfacing as a popular form of folk literature during the rule of the Vijayanagara Empire.[103] Only three of Naraharitirtha's compositions are available today.[104]

Other writers worthy of mention are Mahabala Kavi, the author of Neminathapurana (1254), an account of the 22nd Jain tirthankar Neminatha,[72] and Kumudendu, author of a Jain version of the epic Ramayana in shatpadi metre called Kumudendu Ramayana in 1275. The effort was influenced by Pampa Ramayana of Nagachandra.[105] Kumara Padmarasa, son of Kereya Padmarasa, wrote the Sananda Charitre in shatpadi metre.[106] Ratta Kavi, a Jain noble, wrote a quasi-scientific piece called Rattasutra (or Rattamala) in 1300. The writing bears on natural phenomena such rain, earthquakes, lightning, planets and omens.[26][90] A commentary on the Amara Khosa, considered useful to students of the language, called Amara Khosa Vyakhyana was written by the Jain writer Nachiraja (1300).[107] Towards the end of the Hoysala rule, Nagaraja wrote Punyasrava in 1331 in champu style, a work that narrates the stories of puranic heroes in 52 tales and is said to be a translation from Sanskrit.[26][90]

Sanskrit writings

The Vaishnava movement in the Kannada-speaking regions found momentum after the arrival of the philosopher Ramanujacharya (1017–1137). Fleeing possible persecution from the Chola King (who was a Shaiva), Ramanujacharya sought refuge initially in Tondanur and later moved to Melkote.[108] But this event had no impact on Vaishnava literature in Hoysala lands at that time. However, the teachings of Madhvacharya (1238–1317), propounder of the Dvaita philosophy, did have a direct impact on Vaishnava literature, in both the Sanskrit and Kannada languages. This body of writings is known as haridasa sahitya (haridasa literature).[103]

Born as Vasudeva in Pajaka village near Udupi in 1238, he learnt the Vedas and Upanishads under his guru Achyutapreksha. He was initiated into sanyasa (asceticism) after which he earned the name Madhvacharya (or Anandatirtha).[109] Later, he disagreed with the views of his guru and began to travel India. He successfully debated with many scholars and philosophers during this time and won over Naraharitirtha, a minister in Kalinga, who would later become Madhvacharya's first notable disciple. Unlike Adi Shankaracharya (788–820) who preached Advaita philosophy (monism) and Ramanujacharya who propounded Vishishtadvaita philosophy (qualified monism), Madhvacharya taught the Dvaita philosophy (dualism).[110]

Madhvacharya taught complete devotion to the Hindu god Vishnu, emphasising Jnanamarga or the "path of knowledge", and insisted that the path of devotion "can help a soul to attain elevation" (Athmonathi). He was however willing to accept devotion to other Hindu deities as well.[111] He wrote 37 works in Sanskrit including Dwadasha Sutra (in which his devotion to the god Vishnu found full expression), Gita Bhashya, Gita Tatparya Nirnaya, Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya, Bhagavata Tatparya Nirnaya, Mayavada Khandana and Vishnu Tattwa Nirnaya.[6][111] To propagate his teachings he established eight monasteries near Udupi, the Uttaradhi monastery, and the Raghavendra monastery in Mantralayam (in modern Andhra Pradesh) and Nanjanagud (near modern Mysore).[112]

The writings of Madhvacharya and Vidyatirtha (author of Rudraprshnabhashya) may have been absorbed by Sayanacharya, brother of Vidyaranya, the patron saint of the founders of the Vijayanagara empire in the 14th century.[113] Bharatasvamin (who was patronised by Hoysala King Ramanatha) wrote a commentary on Samaveda,[114] Shadgurusishya wrote commentary on Aitareya Brahmana and Aranyaka, and Katyayana wrote Sarvanukramani. A family of hereditary poets whose names have not been identified held the title "Vidyachakravarti" (poet laureate) in the Hoysala court. One of them wrote Gadyakarnamrita, a description of the war between Hoysala king Vira Narasimha II and the Pandyas, in the early 13th century.[115] His grandson with the same title, in the court of king Veera Ballala III, composed a poem called Rukminikalyana in 16 kandas (chapters) and wrote commentaries (on poetics) on the Alankarasarvasva and Kavyaprakasa.[115] Kalyani Devi, a sister of Madhvacharya, and Trivikrama, his disciple, wrote commentaries on the Dvaita philosophy. To Trivikrama is ascribed a poem narrating the story of Usha and Aniruddha called Ushaharana. Narayana Pandita composed Madhwavijaya, Manimanjari and a poem called Parijataharana. The Jain writer Ramachandra Maladhari authored Gurupanchasmriti.[55]

Literature after the Hoysalas

Literary developments during the Hoysala period had a marked influence on Kannada literature in the centuries to follow. These developments popularised folk metres which shifted the emphasis towards desi (native or folk) forms of literature.[116] With the waning of Jain literary output, competition between the Veerashaiva and Vaishnava writers came to the fore. The Veerashaiva writer Chamarasa (author of Prabhulingalile, 1425) and his Vaishnava competitor Kumaravyasa (Karnata Bharata Kathamanjari, 1450) popularised the shatpadi metric tradition initiated by Hoysala poet Raghavanka, in the court of Vijayanagara King Deva Raya II.[80][117] Lakshmisa, the 16th–17th century writer of epic poems, continued the tradition in the Jaimini Bharata, a work that has remained popular even in the modern period.[118] The tripadi metre, one of the oldest in the Kannada language (Kappe Arabhatta inscription of 700), which was used by Akka Mahadevi (Yoganna trividhi, 1160), was popularised in the 16th century by the mendicant poet Sarvajna.[119] Even Jain writers, who had dominated courtly literature throughout the classical period with their Sanskritic champu style, began to use native metres. Among them, Ratnakaravarni is famous for successfully integrating an element of worldly pleasure into asceticism and for treating the topic of eroticism with discretion in a religious epic written in the native sangatya metre (a metre initiated by Hoysala poet Sisumayana), his magnum opus, the Bharatadesa Vaibhava (c. 1557).[120][121]

Though the Vaishnava courtly writings in Kannada began with the Hoysala poet Rudrabhatta and the devotional song genre was initiated by Naraharitirtha, the Vaishnava movement began to exert a strong influence on Kannada literature only from the 15th century on. The Vaishnava writers consisted of two groups who seemed to have no interaction with each other: the Brahmin commentators who typically wrote under the patronage of royalty, and the Bhakti (devotion) writers (also known as haridasas) who played no role in courtly matters. The Bhakti writers took the message of God to the people in the form of melodious songs composed using folk genres such as the kirthane (a musical composition with refrain, based on tune and rhythm), the suladi (a composition based on rhythm) and the ugabhoga (a composition based on melody). Kumara Vyasa and Timmanna Kavi were well known among the Brahmin commentators, while Purandara Dasa and Kanaka Dasa were the most notable of the Bhakti writers.[122][123] The philosophy of Madhvacharya, which originated in the Kannada-speaking region in the 13th century, spread beyond its borders over the next two centuries. The itinerant haridasas, best described as mystic saint-poets, spread the philosophy of Madhvacharya in simple Kannada, winning mass appeal by preaching devotion to God and extolling the virtues of jnana (enlightenment), bhakti (devotion) and vairagya (detachment).[124][125]

Vachana poetry, developed in reaction to the rigid caste-based Hindu society, attained its peak in popularity among the under-privileged during the 12th century. Though these poems did not employ any regular metre or rhyme scheme, they are known to have originated from the earlier tripadi metrical form.[126] The Veerashaivas, who wrote this poetry, had risen to influential positions by the Vijayanagara period (14th century).[127] Court ministers and nobility belonging to the faith, such as Lakkanna Dandesa and Jakkanarya, not only wrote literature but also patronised talented writers and poets.[80][128][129] Veerashaiva anthologists of the 15th and 16th centuries began to collect Shaiva writings and vachana poems, originally written on palm leaf manuscripts.[127] Because of the cryptic nature of the poems, the anthologists added commentaries to them, thereby providing their hidden meaning and esoteric significance.[130] An interesting aspect of this anthological work was the translation of the Shaiva canon into Sanskrit, bringing it into the sphere of the Sanskritic (marga or mainstream as opposed to desi or folk) cultural order.[122]

See also

- Kannada literature

- Sanskrit literature

- Indian literature

Notes

- Kamath (2001), p. 132

- Thapar (2003), p. 368

- Kamath (2001), p. 129

- Kamath (2001), pp. 133–134

- Pollock (2006), pp. 288–289

- Kamath (2001), p. 155

- Shiva Prakash in Ayyappapanicker (1997), pp. 164, 203; Rice E. P. (1921), p. 59

- Sastri (1955), p. 358

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 20–21; E.P.Rice (1921), pp. 43–45; Sastri (1955) p. 364

- Quote:"A purely Karnataka dynasty" (Moraes 1931, p. 10)

- Rice, B. L. (1897), p. 335

- Natives of South Karnataka (Chopra 2003, p. 150 Part–1)

- Keay (2000), p. 251

- From the Marle inscription (Chopra 2003, p. 149, part–1)

- Kamath (2001), p. 124

- Keay (2000), p. 252

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 19

- Sastri (1955), p. 361

- Nagaraj in Pollock (2003), p. 366

- Rudrabhatta and Naraharitirtha (Sastri, 1955, p. 364)

- Kavi Kama and Deva (Narasimhacharya 1988, p. 20)

- Rajaditya's ganita (mathematics) writings (1190) and Ratta Kavi's Rattasutra on natural phenomena are examples (Sastri 1955, pp. 358–359)

- Shiva Prakash (1997), pp. 164, 203

- Rice E. P. (1921), p. 59

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1181

- E.P.Rice (1921), p. 45

- Sastri (1955), p. 357

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 61, 65

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 61

- Sastri (1955), pp. 359, 362

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 205

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1180

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 248

- Belur Keshavadasa in the book Karnataka Bhaktavijaya (Sahitya Akademi 1987, p. 881)

- Sahitya Akademi 1987, p. 881

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 20, 62

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 364

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), pp. 1475–1476

- Ayyar (2006), p. 600

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 68

- Kamath (2001) p. 143, pp. 114–115

- Masica (1991), pp. 45–46

- Velchuru Narayana Rao in Pollock (2003), pp. 383–384

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 27–28

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1182

- Shahitya Akademi (1987), p. 612

- Nagaraj (2003), pp. 377–379

- Rice Lewis (1985), p. xx

- Rice Lewis (1985), p. xxi

- Rice Lewis (1985), p. xxiii

- Rice Lewis (1985), xxiv

- Rice Lewis (1985), xxvi

- Rice Lewis (1985), pp. xxiv–xxv

- Keay 2000, p. 251

- Kamath (2001), p. 133

- Sastri (1955), pp. 357–358

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 66

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1603

- Rice E. P. (1921), p. 36

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 191

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), pp. 1411–1412, p. 1550

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1548

- Sastri (1955), pp. 361–362

- Narasimhacharya, (1988), p. 20

- Nagara (2003), p. 364

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), pp. 551–552

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 179

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), pp. 403–404

- Rice E. P. (1921), p. 60

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 203

- Sastri (1955) p. 364

- Rice E. P. (1921), p. 43

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 620; (1988), p. 1180

- Sahitya Akademi (1992), p. 4133

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 20

- Seshayya in Sahitya Akademi (1992), p. 4133

- Sastri (1955), p. 362

- Rice B. L. (1897), p. 499

- Rice E. P. (1921), pp. 37

- Sahitya Akademi (1992), p. 4003

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 207

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1149

- Sahitya Akademi (1992), p. 4629

- Rice E. P. (1921), pp. 43–44

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 204

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 620

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 377

- E.P.Rice (1921), pp. 43–44

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 170

- Sastri (1955), p. 359

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 65

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 366

- Rice E.P. (1921), p. 44–45

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 363

- Karnataka State Gazetteer: Belgaum (1973), p.721, Bangalore, Director of Print, Stationery and Publications at the Government Press

- Singh (2001), p. 975

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p.761

- Singh (2001), p. 979

- Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 21

- Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 20–21

- Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1476

- Shiva Prakash (1997), pp. 192–193

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 192

- Shiv Prakash (1997), p. 195

- Rice E. P. (1921), p. 45

- Sahitya Academi (1992), p. 4003

- Rice E.P. (1921), p.112

- Kamath (2001), p. 151

- Kamath (2001), p. 154

- Kamath (2001), pp. 150, 155

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 193

- Kamath (2001), pp. 155–156

- K. T. Pandurangi in Kamath 2001, pp. 132–133

- Sastri (1955), p. 310

- Sastri (1955), p. 316

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 167

- Sastri (1955), p. 364

- Sahitya Akademi, (1992), p. 4004

- Sahitya Akademi (1992), p. 4392

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 373

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), pp. 453–454

- Nagaraj (2003), p. 368

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 193–194

- Sharma (1961), p. 514–515

- Shiva Prakash (1997), pp. 192–196

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 169

- Shiva Prakash (1997), p. 188

- Rice E.P. (1921), p. 70

- Sastri (1955), p. 363

- Sahitya Akademi (1987), p. 761

References

- Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1993) [1993]. South Indian Shrines. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0151-3.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A concise history of Karnataka : from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.

- Keay, John (2000) [2000]. India: A History. New York: Grove Publications. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Lewis, Rice (1985). Nagavarmma's Karnataka Bhasha Bhushana. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0062-2.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991) [1991]. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29944-6.

- Moraes, George M. (1990) [1931]. The Kadamba Kula, A History of Ancient and Medieval Karnataka. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0595-0.

- Nagaraj, D.R. (2003) [2003]. "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture". In Sheldon I. Pollock (ed.). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. p. 1066. pp. 323–383. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- Rao, Velchuru Narayana (2003) [2003]. "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture". In Sheldon I. Pollock (ed.). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. p. 1066. p. 383. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1988]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2006). The Language of Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture and Power in Pre-modern India. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. p. 703. ISBN 0-520-24500-8.

- Rice, E. P. (1982) [1921]. Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0063-0.

- Rice, B. L. (2001) [1897]. Mysore Gazetteer Compiled for Government-vol 1. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0977-8.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K. A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Sharma, B.N.K (2000) [1961]. History of Dvaita school of Vedanta and its Literature (3rd ed.). Bombay: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1575-0.

- Shiva Prakash, H.S. (1997). "Kannada". In Ayyappapanicker (ed.). Medieval Indian Literature:An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-0365-0.

- Singh, Narendra (2001). "Classical Kannada Literature and Digambara Jain Iconography". Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-261-0691-3.

- Thapar, Romila (2003) [2003]. The Penguin History of Early India. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-302989-4.

- Various (1987). Amaresh Datta (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 1. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1803-8.

- Various (1988). Amaresh Datta (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- Various (1992). Mohan Lal (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 5. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

External links

- "History of Kannada Literature-I". History of Kannada Literature. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Rice E. P (1 December 1982). History of Kannada Literature Book by Rice E. P. History of Kannada Literature. ISBN 978-81-206-0063-8. Retrieved 8 March 2008.