Jaundice

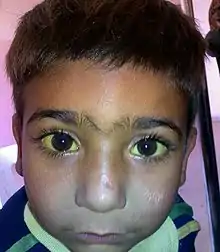

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels.[3][6] Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme metabolism, liver dysfunction, or biliary-tract obstruction.[7] The prevalence of jaundice in adults is rare, while jaundice in babies is common, with an estimated 80% affected during their first week of life.[8] The most commonly associated symptoms of jaundice are itchiness,[2] pale feces, and dark urine.[4]

| Jaundice | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Icterus[1] |

| |

| Jaundice of the skin caused by pancreatic cancer | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, hepatology, general surgery |

| Symptoms | Yellowish coloration of skin and sclera, itchiness[2][3] |

| Causes | High bilirubin levels[3] |

| Risk factors | Pancreatic cancer, Pancreatitis, Liver disease, Certain infections |

| Diagnostic method | Blood bilirubin, liver panel[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Carotenemia, taking rifampin[4] |

| Treatment | Based on the underlying cause[5] |

Normal levels of bilirubin in blood are below 1.0 mg/dl (17 μmol/L), while levels over 2–3 mg/dl (34–51 μmol/L) typically result in jaundice.[4][9] High blood bilirubin is divided into two types – unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin.[10]

Causes of jaundice vary from relatively benign to potentially fatal.[10] High unconjugated bilirubin may be due to excess red blood cell breakdown, large bruises, genetic conditions such as Gilbert's syndrome, not eating for a prolonged period of time, newborn jaundice, or thyroid problems.[4][10] High conjugated bilirubin may be due to liver diseases such as cirrhosis or hepatitis, infections, medications, or blockage of the bile duct,[4] due to factors including gallstones, cancer, or pancreatitis.[4] Other conditions can also cause yellowish skin, but are not jaundice, including carotenemia, which can develop from eating large amounts of foods containing carotene — or medications such as rifampin.[4]

Treatment of jaundice is typically determined by the underlying cause.[5] If a bile duct blockage is present, surgery is typically required; otherwise, management is medical.[5] Medical management may involve treating infectious causes and stopping medication that could be contributing to the jaundice.[5] Jaundice in newborns may be treated with phototherapy or exchanged transfusion depending on age and prematurity when the bilirubin is greater than 4–21 mg/dl (68–360 μmol/L).[9] The itchiness may be helped by draining the gallbladder, ursodeoxycholic acid, or opioid antagonists such as naltrexone.[2] The word "jaundice" is from the French jaunisse, meaning "yellow disease".[11][12]

Signs and symptoms

The most common signs of jaundice in adults are a yellowish discoloration of the white area of the eye (sclera) and skin[13] with scleral icterus presence indicating a serum bilirubin of at least 3 mg/dl.[14] Other common signs include dark urine (bilirubinuria) and pale (acholia) fatty stool (steatorrhea).[15] Because bilirubin is a skin irritant, jaundice is commonly associated with severe itchiness.[16][17]

Eye conjunctiva has a particularly high affinity for bilirubin deposition due to high elastin content. Slight increases in serum bilirubin can, therefore, be detected early on by observing the yellowing of sclerae. Traditionally referred to as scleral icterus, this term is actually a misnomer, because bilirubin deposition technically occurs in the conjunctival membranes overlying the avascular sclera. Thus, the proper term for the yellowing of "white of the eyes" is conjunctival icterus.[18]

A much less common sign of jaundice specifically during childhood is yellowish or greenish teeth. In developing children, hyperbilirubinemia may cause a yellow or green discoloration of teeth due to bilirubin deposition during the process of tooth calcification.[19] While this may occur in children with hyperbilirubinemia, tooth discoloration due to hyperbilirubinemia is not observed in individuals with adult-onset liver disease. Disorders associated with a rise in serum levels of conjugated bilirubin during early development can also cause dental hypoplasia.[20]

Causes

Jaundice is a sign indicating the presence of an underlying diseases involving abnormal bilirubin metabolism, liver dysfunction, or biliary-tract obstruction. In general, jaundice is present when blood levels of bilirubin exceed 3 mg/dl.[14] Jaundice is classified into three categories, depending on which part of the physiological mechanism the pathology affects. The three categories are:

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Prehepatic/hemolytic | The pathology occurs prior to the liver metabolism, due to either intrinsic causes to red blood cell rupture or extrinsic causes to red blood cell rupture. |

| Hepatic/hepatocellular | The pathology is due to damage of parenchymal liver cells. |

| Posthepatic/cholestatic | The pathology occurs after bilirubin conjugation in the liver, due to obstruction of the biliary tract and/or decreased bilirubin excretion.[21] |

Prehepatic causes

Prehepatic jaundice is most commonly caused by a pathological increased rate of red blood cell (erythrocyte) hemolysis. The increased breakdown of erythrocytes → increased unconjugated serum bilirubin → increased deposition of unconjugated bilirubin into mucosal tissue.[22] These diseases may cause jaundice due to increased erythrocyte hemolysis:[23]

- Sickle-cell anemia[24]

- Spherocytosis[25]

- Thalassemia[26]

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome

- Severe malaria (in endemic countries)

Hepatic causes

Hepatic jaundice is caused by abnormal liver metabolism of bilirubin.[27] The major causes of hepatic jaundice are significant damage to hepatocytes due to infectious, drug/medication-induced, autoimmune etiology, or less commonly, due to inheritable genetic diseases.[28] The following is a partial list of hepatic causes to jaundice:

- Acute hepatitis

- Chronic hepatitis

- Hepatotoxicity

- Cirrhosis

- Drug-induced hepatitis

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Gilbert's syndrome (found in about 5% of the population, results in induced mild jaundice)

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome, type I

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome, type II

- Leptospirosis

Posthepatic causes (Obstructive jaundice)

Posthepatic jaundice (obstructive jaundice), is caused by a blockage of bile ducts that transport bile containing conjugated bilirubin out of the liver for excretion.[29] This is a list of conditions that can cause posthepatic jaundice:

- Choledocholithiasis (common bile duct gallstones). It is the most common cause of obstructive jaundice.

- Pancreatic cancer of the pancreatic head

- Biliary tract strictures

- Biliary atresia

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Cholestasis of pregnancy

- Acute Pancreatitis

- Chronic Pancreatitis

- Pancreatic pseudocysts

- Mirizzi's syndrome

- Parasites ("liver flukes" of the Opisthorchiidae and Fasciolidae)[30]

Pathophysiology

Jaundice is typically caused by an underlying pathological process that occurs at some point along the normal physiological pathway of heme metabolism. A deeper understanding of the anatomical flow of normal heme metabolism is essential to appreciate the importance of prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic categories. Thus, an anatomical approach to heme metabolism precedes a discussion of the pathophysiology of jaundice.

Prehepatic metabolism

When red blood cells complete their lifespan of about 120 days, or if they are damaged, they rupture as they pass through the reticuloendothelial system, and cell contents including hemoglobin are released into circulation. Macrophages phagocytose free hemoglobin and split it into heme and globin. Two reactions then take place with the heme molecule. The first oxidation reaction is catalyzed by the microsomal enzyme heme oxygenase and results in biliverdin (green color pigment), iron, and carbon monoxide. The next step is the reduction of biliverdin to a yellow color tetrapyrrole pigment called bilirubin by cytosolic enzyme biliverdin reductase. This bilirubin is "unconjugated", "free", or "indirect" bilirubin. Around 4 mg of bilirubin per kg of blood are produced each day.[31] The majority of this bilirubin comes from the breakdown of heme from expired red blood cells in the process just described. Roughly 20% comes from other heme sources, however, including ineffective erythropoiesis, and the breakdown of other heme-containing proteins, such as muscle myoglobin and cytochromes.[31] The unconjugated bilirubin then travels to the liver through the bloodstream. Because this bilirubin is not soluble, it is transported through the blood bound to serum albumin.

Hepatic metabolism

Once unconjugated bilirubin arrives in the liver, liver enzyme UDP-glucuronyl transferase conjugates bilirubin + glucuronic acid → bilirubin diglucuronide (conjugated bilirubin). Bilirubin that has been conjugated by the liver is water-soluble and excreted into the gallbladder.

Posthepatic metabolism

Bilirubin enters the intestinal tract via bile. In the intestinal tract, bilirubin is converted into urobilinogen by symbiotic intestinal bacteria. Most urobilinogen is converted into stercobilinogen and further oxidized into stercobilin. Stercobilin is excreted via feces, giving stool its characteristic brown coloration.[32] A small portion of urobilinogen is reabsorbed back into the gastrointestinal cells. Most reabsorbed urobilinogen undergoes hepatobiliary recirculation. A smaller portion of reabsorbed urobilinogen is filtered into the kidneys. In the urine, urobilinogen is converted to urobilin, which gives urine its characteristic yellow color.[32]

Abnormalities in heme metabolism and excretion

One way to understand jaundice pathophysiology is to organize it into disorders that cause increased bilirubin production (abnormal heme metabolism) or decreased bilirubin excretion (abnormal heme excretion).

Prehepatic pathophysiology

Prehepatic jaundice results from a pathological increase in bilirubin production: an increased rate of erythrocyte hemolysis causes increased bilirubin production, leading to increased deposition of bilirubin in mucosal tissues and the appearance of a yellow hue.

Hepatic pathophysiology

Hepatic jaundice (hepatocellular jaundice) is due to significant disruption of liver function, leading to hepatic cell death and necrosis and impaired bilirubin transport across hepatocytes. Bilirubin transport across hepatocytes may be impaired at any point between hepatocellular uptake of unconjugated bilirubin and hepatocellular transport of conjugated bilirubin into the gallbladder. In addition, subsequent cellular edema due to inflammation causes mechanical obstruction of the intrahepatic biliary tract. Most commonly, interferences in all three major steps of bilirubin metabolism — uptake, conjugation, and excretion — usually occur in hepatocellular jaundice. Thus, an abnormal rise in both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin will be present. Because excretion (the rate-limiting step) is usually impaired to the greatest extent, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia predominates.[33]

The unconjugated bilirubin still enters the liver cells and becomes conjugated in the usual way. This conjugated bilirubin is then returned to the blood, probably by rupture of the congested bile canaliculi and direct emptying of the bile into the lymph exiting the liver. Thus, most of the bilirubin in the plasma becomes the conjugated type rather than the unconjugated type, and this conjugated bilirubin, which did not go to the intestine to become urobilinogen, gives the urine a dark color.[34]

Posthepatic pathophysiology

Posthepatic jaundice, also called obstructive jaundice, is due to the blockage of bile excretion from the biliary tract, which leads to increased conjugated bilirubin and bile salts there. In complete obstruction of the bile duct, conjugated bilirubin cannot access the intestinal tract, disrupting further bilirubin conversion to urobilinogen and, therefore, no stercobilin or urobilin is produced. In obstructive jaundice, excess conjugated bilirubin is filtered into the urine without urobilinogen. Conjugated bilirubin in urine (bilirubinuria) gives urine an abnormally dark brown color. Thus, the presence of pale stool (stercobilin absent from feces) and dark urine (conjugated bilirubin present in urine) suggests an obstructive cause of jaundice. Because these associated signs are also positive in many hepatic jaundice conditions, they cannot be a reliable clinical feature to distinguish obstructive versus hepatocellular jaundice causes.[35]

Diagnosis

Most people presenting with jaundice have various predictable patterns of liver panel abnormalities, though significant variation does exist. The typical liver panel includes blood levels of enzymes found primarily from the liver, such as the aminotransferases (ALT, AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP); bilirubin (which causes the jaundice); and protein levels, specifically, total protein and albumin. Other primary lab tests for liver function include gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and prothrombin time (PT).[36] No single test can differentiate between various classifications of jaundice. A combination of liver function tests and other physical examination findings is essential to arrive at a diagnosis.[37]

Laboratory tests

| Prehepatic jaundice | Hepatic jaundice | Posthepatic jaundice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total serum bilirubin | Normal / increased | Increased | Increased |

| Conjugated bilirubin | Normal | Increased | Increased |

| Unconjugated bilirubin | Normal / increased | Increased | Normal |

| Urobilinogen | Normal / increased | Decreased | Decreased / negative |

| Urine color | Normal[38] | Dark (urobilinogen, conjugated bilirubin) | Dark (conjugated bilirubin) |

| Stool color | Brown | Slightly pale | Pale, white |

| Alkaline phosphatase levels | Normal | Increased | Highly increased |

| Alanine transferase and aspartate transferase levels | Highly increased | Increased | |

| Conjugated bilirubin in urine | Not present | Present | Present |

Some bone and heart disorders can lead to an increase in ALP and the aminotransferases, so the first step in differentiating these from liver problems is to compare the levels of GGT, which are only elevated in liver-specific conditions. The second step is distinguishing from biliary (cholestatic) or liver causes of jaundice and altered laboratory results. ALP and GGT levels typically rise with one pattern while aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) rise in a separate pattern. If the ALP (10–45 IU/L) and GGT (18–85 IU/L) levels rise proportionately as high as the AST (12–38 IU/L) and ALT (10–45 IU/L) levels, this indicates a cholestatic problem. If the AST and ALT rise is significantly higher than the ALP and GGT rise, though, this indicates a liver problem. Finally, distinguishing between liver causes of jaundice, comparing levels of AST and ALT can prove useful. AST levels typically are higher than ALT. This remains the case in most liver disorders except for hepatitis (viral or hepatotoxic). Alcoholic liver damage may have fairly normal ALT levels, with AST 10 times higher than ALT. If ALT is higher than AST, however, this is indicative of hepatitis. Levels of ALT and AST are not well correlated to the extent of liver damage, although rapid drops in these levels from very high levels can indicate severe necrosis. Low levels of albumin tend to indicate a chronic condition, while the level is normal in hepatitis and cholestasis.

Laboratory results for liver panels are frequently compared by the magnitude of their differences, not the pure number, as well as by their ratios. The AST:ALT ratio can be a good indicator of whether the disorder is alcoholic liver damage (above 10), some other form of liver damage (above 1), or hepatitis (less than 1). Bilirubin levels greater than 10 times normal could indicate neoplastic or intrahepatic cholestasis. Levels lower than this tend to indicate hepatocellular causes. AST levels greater than 15 times normal tend to indicate acute hepatocellular damage. Less than this tend to indicate obstructive causes. ALP levels greater than 5 times normal tend to indicate obstruction, while levels greater than 10 times normal can indicate drug (toxin) induced cholestatic hepatitis or cytomegalovirus infection. Both of these conditions can also have ALT and AST greater than 20 times normal. GGT levels greater than 10 times normal typically indicate cholestasis. Levels 5–10 times tend to indicate viral hepatitis. Levels less than 5 times normal tend to indicate drug toxicity. Acute hepatitis typically has ALT and AST levels rising 20–30 times normal (above 1000) and may remain significantly elevated for several weeks. Acetaminophen toxicity can result in ALT and AST levels greater than 50 times than normal.

Laboratory findings depend on the cause of jaundice:

- Urine: conjugated bilirubin present, urobilinogen > 2 units but variable (except in children)

- Plasma proteins show characteristic changes.

- Plasma albumin level is low, but plasma globulins are raised due to an increased formation of antibodies.

Unconjugated bilirubin is hydrophobic, so cannot be excreted in urine. Thus, the finding of increased urobilinogen in the urine without the presence of bilirubin in the urine (due to its unconjugated state) suggests hemolytic jaundice as the underlying disease process.[39] Urobilinogen will be greater than 2 units, as hemolytic anemia causes increased heme metabolism; one exception being the case of infants, where the gut flora has not developed). Conversely, conjugated bilirubin is hydrophilic and thus can be detected as present in the urine — bilirubinuria — in contrast to unconjugated bilirubin, which is absent in the urine.[40]

Imaging

Medical imaging such as ultrasound, CT scan, and HIDA scan are useful for detecting bile-duct blockage.[40]

Differential diagnosis

Yellow discoloration of the skin, especially on the palms and the soles, but not of the sclera or inside the mouth, is often due to carotenemia—a harmless condition.[41]

Treatment

Treatment of jaundice varies depending on the underlying cause.[5] If a bile duct blockage is present, surgery is typically required; otherwise, management is medical.[5][42][43][44]

Complications

Hyperbilirubinemia, more precisely hyperbilirubinemia due to the unconjugated fraction, may cause bilirubin to accumulate in the grey matter of the central nervous system, potentially causing irreversible neurological damage, leading to a condition known as kernicterus. Depending on the level of exposure, the effects range from unnoticeable to severe brain damage and even death. Newborns are especially vulnerable to hyperbilirubinemia-induced neurological damage, so must be carefully monitored for alterations in their serum bilirubin levels.

Individuals with parenchymal liver disease who have impaired hemostasis may develop bleeding problems.[45]

Epidemiology

Jaundice in adults is rare.[46][47][48] Under the five year DISCOVERY programme in the UK, annual incidence of jaundice was 0.74 per 1000 individuals over age 45, although this rate may be slightly inflated due to the main goal of the programme collecting and analyzing cancer data in the population.[49] Jaundice is commonly associated with severity of disease with an incidence of up to 40% of patients requiring intensive care in ICU experiencing jaundice.[48] The causes of jaundice in the intensive care setting is both due to jaundice as the primary reason for ICU stay or as a morbidity to an underlying disease (i.e. sepsis).[48]

In the developed world, the most common causes of jaundice are blockage of the bile duct or medication-induced. In the developing world, the most common cause of jaundice is infectious such as viral hepatitis, leptospirosis, schistosomiasis, or malaria.[4]

Risk factors

Risk factors associated with high serum bilirubin levels include male gender, white ethnicities, and active smoking.[50] Mean serum total bilirubin levels in adults were found to be higher in men (0.72 ± 0.004 mg/dl) than women (0.52 ± 0.003 mg/dl).[50] Higher bilirubin levels in adults are found also in non-Hispanic white population (0.63 ± 0.004 mg/dl) and Mexican American population (0.61 ± 0.005 mg/dl) while lower in non-Hispanic black population (0.55 ± 0.005 mg/dl).[50] Bilirubin levels are higher in active smokers.[50]

Special populations

Symptoms

Jaundice in infants presents with yellowed skin and icteral sclerae. Neonatal jaundice spreads in a cephalocaudal pattern, affecting the face and neck before spreading down to the trunk and lower extremities in more severe cases.[51] Other symptoms may include drowsiness, poor feeding, and in severe cases, unconjugated bilirubin can cross the blood-brain barrier and cause permanent neurological damage (kernicterus).

Causes

The most common cause of jaundice in infants is normal physiologic jaundice. Pathologic causes of neonatal jaundice include:

- Formula jaundice[52]

- Hereditary spherocytosis

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency

- ABO/Rh blood type autoantibodies

- Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Alagille syndrome (genetic defect resulting in hypoplastic intrahepatic bile ducts)

- Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- Pyknocytosis (due to vitamin deficiency)

- Cretinism (congenital hypothyroidism)

- Sepsis or other infectious causes

Pathophysiology

Transient neonatal jaundice is one of the most common conditions occurring in newborns (children under 28 days of age) with more than 80 per cent experienceing jaundice during their first week of life.[53] Jaundice in infants, as in adults, is characterized by increased bilirubin levels (infants: total serum bilirubin greater than 5 mg/dL).

Normal physiological neonatal jaundice is due to immaturity of liver enzymes involved in bilirubin metabolism, immature gut microbiota, and increased breakdown of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).[54] Breast milk jaundice is caused by an increased concentration of β-glucuronidase in breast milk, which increases bilirubin deconjugation and reabsorption of bilirubin, leading to persistence of physiologic jaundice with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Onset of breast milk jaundice is within 2 weeks after birth and lasts for 4–13 weeks.

While most cases of newborn jaundice are not harmful, when bilirubin levels are very high, brain damage — kernicterus — may occur[55][8] leading to significant disability.[56] Kernicterus is associated with increased unconjugated bilirubin (bilirubin which is not carried by albumin). Newborns are especially vulnerable to this damage, due to increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier occurring with increased unconjugated bilirubin, simultaneous to the breakdown of fetal hemoglobin and the immaturity of gut flora. This condition has been rising in recent years. as babies spend less time in sunlight.

Treatment

Jaundice in newborns is usually transient and dissipates without medical intervention. In cases when serum bilirubin levels are greater than 4–21 mg/dl (68–360 μmol/L), infant may be treated with phototherapy or exchanged transfusion depending on the infant's age and prematurity status.[9] A bili light is often the tool used for early treatment, which often consists of exposing the baby to intensive phototherapy.[57] A 2014 systematic review found no evidence indicating whether outcomes were different for hospital-based versus home-based treatment.[58] A 2021 Cochrane systematic review found that sunlight can be used to supplement phototherapy, as long as care is taken to prevent overheating and skin damage.[59] There was not sufficient evidence to conclude that sunlight by itself is an effective treatment.[59] Bilirubin count is also lowered through excretion — bowel movements and urination —so frequent and effective feedings are vital measures to decrease jaundice in infants.[60]

Etymology

Jaundice comes from the French jaune, meaning yellow, jaunisse meaning "yellow disease". The medical term for it is icterus from the Greek word ikteros.[61] The origin of the word icterus is quite bizarre, coming from an ancient belief that jaundice could be cured by looking at the yellow bird icteria.[62] The term icterus is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to jaundice specifically of sclera.[61][63]

References

- Torre DM, Lamb GC, Ruiswyk JV, Schapira RM (2009). Kochar's Clinical Medicine for Students. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 101. ISBN 9780781766999.

- Bassari R, Koea JB (February 2015). "Jaundice associated pruritis: a review of pathophysiology and treatment". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 21 (5): 1404–13. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1404. PMC 4316083. PMID 25663760.

- Jaundice. MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Jones R (2004). Oxford Textbook of Primary Medical Care. Oxford University Press. p. 758. ISBN 9780198567820. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Ferri FF (2014). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2015: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 672. ISBN 9780323084307. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Buttaro TM, Trybulski J, Polgar-Bailey P, Sandberg-Cook J (2012). Primary Care: A Collaborative Practice (4 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 690. ISBN 978-0323075855. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Al-Tubaikh, Jarrah Ali (2017). Internal Medicine. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-39747-4. ISBN 978-3-319-39746-7.

- Kaplan M, Hammerman C (2017). "Hereditary Contribution to Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia". Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. Elsevier: 933–942.e3. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-35214-7.00097-4. ISBN 978-0-323-35214-7.

- Maisels MJ (March 2015). "Managing the jaundiced newborn: a persistent challenge". CMAJ. 187 (5): 335–43. doi:10.1503/cmaj.122117. PMC 4361106. PMID 25384650.

- Winger J, Michelfelder A (September 2011). "Diagnostic approach to the patient with jaundice". Primary Care. 38 (3): 469–82, viii. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2011.05.004. PMID 21872092.

- Dr. Chase's Family Physician, Farrier, Bee-keeper, and Second Receipt Book,: Being an Entirely New and Complete Treatise ... Chase Publishing Company. 1873. p. 542. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Sullivan KM, Gourley GR (2011). Jaundice. Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Elsevier. pp. 176–186.e3. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4377-0774-8.10017-x. ISBN 978-1-4377-0774-8.

- Gondal B, Aronsohn A (December 2016). "A Systematic Approach to Patients with Jaundice". Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 33 (4): 253–258. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1592331. PMC 5088098. PMID 27904243.

- Reuben A (2012). "Jaundice". Textbook of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 84–92. doi:10.1002/9781118321386.ch15. ISBN 978-1-118-32138-6.

- Goroll AH (2009). Primary care medicine : office evaluation and management of the adult patient (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 496. ISBN 9780781775137. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- James, William D. (2006). Andrews' diseases of the skin : clinical dermatology. Berger, Timothy G., Elston, Dirk M., Odom, Richard B., 1937– (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0. OCLC 62736861.

- Bassari, Ramez (2015). "Jaundice associated pruritis: A review of pathophysiology and treatment". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 21 (5): 1404–1413. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i5.1404. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 4316083. PMID 25663760.

- McGee, Steven R. (2018). "Jaundice". Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 59–68. ISBN 978-0-323392761.

- Neville BW (2012). Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (3rd ed.). Singapore: Elsevier. p. 798. ISBN 9789814371070.

- Amin SB, Karp JM, Benzley LP (May 2010). "Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and early childhood caries in a diverse group of neonates". American Journal of Perinatology. 27 (5): 393–7. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1243314. PMC 3264945. PMID 20013583.

- Chatterjea MN, Shinde R (2012). Textbook of medical biochemistry (8th ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publications (P) Ltd. p. 672. ISBN 978-93-5025-484-4.

- Joseph, Abel; Samant, Hrishikesh (2022), "Jaundice", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31334972, retrieved 23 April 2022

- "What causes jaundice in hemolytic anemia?". www.medscape.com. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- "What Is Sickle Cell Disease?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 12 June 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Robert S. Hillman; Kenneth A. Ault; Henry M. Rinder (2005). Hematology in clinical practice: a guide to diagnosis and management. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-07-144035-6. Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- "Thalassemia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Kalakonda, Aditya; Jenkins, Bianca A.; John, Savio (2022), "Physiology, Bilirubin", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261920, retrieved 23 April 2022

- Tripathi, Nishant; Jialal, Ishwarlal (2022), "Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965843, retrieved 23 April 2022

- "Bilirubin Metabolism – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- "CDC – Liver Flukes". www.cdc.gov. 18 April 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Pashankar D, Schreiber RA (July 2001). "Jaundice in older children and adolescents". Pediatrics in Review. 22 (7): 219–26. doi:10.1542/pir.22-7-219. PMID 11435623. S2CID 11100275.

- Berthelot, P.; Duvaldestin, Ph.; Fevery, J. (18 January 2018), "Physiology and Disorders of Human Bilirubin Metabolism", Bilirubin, CRC Press, pp. 173–214, doi:10.1201/9781351070119-6, ISBN 978-1-351-07011-9

- Mathew KG (2008). Medicine: Prep Manual for Undergraduates (3rd ed.). Elsevier India. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-8131211540.

- Hall JE, Guyton AC (2011). Textbook of Medical Physiology. Saunders/Elsevier. p. 841. ISBN 978-1416045748.

- Beckingham IJ, Ryder SD (January 2001). "ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system. Investigation of liver and biliary disease". BMJ. 322 (7277): 33–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7277.33. PMC 1119305. PMID 11141153.

- "Liver Function Tests". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Roche SP, Kobos R (2004). "Jaundice in the Adult Patient". American Family Physician. 69 (2): 299–304. PMID 14765767. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Llewelyn H, Ang HA, Lewis K, Al-Abdullah A (2014). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis. Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780199679867. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Cadogen M (21 April 2019). "Bilirubin and Jaundice". Life in the Fast Lane. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Roche SP, Kobos R (January 2004). "Jaundice in the adult patient". American Family Physician. 69 (2): 299–304. PMID 14765767.

- Carotenemia at eMedicine

- Wang, Long; Yu, Wei-Feng (March 2014). "Obstructive jaundice and perioperative management". Acta Anaesthesiologica Taiwanica. 52 (1): 22–29. doi:10.1016/j.aat.2014.03.002. ISSN 1875-4597. PMID 24999215.

- Dixon, Elijah; Vollmer, Charles M.; May, Gary R., eds. (2015). Management of Benign Biliary Stenosis and Injury. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22273-8. ISBN 978-3-319-22272-1.

- Lorenz, Jonathan (31 October 2016). "Management of Malignant Biliary Obstruction". Seminars in Interventional Radiology. 33 (4): 259–267. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1592330. ISSN 0739-9529. PMC 5088103. PMID 27904244.

- Neville BW (2012). Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology (3rd ed.). Singapore: Elsevier. p. 798. ISBN 9789814371070.

- Ahmad J, Friedman SL, Dancygier H (2014). Mount Sinai Expert Guides: Hepatology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118742525. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Björnsson, Einar; Gustafsson, Jonas; Borkman, Jakob; Kilander, Anders (2008). "Fate of patients with obstructive jaundice". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 3 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1002/jhm.272. ISSN 1553-5592. PMID 18438808.

- Bansal, Vishal; Schuchert, Vaishali Dixit (December 2006). "Jaundice in the Intensive Care Unit". Surgical Clinics of North America. 86 (6): 1495–1502. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2006.09.007. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 17116459.

- Taylor, Anna; Stapley, Sally; Hamilton, William (1 August 2012). "Jaundice in primary care: a cohort study of adults aged >45 years using electronic medical records". Family Practice. 29 (4): 416–420. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr118. ISSN 0263-2136. PMID 22247287.

- Zucker, Stephen D.; Horn, Paul S.; Sherman, Kenneth E. (October 2004). "Serum bilirubin levels in the U.S. Population: Gender effect and inverse correlation with colorectal cancer". Hepatology. 40 (4): 827–835. doi:10.1002/hep.1840400412. PMID 15382174. S2CID 25854541.

- Telega, Grzegorz W. (2018). "Jaundice". Nelson Pediatric Symptom-Based Diagnosis. Elsevier. pp. 255–274.e1. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-39956-2.00015-7. ISBN 978-0-323-39956-2.

- Bertini G, Dani C, Tronchin M, Rubaltelli FF (March 2001). "Is breastfeeding really favoring early neonatal jaundice?". Pediatrics. 107 (3): E41. doi:10.1542/peds.107.3.e41. PMID 11230622.

- Maisels, M. Jeffrey (17 March 2015). "Managing the jaundiced newborn: a persistent challenge". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 187 (5): 335–343. doi:10.1503/cmaj.122117. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 4361106. PMID 25384650.

- Collier J, Longore M, Turmezei T, Mafi AR (2010). "Neonatal jaundice". Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922888-1.

- "Facts about Jaundice and Kernicterus". CDC. 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Click R, Dahl-Smith J, Fowler L, DuBose J, Deneau-Saxton M, Herbert J (2013). "An osteopathic approach to reduction of readmissions for neonatal jaundice". Osteopathic Family Physician. 5 (1): 17–23. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2012.09.005.

- "Bili Lights for Jaundice: Effectiveness for Neonatal and Adults | Heliotherapy Research Institute". Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- Malwade, Ujjwala S; Jardine, Luke A (2014). "Home- versus hospital-based phototherapy for the treatment of non-haemolytic jaundice in infants at more than 37 weeks' gestation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD010212. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010212.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 24913724.

- Horn, Delia; Ehret, Danielle; Gautham, Kanekal S; Soll, Roger (6 July 2021). Cochrane Neonatal Group (ed.). "Sunlight for the prevention and treatment of hyperbilirubinemia in term and late preterm neonates". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013277.pub2. PMC 8259558. PMID 34228352.

- O'Keefe L (May 2001). "Increased vigilance needed to prevent kernicterus in newborns". American Academy of Pediatrics. 18 (5): 231. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- "Definition of Icterus". MedicineNet.com. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Questions and Answers". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 186 (6): 615. 9 November 1963. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03710060101048. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Icterus | Define Icterus at Dictionary.com Archived 2010-12-31 at the Wayback Machine. Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved on 2013-12-23.