Acute pancreatitis

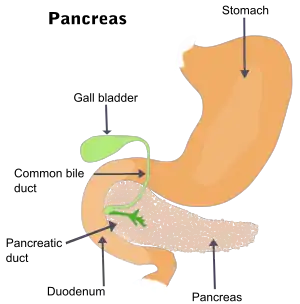

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. Causes in order of frequency include: 1) a gallstone impacted in the common bile duct beyond the point where the pancreatic duct joins it; 2) heavy alcohol use; 3) systemic disease; 4) trauma; 5) and, in minors, mumps. Acute pancreatitis may be a single event; it may be recurrent; or it may progress to chronic pancreatitis.

| Acute pancreatitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute pancreatic necrosis[1] |

| |

| 3D Medical Animation still shot of Acute Pancreatitis | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, general surgery |

Mild cases are usually successfully treated with conservative measures: hospitalization, pain control, nothing by mouth, intravenous nutritional support, and intravenous fluid rehydration. Severe cases often require admission to an intensive care unit to monitor and manage complications of the disease. Complications are associated with a high mortality, even with optimal management.

Signs and symptoms

Common

- severe epigastric pain (upper abdominal pain) radiating to the back in 50% of cases

- nausea[2]

- vomiting

- loss of appetite

- fever

- chills (shivering)

- hemodynamic instability, including shock

- tachycardia (rapid heartbeat)

- respiratory distress

- peritonitis

- hiccup

Although these are common symptoms, frequently they are not all present; and epigastric pain may be the only symptom.[3]

Uncommon

The following are associated with severe disease:

- Grey-Turner's sign (hemorrhagic discoloration of the flanks)

- Cullen's sign (hemorrhagic discoloration of the umbilicus)

- Pleural effusions (fluid in the bases of the pleural cavity)

- Grünwald sign (appearance of ecchymosis, large bruise, around the umbilicus due to local toxic lesion of the vessels)

- Körte's sign (pain or resistance in the zone where the head of pancreas is located (in epigastrium, 6–7 cm above the umbilicus))

- Kamenchik's sign (pain with pressure under the xiphoid process)

- Mayo-Robson's sign (pain while pressing at the top of the angle lateral to the erector spinae muscles and below the left 12th rib (left costovertebral angle (CVA))[4]

- Mayo-Robson's point – a point on border of inner 2/3 with the external 1/3 of the line that represents the bisection of the left upper abdominal quadrant, where tenderness on pressure exists in disease of the pancreas. At this point the tail of pancreas is projected on the abdominal wall.

Complications

Locoregional complications include pancreatic pseudocyst (most common, occurring in up to 25% of all cases, typically after 4–6 weeks) and phlegmon/abscess formation, splenic artery pseudoaneurysms, hemorrhage from erosions into splenic artery and vein, thrombosis of the splenic vein, superior mesenteric vein and portal veins (in descending order of frequency), duodenal obstruction, common bile duct obstruction, progression to chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic ascites, pleural effusion, sterile/infected pancreatic necrosis.[5]

Systemic complications include ARDS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, DIC, hypocalcemia (from fat saponification), hyperglycemia and insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (from pancreatic insulin-producing beta cell damage), malabsorption due to exocrine failure

- Metabolic

- Hypocalcemia, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia

- Respiratory

- Hypoxemia, atelectasis, Effusion, pneumonitis, Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Renal

- Renal artery or vein thrombosis

- Kidney failure

- Circulatory

- Arrhythmias

- Hypovolemia and shock

- myocardial infarction

- Pericardial effusion

- vascular thrombosis

- Gastrointestinal

- Gastrointestinal hemorrhage from stress ulceration;

- gastric varices (secondary to splenic vein thrombosis)

- Gastrointestinal obstruction

- Hepatobiliary

- Jaundice

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Neurologic

- Psychosis or encephalopathy (confusion, delusion and coma)

- Cerebral Embolism

- Blindness (angiopathic retinopathy with hemorrhage)

- Hematologic

- Dermatologic

- Painful subcutaneous fat necrosis

- Miscellaneous

- Subcutaneous fat necrosis

- Arthalgia

Causes

Most common

- Biliary pancreatitis due to gallstones or constriction of ampulla of Vater in 40% of cases

- Alcohol in 30% of cases

- Idiopathic in 15-25% of cases

- Metabolic disorders: hereditary pancreatitis, hypercalcemia, elevated triglycerides, malnutrition

- Post-ERCP

- Abdominal trauma

- Penetrating ulcers

- Carcinoma of the head of pancreas, and other cancer

- Drugs: diuretics (e.g., thiazides, furosemide), gliptins (e.g., vildagliptin, sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin), tetracycline, sulfonamides, estrogens, azathioprine and mercaptopurine, pentamidine, salicylates, steroids, Depakote

- Infections: mumps, viral hepatitis, coxsackie B virus, cytomegalovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Ascaris

- Structural abnormalities: choledochocele, pancreas divisum

- Radiotherapy

- Autoimmune pancreatitis

- Severe hypertriglyceridemia[6]

Less common

- Scorpion venom

- Chinese liver fluke[7]

- Ischemia from bypass surgery

- Heart valve surgery[8]

- Fat necrosis

- Pregnancy

- Infections other than mumps, including varicella zoster[7]

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Valproic acid

- Cystic fibrosis

- Anorexia or bulimia

- Codeine phosphate reaction[9][10]

Pathology

Pathogenesis

Acute pancreatitis occurs when there is abnormal activation of digestive enzymes within the pancreas. This occurs through inappropriate activation of inactive enzyme precursors called zymogens (or proenzymes) inside the pancreas, most notably trypsinogen. Normally, trypsinogen is converted to its active form (trypsin) in the first part of the small intestine (duodenum), where the enzyme assists in the digestion of proteins. During an episode of acute pancreatitis, trypsinogen comes into contact with lysosomal enzymes (specifically cathepsin), which activate trypsinogen to trypsin. The active form trypsin then leads to further activation of other molecules of trypsinogen. The activation of these digestive enzymes lead to inflammation, edema, vascular injury, and even cellular death. The death of pancreatic cells occurs via two main mechanisms: necrosis, which is less organized and more damaging, or apoptosis, which is more controlled. The balance between these two mechanisms of cellular death is mediated by caspases which regulate apoptosis and have important anti-necrosis functions during pancreatitis: preventing trypsinogen activation, preventing ATP depletion through inhibiting polyADP-ribose polymerase, and by inhibiting the inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs). If, however, the caspases are depleted due to either chronic ethanol exposure or through a severe insult then necrosis can predominate.

Pathophysiology

The two types of acute pancreatitis are mild and severe, which are defined based on whether the predominant response to cell injury is inflammation (mild) or necrosis (severe). In mild pancreatitis, there is inflammation and edema of the pancreas. In severe pancreatitis, there is necrosis of the pancreas, and nearby organs may become injured.

As part of the initial injury there is an extensive inflammatory response due to pancreatic cells synthesizing and secreting inflammatory mediators: primarily TNF-alpha and IL-1. A hallmark of acute pancreatitis is a manifestation of the inflammatory response, namely the recruitment of neutrophils to the pancreas. The inflammatory response leads to the secondary manifestations of pancreatitis: hypovolemia from capillary permeability, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulations, renal failure, cardiovascular failure, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Histopathology

The acute pancreatitis (acute hemorrhagic pancreatic necrosis) is characterized by acute inflammation and necrosis of pancreas parenchyma, focal enzymic necrosis of pancreatic fat and vessel necrosis (hemorrhage). These are produced by intrapancreatic activation of pancreatic enzymes. Lipase activation produces the necrosis of fat tissue in pancreatic interstitium and peripancreatic spaces as well as vessel damage. Necrotic fat cells appear as shadows, contours of cells, lacking the nucleus, pink, finely granular cytoplasm. It is possible to find calcium precipitates (hematoxylinophilic). Digestion of vascular walls results in thrombosis and hemorrhage. Inflammatory infiltrate is rich in neutrophils. Due to the pancreas lacking a capsule, the inflammation and necrosis can extend to include fascial layers in the immediate vicinity of the pancreas.

Diagnosis

Acute pancreatitis is diagnosed using clinical history and physical examination, based on the presence of at least 2 of 3 criteria: abdominal pain, elevated serum lipase or amylase, and abdominal imaging findings consistent with acute pancreatitis.[11] Additional blood studies are used to identify organ failure, offer prognostic information, and determine if fluid resuscitation is adequate and whether ERCP is necessary.

- Blood investigations – complete blood count, kidney function tests, liver function, serum calcium, serum amylase and lipase

- Imaging – A triple phase abdominal CT and abdominal ultrasound are together considered the gold standard for the evaluation of acute pancreatitis. Other modalities including the abdominal x-ray lack sensitivity and are not recommended. An important caveat is that imaging during the first 12 hours may be falsely reassuring as the inflammatory and necrotic process usually requires 48 hours to fully manifest.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:[12]

- Perforated peptic ulcer

- Biliary colic

- Acute cholecystitis

- Pneumonia

- Pleuritic pain

- Myocardial infarction

Biochemical

- Elevated serum amylase and lipase levels, in combination with severe abdominal pain, often trigger the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. However, they have no role in assessing disease severity.

- Serum lipase rises 4 to 8 hours from the onset of symptoms and normalizes within 7 to 14 days after treatment.

- Serum amylase may be normal (in 10% of cases) for cases of acute or chronic pancreatitis (depleted acinar cell mass) and hypertriglyceridemia.

- Reasons for false positive elevated serum amylase include salivary gland disease (elevated salivary amylase), bowel obstruction, infarction, cholecystitis, and a perforated ulcer.

- If the lipase level is about 2.5 to 3 times that of amylase, it is an indication of pancreatitis due to alcohol.[13]

- Decreased serum calcium

- Glycosuria

Regarding selection on these tests, two practice guidelines state:

- "It is usually not necessary to measure both serum amylase and lipase. Serum lipase may be preferable because it remains normal in some nonpancreatic conditions that increase serum amylase including macroamylasemia, parotitis, and some carcinomas. In general, serum lipase is thought to be more sensitive and specific than serum amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis"[14]

- "Although amylase is widely available and provides acceptable accuracy of diagnosis, where lipase is available it is preferred for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis (recommendation grade A)"[15]

Most, but not all individual studies support the superiority of the lipase.[16] In one large study, there were no patients with pancreatitis who had an elevated amylase with a normal lipase.[17] Another study found that the amylase could add diagnostic value to the lipase, but only if the results of the two tests were combined with a discriminant function equation.[18]

While often quoted lipase levels of 3 or more times the upper-limit of normal is diagnostic of pancreatitis, there are also other differential diagnosis to be considered relating to this rise.[19]

Computed tomography

Regarding the need for computed tomography, practice guidelines state:

CT is an important common initial assessment tool for acute pancreatitis. Imaging is indicated during the initial presentation if:

- the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is uncertain

- there is abdominal distension and tenderness, fever >102 F (38,9 C), or leukocytosis

- there is a Ranson score > 3 or APACHE score > 8

- there is no improvement after 72 hours of conservative medical therapy

- there has been an acute change in status: fever, pain, or shock

CT is recommended as a delayed assessment tool in the following situations:

- acute change in status

- to determine therapeutic response after surgery or interventional radiologic procedure

- before discharge in patients with severe acute pancreatitis

Abdominal CT should not be performed before the first 12 hours of onset of symptoms as early CT (<12 hours) may result in equivocal or normal findings.

CT findings can be classified into the following categories for easy recall:

- Intrapancreatic – diffuse or segmental enlargement, edema, gas bubbles, pancreatic pseudocysts and phlegmons/abscesses (which present 4 to 6 wks after initial onset)

- Peripancreatic / extrapancreatic – irregular pancreatic outline, obliterated peripancreatic fat, retroperitoneal edema, fluid in the lessar sac, fluid in the left anterior pararenal space

- Locoregional – Gerota's fascia sign (thickening of inflamed Gerota's fascia, which becomes visible), pancreatic ascites, pleural effusion (seen on basal cuts of the pleural cavity), adynamic ileus, etc.

The principal value of CT imaging to the treating clinician is the capacity to identify devitalised areas of the pancreas which have become necrotic due to ischaemia. Pancreatic necrosis can be reliably identified by intravenous contrast-enhanced CT imaging,[20] and is of value if infection occurs and surgical or percutaneous debridement is indicated.

Magnetic resonance imaging

While computed tomography is considered the gold standard in diagnostic imaging for acute pancreatitis,[21] magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become increasingly valuable as a tool for the visualization of the pancreas, particularly of pancreatic fluid collections and necrotized debris.[22] Additional utility of MRI includes its indication for imaging of patients with an allergy to CT's contrast material, and an overall greater sensitivity to hemorrhage, vascular complications, pseudoaneurysms, and venous thrombosis.[23]

Another advantage of MRI is its utilization of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) sequences. MRCP provides useful information regarding the etiology of acute pancreatitis, i.e., the presence of tiny biliary stones (choledocholithiasis or cholelithiasis) and duct anomalies.[22] Clinical trials indicate that MRCP can be as effective a diagnostic tool for acute pancreatitis with biliary etiology as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, but with the benefits of being less invasive and causing fewer complications.[24][25]

Ultrasound

On abdominal ultrasonography, the finding of a hypoechoic and bulky pancreas is regarded as diagnostic of acute pancreatitis.

Treatment

Initial management of a patient with acute pancreatitis consists of supportive care with fluid resuscitation, pain control, nothing by mouth, and nutritional support.

Fluid replacement

Aggressive hydration at a rate of 5 to 10 mL/kg per hour of isotonic crystalloid solution (e.g., normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution) to all patients with acute pancreatitis, unless cardiovascular, renal, or other related comorbid factors preclude aggressive fluid replacement. In patients with severe volume depletion that manifests as hypotension and tachycardia, more rapid repletion with 20 mL/kg of intravenous fluid given over 30 minutes followed by 3 mL/kg/hour for 8 to 12 hours.[26][27]

Fluid requirements should be reassessed at frequent intervals in the first six hours of admission and for the next 24 to 48 hours. The rate of fluid resuscitation should be adjusted based on clinical assessment, hematocrit and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) values.

In the initial stages (within the first 12 to 24 hours) of acute pancreatitis, fluid replacement has been associated with a reduction in morbidity and mortality.[28][29][30][31]

Pain control

Abdominal pain is often the predominant symptom in patients with acute pancreatitis and should be treated with analgesics.

Opioids are safe and effective at providing pain control in patients with acute pancreatitis.[32] Adequate pain control requires the use of intravenous opiates, usually in the form of a patient-controlled analgesia pump. Hydromorphone or fentanyl (intravenous) may be used for pain relief in acute pancreatitis. Fentanyl is being increasingly used due to its better safety profile, especially in renal impairment. As with other opiates, fentanyl can depress respiratory function. It can be given both as a bolus as well as constant infusion. Meperidine has been historically favored over morphine because of the belief that morphine caused an increase in sphincter of Oddi pressure. However, no clinical studies suggest that morphine can aggravate or cause pancreatitis or cholecystitis.[33] In addition, meperidine has a short half-life and repeated doses can lead to accumulation of the metabolite normeperidine, which causes neuromuscular side effects and, rarely, seizures.

Bowel rest

In the management of acute pancreatitis, the treatment is to stop feeding the patient, giving them nothing by mouth, giving intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration, and sufficient pain control. As the pancreas is stimulated to secrete enzymes by the presence of food in the stomach, having no food pass through the system allows the pancreas to rest. Approximately 20% of patients have a relapse of pain during acute pancreatitis.[34] Approximately 75% of relapses occur within 48 hours of oral refeeding.

The incidence of relapse after oral refeeding may be reduced by post-pyloric enteral rather than parenteral feeding prior to oral refeeding.[34] IMRIE scoring is also useful.

Nutritional support

Recently, there has been a shift in the management paradigm from total parenteral nutrition (TPN) to early, post-pyloric enteral feeding (in which a feeding tube is endoscopically or radiographically introduced to the third portion of the duodenum). The advantage of enteral feeding is that it is more physiological, prevents gut mucosal atrophy, and is free from the side effects of TPN (such as fungemia). The additional advantages of post-pyloric feeding are the inverse relationship of pancreatic exocrine secretions and distance of nutrient delivery from the pylorus, as well as reduced risk of aspiration.

Disadvantages of a naso-enteric feeding tube include increased risk of sinusitis (especially if the tube remains in place greater than two weeks) and a still-present risk of accidentally intubating the trachea even in intubated patients (contrary to popular belief, the endotracheal tube cuff alone is not always sufficient to prevent NG tube entry into the trachea).

Oxygen

Oxygen may be provided in some patients (about 30%) if Pao2 levels fall below 70mm of Hg.

Antibiotics

Up to 20 percent of people with acute pancreatitis develop an infection outside the pancreas such as bloodstream infections, pneumonia, or urinary tract infections.[35] These infections are associated with an increase in mortality.[36] When an infection is suspected, antibiotics should be started while the source of the infection is being determined. However, if cultures are negative and no source of infection is identified, antibiotics should be discontinued.

Preventative antibiotics are not recommended in people with acute pancreatitis, regardless of the type (interstitial or necrotizing) or disease severity (mild, moderately severe, or severe)[11][37]

ERCP

In 30% of those with acute pancreatitis, no cause is identified. ERCP with empirical biliary sphincterotomy has an equal chance of causing complications and treating the underlying cause, therefore, is not recommended for treating acute pancreatitis.[38] If a gallstone is detected, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), performed within 24 to 72 hours of presentation with successful removal of the stone, is known to reduce morbidity and mortality.[39] The indications for early ERCP are:

- Clinical deterioration or lack of improvement after 24 hours

- Detection of common bile duct stones or dilated intrahepatic or extrahepatic ducts on abdominal CT

The risks of ERCP are that it may worsen pancreatitis, it may introduce an infection to otherwise sterile pancreatitis, and bleeding.

Surgery

Surgery is indicated for (i) infected pancreatic necrosis and (ii) diagnostic uncertainty and (iii) complications. The most common cause of death in acute pancreatitis is secondary infection. Infection is diagnosed based on 2 criteria

- Gas bubbles on CT scan (present in 20 to 50% of infected necrosis)

- Positive bacterial culture on FNA (fine needle aspiration, usually CT or US guided) of the pancreas.

Surgical options for infected necrosis include:

- Minimally invasive management – necrosectomy through small incision in skin (left flank) or abdomen

- Conventional management – necrosectomy with simple drainage

- Closed management – necrosectomy with closed continuous postoperative lavage

- Open management – necrosectomy with planned staged reoperations at definite intervals (up to 20+ reoperations in some cases)

Other measures

- Pancreatic enzyme inhibitors are proven not to work.[40]

- The use of octreotide has been shown not to improve outcomes.[41]

Classification by severity: prognostic scoring systems

Acute pancreatitis patients recover in majority of cases. Some may develop abscess, pseudocyst or duodenal obstruction. In 5 percent cases, it may result in ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome), DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation) Acute pancreatitis can be further divided into mild and severe pancreatitis.

Mostly the Ranson Criteria are used to determine severity of acute pancreatitis. In severe pancreatitis serious amounts of necrosis determine the further clinical outcome. About 20% of the acute pancreatitis are severe with a mortality of about 20%. This is an important classification as severe pancreatitis will need intensive care therapy whereas mild pancreatitis can be treated on the common ward.

Necrosis will be followed by a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and will determine the immediate clinical course. The further clinical course is then determined by bacterial infection. SIRS is the cause of bacterial (Gram negative) translocation from the patients colon.

There are several ways to help distinguish between these two forms. One is the above-mentioned Ranson Score.

In predicting the prognosis, there are several scoring indices that have been used as predictors of survival. Two such scoring systems are the Ranson criteria and APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) indices. Most,[42][43] but not all[44] studies report that the Apache score may be more accurate. In the negative study of the APACHE-II,[44] the APACHE-II 24-hour score was used rather than the 48-hour score. In addition, all patients in the study received an ultrasound twice which may have influenced allocation of co-interventions. Regardless, only the APACHE-II can be fully calculated upon admission. As the APACHE-II is more cumbersome to calculate, presumably patients whose only laboratory abnormality is an elevated lipase or amylase do not need assessment with the APACHE-II; however, this approach is not studied. The APACHE-II score can be calculated at www.sfar.org.

Practice guidelines state:

- 2006: "The two tests that are most helpful at admission in distinguishing mild from severe acute pancreatitis are APACHE-II score and serum hematocrit. It is recommended that APACHE-II scores be generated during the first 3 days of hospitalization and thereafter as needed to help in this distinction. It is also recommended that serum hematocrit be obtained at admission, 12 h after admission, and 24 h after admission to help gauge adequacy of fluid resuscitation."[14]

- 2005: "Immediate assessment should include clinical evaluation, particularly of any cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal compromise, body mass index, chest x ray, and APACHE II score"[15]

Ranson score

The Ranson score is used to predict the severity of acute pancreatitis. They were introduced in 1974.

At admission

- age in years > 55 years

- white blood cell count > 16000 cells/mm3

- blood glucose > 11.1 mmol/L (> 200 mg/dL)

- serum AST > 250 IU/L

- serum LDH > 350 IU/L

At 48 hours

- Calcium (serum calcium < 2.0 mmol/L (< 8.0 mg/dL)

- Hematocrit fall >10%

- Oxygen (hypoxemia PO2 < 60 mmHg)

- BUN increased by 1.8 or more mmol/L (5 or more mg/dL) after IV fluid hydration

- Base deficit (negative base excess) > 4 mEq/L

- Sequestration of fluids > 6 L

The criteria for point assignment is that a certain breakpoint be met at any time during that 48 hour period, so that in some situations it can be calculated shortly after admission. It is applicable to both gallstone and alcoholic pancreatitis.

Alternatively, pancreatitis can be diagnosed by meeting any of the following:[2]

Alternative Ranson score

Ranson's score of ≥ 8 Organ failure Substantial pancreatic necrosis (at least 30% glandular necrosis according to contrast-enhanced CT)

Interpretation If the score ≥ 3, severe pancreatitis likely. If the score < 3, severe pancreatitis is unlikely Or

Score 0 to 2 : 2% mortality Score 3 to 4 : 15% mortality Score 5 to 6 : 40% mortality Score 7 to 8 : 100% mortality

APACHE II score

"Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation" (APACHE II) score > 8 points predicts 11% to 18% mortality[14]

- Hemorrhagic peritoneal fluid

- Obesity

- Indicators of organ failure

- Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHG) or tachycardia > 130 beat/min

- PO2 <60 mmHg

- Oliguria (<50 mL/h) or increasing BUN and creatinine

- Serum calcium < 1.90 mmol/L (<8.0 mg/dL) or serum albumin <33 g/L (<3.2.g/dL)>

Balthazar score

Developed in the early 1990s by Emil J. Balthazar et al.,[45] the Computed Tomography Severity Index (CTSI) is a grading system used to determine the severity of acute pancreatitis. The numerical CTSI has a maximum of ten points, and is the sum of the Balthazar grade points and pancreatic necrosis grade points:

Balthazar grade

| Balthazar grade | Appearance on CT | CT grade points |

|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Normal CT | 0 points |

| Grade B | Focal or diffuse enlargement of the pancreas | 1 point |

| Grade C | Pancreatic gland abnormalities and peripancreatic inflammation | 2 points |

| Grade D | Fluid collection in a single location | 3 points |

| Grade E | Two or more fluid collections and / or gas bubbles in or adjacent to pancreas | 4 points |

Necrosis score

| Necrosis percentage | Points |

|---|---|

| No necrosis | 0 points |

| 0 to 30% necrosis | 2 points |

| 30 to 50% necrosis | 4 points |

| Over 50% necrosis | 6 points |

CTSI's staging of acute pancreatitis severity has been shown by a number of studies to provide more accurate assessment than APACHE II, Ranson, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level.[46][47][48] However, a few studies indicate that CTSI is not significantly associated with the prognosis of hospitalization in patients with pancreatic necrosis, nor is it an accurate predictor of AP severity.[49][50]

Glasgow score

The Glasgow score is valid for both gallstone and alcohol induced pancreatitis, whereas the Ranson score is only for alcohol induced pancreatitis. If a patient scores 3 or more it indicates severe pancreatitis and the patient should be considered for transfer to ITU. It is scored through the mnemonic, PANCREAS:

- P - PaO2 <8kPa

- A - Age >55-years-old

- N - Neutrophilia: WCC >15x10(9)/L

- C - Calcium <2 mmol/L

- R - Renal function: Urea >16 mmol/L

- E - Enzymes: LDH >600iu/L; AST >200iu/L

- A - Albumin <32g/L (serum)

- S - Sugar: blood glucose >10 mmol/L

BISAP score

Predicts mortality risk in pancreatitis with fewer variables than Ranson's criteria. Data should be taken from the first 24 hours of the patient's evaluation.

- BUN >25 mg/dL (8.9 mmol/L)

- Abnormal mental status with a Glasgow coma score <15

- Evidence of SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome)

- Patient age >60 years old

- Imaging study reveals pleural effusion

Patients with a score of zero had a mortality of less than one percent, whereas patients with a score of five had a mortality rate of 22 percent. In the validation cohort, the BISAP score had similar test performance characteristics for predicting mortality as the APACHE II score.[51] As is a problem with many of the other scoring systems, the BISAP has not been validated for predicting outcomes such as length of hospital stay, need for ICU care, or need for intervention.

Epidemiology

In the United States, the annual incidence is 18 cases of acute pancreatitis per 100,000 population, and it accounts for 220,000 hospitalizations in the US.[52] In a European cross-sectional study, incidence of acute pancreatitis increased from 12.4 to 15.9 per 100,000 annually from 1985 to 1995; however, mortality remained stable as a result of better outcomes.[53] Another study showed a lower incidence of 9.8 per 100,000 but a similar worsening trend (increasing from 4.9 in 1963–74) over time.[54]

In Western countries, the most common cause is alcohol, accounting for 65 percent of acute pancreatitis cases in the US, 20 percent of cases in Sweden, and 5 percent of those in the United Kingdom. In Eastern countries, gallstones are the most common cause of acute pancreatitis. The causes of acute pancreatitis also varies across age groups, with trauma and systemic disease (such as infection) being more common in children. Mumps is a more common cause in adolescents and young adults than in other age groups.

See also

- Canine pancreatitis

- Chronic pancreatitis

References

- Sommermeyer L (December 1935). "Acute Pancreatitis". American Journal of Nursing. 35 (12): 1157–1161. doi:10.2307/3412015. JSTOR 3412015.

- "Pancreatitis". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Symptoms & Causes of Pancreatitis". The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Sriram Bhat M (2018-10-31). SRB's Clinical Methods in Surgery. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 488–. ISBN 978-93-5270-545-0.

- Bassi C, Falconi M, Butturini G, Pederzoli P (2001). "Early complications of severe acute pancreatitis". In Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA (eds.). Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt.

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Thandra KC, Gaduputi V (December 2018). "Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis: updated review of current treatment and preventive strategies". Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology. 11 (6): 441–448. doi:10.1007/s12328-018-0881-1. PMID 29923163. S2CID 49311482.

- Rawla P, Bandaru SS, Vellipuram AR (June 2017). "Review of Infectious Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis". Gastroenterology Research. 10 (3): 153–158. doi:10.14740/gr858w. PMC 5505279. PMID 28725301.

- Chung JW, Ryu SH, Jo JH, Park JY, Lee S, Park SW, Song SY, Chung JB (January 2013). "Clinical implications and risk factors of acute pancreatitis after cardiac valve surgery". Yonsei Medical Journal. 54 (1): 154–9. doi:10.3349/ymj.2013.54.1.154. PMC 3521256. PMID 23225812.

- Hastier P, Buckley MJ, Peten EP, Demuth N, Dumas R, Demarquay JF, Caroli-Bosc FX, Delmont JP (November 2000). "A new source of drug-induced acute pancreatitis: codeine". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (11): 3295–8. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03213.x. PMID 11095359. S2CID 22261058.

- Moreno Escobosa MC, Amat López J, Cruz Granados S, Moya Quesada MC (2005). "Pancreatitis due to codeine". Allergologia et Immunopathologia. 33 (3): 175–7. doi:10.1157/13075703. PMID 15946633.

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS (September 2013). "American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 108 (9): 1400–15, 1416. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.218. PMID 23896955. S2CID 12610145.

- Bailey & Love's/24th/1123

- Gumaste VV, Dave PB, Weissman D, Messer J (November 1991). "Lipase/amylase ratio. A new index that distinguishes acute episodes of alcoholic from nonalcoholic acute pancreatitis". Gastroenterology. 101 (5): 1361–6. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(91)90089-4. PMID 1718808.

- Banks PA, Freeman ML, et al. (Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology) (October 2006). "Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (10): 2379–400. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. PMID 17032204. S2CID 1837007.

- UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis (May 2005). "UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis". Gut. 54 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3): iii1–9. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.057026. PMC 1867800. PMID 15831893.

- In support of the superiority of the lipase:

- Smith RC, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D (June 2005). "Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis?". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 75 (6): 399–404. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03391.x. PMID 15943725. S2CID 35768001.

- Treacy J, Williams A, Bais R, Willson K, Worthley C, Reece J, Bessell J, Thomas D (October 2001). "Evaluation of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 71 (10): 577–82. doi:10.1046/j.1445-2197.2001.02220.x. PMID 11552931. S2CID 30880859.

- Steinberg WM, Goldstein SS, Davis ND, Shamma'a J, Anderson K (May 1985). "Diagnostic assays in acute pancreatitis. A study of sensitivity and specificity". Annals of Internal Medicine. 102 (5): 576–80. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-102-5-576. PMID 2580467.

- Lin XZ, Wang SS, Tsai YT, Lee SD, Shiesh SC, Pan HB, Su CH, Lin CY (February 1989). "Serum amylase, isoamylase, and lipase in the acute abdomen. Their diagnostic value for acute pancreatitis". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 11 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1097/00004836-198902000-00011. PMID 2466075.

- Keim V, Teich N, Fiedler F, Hartig W, Thiele G, Mössner J (January 1998). "A comparison of lipase and amylase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis in patients with abdominal pain". Pancreas. 16 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1097/00006676-199801000-00008. PMID 9436862.

- Ignjatović S, Majkić-Singh N, Mitrović M, Gvozdenović M (November 2000). "Biochemical evaluation of patients with acute pancreatitis". Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 38 (11): 1141–4. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2000.173. PMID 11156345. S2CID 34932274.

- Sternby B, O'Brien JF, Zinsmeister AR, DiMagno EP (December 1996). "What is the best biochemical test to diagnose acute pancreatitis? A prospective clinical study". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 71 (12): 1138–44. doi:10.4065/71.12.1138. PMID 8945483.

- Smith RC, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D (June 2005). "Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis?". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 75 (6): 399–404. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03391.x. PMID 15943725. S2CID 35768001.

- Corsetti JP, Cox C, Schulz TJ, Arvan DA (December 1993). "Combined serum amylase and lipase determinations for diagnosis of suspected acute pancreatitis". Clinical Chemistry. 39 (12): 2495–9. doi:10.1093/clinchem/39.12.2495. PMID 7504593.

- Hameed AM, Lam VW, Pleass HC (February 2015). "Significant elevations of serum lipase not caused by pancreatitis: a systematic review". HPB. 17 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1111/hpb.12277. PMC 4299384. PMID 24888393.

- Larvin M, Chalmers AG, McMahon MJ (June 1990). "Dynamic contrast enhanced computed tomography: a precise technique for identifying and localising pancreatic necrosis". BMJ. 300 (6737): 1425–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.300.6737.1425. PMC 1663140. PMID 2379000.

- Arvanitakis M, Koustiani G, Gantzarou A, Grollios G, Tsitouridis I, Haritandi-Kouridou A, Dimitriadis A, Arvanitakis C (May 2007). "Staging of severity and prognosis of acute pancreatitis by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging-a comparative study". Digestive and Liver Disease. 39 (5): 473–82. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2007.01.015. PMID 17363349.

- Scaglione M, Casciani E, Pinto A, Andreoli C, De Vargas M, Gualdi GF (October 2008). "Imaging assessment of acute pancreatitis: a review". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 29 (5): 322–40. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2008.06.009. PMID 18853839.

- Miller FH, Keppke AL, Dalal K, Ly JN, Kamler VA, Sica GT (December 2004). "MRI of pancreatitis and its complications: part 1, acute pancreatitis". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 183 (6): 1637–44. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831637. PMID 15547203.

- Testoni PA, Mariani A, Curioni S, Zanello A, Masci E (June 2008). "MRCP-secretin test-guided management of idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis: long-term outcomes". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 67 (7): 1028–34. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.007. PMID 18179795.

- Khalid A, Peterson M, Slivka A (August 2003). "Secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance pancreaticogram to assess pancreatic duct outflow obstruction in evaluation of idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis: a pilot study". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 48 (8): 1475–81. doi:10.1023/A:1024747319606. PMID 12924639. S2CID 3066587.

- Gardner TB, Vege SS, Pearson RK, Chari ST (October 2008). "Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 6 (10): 1070–6. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.005. PMID 18619920.

- Haydock MD, Mittal A, Wilms HR, Phillips A, Petrov MS, Windsor JA (February 2013). "Fluid therapy in acute pancreatitis: anybody's guess". Annals of Surgery. 257 (2): 182–8. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827773ff. PMID 23207241. S2CID 46381021.

- Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines (2013). "IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis". Pancreatology. 13 (4 Suppl 2): e1–15. doi:10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063. PMID 24054878.

- Talukdar R, Swaroop Vege S (April 2011). "Early management of severe acute pancreatitis". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 13 (2): 123–30. doi:10.1007/s11894-010-0174-4. PMID 21243452. S2CID 38955726.

- Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Vege SS (August 2012). "Current controversies in fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review". Pancreas. 41 (6): 827–34. doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e31824c1598. PMID 22781906. S2CID 1864635.

- Gardner TB, Vege SS, Chari ST, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Levy MJ, Sarr MG (2009). "Faster rate of initial fluid resuscitation in severe acute pancreatitis diminishes in-hospital mortality". Pancreatology. 9 (6): 770–6. doi:10.1159/000210022. PMID 20110744. S2CID 5614093.

- Basurto Ona X, Rigau Comas D, Urrútia G (July 2013). "Opioids for acute pancreatitis pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD009179. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009179.pub2. PMID 23888429.

- Helm JF, Venu RP, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, Toouli J, Arndorfer RC (October 1988). "Effects of morphine on the human sphincter of Oddi". Gut. 29 (10): 1402–7. doi:10.1136/gut.29.10.1402. PMC 1434014. PMID 3197985.

- Petrov MS, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Cirkel GA, Brink MA, Gooszen HG (September 2007). "Oral refeeding after onset of acute pancreatitis: a review of literature". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 102 (9): 2079–84, quiz 2085. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01357.x. hdl:1874/26559. PMID 17573797. S2CID 11581054.

- Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Nieuwenhuijs VB, van Goor H, Dejong CH, Schaapherder AF, Gooszen HG (March 2009). "Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis". The British Journal of Surgery. 96 (3): 267–73. doi:10.1002/bjs.6447. PMID 19125434. S2CID 2226746.

- Wu BU, Johannes RS, Kurtz S, Banks PA (September 2008). "The impact of hospital-acquired infection on outcome in acute pancreatitis". Gastroenterology. 135 (3): 816–20. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.053. PMC 2570951. PMID 18616944.

- Jafri NS, Mahid SS, Idstein SR, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S (June 2009). "Antibiotic prophylaxis is not protective in severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Surgery. 197 (6): 806–13. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.08.016. PMID 19217608.

- Canlas KR, Branch MS (December 2007). "Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in acute pancreatitis". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (47): 6314–20. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6314. PMC 4205448. PMID 18081218.

- Apostolakos MJ, Papadakos PJ (2001). The Intensive Care Manual. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-006696-0.

- DeCherney AH, Lauren N (2003). Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-8385-1401-6.

- Peitzman AB, Schwab CW, Yealy DM, Fabian TC (2007). The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-6275-5.

- Larvin M, McMahon MJ (July 1989). "APACHE-II score for assessment and monitoring of acute pancreatitis". Lancet. 2 (8656): 201–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90381-4. PMID 2568529. S2CID 26047869.

- Yeung YP, Lam BY, Yip AW (May 2006). "APACHE system is better than Ranson system in the prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis". Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International. 5 (2): 294–9. PMID 16698595. Archived from the original on 2006-10-26.

- Chatzicostas C, Roussomoustakaki M, Vlachonikolis IG, Notas G, Mouzas I, Samonakis D, Kouroumalis EA (November 2002). "Comparison of Ranson, APACHE II and APACHE III scoring systems in acute pancreatitis". Pancreas. 25 (4): 331–5. doi:10.1097/00006676-200211000-00002. PMID 12409825. S2CID 27166241. (comment=this study used an Apache cutoff of >=10)

- Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, Ranson JH (February 1990). "Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis". Radiology. 174 (2): 331–6. doi:10.1148/radiology.174.2.2296641. PMID 2296641.

- Knoepfli AS, Kinkel K, Berney T, Morel P, Becker CD, Poletti PA (2007). "Prospective study of 310 patients: can early CT predict the severity of acute pancreatitis?" (PDF). Abdominal Imaging. 32 (1): 111–5. doi:10.1007/s00261-006-9034-y. PMID 16944038. S2CID 20809378.

- Leung TK, Lee CM, Lin SY, Chen HC, Wang HJ, Shen LK, Chen YY (October 2005). "Balthazar computed tomography severity index is superior to Ranson criteria and APACHE II scoring system in predicting acute pancreatitis outcome". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 11 (38): 6049–52. doi:10.3748/wjg.v11.i38.6049. PMC 4436733. PMID 16273623.

- Vriens PW, van de Linde P, Slotema ET, Warmerdam PE, Breslau PJ (October 2005). "Computed tomography severity index is an early prognostic tool for acute pancreatitis". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 201 (4): 497–502. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.269. PMID 16183486.

- Triantopoulou C, Lytras D, Maniatis P, Chrysovergis D, Manes K, Siafas I, Papailiou J, Dervenis C (October 2007). "Computed tomography versus Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score in predicting severity of acute pancreatitis: a prospective, comparative study with statistical evaluation". Pancreas. 35 (3): 238–42. doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180619662. PMID 17895844. S2CID 24245362.

- Mortelé KJ, Mergo PJ, Taylor HM, Wiesner W, Cantisani V, Ernst MD, Kalantari BN, Ros PR (October 2004). "Peripancreatic vascular abnormalities complicating acute pancreatitis: contrast-enhanced helical CT findings". European Journal of Radiology. 52 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.10.006. PMID 15380848.

- Papachristou GI, Muddana V, Yadav D, O'Connell M, Sanders MK, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC (February 2010). "Comparison of BISAP, Ranson's, APACHE-II, and CTSI scores in predicting organ failure, complications, and mortality in acute pancreatitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 105 (2): 435–41, quiz 442. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.622. PMID 19861954. S2CID 41655611.

- Whitcomb DC (May 2006). "Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (20): 2142–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp054958. PMID 16707751.

- Eland IA, Sturkenboom MJ, Wilson JH, Stricker BH (October 2000). "Incidence and mortality of acute pancreatitis between 1985 and 1995". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 35 (10): 1110–6. doi:10.1080/003655200451261. PMID 11099067.

- Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE (June 2004). "Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963-98: database study of incidence and mortality". BMJ. 328 (7454): 1466–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1466. PMC 428514. PMID 15205290.

External links

- Banks et al. Modified Marshall scoring system online calculator

- Pathology Atlas image.

- Parikh RP, Upadhyay KJ. Cullen's sign for acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis. Indian J Med Res [serial online] 2013 [cited 2013 Jul 4];137:1210 http://www.ijmr.org.in/text.asp?2013/137/6/1210/114397