Portal hypertension

Portal hypertension is abnormally increased portal venous pressure – blood pressure in the portal vein and its branches, that drain from most of the intestine to the liver.[3] Portal hypertension is defined as a hepatic venous pressure gradient greater than 5 mmHg.[4][5] Cirrhosis (a form of chronic liver failure) is the most common cause of portal hypertension; other, less frequent causes are therefore grouped as non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. When it becomes severe enough to cause symptoms or complications, treatment may be given to decrease portal hypertension itself or to manage its complications.

| Portal hypertension | |

|---|---|

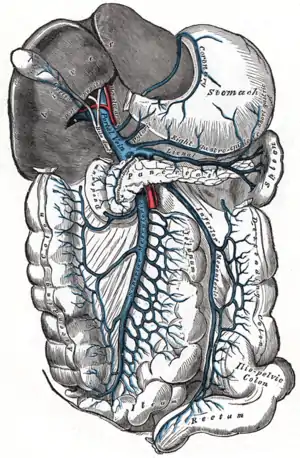

| |

| The portal vein and its tributaries | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Ascites[1] |

| Causes | Splenic vein thrombosis, stenosis of portal vein [2] |

| Diagnostic method | Ultrasonography[2] |

| Treatment | Portosystemic shunts, Nonselective beta-blockers[2] |

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of portal hypertension include:

- Ascites (free fluid in the peritoneal cavity),[1]

- Abdominal pain or tenderness [6] (when bacteria infect the ascites, as in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

- Increased spleen size (splenomegaly),[1] which may lead to lower platelet counts (thrombocytopenia)

- Anorectal varices

- Swollen veins on the anterior abdominal wall (sometimes referred to as caput medusae) [1]

In addition, a widened (dilated) portal vein as seen on a CT scan or MRI may raise the suspicion about portal hypertension. A cutoff value of 13 mm is widely used in this regard, but the diameter is often larger than this is in normal individuals as well.[7]

Causes

The causes for portal hypertension are classified as originating in the portal venous system before it reaches the liver (prehepatic causes), within the liver (intrahepatic) or between the liver and the heart (post-hepatic). The most common cause is cirrhosis (chronic liver failure). Other causes include:[1][8][9]

Prehepatic causes

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Splenic vein thrombosis

- Arteriovenous fistula (increased portal blood flow)

- Splenomegaly and/or hypersplenism (increased portal blood flow)

Hepatic causes

- Cirrhosis of any cause.

- alcohol use disorder

- chronic viral hepatitis

- biliary atresia

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Schistosomiasis

- Congenital hepatic fibrosis

- Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

- Fibrosis of space of Disse

- Granulomatous or infiltrative liver diseases (Gaucher disease, mucopolysaccharidosis, sarcoidosis, lymphoproliferative malignancies, amyloidosis, etc.)

- Toxicity (from arsenic, copper, vinyl chloride monomers, mineral oil, vitamin A, azathioprine, dacarbazine, methotrexate, amiodarone, etc.)

- Viral hepatitis

- Fatty liver disease

- Veno-occlusive disease

Posthepatic causes

- Inferior vena cava obstruction

- Right-sided heart failure, e.g. from constrictive pericarditis

- Budd–Chiari syndrome also known as hepatic vein thrombosis

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of portal hypertension is indicated by increased vascular resistance via different causes; additionally, hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts are activated. Increased endogenous vasodilators in turn promote more blood flow in the portal veins.[1][10]

Nitric oxide is an endogenous vasodilator and it regulates intrahepatic vascular tone (it is produced from L-arginine). Nitric oxide inhibition has been shown in some studies to increase portal hypertension and hepatic response to norepinephrine.[11]

Diagnosis

Mark.png.webp)

Ultrasonography (US) is the first-line imaging technique for the diagnosis and follow-up of portal hypertension because it is non-invasive, low-cost and can be performed on-site.[12]

A dilated portal vein (diameter of greater than 13 or 15 mm) is a sign of portal hypertension, with a sensitivity estimated at 12.5% or 40%.[13] On Doppler ultrasonography, a slow velocity of <16 cm/s in addition to dilatation in the main portal vein are diagnostic of portal hypertension.[14] Other signs of portal hypertension on ultrasound include a portal flow mean velocity of less than 12 cm/s, porto–systemic collateral veins (patent paraumbilical vein, spleno–renal collaterals and dilated left and short gastric veins), splenomegaly and signs of cirrhosis (including nodularity of the liver surface).[12]

The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) measurement has been accepted as the gold standard for assessing the severity of portal hypertension. Portal hypertension is defined as HVPG greater than or equal to 5 mm Hg and is considered to be clinically significant when HVPG exceeds 10 to 12 mm Hg.[15]

Treatment

The treatment of portal hypertension is divided into:

Portosystemic shunts

_in_progress.jpg.webp)

Selective shunts select non-intestinal flow to be shunted to the systemic venous drainage while leaving the intestinal venous drainage to continue to pass through the liver. The most well known of this type is the splenorenal.[16] This connects the splenic vein to the left renal vein thus reducing portal system pressure while minimizing any encephalopathy. In an H-shunt, which could be mesocaval (from the superior mesenteric vein to the inferior vena cava) or could be, portocaval (from the portal vein to the inferior vena cava) a graft, either synthetic or the preferred vein harvested from elsewhere on the patient's body, is connected between the superior mesenteric vein and the inferior vena cava. The size of this shunt will determine how selective it is.[17][18]

With the advent of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS), portosystemic shunts are less performed. TIPS has the advantage of being easier to perform and doesn't disrupt the liver's vascularity.[19]

Prevention of bleeding

Both pharmacological (non-specific β-blockers, nitrate isosorbide mononitrate, vasopressin such as terlipressin) and endoscopic (banding ligation) treatment have similar results. TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting) is effective at reducing the rate of rebleeding.[20]

The management of active variceal bleeding includes administering vasoactive drugs (somatostatin, octreotide), endoscopic banding ligation, balloon tamponade and TIPS.[20][2]

Ascites

The management of ascites needs to be gradual to avoid sudden changes in systemic volume status which can precipitate hepatic encephalopathy, kidney failure and death. The management includes salt restriction, diuretics (spironolactone), paracentesis,[21] and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).[22]

Hepatic encephalopathy

A treatment plan may involve lactulose, enemas, and use of antibiotics such as rifaximin, neomycin, vancomycin, and the quinolones. Restriction of dietary protein was recommended but this is now refuted by a clinical trial which shows no benefit. Instead, the maintenance of adequate nutrition is now advocated.[23]

References

- "Portal Hypertension. Learn about Portal Hypertension | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- "Portal Hypertension Medication: Somatostatin Analogs, Beta-Blockers, Nonselective, Vasopressin-Related, Vasodilators". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- "Portal Hypertension - Liver and Gallbladder Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- D'Souza, Donna. "Portal hypertension | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- "Portal hypertension | Disease | Overview | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Sheer, Todd A.; Runyon, Bruce A. (2005). "Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis". Digestive Diseases. 23 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1159/000084724. PMID 15920324. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Stamm, Elizabeth R.; Meier, Jeffrey M.; Pokharel, Sajal S.; Clark, Toshimasa; Glueck, Deborah H.; Lind, Kimberly E.; Roberts, Katherine M. (2016). "Normal main portal vein diameter measured on CT is larger than the widely referenced upper limit of 13 mm". Abdominal Radiology. 41 (10): 1931–1936. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0785-9. ISSN 2366-004X. PMID 27251734. S2CID 19845427.

- Bloom, S.; Kemp, W.; Lubel, J. (2015-01-01). "Portal hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management". Internal Medicine Journal. 45 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1111/imj.12590. ISSN 1445-5994. PMID 25230084. S2CID 45193610.

- Perkins, [edited by] Vinay Kumar, Abul K. Abbas, Jon C. Aster; artist, James A. (2013-01-01). Robbins basic pathology (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 608. ISBN 978-1-4377-1781-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)2013 - "Portal Hypertension: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy". 2018-10-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Maruyama, Hitoshi; Yokosuka, Osamu (2012). "Pathophysiology of Portal Hypertension and Esophageal Varices". International Journal of Hepatology. 2012: 895787. doi:10.1155/2012/895787. PMC 3362051. PMID 22666604.

- Jaime Bosch, MD, PhD; Annalisa Berzigotti, MD, PhD; Susana Seijo, MD; Enric Reverter, MD (2013-01-28). "Assessing Portal Hypertension in Liver Diseases: Noninvasive Techniques to Assess Portal Hypertension".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Al-Nakshabandi NA (2006). "The role of ultrasonography in portal hypertension". Saudi J Gastroenterol. 12 (3): 111–7. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.29750. PMID 19858596.

- Iranpour, Pooya; Lall, Chandana; Houshyar, Roozbeh; Helmy, Mohammad; Yang, Albert; Choi, Joon-Il; Ward, Garrett; Goodwin, Scott C (2016). "Altered Doppler flow patterns in cirrhosis patients: an overview". Ultrasonography. 35 (1): 3–12. doi:10.14366/usg.15020. ISSN 2288-5919. PMC 4701371. PMID 26169079.

- Al-Busafi SA, McNabb-Baltar J, Farag A, Hilzenrat N (2012). "Clinical manifestations of portal hypertension". Int J Hepatol. 2012: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2012/203794. PMC 3457672. PMID 23024865.

- Shah, Omar Javed; Robbani, Irfan (2005-01-01). "A Simplified Technique of Performing Splenorenal Shunt (Omar's Technique)". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 32 (4): 549–554. ISSN 0730-2347. PMC 1351828. PMID 16429901.

- Moore, Wesley S. (2012-11-23). Vascular and Endovascular Surgery: A Comprehensive Review. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 851. ISBN 978-1455753864.

- Yin, Lanning; Liu, Haipeng; Zhang, Youcheng; Rong, Wen (2013). "The Surgical Treatment for Portal Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". ISRN Gastroenterology. 2013: 464053. doi:10.1155/2013/464053. PMC 3594950. PMID 23509634.

- Pomier-Layrargues, Gilles; Bouchard, Louis; Lafortune, Michel; Bissonnette, Julien; Guérette, Dave; Perreault, Pierre (2012). "The Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt in the Treatment of Portal Hypertension: Current Status". International Journal of Hepatology. 2012: 167868. doi:10.1155/2012/167868. PMC 3408669. PMID 22888442.

- Bari, Khurram; Garcia-Tsao, Guadalupe (2012-03-21). "Treatment of portal hypertension". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (11): 1166–1175. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1166. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 3309905. PMID 22468079.

- Dib, Nina; Oberti, Frédéric; Calès, Paul (2006-05-09). "Current management of the complications of portal hypertension: variceal bleeding and ascites". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 174 (10): 1433–1443. doi:10.1503/cmaj.051700. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 1455434. PMID 16682712.

- Runyon, BA; AASLD (April 2013). "Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012". Hepatology. 57 (4): 1651–3. doi:10.1002/hep.26359. PMID 23463403.

- "Hepatic Encephalopathy. Free Medical information". www.patient.info.

Further reading

- Garbuzenko D.V., Arefyev N.O., Belov D.V. Restructuring of the vascular bed in response to hemodynamic disturbances in portal hypertension. World J. Hepatol. 2016; 8 (36): 1602-1609.

- Garbuzenko D.V., Arefyev N.O., Belov D.V. Mechanisms of adaptation of the hepatic vasculature to the deteriorating conditions of blood circulation in liver cirrhosis. World J. Hepatol. 2016; 8 (16): 665-672.

- Garbuzenko D.V. Current approaches to the management of patients with liver cirrhosis who have acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016; 32 (3): 467-475.

- Garbuzenko D.V. Contemporary concepts of the medical therapy of portal hypertension under liver cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015; 21 (20): 6117-6126.

- García-Pagán, Juan-Carlos; Gracia-Sancho, Jorge; Bosch, Jaume (2012). "Functional aspects on the pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis – Journal of Hepatology". Journal of Hepatology. 57 (2): 458–461. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.007. PMID 22504334. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- Rossi, Plinio (2012-12-06). Portal Hypertension: Diagnostic Imaging and Imaging-Guided Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783642571169.

- Imanieh, Mohammad Hadi; Dehghani, Seyed Mohsen; Khoshkhui, Maryam; Malekpour, Abdorrasoul (2012-10-01). "Etiology of Portal Hypertension in Children:A Single Center's Experiences". Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases. 4 (4): 206–210. ISSN 2008-5230. PMC 3990125. PMID 24829658.