Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (Hungarian: [ˈimrɛ ˈnɒɟ]; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (de facto Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 against the Soviet-backed government, for which he was sentenced to death and executed two years later.

Imre Nagy | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

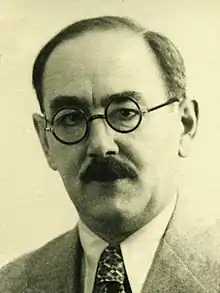

Nagy in 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People's Republic | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office 24 October 1956 – 4 November 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | List

| ||||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary | Ernő GerőJános Kádár | ||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | András Hegedűs | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | János Kádár | ||||||||||||||||||

| In office 4 July 1953 – 18 April 1955 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | List

| ||||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary | Mátyás Rákosi | ||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Mátyás Rákosi | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | András Hegedűs | ||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office 2 November 1956 – 4 November 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Imre Horváth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Imre Horváth | ||||||||||||||||||

| Speaker of the National Assembly | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 September 1947 – 8 June 1949 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Árpád Szabó | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Károly Olt | ||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of the Interior | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 November 1945 – 20 March 1946 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Zoltán TildyFerenc Nagy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Ferenc Erdei | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | László Rajk | ||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Agriculture | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 December 1944 – 15 November 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Béla Miklós | ||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Fidél Pálffy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Béla Kovács | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 7 June 1896 Kaposvár, Somogy County, Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 16 June 1958 (aged 62) Budapest, Hungarian People's Republic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Hungarian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union Social Democratic Party of Hungary Hungarian Communist Party, Hungarian Working People's Party, Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | Mária Égető (1902–1978)

(m. 1925) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Erzsébet | ||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Austro-Hungarian Army (Royal Hungarian Honvéd) (1914–1916) Red Army (1918) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1914–1916 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Corporal | ||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | 17th Royal Hungarian Honvéd Infantry Regiment (1915) 19th Machine Gun Battalion (1916) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | World War I

| ||||||||||||||||||

Nagy was a committed communist from soon after the Russian Revolution, and through the 1920s he engaged in underground party activity in Hungary. Living in the Soviet Union from 1930, he served the Soviet NKVD secret police as an informer from 1933 to 1941, denouncing over 200 colleagues, who were then purged and arrested and 15 of whom were executed. Nagy returned to Hungary shortly before the end of World War II, and served in various offices as the Hungarian Working People's Party (MDP) took control of Hungary in the late 1940s and the country entered the Soviet sphere of influence. He served as Interior Minister of Hungary from 1945 to 1946. Nagy became prime minister in 1953 and attempted to relax some of the harshest aspects of Mátyás Rákosi's Stalinist regime, but was subverted and eventually forced out of the government in 1955 by Rákosi's continuing influence as General Secretary of the MDP. Nagy remained popular with writers, intellectuals, and the common people, who saw him as an icon of reform against the hard-line elements in the Soviet-backed regime.

The outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution on 23 October 1956 saw Nagy elevated to the position of Prime Minister on 24 October as a central demand of the revolutionaries and common people. Nagy's reformist faction gained full control of the government, admitted non-communist politicians, dissolved the ÁVH secret police, promised democratic reforms, and unilaterally withdrew Hungary from the Warsaw Pact on 1 November. The Soviet Union launched a massive military invasion of Hungary on 4 November, forcibly deposing Nagy, who fled to the Embassy of Yugoslavia in Budapest. Nagy was lured out of the Embassy under false promises on 22 November, but was arrested and deported to Romania. On 16 June 1958, Nagy was tried and executed for treason alongside his closest allies, and his body was buried in an unmarked grave.

In June 1989, Nagy and other prominent figures of the 1956 Revolution were rehabilitated and reburied with full honours, an event that played a key role in the collapse of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party regime.

Early life and World War I

Imre Nagy was born prematurely on 7 June 1896 in the town of Kaposvár in the Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary, to a small-town family of peasant origin.[1] His father, József Nagy (1869–1929), was a Lutheran and a carriage driver for the lieutenant-general of Somogy county. His mother, Rozália Szabó (1877–1969), served as a maid for the lieutenant-general's wife.[1] They both had left the countryside in their youth to work in Kaposvár.[1] Nagy and Szabó married in January 1896.[1] In 1902, József became a postal worker and began building a house for the family in 1907 but lost his job in 1911 and had to sell the house.[2] He was an unskilled worker for the rest of his life.[2]

In 1904 Nagy's family moved to Pécs before returning to Kaposvár the following year. Nagy attended a gymnasium in Kaposvár from 1907 to 1912, performing poorly.[3] The gymnasium cancelled his tuition due to his lack of accomplishment and funding.[3] He apprenticed as a locksmith in a small metalworking firm in Kaposvár, before moving to a factory for agricultural machinery in Losonc in northern Hungary in 1912. He returned to Kaposvár in 1913 and was given a journeyman's certificate as a metal fitter in 1914. He abandoned the job in the summer of 1914 and became a clerk at a lawyer's office, while simultaneously attending a commercial high school in Kaposvár, where his student performance was good.[3]

After the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914, Nagy was called up for military service in the Austro-Hungarian Army in December 1914 and found fit for service.[4] He reported for duty at the 17th Royal Hungarian Honvéd Infantry Regiment in May 1915, after the end of the school year and before he had graduated.[4] After three months of basic training in Székesfehérvár, his unit was sent to the Italian Front in August 1915, where he was wounded in his leg at the Third Battle of the Isonzo. After convalescing in a field hospital, he was trained as a machine gunner in the 19th Machine Gun Battalion, promoted to corporal and sent to the Eastern Front in the summer of 1916.[5]

Nagy was wounded in the leg by shrapnel and taken prisoner by the Imperial Russian Army during the Brusilov Offensive in Galicia on 29 July 1916.[6][7] After healing his leg wound in a field hospital, he was taken first to Darnitsa, then to Ryazan and finally on a train transport to Siberia.[8]

Early political career

In captivity in Camp Berezovka near Lake Baikal in Siberia he participated in a Marxist discussion group until 1917.[9] In 1918, he joined the Communist (Social Democratic) Party of the Foreign Workers of Siberia, a sub-group of the Russian Communist Party.[9][7] He fought in the ranks of the Red Army from February to September 1918 during the Russian Civil War.[9] Some sources, including the so-called "Yurovsky Document" allege Nagy and his unit were tasked with guarding the former Russian Imperial Family in Yekaterinburg.[10] Though some historians have speculated Nagy himself was among the men in the firing squad that executed the Romanovs, Ivan Plotnikov, history professor at the Ural State University, stated per his research that the executioners were Yakov Yurovsky, Grigory Nikulin, Mikhail Medvedev (Kudrin), Peter Ermakov, Stepan Vaganov, Alexey Kabanov, Pavel Medvedev, V. N. Netrebin, and Y. M. Tselms. The White Army investigator Nikolai Sokolov claimed that the executions of the Imperial Family was carried out by a group of "Latvians led by a Jew".[11] However, in light of Plotnikov's research, the group that carried out the execution consisted almost entirely of ethnic Russians (Nikulin, Kudrin, Ermakov, Vaganov, Kabanov, Medvedev and Netrebin) with the participation of one Jew (Yurovsky) and possibly, one Latvian (Tselms).[12] Allegations of Nagy's presence at the Ipatiev House remains a controversial matter among biographers, and has contributed to his divisive legacy in modern Hungary.

Nagy and his unit were later encircled and he was ultimately taken prisoner by the Czechoslovak Legion in early September 1918.[9] He escaped captivity and spent the period until February 1920 holding odd jobs in White-controlled territory near Lake Baikal.[9] The Red Army reached Irkutsk on 7 February 1920, ending Nagy's participation in the Civil War.[9] On 12 February 1920 he became a candidate member of the Russian Communist Party and a full-time member on 10 May.[13] He served the rest of 1920 as a clerk for the communist Cheka secret police on matters related to prisoners of war.[13]

After a month of training by the Cheka in subversive activities, the Hungarian Communist Party (KMP) sent Nagy along with 277 other Hungarian communists to Hungary in April 1921 to build up an underground conspiratorial network in a country where the Communist Party had been banned since 1919.[14][7] Nagy reached Kaposvár in late May 1921.[14] Upon arrival, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Hungary (MSZDP).[15] After working temporary jobs in the rest of 1921 and early 1922, he joined the First Hungarian Insurance Company and became an office worker in Kaposvár.[16] He became severely overweight around this time.[17] He helped to build up the socialist movement in his hometown, to his parents' disapproval.[17] He became secretary of the MSZDP's local branch in 1924.[18] He was expelled from the party for advocating revolution and was placed under police surveillance.[18] He married Mária Égető on 28 November 1925.[18]

In January 1926, Nagy and István Sinkovics established the Kaposvár office of the Socialist Workers’ Party of Hungary (MSZMP), a semi-communist left-wing splinter group from the MSZDP.[19] Nagy was successful in gaining 700 voters for the MSZMP Kaposvár parliamentary candidate, one of the party's few successes in the countryside west of Budapest.[20] By this time Nagy had begun to prioritize his interest in agriculture over political leadership and rejected an offer from communist cadres from Vienna to build up the illegal KMP in western Hungary.[21] The MSZMP in Kaposvár was prohibited and Nagy was fired from his insurance job in February 1927 and arrested on 27 February.[21] He was released after two months in prison.[21] While under police surveillance, Nagy found a job as an agent for the Phoenix Insurance Company.[22] He was arrested again in December 1927 for three days and was called to Vienna by the KMP, arriving in March 1928.[22] He became head of the KMP's agrarian section and was sent back to Hungary in September 1928 under a false identity to build up underground communist networks.[23] His efforts were largely a failure, his largest successes being the publishing of three issues of a small journal and his avoidance of arrest.[23] His advocacy of legal political activity over the party's preference for largely impotent clandestine work in villages was dismissed as "right-deviancy" by the ultra-left KMP leadership.[24]

Years in Moscow

In December 1929, he traveled to the Soviet Union, arriving in Moscow in February 1930 to participate in the KMP's second congress.[25] He rejoined the Communist Party, also becoming a Soviet citizen. He was engaged in agricultural research at the International Agrarian Institute for six years, but also worked in the Hungarian section of the Comintern.[7] He was expelled from the party on 8 January 1936 and worked for the Soviet Statistical Service from the summer of 1936 onward.[26] Under the codename "Volodia", Nagy served the NKVD secret police as an informer from 1933 to 1941, giving up the names of over 200 comrades, mostly from the Agrarian Institute, who were then arrested and in at least 15 cases executed by the secret police.[27][28][29] The NKVD praised him as a "qualified agent, who shows great initiative and an ability to approach people".[28] The support that Nagy received from the Soviet leadership after the Second World War was to some extent a result of his loyal service as a foreigner and denouncer to the NKVD.[27]

Minister in Communist Hungary

After the Second World War, Nagy returned to Hungary. He was the Minister of Agriculture in the government of Béla Miklós de Dálnok, delegated by the Hungarian Communist Party. He distributed land among the peasant population. In the next government, led by Tildy, he was the Minister of Interior. At this period he played an active role in the expulsion of the Hungarian Germans.[30]

In the communist government, he served as Minister of Agriculture and in other posts. He was also Speaker of the National Assembly of Hungary from 1947 to 1949, a largely ceremonial position.[31] In 1951, he signed, with the rest of the Politburo, the note ordering János Kádár's arrest, resulting in Kádár's torture and sentencing to life in prison after a show trial.[28]

After two years as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People's Republic (1953–1955), during which he promoted his "New Course" in Socialism, Nagy fell out of favour with the Soviet Politburo. He was deprived of his Hungarian Central Committee, Politburo, and all other Party functions and, on 18 April 1955, he was sacked as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[32]

1956 Revolution

Following Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" denouncing the crimes of Stalin on 25 February 1956, dissent began to grow in Eastern Bloc against the ruling Stalinist-era party leaders. In Hungary, Mátyás Rákosi—who self-styled as "Stalin's greatest disciple"—came under increasingly intense criticism for his policies from both the Party and general populace, with more and more prominent voices calling for his resignation. This public criticism often took the form of the Petőfi Circle—a debating club established by the DISZ student youth union to discuss Communist policy—which soon became one of the foremost outlets of dissent against the regime. While Nagy himself never attended a Petőfi Circle meeting, he was kept well informed of events by his close associates Miklós Vásárhelyi and Géza Losonczy, who informed him of the vast popular support expressed for him at the meetings and the widespread desire for his restoration to the leadership.[33]

In the face of widespread public pressure on Rákosi, the Soviets forced the unpopular leader to resign from power on 18 July 1956 and leave for the Soviet Union. However, they replaced him with his equally hard-line second in command Ernő Gerő, a change which did little to mollify public dissent. Nagy was a prominent guest at the 6 October reburial of former secret police chief László Rajk, who had been purged by the Rákosi regime and later rehabilitated. He was readmitted to the Party on 13 October in the midst of growing revolutionary fervor. On 22 October, students from the Technical University in Budapest compiled a list of sixteen national policy demands, the third of which was Nagy's restoration to the premiership.

In the afternoon of 23 October, students and workers gathered in Budapest for a massive opposition demonstration arranged by the Technical University students, chanting—among other things—slogans of support for Imre Nagy. While the ex-premier sympathized with their reformist demands, he was hesitant to support the movement, believing it to be too radical in its demands. While he was in favor of changes to the system, he preferred those to be made within the framework of his "New Course" of 1953–55 and not a revolutionary upheaval. He also feared that the demonstration was a provocation by Gerő and Hegedüs to frame him as inciting rebellion and to crack down on the opposition.

His associates ultimately convinced him to travel to the Parliament Building and give a speech to the demonstrators to calm the unrest. While no accurate record of this speech exists, it did not have its intended effect; Nagy essentially told the protesters to go home and let the Party handle things. The demonstrations soon escalated into a full-scale revolt as ÁVH secret policemen opened fire on the protesting citizens. Hungarian soldiers sent to crush the demonstrators instead sided with them, and Gerő soon called in Soviet intervention.

Early in the morning of 24 October, Nagy was renamed as Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People's Republic again, in an attempt to appease the populace. However, he was initially isolated within the government, and powerless to stop the Soviet invasion of the capital that day. The decision to call in Soviet forces had already been made by Gerő and outgoing Prime Minister András Hegedüs the previous night, but many suspected that Nagy had signed the order.[34] This perception was not helped by the fact that Nagy declared martial law on that same day and offered an "amnesty" to all rebels who laid down their arms, weakening the public's trust in him. The next day (25 October) he announced he would begin negotiations on the withdrawal of Soviet troops after order was restored. On 26 October, he began to meet with delegations from the Writers' Union and student groups, as well as from the Borsod Workers' Council in Miskolc.

On 27 October, Nagy announced a major reformation of his government, to include several non-communist politicians including former president Zoltán Tildy as a Minister of State. At negotiations with Soviet representatives Anastas Mikoyan and Mikhail Suslov, Nagy and the Hungarian government delegation pushed for a ceasefire and political solution.

In the morning of 28 October, Nagy successfully prevented a massive attack on the main rebel strongholds at the Corvin Cinema and Kilián Barracks by Soviet troops and pro-regime Hungarian units. He negotiated a ceasefire with the Soviets, which came into effect at 12:15 and fighting began to die down across the city and country. Later that day, he gave a speech on the radio assessing the events as a "national democratic movement," proclaiming his full support of the Revolution and agreeing to fulfill some of the public's demands.[35] He announced the dissolution of the ÁVH and his intention to negotiate the full withdrawal of Soviet troops from the city. Nagy also supported the creation of a National Guard, a force of combined soldiers and armed civilians to maintain order amidst the chaos of the Revolution.

On 29 October, as fighting died down across Budapest and Soviet troops began to withdraw, Nagy moved his office from the Party headquarters to the Parliament Building. He also began to meet and negotiated with several representatives of the armed groups that day, as well as the representatives of the workers' councils that had been formed over the course of the previous week.

By 30 October, Nagy's reformist faction had gained full control of the Hungarian government. Ernő Gerő and the other Stalinist hard-liners had left for the Soviet Union, and Nagy's government announced its intent to restore a multi-party system based on the coalition parties from 1945.[36] Throughout this period, Nagy remained steadfastly committed to Marxism; but his conception of Marxism was as "a science that cannot remain static", and he railed against the "rigid dogmatism" of "the Stalinist monopoly".[37] He did not intend a full return to multi-party liberal democracy but a limited one within a socialist framework, and was willing to allow the function of the pre-1948 coalition parties.[38]

Nagy was appointed to the temporary leadership committee of the newly formed Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which replaced the disintegrated Hungarian Working People's Party on 31 October. This was originally intended as a "national-communist" party that would preserve the gains of the Revolution. However, at a meeting of the Soviet Politburo that day, the Kremlin leaders decided that the Revolution had gone too far and needed to be crushed. On the night of 31 October – 1 November, Soviet troops began crossing back into Hungary, contrary to their declaration of 30 October expressing willingness to withdraw from the country entirely. Nagy protested this action to Soviet Ambassador Yuri Andropov; the latter replied that the new troops were only there to cover the full withdrawal and protect Soviet citizens living in Hungary. This likely prompted Nagy to make his most controversial decision. In response to a major demand of the revolutionaries, he announced Hungary's withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact and appealed through the UN for the great powers, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, to recognise Hungary's status as a neutral state.[39] Late that night, General Secretary János Kádár went to the Soviet embassy, and the next day he was taken to Moscow.

Between 1–3 November, Nikita Khrushchev traveled to various Warsaw Pact countries as well as to Yugoslavia to inform them of his plans to attack Hungary. On the advice of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, he selected the then-Party General Secretary János Kádár as the country's new leader on 2 November, and was willing to let Nagy remain in the government if he cooperated. On 3 November, Nagy formed a new government, this time with a Communist minority. It included members of the Communists, Independent Smallholders' Party, Peasants' Party, and Social Democrats. However, it would only be in office for less than a day.

In the early morning hours of 4 November, the USSR launched "Operation Whirlwind," a massive military attack on Budapest and on rebel strongholds throughout the country. Nagy made a dramatic announcement to the country and the world about this operation.[40] However, to minimize damage he ordered the Hungarian Army not to resist the invaders.[41] Soon after, he fled to the Yugoslav Embassy, where he and many of his followers were given sanctuary.

In spite of a written safe conduct of free passage by János Kádár, on 22 November, Nagy was arrested by the Soviet forces as he was leaving the Yugoslav Embassy and taken to Snagov, Romania.[42][43]

Secret trial and execution

Subsequently, the Soviets returned Nagy to Hungary, where he was secretly charged with organizing the overthrow of the Hungarian People's Republic and with treason. In prison, Nagy was object of continuous tortures of part of officials.[44] Nagy was secretly tried, found guilty, sentenced to death and executed by hanging in June 1958.[45] His trial and execution were made public only after the sentence had been carried out.[46] According to Fedor Burlatsky, a Kremlin insider, Nikita Khrushchev had Nagy executed, "as a lesson to all other leaders in socialist countries".[47] American journalist John Gunther described the events leading to Nagy's death as "an episode of unparalleled infamy".[48]

Nagy was buried, along with his co-defendants, in the prison yard where the executions were carried out and years later was removed to a distant corner (section 301) of the New Public Cemetery, Budapest,[49] face-down, and with his hands and feet tied with barbed wire. Next to his grave stands a memorial bell inscribed in Latin, Hungarian, German and English. The Latin reads: "Vivos voco / Mortuos plango / Fulgura frango", which is translated as: "I call the living, I mourn the dead, I break the thunderbolts".[50]

Memorials and political rehabilitation

During the time when the Stalinist leadership of Hungary would not permit his death to be commemorated, or permit access to his burial place, a cenotaph in his honour was erected in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris on 16 June 1988.[51]

In 1989, Imre Nagy was rehabilitated and his remains reburied on the 31st anniversary of his execution in the same plot after a funeral organised in part by the democratic opposition to the country's Stalinist regime.[52] Over 200,000 people are estimated to have attended Nagy's reinterment. The occasion of Nagy's funeral was an important factor in the end of the communist government in Hungary.[53]

On 28 December 2018, a popular statue of Nagy inaugurated in 1996 was removed from central Budapest to a less central location, in order to make way to a reconstructed memorial to the victims of the 1919 Red Terror that originally stood in the same place from 1934 to 1945, during the Miklós Horthy's pro-nazi regime. Opposition parties, mainly liberal, socialist and the remaining communists accused Viktor Orbán's right-wing government of historical revisionism, his supporters however, argued that the initiative was taken as an attempt to restore the city landscape to its pre-World War Two form and to "erase the traces of the communist era".[54][55][56][57]

Writings

The collected writings of Nagy, most of which he wrote after his dismissal as Chairman of the Council of Ministers in April 1955, were smuggled out of Hungary and published in the West under the title Imre Nagy on Communism.[58]

Family

Nagy was married to Mária Égető. The couple had one daughter, Erzsébet Nagy (1927–2008), a Hungarian writer and translator.[59] Erzsébet Nagy married Ferenc Jánosi. Imre Nagy did not object to his daughter's romance and eventual marriage to a Protestant minister, attending their religious wedding ceremony in 1946 without Politburo permission. In 1982, Erzsébet Nagy married János Vészi.[29]

Nagy in film and the arts

In 2003 and 2004, the Hungarian director Márta Mészáros produced a film based on Nagy's life after the revolution, entitled A temetetlen halott (English: The Unburied Body) (IMDb entry).

Nagy is mentioned and seen in the 2006 movie Children of Glory.

The rehabilitation of Nagy after 40 years condemnation is referred to by a character in the 1991 Malayalam film Sandhesam as part of an anti-communist rhetoric.

See also

- Hungarian Revolution of 1956

- Governments of Imre Nagy

- End of Communism in Hungary

Citations

- Rainer 2009, p. 1.

- Rainer 2009, p. 2.

- Rainer 2009, p. 3.

- Rainer 2009, p. 4.

- Rainer 2009, p. 5.

- Rainer 2009, p. 6.

- Granville 2004, p. 21.

- Rainer 2009, p. 7.

- Rainer 2009, p. 8.

- "Yurovsky Document". Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- Sokolov, N. A. Chapter XV: Surrounding the royal family by security officers // Murder of the royal family.

- Plotnikov, I (2003). "About the team of the executioners of the royal family and its ethnic composition". Ural Magazine.

- Rainer 2009, p. 9.

- Rainer 2009, p. 10.

- Rainer 2009, p. 12.

- Rainer 2009, pp. 12–13.

- Rainer 2009, p. 13.

- Rainer 2009, p. 14.

- Rainer 2009, p. 15.

- Rainer 2009, pp. 15–16.

- Rainer 2009, p. 16.

- Rainer 2009, p. 17.

- Rainer 2009, p. 18.

- Rainer 2009, p. 20.

- Rainer 2009, p. 21.

- Rainer 2009, p. 28.

- Rainer 2009, p. 29.

- Granville 2004, p. 23.

- Gati, Charles (2006). Failed Illusions: Moscow, Washington, Budapest and the 1956 Hungarian Revolt, p. 42. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-5606-6.

- (hu) Imre Nagy's unknown life, in Magyar Narancs

- Rainer 2009, p. 45.

- Rainer 2009, p. 82.

- Hall, Simon. 1956: The World in Revolt. New York: Pegasus Books, 2015. p. 185

- János Rainer M. Imre Nagy. Political biography 1953–1958. (Volume II) 1956 Institute, Budapest, 1999, 248–249.

- Chronicle 1956 . Editor-in-Chief: Louis Isaac. Ed .: Gyula Stemler. Kossuth Publisher – Tekintet Alapítvány, Bp., 2006. p.

- Rainer 2009, p. 118.

- Stokes, Gale. From Stalinism to Pluralism. pp. 82–83

- Sándor Révész: Communists in the Revolution, Gábor Gyáni – Rainer M. János (ed.): Thousand Ninety-Seventy in the New Historical Literature, Symbol and Idea History of the Revolution , p. 2007. 1956 Institute, Budapest, ISBN 9789639739024

- Gyorgy Litvan, The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, (Longman House: New York, 1996), 55–59

- Ferenc Donáth: Imre Nagy, Radio News of 4 November 1956 and the Geneva Conventions. Our past, 2007/1. s. 150–168.

- Hall, Simon. 1956: The World in Revolt. New York: Pegasus Books, 2015. pp. 346–347

- Rainer 2009, p. 142.

- Rainer 2009, p. 145.

- Rainer, Janos. Imre Nagy: A Biography

- Richard Solash, "Hungary: U.S. President To Honour 1956 Uprising" Archived 9 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 20 June 2006

- The Counter-revolutionary Conspiracy of Imre Nagy and his Accomplices White Book, published by the Information Bureau of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People's Republic (No date).

- David Pryce-Jones, "What the Hungarians wrought: the meaning of October 1956", National Review, 23 October 2006

- Gunther, John (1961). Inside Europe Today. New York City: Harper & Brothers. p. 337. LCCN 61009706.

- Kamm, Henry (8 February 1989). "Budapest Journal; The Lasting Pain of '56: Can the Past Be Reburied?". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- 1798 Friedrich Schiller "Song of the Bell"

- Rainer 2009, p. 190.

- Kamm, Henry (17 June 1989). "Hungarian Who Led '56 Revolt Is Buried as a Hero". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Rainer 2009, p. 191.

- "Hungary removes uprising hero's statue". BBC. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "The Relocation of Imre Nagy's Statue Draws Controversy". HungaryToday. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- "Hungary removes statue of anti-Soviet icon Imre Nagy – DW – 29.12.2018". DW.COM. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Hungary's Orban under fire for removing statue". The Sun. Malaysia. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Rainer 2009, p. 87.

- "Erzsebet Nagy, only child of Hungary's 1956 revolution prime minister Imre Nagy, dies". PR-inside.com. Associated Press. 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

Bibliography

- Granville, Johanna (2004). The First Domino: International Decision Making During the Hungarian Crisis of 1956. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-298-0.

- Rainer, János M. (2009) [2002]. Imre Nagy: A Biography. Translated by Legters, Lyman H. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-959-1.

Further reading

- Gyula Háy (Julius Hay). Born 1900: memoirs. Hutchinson: 1974.

- Johanna Granville. "Imre Nagy aka 'Volodya' – A Dent in the Martyr's Halo?", "Cold War International History Project Bulletin", no. 5 (Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, Washington, D.C.), Spring, 1995, pp. 28, and 34–37.

- Johanna Granville, trans., "Soviet Archival Documents on the Hungarian Revolution, 24 October – 4 November 1956", Cold War International History Project Bulletin, no. 5 (Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, Washington, D.C.), Spring, 1995, pp. 22–23, 29–34.

- Johanna Granville, The First Domino: International Decision Making During the Hungarian Crisis of 1956", Texas A & M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- KGB Chief Vladimir Kryuchkov to CC CPSU, 16 June 1989 (trans. Johanna Granville). Cold War International History Project Bulletin 5 (1995): 36 [from: TsKhSD, F. 89, Per. 45, Dok. 82.]

- Alajos Dornbach, The Secret Trial of Imre Nagy, Greenwood Press, 1995. ISBN 0-275-94332-1

- Peter Unwin, Voice in the Wilderness: Imre Nagy and the Hungarian Revolution, Little, Brown, 1991. ISBN 0-356-20316-6

- Karl Benziger, Imre Nagy, Martyr of the Nation: Contested History, Legitimacy, and Popular Memory in Hungary. Lexington Books, 2008. ISBN 0-7391-2330-0