Indian Removal Act

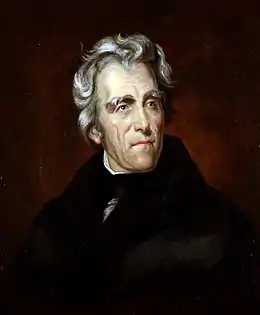

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law authorized the president to negotiate with southern (including Mid-Atlantic) Native American tribes for their removal to federal territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for white settlement of their ancestral lands.[lower-alpha 1][2][3] The Act was signed by Andrew Jackson and it was strongly enforced under his administration and that of his successor Martin Van Buren, which extended until 1841.[4]

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 21st United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 21–148 |

| Statutes at Large | 4 Stat. 411 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Military career

7th President of the United States

Presidency

First term

Second term

Post-presidency

Legacy

|

||

The Act was strongly supported by southern and northwestern populations, but was opposed by native tribes and the Whig Party. The Cherokee worked together to stop this relocation, but were unsuccessful; they were eventually forcibly removed by the United States government in a march to the west that later became known as the Trail of Tears, which has been described as an act of genocide, because many died during the removals.[5]

Background

Cultural assimilation

When Europeans and Native Americans came into contact during colonial times or in the early United States, the Europeans felt their civilization to be superior: they were Christians, and they believed their notions of private property to be a superior system of land tenure. European settlers adopted a practice of cultural assimilation, wherein Cherokee peoples were forced to adopt aspects of European civilization. This acculturation was originally proposed by George Washington and was well underway among the Cherokee and the Choctaw by the beginning of the 19th century.[6] Native peoples were encouraged to adopt European customs. First, they were forced to convert to Christianity and abandon traditional religious practices. They were also required to learn to speak and read English, although there was interest in creating a writing and printing system for a few Native languages, especially Cherokee, exemplified by Sequoyah’s Cherokee syllabary. The Native Americans also had to adopt settler values, such as monogamous heterosexual marriage and abandon non-marital sex. Finally, they had to accept the concept of individual ownership of land and other property (including, in some instances, African slaves). Many Cherokee people adopted all, or some, of these practices, including John Ross (Cherokee chief), John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, as represented by the newspaper he edited, The Cherokee Phoenix.[7]

The perceived failure of this policy

The United States government began a systematic effort to remove American Indian tribes from the Southeast.[8] The Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee-Creek, Seminole, and original Cherokee nations[lower-alpha 2] had been established as autonomous nations in the southeastern United States.

Andrew Jackson sought to renew a policy of political and military action for the removal of the Indians from these lands and worked toward enacting a law for Indian removal.[9][10][7][11][12] In his 1829 State of the Union address, Jackson called for Indian removal.[13]

The Indian Removal Act was put in place to give Native land to southern states, especially Georgia . The act was passed in 1830, although dialogue had been ongoing since 1802 between Georgia and the federal government concerning the possibility of such an act. Ethan Davis states that "the federal government had promised Georgia that it would extinguish Indian title within the state's borders by purchase 'as soon as such purchase could be made upon reasonable terms'".[14] As time passed, Southern states began to speed up the process by claiming that the deal between Georgia and the federal government was invalid and that Southern states could pass laws extinguishing Indian title themselves. In response, the federal government passed the Indian Removal Act on May 28, 1830, in which President Jackson agreed to divide the United States territory west of the Mississippi River into districts for tribes to replace the land from which they were removed.

In the 1823 case of Johnson v. M'Intosh, the United States Supreme Court handed down a decision stating that Indians could occupy and control lands within the United States but could not hold title to those lands.[15] Jackson viewed the union as a federation of highly esteemed states, as was common before the American Civil War. He opposed Washington's policy of establishing treaties with Indian tribes as if they were foreign nations. Thus, the creation of Indian jurisdictions was a violation of state sovereignty under Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution. As Jackson saw it, either Indians comprised sovereign states (which violated the Constitution) or they were subject to the laws of existing states of the Union. Jackson urged Indians to assimilate and obey state laws. Further, he believed that he could only accommodate the desire for Indian self-rule in federal territories, which required resettlement west of the Mississippi River on federal lands.[16][17]

Support and opposition

The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, especially in Georgia, which was the largest state in 1802 and was involved in a jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokee. President Jackson hoped that removal would resolve the Georgia crisis.[18] Besides the Five Civilized Tribes, additional people affected included the Wyandot, the Kickapoo, the Potowatomi, the Shawnee, and the Lenape.[19]

The Indian Removal Act was controversial. Many Americans during this time favored its passage, but there was also significant opposition. Many Christian missionaries protested against it, most notably missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts. In Congress, New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett spoke out against the legislation. The Removal Act passed only after a bitter debate in Congress.[20][21] Clay extensively campaigned against it on the National Republican Party ticket in the 1832 United States presidential election.[21]

Jackson viewed the demise of Indigenous nations as inevitable, pointing to the advancement of settled life and the demise of tribal nations in the American northeast. He called his Northern critics hypocrites, given the North's history regarding tribes within their territory. Jackson stated that "progress requires moving forward."[22]

Humanity has often wept over the fate of the aborigines of this country and philanthropy has long been busily employed in devising means to avert it, but its progress has never for a moment been arrested, and one by one have many powerful tribes disappeared from the earth... But true philanthropy reconciles the mind to these vicissitudes as it does to the extinction of one generation to make room for another... In the monuments and fortresses of an unknown people, spread over the extensive regions of the West, we behold the memorials of a once powerful race, which was exterminated or has disappeared to make room for the existing savage tribes… Philanthropy could not wish to see this continent restored to the condition in which it was found by our forefathers. What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?[23][24][25]

According to historian H. W. Brands, Jackson sincerely believed that his population transfer was a "wise and humane policy" that would save the Native Americans from "utter annihilation". Jackson portrayed the removal as a generous act of mercy.[26]

According to Robert M. Keeton, proponents of the bill used biblical narratives to justify the forced resettlement of Native Americans.[27]

Vote

On April 24, 1830, the Senate passed the Indian Removal Act by a vote of 28 to 19.[28] On May 26, 1830, the House of Representatives passed the Act by a vote of 101 to 97.[29] On May 28, 1830, the Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson.

Implementation

The Removal Act paved the way for the forced expulsion of tens of thousands of American Indians from their land into the West in an event widely known as the "Trail of Tears," a forced resettlement of the Indian population.[30][31][32][33] The first removal treaty signed was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which Choctaws in Mississippi ceded land east of the river in exchange for payment and land in the West. The Treaty of New Echota was signed in 1835 and resulted in the removal of the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears.

The Seminoles and other tribes did not leave peacefully, as they resisted the removal along with fugitive slaves. The Second Seminole War lasted from 1835 to 1842 and resulted in the government allowing them to remain in south Florida swampland. Only a small number remained, and around 3,000 were removed in the war.[34]

See also

Notes

- The U.S. Senate passed the bill on April 24, 1830 (28–19), the U.S. House passed it on May 26, 1830 (102–97).[1]

- These tribes were referred to as the "Five Civilized Tribes" by colonial settlers.

References

Citations

- Prucha, Francis Paul, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, Volume I, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984, p. 206.

- The Congressional Record; May 26, 1830; House vote No. 149; Government Tracker online; retrieved October 2015

- "Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents of Americas History". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- Lewey, Guenter (September 1, 2004). "Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?". Commentary. Retrieved March 8, 2017. Also available in reprint from the History News Network.

- The "Indian Problem". 10:51–11:17: National Museum of the American Indian. March 3, 2015. Event occurs at 12:21. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

When you move a people from one place to another, when you displace people, when you wrench people from their homelands ... wasn't that genocide? We don't make the case that there was genocide. We know there was. Yet here we are.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Thor, The Mighty (2003). "Chapter 2 "Both White and Red"". Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. The University of Georgia Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8203-2731-0.

- Perdue, Theda (2007). The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. Michael D. Green. New York. ISBN 978-0-670-03150-4. OCLC 74987776.

- "Indian Removal". PBS Africans in America: Judgment Day. WGBH Educational Foundation. 1999.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1803). "President Thomas Jefferson to William Henry Harrison, Governor of Indiana Territory". Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- Jackson, Andrew. "President Andrew Jackson's Case for the Removal Act". Mount Holyoke College. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston. ISBN 978-0-8070-0040-3. OCLC 868199534.

- Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (2019). As long as grass grows : the indigenous fight for environmental justice, from colonization to Standing Rock. Boston, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-8070-7378-4. OCLC 1044542033.

- "Andrew Jackson calls for Indian removal – North Carolina Digital History". www.learnnc.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-12. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- Davis, Ethan. "An Administrative Trail of Tears: Indian Removal". The American Journal of Legal History. 50 (1): 50–55.

- "Indial Removal 1814–1858". Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- Brands 2006, p. 488.

- Wilson, Woodrow (1898). Division and Reunion 1829–1889. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 35–38.

Indian question.

- "Indian Removal Act". A&E Television Networks. 2011. Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "Timeline of Removal". Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. (2007) ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7 p. 348–52.

- Farris, Scott (2012). Almost president : the men who lost the race but changed the nation. Internet Archive. Guilford, CN: Lyons Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7627-6378-8.

- Brands 2006, p. 489-498.

- Brands 2006, p. 490.

- "Statements from the Debate on Indian Removal". Columbia University. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- Steven Mintz, ed. (1995). Native American Voices: A History and Anthology. Vol. 2. Brandywine Press. pp. 115–16.

- Brands 2006, p. 489-493.

- Keeton, Robert M. (2015-07-10). 5. "The Race of Pale Men Should Increase and Multiply". New York University Press. pp. 125–149. doi:10.18574/nyu/9781479876778.003.0006. ISBN 978-1-4798-9573-1.

- "To Order Engrossment and Third Reading of S. 102". GovTrack. 2013-07-07. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- "To Pass S. 102. (P. 729)". GovTrack. 2013-07-07. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

The bill passed 101–97, with 11 not voting

- Greenwood, Robert E. (2007). Outsourcing Culture: How American Culture has Changed From "We the People" Into a One World Government. Outskirts Press. p. 97.

- Molhotra, Rajiv (2009). "American Exceptionalism and the Myth of the American Frontiers". In Rajani Kannepalli Kanth (ed.). The Challenge of Eurocentrism. Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 180, 184, 189, 199. ISBN 9780230612273.

- Finkelman, Paul; Kennon, Donald R. (2008). Congress and the Emergence of Sectionalism. Ohio University Press. pp. 15, 141, 254.

- BKiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. pp. 328, 330.

- Foner, Eric (2006). Give me liberty. Norton. ISBN 9780393927825.

Cited works

- Brands, H.W. (2006). Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times. Anchor. ISBN 978-1-4000-3072-9.

External links

- Indian Removal Act and related resources, at the Library of Congress

- 1830 State of the Union on Indian Removal; Text at 100 Milestone Documents