Genetic history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The genetic history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas (also named Amerindians or Amerinds by physical anthropologists) is divided into two distinct episodes: the initial peopling of the Americas during about 20,000 to 14,000 years ago (20–14 kya), and European contact, after about 500 years ago.[1][2] The former is the determinant factor for the number of genetic lineages, zygosity mutations and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous Amerindian populations.[3]

Most Amerindian groups are derived from two ancestral lineages, which formed in Siberia prior to the Last Glacial Maximum, between about 36,000 and 25,000 years ago, East Eurasian and Ancient North Eurasian. They later dispersed throughout the Americas after about 16,000 years ago (exceptions being the Na Dene and Eskimo–Aleut speaking groups, which are derived partially from Siberian populations which entered the Americas at a later time).[4]

During the early 2000s, archaeogenetics was primarily based on human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups and human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups.[5] Autosomal "atDNA" markers are also used, but differ from mtDNA or Y-DNA in that they overlap significantly.[6]

Analyses of genetics among Amerindian and Siberian populations have been used to argue for early isolation of founding populations on Beringia[7] and for later, more rapid migration from Siberia through Beringia into the New World.[8] The microsatellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial peopling of the region.[9] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit Haplogroup Q-M242; however, they are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA and atDNA mutations.[10][11][12] This suggests that the peoples who first settled in the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations than those who penetrated farther south in the Americas.[13][14] Linguists and biologists have reached a similar conclusion based on analysis of Amerindian language groups and ABO blood group system distributions.[15][16][17][18]

Autosomal DNA

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American landmass is also measured using autosomal (atDNA) micro-satellite markers genotyped; sampled from North, Central, and South America and analyzed against similar data available from other indigenous populations worldwide.[19][20] The Amerindian populations show a lesser genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions.[20] Observed is a decreasing genetic diversity as geographic distance from the Bering Strait occurs, as well as a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (the genetic entry point).[19][20] Also observed is evidence of a greater level of diversity and lesser level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America.[19][20] There is a relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations, a scenario that implies that coastal routes (in this case along the coast of the Pacific Ocean) were easier for migrating peoples (more genetic contributors) to traverse in comparison with inland routes.[19]

The over-all pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70), which grew by many orders of magnitude over 800 – 1000 years.[21][22] The data also shows that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic, and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas.[22][23]

According to an autosomal genetic study from 2012,[24] Native Americans descend from at least three main migrant waves from East Asia. Most of it is traced back to a single ancestral population, called 'First Americans'. However, those who speak Inuit languages from the Arctic inherited almost half of their ancestry from a second East Asian migrant wave. And those who speak Na-dene, on the other hand, inherited a tenth of their ancestry from a third migrant wave. The initial settling of the Americas was followed by a rapid expansion southwards along the west coast, with little gene flow later, especially in South America. One exception to this are the Chibcha speakers of Colombia, whose ancestry comes from both North and South America.[24]

In 2014, the autosomal DNA of a 12,500+-year-old infant from Montana was sequenced.[25] The DNA was taken from a skeleton referred to as Anzick-1, found in close association with several Clovis artifacts. Comparisons showed strong affinities with DNA from Siberian sites, and virtually ruled out that particular individual had any close affinity with European sources (the "Solutrean hypothesis"). The DNA also showed strong affinities with all existing Amerindian populations, which indicated that all of them derive from an ancient population that lived in or near Siberia.[26]

Linguistic studies have reinforced genetic studies, with ancient patterns having been found between the languages spoken in Siberia and those spoken in the Americas.[27]

Two 2015 autosomal DNA genetic studies confirmed the Siberian origins of the Natives of the Americas. However an ancient signal of shared ancestry with Australasians (Natives of Australia, Melanesia and the Andaman Islands) was detected among the Natives of the Amazon region. The migration coming out of Siberia would have happened 23,000 years ago.[28][29][30]

A 2018 study analysed 11,500BC old indigenous samples. The genetic evidence suggests that all Native Americans ultimately descended from a single founding population that initially split from a Basal-East Asian source population in Mainland Southeast Asia around 36,000 years ago, the same time at which the proper Jōmon people divided from Basal-East Asians, either together with Ancestral Native Americans or during a separate expansion wave. The authors also provided evidence that the basal northern and southern Native American branches, to which all other Indigenous peoples belong, diverged around 16,000 years ago.[4][31] An indigenous American sample from 16,000BC in Idaho, which is craniometrically similar to modern Native Americans as well as Paleosiberias, was found to have been largely East-Eurasian genetically, and showed high affinity with contemporary East Asians, as well as Jōmon period samples of Japan, confirming that Ancestral Native Americans split from an East-Eurasian source population somewhere in eastern Siberia.[32]

A study published in the Nature journal in 2018 concluded that Native Americans descended from a single founding population which initially divided from East Asians about ~36,000 BC, with geneflow between Ancestral Native Americans and Siberians persisting until ~25,000BC, before becoming isolated in the Americas at ~22,000BC. Northern and Southern American Native subpopulationes split from each other at ~17,500BC. There is also some evidence for a back-migration from the Americas into Siberia after ~11,500BC.[4]

A study published in the Cell journal in 2019, analysed 49 ancient Native American samples from all over North and South America, and concluded that all Native American populations descended from a single ancestral source population which divided from Siberians and East Asians, and gave rise to the Ancestral Native Americans, which later diverged into the various indigenous groups. The authors further dismissed previous claims for the possibility of two distinct population groups among the peopling of the Americas. Both, Northern and Southern Native Americans are closest to each other, and do not show evidence of admixture with hypothetical previous populations.[33]

A review article published in the Nature journal in 2021, which summarized the results of previous genomic studies, similarly concluded that all Native Americans descended from the movement of people from Northeast Asia into the Americas. These Ancestral Americans, once south of the continental ice sheets, spread and expanded rapidly, and branched into multiple groups, which later gave rise to the major subgroups of Native American populations. The study also dismissed the existence of an hypothetical distinct non-Native American population (suggested to have been related to Indigenous Australians and Papuans), sometimes called "Paleoamerican". The authors explained that these previous claims were based on a misinterpreted genetic echo, which was revealed to represent early East-Eurasian geneflow (close but distinct to the 40,000BC old Tianyuan lineage) into Aboriginal Australians and Papuans.[34][35]

Paternal lineages

A "Central Siberian" origin has been postulated for the paternal lineage of the source populations of the original migration into the Americas.[36]

Membership in haplogroups Q and C3b implies indigenous American patrilineal descent.[37]

The micro-satellite diversity and distribution of a Y lineage specific to South America suggest that certain Amerindian populations became isolated after the initial colonization of their regions.[38] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, but are distinct from other indigenous Amerindians with various mtDNA and autosomal DNA (atDNA) mutations.[10][39][40] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.[41][42]

Haplogroup Q

.png.webp)

Q-M242 (mutational name) is the defining (SNP) of Haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) (phylogenetic name).[44][45] In Eurasia, haplogroup Q is found among indigenous Siberian populations, such as the modern Chukchi and Koryak peoples, as well as some Southeast Asians, such as the Dayak people. In particular, two groups exhibit large concentrations of the Q-M242 mutation, the Ket (93.8%) and the Selkup (66.4%) peoples.[46] The Ket are thought to be the only survivors of ancient wanderers living in Siberia.[47] Their population size is very small; there are fewer than 1,500 Ket in Russia.2002[21] The Selkup have a slightly larger population size than the Ket, with approximately 4,250 individuals.[48]

Starting the Paleo-Indians period, a migration to the Americas across the Bering Strait (Beringia) by a small population carrying the Q-M242 mutation occurred.[11] A member of this initial population underwent a mutation, which defines its descendant population, known by the Q-M3 (SNP) mutation.[49] These descendants migrated all over the Americas.[44]

Haplogroup Q-M3 is defined by the presence of the rs3894 (M3) (SNP).[1][21][50] The Q-M3 mutation is roughly 15,000 years old as that is when the initial migration of Paleo-Indians into the Americas occurred.[51][52] Q-M3 is the predominant haplotype in the Americas, at a rate of 83% in South American populations,[9] 50% in the Na-Dené populations, and in North American Eskimo-Aleut populations at about 46%.[46] With minimal back-migration of Q-M3 in Eurasia, the mutation likely evolved in east-Beringia, or more specifically the Seward Peninsula or western Alaskan interior. The Beringia land mass began submerging, cutting off land routes.[46][53][19]

Since the discovery of Q-M3, several subclades of M3-bearing populations have been discovered. An example is in South America, where some populations have a high prevalence of (SNP) M19, which defines subclade Q-M19.[9] M19 has been detected in (59%) of Amazonian Ticuna men and in (10%) of Wayuu men.[9] Subclade M19 appears to be unique to South American Indigenous peoples, arising 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.[9] This suggests that population isolation, and perhaps even the establishment of tribal groups, began soon after migration into the South American areas.[21][54] Other American subclades include Q-L54, Q-Z780, Q-MEH2, Q-SA01, and Q-M346 lineages. In Canada, two other lineages have been found. These are Q-P89.1 and Q-NWT01.

Haplogroup R1

Haplogroup R1 (Y-DNA) is the second most predominant Y haplotype found among indigenous Amerindians after Q (Y-DNA).[55] The distribution of R1 is believed by some to be associated with the re-settlement of Eurasia after the last glacial maximum. One theory that was introduced during European colonization.[55] R1 is very common throughout all of Eurasia except East Asia and Southeast Asia. R1 (M173) is found predominantly in North American groups like the Ojibwe (50-79%), Seminole (50%), Sioux (50%), Cherokee (47%), Dogrib (40%) and Tohono O'odham (Papago) (38%).[55]

Raghavan et al. 2014 found that autosomal evidence indicates that skeletal remains of a south-central Siberian child carrying R* y-dna (Mal'ta boy-1) "is basal to modern-day western Eurasians and genetically closely related to modern-day Amerindians, with no close affinity to east Asians. This suggests that populations related to contemporary western Eurasians had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought." Sequencing of another south-central Siberian (Afontova Gora-2) revealed that "western Eurasian genetic signatures in modern-day Amerindians derive not only from post-Columbian admixture, as commonly thought, but also from a mixed ancestry of the First Americans."[56] It is further theorized if "Mal'ta might be a missing link, a representative of the Asian population that admixed both into Europeans and Native Americans."[57]

On FTDNA public tree, out of 626 US indigenous Americans K-YSC0000186, all are Q, R1b-M269, R1a-M198, R2-M479 and 2 most likely not tested further than R1b-M343 .[58]

Haplogroup C-P39

.PNG.webp)

Haplogroup C-M217 is found mainly in indigenous Siberians, Mongolians, and Kazakhs. Haplogroup C-M217 is the most widespread and frequently occurring branch of the greater (Y-DNA) haplogroup C-M130. Haplogroup C-M217 descendant C-P39 is most commonly found in today's Na-Dené speakers, with the greatest frequency found among the Athabaskans at 42%, and at lesser frequencies in some other Native American groups.[11] This distinct and isolated branch C-P39 includes almost all the Haplogroup C-M217 Y-chromosomes found among all indigenous peoples of the Americas.[60]

Some researchers feel that this may indicate that the Na-Dené migration occurred from the Russian Far East after the initial Paleo-Indian colonization, but prior to modern Inuit, Inupiat and Yupik expansions.[11][10][61]

In addition to in Na-Dené peoples, haplogroup C-P39 (C2b1a1a) is also found among other Native Americans such as Algonquian- and Siouan-speaking populations.[62][63] C-M217 is found among the Wayuu people of Colombia and Venezuela.[62][63]

Data

Listed here are notable indigenous peoples of the Americas by human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups based on relevant studies. The samples are taken from individuals identified with the ethnic and linguistic designations in the first two columns, the fourth column (n) is the sample size studied, and the other columns give the percentage of the particular haplogroup.

| Group | Language | Place | n | C | Q | R1 | Others | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algonquian[nb 1] | Algic | Northeast North America | 155 | 7.7 | 33.5 [nb 2] | 38.1 | 20.6 | Bolnick 2006[64] |

| Apache | Na-Dené | SW United States | 96 | 14.6 | 78.1 | 5.2 | 2.1 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| Athabaskan[nb 3] | Na-Dené | Western North America | 243 | 11.5 | 70.4 | 18.1 | Malhi 2008[65] | |

| Cherokee | Iroquoian | SE United States | 62 | 1.6 | 50.0 [nb 4] | 37.1 | 11.3 | Bolnick 2006[64] |

| Cherokee | Iroquoian | Eastern North America | 30 | 50.0 | 46.7 | 3.3 | Malhi 2008[65] | |

| Cheyenne | Algic | United States | 44 | 16 | 61 | 16 | 7 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| Chibchan[nb 5] | Macro-Chibchan | Panama | 26 | 100 | Zegura 2004[11] | |||

| Chipewyan | Na-Dené | Canada | 48 | 6 | 31 [nb 6] | 62.5[nb 7] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |

| Chippewa | Algic | Eastern North America | 97 | 4.1 | 15.9 [nb 8] | 50.5 | 29.9 | Bolnick 2006[64] |

| Dogrib | Na-Dené | Canada | 15 | 33 | 27 | 40 | Malhi 2008[65] | |

| Dogrib | Na-Dené | Canada | 37 | 35.1 | 45.9 [nb 9] | 8.1 | 10.8 | Dulik 2012[66] |

|

Gê[nb 10] |

Macro-Jê | Brazil | 51 | 92 [nb 11] | 8 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | ||

| Guaraní | Tupian | Paraguay | 59 | 86 [nb 12] | 9 | 5 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |

| Inga | Quechua | Colombia | 11 | 78 [nb 13] | 11 | 11 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |

| Inuit | Eskimo–Aleut | North American Arctic | 60 | 80.0 | 11.7 | 8.3 | Zegura 2004[11] | |

| Inuvialuit | Eskimo–Aleut | Canada | 56 | 1.8 | 55.1 [nb 14] | 33.9 | 8.9 | Dulik 2012[66] |

| Mayan | Mesoamerica | 71 | 87.3 | 12.7 | Zegura 2004[11] | |||

| Mixe | Mixe–Zoque | Mexico | 12 | 100 | Zegura 2004[11] | |||

| Mixtec | Oto-Manguean | Mexico | 28 | 93 | 7 | Zegura 2004[11] | ||

| Muskogean[nb 15] | Muskogean | SE United States | 36 | 2.8 | 75 [nb 16] | 11.1 | 11.1 | Bolnick 2006[64] |

| Nahua | Uto-Aztecan | Mexico | 17 | 94 | 6 | Malhi 2008[65] | ||

| Native Americans (United States) |

United States | 398 | 9.0 | 58.1 | 22.2 | 10.7 | Hammer 2005[67] | |

| Navajo | Na-Dené | SW United States | 78 | 1.3 | 92.3 | 2.6 | 3.8 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| Native North Americans | North America | 530 | 6.0 | 77.2 | 12.5 | 4.3 | Zegura 2004[11] | |

| Papago | Uto-Aztecan | SW United States | 13 | 61.5 | 38.5 | Malhi 2008[65] | ||

| Seminole | Muskogean | Eastern North America | 20 | 45.0 | 50.0 | 5.0 | Malhi 2008[65] | |

| Sioux | Macro-Siouan | Central North America | 44 | 11 | 25 | 50 | 14 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| South America | Amerindian | South America | 390 | 92 [nb 17] | 4 | 4 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |

| Tanana | Na-Dené | Northwest North America | 12 | 42 | 42 | 8 | 8 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| Ticuna | Ticuna–Yuri | West Amazon basin | 33 | 100 [nb 18] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |||

| Tlingit | Na-Dené | Pacific Northwest | 11 | 18 [nb 19] | 82 [nb 20] | Dulik 2012[66] | ||

| Tupí–Guaraní[nb 21] | Tupian | Brazil | 54 | 100 [nb 22] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |||

| Uto-Aztecan[nb 23] | Uto-Aztecan | Mexico, Arizona | 167 | 93.4 | 6.0 | Malhi 2008[65] | ||

| Warao | Warao (isolate) | Caribbean South America | 12 | 100 [nb 24] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |||

| Wayúu | Arawakan | Guajira Peninsula | 19 | 69 [nb 25] | 21 | 10 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |

| Wayúu | Arawakan | Guajira Peninsula | 25 | 8 | 36 | 44 | 12 | Zegura 2004[11] |

| Yagua | Peba–Yaguan | Peru | 7 | 100 [nb 26] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |||

| Yukpa | Cariban | Colombia | 12 | 100 [nb 27] | Bortoloni 2003[9] | |||

| Zapotec | Oto-Manguean | Mexico | 16 | 75 | 6 | 19 | Zegura 2004[11] | |

| Zenú | extinct | Colombia | 30 | 81 [nb 28] | 19 | Bortoloni 2003[9] | ||

Maternal lineages

The common occurrence of the mtDNA Haplogroups A, B, C, and D among eastern Asian and Amerindian populations has long been recognized, along with the presence of Haplogroup X.[68] As a whole, the greatest frequency of the four Amerindian associated haplogroups occurs in the Altai-Baikal region of southern Siberia.[69] Some subclades of C and D closer to the Amerindian subclades occur among Mongolian, Amur, Japanese, Korean, and Ainu populations.[68][70]

.PNG.webp)

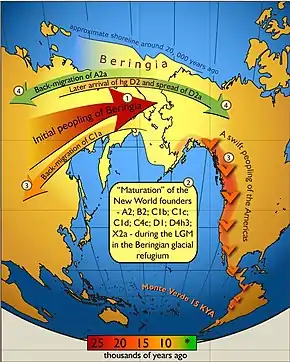

When studying human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups, the results indicated that Indigenous Amerindian haplogroups, including haplogroup X, are part of a single founding East Asian population. It also indicates that the distribution of mtDNA haplogroups and the levels of sequence divergence among linguistically similar groups were the result of multiple preceding migrations from Bering Straits populations.[71][72] All indigenous Amerindian mtDNA can be traced back to five haplogroups, A, B, C, D and X.[73][74] More specifically, indigenous Amerindian mtDNA belongs to sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1b, C1c, C1d, D1, and X2a (with minor groups C4c, D2a, and D4h3a).[7][72] This suggests that 95% of Indigenous Amerindian mtDNA is descended from a minimal genetic founding female population, comprising sub-haplogroups A2, B2, C1b, C1c, C1d, and D1.[73] The remaining 5% is composed of the X2a, D2a, C4c, and D4h3a sub-haplogroups.[72][73]

X is one of the five mtDNA haplogroups found in Indigenous Amerindian peoples. Unlike the four main American mtDNA haplogroups (A, B, C and D), X is not at all strongly associated with east Asia.[21] Haplogroup X genetic sequences diverged about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago to give two sub-groups, X1 and X2. X2's subclade X2a occurs only at a frequency of about 3% for the total current indigenous population of the Americas.[21] However, X2a is a major mtDNA subclade in North America; among the Algonquian peoples, it comprises up to 25% of mtDNA types.[1][75] It is also present in lower percentages to the west and south of this area — among the Sioux (15%), the Nuu-chah-nulth (11%–13%), the Navajo (7%), and the Yakama (5%).[76] Haplogroup X is more strongly present in the Near East, the Caucasus, and Mediterranean Europe.[76] The predominant theory for sub-haplogroup X2a's appearance in North America is migration along with A, B, C, and D mtDNA groups, from a source in the Altai Mountains of central Asia.[77][78][79][80] Haplotype X6 was present in the Tarahumara 1.8% (1/53) and Huichol 20% (3/15)[81]

Sequencing of the mitochondrial genome from Paleo-Eskimo remains (3,500 years old) are distinct from modern Amerindians, falling within sub-haplogroup D2a1, a group observed among today's Aleutian Islanders, the Aleut and Siberian Yupik populations.[82] This suggests that the colonizers of the far north, and subsequently Greenland, originated from later coastal populations.[82] Then a genetic exchange in the northern extremes introduced by the Thule people (proto-Inuit) approximately 800–1,000 years ago began.[40][83] These final Pre-Columbian migrants introduced haplogroups A2a and A2b to the existing Paleo-Eskimo populations of Canada and Greenland, culminating in the modern Inuit.[40][83]

A 2013 study in Nature reported that DNA found in the 24,000-year-old remains of a young boy from the archaeological Mal'ta-Buret' culture suggest that up to one-third of indigenous Americans' ancestry can be traced back to western Eurasians, who may have "had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought"[56] "We estimate that 14 to 38 percent of Amerindian ancestry may originate through gene flow from this ancient population," the authors wrote. Professor Kelly Graf said,

"Our findings are significant at two levels. First, it shows that Upper Paleolithic Siberians came from a cosmopolitan population of early modern humans that spread out of Africa to Europe and Central and South Asia. Second, Paleoindian skeletons like Buhl Woman with phenotypic traits atypical of modern-day indigenous Americans can be explained as having a direct historical connection to Upper Paleolithic Siberia."[56]

A route through Beringia is seen as more likely than the Solutrean hypothesis.[56] An abstract in a 2012 issue of the "American Journal of Physical Anthropology" states that "The similarities in ages and geographical distributions for C4c and the previously analyzed X2a lineage provide support to the scenario of a dual origin for Paleo-Indians. Taking into account that C4c is deeply rooted in the Asian portion of the mtDNA phylogeny and is indubitably of Asian origin, the finding that C4c and X2a are characterized by parallel genetic histories definitively dismisses the controversial hypothesis of an Atlantic glacial entry route into North America."[84]

Another study, also focused on the mtDNA (that which is inherited through only the maternal line),[7] revealed that the indigenous people of the Americas have their maternal ancestry traced back to a few founding lineages from East Asia, which would have arrived via the Bering strait. According to this study, it is probable that the ancestors of the Native Americans would have remained for a time in the region of the Bering Strait, after which there would have been a rapid movement of settling of the Americas, taking the founding lineages to South America.

According to a 2016 study, focused on mtDNA lineages, "a small population entered the Americas via a coastal route around 16.0 ka, following previous isolation in eastern Beringia for ~2.4 to 9 thousand years after separation from eastern Siberian populations. Following a rapid movement throughout the Americas, limited gene flow in South America resulted in a marked phylogeographic structure of populations, which persisted through time. All of the ancient mitochondrial lineages detected in this study were absent from modern data sets, suggesting a high extinction rate. To investigate this further, we applied a novel principal components multiple logistic regression test to Bayesian serial coalescent simulations. The analysis supported a scenario in which European colonization caused a substantial loss of pre-Columbian lineages".[85]

Genetic admixture

Ancient Beringians

Recent archaeological findings in Alaska have shed light on the existence of a previously unknown Native American population that has been academically named "Ancient Beringians."[86] Although it is popularly agreed among archeologists that early settlers had crossed into Alaska from Russia through the Bering Strait land bridge, the issue of whether or not there was one founding group or several waves of migration is a controversial and prevalent debate among academics in the field today. In 2018, the sequenced DNA of a native girl, whose remains were found at the Sun River archaeological site in Alaska in 2013, proved not to match the two recognized branches of Native Americans and instead belonged to the early population of Ancient Beringians.[87] This breakthrough is said to be the first direct genomic evidence that there was potentially only one wave of migration in the Americas that occurred, with genetic branching and division transpiring after the fact. The migration wave is estimated to have emerged about 20,000 years ago.[86] The Ancient Beringians are said to be a common ancestral group among contemporary Native American populations today, which differs in results collected from previous research that suggests that modern populations are descendants of either Northern and Southern branches.[86] Experts were also able to use wider genetic evidence to establish that the split between the Northern and Southern American branches of civilization from the Ancient Beringians in Alaska only occurred about 17,000 and 14,000 years,[24] further challenging the concept of multiple migration waves occurring during the very first stages of settlement.

Genetic evidence for "Paleoamerinds" consists of the presence of apparent admixture of archaic Sundadont lineages to the remote populations in the South American rain forest, and in the genetics of Patagonians-Fuegians.[88][89]

Nomatto et al. (2009) proposed migration into Beringia occurred between 40k and 30k cal years BP, with a pre-LGM migration into the Americas followed by isolation of the northern population following closure of the ice-free corridor.[90]

A 2016 genetic study of native peoples of the Amazonian region of Brazil (by Skoglund and Reich) showed evidence of admixture from a separate lineage of an otherwise unknown ancient people. This ancient group appears to be related to modern day "Australasian" peoples (i.e. Aboriginal Australians and Melanesians). This "Ghost population" was found in speakers of Tupian languages. They provisionally named this ancient group; "Population Y", after Ypykuéra, "which means 'ancestor' in the Tupi language family".[30] A 2021 genetic study dismissed the existence of an hypothetical Australasian component among Native Americans. The signal of the hypothetical Australasian component, can also be reproduced using the Basal-East Asian Tianyuan man sample, and thus does not represent "real Australasian affinity". The authors explained that the previous claims of possibly Australasian ancestry were based on a misinterpreted genetic echo, which was revealed to represent early East-Eurasian geneflow (represented by the 40,000BC old Tianyuan sample) into Aboriginal Australians and Papuans, which was lost in modern East Asians.[91][92]

Archaeological evidence for pre-LGM human presence in the Americas was first presented in the 1970s.[93][94] notably the "Luzia Woman" skull found in Brazil.[95][96][97]

Old world

Substantial racial admixture has taken place during and since the European colonization of the Americas.[98][99]

South and Central America

In Latin America in particular, significant racial admixture took place between the indigenous Amerind population, the European-descended colonial population, and the Sub-Saharan African populations imported as slaves. From about 1700, a Latin American terminology developed to refer to the various combinations of mixed racial descent produced by this.[100]

Many individuals who self-identify as one race exhibit genetic evidence of a multiracial ancestry.[101] The European conquest of South and Central America, beginning in the late 15th century, was initially executed by male soldiers and sailors from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal).[102] The new soldier-settlers fathered children with Amerindian women and later with African slaves.[103] These mixed-race children were generally identified by the Spanish colonist and Portuguese colonist as "Castas".[104]

North America

The North American fur trade during the 16th century brought many more European men, from France, Ireland, and Great Britain, who took North Amerindian women as wives.[105] Their children became known as "Métis" or "Bois-Brûlés" by the French colonists and "mixed-bloods", "half-breeds" or "country-born" by the English colonists and Scottish colonists.[106]

Native Americans in the United States are more likely than any other racial group to practice racial exogamy, resulting in an ever-declining proportion of indigenous ancestry among those who claim a Native American identity.[107] In the United States 2010 census, nearly 3 million people indicated that their race was Native American (including Alaska Native).[108] This is based on self-identification, and there are no formal defining criteria for this designation. Especially numerous was the self-identification of Cherokee ethnic origin,[109] a phenomenon dubbed the "Cherokee Syndrome", where some Americans believe they have a "long-lost Cherokee ancestor" without being able to identify that person in their family tree.[110][111] The context is the cultivation of an opportunistic ethnic identity related to the perceived prestige associated with Native American ancestry.[112] Native American identity in the Eastern United States is mostly detached from genetic descent, and especially embraced by people of predominantly European ancestry.[112][113] Some tribes have adopted criteria of racial preservation, usually through a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood, and practice disenrollment of tribal members unable to provide proof of Native American ancestry. This topic has become a contentious issue in Native American reservation politics.[114]

European diseases and genetic modification

A team led by Ripan Malhi, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana, conducted a study where they used a scientific technique known as whole exome sequencing to test immune-related gene variants within Native Americans.[115] Through analyzing ancient and modern native DNA, it was found that HLA-DQA1, a variant gene that codes for protein in charge of differentiating between healthy cells from invading viruses and bacteria were present in nearly 100% of ancient remains but only 36% in modern Native Americans.[115] These finding suggest that European-borne epidemics such as smallpox altered the disease landscape of the Americas, leaving survivors of these outbreaks less likely to carry variants like HLA-DQA1. This made them less able to cope with new diseases. The change in genetic makeup is measured by scientists to have occurred around 175 years ago, during a time when the smallpox epidemic was ranging through the Americas.

Blood groups

Prior to the 1952 confirmation of DNA as the hereditary material by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase, scientists used blood proteins to study human genetic variation.[116][117] The ABO blood group system is widely credited to have been discovered by the Austrian Karl Landsteiner, who found three different blood types in 1900.[118] Blood groups are inherited from both parents. The ABO blood type is controlled by a single gene (the ABO gene) with three alleles: i, IA, and IB.[119]

Research by Ludwik and Hanka Herschfeld during World War I found that the frequencies of blood groups A, B and O differed greatly from region to region.[117] The "O" blood type (usually resulting from the absence of both A and B alleles) is very common around the world, with a rate of 63% in all human populations.[120] Type "O" is the primary blood type among the indigenous populations of the Americas, in-particular within Central and South America populations, with a frequency of nearly 100%.[120] In indigenous North American populations the frequency of type "A" ranges from 16% to 82%.[120] This suggests again that the initial Amerindians evolved from an isolated population with a minimal number of individuals.[121][122]

The standard explanation for such a high population of Native Americans with blood type O comes from the idea of Genetic drift, in which the small nature of Native American populations meant the almost complete absence of any other blood gene being passed down through generations.[123] Other related explanations include the Bottleneck explanation which states that there were high frequencies of blood type A and B among Native Americans but severe population decline during the 1500s and 1600s caused by the introduction of disease from Europe resulted in the massive death toll of those with blood types A and B. Coincidentally, a large amount of the survivors were type O.[123]

| PEOPLE GROUP | O (%) | A (%) | B (%) | AB (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackfoot Confederacy (N. American Indian) | 17 | 82 | 0 | 1 |

| Bororo (Brazil) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eskimos (Alaska) | 38 | 44 | 13 | 5 |

| Inuit (Eastern Canada & Greenland) | 54 | 36 | 23 | 8 |

| Hawaiians (Polynesians, non-Amerindian) | 37 | 61 | 2 | 1 |

| Indigenous North Americans (as a whole Native Nations/First Nations) | 79 | 16 | 4 | 1 |

| Maya (modern) | 98 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Navajo | 73 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Peru | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The Dia antigen of the Diego antigen system has been found only in indigenous peoples of the Americas and East Asians, and in people with some ancestry from those groups. The frequency of the Dia antigen in various groups of indigenous peoples of the Americas ranges from almost 50% to 0%.[125] Differences in the frequency of the antigen in populations of indigenous people in the Americas correlate with major language families, modified by environmental conditions.[126]

See also

- Introduction to genetics

- Archaeogenetics

- Archaeology of the Americas

- Ancient DNA

- Clovis culture

- Early human migrations

- Genetic history of Africa

- Genetic history of Europe

- Genetic history of Italy

- Genetic history of North Africa

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula

- Genetic history of the Middle East

- Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia

- List of haplogroups of historic people

- Race and genetics

- Settlement of the Americas#Genomic age estimates

- List of Y-chromosome haplogroups in populations of the world

Notes

- Algonquian ethnic groups: Ojibwe, Cheyenne/Arapaho, Shawnee, Mi'kmaq, Kickapoo and Meskwaki.

- Q-M3=12.9; Q(xM3)=20.6.

- Athabaskan ethnic groups: Chipewyan, Tłı̨chǫ, Tanana, Apache and Navajo.

- Q-M3=32.; Q3(xM3)=17.7.

- Chibchan ethnic groups: Ngöbe and Kuna peoples.

- Q-M3=6; Q(xM3)=25.

- P1(xQ) 62.5%. While other studies identify this as R(xR2)/R1b,

the subject remains controversial (see Hammer, Michael F. et al 2005) - Q-M3=8.2; Q(xQ-M3)=7.2.

- Q-M3=40.5; Q(xM3)=5.4.

- Gê ethnic groups: Gorotire, Kaigang, Kraho, Mekranoti and Xikrin.

- Q-M3=90; Q(xM3)=2)

- Q-M3=79; Q(xM3)=7.

- Q-M3=11; Q(xM3)=67.

- Q-M3=10.7; NWT01=44.6.

- Muskogean ethnic groups: Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole.

- Q-M3=50.0; Q(xM3)=25.0.

- Q-M3=83; Q(xM3)=9.

- Q-M3=89; Q(xM3)=11.

- C3*=9; C3b=9

- Q-M3=64; Q-MEH2*=9; Q-NWT01=9.

- Tupi–Guarani Brazilian ethnic groups: Asuriní, Parakanã, Ka'apor and Wayampi.

- All examples of haplogroup Q were Q-M3.

- Uto-Aztecan ethnic groups: Pima, Tohono O'odham, Tarahumara, Nahua, Cora and Huichol.

- Q=M3

- Q-M3=48; Q(xM3)=21.

- Q-M3=86<; Q(xM3)=14.

- Q=M3

- Q-M3=33; Q(xM3)=48.

References

- Wendy Tymchuk (2008). "Learn about Y-DNA Haplogroup Q. Genebase Tutorials". Genebase Systems. Archived from the original on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- Orgel, Leslie E. (2004). "Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 39 (2): 99–123. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.537.7679. doi:10.1080/10409230490460765. PMID 15217990.

- Tallbear, Kim (2014). "The Emergence, Politics, and Marketplace of Native American DNA". In Kleinman, Daniel Lee; Moore, Kelly (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Science, Technology, and Society. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-136-23716-4. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Potter, Ben A.; Vinner, Lasse; et al. (January 2018). "Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans" (PDF). Nature. 553 (7687): 203–207. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..203M. doi:10.1038/nature25173. PMID 29323294. S2CID 4454580.

- Y Chromosome Consortium (2002). "A Nomenclature System for the Tree of Human Y-Chromosomal Binary Haplogroups". Genome Research. 12 (2): 339–348. doi:10.1101/gr.217602. PMC 155271. PMID 11827954.(Detailed hierarchical chart) Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Griffiths, Anthony J. F.; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; et al., eds. (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3771-1. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- Tamm, Erika; Kivisild, Toomas; Reidla, Maere; et al. (5 September 2007). "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLOS ONE. 2 (9): e829. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..829T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. PMC 1952074. PMID 17786201.

- Derenko, Miroslava; Malyarchuk, Boris; Grzybowski, Tomasz; et al. (21 December 2010). "Origin and Post-Glacial Dispersal of Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups C and D in Northern Asia". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15214. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515214D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015214. PMC 3006427. PMID 21203537.

- Bortolini, Maria-Catira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Thomas, Mark G.; et al. (September 2003). "Y-chromosome evidence for differing ancient demographic histories in the Americas". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (3): 524–539. doi:10.1086/377588. PMC 1180678. PMID 12900798.

- Ruhlen, Merritt (November 1998). "The Origin of the Na-Dene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (23): 13994–13996. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513994R. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13994. PMC 25007. PMID 9811914.

- Zegura, Stephen L.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; et al. (January 2004). "High-Resolution SNPs and Microsatellite Haplotypes Point to a Single, Recent Entry of Native American Y Chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (1): 164–175. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- Saillard, Juliette; Forster, Peter; Lynnerup, Niels; et al. (2000). "mtDNA Variation among Greenland Eskimos. The Edge of the Beringian Expansion". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (3): 718–726. doi:10.1086/303038. PMC 1287530. PMID 10924403.

- Schurr, Theodore G. (21 October 2004). "The Peopling of the New World: Perspectives from Molecular Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 551–583. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143932.

- Torroni, Antonio; Schurr, Theodore G.; Yang, Chi-Chuan; et al. (January 1992). "Native American Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Indicates That the Amerind and the Nadene Populations Were Founded by Two Independent Migrations". Genetics. 30 (1): 153–162. doi:10.1093/genetics/130.1.153. PMC 1204788. PMID 1346260.

- Wade, Nicholas (12 March 2014). "Pause Is Seen in a Continent's Peopling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Lyovin, Anatole V. (1997). "Native Languages of the Americas". An Introduction to the Languages of the World. Oxford University. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-19-508115-2. Archived from the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Mithun, Marianne (October 1990). "Studies of North American Indian Languages". Annual Review of Anthropology. 19 (1): 309–330. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001521. JSTOR 2155968.

- Alice Roberts (2010). The Incredible Human Journey. A&C Black. pp. 101–03. ISBN 978-1-4088-1091-0. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- Wang, Sijia; Lewis, Cecil M. Jr.; Jakobsson, Mattias; et al. (23 November 2007). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure in Native Americans". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): e185. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030185. PMC 2082466. PMID 18039031.

- Walsh, Bruce; Redd, Alan J.; Hammer, Michael F. (January 2008). "Joint match probabilities for Y chromosomal and autosomal markers". Forensic Science International. 174 (2–3): 234–238. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.03.014. PMID 17449208.

- Wells, Spencer (2002). The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. Princeton University Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-691-11532-0.

- Hey, Jody (2005). "On the Number of New World Founders: A Population Genetic Portrait of the Peopling of the Americas". PLOS Biology. 3 (6): e193. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030193. PMC 1131883. PMID 15898833.

- Wade, Nicholas (2010-02-11). "Ancient Man In Greenland Has Genome Decoded". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- Reich, David; Patterson, Nick; Campbell, Desmond; et al. (16 August 2012). "Reconstructing Native American population history". Nature. 488 (7411): 370–374. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..370R. doi:10.1038/nature11258. PMC 3615710. PMID 22801491.

- Rasmussen, Morten; Anzick, Sarah L.; Waters, Michael R.; et al. (2014). "The genome of a Late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana". Nature. 506 (7487): 225–229. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..225R. doi:10.1038/nature13025. PMC 4878442. PMID 24522598.

- "Ancient American's genome mapped". BBC News. 2014-02-14. Archived from the original on 2021-05-05. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- Dediu, Dan; Levinson, Stephen C. (20 September 2012). "Abstract Profiles of Structural Stability Point to Universal Tendencies, Family-Specific Factors, and Ancient Connections between Languages". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45198. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745198D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045198. PMC 3447929. PMID 23028843.

- Raghavan, Maanasa; Steinrücken, Matthias; Harris, Kelley; et al. (21 August 2015). "Genomic evidence for the Pleistocene and recent population history of Native Americans". Science. 349 (6250): aab3884. doi:10.1126/science.aab3884. PMC 4733658. PMID 26198033.

- Skoglund, Pontus; Mallick, Swapan; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Chennagiri, Niru; Hünemeier, Tábita; Petzl-Erler, Maria Luiza; Salzano, Francisco Mauro; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (September 2015). "Genetic evidence for two founding populations of the Americas". Nature. 525 (7567): 104–108. Bibcode:2015Natur.525..104S. doi:10.1038/nature14895. PMC 4982469. PMID 26196601.

- Skoglund, Pontus; Reich, David (December 2016). "A genomic view of the peopling of the Americas". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 41: 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2016.06.016. PMC 5161672. PMID 27507099.

- Gakuhari, Takashi; Nakagome, Shigeki; Rasmussen, Simon; et al. (December 2020). "Ancient Jomon genome sequence analysis sheds light on migration patterns of early East Asian populations". Communications Biology. 3 (1): 437. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01162-2. PMC 7447786. PMID 32843717.

- Davis, Loren G.; Madsen, David B.; Becerra-Valdivia, Lorena; et al. (30 August 2019). "Late Upper Paleolithic occupation at Cooper's Ferry, Idaho, USA, ~16,000 years ago". Science. 365 (6456): 891–897. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..891D. doi:10.1126/science.aax9830. PMID 31467216.

- Posth, Cosimo; Nakatsuka, Nathan; Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (November 2018). "Reconstructing the Deep Population History of Central and South America". Cell. 175 (5): 1185–1197.e22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.027. PMC 6327247. PMID 30415837.

- Willerslev, Eske; Meltzer, David J. (17 June 2021). "Peopling of the Americas as inferred from ancient genomics". Nature. 594 (7863): 356–364. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..356W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03499-y. PMID 34135521. S2CID 235460793.

- Sarkar, Anjali A. (2021-06-18). "Ancient Human Genomes Reveal Peopling of the Americas". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

The team discovered that the Spirit Cave remains came from a Native American while dismissing a longstanding theory that a group called Paleoamericans existed in North America before Native Americans.

- Santos, Fabrício R.; Pandya, Arpita; Tyler-Smith, Chris; et al. (February 1999). "The Central Siberian Origin for Native American Y Chromosomes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (2): 619–628. doi:10.1086/302242. PMC 1377773. PMID 9973301.

- Blanco Verea; Alejandro José. Linajes del cromosoma Y humano: aplicaciones genético-poblacionales y forenses. Univ Santiago de Compostela. pp. 135–. GGKEY:JCW0ASCR364. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- "Summary of knowledge on the subclades of Haplogroup Q". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- Zegura, Stephen L.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; et al. (January 2004). "High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single, recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (1): 164–175. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- Saillard, Juliette; Forster, Peter; Lynnerup, Niels; et al. (September 2000). "mtDNA Variation among Greenland Eskimos: The Edge of the Beringian Expansion". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (3): 718–726. doi:10.1086/303038. PMC 1287530. PMID 10924403.

- Schurr, Theodore G. (2004). "The Peopling of the New World – Perspectives from Molecular Anthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 551–583. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143932. JSTOR 25064865. S2CID 4647888.

- Torroni, Antonio; Schurr, Theodore G.; Yang, Chi-Chuan; et al. (January 1992). "Native American Mitochondrial DNA Analysis Indicates That the Amerind and the Nadene Populations Were Founded by Two Independent Migrations". Genetics. 130 (1): 153–162. doi:10.1093/genetics/130.1.153. PMC 1204788. PMID 1346260.

- Balanovsky, Oleg; Gurianov, Vladimir; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; et al. (February 2017). "Phylogeography of human Y-chromosome haplogroup Q3-L275 from an academic/citizen science collaboration". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (S1): 18. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0870-2. PMC 5333174. PMID 28251872.

- "How the Subclades of Y-DNA Haplogroup Q are determined". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- "Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree". Genebase Systems. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- "Frequency Distribution of Y-DNA Haplogroup Q1a3a-M3". GeneTree. 2010. Archived from the original on 2009-11-04. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; Zidkova, Anastassiya; Logacheva, Maria D.; Altınışık, N. Ezgi; Flegontova, Olga; Gelfand, Mikhail S.; Gerasimov, Evgeny S.; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E.; Konovalova, Olga P.; Neretina, Tatiana; Nikolsky, Yuri V.; Starostin, George; Stepanova, Vita V.; Travinsky, Igor V.; Tříska, Martin; Tříska, Petr; Tatarinova, Tatiana V. (2016). "Genomic study of the Ket: A Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6: 20768. arXiv:1508.03097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620768F. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

- "Learning Center :: Genebase Tutorials". Genebase.com. 1964-10-22. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013.

- Bonatto, SL; Salzano, FM (4 March 1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (5): 1866–1871. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1866B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- Smolenyak, Megan; Turner, Ann (2004). Trace Your Roots with DNA: Using Genetic Tests to Explore Your Family Tree. Rodale. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-59486-006-5. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- Than, Ker (14 February 2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Lovgren, Stefan (2 February 2007). "First Americans Arrived Recently, Settled Pacific Coast, DNA Study Says". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover – Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". 2017-05-10. Archived from the original on 2012-10-10. Retrieved 2009-11-18. page 2 Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- González Burchard, Esteban; Borrell, Luisa N.; Choudhry, Shweta; et al. (December 2005). "Latino Populations: A Unique Opportunity for the Study of Race, Genetics, and Social Environment in Epidemiological Research". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (12): 2161–2168. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668. PMC 1449501. PMID 16257940.

- Malhi, Ripan Singh; Gonzalez-Oliver, Angelica; Schroeder, Kari Britt; et al. (10 July 2008). "Distribution of Y Chromosomes Among Native North Americans: A Study of Athapaskan Population History". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (4): 412–424. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20883. PMC 2584155. PMID 18618732.

- Raghavan, Maanasa; Skoglund, Pontus; Graf, Kelly E.; et al. (January 2014). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- Michael Balter (October 2013). "Ancient DNA Links Native Americans With Europe". Science. 342 (6157): 409–410. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..409B. doi:10.1126/science.342.6157.409. PMID 24159019.

- "FamilyTreeDNA - Genetic Testing for Ancestry, Family History & Genealogy". Archived from the original on 2019-06-16. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- Zhong, Hua; Shi, Hong; Qi, Xue-Bin; et al. (July 2010). "Global distribution of Y-chromosome haplogroup C reveals the prehistoric migration routes of African exodus and early settlement in East Asia". Journal of Human Genetics. 55 (7): 428–435. doi:10.1038/jhg.2010.40. PMID 20448651. S2CID 28609578.

- Xue, Yali; Zerjal, Tatiana; Bao, Weidong; et al. (1 April 2006). "Male Demography in East Asia: a North-South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times". Genetics. 172 (4): 2431–2439. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.054270. PMC 1456369. PMID 16489223.

- Marinakis, Aliki (2008). "Na-Dene People". In Johansen, Bruce E.; Pritzker, Barry M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ISOGG, 2015 "Y-DNA Haplogroup C and its Subclades – 2015" Archived 2021-08-15 at the Wayback Machine (15 September 2015).

- Zegura, S. L. (31 October 2003). "High-Resolution SNPs and Microsatellite Haplotypes Point to a Single, Recent Entry of Native American Y Chromosomes into the Americas". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (1): 164–175. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh009. PMID 14595095.

- Bolnick, D. A. (10 August 2006). "Asymmetric Male and Female Genetic Histories among Native Americans from Eastern North America". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (11): 2161–2174. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl088. PMID 16916941. S2CID 30220691.

- Malhi, Ripan Singh; Gonzalez-Oliver, Angelica; Schroeder, Kari Britt; et al. (December 2008). "Distribution of Y chromosomes among Native North Americans: A study of Athapaskan population history". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (4): 412–424. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20883. PMC 2584155. PMID 18618732.

- Dulik, M. C.; Owings, A. C.; Gaieski, J. B.; et al. (14 May 2012). "Y-chromosome analysis reveals genetic divergence and new founding native lineages in Athapaskan- and Eskimoan-speaking populations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (22): 8471–8476. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8471D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1118760109. PMC 3365193. PMID 22586127.

- Hammer, Michael F.; Chamberlain, Veronica F.; Kearney, Veronica F.; et al. (December 2006). "Population structure of Y chromosome SNP haplogroups in the United States and forensic implications for constructing Y chromosome STR databases". Forensic Science International. 164 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.11.013. PMID 16337103.

- Schurr, Theodore G. (May–June 2000). "Mitochondrial DNA and the Peopling of the New World". American Scientist. 88 (3): 246. doi:10.1511/2000.23.772.

- Zakharov, Ilia A.; Derenko, Miroslava V.; Maliarchuk, Boris A.; et al. (April 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in the aboriginal populations of the Altai-Baikal region: implications for the genetic history of North Asia and America". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1011 (1): 21–35. Bibcode:2004NYASA1011...21Z. doi:10.1196/annals.1293.003. PMID 15126280. S2CID 37139929.

- Starikovskaya, Elena B.; Sukernik, Rem I.; Derbeneva, Olga A.; et al. (7 January 2005). "Mitochondrial DNA diversity in indigenous populations of the southern extent of Siberia, and the origins of Native American haplogroups". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (1): 67–89. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00127.x. PMC 3905771. PMID 15638829.

- Ritter, Malcolm (13 March 2008). "Native American DNA Links to Six "Founding Mothers"". National Geographic News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Eshleman, Jason A.; Malhi, Ripan S.; Smith, David Glenn (14 February 2003). "Mitochondrial DNA Studies of Native Americans- Conceptions and Misconceptions of the Population Prehistory of the Americas". Evolutionary Anthropology. 12 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1002/evan.10048. S2CID 17049337.

- Achilli, Alessandro; Perego, Ugo A.; Bravi, Claudio M.; et al. (12 March 2008). "The Phylogeny of the Four Pan-American MtDNA Haplogroups: Implications for Evolutionary and Disease Studies". PLOS ONE. 3 (3): e1764. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1764A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001764. PMC 2258150. PMID 18335039.

- Nina G. Jablonski (2002). The first Americans: the Pleistocene colonization of the New World. University of California Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-940228-50-4. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. 14 August 2009. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2010 – via Phys.org.

- Fagundes, Nelson J.R.; Kanitz, Ricardo; Eckert, Roberta; et al. (3 March 2008). "Mitochondrial Population Genomics Supports a Single Pre-Clovis Origin with a Coastal Route for the Peopling of the Americas". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (3): 583–592. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013. PMC 2427228. PMID 18313026.

- Meltzer, David J. (2009). First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America. University of California Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-520-94315-5. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- "An mtDNA view of the peopling of the world by Homo sapiens". Cambridge DNA. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- Reidla, Maere; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Ene; et al. (November 2003). "Origin and Diffusion of mtDNA Haplogroup X". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (5): 1178–1190. doi:10.1086/379380. PMC 1180497. PMID 14574647.

- "An mtDNA view of the peopling of the world by Homo sapiens". Cambridge DNA Services. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-05-11. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- Peñaloza-Espinosa, Rosenda I.; Arenas-Aranda, Diego; Cerda-Flores, Ricardo M.; et al. (2007). "Characterization of mtDNA Haplogroups in 14 Mexican Indigenous Populations". Human Biology. 79 (3): 313–320. doi:10.1353/hub.2007.0042. PMID 18078204. S2CID 35654242.

- Ferrell, Robert E.; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Gershowitz, Henry; et al. (July 1981). "The St. Lawrence Island Eskimos: Genetic variation and genetic distance". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 55 (3): 351–358. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330550309. PMID 6455922.

- Helgason, Agnar; Pálsson, Gísli; Pedersen, Henning Sloth; et al. (May 2006). "mtDNA variation in Inuit populations of Greenland and Canada: Migration history and population structure". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 130 (1): 123–134. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20313. PMID 16353217.

- Kashani, Baharak Hooshiar; Perego, Ugo A.; Olivieri, Anna; et al. (January 2012). "Mitochondrial haplogroup C4c: A rare lineage entering America through the ice-free corridor?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 147 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21614. PMID 22024980.

- Llamas, Bastien; Fehren-Schmitz, Lars; Valverde, Guido; et al. (29 April 2016). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas". Science Advances. 2 (4): e1501385. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1385L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501385. PMC 4820370. PMID 27051878.

- "Direct genetic evidence of founding population reveals story of first Native Americans". University of Cambridge. 2018-01-03. Archived from the original on 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- "Direct genetic evidence of founding population reveals story of first Native Americans". Archived from the original on 2018-11-05. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- García-Bour, Jaume; Pérez-Pérez, Alejandro; Álvarez, Sara; et al. (2004). "Early population differentiation in extinct aborigines from Tierra del Fuego-Patagonia: Ancient mtDNA sequences and Y-Chromosome STR characterization". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 123 (4): 361–370. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10337. PMID 15022364.

- Neves, W.A.; Powell, J.F.; Ozolins, E.G. (1999). "Extra-continental morphological affinities of Palli Aike, southern Chile". Interciencia. 24 (4): 258–263. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- Bonatto, Sandro L.; Salzano, Francisco M. (4 March 1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 94 (5): 1866–1871. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.1866B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- Willerslev, Eske; Meltzer, David J. (17 June 2021). "Peopling of the Americas as inferred from ancient genomics". Nature. 594 (7863): 356–364. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..356W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03499-y. PMID 34135521. S2CID 235460793.

- Sarkar, Anjali A. (2021-06-18). "Ancient Human Genomes Reveal Peopling of the Americas". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

The team discovered that the Spirit Cave remains came from a Native American while dismissing a longstanding theory that a group called Paleoamericans existed in North America before Native Americans.

- Cinq-Mars, J. (1979). "Bluefish Cave I: A Late Pleistocene Eastern Beringian Cave Deposit in the Northern Yukon". Canadian Journal of Archaeology (3): 1–32. JSTOR 41102194.

- Bonnichsen, Robson (1978). "Critical arguments for Pleistocene artifacts from the Old Crow basin, Yukon: a preliminary statement". In Bryan, Alan Lyle (ed.). Early Man in America from a Circum-pacific Perspective. Archaeological Researches International. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-0-88864-999-7.

- Dillehay, Tom D.; Ocampo, Carlos (2015). "New Archaeological Evidence for an Early Human Presence at Monte Verde, Chile". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0141923. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1041923D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141923. PMC 4651426. PMID 26580202.

- Bourgeon, Lauriane; Burke, Ariane; Higham, Thomas (6 January 2017). "Earliest Human Presence in North America Dated to the Last Glacial Maximum: New Radiocarbon Dates from Bluefish Caves, Canada". PLOS ONE. 12 (1): e0169486. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1269486B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169486. PMC 5218561. PMID 28060931.

- Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Jenkins, Dennis L.; Götherstrom, Anders; et al. (9 May 2008). "DNA from Pre-Clovis Human Coprolites in Oregon, North America". Science. 320 (5877): 786–789. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..786G. doi:10.1126/science.1154116. PMID 18388261. S2CID 17671309.

- Newman, Richard (1999). "Miscegenation". In Kwame Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (ed.). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience (1st ed.). New York: Basic Civitas Books. p. 1320. ISBN 978-0-465-00071-5.

Miscegenation, a term for sexual relations across racial lines; no longer in use because of its racist implications

- Chasteen, John Charles; Wood, James A (2004). Problems in modern Latin American history, sources and interpretations. Sr Books. pp. 4–10. ISBN 978-0-8420-5060-9. Archived from the original on 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- Chasteen (2004:4): "between the White elite and the mass of Amerindians and Negroes there existed by 1700 a thin stratum of population subject neither to Negro slavery nor Amerindian tutelage, consisting of the products of racial interbreeding among Whites, Amerindians, and Negroes and defined as mestizos, mulattoes and zambos (mixture of Indian and Negro) and their many combinations."

- Sans, Mónica (2000). "Admixture Studies in Latin America: From the 20th to the 21st Century". Human Biology. 72 (1): 155–177. JSTOR 41465813. PMID 10721616.

- Sweet, Frank W (2004). "Afro-European Genetic Admixture in the United States". Essays on the Color Line and the One-Drop Rule. Backintyme Essays. Archived from the original on 2010-01-04. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- Sweet, Frank W (2005). Legal History of the Color Line: The Notion of Invisible Blackness. Backintyme Publishing. p. 542. ISBN 978-0-939479-23-8. Archived from the original on 2010-02-17. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- Soong, Roland (1999). "Racial Classifications in Latin America". Latin American Media. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- Brehaut, Harry B (1998). "The Red River Cart and Trails: The Fur Trade". Manitoba Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- "Who are Métis ?". Métis National Council. 2001. Archived from the original on 2010-02-26. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- Adams, Paul (July 10, 2011). "Blood affects US Indian identity". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "Why Do So Many People Claim They Have Cherokee In Their Blood? - Nerve". www.nerve.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Smithers, Gregory D. (October 1, 2015). "Why Do So Many Americans Think They Have Cherokee Blood?". Slate. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "The Cherokee Syndrome - Daily Yonder". www.dailyyonder.com. 10 February 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Hitt, Jack (August 21, 2005). "The Newest Indians". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- Nieves, Evelyn (March 3, 2007). "Putting to a Vote the Question 'Who Is Cherokee?'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.. Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Bill John Baker, reported as of "1/32 Cherokee" ancestry (which would amount to about 3%).

- "What Percentage Indian Do You Have to Be in Order to Be a Member of a Tribe or Nation? - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.. "Disappearing Indians, Part II: The Hypocrisy of Race In Deciding Who's Enrolled - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Price, Michael (15 November 2016). "European diseases left a genetic mark on Native Americans". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aal0382.

- Hershey A, Chase M (1952). "Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage". J Gen Physiol. 36 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1085/jgp.36.1.39. PMC 2147348. PMID 12981234.

- Lille-Szyszkowicz I (1957). "Rozwój badan nad plejadami grup krwi" [Development of studies on pleiades of blood groups]. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej (in Polish). 11 (3): 229–33. OCLC 101713985. PMID 13505351.

- Landsteiner, Karl (1900). "Zur Kenntnis der antifermentativen, lytischen und agglutinierenden Wirkungen des Blutserums und der Lymphe" [Knowledge of the antifermentative, lytic and agglutinating effects of blood serum and lymph]. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie (in German). 27: 357–362. OCLC 11337636. NAID 10008616088.

- Yazer M, Olsson M, Palcic M (2006). "The cis-AB blood group phenotype: fundamental lessons in glycobiology". Transfus Med Rev. 20 (3): 207–17. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.03.002. PMID 16787828.

- "Distribution of Blood Types". Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College. 2010. Archived from the original on 2006-02-21. Retrieved 2010-03-14.

- Estrada-Mena B, Estrada FJ, Ulloa-Arvizu R, et al. (May 2010). "Blood group O alleles in Native Americans: implications in the peopling of the Americas". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21204. PMID 19862808.

- Chown, Bruce; Lewis, Marion (June 1956). "The blood group genes of the Cree Indians and the Eskimos of the ungava district of Canada". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 14 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330140217. PMID 13362488.

- Halverson, Melissa S.; Bolnick, Deborah A. (November 2008). "An ancient DNA test of a founder effect in Native American ABO blood group frequencies". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (3): 342–347. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20887. PMID 18618657.

- "Racial and Ethnic Distribution of ABO Blood Types". BloodBook. 2008. Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- Poole J (2020). "The Diego blood group system-an update". Immunohematology. 15 (4): 135–43. doi:10.21307/immunohematology-2019-635. PMID 15373634.

- Bégat C, Bailly P, Chiaroni J, Mazières S (2015-07-06). "Revisiting the Diego Blood Group System in Amerindians: Evidence for Gene-Culture Comigration". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0132211. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1032211B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132211. PMC 4493026. PMID 26148209.

Further reading

- Peter N. Jones (October 2002). American Indian mtDNA, Y chromosome genetic data, and the peopling of North America. Bauu Institute. ISBN 978-0-9721349-1-0.

- Joseph Frederick Powell (2005). The first Americans: race, evolution, and the origin of Native Americans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82350-0.

- Francisco M. Salzano; Maria Cátira Bortolini (2002). The evolution and genetics of Latin American populations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65275-9.

- "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. University of Oklahoma. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- McInnes, Roderick R. (March 2011). "2010 Presidential Address: Culture: The Silent Language Geneticists Must Learn— Genetic Research with Indigenous Populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (3): 254–261. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.014. PMC 3059421. PMID 21516613.

.svg.png.webp)