Iron overload

Iron overload or hemochromatosis (also spelled haemochromatosis in British English) indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage.[1] The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosis (HH or HHC), a genetic disorder, and transfusional iron overload, which can result from repeated blood transfusions.[2]

| Iron overload | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Haemochromatosis or Hemochromatosis |

| |

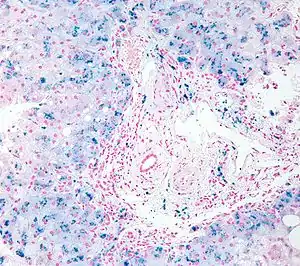

| Micrograph of liver biopsy showing iron deposits due to haemosiderosis. Iron stain. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

Signs and symptoms

Organs most commonly affected by hemochromatosis include the liver, heart, and endocrine glands.[3]

Hemochromatosis may present with the following clinical syndromes:

- liver: chronic liver disease and cirrhosis of the liver.[4]

- heart: heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia.[4]

- hormones: diabetes (see below) and hypogonadism (insufficiency of the sex hormone producing glands) which leads to low sex drive and/or loss of fertility in men and loss of menstrual cycle in women.[4]

- metabolism: diabetes in people with iron overload occurs as a result of selective iron deposition in islet beta cells in the pancreas leading to functional failure and cell death.[5]

- skeletal: arthritis, from calcium pyrophosphate deposition in joints leading to joint pains. The most commonly affected joints are those of the hands, particularly the knuckles of the second and third fingers.[6]

- skin: melanoderma (darkening or 'bronzing' of the skin).[6][7]

The skin's deep tan color, in concert with insulin insufficiency due to pancreatic damage, is the source of a nickname for this condition: "bronze diabetes" (for more information, see the history of hemochromatosis).

Causes

The term hemochromatosis was initially used to refer to what is now more specifically called hemochromatosis type 1 (or HFE-related hereditary hemochromatosis). Currently, hemochromatosis (without further specification) is mostly defined as iron overload with a hereditary or primary cause,[8][9] or originating from a metabolic disorder.[10] However, the term is currently also used more broadly to refer to any form of iron overload, thus requiring specification of the cause, for example, hereditary hemochromatosis. Hereditary hemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disorder with estimated prevalence in the population of 1 in 200 among patients with European ancestry, with lower incidence in other ethnic groups.[11] The gene responsible for hereditary hemochromatosis (known as HFE gene) is located on chromosome 6; the majority of hereditary hemochromatosis patients have mutations in this HFE gene.[1]

Hereditary hemochromatosis is characterized by an accelerated rate of intestinal iron absorption and progressive iron deposition in various tissues. This typically begins to be expressed in the third to fifth decades of life, but may occur in children. The most common presentation is hepatic cirrhosis in combination with hypopituitarism, cardiomyopathy, diabetes, arthritis, or hyperpigmentation. Because of the severe sequelae of this disorder if left untreated, and recognizing that treatment is relatively simple, early diagnosis before symptoms or signs appear is important.[12][13]

In general, the term hemosiderosis is used to indicate the pathological effect of iron accumulation in any given organ, which mainly occurs in the form of the iron-storage complex hemosiderin.[14][15] Sometimes, the simpler term siderosis is used instead.

Other definitions distinguishing hemochromatosis or hemosiderosis that are occasionally used include:

- Hemosiderosis is hemochromatosis caused by excessive blood transfusions, that is, hemosiderosis is a form of secondary hemochromatosis.[16][17]

- Hemosiderosis is hemosiderin deposition within cells, while hemochromatosis is hemosiderin within cells and interstitium.[18]

- Hemosiderosis is iron overload that does not cause tissue damage,[19] while hemochromatosis does.[20]

- Hemosiderosis is arbitrarily differentiated from hemochromatosis by the reversible nature of the iron accumulation in the reticuloendothelial system.[21]

The causes of hemochromatosis broken down into two subcategories: primary cases (hereditary or genetically determined) and less frequent secondary cases (acquired during life).[22] People of Celtic (Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Cornish, Breton etc.), English, and Scandinavian origin[23] have a particularly high incidence, with about 10% being carriers of the principal genetic variant, the C282Y mutation on the HFE gene, and 1% having the condition.[24] This has been recognized in several layman's alternative names such as Celtic curse, Irish illness, British gene, and Scottish sickness.

The overwhelming majority depend on mutations of the HFE gene discovered in 1996, but since then others have been discovered and sometimes are grouped together as "non-classical hereditary hemochromatosis",[25] "non-HFE related hereditary hemochromatosis",[26] or "non-HFE hemochromatosis".[27]

| Description | OMIM | Mutation |

| Hemochromatosis type 1: "classical" hemochromatosis | 235200 | HFE |

| Hemochromatosis type 2A: juvenile hemochromatosis | 602390 | Haemojuvelin (HJV, also known as RGMc and HFE2) |

| Hemochromatosis type 2B: juvenile hemochromatosis | 606464 | hepcidin antimicrobial peptide (HAMP) or HFE2B |

| Hemochromatosis type 3 | 604250 | transferrin receptor-2 (TFR2 or HFE3) |

| Hemochromatosis type 4 / African iron overload | 604653 | ferroportin (SLC11A3/SLC40A1) |

| Neonatal hemochromatosis | 231100 | (unknown) |

| Acaeruloplasminaemia (very rare) | 604290 | caeruloplasmin |

| Congenital atransferrinaemia (very rare) | 209300 | transferrin |

| GRACILE syndrome (very rare) | 603358 | BCS1L |

Most types of hereditary hemochromatosis have autosomal recessive inheritance, while type 4 has autosomal dominant inheritance.[28]

Secondary hemochromatosis

- Severe chronic hemolysis of any cause, including intravascular hemolysis and ineffective erythropoiesis (hemolysis within the bone marrow)

- Multiple frequent blood transfusions (either whole blood or just red blood cells), which are usually needed either by individuals with hereditary anaemias (such as beta-thalassaemia major, sickle cell anaemia, and Diamond–Blackfan anaemia) or by older patients with severe acquired anaemias such as in myelodysplastic syndromes.[5]

- Excess parenteral (non-ingested) iron supplements, such as what can acutely happen in iron poisoning

- Excess dietary iron

- Some disorders do not normally cause hemochromatosis on their own, but may do so in the presence of other predisposing factors. These include cirrhosis (especially related to alcohol use disorder), steatohepatitis of any cause, porphyria cutanea tarda, prolonged hemodialysis, and post-portacaval shunting

Diagnosis

_in_pancreatic_islet_beta_cells(red)_from_transfusional_hemochromatosis_autopsy_cases_versus_that_of_controls_(right_lower_one).jpg.webp)

There are several methods available for diagnosing and monitoring iron loading.

Blood test

Blood tests are usually the first test if there is a clinical suspicion of iron overload. Serum ferritin testing is a low-cost, readily available, and minimally invasive method for assessing body iron stores. However, the major problem with using it as an indicator of iron overload is that it can be elevated in a variety of other medical conditions including infection, inflammation, fever, liver disease, kidney disease, and cancer. Also, total iron binding capacity may be low, but can also be normal.[29] In males and postmenopausal females, normal range of serum ferritin is between 12 and 300 ng/mL (670 pmol/L) .[30][31][32] In premenopausal females, normal range of serum ferritin is between 12 and 150[30] or 200[31] ng/mL (330 or 440 pmol/L).[32] If the person is showing the symptoms, they may need to be tested more than once throughout their lives as a precaution, most commonly in women after menopause. Transferrin saturation is a more specific test.

Genetics

DNA/screening: the current standard of practice in diagnosis of hemochromatosis, places emphasis on genetic testing.[12] Positive HFE analysis confirms the clinical diagnosis of hemochromatosis in asymptomatic individuals with blood tests showing increased iron stores, or for predictive testing of individuals with a family history of hemochromatosis. The alleles evaluated by HFE gene analysis are evident in ~80% of patients with hemochromatosis; a negative report for HFE gene does not rule out hemochromatosis. First degree relatives of those with primary hemochromatosis should be screened to determine if they are a carrier or if they could develop the disease. This can allow preventive measures to be taken. Screening the general population is not recommended.[33]

Biopsy

Liver biopsy is the removal of small sample in order to be studied and can determine the cause of inflammation or cirrhosis. In someone with negative HFE gene testing, elevated iron status for no other obvious reason, and family history of liver disease, additional evaluation of liver iron concentration is indicated. In this case, diagnosis of hemochromatosis is based on biochemical analysis and histologic examination of a liver biopsy. Assessment of the hepatic iron index (HII) is considered the "gold standard" for diagnosis of hemochromatosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used as a noninvasive way to accurately estimate iron deposition levels in the liver as well as heart, joints, and pituitary gland.

Treatment

Phlebotomy

Phlebotomy/venesection: routine treatment consists of regularly scheduled phlebotomies (bloodletting or erythrocytapheresis). When first diagnosed, the phlebotomies may be performed every week or fortnight, until iron levels can be brought to within normal range. Once the serum ferritin and transferrin saturation are within the normal range, treatments may be scheduled every two to three months depending upon the rate of reabsorption of iron. A phlebotomy session typically draws between 450 and 500 mL of blood.[35] The blood drawn is sometimes donated.[36]

Diet

A diet low in iron is generally recommended, but has little effect compared to venesection. The human diet contains iron in two forms: heme iron and non-heme iron. Heme iron is the most easily absorbed form of iron. People with iron overload may be advised to avoid food that are high in heme iron. Highest in heme iron is red meat such as beef, venison, lamb, buffalo, and fish such as bluefin tuna. A strict low-iron diet is usually not necessary. Non-heme iron is not as easily absorbed in the human system and is found in plant-based foods such as grains, beans, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds.[37]

Medication

Medication: For those unable to tolerate routine blood draws, there are chelating agents available for use.[38] The drug deferoxamine binds with iron in the bloodstream and enhances its elimination in urine and faeces. Typical treatment for chronic iron overload requires subcutaneous injection over a period of 8–12 hours daily. Two newer iron-chelating drugs that are licensed for use in patients receiving regular blood transfusions to treat thalassaemia (and, thus, who develop iron overload as a result) are deferasirox and deferiprone.[39][40]

Chelating polymers

A minimally invasive approach to hereditary hemochromatosis treatment is the maintenance therapy with polymeric chelators.[41][42][43] These polymers or particles have a negligible or null systemic biological availability and they are designed to form stable complexes with Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the GIT and thus limiting their uptake and long-term accumulation. Although this method has only a limited efficacy, unlike small-molecular chelators, the approach has virtually no side effects in sub-chronic studies.[43] Interestingly, the simultaneous chelation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ increases the treatment efficacy.[43]

Prognosis

In general, provided there has been no liver damage, patients should expect a normal life expectancy if adequately treated by venesection. If the serum ferritin is greater than 1000 ug/L at diagnosis there is a risk of liver damage and cirrhosis which may eventually shorten their life.[44] The presence of cirrhosis increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.[45]

Epidemiology

HHC is most common in certain European populations (such as those of Irish or Scandinavian descent) and occurs in 0.6% of some unspecified population.[33] Men have a 24-fold increased rate of iron-overload disease compared with women.[33]

Stone Age

Diet and the environment are thought to have had large influence on the mutation of genes related to iron overload. Starting during the Mesolithic era, communities of people lived in an environment that was fairly sunny, warm and had the dry climates of the Middle East. Most humans who lived at that time were foragers and their diets consisted largely of game, fish and wild plants. Archaeologists studying dental plaque have found evidence of tubers, nuts, plantains, grasses and other foods rich in iron. Over many generations, the human body became well-adapted to a high level of iron content in the diet.[46]

Neolithic

In the Neolithic era, significant changes are thought to have occurred in both the environment and diet. Some communities of foragers migrated north, leading to changes in lifestyle and environment, with a decrease in temperatures and a change in the landscape which the foragers then needed to adapt to. As people began to develop and advance their tools, they learned new ways of producing food, and farming also slowly developed. These changes would have led to serious stress on the body and a decrease in the consumption of iron-rich foods. This transition is a key factor in the mutation of genes, especially those that regulated dietary iron absorption. Iron, which makes up 70% of red blood cell composition, is a critical micronutrient for effective thermoregulation in the body.[47] Iron deficiency will lead to a drop in the core temperature. In the chilly and damp environments of Northern Europe, supplementary iron from food was necessary to keep temperatures regulated, however, without sufficient iron intake the human body would have started to store iron at higher rates than normal. In theory, the pressures caused by migrating north would have selected for a gene mutation that promoted greater absorption and storage of iron.[48]

Viking hypothesis

Studies and surveys conducted to determine the frequencies of hemochromatosis help explain how the mutation migrated around the globe. In theory, the disease initially evolved from travelers migrating from the north. Surveys show a particular distribution pattern with large clusters and frequencies of gene mutations along the western European coastline.[49] This led the development of the "Viking Hypothesis".[50] Cluster locations and mapped patterns of this mutation correlate closely to the locations of Viking settlements in Europe established c.700 AD to c.1100 AD. The Vikings originally came from Norway, Sweden and Denmark. Viking ships made their way along the coastline of Europe in search of trade, riches, and land. Genetic studies suggest that the extremely high frequency patterns in some European countries are the result of migrations of Vikings and later Normans, indicating a genetic link between hereditary hemochromatosis and Viking ancestry.[51]

Modern times

In 1865, Armand Trousseau (a French internist) was one of the first to describe many of the symptoms of a diabetic patient with cirrhosis of the liver and bronzed skin color. The term hemochromatosis was first used by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen in 1889 when he described an accumulation of iron in body tissues.[52]

Identification of genetic factors

Although it was known most of the 20th century that most cases of hemochromatosis were inherited, they were incorrectly assumed to depend on a single gene.[53]

In 1935 J.H. Sheldon, a British physician, described the link to iron metabolism for the first time as well as demonstrating its hereditary nature.[52]

In 1996 Felder and colleagues identified the hemochromatosis gene, HFE gene. Felder found that the HFE gene has two main mutations, C282Y and H63D, which were the main cause of hereditary hemochromatosis.[52][54] The next year the CDC and the National Human Genome Research Institute sponsored an examination of hemochromatosis following the discovery of the HFE gene, which helped lead to the population screenings and estimates that are still being used today.[55]

See also

References

- Hsu CC, Senussi NH, Fertrin KY, Kowdley KV (June 2022). "Iron overload disorders". Hepatol Commun. doi:10.1002/hep4.2012. PMID 35699322.

- Hider, Robert C.; Kong, Xiaole (2013). "Chapter 8. Iron: Effect of Overload and Deficiency". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel (ed.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 229–294. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_8. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470094.

- Andrews, Nancy C. (1999). "Disorders of Iron Metabolism". New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (26): 1986–95. doi:10.1056/NEJM199912233412607. PMID 10607817.

- John Murtagh (2007). General Practice. McGraw Hill Australia. ISBN 978-0-07-470436-3.

- Lu, JP (1994). "Selective iron deposition in pancreatic islet B cells of transfusional iron‐overloaded autopsy cases". Pathol Int. 44 (3): 194–199. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb02592.x. PMID 8025661. S2CID 25357672.

- Bruce R Bacon, Stanley L Schrier. "Patient information: Hemochromatosis (hereditary iron overload) (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Retrieved 2016-07-14. Literature review current through: Jun 2016. | This topic last updated: Apr 14, 2015.

- Brissot, P; Pietrangelo, A; Adams, PC; de Graaff, B; McLaren, CE; Loréal, O (5 April 2018). "Haemochromatosis". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 4: 18016. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2018.16. PMC 7775623. PMID 29620054.

- thefreedictionary.com > hemochromatosis, citing:

- The American Heritage Medical Dictionary, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company

- McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. 2002

- Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary > hemochromatosis Retrieved on December 11, 2009

- thefreedictionary.com, citing:

- Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers, 2007

- Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. 2009

- Jonas: Mosby's Dictionary of Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005.

- "Hemochromatosis". Archived from the original on 2007-03-18. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- Pietrangelo, Antonello (2010). "Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Gastroenterology. 139 (2): 393–408. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.013. PMID 20542038.

- Brandhagen, D J; Fairbanks, V F; Batts, K P; Thibodeau, S N (1999). "Update on hereditary hemochromatosis and the HFE gene". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 74 (9): 917–21. doi:10.4065/74.9.917. PMID 10488796.

- Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary > hemosideroses Retrieved on December 11, 2009

- thefreedictionary.com > hemosiderosis, citing:

- The American Heritage Medical Dictionary, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company

- Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition.

- eMedicine Specialties > Radiology > Gastrointestinal > Hemochromatosis Author: Sandor Joffe, MD. Updated: May 8, 2009

- thefreedictionary.com > hemosiderosis, citing:

- Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008

- Notecards on radiology gamuts, diseases, anatomy Archived 2010-07-21 at the Wayback Machine 2002, Charles E. Kahn, Jr., MD. Medical College of Wisconsin

- thefreedictionary.com > hemosiderosis, citing:

- Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers, 2007

- Mosby's Dental Dictionary, 2nd edition.

- Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, 3rd ed. 2007

- The HealthScout Network > Health Encyclopedia > Diseases and Conditions > Hemochromatosis Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on December 11, 2009

- thefreedictionary.com > hemosiderosis, citing:

- McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. 2002

- Pietrangelo, A (2003). "Haemochromatosis". Gut. 52 (90002): ii23–30. doi:10.1136/gut.52.suppl_2.ii23. PMC 1867747. PMID 12651879.

- The Atlantic: "The Iron in Our Blood That Keeps and Kills Us" by Bradley Wertheim January 10, 2013

- "Hemachromatosis". Encyclopædia Britannica.com. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Mendes, Ana Isabel; Ferro, Ana; Martins, Rute; Picanço, Isabel; Gomes, Susana; Cerqueira, Rute; Correia, Manuel; Nunes, António Robalo; Esteves, Jorge; Fleming, Rita; Faustino, Paula (2008). "Non-classical hereditary hemochromatosis in Portugal: novel mutations identified in iron metabolism-related genes" (PDF). Annals of Hematology. 88 (3): 229–34. doi:10.1007/s00277-008-0572-y. PMID 18762941. S2CID 23206256.

- Maddrey, Willis C.; Schiff, Eugene R.; Sorrell, Michael F. (2007). Schiff's diseases of the liver. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1048. ISBN 978-0-7817-6040-9.

- Pietrangelo, Antonello (2005). "Non-HFE Hemochromatosis". Seminars in Liver Disease. 25 (4): 450–60. doi:10.1055/s-2005-923316. PMID 16315138.

- Franchini, Massimo (2006). "Hereditary iron overload: Update on pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment". American Journal of Hematology. 81 (3): 202–9. doi:10.1002/ajh.20493. PMID 16493621.

- labtestsonline.org TIBC & UIBC, Transferrin Last reviewed on October 28, 2009.

- Ferritin by: Mark Levin, MD, Hematologist and Oncologist, Newark, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network

- Andrea Duchini. "Hemochromatosis Workup". Medscape. Retrieved 2016-07-14. Updated: Jan 02, 2016

- Molar concentration is derived from mass value using molar mass of 450,000 g•mol−1 for ferritin

- Crownover, BK; Covey, CJ (Feb 1, 2013). "Hereditary hemochromatosis". American Family Physician. 87 (3): 183–90. PMID 23418762.

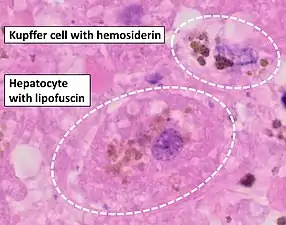

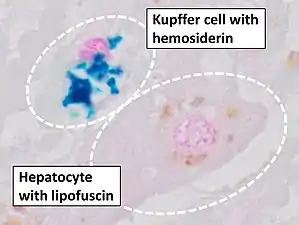

- Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. Source for mesenchymal versus parenchymal iron overload Deugnier Y, Turlin B (2007). "Pathology of hepatic iron overload". World J Gastroenterol. 13 (35): 4755–60. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i35.4755. PMC 4611197. PMID 17729397.

- Barton, James C. (1 December 1998). "Management of Hemochromatosis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 129 (11_Part_2): 932–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-129-11_Part_2-199812011-00003. PMID 9867745. S2CID 53087679.

- NIH blood bank. "Hemochromatosis Donor Program".

- "Welcome". Hemochromatosis.org - An Education Website for Hemochromatosis and Too Much Iron. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Miller, Marvin J. (1989-11-01). "Syntheses and therapeutic potential of hydroxamic acid based siderophores and analogs". Chemical Reviews. 89 (7): 1563–1579. doi:10.1021/cr00097a011.

- Choudhry VP, Naithani R (2007). "Current status of iron overload and chelation with deferasirox". Indian J Pediatr. 74 (8): 759–64. doi:10.1007/s12098-007-0134-7. PMID 17785900. S2CID 19930076.

- Hoffbrand, A. V. (20 March 2003). "Role of deferiprone in chelation therapy for transfusional iron overload". Blood. 102 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-06-1867. PMID 12637334.

- Polomoscanik, Steven C.; Cannon, C. Pat; Neenan, Thomas X.; Holmes-Farley, S. Randall; Mandeville, W. Harry; Dhal, Pradeep K. (2005). "Hydroxamic Acid-Containing Hydrogels for Nonabsorbed Iron Chelation Therapy: Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Evaluation". Biomacromolecules. 6 (6): 2946–2953. doi:10.1021/bm050036p. ISSN 1525-7797. PMID 16283713.

- Qian, Jian; Sullivan, Bradley P.; Peterson, Samuel J.; Berkland, Cory (2017). "Nonabsorbable Iron Binding Polymers Prevent Dietary Iron Absorption for the Treatment of Iron Overload". ACS Macro Letters. 6 (4): 350–353. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00945. ISSN 2161-1653. PMID 35610854.

- Groborz, Ondřej; Poláková, Lenka; Kolouchová, Kristýna; Švec, Pavel; Loukotová, Lenka; Miriyala, Vijay Madhav; Francová, Pavla; Kučka, Jan; Krijt, Jan; Páral, Petr; Báječný, Martin; Heizer, Tomáš; Pohl, Radek; Dunlop, David; Czernek, Jiří; Šefc, Luděk; Beneš, Jiří; Štěpánek, Petr; Hobza, Pavel; Hrubý, Martin (2020). "Chelating Polymers for Hereditary Hemochromatosis Treatment". Macromolecular Bioscience. 20 (12): 2000254. doi:10.1002/mabi.202000254. ISSN 1616-5187. PMID 32954629. S2CID 221827050.

- Allen, KJ; Gurrin, LC; Constantine, CC; Osborne, NJ; Delatycki, MB; Nicoll, AJ; McLaren, CE; Bahlo, M; Nisselle, AE; Vulpe, CD; Anderson, GJ; Southey, MC; Giles, GG; English, DR; Hopper, JL; Olynyk, JK; Powell, LW; Gertig, DM (17 January 2008). "Iron-overload-related disease in HFE hereditary hemochromatosis" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (3): 221–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073286. PMID 18199861.

- Kowdley, KV (November 2004). "Iron, hemochromatosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma". Gastroenterology. 127 (5 Suppl 1): S79–86. doi:10.1016/j.gastro.2004.09.019. PMID 15508107.

- "The Evolution of Diet". National Geographic. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Rosenzweig, P. H.; Volpe, S. L. (March 1999). "Iron, thermoregulation, and metabolic rate". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 39 (2): 131–148. doi:10.1080/10408399908500491. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 10198751.

- Heath, Kathleen M.; Axton, Jacob H.; McCullough, John M.; Harris, Nathan (May 2016). "The evolutionary adaptation of the C282Y mutation to culture and climate during the European Neolithic". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 160 (1): 86–101. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22937. ISSN 0002-9483. PMC 5066702. PMID 26799452.

- "Clinical Penetrance of HFE Hereditary Hemochromatosis, Serum Ferritin Levels, and Screening Implications: Can We Iron This Out?". www.hematology.org. 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Symonette, Caitlin J; Adams, Paul C (June 2011). "Do all hemochromatosis patients have the same origin? A pilot study of mitochondrial DNA and Y-DNA". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 25 (6): 324–326. doi:10.1155/2011/463810. ISSN 0835-7900. PMC 3142605. PMID 21766093.

- "Videos: Hereditary Hemochromatosis | Canadian Hemochromatosis Society". www.toomuchiron.ca. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- Fitzsimons, Edward J.; Cullis, Jonathan O.; Thomas, Derrick W.; Tsochatzis, Emmanouil; Griffiths, William J. H.; the British Society for Haematology (May 2018). "Diagnosis and therapy of genetic haemochromatosis (review and 2017 update)". British Journal of Haematology. 181 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/bjh.15164. PMID 29663319.

- Cam Patterson; Marschall S. Runge (2006). Principles of molecular medicine. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 567. ISBN 978-1-58829-202-5.

- Feder, J.N.; Gnirke, A.; Thomas, W.; Tsuchihashi, Z.; Ruddy, D.A.; Basava, A.; Dormishian, F.; Domingo, R.; Ellis, M.C. (August 1996). "A novel MHC class I–like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis". Nature Genetics. 13 (4): 399–408. doi:10.1038/ng0896-399. PMID 8696333. S2CID 26239768.

- Burke, Wylie; Thomson, Elizabeth; Khoury, Muin J.; McDonnell, Sharon M.; Press, Nancy; Adams, Paul C.; Barton, James C.; Beutler, Ernest; Brittenham, Gary (1998-07-08). "Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Gene Discovery and Its Implications for Population-Based Screening". JAMA. 280 (2): 172–8. doi:10.1001/jama.280.2.172. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 9669792.