Isosceles triangle

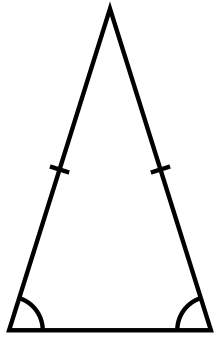

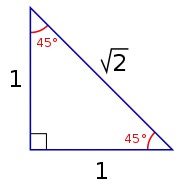

In geometry, an isosceles triangle (/aɪˈsɒsəliːz/) is a triangle that has at least two sides of equal length. Sometimes it is specified as having exactly two sides of equal length, and sometimes as having at least two sides of equal length, the latter version thus including the equilateral triangle as a special case. Examples of isosceles triangles include the isosceles right triangle, the golden triangle, and the faces of bipyramids and certain Catalan solids.

| Isosceles triangle | |

|---|---|

Isosceles triangle with vertical axis of symmetry | |

| Type | triangle |

| Edges and vertices | 3 |

| Schläfli symbol | ( ) ∨ { } |

| Symmetry group | Dih2, [ ], (*), order 2 |

| Properties | convex, cyclic |

The mathematical study of isosceles triangles dates back to ancient Egyptian mathematics and Babylonian mathematics. Isosceles triangles have been used as decoration from even earlier times, and appear frequently in architecture and design, for instance in the pediments and gables of buildings.

The two equal sides are called the legs and the third side is called the base of the triangle. The other dimensions of the triangle, such as its height, area, and perimeter, can be calculated by simple formulas from the lengths of the legs and base. Every isosceles triangle has an axis of symmetry along the perpendicular bisector of its base. The two angles opposite the legs are equal and are always acute, so the classification of the triangle as acute, right, or obtuse depends only on the angle between its two legs.

Terminology, classification, and examples

Euclid defined an isosceles triangle as a triangle with exactly two equal sides,[1] but modern treatments prefer to define isosceles triangles as having at least two equal sides. The difference between these two definitions is that the modern version makes equilateral triangles (with three equal sides) a special case of isosceles triangles.[2] A triangle that is not isosceles (having three unequal sides) is called scalene.[3] "Isosceles" is made from the Greek roots "isos" (equal) and "skelos" (leg). The same word is used, for instance, for isosceles trapezoids, trapezoids with two equal sides,[4] and for isosceles sets, sets of points every three of which form an isosceles triangle.[5]

In an isosceles triangle that has exactly two equal sides, the equal sides are called legs and the third side is called the base. The angle included by the legs is called the vertex angle and the angles that have the base as one of their sides are called the base angles.[6] The vertex opposite the base is called the apex.[7] In the equilateral triangle case, since all sides are equal, any side can be called the base.[8]

Whether an isosceles triangle is acute, right or obtuse depends only on the angle at its apex. In Euclidean geometry, the base angles can not be obtuse (greater than 90°) or right (equal to 90°) because their measures would sum to at least 180°, the total of all angles in any Euclidean triangle.[8] Since a triangle is obtuse or right if and only if one of its angles is obtuse or right, respectively, an isosceles triangle is obtuse, right or acute if and only if its apex angle is respectively obtuse, right or acute.[7] In Edwin Abbott's book Flatland, this classification of shapes was used as a satire of social hierarchy: isosceles triangles represented the working class, with acute isosceles triangles higher in the hierarchy than right or obtuse isosceles triangles.[9]

As well as the isosceles right triangle, several other specific shapes of isosceles triangles have been studied. These include the Calabi triangle (a triangle with three congruent inscribed squares),[10] the golden triangle and golden gnomon (two isosceles triangles whose sides and base are in the golden ratio),[11] the 80-80-20 triangle appearing in the Langley's Adventitious Angles puzzle,[12] and the 30-30-120 triangle of the triakis triangular tiling. Five Catalan solids, the triakis tetrahedron, triakis octahedron, tetrakis hexahedron, pentakis dodecahedron, and triakis icosahedron, each have isosceles-triangle faces, as do infinitely many pyramids[8] and bipyramids.[13]

Formulas

Height

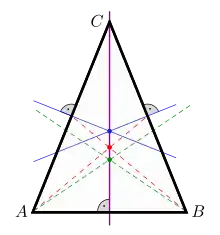

For any isosceles triangle, the following six line segments coincide:

- the altitude, a line segment from the apex perpendicular to the base,[14]

- the angle bisector from the apex to the base,[14]

- the median from the apex to the midpoint of the base,[14]

- the perpendicular bisector of the base within the triangle,[14]

- the segment within the triangle of the unique axis of symmetry of the triangle, and[14]

- the segment within the triangle of the Euler line of the triangle, except when the triangle is equilateral.[15]

Their common length is the height of the triangle. If the triangle has equal sides of length and base of length , the general triangle formulas for the lengths of these segments all simplify to[16]

This formula can also be derived from the Pythagorean theorem using the fact that the altitude bisects the base and partitions the isosceles triangle into two congruent right triangles.[17]

The Euler line of any triangle goes through the triangle's orthocenter (the intersection of its three altitudes), its centroid (the intersection of its three medians), and its circumcenter (the intersection of the perpendicular bisectors of its three sides, which is also the center of the circumcircle that passes through the three vertices). In an isosceles triangle with exactly two equal sides, these three points are distinct, and (by symmetry) all lie on the symmetry axis of the triangle, from which it follows that the Euler line coincides with the axis of symmetry. The incenter of the triangle also lies on the Euler line, something that is not true for other triangles.[15] If any two of an angle bisector, median, or altitude coincide in a given triangle, that triangle must be isosceles.[18]

Area

The area of an isosceles triangle can be derived from the formula for its height, and from the general formula for the area of a triangle as half the product of base and height:[16]

The same area formula can also be derived from Heron's formula for the area of a triangle from its three sides. However, applying Heron's formula directly can be numerically unstable for isosceles triangles with very sharp angles, because of the near-cancellation between the semiperimeter and side length in those triangles.[19]

If the apex angle and leg lengths of an isosceles triangle are known, then the area of that triangle is:[20]

This is a special case of the general formula for the area of a triangle as half the product of two sides times the sine of the included angle.[21]

Perimeter

The perimeter of an isosceles triangle with equal sides and base is just[16]

As in any triangle, the area and perimeter are related by the isoperimetric inequality[22]

This is a strict inequality for isosceles triangles with sides unequal to the base, and becomes an equality for the equilateral triangle. The area, perimeter, and base can also be related to each other by the equation[23]

If the base and perimeter are fixed, then this formula determines the area of the resulting isosceles triangle, which is the maximum possible among all triangles with the same base and perimeter.[24] On the other hand, if the area and perimeter are fixed, this formula can be used to recover the base length, but not uniquely: there are in general two distinct isosceles triangles with given area and perimeter . When the isoperimetric inequality becomes an equality, there is only one such triangle, which is equilateral.[25]

Angle bisector length

If the two equal sides have length and the other side has length , then the internal angle bisector from one of the two equal-angled vertices satisfies[26]

as well as

and conversely, if the latter condition holds, an isosceles triangle parametrized by and exists.[27]

The Steiner–Lehmus theorem states that every triangle with two angle bisectors of equal lengths is isosceles. It was formulated in 1840 by C. L. Lehmus. Its other namesake, Jakob Steiner, was one of the first to provide a solution.[28] Although originally formulated only for internal angle bisectors, it works for many (but not all) cases when, instead, two external angle bisectors are equal. The 30-30-120 isosceles triangle makes a boundary case for this variation of the theorem, as it has four equal angle bisectors (two internal, two external).[29]

Radii

The inradius and circumradius formulas for an isosceles triangle may be derived from their formulas for arbitrary triangles.[30] The radius of the inscribed circle of an isosceles triangle with side length , base , and height is:[16]

The center of the circle lies on the symmetry axis of the triangle, this distance above the base. An isosceles triangle has the largest possible inscribed circle among the triangles with the same base and apex angle, as well as also having the largest area and perimeter among the same class of triangles.[31]

The radius of the circumscribed circle is:[16]

The center of the circle lies on the symmetry axis of the triangle, this distance below the apex.

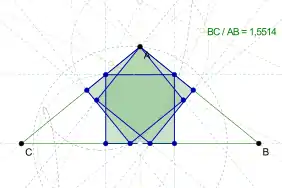

Inscribed square

For any isosceles triangle, there is a unique square with one side collinear with the base of the triangle and the opposite two corners on its sides. The Calabi triangle is a special isosceles triangle with the property that the other two inscribed squares, with sides collinear with the sides of the triangle, are of the same size as the base square.[10] A much older theorem, preserved in the works of Hero of Alexandria, states that, for an isosceles triangle with base and height , the side length of the inscribed square on the base of the triangle is[32]

Isosceles subdivision of other shapes

For any integer , any triangle can be partitioned into isosceles triangles.[33] In a right triangle, the median from the hypotenuse (that is, the line segment from the midpoint of the hypotenuse to the right-angled vertex) divides the right triangle into two isosceles triangles. This is because the midpoint of the hypotenuse is the center of the circumcircle of the right triangle, and each of the two triangles created by the partition has two equal radii as two of its sides.[34] Similarly, an acute triangle can be partitioned into three isosceles triangles by segments from its circumcenter,[35] but this method does not work for obtuse triangles, because the circumcenter lies outside the triangle.[30]

Generalizing the partition of an acute triangle, any cyclic polygon that contains the center of its circumscribed circle can be partitioned into isosceles triangles by the radii of this circle through its vertices. The fact that all radii of a circle have equal length implies that all of these triangles are isosceles. This partition can be used to derive a formula for the area of the polygon as a function of its side lengths, even for cyclic polygons that do not contain their circumcenters. This formula generalizes Heron's formula for triangles and Brahmagupta's formula for cyclic quadrilaterals.[36]

Either diagonal of a rhombus divides it into two congruent isosceles triangles. Similarly, one of the two diagonals of a kite divides it into two isosceles triangles, which are not congruent except when the kite is a rhombus.[37]

Applications

In architecture and design

Isosceles triangles commonly appear in architecture as the shapes of gables and pediments. In ancient Greek architecture and its later imitations, the obtuse isosceles triangle was used; in Gothic architecture this was replaced by the acute isosceles triangle.[8]

In the architecture of the Middle Ages, another isosceles triangle shape became popular: the Egyptian isosceles triangle. This is an isosceles triangle that is acute, but less so than the equilateral triangle; its height is proportional to 5/8 of its base.[38] The Egyptian isosceles triangle was brought back into use in modern architecture by Dutch architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage.[39]

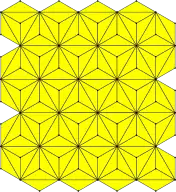

Warren truss structures, such as bridges, are commonly arranged in isosceles triangles, although sometimes vertical beams are also included for additional strength.[40] Surfaces tessellated by obtuse isosceles triangles can be used to form deployable structures that have two stable states: an unfolded state in which the surface expands to a cylindrical column, and a folded state in which it folds into a more compact prism shape that can be more easily transported.[41] The same tessellation pattern forms the basis of Yoshimura buckling, a pattern formed when cylindrical surfaces are axially compressed,[42] and of the Schwarz lantern, an example used in mathematics to show that the area of a smooth surface cannot always be accurately approximated by polyhedra converging to the surface.[43]

In graphic design and the decorative arts, isosceles triangles have been a frequent design element in cultures around the world from at least the Early Neolithic[44] to modern times.[45] They are a common design element in flags and heraldry, appearing prominently with a vertical base, for instance, in the flag of Guyana, or with a horizontal base in the flag of Saint Lucia, where they form a stylized image of a mountain island.[46]

They also have been used in designs with religious or mystic significance, for instance in the Sri Yantra of Hindu meditational practice.[47]

In other areas of mathematics

If a cubic equation with real coefficients has three roots that are not all real numbers, then when these roots are plotted in the complex plane as an Argand diagram they form vertices of an isosceles triangle whose axis of symmetry coincides with the horizontal (real) axis. This is because the complex roots are complex conjugates and hence are symmetric about the real axis.[48]

In celestial mechanics, the three-body problem has been studied in the special case that the three bodies form an isosceles triangle, because assuming that the bodies are arranged in this way reduces the number of degrees of freedom of the system without reducing it to the solved Lagrangian point case when the bodies form an equilateral triangle. The first instances of the three-body problem shown to have unbounded oscillations were in the isosceles three-body problem.[49]

History and fallacies

Long before isosceles triangles were studied by the ancient Greek mathematicians, the practitioners of Ancient Egyptian mathematics and Babylonian mathematics knew how to calculate their area. Problems of this type are included in the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus and Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[50]

The theorem that the base angles of an isosceles triangle are equal appears as Proposition I.5 in Euclid.[51] This result has been called the pons asinorum (the bridge of asses) or the isosceles triangle theorem. Rival explanations for this name include the theory that it is because the diagram used by Euclid in his demonstration of the result resembles a bridge, or because this is the first difficult result in Euclid, and acts to separate those who can understand Euclid's geometry from those who cannot.[52]

A well-known fallacy is the false proof of the statement that all triangles are isosceles. Robin Wilson credits this argument to Lewis Carroll,[53] who published it in 1899, but W. W. Rouse Ball published it in 1892 and later wrote that Carroll obtained the argument from him.[54] The fallacy is rooted in Euclid's lack of recognition of the concept of betweenness and the resulting ambiguity of inside versus outside of figures.[55]

Notes

- Heath (1956), p. 187, Definition 20.

- Stahl (2003), p. 37.

- Usiskin & Griffin (2008), p. 4.

- Usiskin & Griffin (2008), p. 41.

- Ionin (2009).

- Jacobs (1974), p. 144.

- Gottschau, Haverkort & Matzke (2018).

- Lardner (1840), p. 46.

- Barnes (2012).

- Conway & Guy (1996).

- Loeb (1992).

- Langley (1922).

- Montroll (2009).

- Hadamard (2008), p. 23.

- Guinand (1984).

- Harris & Stöcker (1998), p. 78.

- Salvadori & Wright (1998).

- Hadamard (2008), Exercise 5, p. 29.

- Kahan (2014).

- Young (2011), p. 298.

- Young (2011), p. 398.

- Alsina & Nelsen (2009), p. 71.

- Baloglou & Helfgott (2008), Equation (1).

- Wickelgren (2012).

- Baloglou & Helfgott (2008), Theorem 2.

- Arslanagić.

- Oxman (2005).

- Gilbert & MacDonnell (1963).

- Conway & Ryba (2014).

- Harris & Stöcker (1998), p. 75.

- Alsina & Nelsen (2009), p. 67.

- Gandz (1940).

- Lord (1982). See also Hadamard (2008, Exercise 340, p. 270).

- Posamentier & Lehmann (2012), p. 24.

- Bezdek & Bisztriczky (2015).

- Robbins (1995).

- Usiskin & Griffin (2008), p. 51.

- Lavedan (1947).

- Padovan (2002).

- Ketchum (1920).

- Pellegrino (2002).

- Yoshimura (1955).

- Schwarz (1890).

- Washburn (1984).

- Jakway (1922).

- Smith (2014).

- Bolton, Nicol & Macleod (1977).

- Bardell (2016).

- Diacu & Holmes (1999).

- Høyrup (2008). Although "many of the early Egyptologists" believed that the Egyptians used an inexact formula for the area, half the product of the base and side, Vasily Vasilievich Struve championed the view that they used the correct formula, half the product of the base and height (Clagett 1989). This question rests on the translation of one of the words in the Rhind papyrus, and with this word translated as height (or more precisely as the ratio of height to base) the formula is correct (Gunn & Peet 1929, pp. 173–174).

- Heath (1956), p. 251.

- Venema (2006), p. 89.

- Wilson (2008).

- Ball & Coxeter (1987).

- Specht et al. (2015).

References

- Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger B. (2009), When less is more: Visualizing basic inequalities, The Dolciani Mathematical Expositions, vol. 36, Mathematical Association of America, Washington, DC, ISBN 978-0-88385-342-9, MR 2498836

- Arslanagić, Šefket, "Problem η44", Inequalities proposed in Crux Mathematicorum (PDF), p. 151

- Ball, W. W. Rouse; Coxeter, H. S. M. (1987) [1892], Mathematical Recreations and Essays (13th ed.), Dover, footnote, p. 77, ISBN 0-486-25357-0

- Baloglou, George; Helfgott, Michel (2008), "Angles, area, and perimeter caught in a cubic" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 8: 13–25, MR 2373294

- Bardell, Nicholas S. (2016), "Cubic polynomials with real or complex coefficients: The full picture" (PDF), Australian Senior Mathematics Journal, 30 (2): 5–26

- Barnes, John (2012), Gems of Geometry (2nd, illustrated ed.), Springer, p. 27, ISBN 9783642309649

- Bezdek, András; Bisztriczky, Ted (2015), "Finding equal-diameter triangulations in polygons", Beiträge zur Algebra und Geometrie, 56 (2): 541–549, doi:10.1007/s13366-014-0206-6, MR 3391189, S2CID 123507725

- Bolton, Nicholas J; Nicol, D.; Macleod, G. (March 1977), "The geometry of the Śrī-yantra", Religion, 7 (1): 66–85, doi:10.1016/0048-721x(77)90008-2

- Clagett, Marshall (1989), Ancient Egyptian Science: Ancient Egyptian mathematics, American Philosophical Society, Footnote 68, pp. 195–197, ISBN 9780871692320

- Conway, J.H.; Guy, R.K. (1996), "Calabi's Triangle", The Book of Numbers, New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 206

- Conway, John; Ryba, Alex (July 2014), "The Steiner–Lehmus angle-bisector theorem", The Mathematical Gazette, 98 (542): 193–203, doi:10.1017/s0025557200001236, S2CID 124753764

- Diacu, Florin; Holmes, Philip (1999), Celestial Encounters: The Origins of Chaos and Stability, Princeton Science Library, Princeton University Press, p. 122, ISBN 9780691005454

- Gandz, Solomon (1940), "Studies in Babylonian mathematics. III. Isoperimetric problems and the origin of the quadratic equations", Isis, 32: 101–115 (1947), doi:10.1086/347645, MR 0017683, S2CID 120267556. See in particular p. 111.

- Gilbert, G.; MacDonnell, D. (1963), "The Steiner–Lehmus Theorem", Classroom Notes, American Mathematical Monthly, 70 (1): 79–80, doi:10.2307/2312796, JSTOR 2312796, MR 1531983

- Gottschau, Marinus; Haverkort, Herman; Matzke, Kilian (2018), "Reptilings and space-filling curves for acute triangles", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 60 (1): 170–199, arXiv:1603.01382, doi:10.1007/s00454-017-9953-0, S2CID 14477196

- Guinand, Andrew P. (1984), "Euler lines, tritangent centers, and their triangles", American Mathematical Monthly, 91 (5): 290–300, doi:10.2307/2322671, JSTOR 2322671, MR 0740243

- Gunn, Battiscombe; Peet, T. Eric (May 1929), "Four geometrical problems from the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 15 (1): 167–185, doi:10.1177/030751332901500130, JSTOR 3854111, S2CID 192278129

- Hadamard, Jacques (2008), Lessons in Geometry: Plane geometry, translated by Saul, Mark, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 9780821843673

- Harris, John W.; Stöcker, Horst (1998), Handbook of mathematics and computational science, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5317-4, ISBN 0-387-94746-9, MR 1621531

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956) [1925], The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements, vol. 1 (2nd ed.), New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60088-2

- Høyrup, Jens (2008), "Geometry in Mesopotamia and Egypt", Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Springer Netherlands, pp. 1019–1023, Bibcode:2008ehst.book.....S, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8619

- Ionin, Yury J. (2009), "Isosceles sets", Electronic Journal of Combinatorics, 16 (1): R141:1–R141:24, doi:10.37236/230, MR 2577309

- Jacobs, Harold R. (1974), Geometry, W. H. Freeman and Co., ISBN 0-7167-0456-0

- Jakway, Bernard C. (1922), The Principles of Interior Decoration, Macmillan, p. 48

- Kahan, W. (September 4, 2014), "Miscalculating Area and Angles of a Needle-like Triangle" (PDF), Lecture Notes for Introductory Numerical Analysis Classes, University of California, Berkeley

- Ketchum, Milo Smith (1920), The Design of Highway Bridges of Steel, Timber and Concrete, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 107

- Langley, E. M. (1922), "Problem 644", The Mathematical Gazette, 11: 173

- Lardner, Dionysius (1840), A Treatise on Geometry and Its Application in the Arts, The Cabinet Cyclopædia, London

- Lavedan, Pierre (1947), French Architecture, Penguin Books, p. 44

- Loeb, Arthur (1992), Concepts and Images: Visual Mathematics, Boston: Birkhäuser Boston, p. 180, ISBN 0-8176-3620-X

- Lord, N. J. (June 1982), "66.16 Isosceles subdivisions of triangles", The Mathematical Gazette, 66 (436): 136–137, doi:10.2307/3617750, JSTOR 3617750, S2CID 125411311

- Montroll, John (2009), Origami Polyhedra Design, A K Peters, p. 6, ISBN 9781439871065

- Oxman, Victor (2005), "On the existence of triangles with given lengths of one side, the opposite and one adjacent angle bisectors" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 5: 21–22, MR 2141652

- Padovan, Richard (2002), Towards Universality: Le Corbusier, Mies, and De Stijl, Psychology Press, p. 128, ISBN 9780415259620

- Pellegrino, S. (2002), Deployable Structures, CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences, vol. 412, Springer, pp. 99–100, ISBN 9783211836859

- Posamentier, Alfred S.; Lehmann, Ingmar (2012), The Secrets of Triangles: A Mathematical Journey, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, p. 387, ISBN 978-1-61614-587-3, MR 2963520

- Robbins, David P. (1995), "Areas of polygons inscribed in a circle", American Mathematical Monthly, 102 (6): 523–530, doi:10.2307/2974766, JSTOR 2974766, MR 1336638

- Salvadori, Mario; Wright, Joseph P. (1998), Math Games for Middle School: Challenges and Skill-Builders for Students at Every Level, Chicago Review Press, pp. 70–71, ISBN 9781569767276

- Schwarz, H. A. (1890), Gesammelte Mathematische Abhandlungen von H. A. Schwarz, Verlag von Julius Springer, pp. 309–311

- Smith, Whitney (June 26, 2014), "Flag of Saint Lucia", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 2018-09-12

- Specht, Edward John; Jones, Harold Trainer; Calkins, Keith G.; Rhoads, Donald H. (2015), Euclidean geometry and its subgeometries, Springer, Cham, p. 64, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-23775-6, ISBN 978-3-319-23774-9, MR 3445044

- Stahl, Saul (2003), Geometry from Euclid to Knots, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-032927-4

- Usiskin, Zalman; Griffin, Jennifer (2008), The Classification of Quadrilaterals: A Study in Definition, Research in Mathematics Education, Information Age Publishing, ISBN 9781607526001

- Venema, Gerard A. (2006), Foundations of Geometry, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-143700-3

- Washburn, Dorothy K. (July 1984), "A study of the red on cream and cream on red designs on Early Neolithic ceramics from Nea Nikomedeia", American Journal of Archaeology, 88 (3): 305–324, doi:10.2307/504554, JSTOR 504554, S2CID 191374019

- Wickelgren, Wayne A. (2012), How to Solve Mathematical Problems, Dover Books on Mathematics, Courier Corporation, pp. 222–224, ISBN 9780486152684.

- Wilson, Robin (2008), Lewis Carroll in Numberland: His fantastical mathematical logical life, an agony in eight fits, Penguin Books, pp. 169–170, ISBN 978-0-14-101610-8, MR 2455534

- Yoshimura, Yoshimaru (July 1955), On the mechanism of buckling of a circular cylindrical shell under axial compression, Technical Memorandum 1390, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

- Young, Cynthia Y. (2011), Trigonometry, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9780470648025

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Isosceles triangle", MathWorld

.svg.png.webp)