JPMorgan Chase

JPMorgan Chase & Co. is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered in New York City and incorporated in Delaware.[3] As of 2022, JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the United States, the world's largest bank by market capitalization, and the fifth largest bank in the world in terms of total assets, with total assets of US$3.954 trillion.[4] Additionally, JPMorgan Chase is ranked 24th on the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue. It is considered a systemically important bank by the Financial Stability Board.

| |

| Type | Public |

|---|---|

| ISIN | US46625H1005 |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Predecessors | The Bank of the Manhattan Company (since 1799) Chemical Bank (since 1824) J.P. Morgan & Co. (since 1871) Chase National Bank (since 1877) |

| Founded | December 1, 2000 |

| Founders | Aaron Burr (The Bank of the Manhattan Company) Balthazar P. Melick (Chemical Bank) John Pierpont Morgan (J.P. Morgan & Co.) John Thompson (Chase National Bank) |

| Headquarters | 383 Madison Avenue, , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jamie Dimon (Chairman & CEO) Daniel E. Pinto (President & COO) |

| Products |

|

| Revenue | |

| AUM | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | |

| Divisions | Asset and Wealth Management, Consumer and Community Banking, Commercial Banking, Corporate and Investment Banking |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Capital ratio | Tier 1 15.0% (2021) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

As a "Bulge Bracket" bank, it is a major provider of various investment banking and financial services. It is one of America's Big Four banks, along with Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo.[5] JPMorgan Chase is considered to be a universal bank and a custodian bank. The J.P. Morgan brand is used by the investment banking, asset management, private banking, private wealth management, commercial banking, and treasury services divisions. Fiduciary activity within private banking and private wealth management is done under the aegis of JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A.—the actual trustee.

The Chase brand is used for credit card services in the United States and Canada, and the bank's retail banking activities in the United States and United Kingdom. Commercial Banking at JPMorgan Chase operates under both the Chase and J.P. Morgan brands. The bank's corporate headquarters are currently located at 383 Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, since the prior headquarters building directly across the street, 270 Park Avenue, was demolished and a larger replacement headquarters is being built on the same site.[6]

The current company was originally known as Chemical Bank, which acquired Chase Manhattan and assumed that company's name. The present company was formed in 2000, when Chase Manhattan Corporation merged with J.P. Morgan & Co.[6]

History

JPMorgan Chase, in its current structure, is the result of the combination of several large U.S. banking companies since 1996, including Chase Manhattan Bank, J.P. Morgan & Co., Bank One, Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual. Going back further, its predecessors include major banking firms among which are Chemical Bank, Manufacturers Hanover, First Chicago Bank, National Bank of Detroit, Texas Commerce Bank, Providian Financial and Great Western Bank. The company's oldest predecessor institution, The Bank of the Manhattan Company, was the third oldest banking corporation in the United States, and the 31st oldest bank in the world, having been established on September 1, 1799, by Aaron Burr.[8]

The Chase Manhattan Bank was formed upon the 1955 purchase of Chase National Bank (established in 1877) by The Bank of the Manhattan Company (established in 1799),[9] the company's oldest predecessor institution. The Bank of the Manhattan Company was the creation of Aaron Burr, who transformed the company from a water carrier into a bank.[10]

According to page 115 of An Empire of Wealth by John Steele Gordon, the origin of this strand of JPMorgan Chase's history runs as follows:

At the turn of the nineteenth century, obtaining a bank charter required an act of the state legislature. This of course injected a powerful element of politics into the process and invited what today would be called corruption but then was regarded as business as usual. Hamilton's political enemy—and eventual murderer—Aaron Burr was able to create a bank by sneaking a clause into a charter for a company, called The Manhattan Company, to provide clean water to New York City. The innocuous-looking clause allowed the company to invest surplus capital in any lawful enterprise. Within six months of the company's creation, and long before it had laid a single section of water pipe, the company opened a bank, the Bank of the Manhattan Company. Still in existence, it is today JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States.

Led by David Rockefeller during the 1970s and 1980s, Chase Manhattan emerged as one of the largest and most prestigious banking concerns, with leadership positions in syndicated lending, treasury and securities services, credit cards, mortgages, and retail financial services. Weakened by the real estate collapse in the early 1990s, it was acquired by Chemical Bank in 1996, retaining the Chase name.[11][12] Before its merger with J.P. Morgan & Co., the new Chase expanded the investment and asset management groups through two acquisitions. In 1999, it acquired San Francisco-based Hambrecht & Quist for $1.35 billion.[13] In April 2000, UK-based Robert Fleming & Co. was purchased by the new Chase Manhattan Bank for $7.7 billion.[14]

Chemical Banking Corporation

The New York Chemical Manufacturing Company was founded in 1823 as a maker of various chemicals. In 1824, the company amended its charter to perform banking activities and created the Chemical Bank of New York. After 1851, the bank was separated from its parent and grew organically and through a series of mergers, most notably with Corn Exchange Bank in 1954, Texas Commerce Bank (a large bank in Texas) in 1986, and Manufacturer's Hanover Trust Company in 1991 (the first major bank merger "among equals"). In the 1980s and early 1990s, Chemical emerged as one of the leaders in the financing of leveraged buyout transactions. In 1984, Chemical launched Chemical Venture Partners to invest in private equity transactions alongside various financial sponsors. By the late 1980s, Chemical developed its reputation for financing buyouts, building a syndicated leveraged finance business and related advisory businesses under the auspices of the pioneering investment banker, Jimmy Lee.[15][16] At many points throughout this history, Chemical Bank was the largest bank in the United States (either in terms of assets or deposit market share).

In 1996, Chemical Bank acquired Chase Manhattan. Although Chemical was the nominal survivor, it took the better-known Chase name.[11][12] To this day, JPMorgan Chase retains Chemical's pre-1996 stock price history, as well as Chemical's former headquarters site at 270 Park Avenue (the current building was demolished and a larger replacement headquarters is being built on the same site).

J.P. Morgan & Company

The House of Morgan was born out of the partnership of Drexel, Morgan & Co., which in 1895 was renamed J.P. Morgan & Co. (see also: J. Pierpont Morgan).[17] J.P. Morgan & Co. financed the formation of the United States Steel Corporation, which took over the business of Andrew Carnegie and others and was the world's first billion dollar corporation.[18] In 1895, J.P. Morgan & Co. supplied the United States government with $62 million in gold to float a bond issue and restore the treasury surplus of $100 million.[19] In 1892, the company began to finance the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and led it through a series of acquisitions that made it the dominant railroad transporter in New England.[20]

Built in 1914, 23 Wall Street was the bank's headquarters for decades. On September 16, 1920, a terrorist bomb exploded in front of the bank, injuring 400 and killing 38.[21] Shortly before the bomb went off, a warning note was placed in a mailbox at the corner of Cedar Street and Broadway. The case has never been solved, and was rendered inactive by the FBI in 1940.[22]

In August 1914, Henry P. Davison, a Morgan partner, made a deal with the Bank of England to make J.P. Morgan & Co. the monopoly underwriter of war bonds for the UK and France. The Bank of England became a "fiscal agent" of J.P. Morgan & Co., and vice versa.[23] The company also invested in the suppliers of war equipment to Britain and France. The company profited from the financing and purchasing activities of the two European governments.[23] Since the U.S. federal government withdrew from world affairs under successive isolationist Republican administrations in the 1920s, J.P. Morgan & Co. continued playing a major role in global affairs since most European countries still owed war debts.[24]

In the 1930s, J.P. Morgan & Co. and all integrated banking businesses in the United States were required by the provisions of the Glass–Steagall Act to separate their investment banking from their commercial banking operations. J.P. Morgan & Co. chose to operate as a commercial bank.

In 1935, after being barred from the securities business for over a year, the heads of J.P. Morgan spun off its investment-banking operations. Led by J.P. Morgan partners, Henry S. Morgan (son of Jack Morgan and grandson of J. Pierpont Morgan) and Harold Stanley, Morgan Stanley was founded on September 16, 1935, with $6.6 million of nonvoting preferred stock from J.P. Morgan partners. In order to bolster its position, in 1959, J.P. Morgan merged with the Guaranty Trust Company of New York to form the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company.[17] The bank would continue to operate as Morgan Guaranty Trust until the 1980s, before migrating back to the use of the J.P. Morgan brand. In 1984, the group purchased the Purdue National Corporation of Lafayette, Indiana. In 1988, the company once again began operating exclusively as J.P. Morgan & Co.[25]

Bank One Corporation

In 2004, JPMorgan Chase merged with Chicago-based Bank One Corp., bringing on board current chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon as president and COO.[26] He succeeded former CEO William B. Harrison, Jr.[27] Dimon introduced new cost-cutting strategies, and replaced former JPMorgan Chase executives in key positions with Bank One executives—many of whom were with Dimon at Citigroup. Dimon became CEO in December 2005 and chairman in December 2006.[28]

Bank One Corporation was formed with the 1998 merger of Banc One of Columbus, Ohio and First Chicago NBD.[29] This merger was considered a failure until Dimon took over and reformed the new firm's practices. Dimon effected changes to make Bank One Corporation a viable merger partner for JPMorgan Chase.[30]

Bank One Corporation, formerly First Bancgroup of Ohio, was founded as a holding company for City National Bank of Columbus, Ohio, and several other banks in that state, all of which were renamed "Bank One" when the holding company was renamed Banc One Corporation.[31] With the beginning of interstate banking they spread into other states, always renaming acquired banks "Bank One." After the First Chicago NBD merger, adverse financial results led to the departure of CEO John B. McCoy, whose father and grandfather had headed Banc One and predecessors. JPMorgan Chase completed the acquisition of Bank One in the third quarter of 2004.[31]

Bear Stearns

At the end of 2007, Bear Stearns was the fifth largest investment bank in the United States but its market capitalization had deteriorated through the second half of the year.[32] On Friday, March 14, 2008, Bear Stearns lost 47% of its equity market value as rumors emerged that clients were withdrawing capital from the bank. Over the following weekend, it emerged that Bear Stearns might prove insolvent, and on March 15, 2008, the Federal Reserve engineered a deal to prevent a wider systemic crisis from the collapse of Bear Stearns.[33]

On March 16, 2008, after a weekend of intense negotiations between JPMorgan, Bear, and the federal government, JPMorgan Chase announced its plans to acquire Bear Stearns in a stock swap worth $2.00 per share or $240 million pending shareholder approval scheduled within 90 days.[33] In the interim, JPMorgan Chase agreed to guarantee all Bear Stearns trades and business process flows.[34] On March 18, 2008, JPMorgan Chase formally announced the acquisition of Bear Stearns for $236 million.[32] The stock swap agreement was signed that night.[35]

On March 24, 2008, after public discontent over the low acquisition price threatened the deal's closure, a revised offer was announced at approximately $10 per share.[32] Under the revised terms, JPMorgan also immediately acquired a 39.5% stake in Bear Stearns using newly issued shares at the new offer price and gained a commitment from the board, representing another 10% of the share capital, that its members would vote in favor of the new deal. With sufficient commitments to ensure a successful shareholder vote, the merger was completed on May 30, 2008.[36]

Washington Mutual

On September 25, 2008, JPMorgan Chase bought most of the banking operations of Washington Mutual from the receivership of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. That night, the Office of Thrift Supervision, in what was by far the largest bank failure in American history, had seized Washington Mutual Bank and placed it into receivership. The FDIC sold the bank's assets, secured debt obligations, and deposits to JPMorgan Chase & Co for $1.836 billion, which re-opened the bank the following day. As a result of the takeover, Washington Mutual shareholders lost all their equity.[37]

JPMorgan Chase raised $10 billion in a stock sale to cover writedowns and losses after taking on deposits and branches of Washington Mutual.[38] Through the acquisition, JPMorgan now owns the former accounts of Providian Financial, a credit card issuer WaMu acquired in 2005. The company announced plans to complete the rebranding of Washington Mutual branches to Chase by late 2009.

Chief executive Alan H. Fishman received a $7.5 million sign-on bonus and cash severance of $11.6 million after being CEO for 17 days.[39]

Lawsuits and legal settlements

Chase paid out over $2 billion in fines and legal settlements for their role in financing Enron Corporation with aiding and abetting Enron Corp.'s securities fraud, which collapsed amid a financial scandal in 2001.[40] In 2003, Chase paid $160 million in fines and penalties to settle claims by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Manhattan district attorney's office. In 2005, Chase paid $2.2 billion to settle a lawsuit filed by investors in Enron.[41]

In December 2002, Chase paid fines totaling $80 million, with the amount split between the states and the federal government. The fines were part of a settlement involving charges that ten banks, including Chase, deceived investors with biased research. The total settlement with the ten banks was $1.4 billion. The settlement required that the banks separate investment banking from research, and ban any allocation of IPO shares.[42]

JPMorgan Chase, which helped underwrite $15.4 billion of WorldCom's bonds, agreed in March 2005 to pay $2 billion; that was 46 percent, or $630 million, more than it would have paid had it accepted an investor offer in May 2004 of $1.37 billion. J.P. Morgan was the last big lender to settle. Its payment is the second largest in the case, exceeded only by the $2.6 billion accord reached in 2004 by Citigroup.[43] In March 2005, 16 of WorldCom's 17 former underwriters reached settlements with the investors.[44][45]

In 2008 and 2009, 14 lawsuits were filed against JPMorgan Chase in various district courts on behalf of Chase credit card holders claiming the bank violated the Truth in Lending Act, breached its contract with the consumers, and committed a breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The consumers contended that Chase, with little or no notice, increased minimum monthly payments from 2% to 5% on loan balances that were transferred to consumers' credit cards based on the promise of a fixed interest rate. In May 2011, the United States District Court for the Northern District of California certified the class action lawsuit. On July 23, 2012, Chase agreed to pay $100 million to settle the claim.[46]

In November 2009, a week after Birmingham, Alabama Mayor Larry Langford was convicted for financial crimes related to bond swaps for Jefferson County, Alabama, JPMorgan Chase & Co. agreed to a $722 million settlement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to end a probe into the sales of derivatives that allegedly contributed to the near-bankruptcy of the county. JPMorgan had been chosen by the county commissioners to refinance the county's sewer debt, and the SEC had alleged that JPMorgan made undisclosed payments to close friends of the commissioners in exchange for the deal and made up for the costs by charging higher interest rates on the swaps.[47]

In June 2010, J.P. Morgan Securities was fined a record £33.32 million ($49.12 million) by the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA) for failing to protect an average of £5.5 billion of clients' money from 2002 to 2009.[48][49] FSA requires financial firms to keep clients' funds in separate accounts to protect the clients in case such a firm becomes insolvent. The firm had failed to properly segregate client funds from corporate funds following the merger of Chase and J.P. Morgan, resulting in a violation of FSA regulations but no losses to clients. The clients' funds would have been at risk had the firm become insolvent during this period.[50] J.P. Morgan Securities reported the incident to the FSA, corrected the errors, and cooperated in the ensuing investigation, resulting in the fine being reduced 30% from an original amount of £47.6 million.[49]

In January 2011, JPMorgan Chase admitted that it wrongly overcharged several thousand military families for their mortgages, including active-duty personnel in the War in Afghanistan. The bank also admitted it improperly foreclosed on more than a dozen military families; both actions were in clear violation of the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act which automatically lowers mortgage rates to 6 percent, and bars foreclosure proceedings of active-duty personnel. The overcharges may have never come to light were it not for legal action taken by Captain Jonathan Rowles. Both Captain Rowles and his spouse Julia accused Chase of violating the law and harassing the couple for nonpayment. An official stated that the situation was "grim" and Chase initially stated it would be refunding up to $2,000,000 to those who were overcharged, and that families improperly foreclosed on have gotten or will get their homes back.[51] Chase has acknowledged that as many as 6,000 active duty military personnel were illegally overcharged, and more than 18 military families homes were wrongly foreclosed. In April, Chase agreed to pay a total of $27 million in compensation to settle the class-action suit.[52] At the company's 2011 shareholders' meeting, Dimon apologized for the error and said the bank would forgive the loans of any active-duty personnel whose property had been foreclosed. In June 2011, lending chief Dave Lowman was forced out over the scandal.[53][54]

On August 25, 2011, JPMorgan Chase agreed to settle fines with regard to violations of the sanctions under the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) regime. The U.S. Department of Treasury released the following civil penalties information under the heading: "JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A. Settles Apparent Violations of Multiple Sanctions Programs":

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A, New York, NY ("JPMC") has agreed to remit $88,300,000 to settle a potential civil liability for apparent violations of the Cuban Assets Control Regulations ("CACR"), 31 C.F.R. part 515; the Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferators Sanctions Regulations ("WMDPSR"), 31 C.F.R. part 544; Executive Order 13382, "Blocking Property of Weapons of Mass Destruction Proliferators and Their Supporters;" the Global Terrorism Sanctions Regulations ("GTSR"), 31 C.F.R. part 594; the Iranian Transactions Regulations ("ITR"), 31 C.F.R. part 560; the Sudanese Sanctions Regulations ("SSR"), 31 C.F.R. part 538; the Former Liberian Regime of Charles Taylor Sanctions Regulations ("FLRCTSR"), 31 C.F.R. part 593; and the Reporting, Procedures, and Penalties Regulations ("RPPR"), 31 C.F.R. part 501, that occurred between December 15, 2005, and March 1, 2011.

— U.S. Department of the Treasury Resource Center, OFAC Recent Actions. Retrieved June 18, 2013.[55]

On February 9, 2012, it was announced that the five largest mortgage servicers (Ally/GMAC, Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo) agreed to a historic settlement with the federal government and 49 states.[56] The settlement, known as the National Mortgage Settlement (NMS), required the servicers to provide about $26 billion in relief to distressed homeowners and in direct payments to the states and federal government. This settlement amount makes the NMS the second largest civil settlement in U.S. history, only trailing the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.[57] The five banks were also required to comply with 305 new mortgage servicing standards. Oklahoma held out and agreed to settle with the banks separately.

In 2012, JPMorgan Chase & Co was charged for misrepresenting and failing to disclose that the CIO had engaged in extremely risky and speculative trades that exposed JPMorgan to significant losses.[58]

In July 2013, The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approved a stipulation and consent agreement under which JPMorgan Ventures Energy Corporation (JPMVEC), a subsidiary of JPMorgan Chase & Co., agreed to pay $410 million in penalties and disgorgement to ratepayers for allegations of market manipulation stemming from the company's bidding activities in electricity markets in California and the Midwest from September 2010 through November 2012. JPMVEC agreed to pay a civil penalty of $285 million to the U.S. Treasury and to disgorge $125 million in unjust profits. JPMVEC admitted the facts set forth in the agreement, but neither admitted nor denied the violations.[59] The case stemmed from multiple referrals to FERC from market monitors in 2011 and 2012 regarding JPMVEC's bidding practices. FERC investigators determined that JPMVEC engaged in 12 manipulative bidding strategies designed to make profits from power plants that were usually out of the money in the marketplace. In each of them, the company made bids designed to create artificial conditions that forced California and Midcontinent Independent System Operators (ISOs) to pay JPMVEC outside the market at premium rates.[59] FERC investigators further determined that JPMVEC knew that the California ISO and Midcontinent ISO received no benefit from making inflated payments to the company, thereby defrauding the ISOs by obtaining payments for benefits that the company did not deliver beyond the routine provision of energy. FERC investigators also determined that JPMVEC's bids displaced other generation and altered day ahead and real-time prices from the prices that would have resulted had the company not submitted the bids.[59] Under the Energy Policy Act of 2005, Congress directed FERC to detect, prevent, and appropriately sanction the gaming of energy markets. According to FERC, the Commission approved the settlement as in the public interest.[59]

FERC's investigation of energy market manipulations led to a subsequent investigation into possible obstruction of justice by employees of JPMorgan Chase.[60] Various newspapers reported in September 2013 that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and US Attorney's Office in Manhattan were investigating whether employees withheld information or made false statements during the FERC investigation.[60] The reported impetus for the investigation was a letter from Massachusetts Senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey, in which they asked FERC why no action was taken against people who impeded the FERC investigation.[60] At the time of the FBI investigation, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations was also looking into whether JPMorgan Chase employees impeded the FERC investigation.[60] Reuters reported that JPMorgan Chase was facing over a dozen investigations at the time.[60]

In August 2013, JPMorgan Chase announced that it was being investigated by the United States Department of Justice over its offerings of mortgage-backed securities leading up to the financial crisis of 2007–08. The company said that the Department of Justice had preliminarily concluded that the firm violated federal securities laws in offerings of subprime and Alt-A residential mortgage securities during the period 2005 to 2007.[61] On November 19, 2013, the Justice Department announced that JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay $13 billion to settle investigations into its business practices pertaining to mortgage-backed securities.[62] Of that amount, $9 billion was penalties and fines, and the remaining $4 billion was consumer relief. This was the largest corporate settlement to date. Conduct at Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual prior to their 2008 acquisitions accounted for much of the alleged wrongdoing. The agreement did not settle criminal charges.[63]

In November 2016, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay $264 million in fines to settle civil and criminal charges involving a systematic bribery scheme spanning 2006 to 2013 in which the bank secured business deals in Hong Kong by agreeing to hire hundreds of friends and relatives of Chinese government officials, resulting in more than $100 million in revenue for the bank.[64]

In January 2017, the United States sued the company, accusing it of discriminating against "thousands" of black and Hispanic mortgage borrowers between 2006 and at least 2009.[65][66]

On December 26, 2018, as part of an investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) into abusive practices related to American depositary receipts (ADRs), JPMorgan agreed to pay more than $135 million to settle charges of improper handling of "pre-released" ADRs without admitting or denying the SEC's findings. The sum consisted of $71 million in ill-gotten gains plus $14.4 million in prejudgment interest and an additional penalty of $49.7 million.[67]

Madoff fraud

Bernie Madoff opened a business account at Chemical Bank in 1986 and maintained it until 2008, long after Chemical acquired Chase.

In 2010, Irving Picard, the SIPC receiver appointed to liquidate Madoff's company, alleged that JPMorgan Chase failed to prevent Madoff from defrauding his customers. According to the suit, Chase "knew or should have known" that Madoff's wealth management business was a fraud. However, Chase did not report its concerns to regulators or law enforcement until October 2008, when it notified the UK Serious Organised Crime Agency. Picard argued that even after Morgan's investment bankers reported its concerns about Madoff's performance to UK officials, Chase's retail banking division did not put any restrictions on Madoff's banking activities until his arrest two months later.[68] The receiver's suit against JPMorgan Chase was dismissed by the Court for failing to set forth any legally cognizable claim for damages.[69]

In the fall of 2013, JPMorgan Chase began talks with prosecutors and regulators regarding compliance with anti-money-laundering and know-your-customer banking regulations in connection with Madoff.

On January 7, 2014, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay a total of $2.05 billion in fines and penalties to settle civil and criminal charges related to its role in the Madoff scandal. The government filed a two-count criminal information charging JPMorgan Chase with Bank Secrecy Act violations, but the charges would be dismissed within two years provided that JPMorgan Chase reforms its anti-money laundering procedures and cooperates with the government in its investigation. The bank agreed to forfeit $1.7 billion.

The lawsuit, which was filed on behalf of shareholders against Chief Executive Jamie Dimon and other high-ranking JPMorgan Chase employees, used statements made by Bernie Madoff during interviews conducted while in prison in Butner, North Carolina claiming that JPMorgan Chase officials knew of the fraud. The lawsuit stated that "JPMorgan was uniquely positioned for 20 years to see Madoff's crimes and put a stop to them ... But faced with the prospect of shutting down Madoff's account and losing lucrative profits, JPMorgan - at its highest level - chose to turn a blind eye."[70]

JPMorgan Chase also agreed to pay a $350 million fine to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and settle the suit filed against it by Picard for $543 million.[71][72][73][74]

Other recent acquisitions

In 2006, JPMorgan Chase purchased Collegiate Funding Services, a portfolio company of private equity firm Lightyear Capital, for $663 million. CFS was used as the foundation for the Chase Student Loans, previously known as Chase Education Finance.[75]

In April 2006, JPMorgan Chase acquired Bank of New York Mellon's retail and small business banking network. The acquisition gave Chase access to 339 additional branches in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.[76] In 2008, J.P. Morgan acquired the UK-based carbon offsetting company ClimateCare.[77] In November 2009, J.P. Morgan announced it would acquire the balance of J.P. Morgan Cazenove, an advisory and underwriting joint venture established in 2004 with the Cazenove Group.[78] In 2013, J.P. Morgan acquired Bloomspot, a San Francisco-based startup. Shortly after the acquisition, the service was shut down and Bloomspot's talent was left unused.[79][80] In 2021, the company made more than over 30 acquisitions including OpenInvest and Nutmeg.[81][82] In March 2022, JPMorgan Chase announced that would acquire Global Shares, a cloud-based provider of share plan software management.[83][84]

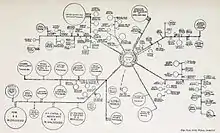

Acquisition history

The following is an illustration of the company's major mergers and acquisitions and historical predecessors, although this is not a comprehensive list:

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recent history

In 2013, after teaming up with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline and Children's Investment Fund, JPMorgan Chase, Under Jamie Dimon launched a $94 Million fund with a focus on "late-stage healthcare technology trials". The "$94 million Global Health Investment Fund will give money to a final-stage drug, vaccine, and medical device studies that are otherwise stalled at companies because of their relatively high failure risk and low consumer demand. Examples of problems that could be addressed by the fund include malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and maternal and infant mortality, according to the Gates and JPMorgan Chase led-group"[94]

The 2014 JPMorgan Chase data breach, disclosed in September 2014, compromised the JPMorgan Chase accounts of over 83 million customers. The attack was discovered by the bank's security team in late July 2014, but not completely halted until the middle of August.[95][96]

In October 2014, J.P. Morgan sold its commodities trader unit to Mercuria for $800 million, a quarter of the initial valuation of $3.5 billion, as the transaction excluded some oil and metal stockpiles and other assets.[97]

In March 2016, J.P. Morgan decided not to finance coal mines and coal power plants in wealthy countries.[98]

In December 2016, 14 former executives of the Wendel investment company faced trial for tax fraud while JPMorgan Chase was to be pursued for complicity. Jean-Bernard Lafonta was convicted December 2015 for spreading false information and insider trading, and fined 1.5 million euros.[99]

In March 2017, Lawrence Obracanik, a former JPMorgan Chase & Co. employee, pleaded guilty to criminal charges that he stole more than $5 million from his employer to pay personal debts.[100] In June 2017, Matt Zames, the now-former COO of the bank decided to leave the firm.[101] In December 2017, J.P. Morgan was sued by the Nigerian government for $875 million, which Nigeria alleges was transferred by J.P. Morgan to a corrupt former minister.[102] Nigeria accused J.P. Morgan of being "grossly negligent".[103]

In February 2019, J.P. Morgan announced the launch of JPM Coin, a digital token that will be used to settle transactions between clients of its wholesale payments business.[104] It would be the first cryptocurrency issued by a United States bank.[105]

On May 14, 2020, Financial Times, citing a report which revealed how companies are treating employees, their supply chains and other stakeholders, during the COVID-19 pandemic, documented that J.P. Morgan Asset Management alongside Fidelity Investments and Vanguard have been accused of paying lip services to cover human rights violations. The UK based media also referenced that a few of the world's biggest fund houses took the action in order to lessen the impact of abuses, such as modern slavery, at the companies they invest in. However, J.P. Morgan replying to the report said that it took "human rights violations very seriously" and "any company with alleged or proven violations of principles, including human rights abuses, is scrutinised and may result in either enhanced engagement or removal from a portfolio."[106]

In September 2020, the company admitted that it manipulated precious metals futures and government bond markets in a span period of eight years. It settled with the United States Department of Justice, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission for $920 million. J.P. Morgan will not face criminal charges, however, it will launch into a deferred prosecution agreement for three years.[107]

In 2021, J.P. Morgan funded the failed attempt to create a European Super League in European soccer, which, if successful, would have ended the meritocratic European pyramid soccer system. J.P. Morgan's role in the creation of the Super League was instrumental; the investment bank was reported to have worked on it for several years.[108] After a strong backlash, the owners/management of the teams that proposed creating the league pulled out of it.[109] After the attempt to end the European football hierarchy failed, J.P. Morgan apologized for its role in the scheme.[108] JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said the company "kind of missed" that football supporters would respond negatively to the Super League.[110]

In September 2021, JPMorgan Chase entered the UK retail banking market by launched an app-based current account under the Chase brand. This is the company's first retail banking operation outside the of United States.[111][112][113]

In March 2022, JPMorgan Chase announced to wind down its business in Russia in compliance with regulatory and licensing requirements.[114]

On May 20, 2022, JPMorgan Chase used blockchain for collateral settlements, the latest Wall Street experimentation with the technology in the trading of traditional financial assets.[115]

In September 2022, the company announced it was acquiring California-based Renovite Technologies to expand its payments processing business amid heavy competition from fintech firms like Stripe and Ayden. This comes on top of previous, similar moves of buying a 49% stake in fintech Viva Wallet and a majority sake in Volkswagen's payments business, among many other acquisitions in other areas of finance.[116][117][118]

Financial data

| Year | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 25.87 | 31.15 | 33.19 | 29.34 | 29.61 | 33.19 | 42.74 | 54.25 | 62.00 | 71.37 | 67.25 | 100.4 | 102.7 | 97.23 | 97.03 | 96.61 | 94.21 | 93.54 | 95.67 | 99.62 | 109.03 | 115.40 | 119.54 |

| Net income | 4.745 | 7.501 | 5.727 | 1.694 | 1.663 | 6.719 | 4.466 | 8.483 | 14.44 | 15.37 | 5.605 | 11.73 | 17.37 | 18.98 | 21.28 | 17.92 | 21.76 | 24.44 | 24.73 | 24.44 | 32.47 | 36.43 | 29.13 |

| Assets | 626.9 | 667.0 | 715.3 | 693.6 | 758.8 | 770.9 | 1,157 | 1,199 | 1,352 | 1,562 | 2,175 | 2,032 | 2,118 | 2,266 | 2,359 | 2,416 | 2,573 | 2,352 | 2,491 | 2,534 | 2,623 | 2,687 | 3,386 |

| Equity | 35.10 | 35.06 | 42.34 | 41.10 | 42.31 | 46.15 | 105.7 | 107.2 | 115.8 | 123.2 | 166.9 | 165.4 | 176.1 | 183.6 | 204.1 | 210.9 | 231.7 | 247.6 | 254.2 | 255.7 | 256.5 | 261.3 | 279.4 |

| Capitalization | 75.03 | 138.7 | 138.4 | 167.2 | 147.0 | 117.7 | 164.3 | 165.9 | 125.4 | 167.3 | 219.7 | 232.5 | 241.9 | 307.3 | 366.3 | 319.8 | 429.9 | 387.5 | |||||

| Headcount (in thousands) | 96.37 | 161.0 | 168.8 | 174.4 | 180.7 | 225.0 | 222.3 | 239.8 | 260.2 | 259.0 | 251.2 | 241.4 | 234.6 | 243.4 | 252.5 | 256.1 | 257.0 | 255.4 |

Note. For years 1998, 1999, and 2000 figures are combined for The Chase Manhattan Corporation and J.P.Morgan & Co. Incorporated as if a merger between them already happened.

JPMorgan Chase[127] was the biggest bank at the end of 2008 as an individual bank (not including subsidiaries). As of 2022, JPMorgan Chase is ranked 24 on the Fortune 500 rankings of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[128]

CEO-to-worker pay ratio

For the first time in 2018, a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule mandated under the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act requires publicly traded companies to disclose how their CEOs are compensated in comparison with their employees. In public filings, companies have to disclose their pay ratios, or the CEO's compensation divided by the median employee's.[129]

2017

According to SEC filings, JPMorgan Chase & Co. paid its CEO $28,320,175 in 2017, while the average worker employed by JPMorgan Chase & Co. was paid $77,799 in 2017, marking a CEO-to-worker pay ratio of 364 to 1.[130] As of April 2018, steelmaker Nucor represented the median CEO-to-worker pay ratio from SEC filings with values of 133 to 1.[131] On May 2, 2013, Bloomberg BusinessWeek found the ratio of CEO pay to the typical worker rose from about 20-to-1 in the 1950s to 120-to-1 in 2000.[132]

2018

Total 2018 compensation for CEO Jamie Dimon was $30,040,153, and total compensation of the median employee was determined to be $78,923; the resulting pay ratio was estimated to be 381 to 1.[133]

Structure

JPMorgan Chase & Co. owns two key subsidiaries in the United States:[134]

- JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A.,

- JPMorgan Securities, LLC.

For management reporting purposes, J P Morgan Chase's activities are organized into a corporate segment and 4 business segments:

- Consumer and community banking (primarily under the Chase brand),

- Corporate and investment banking (primarily under the J.P. Morgan brand),

- Commercial banking and

- Asset management (primarily under the J.P. Morgan brand).[135]

JPMorgan Europe, Ltd.

The company, known previously as Chase Manhattan International Limited, was founded on September 18, 1968.[136][137]

In August 2008, the bank announced plans to construct a new European headquarters at Canary Wharf, London.[138] These plans were subsequently suspended in December 2010, when the bank announced the purchase of a nearby existing office tower at 25 Bank Street for use as the European headquarters of its investment bank.[139] 25 Bank Street had originally been designated as the European headquarters of Enron and was subsequently used as the headquarters of Lehman Brothers International (Europe).

The regional office is in London with offices in Bournemouth, Glasgow, and Edinburgh for asset management, private banking, and investment.[140]

Divisions

JPMorgan's business consists of four main segments: Consumer and Community Banking, Corporate and Investment Banking, Commercial Banking and Asset Management.[141]

Operations

Earlier in 2011, the company announced that by the use of supercomputers, the time taken to assess risk had been greatly reduced, from arriving at a conclusion within hours to what is now minutes. The banking corporation uses for this calculation Field-Programmable Gate Array technology.[142]

History

The Bank began operations in Japan in 1924,[143] in Australia during the later part of the nineteenth century,[144] and in Indonesia during the early 1920s.[145] An office of the Equitable Eastern Banking Corporation (one of J.P. Morgan's predecessors) opened a branch in China in 1921 and Chase National Bank was established there in 1923.[146] The bank has operated in Saudi Arabia[147] and India[148] since the 1930s. Chase Manhattan Bank opened an office in South Korea in 1967.[149] The firm's presence in Greece dates to 1968.[150] An office of JPMorgan was opened in Taiwan in 1970,[151] in Russia (Soviet Union) in 1973,[152] and Nordic operations began during the same year.[153] Operations in Poland began in 1995.[150]

Political Contributions

JPMorgan Chase's PAC and its employees contributed $2.6 million to federal campaigns in 2014 and financed its lobbying team with $4.7 million in the first three quarters of 2014. JPMorgan's giving has been focused on Republicans, with 62 percent of its donations going to GOP recipients in 2014. Still, 78 House Democrats received campaign cash from JPMorgan's PAC in the 2014 cycle at an average of $5,200 and a total of 38 of the Democrats who voted for the 2015 spending bill took money from JPMorgan's PAC in 2014. JPMorgan Chase's PAC made maximum donations to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and the leadership PACs of Steny Hoyer and Jim Himes in 2014.[154]

Philanthropy

In May 2022, JPMorgan Chase announced that they had committed a five-year $20 million commitment in support of summer youth employment programs (SYEPs) across 24 cities in the United States. This commitment came as part of the organisations wider $30 billion commitment to drive inclusive economic recovery and increase opportunities for underserved communities. The latest commitment will place funds to local governments, employers, and community partners to aid in giving young people access to SYEPs and gain experience to help in building careers.[155]

Criticism

Climate change and investments in fossil fuels

JPMorgan has come under criticism for investing in new fossil fuels projects since the Paris climate change agreement. From 2016 to the first half of 2019 it provided $75 billion (£61 billion) to companies expanding in sectors such as fracking and Arctic oil and gas exploration.[156] According to Rainforest Action Network its total fossil fuel financing was $64 billion in 2018, $69 billion in 2017 and $62 billion in 2016.[157] As of 2021 it is the largest lender to the fossil fuel industry in the world.[158]

An internal study, 'Risky business: the climate and macroeconomy', by bank economists David Mackie and Jessica Murray was leaked in early‑2020. The report, dated 14 January 2020, states that under our current unsustainable trajectory of climate change "we cannot rule out catastrophic outcomes where human life as we know it is threatened". JPMorgan subsequently distanced itself from the content of the study.[159]

Slavery

In 2005, JPMorgan Chase acknowledged that its two predecessor banks had received ownership of thousands of slaves as collateral prior to the Civil War. The company apologized for contributing to the "brutal and unjust institution" of slavery. The bank paid $5 million in reparations in the form of a scholarship program for Black students.[160][161][162]

Offices

Although the old Chase Manhattan Bank's headquarters were at One Chase Manhattan Plaza (now 28 Liberty Street) in Lower Manhattan, the current temporary world headquarters for JPMorgan Chase & Co. are located at 383 Madison Avenue. In 2018, JPMorgan announced they would demolish the current headquarters building at 270 Park Avenue, which was Union Carbide's former headquarters, to make way for a newer building at 270 Park Avenue that will be 681 feet (208 m) taller than the previous building. Demolition was completed in the spring of 2021, and the new building will be completed in 2025. The replacement 1,388 feet (423 m) and 70-story headquarters will contain 2,500,000 square feet (230,000 m2), and will be able to fit 15,000 employees, whereas the current building fits 6,000 employees in a space that has a capacity of 3,500. The new headquarters is part of the East Midtown rezoning plan.[163] When construction is completed in 2025, the headquarters will then move back into the new building at 270 Park Avenue.

As the new headquarters is replaced, the bulk of North American operations take place in five nearby buildings on or near Park Avenue in New York City: the former Bear Stearns Building at 383 Madison Avenue (just south of 270 Park Avenue), the former Chemical Bank Building at 277 Park Avenue just to the east, 237 Park Avenue, and 390 Madison Avenue.

The Asia Pacific headquarters for JPMorgan is located in Hong Kong at Chater House.

Approximately 11,050 employees are located in Columbus at the McCoy Center, the former Bank One offices. The building is the largest JPMorgan Chase & Co. facility in the world and the second-largest single-tenant office building in the United States behind The Pentagon.[164]

The bank moved some of its operations to the JPMorgan Chase Tower in Houston, when it purchased Texas Commerce Bank.

JPMorgan Chase Temporary World Headquarters

JPMorgan Chase Temporary World Headquarters

383 Madison Avenue

New York City, New York Artist's impression of the under–construction new JPMorgan Chase World Headquarters

Artist's impression of the under–construction new JPMorgan Chase World Headquarters

270 Park Avenue

New York City, New York 277 Park Avenue

277 Park Avenue

New York City, New York 28 Liberty Street (Chase Manhattan's former headquarters)

28 Liberty Street (Chase Manhattan's former headquarters)

New York City, New York Chase Tower

Chase Tower

Phoenix, Arizona Chase Tower

Chase Tower

Chicago, Illinois Chase Tower

Chase Tower

Dallas, Texas JPMorgan Chase Tower

JPMorgan Chase Tower

Houston, Texas 25 Bank Street

25 Bank Street

London, United Kingdom

The Global Corporate Bank's main headquarters are in London, with regional headquarters in Hong Kong, New York and Sao Paulo.[165]

The Card Services division has its headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware, with Card Services offices in Elgin, Illinois; Springfield, Missouri; San Antonio, Texas; Mumbai, India; and Cebu, Philippines.

Additional large operation centers are located in Phoenix, Arizona; Los Angeles, California, Newark, Delaware; Orlando, Florida; Tampa, Florida; Jacksonville, Florida; Brandon, Florida; Indianapolis, Indiana; Louisville, Kentucky; Brooklyn, New York; Rochester, New York; Columbus, Ohio; Dallas, Texas; Fort Worth, Texas; Plano, Texas; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Operation centers in Canada are located in Burlington, Ontario; and Toronto, Ontario.

Operations centers in the United Kingdom are located in Bournemouth, Edinburgh, Glasgow, London, Liverpool, and Swindon. The London location also serves as the European headquarters.

Additional offices and technology operations are located in Manila, Philippines; Cebu, Philippines; Mumbai, India; Bangalore, India; Hyderabad, India; New Delhi, India; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Sao Paulo, Brazil; Mexico City, Mexico, and Jerusalem, Israel.

In late 2017, JPMorgan Chase opened a new global operations center in Warsaw, Poland.[166]

Credit derivatives

The derivatives team at JPMorgan (including Blythe Masters) was a pioneer in the invention of credit derivatives such as the credit default swap. The first CDS was created to allow Exxon to borrow money from JPMorgan while JPMorgan transferred the risk to the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development. JPMorgan's team later created the 'BISTRO', a bundle of credit default swaps that was the progenitor of the Synthetic CDO.[167][168] As of 2013 JPMorgan had the largest credit default swap and credit derivatives portfolio by total notional amount of any US bank.[169][170]

Multibillion-dollar trading loss

In April 2012, hedge fund insiders became aware that the market in credit default swaps was possibly being affected by the activities of Bruno Iksil, a trader for JPMorgan Chase & Co., referred to as "the London whale" in reference to the huge positions he was taking. Heavy opposing bets to his positions are known to have been made by traders, including another branch of J.P. Morgan, who purchased the derivatives offered by J.P. Morgan in such high volume.[171][172] Early reports were denied and minimized by the firm in an attempt to minimize exposure.[173] Major losses, $2 billion, were reported by the firm in May 2012, in relation to these trades and updated to $4.4 billion on July 13, 2012.[174] The disclosure, which resulted in headlines in the media, did not disclose the exact nature of the trading involved, which remained in progress as of June 28, 2012, and continued to produce losses which could total as much as $9 billion under worst-case scenarios.[175][176] In the end, the trading produced actual losses of only $6 billion. The item traded, possibly related to CDX IG 9, an index based on the default risk of major U.S. corporations,[177][178] has been described as a "derivative of a derivative".[179][180] On the company's emergency conference call, JPMorgan Chase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon said the strategy was "flawed, complex, poorly reviewed, poorly executed, and poorly monitored".[181] The episode is being investigated by the Federal Reserve, the SEC, and the FBI.[182]

| Regulator | Nation | Fine |

|---|---|---|

| Office of the Comptroller of the Currency | US | $300m |

| Securities and Exchange Commission | $200m | |

| Federal Reserve | $200m | |

| Financial Conduct Authority | UK | £138m ($221m US) |

On September 18, 2013, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay a total of $920 million in fines and penalties to American and UK regulators for violations related to the trading loss and other incidents. The fine was part of a multiagency and multinational settlement with the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States and the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK. The company also admitted breaking American securities law.[184] The fines amounted to the third biggest banking fine levied by US regulators, and the second-largest by UK authorities.[183] As of September 19, 2013, two traders face criminal proceedings.[183] It is also the first time in several years that a major American financial institution has publicly admitted breaking the securities laws.[185]

A report by the SEC was critical of the level of oversight from senior management on traders, and the FCA said the incident demonstrated "flaws permeating all levels of the firm: from portfolio level right up to senior management."[183]

On the day of the fine, the BBC reported from the New York Stock Exchange that the fines "barely registered" with traders there, the news had been an expected development, and the company had prepared for the financial hit.[183]

Art collection

The collection was begun in 1959 by David Rockefeller,[186] and comprises over 30,000 objects, of which over 6,000 are photographic-based,[187] as of 2012 containing more than one hundred works by Middle Eastern and North African artists.[188] The One Chase Manhattan Plaza building was the original location at the start of collection by the Chase Manhattan Bank, the current collection containing both this and also those works that the First National Bank of Chicago had acquired prior to assimilation into the JPMorgan Chase organization.[189] L. K. Erf has been the director of acquisitions of works since 2004 for the bank,[190] whose art program staff is completed by an additional three full-time members and one registrar.[191] The advisory committee at the time of the Rockefeller initiation included A. H. Barr, and D. Miller, and also J. J. Sweeney, R. Hale, P. Rathbone and G. Bunshaft.[192]

Major sponsorships

- Chase Field (formerly Bank One Ballpark), Phoenix, Arizona – Arizona Diamondbacks, MLB

- Chase Center (San Francisco) – Golden State Warriors, NBA

- Major League Soccer

- Chase Auditorium (formerly Bank One Auditorium) inside of Chase Tower (Chicago) (formerly Bank One Tower)

- The JPMorgan Chase Corporate Challenge, owned and operated by JPMorgan Chase, is the largest corporate road racing series in the world with over 200,000 participants in 12 cities in six countries on five continents. It has been held annually since 1977 and the races range in size from 4,000 entrants to more than 60,000.

- JPMorgan Chase is the official sponsor of the US Open

- J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the Principal Sponsor of the English Premiership Rugby 7s Series

- Sponsor of the Jessamine Stakes, a two-year-old fillies horse race at Keeneland, Lexington, Kentucky since 2006.

The European Super League

On April 19, 2021, JP Morgan pledged $5 billion towards the European Super League.[193][194] a controversial breakaway group of football clubs seeking to create a monopolistic structure where the founding members would be guaranteed entry to the competition in perpetuity. While the absence of promotion and relegation is a common sports model in the US, this is an antithesis to the European competition-based pyramid model and has led to widespread condemnation from Football federations internationally as well as at government level.[195]

However, JPMorgan has been involved in European football for almost 20 years. In 2003, they advised the Glazer ownership of Manchester United. It also advised Rocco Commisso, the owner of Mediacom, to purchase ACF Fiorentina, and Dan Friedkin on his takeover of A.S. Roma. Moreover, It aided Inter Milan and A.S. Roma to sell bonds backed by future media revenue, and Spain's Real Madrid CF to raise funds to refurbish their Santiago Bernabeu Stadium.[196]

Leadership

Jamie Dimon is the chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase. The acquisition deal of Bank One in 2004, was designed in part to recruit Dimon to JPMorgan Chase. He became chief executive at the end of 2005.[197] Dimon has been recognized for his leadership during the 2008 financial crisis.[198] Under his leadership, JPMorgan Chase rescued two ailing banks during the crisis.[199] Although Dimon has publicly criticized the American government's strict immigration policies,[200] as of July 2018, his company has $1.6 million worth of stocks in Sterling Construction (the company contracted to build a massive wall on the U.S.-Mexico border).[201]

Board of directors

As of April 1, 2021:[202]

- Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase

- Linda Bammann, former JPMorgan and Bank One executive

- Steve Burke, chairman of NBCUniversal

- Todd Combs, CEO of GEICO

- James Crown, president of Henry Crown and Company

- Timothy Flynn, former chairman and CEO of KPMG

- Mellody Hobson, CEO of Ariel Investments

- Michael Neal, CEO of GE Capital

- Phebe Novakovic, chairwoman and CEO of General Dynamics

- Virginia Rometty, Executive Chairwoman of IBM, former chairwoman, President and CEO of IBM

Senior leadership

- Chairman: Jamie Dimon (since January 2007)[203]

- Chief Executive: Jamie Dimon (since January 2006)[203]

List of former chairmen

- William B. Harrison Jr. (2000–2006)[204]

List of former chief executives

- William B. Harrison Jr. (2000–2005)[204]

Notable former employees

Business

- Winthrop Aldrich – son of the late Senator Nelson Aldrich

- Andrew Crockett – former general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (1994–2003)

- Pierre Danon – chairman of Eircom

- Ina Drew – former CIO of JP Morgan Chase

- Dina Dublon – member of the board of directors of Microsoft, Accenture and PepsiCo and former Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of JPMorgan Chase

- Maria Elena Lagomasino – member of the board of directors of The Coca-Cola Company and former CEO of JPMorgan Private Bank

- Jacob A. Frenkel – Governor of the Bank of Israel

- Thomas W. Lamont – acting head of J.P. Morgan & Co. on Black Tuesday

- Charles Li – former CEO of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing

- Robert I. Lipp – former CEO of The Travelers Companies

- Marjorie Magner – chairman of Gannett Company[205]

- Henry S. Morgan – co-founder of Morgan Stanley, son of J. P. Morgan, Jr. and grandson of financier J. P. Morgan

- Lewis Reford – Canadian political candidate

- David Rockefeller – patriarch of the Rockefeller family

- Charlie Scharf – current CEO of Wells Fargo

- Harold Stanley – former JPMorgan partner, co-founder of Morgan Stanley

- Jes Staley – former CEO of Barclays

- Barry F. Sullivan – former CEO of First Chicago Bank and deputy mayor of New York City

- C. S. Venkatakrishnan – current CEO of Barclays

- Don M. Wilson III – former chief risk officer (CRO) of J. P. Morgan and current member of the board of directors at Bank of Montreal

- Ed Woodward – executive vice-chairman of Manchester United F.C.

Politics and public service

- Frederick Ma – Hong Kong Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (2007–08)

- Tony Blair – Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1997–2007)[206]

- William M. Daley – U.S. Secretary of Commerce (1997–2000), U.S. White House Chief of Staff (2011–2012)

- Michael Forsyth, Baron Forsyth of Drumlean – Secretary of State for Scotland (1995–97)

- Thomas S. Gates, Jr. – U.S. Secretary of Defense (1959–61)

- David Laws – UK Chief Secretary to the Treasury (May 2010) Minister of State for Schools

- Rick Lazio – member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1993–2001)

- Antony Leung – Financial Secretary of Hong Kong (2001–03)

- Dwight Morrow – U.S. Senator (1930–31)

- Margaret Ng – member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council

- Azita Raji – former United States ambassador to Sweden (2016–2017)

- George P. Shultz – U.S. Secretary of Labor (1969–70), U.S. Secretary of Treasury (1972–74), U.S. Secretary of State (1982–89)

- John J. McCloy – president of the World Bank, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank, chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations, a member of the Warren Commission, and a prominent United States adviser to all presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan

- Mahua Moitra – Former Vice President of JPMorgan Chase, Indian Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha

Awards

- Best Banking Performer, United States of America in 2016 by Global Brands Magazine Award.[209]

See also

- Credit default swap: History

- 2012 JPMorgan Chase trading loss

- Palladium Card

- Alayne Fleischmann

- Big Four banks

Index products

- JPMorgan EMBI

- JPMorgan GBI-EM Index

Further reading

- Horn, Martin (2022). J.P. Morgan & Co. and the Crisis of Capitalism: From the Wall Street Crash to World War II. Cambridge University Press.

References

- "J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. 2021 Form 10-K Annual Report". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- "JP Morgan Chase Annual Report 2021" (PDF). .jpmorganchase.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- "10-K". 10-K. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "1Q22 Earnings Supplement" (PDF). JPMorgan Chase. March 31, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- "Banks Ranked by Total Deposits". Usbanklocations.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- "History of Our Firm". JPMorganChase. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - de la Merced, Michael J. (June 16, 2008). "JPMorgan's Stately Old Logo Returns for Institutional Business". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- "History of Our Firm". JPMorgan Chase. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- "The History of J.P. Morgan Chase & Company" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- Schulz, Bill (July 29, 2016). "Hamilton, Burr and the Great Waterworks Ruse". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Hansell, Saul (August 29, 1995). "Banking's New Giant: The Deal; Chase and Chemical Agree to Merge in $10 Billion Deal Creating Largest U.s. Bank". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Hansell, Saul (September 3, 1996). "After Chemical Merger, Chase Promotes Itself as a Nimble Bank Giant". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Kahn, Joseph; McGeehan, Patrick (September 29, 1999). "Chase Agrees to Acquire Hambrecht & Quist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 11, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Journal, Michael R. SesitStaff Reporter of The Wall Street (April 12, 2000). "Chase to Acquire Robert Fleming In $7.73 Billion Stock-Cash Deal". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- Jimmy Lee's Global Chase Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, April 14, 1997

- Kingpin of the Big-Time Loan Archived September 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, August 11, 1995

- "JPMorgan Chase & Co. | American bank". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- McCreary, Matthew (August 14, 2018). "How Andrew Carnegie Went From $1.20 a Week to $309 Billion ... Then Gave It All Away". Entrepreneur. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Wile, Rob. "The True Story Of The Time JP Morgan Saved America From Default By Using An Obscure Coin Loophole". Business Insider. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Grant, Peter. "J.P. Morgan and the Panic of 1907: How one financier proved mightier than Wall Street". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "The Wall Street Bombing: Low-Tech Terrorism in Prohibition-Era New York". Slate. September 16, 2014. ISSN 1091-2339. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Wall Street bombing of 1920 | Facts, Theories, & Suspects". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy. Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 978-1-61016-308-8. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Steiner, Zara (2005). The lights that failed : European international history, 1919-1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-151881-2. OCLC 86068902. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- Journal, Michael Siconolfi and Anita RaghavanStaff Reporters of The Wall Street (February 6, 1997). "Securities Firms' Names Seem Anything but Firm". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "J.P. Morgan to buy Bank One for $58 billion - Jan. 15, 2004". money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Sorkin, Andrew Ross; Thomas, Landon Jr. (January 14, 2004). "J.P. Morgan Chase to Acquire Bank One in $58 Billion Deal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "JPMorgan Chase's Jamie Dimon Says He Has Curable Cancer". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Bank One | American company". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- "Coming up big: How Dimon turned JPMorgan Chase into a banking colossus". Crain's New York Business. May 20, 2019. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Hammer, Alexander R. (February 28, 1974). "First Banc Group Set to Acquire First National Bank of Toledo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Tracy, Justin Baer and Ryan (March 13, 2018). "Ten Years After the Bear Stearns Bailout, Nobody Thinks It Would Happen Again". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- CNBC.com (March 14, 2008). "Bear Stearns Gets Bailout From the Federal Reserve". www.cnbc.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Guerrera, Francesco (March 16, 2008). "Bear races to forge deal with JPMorgan". Financial Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- Quinn, James (March 19, 2008). "JPMorgan Chase bags bargain Bear Stearns". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- "JPMorgan Chase Completes Bear Stearns Acquisition (NYSE:JPM)". Investor.shareholder.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- Ellis, David. "JPMorgan buys WaMu" Archived November 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, CNNMoney, September 25, 2008.

- Hester, Elizabeth (September 26, 2008). "JPMorgan Raises $10 billion in Stock Sale After WaMu (Update3)". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- "WaMu Gives New CEO Mega Payout as Bank Fails". Fox News. September 26, 2008. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- "SEC Charges J.P. Morgan Chase In Connection With Enron's Accounting Fraud". Archived from the original on October 2, 2003.

- Johnson, Carrie (June 15, 2005). "Settlement In Enron Lawsuit For Chase". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "Wall Street firms to pay $1.4 billion in probe". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- Morgenson, Gretchen (March 17, 2005), "Bank to Pay $2 billion to Settle WorldCom Claims" Archived April 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times. Retrieved July 28, 2010

- Rovella, David E. & Baer, Justin (March 16, 2005), "JPMorgan to Pay $2 Bln to Settle WorldCom Fraud Suit" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved July 28, 2010

- "KCCLCC.net" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2009.

- Longstreth, Andrew; Stempel, Jonathan (July 24, 2012). "JPMorgan Chase settles with credit card customers for $100 million". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012.

- Braun, Martin Z. & Selway, William (November 4, 2009), "JPMorgan Ends SEC Alabama Swap Probe for $722 million" Archived January 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved July 28, 2010

- White, Anna (January 5, 2012). "PwC fined record £1.4m over JPMorgan audit". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- "UK fines JPMorgan record $49 mln, warns other banks" Archived September 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, FinanzNachrichten.de, Reuters, June 3, 2010

- "JPMorgan in record FSA fine for risking clients' money". BBC News. June 3, 2010. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- "No. 2 bank overcharged troops on mortgages" Archived September 23, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, NBC News, January 17, 2011

- Mui, Ylan Q. (April 23, 2011), "J.P. Morgan Chase to pay $27 million to settle lawsuit over military mortgages" Archived August 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, p. 9. Retrieved April 24, 2011

- "JPMorgan Chase Mortgage Chief Leaving After Military Scandal", Real Estate Journal Online. June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011 Archived June 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "JPMorgan dismisses mortgage head David Lowman", The Economic Times Delhi. Reuters. June 14, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011

- "JPMorgan Chase & Co" (Press release). Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- "Joint State-Federal Mortgage Servicing Settlement FAQ". Nationalmortgagesettlement.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- "Mortgage Plan Gives Billions to Homeowners, but With Exceptions". The New York Times. February 10, 2012. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- McLaughlin, David; Kopecki, Dawn (November 21, 2012). "JPMorgan Chase & Co". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on September 10, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "FERC, JPMorgan Unit Agree to $410 Million in Penalties, Disgorgement to Ratepayers". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. July 30, 2013. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Flitter, Emily (September 4, 2013). "Exclusive: JPMorgan subject of obstruction probe in energy case". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- "JPMorgan faces criminal and civil probes over mortgages". Reuters. August 7, 2013.

- JPMorgan agrees to $13 billion mortgage settlement Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. CNN. November 19, 2013.

- JPMorgan to pay $13 billion in deal with US Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. MSN Money. October 22, 2013.

- Merle, Renae. "JPMorgan Chase to pay $264 million in fines for bribing foreign officials by hiring their friends and family". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- "U.S. sues JPMorgan for alleged mortgage discrimination". Reuters. January 18, 2017. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- "U.S. accuses JPMorgan of mortgage discrimination in lawsuit". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- "SEC.gov | JPMorgan to Pay More Than $135 Million for Improper Handling of ADRs". www.sec.gov. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- "Madoff trustee suit against JPMorgan Chase" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Bob Van Voris. "JPMorgan Wins Dismissal of $19 Billion in Madoff Trustee Claims". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Stempel, Jonathan. "Madoff said JPMorgan executives knew of his fraud: lawsuit". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- "J P Morgan Chase pays $1.7 billion and settles Madoff related criminal case". Forbes. January 7, 2014. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- JPMorgan to pay $1.7bn to victims of the Madoff fraud Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine BBC January 7, 2014

- Text of deferred prosecution agreement in Madoff case Archived January 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Protess, Ben; Silver-Greenberg, Jessica. JPMorgan Faces Possible Penalty in Madoff Case Archived November 25, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, October 23, 2013.

- Chase to Acquire Collegiate Funding Services Archived December 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Business Wire, December 15, 2005

- "JPMorgan Chase completes acquisition of The Bank of New York's consumer, small-business and middle-market banking businesses". Investor.shareholder.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Vidal, John (March 26, 2008). "JPMorgan buys British carbon offset company". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "JPMorgan Buys Rest of Cazenove for 1 billion Pounds". Bloomberg. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010.

- Perez, Sarah (December 20, 2012). "Chase Acquires Local Offers Startup Bloomspot". Tech Crunch. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- Frojo, Renée (August 7, 2013). "Deals Site Bloomspot Bites The Dust". San Francisco Business Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- Son, Ryan Browne,Hugh (June 17, 2021). "JPMorgan is buying UK robo-advisor Nutmeg to boost overseas retail banking expansion". CNBC. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- "JPMorgan Chase buying spree set to be Jamie Dimon's biggest in years". Financial Times. July 6, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- Levitt, Hannah (March 15, 2022). "JPMorgan Agrees to Buy Share-Plan Software Company Global Shares". Bloomberg News.

- Goodbody, Will (August 11, 2022). "J.P. Morgan completes takeover of Cork's Global Shares". RTÉ.

- The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, company-published booklet, 2008, p. 19. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, company-published booklet, 2008, p. 6. Union National Bank and National Bank of Commerce in Houston were predecessor banks to TCB. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, company-published booklet, 2008, p. 3. New York Manufacturing Co. began in 1812 as a manufacturer of cotton processing equipment and switched to banking five years later. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, company-published booklet, 2008. Founder John Thompson named the bank in honor of his late friend, Salmon P. Chase. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- Other Successors to the break-up of The House of Morgan: Morgan Stanley and Morgan, Grenfell & Co.

- "The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking, company-published booklet, 2008, p. 5. Predecessor to J.P. Morgan & Co. was Drexel, Morgan & Co., est. 1871. Retrieved July 15, 2010. Other predecessors include Dabney, Morgan & Co. and J.S. Morgan & Co" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- The History of JPMorgan Chase & Co.: 200 Years of Leadership in Banking Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, company-published booklet, 2008, p. 3. The Marine Corp. merged in 1988 with BancOne. George Smith founded the Wisconsin Marine and Fire Insurance Co. in 1839, the predecessor company. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- On March 18, 2008, JPMorgan Chase announced the acquisition of Bear Stearns for $236 million, $2.00 per share. On March 24, 2008, a revised offer was announced at approximately $10 per share

- On September 25, 2008, JPMorgan Chase announced the acquisition of Washington Mutual for $1.8 billion.

- Delevingne, Lawrence (September 24, 2013). "Why Jamie Dimon and Bill Gates have teamed up". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- Chan, Cathy (October 2, 2014). "Hackers' Attack on JPMorgan Chase Affects Millions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- Goldstein, Matthew; Perlroth, Nicole; Sanger, David E. (October 3, 2014). "Hackers' Attack Cracked 10 Financial Firms in Major Assault". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- "JP Morgan sells commodity arm to Mercuria for $800 million" (Press release). Reuters. October 3, 2014. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- TimLoh, Tim Loh (March 7, 2016). "JPMorgan Won't Back New Coal Mines to Combat Climate Change". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "14 execs, JP Morgan Chase over tax fraud". AFP. December 3, 2016. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2017 – via Financial Express.

- "Ex-JPMorgan employee pleads guilty to $5 million fraud". Reuters. March 3, 2017. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- "Jamie Dimon just said the exec many saw as his successor is leaving JPMorgan". CNBC. June 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- "Nigeria sues JP Morgan for $875 million over Malabu oilfield deal Archived December 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. January 18, 2018.

- "JP Morgan says it knew ex-minister linked to firm in Nigeria oilfield deal Archived August 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". Reuters. April 6, 2018.

- "JP Morgan is rolling out the first US bank-backed cryptocurrency to transform payments business". CNBC. February 14, 2019. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "J.P. Morgan Chase Becomes First U.S. Bank With a Cryptocurrency". Fortune. February 14, 2019. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2019.