James Longstreet

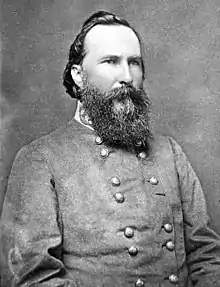

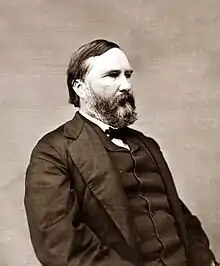

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821 – January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps commander for most of the battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia in the Eastern Theater, and briefly with Braxton Bragg in the Army of Tennessee in the Western Theater.

James Longstreet | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Minister to the Ottoman Empire | |

| In office December 14, 1880 – April 29, 1881 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Horace Maynard |

| Succeeded by | Lew Wallace |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 8, 1821 Edgefield District, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | January 2, 1904 (aged 82) Gainesville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Alta Vista Cemetery, Gainesville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Maria Louisa Garland

(m. 1848–1889)Helen Dortch (m. 1897) |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy Class of 1842 |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

After graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point, Longstreet served in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War. He was wounded in the thigh at the Battle of Chapultepec, and during recovery married his first wife, Louise Garland. Throughout the 1850s, he served on frontier duty in the American Southwest. In June 1861, Longstreet resigned his U.S. Army commission and joined the Confederate Army. He commanded Confederate troops during an early victory at Blackburn's Ford in July and played a minor role at the First Battle of Bull Run.

Longstreet made significant contributions to most major Confederate victories, primarily in the Eastern Theater as one of Robert E. Lee's chief subordinates in the Army of Northern Virginia. He performed poorly at Seven Pines by accidentally marching his men down the wrong road, causing them to arrive late, but played an important role in the Confederate success of the Seven Days Battles in the summer of 1862, where he helped supervise repeated attacks which drove the Union army away from the Confederate capital of Richmond. Longstreet led a devastating counterattack that routed the Union army at Second Bull Run in August. His men held their ground in defensive roles at Antietam and Fredericksburg. He did not participate in the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, as he and most of his soldiers had been detached on the comparatively minor Siege of Suffolk. Longstreet's most controversial service was at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, where he openly disagreed with General Lee on the tactics to be employed and reluctantly supervised several unsuccessful attacks on Union forces. Afterward, Longstreet was, at his own request, sent to the Western Theater to fight under Braxton Bragg, where his troops launched a ferocious assault on the Union lines at Chickamauga that carried the day. Afterward, his performance in semi-autonomous command during the Knoxville campaign resulted in a Confederate defeat. Longstreet's tenure in the Western Theater was marred by his central role in numerous conflicts amongst Confederate generals. Unhappy serving under Bragg, Longstreet and his men were sent back to Lee. He ably commanded troops during the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864, where he was seriously wounded by friendly fire. He later returned to the field, serving under Lee in the Siege of Petersburg and the Appomattox campaign.

Longstreet enjoyed a successful post-war career working for the U.S. government as a diplomat, civil servant, and administrator. His support for the Republican Party and his cooperation with his old friend, President Ulysses S. Grant, as well as critical comments he wrote about Lee's wartime performance, made him anathema to many of his former Confederate colleagues. His reputation in the South further suffered when he led African-American militia against the anti-Reconstruction White League at the Battle of Liberty Place in 1874. Authors of the Lost Cause movement focused on Longstreet's actions at Gettysburg as a principal reason for why the South lost the Civil War. As an elderly man, he married Helen Dortch Longstreet, a woman several decades younger than him, who after his death worked to restore her husband's image. Since the late 20th century, Longstreet's reputation has undergone a slow reassessment. Many Civil War historians now consider him among the war's most gifted tactical commanders.

Early life

Boyhood

James Longstreet was born on January 8, 1821, in Edgefield District, South Carolina,[1] an area that is now part of North Augusta, Edgefield County. He was the fifth child and third son of James Longstreet (1783–1833), of Dutch descent, and Mary Ann Dent (1793–1855) of English descent, originally from New Jersey and Maryland respectively, who owned a cotton plantation close to where the village of Gainesville would be founded in northeastern Georgia. James's ancestor Dirck Stoffels Langestraet immigrated to the Dutch colony of New Netherland in 1657, but the name became Anglicized over the generations.[2] James's father was impressed by his son's "rocklike" character on the rural plantation, giving him the nickname Peter, and he was known as Pete or Old Pete for the rest of his life.[3][4][5] Longstreet's father decided on a military career for his son but felt that the local education available to him would not be adequate preparation. At the age of nine, James was sent to live with his aunt Frances Eliza and uncle Augustus Baldwin Longstreet in Augusta, Georgia. James spent eight years on his uncle's plantation, Westover, just outside the city while he attended the Academy of Richmond County. His father died from a cholera epidemic while visiting Augusta in 1833. Although James's mother and the rest of the family moved to Somerville, Alabama, following his father's death, James remained with his uncle.[5][6]

As a boy, Longstreet enjoyed swimming, hunting, fishing, and riding horses. He became adept at shooting firearms. Northern Georgia was very rural frontier territory during Longstreet's boyhood, and Southern aristocratic traditions had not yet taken hold. As a result, Longstreet's manners were sometimes rather rough in spite of his plantation background. He dressed unceremoniously and at times used coarse language, although not in the presence of women. In his old age, Longstreet described his aunt and uncle as caring and loving.[7] He made no known political statements before the war and appears to have been largely uninterested in politics. But Augustus, as a lawyer, judge, newspaper editor, and Methodist minister, was a fierce states' rights partisan who supported South Carolina during the Nullification crisis (1828–1833), ideas to which Longstreet probably would have been exposed.[8][9] Augustus was also known for drinking whiskey and playing card games at a time when many Americans considered them immoral, habits he passed on to Longstreet.[8]

West Point and early military service

In 1837, Augustus attempted to obtain an appointment for his nephew to the United States Military Academy, but the vacancy for his congressional district had already been filled. Longstreet was instead appointed the following year by a relative Reuben Chapman, who represented the First District of Alabama, where Mary Longstreet lived. Longstreet was a poor student.[10] By his own admission in his memoirs, he "had more interest in the school of the soldier, horsemanship, exercise, and the outside game of foot-ball than in the academic courses".[11]

Longstreet ranked in the bottom third of every subject during his four years at the academy. In January of his third year, Longstreet initially failed his mechanics exam, but took a second test two days later and passed. Longstreet's engineering instructor in his fourth year was Dennis Hart Mahan, a man who stressed swift maneuvering, protection of interior lines, and positioning troops in strategic points rather than attempting to destroy the enemy's army outright. Although Longstreet earned modest grades in the course, he used similar tactics during the Civil War. Longstreet was also a disciplinary problem at West Point. He earned a large number of demerits, especially in his final two years. His offenses included visiting after taps, absence at roll call, an untidy room, long hair, causing a disturbance during study time, and disobeying orders. Biographer Jeffry D. Wert says, "Longstreet was neither a model student nor a gentleman."[12]

Longstreet was popular with his classmates, however, and befriended a number of men who would become prominent during the Civil War, including George Henry Thomas, William Rosecrans (his West Point roommate), John Pope, Daniel Harvey Hill, Lafayette McLaws, George Pickett, and Ulysses S. Grant. Longstreet ranked 54th out of 56 cadets when he graduated in 1842. He was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the United States Army.[13][14][15]

After a brief furlough, Longstreet was stationed for two years at the 4th U.S. Infantry at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, under the command of Lieutenant colonel John Garland.[16] In 1843, he was joined by his friend, Lieutenant Ulysses Grant.[17] In 1844, Longstreet met Garland's daughter and his future first wife Maria Louisa Garland, called Louise by her family.[17] At about the same time as Longstreet began courting Louise, Grant courted Longstreet's fourth cousin, Julia Dent, and that couple eventually married. Longstreet attended the Grant wedding on August 22, 1848, in St. Louis, but his role at the ceremony remains unclear. Grant biographers Jean Edward Smith and Ron Chernow state that Longstreet served as Grant's best man at the wedding.[18][19] John Y. Simon, editor of Julia Grant's memoirs, concluded that Longstreet "may have been a groomsman", and Longstreet biographer Donald Brigman Sanger called the role of best man "uncertain" while noting that neither Grant nor Longstreet mentioned such a role in either of their memoirs.[20]

Later in 1844, the regiment, along with the Third Infantry, was transferred to Camp Salubrity near Natchitoches, Louisiana, as part of the Army of Observation under Major General Zachary Taylor. On March 8, 1845, Longstreet received a promotion to second lieutenant, and was transferred to the Eighth Infantry, stationed at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. He served for the month of August on court-martial duty in Pensacola. The regiment was then transferred to Corpus Christi, Texas, where he was reunited with the officers of the Third and Fourth Regiments, including Grant. The men passed the winter by staging plays.[21]

Mexican–American War

Longstreet served with distinction in the Mexican–American War with the 8th U.S. Infantry. He fought under Zachary Taylor as a lieutenant in May 1846 in the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma.[22] He recounted both of these battles in his memoirs but wrote nothing about his personal role in them.[23] On June 10, Longstreet was given command of Company A of the Eighth Infantry of William J. Worth's Second Division. He fought again with Taylor's army at the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846. During the battle, about 200 Mexican lancers drove back a group of American troops. Longstreet, commanding companies A and B, led a counterattack, killing or wounding almost half of the lancers.[24]

On February 23, 1847, he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant. General-in-Chief Winfield Scott ordered Worth's division out of Taylor's army and under his direct command in order to participate in an assault on the Mexican capital of Mexico City. Worth's division was sent first to Lobos Island. From there it sailed 180 miles (289.7 km) south to the city of Veracruz. Worth led Scott's army in its amphibious approach on the city, arriving there on March 9. Scott besieged the city and subjected it to regular bombardments. It surrendered on March 29. The American army then marched north towards the capital.[25] In August, Longstreet served in the Battle of Churubusco, a pivotal battle as the U.S. Army moved closer to capturing Mexico City. The Eighth Infantry was the only force in Worth's division to reach the Mexican earthworks. Longstreet carried the regimental banner under heavy Mexican fire. The troops found themselves stuck in a ditch and could only scale the Mexican defenses by standing on each other. In the fierce hand-to-hand combat that ensued, the Americans prevailed. Longstreet received a brevet promotion to captain for his actions at Churubusco.[26]

He received a brevet promotion to major for Molino del Rey. In the Battle of Chapultepec on September 12, he was wounded in the thigh while charging up the hill with his regimental colors; falling, he handed the flag to his friend, Lt. Pickett, who was able to reach the summit. The capture of the Chapultepec fortress led to the fall of Mexico City.[15][27] Longstreet recovered in the home of the Escandón family, which treated wounded American soldiers. His wound was slow to heal and he did not leave the home until December. After a brief visit with his family, Longstreet went to Missouri to see Louise.[28]

Subsequent activities

After the war and his recovery from the Chapultepec wound, Longstreet and Louise Garland were officially married on March 8, 1848,[29] and the marriage produced 10 children.[30] Little is known of their courtship or marriage. Longstreet rarely mentions her in his memoirs, and never reveals any personal details. There are no surviving letters between the two. Most anecdotes about their relationship come through the writings of Longstreet's second wife, Helen Dortch Longstreet.[17] Novelist Ben Ames Williams, a descendant of Longstreet, included Longstreet as a minor character in two of his novels. Williams questioned Longstreet's surviving children and grandchildren, and in the novels depicted him as a very devoted family man with an exceptionally happy marriage.[31]

Longstreet's next assignment placed him on recruiting duty in Poughkeepsie, New York, where he served for several months. After travelling to St. Louis for the Grant wedding, Longstreet and his wife moved to Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania.[29] On January 1, 1850, he was appointed Chief Commissary for the Department of Texas, responsible for the acquisition and distribution of food to the soldiers and animals of the department. The job was complex and consisted mainly of paperwork, although it provided experience in administrative military work. In June, Longstreet, hoping to find promotion and an income above his $40-per month salary to support his growing family, requested a transfer to the cavalry. His request was rejected. He resigned as commissary in March 1851 and returned to the Eighth Infantry. [32] Longstreet served on frontier duty in Texas at Fort Martin Scott near Fredericksburg. The primary purpose of the military in Texas was to protect frontier communities against Indians, and Longstreet frequently participated in scouting missions against the Comanche. His family remained in San Antonio, and he saw them regularly.[32] In 1854, he was transferred to Fort Bliss in El Paso, and Louise and the children moved in with him. In 1855, Longstreet was involved in fighting against the Mescalero. He assumed command of the garrison at Fort Bliss on two occasions between the spring of 1856 and the spring of 1858. The small size of the garrison allowed for easy socialization with the local people, and the fort's location allowed for visits with Louise's parents in Santa Fe.[33] Longstreet performed scouting missions.[15][34]

On March 29, 1858, Longstreet wrote to the adjutant general's office in Washington, D.C. requesting that he be assigned to recruiting duty in the East, which would allow him to better educate his children. He was granted a six-month leave, but the request for assignment in the East was denied, and he was instead directed to serve as major and paymaster for the 8th Infantry in Leavenworth, Kansas. He left his son Garland in a school at Yonkers, New York, before journeying to Kansas. On the way, Longstreet came across his old friend Grant in St. Louis, Missouri. Longstreet's time in Leavenworth lasted about a year until he was transferred to Colonel Garland's department in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to serve as paymaster, where he was joined by Louise and their children.[35][36]

Knowledge of Longstreet's prewar life is extremely limited. His experience resembles that of many Civil War generals insofar as he went to West Point, served with distinction in the War with Mexico, and continued his career in the peacetime army of the 1850s. But beyond that, there are few details. He left no diary, and his lengthy memoirs focus almost entirely on recounting and defending his Civil War military record. They reveal little of his personal side while providing only a very cursory view of his pre-war activities. Not only that, but an 1889 fire destroyed his personal papers, making it so that the number of "[e]xisting antebellum private letters written by Longstreet [could] be counted on one hand".[37]

American Civil War

Joining the Confederacy and initial hostilities

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Longstreet was paymaster for the United States Army and stationed in Albuquerque, having not yet resigned his commission. After news of the Battle of Fort Sumter, he joined his fellow Southerners in leaving the post. In his memoirs, Longstreet calls it a "sad day", and records that a number of Northern officers attempted to persuade him not to go. He writes that he asked one of them "what course he would pursue if his State should pass ordinances of secession and call him to its defence. He confessed that he would obey the call."[38]

Longstreet was not enthusiastic about secession from the Union, but he had long been infused with the concept of states' rights and felt he could not go against his homeland.[39] Although he was born in South Carolina and brought up in Georgia, he offered his services to the state of Alabama, which had appointed him to West Point and where his mother still lived. He was the senior West Point graduate from that state, which meant that he could potentially be placed in command of that state's soldiers.[40] After settling his accounts, he submitted his resignation letter from the United States Army on May 9, 1861, intending to join the Confederacy. He had already accepted a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate States Army on May 1, before submitting his resignation from the United States Army. His resignation from the United States Army was accepted on June 1.[41]

Longstreet arrived in Richmond, Virginia, with his new commission. He met with Confederate President Jefferson Davis at the executive mansion on June 22, 1861, where he was informed that he had been appointed a brigadier general with the date of rank on June 17, a commission he accepted on June 25. He was ordered to report to Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard at Manassas, where he was given command of a brigade of three Virginia regiments—the 1st, 11th, and 17th Virginia Infantry regiments in the Confederate Army of the Potomac.[42][43]

Longstreet assembled his staff and trained his brigade incessantly. On July 16, Union Brigadier General Irvin McDowell began marching his army toward Manassas Junction. Longstreet's brigade first saw action at Blackburn's Ford on July 18, when it collided with McDowell's advance division under Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, clashing heavily with the brigade of Israel B. Richardson.[44][45] An infantry charge pushed Longstreet's men back, and in his own words Longstreet "rode with sabre in hand for the leading files, determined to give them all that was in the sword and my horse's heels, or stop the break".[46] Colonel Jubal Early's brigade arrived to reinforce Longstreet. One of Early's regiments, the 7th Virginia, fired a volley while Longstreet was still in front of its position, forcing him to dive off of his horse and onto the ground. Under the renewed Confederate strength, the Union left wavered. Tyler withdrew, as he had orders not to bring on a general engagement.[47][48]

The battle preceded the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas). When the main attack came at the opposite end of the line on July 21, Longstreet's brigade endured artillery fire for nine hours but played a minor role in the fighting.[49][50] Between 5 and 6 in the evening, Longstreet received an order from Brigadier General Joseph E. Johnston instructing him to take part in the pursuit of the Federal troops, who had been defeated and were fleeing the battlefield. He obeyed, but when he met Brigadier General Milledge Bonham's brigade, Bonham, who outranked Longstreet, ordered him to retreat. An order soon arrived from Johnston ordering the same. Longstreet was infuriated that his commanders would not allow a vigorous pursuit of the defeated Union Army.[51] His Chief of Staff, Moxley Sorrel, recorded that he was "in a fine rage. He dashed his hat furiously to the ground, stamped, and bitter words escaped him."[52] He quoted Longstreet as saying afterward, "Retreat! Hell, the Federal army has broken to pieces."[52]

On October 7, Longstreet was promoted to major general and assumed command of a division in the newly reorganized and renamed Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under Johnston (formed from the previous Army of the Potomac and the Army of the Shenandoah) – with four infantry brigades commanded by Generals D.H. Hill, David R. Jones, Bonham, and Louis Wigfall, as well as Hampton's Legion commanded by Wade Hampton III.[53]

Family tragedy

On January 10, 1862, Longstreet traveled under orders from Johnston to Richmond, where he discussed with Davis the creation of a draft or conscription program. He spent much of the intervening time with Louise and their children, and was back at army headquarters in Centreville by January 20. After only a day or two, he received a telegram informing him that all four of his children were extremely sick in an outbreak of scarlet fever. Longstreet immediately returned to the city.[54]

Longstreet arrived in Richmond before the death of his one-year-old daughter Mary Anne on January 25. Four-year-old James died the following day. Eleven-year-old Augustus Baldwin ("Gus") died on February 1. His 13-year-old son Garland remained ill but appeared to be out of mortal danger. George Pickett and his future wife LaSalle Corbell were in the Longstreets' company throughout the affair. They arranged the funeral and burials, which for unknown reasons neither Longstreet nor his wife attended. Longstreet waited a very short time to return to the army, doing so on February 5. He rushed back to Richmond later in the month when Garland took a turn for the worse, but came back after he recovered. The losses were devastating for Longstreet and he became withdrawn, both personally and socially. In 1861, his headquarters were noted for parties, drinking, and poker games. After he returned, the headquarters social life became for a time more somber. He rarely drank, and his religious devotion increased.[55][56]

Peninsula

That spring, Union Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, launched the Peninsula campaign intending to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond.[57] In his memoirs, Longstreet would write that while in temporary command of the Confederate army, he wrote to Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson proposing that he march to Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley and combine forces. No evidence has emerged for this claim.[58][59]

Following the delay of the Union offensive against Richmond at the Siege of Yorktown, Johnston oversaw a tactical withdrawal to the outskirts of Richmond, where defenses had already been prepared. Longstreet's division formed the rearguard, which was heavily engaged at the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5. There, Union troops beginning with Joseph Hooker's division of the Union III Corps, which was commanded by Samuel P. Heintzelman, came out of a forest into open ground to attack Longstreet's men.[60] To protect the army's supply wagons, Longstreet launched a counterattack with the brigades of Cadmus M. Wilcox, A. P. Hill, Pickett, Raleigh E. Colston, and two other regiments. The assault drove the Union soldiers back. Finding the ground he occupied untenable, Longstreet requested reinforcements from D.H. Hill's division a little further up the road and received Early's brigade, to which was later added the entire division.[61][62] Early then launched a fruitless and bloody attack well after the wagons had already been safely evacuated. Overall, the battle was a success, protecting the passage of Confederate supply wagons and delaying the advance of McClellan's army toward Richmond.[63] The affair gave the Confederates possession of four cannon.[64] McClellan inaccurately characterized the battle as a Union victory in a dispatch to Washington.[60][65]

On May 31, during the Battle of Seven Pines, Longstreet received his orders verbally from Johnston but apparently misremembered them. He marched his men in the wrong direction down the wrong road, causing congestion and confusion with other Confederate units, diluting the effect of the Confederate counterattack against McClellan. He then got into an argument with Major General Benjamin Huger over who had seniority, causing a significant delay.[66] When D.H. Hill subsequently asked Longstreet for reinforcements, he complied, but failed to properly coordinate his brigades.[67] Only one of Longstreet's brigades and none of Huger's reached the field.[68] Late in the day, Major General Edwin Vose Sumner crossed the rain-swollen Chickahominy River with two divisions.[69] General Johnston was wounded during the battle. Although Johnston preferred Longstreet as his replacement, command of the Army of Northern Virginia shifted to G. W. Smith, the senior major general, for a single day.[70] On June 1, Richardson's division of Sumner's corps engaged Longstreet's men, routing Lewis Armistead's brigade, but the brigades of Pickett, William Mahone, and Roger Atkinson Pryor positioned in the woods managed to hold it back. After six hours of fighting, the battle ended in a draw.[71] Johnston praised Longstreet's performance in the battle. Biographer William Garrett Piston marks it as "the lowest point in Longstreet's military career".[66] Longstreet's report unfairly blamed Huger for the mishaps.[72] On June 1, the President's military advisor Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia. In his memoirs, Longstreet suggested that he initially doubted Lee's capacity for command. He wrote that his arrival "was far from reconciling the troops to the loss of our beloved chief, Joseph E. Johnston".[73] He wrote that Lee did not have much of a reputation at the time that he took command and that there were, therefore "misgivings" about Lee's "power and skill for field service".[73]

In late June, Lee organized a plan to drive McClellan's army away from the capital, which culminated in what became known as the Seven Days Battles. At daybreak on June 27 at Gaines's Mill, the Confederate Army attacked the V Corps of the Union Army under Brigadier General Fitz John Porter, which was positioned north of the Chickahominy River on McClellan's right flank. Federal troops held their lines for most of the day against attacks from the divisions of A.P. Hill and D.H. Hill, and Jackson did not arrive until the afternoon. At about 5 P.M., Longstreet received orders from Lee to join the battle. Longstreet's fresh brigades under Pickett and Richard H. Anderson, accompanied by the brigades of Brigadier General John Bell Hood and Colonel Evander M. Law from William H.C. Whiting's division, charged the Union lines, forcing them to retreat across the Chickahominy.[74][75][76] Longstreet was engaged again on June 30 with about 20,000 men at Glendale.[77] He departed from his usual strategy of placing troops several lines deep and instead spread them out, which in the opinion of some military historians cost him the battle. His efforts were further damaged by the slowness of other Confederate commanders, and McClellan was able to withdraw his army to the high plateau of Malvern Hill.[78] Jackson, engaged at White Oak Swamp, ignored reports of ways in which to cross the swamp, and refused to answer an inquiry from Longstreet's staff officer John Fairfax. Huger's advance was slow enough to allow Federal troops to be transported away from guarding him and towards Longstreet, and Theophilus Holmes also performed poorly. Nearly 50,000 Confederate troops stood within a few miles of the field at Glendale and rendered little to no assistance.[79] In a reconnaissance on the evening of June 30, Longstreet reported to Lee that conditions were favorable enough to justify assault. At the Battle of Malvern Hill the next day, Longstreet surrendered A.P. Hill's entire division to Magruder, and marched his remaining troops toward the Union positions on the Confederate extreme right. His men were exposed to fire on their flanks from McClellan's troops and were forced to withdraw without success.[80]

Throughout the Seven Days Battles, Longstreet had operational command of nearly half of Lee's army—15 brigades—as it drove McClellan back down the Peninsula. Longstreet performed aggressively and quite well in his new, larger command, particularly at Gaines's Mill and Glendale. Lee's army suffered from poor maps, organizational flaws, and weak performances by Longstreet's peers, including, uncharacteristically, Stonewall Jackson, and was unable to destroy the Union army.[50][72][81] Moxley Sorrel wrote of Longstreet's confidence and calmness in battle: "He was like a rock in steadiness when sometimes in battle the world seemed flying to pieces." General Lee said shortly after Seven Days, "Longstreet was the staff in my right hand."[82] He had been established as Lee's principal lieutenant.[83] Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia after Seven Days, increasing Longstreet's command from six brigades to 28.[84] Longstreet took command of the Right Wing (later to become known as the First Corps) and Jackson was given command of the Left Wing.[85] Over time, Lee and Longstreet became good friends and set up headquarters very near each other. Despite sharing with Jackson a belief in temperance as well as a deep religious conviction, Lee never developed as strong a friendship with him. Piston speculates that the more relaxed atmosphere of Longstreet's headquarters, which included gambling and drinking, allowed Lee to relax and take his mind off the war, and reminded him of his happier younger days.[86]

After the campaign, an editorial appeared in the Richmond Examiner inaccurately claiming that the Battle of Glendale "was fought exclusively by General A.P. Hill and the forces under his command". Longstreet then drafted a letter refuting the article, which was published in the Richmond Whig. Hill took offense and requested that his division be transferred out of Longstreet's command. Longstreet agreed, but Lee took no action. Then, Hill refused to accede to Longstreet's repeated requests for information and was eventually arrested on Longstreet's orders. He challenged Longstreet to a duel. Longstreet accepted, but Lee intervened and transferred Hill's division out of Longstreet's command and into Jackson's.[87]

Second Bull Run

The military reputations of Lee's corps commanders are often characterized as Stonewall Jackson representing the audacious, offensive component of Lee's army, with Longstreet more typically advocating and executing strong defensive strategies and tactics. Wert describes Jackson as the hammer and Longstreet as the anvil of the army.[88] In the first part of the Northern Virginia campaign of August 1862, this stereotype held true, but in the climactic battle, it did not. In June, the Federal Government created the 50,000-strong Army of Virginia, and put Major General John Pope in command.[89] Pope moved south in an attempt to attack Lee and threaten Richmond through an overland march. Lee left Longstreet near Richmond to guard the city and dispatched Jackson to hinder Pope's advance. Jackson won a major victory at the Battle of Cedar Mountain.[90] After learning that McClellan, as ordered, had dispatched troops north to assist Pope, Lee ordered Longstreet north as well, leaving only three divisions under G.W. Smith to protect Richmond against McClellan's reduced force. Longstreet's men began their march on August 17, aided by Stuart's cavalry.[91] On August 23, Longstreet engaged Pope's position in a minor artillery duel at the First Battle of Rappahannock Station. The Confederate Washington Artillery was heavily damaged and a Union shell landed feet away from Longstreet and Wilcox but failed to explode. Meanwhile, Stuart's cavalry rode around the Army of Virginia and captured hundreds of soldiers and horses as well as some of Pope's personal belongings.[92]

Jackson executed a sweeping flanking maneuver that captured Pope's main supply depot. He placed his corps in the rear of Pope's army, but he then took up a defensive position and effectively invited Pope to assault him. On August 28 and 29, the start of the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas), Pope pounded Jackson as Longstreet and the remainder of the army marched from the west, through Thoroughfare Gap, to reach the battlefield. On the afternoon of the 28th, Longstreet engaged a 5,000-man federal division under James B. Ricketts at the Battle of Thoroughfare Gap. Ricketts had been ordered to delay Longstreet's march towards the main Confederate army, but he took up his position too late, allowing George T. Anderson's brigade to occupy the high ground. Lee and Longstreet watched the battle together and decided to flank the Union position. Hood's division and a brigade under Henry L. Benning advanced towards the gap from the north and the south, respectively, while Wilcox's division followed in a six-mile march northward. Ricketts realized his position was untenable and withdrew that evening, allowing Longstreet to join up with the rest of Lee's army. Postwar criticism of Longstreet claimed that he marched his men too slowly, leaving Jackson to bear the brunt of the fighting for two days, but they covered roughly 30 miles (50 km) in a little over 24 hours and Lee did not attempt to get his army concentrated any faster.[93]

When Longstreet's men arrived on the field at around midday on August 29, Lee planned a flanking attack on the Union Army, which was concentrating its attention on Jackson. Longstreet demurred to three suggestions from Lee urging him to attack, recommending instead that a reconnaissance in force be conducted to survey the ground in front of him. This was done and confirmed the presence of Porter's V Corps in front of his lines. By 6:30 P.M., Hood's division moved forward against Porter and drove back the soldiers it encountered, but had to be withdrawn at night when it advanced too far ahead of the main lines. Despite the smashing victory that followed, Longstreet was eventually criticized for allegedly being slow, reluctant to attack, and disobedient to General Lee.[55][94][95] Lee's biographer, Douglas Southall Freeman, wrote: "The seeds of much of the disaster at Gettysburg were sown in that instant—when Lee yielded to Longstreet and Longstreet discovered that he would."[96] Wert disputes this conclusion, pointing out that in a post-war letter to Longstreet, Porter told him that had he attacked him that day, Longstreet's "loss would have been enormous".[97]

Despite this criticism, the following day, August 30, was, according to Wert, one of Longstreet's finest performances of the war. After his attacks on the 29th, Pope came to believe with little evidence that Jackson was in retreat.[98] He ordered a reluctant Porter to move his corps forward in pursuit, and they collided with Jackson's men and suffered heavy casualties. The attack exposed the Union left flank, and Longstreet took advantage of this by launching a massive assault on the Union flank with over 25,000 men. For over four hours they "pounded like a giant hammer"[99] with Longstreet actively directing artillery fire and sending brigades into the fray. Longstreet and Lee were together during the assault and both of them came under Union artillery fire. Although the Union troops put up a furious defense, Pope's army was forced to retreat in a manner similar to the embarrassing Union defeat at First Bull Run, fought on roughly the same battleground.[72][100] Longstreet gave all of the credit for the victory to Lee, describing the campaign as "clever and brilliant". It established a strategic model he believed to be ideal—the use of defensive tactics within a strategic offensive.[101] On September 1, Jackson's corps moved to cut off the Union retreat at the Battle of Chantilly. Longstreet's men remained on the field in order to fool Pope into thinking that Lee's entire army was still on his front.[102]

Antietam

After the Confederate success at Second Manassas, Lee, holding the strategic initiative, decided to take the war to Maryland to relieve Virginia and hopefully induce foreign nations to come to the Confederates' aid. Longstreet supported the plan. "The situation called for action", he later said, "and there was but one opening – across the Potomac."[103][104] His men crossed into Maryland on September 6 and arrived in Frederick the following day, beginning the Maryland campaign.[103] At the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) on September 17, rather than commit his forces all at once, McClellan instead made a series of partial attacks on Confederate troops at different times and places throughout the day while holding many of his troops, including the entire V Corps, in reserve. At dawn, Hood's division on the Confederate left was driven back by an assault from Hooker's and Joseph K. Mansfield's corps until reinforced by men from Jackson's command. More troops from both sides soon poured into the fighting, which raged for three hours.[105][106] At the center of the field, D.H. Hill's division defended a 600-yard (548.6 meters) position dominated by a sunken road created by years of farmers' wagons being wheeled over a path. The position was naturally strong, made more so by the piling of planks from a wooden fence at the top of the ditch, and Hill's men firmly repulsed two successive charges from the Union divisions of William H. French and Richardson. Hill suffered significant casualties, and Longstreet sent R.H. Anderson's division, which consisted of 3,500 men, to reinforce him. Anderson was wounded and replaced by Pryor. At Pryor's request, Longstreet sent artillery support in response to Union cannon being fired at Confederates in the road from across Antietam Creek. He also ordered a flanking movement by about 900 soldiers in several regiments led by Colonel John Rogers Cooke. Union troops arrested Cooke's advance. An intense fight followed, and Cooke withdrew after his ammunition was expended. A mistaken order allowed Union troops to breach the Confederate position at the sunken road, but Confederate lines were stabilized.[107]

At this point in the afternoon, fighting largely ceased except for on the Confederate right. The Union left-wing under Major General Ambrose Burnside attempted to cross the Antietam Creek at what would become known as Burnside's Bridge, while Jones' division led by Brigadier General Robert Toombs's brigade defended the heights on the western side of the creek. For hours, the Union troops tried to cross the river and failed five times.[108][109][110] Finally at 4 P.M., a flanking maneuver forced Toombs to withdraw. After the further engagement, the remainder of Jones' division was forced to give way, and Burnside's men occupied the crest overlooking the river before pressing their advantage. Their progress was arrested by the arrival of A.P. Hill's division under Jackson from Harpers Ferry. Fighting ensued in the town of Sharpsburg until Burnside withdrew his men at dusk. The Confederates pursued their enemy but stopped once the retreating troops came under the protection of a battery on the opposite side of the river, ending the Battle of Antietam after 18 hours of fighting.[111][112][113] At the end of that bloodiest day of the Civil War, Lee greeted his subordinate by saying, "Ah! Here is Longstreet; here's my old war-horse!"[114] Lee held his ground at Antietam until the evening of September 18, when he withdrew his army from the battlefield and took it back across the Potomac and into Virginia.[115][116] On October 9, a few weeks after Antietam, Longstreet was promoted to lieutenant general. Lee arranged for Longstreet's promotion to be dated one day earlier than Jackson's, making the Old War-Horse the senior lieutenant general in the Army of Northern Virginia. In an army reorganization in November, Longstreet's command was designed the First Corps, and Jackson's the Second Corps. The First Corps consisted of five divisions, approximately 41,000 men. The divisions were commanded by Lafayette McLaws, R.H. Anderson, Hood, Pickett, and Robert Ransom Jr.[117][118]

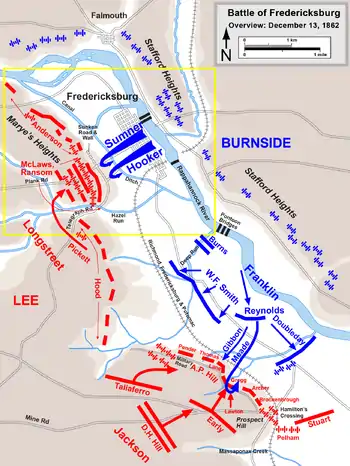

Fredericksburg

After a lengthy interlude with little military activity, beginning on October 26, McClellan marched his army across the Potomac River. On November 7, Lincoln replaced McClellan with Burnside. On November 15, Burnside began moving his army south towards Fredericksburg, Virginia, midway between the opposing capitals.[119] On November 18, Longstreet began marching his men out of army headquarters in Culpeper towards Fredericksburg, where the Confederate army would make its stand against Burnside. Since Lee moved Longstreet to Fredericksburg early, it allowed Longstreet to build strong defenses. Longstreet ordered trenches, abatis, and fieldworks to be constructed south of the town along a stone wall at the foot of Marye's Heights. After a lengthy delay, caused by waiting for the arrival of supplies to build pontoon bridges, Burnside attempted to cross the Rappahannock on December 11. Soldiers attempting to lay pontoon bridges encountered fierce resistance from Confederate troops inside of Fredericksburg, led by William Barksdale's brigade of McLaws' division. Burnside subsequently ordered an artillery bombardment of the town, and by the following day had moved his army across and occupied Fredericksburg.[120][121] December 12 saw only a small amount of desultory fighting.[122]

Longstreet had his men firmly entrenched along Marye's Heights. On December 13, under Burnside's orders, troops from the Union Right Grand Division under Sumner and the Center Grand Division under Hooker undertook to carry the position held by Longstreet's troops, who, contrary to some of their expectations, found themselves at the center of the battle. The first Union assault on Longstreet's men at Marye's Heights was a disastrous failure, causing approximately 1,000 casualties within 30 minutes.[123][124] When Lee expressed apprehension that the Federal troops might overrun Longstreet's men, Longstreet replied that as long as he had sufficient ammunition he would "kill them all" before any of them reached his line.[125] He advised him to look towards Jackson's more tenuous position to the right. Longstreet was proven correct, as from their strong position his troops easily repulsed several more assaults. In some places behind the stone wall, Confederate ranks were four to five troops deep. Soldiers in the rear loaded rifles and passed them up to the front, making it so that the fire coming from behind the wall was virtually continuous. Confederate troops were well protected, although they did suffer one notable casualty when Brigadier General Thomas Reade Rootes Cobb, who commanded a brigade in McLaws' division that was positioned at the front of the stone wall, was killed.[126][127][128] One Union general compared the scene before Marye's Heights to "a great slaughter pen" and said that his men "might as well have tried to take Hell".[125] McLaws estimated that only one Union soldier lay dead within 30 yards of the wall, the rest having fallen much farther back. Jackson, meanwhile, managed with much greater difficulty to repel a strong Union assault spearheaded by the division of George Meade. Sensing that the rest of his troops would be adequate to defend his position on the Confederate left on the heights, Longstreet had ordered Hood to reinforce Jackson, and Pickett to cooperate with him, but Hood hesitated in sending his division forward, and by the time he finally did, the fighting on Jackson's front had mostly ended.[126][129][130] Speaking about Hood, Longstreet expressed regret after the war for "not bringing the delinquent to trial".[131]

Burnside intended to attack again the next day, but several of his officers, particularly Sumner, advised him against it. He entrenched his men instead and withdrew on December 15. In Longstreet's report, he praised his men and officers while asking them to contribute money for the residents of Fredericksburg. Lee's report strongly commended Jackson and Longstreet.[132] Burnside's army had suffered 12,653 casualties at Fredericksburg. About 70% of them were in front of Marye's Heights.[133] Lee suffered only about 5,300 losses, about 1,900 of which came from Longstreet.[134] Lt. Col. Edward Porter Alexander of the artillery described Fredericksburg as "the easiest battle we ever fought."[135]

Suffolk

In October 1862, Longstreet had suggested to Joe Johnston that he be sent to fight in the war's Western Theater.[88] Shortly after Fredericksburg, Longstreet vaguely suggested to Lee that "one corps could hold the line of the Rappahannock while the other was operating elsewhere".[136] In February 1863, he made a more specific request, suggesting to Wigfall that his corps be detached from the Army of Northern Virginia and sent to reinforce the Army of Tennessee, where General Braxton Bragg was being challenged in Middle Tennessee by the Army of the Cumberland under Union Major General William S. Rosecrans, Longstreet's roommate at West Point.[137] By this time, Longstreet could be identified as part of a "western concentration bloc" which believed that reinforcing Confederate armies operating in the Western Theater to protect the states in that part of the Confederacy from invasion was more important than offensive campaigns in the Eastern Theater. This group also included Johnston and Louis Wigfall, now a Confederate senator, both of whom Longstreet was very close with. These people were generally cautious and believed that the Confederacy, with its limited resources, should engage in a defensive rather than an offensive war.[138] Lee did detach two divisions from the First Corps but ordered them to Richmond, not Tennessee.[15][139] The Confederate Army was suffering from an acute food shortage. Southern Virginia was said to have large quantities of cattle and substantial stores of bacon and corn.[140] Meanwhile, seaborne movements of the Union IX Corps were thought to be aimed at launching an invasion of the Confederate coast anywhere from South Carolina to Southern Virginia. In response, Lee ordered Pickett's division to the capital in mid-February. Hood's division followed, and then Longstreet himself was told to take command of the detached divisions and the Departments of North Carolina and Southern Virginia.[15][139] The divisions of McLaws and Anderson remained with Lee.[141]

In March, Longstreet's men primarily conducted foraging expeditions in Virginia and North Carolina. Longstreet sent Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett's brigade to D.H. Hill to participate in Hill's attempt to capture New Bern, a town on the North Carolina coast which had fallen to the Union in March 1862. The campaign was unsuccessful but netted a considerable amount of supplies.[142] In April, Longstreet besieged Union forces in the city of Suffolk, Virginia. Fighting was light and nothing came of the siege. At the end of April, Longstreet was ordered by Secretary of War James Seddon to join Lee's army as it faced attack from the Army of the Potomac, now commanded by Hooker, at the Battle of Chancellorsville. He moved his divisions north but could not reach the battle in time. Longstreet's foraging operations yielded enough food to feed Lee's entire army for two months. However, no further military objective was reached, and the operation caused Longstreet and 15,000 men of the First Corps to be absent from Chancellorsville. Eventually, Longstreet came under criticism from rivals and political enemies claiming that he could have marched his men back from Suffolk in time to join Lee.[143][144][145] However, Sorrel says that it was "humanly impossible" for the men to move any faster.[145]

Gettysburg

| External video | |

|---|---|

Campaign plans

c. 1900

Following Chancellorsville and the death of Stonewall Jackson, Longstreet and Lee met in mid-May to discuss options for the army's summer campaign. Longstreet once more pushed for the detachment of all or part of his corps to be sent to Tennessee. The justification for this course of action was becoming more urgent as Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant was advancing on the critical Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, Vicksburg. Longstreet argued that a reinforced army under Bragg could defeat Rosecrans and drive toward the Ohio River, which would compel Grant to break his hold on Vicksburg.[146] He advanced these views during a meeting with Seddon, who approved of the idea but doubted that Lee would do so, and opined that Davis would be unlikely to go against Lee's wishes. Longstreet had criticized Bragg's generalship and may have been hoping to replace him, although he also might have wished to see Joseph Johnston take command, and indicated that he would be content to serve under him as a corps commander. Lee prevented this by telling Davis that parting with large numbers of troops would force him to move his army closer to Richmond, and instead advanced a plan to invade Pennsylvania. A campaign in the North would relieve agricultural and military pressure that the war was placing on Virginia and North Carolina, and, by threatening a federal city, disrupt Union offensives elsewhere and erode support for the war among Northern civilians.[147] In his memoirs, Longstreet described his reaction to Lee's proposal:

His plan or wishes announced, it became useless and improper to offer suggestions leading to a different course. All that I could ask was that the policy of the campaign should be one of defensive tactics; that we should work so as to force the enemy to attack us, in such good position as we might find in our own country, so well adapted to that purpose—which might assure us of a grand triumph. To this, he readily assented as an important and material adjunct to his general plan.[148]

There is conflicting evidence for the veracity of Longstreet's account. It was written years after the campaign and is affected by hindsight, both of the results of the battle and of heavy postbellum criticism. In letters of the time, Longstreet made no reference to such a bargain with Lee. In April 1868, Lee said that he "had never made any such promise, and had never thought of doing any such thing".[149][150] Yet in his post-battle report, Lee wrote, "It had not been intended to fight a general battle at such a distance from our base, unless attacked by the enemy."[151]

The Army of Northern Virginia was reorganized after Jackson's death. Two division commanders, Richard S. Ewell and A. P. Hill, were promoted to lieutenant general and assumed command of the Second and the newly created Third Corps respectively. Longstreet's First Corps gave up R.H. Anderson's division during the reorganization, leaving Longstreet with the divisions of Hood, McLaws, and Pickett.[152][153]

After determining that an advance north was inevitable, Longstreet dispatched the scout Henry Thomas Harrison, whom he had met during the Suffolk Campaign, to gather information. He paid Harrison in gold and told him that he "did not care to see him till he could bring information of importance".[154] Ewell's corps led the army north, followed by Longstreet's and Hill's. The First Corps crossed the Potomac River from June 25 to June 26.[155] Harrison reported to Longstreet on the evening of June 28 and was instrumental in warning the Confederates that the Army of the Potomac was advancing north to meet them more quickly than they had anticipated, and was already gathered around Frederick, Maryland. Lee was initially skeptical, but the report prompted him to order the immediate concentration of his army north of Frederick near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Harrison also brought news that Hooker had been replaced as commander of the Army of the Potomac by Meade.[156]

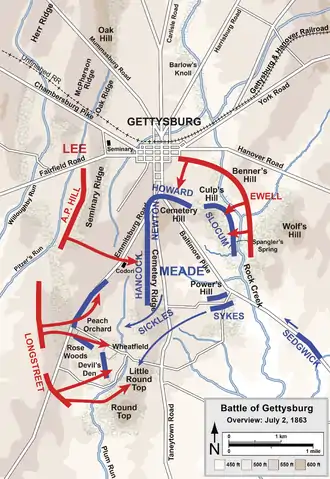

July 1–2

Longstreet's actions at the Battle of Gettysburg would become the centerpiece of lasting controversy.[157] Longstreet arrived on the battlefield at about 4:30 in the afternoon of the first day, July 1, 1863, hours ahead of his troops. Lee had not intended to fight before his army was fully concentrated, but chance and decisions by A.P. Hill, whose troops were the first to be engaged, brought on the confrontation. The battle on the first day was a strong Confederate victory. Two Union corps had been driven by Ewell and Hill from their positions north of Gettysburg back through the town into defensive positions on the heights to the south. Meeting with Lee, Longstreet was concerned about the strength of the Union defensive position on elevated ground and advocated a strategic movement around the left flank of the enemy, to "secure good ground between him and his capital", which would presumably compel Meade to attack defensive positions erected by the Confederates.[158][159][160] Instead, Lee exclaimed, "If the enemy is there tomorrow, I will attack him." Longstreet replied, "If he is there tomorrow it is because he wants you to attack."[161] Lee, energized by the success of his army that day, again refused. Longstreet suggested an immediate assault on the federal positions, but Lee insisted on waiting for Hood and McLaws, who were marching towards Gettysburg on the Chambersburg Pike. Longstreet sent a courier towards them down the Cashtown Road to hurry them along. They eventually bivouacked about four miles (6.4 km) behind the lines. Pickett was performing rearguard duty in Cashtown and would not be ready to move until morning. A major blunder occurred when Ewell failed to seize the heights on Cemetery Hill after being ordered to do so "if practicable" by Lee.[162][163][164]

Lee's plan for July 2 called for Longstreet to attack the Union's left flank, to be followed up by Hill's attack on Cemetery Ridge near the center, while Ewell demonstrated on the Union right. Longstreet again argued for a flanking maneuver around the Union left, but Lee rejected his plan. Longstreet was not ready to attack as early as Lee envisioned. He received permission from Lee to wait for Law's brigade of Hood's division to reach the field before advancing. Law marched his men quickly, covering 28 miles (45 km) in eleven hours, but did not arrive until noon. Three of Longstreet's brigades were still in march column some distance from their designated positions.[165][166] Longstreet's soldiers were forced to take a long detour while approaching the enemy position, misled by inadequate reconnaissance that failed to identify a completely concealed route.[167]

Postbellum criticism of Longstreet claims that he was ordered by Lee to attack in the early morning and that his delays were a significant contributor to the loss of the battle.[117] Early and William N. Pendleton testified that Lee had ordered Longstreet to attack at sunrise and that Longstreet disobeyed. This claim was factually untrue and denied by Lee's staff officers Walter H. Taylor and Charles Marshall.[168] Lee agreed to the delays for arriving troops and did not issue his formal order for the attack until 11 A.M. Longstreet did not aggressively pursue Lee's orders to launch an attack. Sorrel writes that Longstreet, unenthusiastic about the attack, displayed lethargy in bringing his troops forward. While Lee expected an attack around noon, Longstreet was not ready until 4 P.M. Meade used the time to bring more of his troops forward.[169][170][171] Campaign historian Edwin Coddington presents the approach to the federal positions as "a comedy of errors such as one might expect of inexperienced commanders and raw militia, but not of Lee's 'War Horse' and his veteran troops".[172]

Hood opposed an attack on the Union left, arguing that the Union position was too strong, and proposed that his troops be moved to the right near Big Round Top and hit the Union in the rear. Longstreet insisted that Lee had rejected this plan and ordered him to make the assault against the front of the enemy lines.[173][174][175] Once the assault began at around 4 pm, Longstreet pressed McLaws and Hood strongly against heavy Union resistance.[176] Longstreet personally led the attack on horseback. Union Major General Daniel Sickles, commanding the III Corps, had, contrary to Meade's orders, marched his men to the Peach Orchard, an exposed position well in front of the main Union lines. R.H. Anderson's division of Hill's corps, alongside McLaws' division and part of the division of Hood, launched a ferocious assault against Sickles with heavy artillery support which, after extremely intense fighting, pushed his corps back to the main Union lines. The Confederates were eventually repulsed after encountering fierce resistance from Union reinforcements. General Hood was wounded and replaced in command of his division by Law. Brigade commanders Barksdale and Paul Jones Semmes, both under McLaws, were mortally wounded. Law's brigade attempted to carry Little Round Top, a hill on the far left of the Union lines. The hill had originally been without troops before Union Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren, Chief of Engineers, taking advantage of the Confederate delay, sent soldiers from the V Corps to fortify it. Confederate troops took the part of the hill known as Devil's Den, but were unable to drive off Union forces situated at the top of the hill.[177][178][179][180] The attacks had failed, and Longstreet's corps suffered more than 4,000 casualties.[181] Contributing to Longstreet's failure was the fact that his attacks did not occur simultaneously with those of A.P. Hill and Ewell. Large portions of Hill's and Ewell's corps, including soldiers who had seen significant action the day before, were unengaged, and Meade was able to shift Thomas H. Ruger's division from Ewell's front in order to oppose Longstreet.[182]

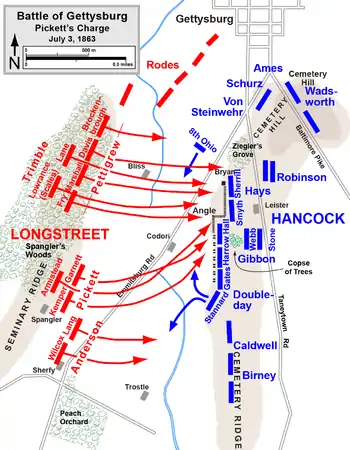

July 3

On the night of July 2, Longstreet did not follow his usual custom of meeting Lee at his headquarters to discuss the day's battle, claiming that he was too fatigued to make the ride. Instead, he spent part of the night planning for a movement around Big Round Top that would allow him to attack the enemy's flank and rear. Longstreet, despite his use of scouting parties, was apparently unaware that a considerable body of troops from the Union VI Corps under John Sedgwick was in position to block this move. Shortly after issuing orders for the attack, around sunrise, Longstreet was joined at his headquarters by Lee, who was dismayed at this turn of events. The commanding general had intended for Longstreet to attack the Union left early in the morning in a manner similar to the attack of July 2, using Pickett's newly arrived division, in concert with a resumed attack by Ewell on Culp's Hill. What Lee found was that no one had ordered Pickett's division forward from its bivouac in the rear and that Longstreet had been planning an independent operation without consulting with him.[183] Lee wrote in his after-battle report that Longstreet's "dispositions were not completed as early as was expected".[151]

Since his plans for an early morning coordinated attack were now infeasible, Lee instead ordered Longstreet to coordinate a massive assault on the center of the Union line at Cemetery Ridge with his corps. The Union position was held by the II Corps under Winfield Scott Hancock. Longstreet strongly felt that this assault had little chance of success, and made known his concerns to Lee.[184] The Confederates would have to march over close to one mile (1.6 km) of open ground and spend time negotiating sturdy fences under fire.[185][186] Longstreet urged Lee not to use his entire corps in the attack, arguing that the divisions of Law and McLaws were tired from the previous day's combat and that shifting them towards Cemetery Ridge would dangerously expose the Confederate right flank. Lee conceded and instead decided to use men from A.P. Hill's corps to accompany Pickett. The force would include about 14,000 or 15,000 men.[185][187] Longstreet again told Lee that he believed the attack would fail.[188]

Lee did not change his mind, and Longstreet relented. The final plan called for an artillery barrage by 170 cannon under Alexander. Then, the three brigades under Pickett and the four brigades in the division of Henry Heth, temporarily commanded by Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew, positioned to Pickett's left, would lead the attack. Two brigades from William Dorsey Pender's division, temporarily commanded by Brigadier General Isaac R. Trimble, would fill in as support behind Pettigrew. Two brigades from R.H. Anderson's division were to support Pickett's right flank. Despite his vocal disapproval of the plan and although most of the units came from A.P. Hill's corps, Lee designated Longstreet to lead the attack. Longstreet dutifully saw to the positioning of Pickett's men. General Pickett placed the brigades of Garnett and Brigadier General James L. Kemper in front with Armistead behind them in support. However, Longstreet neglected to adequately check on Pettigrew's division. Pettigrew had never commanded a division before, and the division which he had just been appointed to lead had suffered one-third casualties in the fighting on July 1. His men were positioned behind Pickett's lines, leaving Pickett vulnerable, and the troops on his far left were dangerously exposed. Longstreet and Hill still had a tense relationship, which may have played a role in Longstreet not carefully overseeing Hill's troops. Hill was with Lee and Longstreet throughout much of the morning, but wrote after the battle that he had ordered his men to report to Longstreet, implying that he felt he was not responsible for arranging them.[189]

During preparations for the attack, Longstreet began to agonize over the assault. He attempted to pass the responsibility for launching Pickett's division to Alexander. The artillery bombardment began at about 1 P.M. Union batteries responded, and the two sides fired back and forth at each other for about one hour and forty minutes. When the time came to actually order Pickett forward, Longstreet could only nod in assent, unable to verbalize the order, thus beginning the assault known as Pickett's Charge. Beginning at about 3 P.M., Confederate troops marched towards the Union positions. As Longstreet had anticipated, the attack was a complete disaster. The Confederates were easily cut down, and the assaulting units suffered massive casualties. Pettigrew and Trimble were wounded. Pickett's first two brigades were severely mauled. Kemper was wounded and Garnett was killed. Armistead's brigade briefly breached the stone wall that marked Hancock's lines, where Armistead fell mortally wounded, but the brigade was repulsed.[190][191][192] To his men, Lee said, "It is all my fault."[193] According to two of Longstreet's staff officers, Lee subsequently expressed regret for not taking Longstreet's advice.[194] On July 4, the Confederate army began its retreat from Gettysburg. Hampered by rain, the bulk of the army finally made it across the Potomac River on the night of July 13–14.[195][196]

Chickamauga

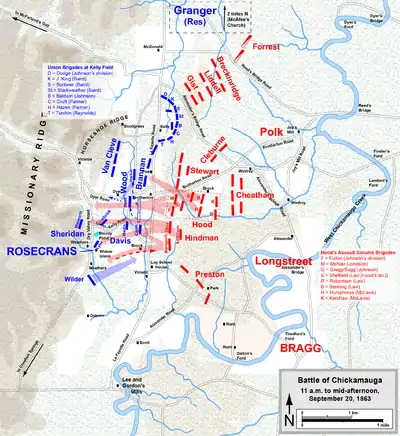

In mid-August 1863, Longstreet once again resumed his attempts to be transferred to the Western Theater. He wrote a private letter to Seddon, requesting that he be transferred to serve under his old friend Joseph Johnston. He followed this up in conversations with his congressional ally Wigfall, who had long considered Longstreet a suitable replacement for Braxton Bragg. Bragg had a poor combat record and was very unpopular with his men and officers. Lee and President Davis agreed to the request on September 5. McLaws, Hood, a brigade from Pickett's division, and Alexander's 26-gun artillery battalion, traveled over 16 railroads on a 775-mile (1,247 km) route through the Carolinas to reach Bragg in northern Georgia.[197] On September 8, with reinforcements on the way, Bragg gave up the fortified city and critical rail juncture of Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Rosecrans without a fight and retreated into Georgia.[198] The troop transfer took over three weeks. Lead elements of the corps arrived on September 17.[199]

On September 19 at the Battle of Chickamauga, Bragg began an unsuccessful attempt to interpose his army between Rosecrans and Chattanooga before the arrival of most of Longstreet's corps. Throughout the day, Confederate troops launched largely ineffectual assaults on Union positions that were highly costly for both sides. One of Longstreet's own divisions under Hood successfully resisted a strong Union counterattack from Jefferson C. Davis's division of the XX Corps that afternoon.[200][201] When Longstreet himself arrived on the field in the late evening, he failed to find Bragg's headquarters. He and his staff spent considerable time riding looking for them. They accidentally came across a federal picket line and were nearly captured.[202][203]

When the two finally met at Bragg's headquarters late at night, Bragg placed Longstreet in command of the left wing of his army; Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk commanded the right. Longstreet's command consisted of Simon Bolivar Buckner's corps, under which were the divisions of Alexander P. Stewart and William Preston, Bushrod Johnson's division, Thomas C. Hindman's division, and Hood's division. McLaws' division fell under Longstreet's command but did not completely arrive from Virginia until September 21, after the Battle of Chickamauga had ended. Joseph B. Kershaw was placed in command of his two brigades which were on the field. Bragg made a plan for an attack at 8 in the morning on September 20. Longstreet lined up most of his men into two lines, but he placed Hood's division behind Johnson in a column, intended as shock troops.[204][205] The attack was supposed to begin early in the morning shortly after an assault by Polk's wing. However, confusion and mishandled orders caused Polk's attack to be delayed, and Longstreet's advance did not begin until just after 11 after hearing gunfire from his left.[206] A mistaken order from General Rosecrans caused a gap to appear in the Union line by transferring Thomas J. Wood's division from the right to reinforce the XIV Corps under George Henry Thomas in the center.[207]

Longstreet took advantage of the confusion to increase his chances of success. The organization of the attack was well suited to the terrain and would have penetrated the Union line regardless. Johnson's division poured through the gap, driving the Union forces back.[208] After Longstreet ordered Hindman's division forward, the Union right entirely collapsed.[209][210] Rosecrans fled the field as units began to retreat in panic. Thomas managed to rally the retreating units and solidify a defensive position on Snodgrass Hill. He held that position against repeated afternoon attacks by Longstreet, who was not adequately supported by the Confederate right wing.[211][212] Sorrel told Stewart to move his division forward to attack the Union rearguard. Stewart initially declined, demanding confirmation from Longstreet. Longstreet was incensed at his refusal and ordered him to go forward. Stewart did so and captured about 400 prisoners, but Thomas had already managed to extricate the units under his control to Chattanooga.[213][214][215] Bragg's failure to coordinate the right wing and cavalry to further envelop Thomas prevented a total rout of the Union Army.[213][216] Bragg also neglected to pursue the retreating Federals aggressively, resulting in the futile Siege of Chattanooga. He had dismissed a proposal from Longstreet that he do so, citing a lack of transportation and calling the plan a "visionary scheme".[213] Nevertheless, Chickamauga was the greatest Confederate victory in the Western Theater and Longstreet received a significant portion of the credit.[217]

Tennessee

Not long after the Confederates entered Tennessee following their victory at Chickamauga, Longstreet clashed with Bragg and became a leader of the group of senior commanders who conspired to have him removed. Bragg's subordinates had long been dissatisfied with his abrasive personality and poor battlefield record; the arrival of Longstreet (the senior lieutenant general in the Army) and his officers, and the fact that they quickly took their side, added credibility to the earlier claims. Longstreet wrote to Seddon, "I am convinced that nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander."[218] The situation became so grave that Davis was forced to intercede in person. What followed was a scene in which Bragg sat red-faced as a procession of his subordinates condemned him. Longstreet stated that Bragg "was incompetent to manage an army or put men into a fight" and that he "knew nothing of the business". On October 12, Davis declared his support for Bragg. He left him and his dissatisfied subordinates in their positions.[219]

Bragg relieved or reassigned the generals who had testified against him and retaliated against Longstreet by reducing his command to only those units that he brought with him from Virginia. Bragg resigned himself to the siege in Chattanooga. At about this time, Longstreet learned of the birth of a son, who was named Robert Lee.[220] Grant arrived in Chattanooga on October 23 and took overall command of the new Union Military Division of the Mississippi. He replaced Rosecrans with Thomas.[221]

While Longstreet's relationship with Bragg was extremely poor, his connections with his subordinates also deteriorated. He had a strong antebellum friendship with McLaws, but it began to show signs of souring after McLaws criticized Longstreet's conduct at Gettysburg and was accused by Longstreet of displaying lethargy after Chickamauga.[222] Hood's old division was under the temporary command of Brigadier General Micah Jenkins. The brigadier general who had been in the division the longest was Evander Law, who had temporarily commanded the division more than once in the past. However, Jenkins outranked Law. Both Jenkins and Law disliked each other and desired permanent command of the division. Longstreet favored Jenkins, his longtime protégé, while most of the men favored Law.[222][223] Longstreet had asked Davis to name a permanent commander, but he refused.[224]

On October 27, Union troops managed to open up a "cracker line" to access food by defeating Law's brigade under Jenkins at the Battle of Brown's Ferry. In the nighttime Battle of Wauhatchie from October 28–29, Jenkins failed to regain the lost position. He blamed Law and Brigadier General Jerome B. Robertson for the lack of success. Longstreet took no immediate action against Law but complained about Robertson. A court of inquiry was set up, but its proceedings were suspended and Robertson returned to command.[225]

After the Confederate failures, Longstreet devised a strategy to prevent reinforcement and a lifting of the siege by Grant. He knew this Union reaction was underway, and that the nearest railhead was Bridgeport, Alabama, where portions of two Union corps would soon arrive. After sending his artillery commander, Porter Alexander, to reconnoiter the Union-occupied town, he devised a plan to shift most of the Army of Tennessee away from the siege, setting up logistical support in Rome, Georgia, to go after Bridgeport to take the railhead, possibly catching Hooker, who was leading a detachment of arriving Union troops from the Eastern Theater, in a disadvantageous position. The plan was well received and approved by President Davis,[226] but it was disapproved by Bragg, who objected to the significant logistical challenges it posed. Longstreet accepted Bragg's arguments and agreed to a plan in which he and his men were dispatched to East Tennessee to deal with an advance by the Union Army of the Ohio, commanded by Burnside. Longstreet was selected both due to enmity on Bragg's part and because the War Department intended for Longstreet's men to return to Lee's army and this movement was in that direction. Thus began the Knoxville campaign.[227][228]

Longstreet was criticized for the slow pace of his advance toward Knoxville in November and some of his soldiers began using the nickname "Peter the Slow" to describe him.[229] At the Battle of Campbell's Station on November 16, the Federals evaded Longstreet's troops. This was due both to the poor performance of Law, who exposed his brigade to the enemy and thus ruined what was supposed to be a surprise attack, and Burnside's skillful retreat. The Confederates also dealt with muddy roads and a shortage of good supplies.[230]

Burnside settled into entrenchments around the city, which Longstreet besieged. Longstreet soon learned that Bragg had been defeated at Chattanooga on November 25 and that Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's men were marching to relieve Burnside. He decided to risk a frontal attack on Union entrenchments before they arrived. On November 29, he sent his troops forward at the Battle of Fort Sanders. The attack was repulsed, and Longstreet was forced to retreat.[231] When Bragg was defeated by Grant, Longstreet was ordered to join forces with the Army of Tennessee in northern Georgia. He demurred and began to move back to Virginia, soon pursued by Sherman. Longstreet defeated federal troops in an engagement at Bean's Station on December 14 before the armies went into winter quarters. The greatest effect of the campaign was to deprive Bragg of troops he sorely needed in Chattanooga. Longstreet's second independent command (after Suffolk) was a failure and his self-confidence was damaged. He reacted to the failure of the campaign by blaming others. He relieved Lafayette McLaws from command and requested the court-martial of Robertson and Law. He also submitted a letter of resignation to Adjutant General Samuel Cooper on December 30, 1863, but his request to be relieved was denied.[232][233] Bragg, meanwhile, was relieved from command and replaced by Joseph Johnston on December 27.[234]

The sufferings of the Confederate troops continued into the winter. Longstreet established his headquarters in Rogersville. He attempted to keep communications open with Lee's army in Virginia, but Federal cavalry Brigadier General William W. Averell's raids destroyed the railroads, isolating him and forcing him to rely only on Eastern Tennessee for supplies. Longstreet's corps suffered through a severe winter in Eastern Tennessee with inadequate shelter and provisions. More than half of the men were without shoes.[235] Writing to Georgia's Quartermaster General, Ira Roe Foster on January 24, 1864, Longstreet noted: "There are five Georgia Brigades in this Army – Wofford's, G.T. Anderson's, Bryan's, Benning's, and Crews' cavalry brigade. They are all alike in excessive need of shoes, clothing of all kinds, and blankets. All that you can send will be thankfully received."[236]

In February 1864, the lines of communication were repaired. Once the weather warmed, Longstreet's men marched north and returned to the Army of Northern Virginia at Gordonsville.[235]

Wilderness to Appomattox

In March, Longstreet rejoined the Army of Northern Virginia. Presented by Lee with a plan for a joint offensive by Johnston and Longstreet into Kentucky, Longstreet made the scheme bolder by adding 20,000 men under General Beauregard, who was headquartered in South Carolina. The plan failed to be enacted as it met with disapproval from President Davis and his newly appointed military advisor, Braxton Bragg, and Longstreet remained in Virginia.[237][238]

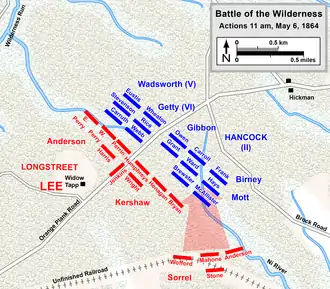

Longstreet discovered that his old friend Ulysses S. Grant had been appointed General-in-Chief of the Union Army, with headquarters in the field alongside the Army of the Potomac. Longstreet told his fellow officers that "he will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war."[239] Longstreet helped save the Confederate Army from defeat in his first battle back with Lee's army, the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864.[240] After Grant moved south of the Rapidan River in an attempt to take Richmond, Lee intended to delay battle in order to give Longstreet's 14,000 men time to arrive on the field. Grant disrupted these plans by attacking him on May 5, and the fighting was inconclusive. The following morning at 5 am, Hancock led two divisions in a ferocious attack on A.P. Hill's corps, driving the men back two miles (3.2 km). Just as this was happening, Longstreet's men arrived on the field. They took advantage of an old roadbed built for an out-of-use railroad to creep through a densely wooded area unnoticed before launching a powerful flanking attack.[241]

Longstreet's men moved forward along the Orange Plank Road against the II Corps and in two hours nearly drove it from the field. He developed tactics to deal with difficult terrain, ordering the advance of six brigades by heavy skirmish lines, which allowed his men to deliver a continuous fire into the enemy while proving to be elusive targets themselves. Historian Edward Steere attributed much of the success of the Army to "the display of tactical genius by Longstreet which more than redressed his disparity in numerical strength".[242] After the war, Hancock said to Longstreet of this flanking maneuver: "You rolled me up like a wet blanket."[243]