John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (/ˈsɑːrdʒənt/; January 12, 1856 – April 14, 1925)[1] was an American expatriate artist, considered the "leading portrait painter of his generation" for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury.[2][3] He created roughly 900 oil paintings and more than 2,000 watercolors, as well as countless sketches and charcoal drawings. His oeuvre documents worldwide travel, from Venice to the Tyrol, Corfu, Spain, the Middle East, Montana, Maine, and Florida.

John Singer Sargent | |

|---|---|

Sargent photographed by James E. Purdy in 1903 | |

| Born | January 12, 1856 |

| Died | April 14, 1925 (aged 69) London, England |

| Resting place | Brookwood Cemetery 51°17′52″N 0°37′29″W |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Portrait of Madame X El Jaleo The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose Lady Agnew of Lochnaw |

| Movement | Impressionism |

Born in Florence to American parents, he was trained in Paris before moving to London, living most of his life in Europe. He enjoyed international acclaim as a portrait painter. An early submission to the Paris Salon in the 1880s, his Portrait of Madame X, was intended to consolidate his position as a society painter in Paris, but instead resulted in scandal. During the next year following the scandal, Sargent departed for England where he continued a successful career as a portrait artist.

From the beginning, Sargent's work is characterized by remarkable technical facility, particularly in his ability to draw with a brush, which in later years inspired admiration as well as criticism for a supposed superficiality. His commissioned works were consistent with the grand manner of portraiture, while his informal studies and landscape paintings displayed a familiarity with Impressionism. In later life Sargent expressed ambivalence about the restrictions of formal portrait work, and devoted much of his energy to mural painting and working en plein air. Art historians generally ignored society artists such as Sargent until the late 20th century.[4]

The exhibition in the 1980s of Sargent's previously hidden male nudes served to spark a re-evaluation of his life and work, and its psychological complexity. In addition to the beauty, sensation, and innovation of his oeuvre, his same-sex interests, unconventional friendships with women, and engagement with race, gender-nonconformity and emerging globalism, are now viewed as socially and aesthetically progressive, and radical.[5]

Early life

Sargent is a descendant of Epes Sargent, a colonial military leader and jurist. Before John Singer Sargent's birth, his father, FitzWilliam (b. 1820 Gloucester, Massachusetts), was an eye surgeon at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia 1844–1854. After John's older sister died at the age of two, his mother, Mary Newbold Singer (née Singer, 1826–1906), suffered a breakdown, and the couple decided to go abroad to recover.[1] They remained nomadic expatriates for the rest of their lives.[6][7] Although based in Paris, Sargent's parents moved regularly with the seasons to the sea and the mountain resorts in France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland.

While Mary was pregnant, they stopped in Florence, Tuscany, because of a cholera epidemic. Sargent was born there in 1856. A year later, his sister Mary was born. After her birth, FitzWilliam reluctantly resigned his post in Philadelphia and accepted his wife's request to remain abroad.[8] They lived modestly on a small inheritance and savings, leading a quiet life with their children. They generally avoided society and other Americans except for friends in the art world.[9] Four more children were born abroad, of whom only two lived past childhood.[10]

Although his father was a patient teacher of basic subjects, young Sargent was a rambunctious child, more interested in outdoor activities than his studies. As his father wrote home, "He is quite a close observer of animated nature."[11] His mother was convinced that traveling around Europe, and visiting museums and churches, would give young Sargent a satisfactory education. Several attempts to have him formally schooled failed, owing mostly to their itinerant life. His mother was a capable amateur artist and his father was a skilled medical illustrator.[12] Early on, she gave him sketchbooks and encouraged drawing excursions. Sargent worked on his drawings, and he enthusiastically copied images from The Illustrated London News of ships and made detailed sketches of landscapes.[13] FitzWilliam had hoped that his son's interest in ships and the sea might lead him toward a naval career.

At thirteen, his mother reported that John "sketches quite nicely, & has a remarkably quick and correct eye. If we could afford to give him really good lessons, he would soon be quite a little artist."[14] At the age of thirteen, he received some watercolor lessons from Carl Welsch, a German landscape painter.[15] Although his education was far from complete, Sargent grew up to be a highly literate and cosmopolitan young man, accomplished in art, music, and literature.[16] He was fluent in English, French, Italian, and German. At seventeen, Sargent was described as "willful, curious, determined and strong" (after his mother) yet shy, generous, and modest (after his father).[17] He was well-acquainted with many of the great masters from first hand observation, as he wrote in 1874, "I have learned in Venice to admire Tintoretto immensely and to consider him perhaps second only to Michelangelo and Titian."[18]

Training

.jpg.webp)

An attempt to study at the Academy of Florence failed, as the school was re-organizing at the time. After returning to Paris from Florence Sargent began his art studies with the young French portraitist Carolus-Duran. Following a meteoric rise, the artist was noted for his bold technique and modern teaching methods; his influence would be pivotal to Sargent during the period from 1874 to 1878.[19]

In 1874 Sargent passed on his first attempt the rigorous exam required to gain admission to the École des Beaux-Arts, the premier art school in France. He took drawing classes, which included anatomy and perspective, and gained a silver prize.[19][20] He also spent much time in self-study, drawing in museums and painting in a studio he shared with James Carroll Beckwith. He became both a valuable friend and Sargent's primary connection with the American artists abroad.[21] Sargent also took some lessons from Léon Bonnat.[20]

Carolus-Duran's atelier was progressive, dispensing with the traditional academic approach, which required careful drawing and underpainting, in favor of the alla prima method of working directly on the canvas with a loaded brush, derived from Diego Velázquez. It was an approach that relied on the proper placement of tones of paint. Sargent would later create an art piece in this style that prompted comments such as: "The student has surpassed the teacher."[22]

This approach also permitted spontaneous flourishes of color not bound to an under-drawing. It was markedly different from the traditional atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme, where Americans Thomas Eakins and Julian Alden Weir had studied. Sargent was the star student in short order. Weir met Sargent in 1874 and noted that Sargent was "one of the most talented fellows I have ever come across; his drawings are like the old masters, and his color is equally fine."[21] Sargent's excellent command of French and his superior talent made him both popular and admired. Through his friendship with Paul César Helleu, Sargent would meet giants of the art world, including Degas, Rodin, Monet, and Whistler.

Sargent's early enthusiasm was for landscapes, not portraiture, as evidenced by his voluminous sketches full of mountains, seascapes, and buildings.[23] Carolus-Duran's expertise in portraiture finally influenced Sargent in that direction. Commissions for history paintings were still considered more prestigious, but were much harder to get. Portrait painting, on the other hand, was the best way of promoting an art career, getting exhibited in the Salon, and gaining commissions to earn a livelihood.

Sargent's first major portrait was of his friend Fanny Watts in 1877, and was also his first Salon admission. Its particularly well-executed pose drew attention.[23] His second salon entry was the Oyster Gatherers of Cançale, an impressionistic painting of which he made two copies, one of which he sent back to the United States, and both received warm reviews.[24]

Early career

In 1879, at the age of 23, Sargent painted a portrait of teacher Carolus-Duran; the virtuoso effort met with public approval and announced the direction his mature work would take. Its showing at the Paris Salon was both a tribute to his teacher and an advertisement for portrait commissions.[25] Of Sargent's early work, Henry James wrote that the artist offered "the slightly 'uncanny' spectacle of a talent which on the very threshold of its career has nothing more to learn."[26]

After leaving Carolus-Duran's atelier, Sargent visited Spain. There he studied the paintings of Velázquez with a passion, absorbing the master's technique, and in his travels gathered ideas for future works.[27] He was entranced with Spanish music and dance. The trip also re-awakened his own talent for music (which was nearly equal to his artistic talent), and which found visual expression in his early masterpiece El Jaleo (1882). Music would continue to play a major part in his social life as well, as he was a skillful accompanist of both amateur and professional musicians. Sargent became a strong advocate for modern composers, especially Gabriel Fauré.[28] Trips to Italy provided sketches and ideas for several Venetian street scenes genre paintings, which effectively captured gestures and postures he would find useful in later portraiture.[29]

Upon his return to Paris, Sargent quickly received several portrait commissions. His career was launched. He immediately demonstrated the concentration and stamina that enabled him to paint with workman-like steadiness for the next twenty-five years. He filled in the gaps between commissions with many non-commissioned portraits of friends and colleagues. His fine manners, perfect French, and great skill made him a standout among the newer portraitists, and his fame quickly spread. He confidently set high prices and turned down unsatisfactory sitters.[30] He mentored his friend Emil Fuchs who was learning to paint portraits in oils.[31]

Works

Nineteenth-century portraits

In the early 1880s, Sargent regularly exhibited portraits at the Salon, and these were mostly full-length portrayals of women, such as Madame Edouard Pailleron (1880) (done en plein-air) and Madame Ramón Subercaseaux (1881). He continued to receive positive critical notice.[32]

Sargent's best portraits reveal the individuality and personality of the sitters; his most ardent admirers think he is matched in this only by Velázquez, who was one of Sargent's great influences. The Spanish master's spell is apparent in Sargent's The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882, a haunting interior that echoes Velázquez's Las Meninas.[33] As in many of his early portraits, Sargent confidently tries different approaches with each new challenge, here employing both unusual composition and lighting to striking effect. One of his most widely exhibited and best loved works of the 1880s was The Lady with the Rose (1882), a portrait of Charlotte Burckhardt, a close friend and possible romantic attachment.[34]

%252C_John_Singer_Sargent%252C_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg.webp)

His most controversial work, Portrait of Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) (1884) is now considered one of his best works, and was the artist's personal favorite; he stated in 1915, "I suppose it is the best thing I have done."[35] When unveiled in Paris at the 1884 Salon, it aroused such a negative reaction that it likely prompted Sargent's move to London. Sargent's self-confidence had led him to attempt a risque experiment in portraiture—but this time it unexpectedly backfired.[36] The painting was not commissioned by her, and he pursued her for the opportunity, quite unlike most of his portrait work where clients sought him out. Sargent wrote to a common acquaintance:

I have a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty. ...you might tell her that I am a man of prodigious talent.[37]

It took well over a year to complete the painting.[38] The first version of the portrait of Madame Gautreau, with the famously plunging neckline, white-powdered skin, and arrogantly cocked head, featured an intentionally suggestive off-the-shoulder dress strap, on her right side only, which made the overall effect more daring and sensual.[39] Sargent repainted the strap to its expected over-the-shoulder position to try to dampen the furor, but the damage had been done. French commissions dried up and he told his friend Edmund Gosse in 1885 that he contemplated giving up painting for music or business.[40]

Writing of the reaction of visitors, Judith Gautier observed:

Is it a woman? a chimera, the figure of a unicorn rearing as on a heraldic coat of arms or perhaps the work of some oriental decorative artist to whom the human form is forbidden and who, wishing to be reminded of woman, has drawn the delicious arabesque? No, it is none of these things, but rather the precise image of a modern woman scrupulously drawn by a painter who is a master of his art."[41]

Prior to the Madame X scandal of 1884, Sargent had painted exotic beauties such as Rosina Ferrara of Capri, and the Spanish expatriate model Carmela Bertagna, but the earlier pictures had not been intended for broad public reception. Sargent kept the painting prominently displayed in his London studio until he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916 after moving to the United States, and a few months after Gautreau's death.

Before arriving in England, Sargent began sending paintings for exhibition at the Royal Academy. These included the portraits of Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881), a flamboyant essay in red and his first full-length male portrait, and the more traditional Mrs. Henry White (1883). The ensuing portrait commissions encouraged Sargent to complete his move to London in 1886. Notwithstanding the Madame X scandal, he had considered moving to London as early as 1882; he had been urged to do so repeatedly by his new friend, the novelist Henry James. In retrospect his transfer to London may be seen to have been inevitable.[42]

English critics were not warm at first, faulting Sargent for his "clever" "Frenchified" handling of paint. One reviewer seeing his portrait of Mrs. Henry White described his technique as "hard" and "almost metallic" with "no taste in expression, air, or modeling." With help from Mrs. White, however, Sargent soon gained the admiration of English patrons and critics.[43] Henry James also gave the artist "a push to the best of my ability."[44]

Sargent spent much time painting outdoors in the English countryside when not in his studio. On a visit to Monet at Giverny in 1885, Sargent painted one of his most Impressionistic portraits, of Monet at work painting outdoors with his new bride nearby. Sargent is usually not thought of as an Impressionist painter, but he sometimes used impressionistic techniques to great effect. His Claude Monet Painting at the Edge of a Wood is rendered in his own version of the Impressionist style. In the 1880s, he attended the Impressionist exhibitions and he began to paint outdoors in the plein-air manner after that visit to Monet. Sargent purchased four Monet works for his personal collection during that time.[45]

Sargent was similarly inspired to do a portrait of his artist friend Paul César Helleu, also painting outdoors with his wife by his side. A photograph very similar to the painting suggests that Sargent occasionally used photography as an aid to composition.[46] Through Helleu, Sargent met and painted the famed French sculptor Auguste Rodin in 1884, a rather somber portrait reminiscent of works by Thomas Eakins.[47] Although the British critics classified Sargent in the Impressionist camp, the French Impressionists thought otherwise. As Monet later stated, "He is not an Impressionist in the sense that we use the word, he is too much under the influence of Carolus-Duran."[48]

Sargent's first major success at the Royal Academy came in 1887, with the enthusiastic response to Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, a large piece, painted on site, of two young girls lighting lanterns in an English garden in Broadway in the Cotswolds. The painting was immediately purchased by the Tate Gallery.

His first trip to New York and Boston as a professional artist in 1887–88 produced over 20 important commissions, including portraits of Isabella Stewart Gardner, the famed Boston art patron. His portrait of Mrs. Adrian Iselin, wife of a New York businessman, revealed her character in one of his most insightful works. In Boston, Sargent was honored with his first solo exhibition, which presented 22 of his paintings.[49] Here he became friends with painter Dennis Miller Bunker, who traveled to England in the summer of 1888 to paint with him en plein air, and is the subject of Sargent's 1888 painting Dennis Miller Bunker Painting at Calcot.

Back in London, Sargent was quickly busy again. His working methods were by then well-established, following many of the steps employed by other master portrait painters before him. After securing a commission through negotiations which he carried out, Sargent would visit the client's home to see where the painting was to hang. He would often review a client's wardrobe to pick suitable attire. Some portraits were done in the client's home, but more often in his studio, which was well-stocked with furniture and background materials he chose for proper effect.[50] He usually required eight to ten sittings from his clients, although he would try to capture the face in one sitting. He usually kept up pleasant conversation and sometimes he would take a break and play the piano for his sitter. Sargent seldom used pencil or oil sketches, and instead laid down oil paint directly.[51] Finally, he would select an appropriate frame.

Sargent had no assistants; he handled all the tasks, such as preparing his canvases, varnishing the painting, arranging for photography, shipping, and documentation. He commanded about $5,000 per portrait, or about $130,000 in current dollars.[52] Some American clients traveled to London at their own expense to have Sargent paint their portrait.

Around 1890, Sargent painted two daring non-commissioned portraits as show pieces—one of actress Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth and one of the popular Spanish dancer La Carmencita.[53] Sargent was elected an associate of the Royal Academy, and was made a full member three years later. In the 1890s, he averaged fourteen portrait commissions per year, none more beautiful than the genteel Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, 1892. His portrait of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley (Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, 1892) was equally well received for its lively depiction of one of London's most notable hostesses. As a portrait painter in the grand manner, Sargent had unmatched success; he portrayed subjects who were at once ennobled and often possessed of nervous energy. Sargent was referred to as "the Van Dyck of our times."[54] Although Sargent was an American expatriate, he returned to the United States many times, often to answer the demand for commissioned portraits.

Sargent exhibited nine of his portraits in the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[55]

Sargent painted a series of three portraits of Robert Louis Stevenson. The second, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson and his Wife (1885), was one of his best known.[56] He also completed portraits of two U.S. presidents: Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

Asher Wertheimer, a wealthy Jewish art dealer living in London, commissioned from Sargent a series of a dozen portraits of his family, the artist's largest commission from a single patron.[57] The Wertheimer portraits reveal a pleasant familiarity between the artist and his subjects. Wertheimer bequeathed most of the paintings to the National Gallery.[58] In 1888, Sargent released his portrait of Alice Vanderbilt Shepard, great-granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt.[59] Many of his most important works are in museums in the United States. In 1897, a friend sponsored a famous portrait in oil of Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, by Sargent, as a wedding gift.[60][61]

Twentieth century portraits

By 1900, Sargent was at the height of his fame. Cartoonist Max Beerbohm completed one of his seventeen caricatures of Sargent, making well known to the public the artist's paunchy physique.[62][63] Although only in his forties, Sargent began to travel more and to devote relatively less time to portrait painting. His An Interior in Venice (1900), a portrait of four members of the Curtis family in their elegant palatial home, Palazzo Barbaro, was a resounding success. But, Whistler did not approve of the looseness of Sargent's brushwork, which he summed up as "smudge everywhere."[64] One of Sargent's last major portraits in his bravura style was that of Lord Ribblesdale, in 1902, finely attired in an elegant hunting uniform. Between 1900 and 1907, Sargent continued his high productivity, which included, in addition to dozens of oil portraits, hundreds of portrait drawings at about $400 each.[65]

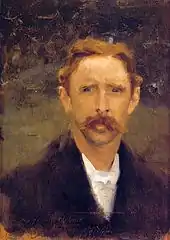

In 1907, at the age of fifty-one, Sargent officially closed his studio. Relieved, he stated, "Painting a portrait would be quite amusing if one were not forced to talk while working…What a nuisance having to entertain the sitter and to look happy when one feels wretched."[66] In that same year, Sargent painted his modest and serious self-portrait, his last, for the celebrated self-portrait collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.[67]

Sargent made several summer visits to the Swiss Alps with his sisters Emily and Violet (Mrs Ormond) and Violet's daughters Rose-Marie and Reine, who were the subject of a number of paintings 1906–1913.[68]

As Sargent wearied of portraiture he pursued architectural and landscapes subjects. During a visit to Rome in 1906 Sargent made an oil painting and several pencil sketches of the exterior staircase and balustrade in front of the Church of Saints Dominic and Sixtus, now the church of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum. The double staircase built in 1654 is the design of architect and sculptor Orazio Torriani (fl.1602–1657). In 1907 he wrote: "I did in Rome a study of a magnificent curved staircase and balustrade, leading to a grand facade that would reduce a millionaire to a worm...."[69] The painting now hangs at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University and the pencil sketches are in the collection of the Harvard University art collection of the Fogg Museum.[70] Sargent later used the architectural features of this stair and balustrade in a portrait of Charles William Eliot, President of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909.[71]

Sargent's fame was still considerable and museums eagerly bought his works. That year he declined a knighthood and decided instead to keep his American citizenship. From 1907[72] on, Sargent largely forsook portrait painting and focused on landscapes. He made numerous visits to the United States in the last decade of his life, including a stay of two full years from 1915 to 1917.[73] In April 1917 Sargent was visiting the Miami estate of James Deering and was invited to cruise the Florida Keys with James and his brother Charles Deering aboard James' yacht Nepenthe. Sargent was much more interested in the "mine of sketching" that was the estate, not at all interested in fishing, and made the cruise "reluctantly," doing some watercolor sketches (including Derelicts, 1917).[74]

By the time Sargent finished his portrait of John D. Rockefeller in 1917, most critics began to consign him to the masters of the past, "a brilliant ambassador between his patrons and posterity." Modernists treated him more harshly, considering him completely out of touch with the reality of American life and with emerging artistic trends including Cubism and Futurism.[75] Sargent quietly accepted the criticism, but refused to alter his negative opinions of modern art. He retorted, "Ingres, Raphael and El Greco, these are now my admirations, these are what I like."[76] In 1925, shortly before he died, Sargent painted his last oil portrait, a canvas of Grace Curzon, Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston. The painting was purchased in 1936 by the Currier Museum of Art, where it is on display.[77]

Watercolors

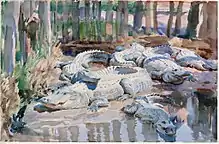

During Sargent's long career, he painted more than 2,000 watercolors, roving from the English countryside to Venice to the Tyrol, Corfu, the Middle East, Montana, Maine, and Florida. Each destination offered pictorial stimulation and treasure. Even at his leisure, in escaping the pressures of the portrait studio, he painted with restless intensity, often painting from morning until night.

His hundreds of watercolors of Venice are especially notable, many done from the perspective of a gondola. His colors were sometimes extremely vivid and as one reviewer noted, "Everything is given with the intensity of a dream."[78] In the Middle East and North Africa Sargent painted Bedouins, goatherds, and fisherman. In the last decade of his life, he produced many watercolors in Maine, Florida, and in the American West, of fauna, flora, and native peoples.

With his watercolors, Sargent was able to indulge his earliest artistic inclinations for nature, architecture, exotic peoples, and noble mountain landscapes. And it is in some of his late works where one senses Sargent painting most purely for himself. His watercolors were executed with a joyful fluidness. He also painted extensively family, friends, gardens, and fountains. In watercolors, he playfully portrayed his friends and family dressed in Orientalist costume, relaxing in brightly lit landscapes that allowed for a more vivid palette and experimental handling than did his commissions (The Chess Game, 1906).[79] His first major solo exhibit of watercolor works was at the Carfax Gallery in London in 1905.[80] In 1909, he exhibited eighty-six watercolors in New York City, eighty-three of which were bought by the Brooklyn Museum.[81] Evan Charteris wrote in 1927:

To live with Sargent's water-colours is to live with sunshine captured and held, with the luster of a bright and legible world, 'the refluent shade' and 'the Ambient ardours of the noon.'[82]

Although not generally accorded the critical respect given Winslow Homer, perhaps America's greatest watercolorist, scholarship has revealed that Sargent was fluent in the entire range of opaque and transparent watercolor technique, including the methods used by Homer.[83]

Other work

As a concession to the insatiable demand of wealthy patrons for portraits, Sargent dashed off hundreds of rapid charcoal portrait sketches, which he called "Mugs". Forty-six of these, spanning the years 1890–1916, were exhibited at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters in 1916.[85]

All of Sargent's murals are to be found in the Boston/Cambridge area. They are in the Boston Public Library, the Museum of Fine Arts, and Harvard's Widener Library. Sargent's largest scale works are the mural decorations that grace the Boston Public Library depicting the history of religion and the gods of polytheism.[86] They were attached to the walls of the library by means of marouflage. He worked on the cycle for almost thirty years but never completed the final mural. Sargent drew on his extensive travels and museum visits to create a dense art historical melange. The murals were restored in 2003–2004.[87]

Sargent worked on the murals from 1895 through 1919; they were intended to show religion's (and society's) progress, from pagan superstition up through the ascension of Christianity, concluding with a painting depicting Jesus delivering the Sermon on the Mount. But Sargent's paintings of "The Church" and "The Synagogue", installed in late 1919, inspired a debate about whether the artist had represented Judaism in a stereotypical, or even an anti-Semitic, manner.[88] Drawing upon iconography that was used in medieval paintings, Sargent portrayed Judaism and the synagogue as a blind, ugly hag, and Christianity and the church as a lovely, radiant young woman. He also failed to understand how these representations might be problematic for the Jews of Boston; he was both surprised and hurt when the paintings were criticized.[89] The paintings were objectionable to Boston Jews since they seemed to show Judaism defeated, and Christianity triumphant.[90] The Boston newspapers also followed the controversy, noting that while many found the paintings offensive, not everyone was in agreement. In the end, Sargent abandoned his plan to finish the murals, and the controversy eventually died down.

Upon his return to England in 1918 after a visit to the United States, Sargent was commissioned as a war artist by the British Ministry of Information. In his large painting Gassed and in many watercolors, he depicted scenes from the Great War.[91] Sargent had been affected by the death of his niece Rose-Marie in the shelling of the St Gervais church, Paris, on Good Friday 1918.[68]

Relationships and personal life

Sargent was a lifelong bachelor with a wide circle of friends including both men and women such as Oscar Wilde (whom he was neighbors with for several years),[92] lesbian author Violet Paget,[93] and his likely lover Albert de Belleroche. Biographers once portrayed him as staid and reticent.[94] However, recent scholarship has theorised he was a private, complex, and passionate man whose homosexual identity was integral to shaping his art.[95][96] This view is based on statements by his friends and associations, the overall alluring remoteness of his portraits, the way his works challenge 19th-century notions of gender difference,[97] his previously ignored male nudes, and some nude male portraits, including those of Thomas E. McKeller, Bartholomy Maganosco, Olimpio Fusco,[98] and that of aristocratic artist Albert de Belleroche, which hung in his Chelsea dining room.[99][100] Sargent had a long friendship with Belleroche, whom he met in 1882 and traveled with frequently. A surviving drawing suggests Sargent might have used him as a model for Madame X, following a coincidence of dates for Sargent drawing each of them separately around the same time,[101] and the delicate pose suggestive more of Sargent's sketches of the male form than his often stiff commissions.

It has been suggested that Sargent's reputation in the 1890s as "the painter of the Jews" may have been due to his empathy with, and complicit enjoyment of their mutual social otherness.[95] One such Jewish client, Betty Wertheimer, wrote that when in Venice, Sargent "was only interested in the Venetian gondoliers".[95][102] The painter Jacques-Émile Blanche, who was one of his early sitters, said after Sargent's death that his sex life "was notorious in Paris, and in Venice, positively scandalous. He was a frenzied bugger."[103]

There were many relationships with women: it has been suggested that those with his sitters Rosina Ferrara, Virginie Gautreau, and Judith Gautier may have tipped into infatuation.[104] As a young man, Sargent also courted for a time Louise Burkhardt, the model for Lady with the Rose.[105]

Sargent's friends and supporters included Henry James, Isabella Stewart Gardner (who commissioned and purchased works from Sargent and sought his advice on other acquisitions),[106] Edward VII,[107] and Paul César Helleu. His associations also included Prince Edmond de Polignac and Count Robert de Montesquiou. Other artists Sargent associated with were Dennis Miller Bunker, James Carroll Beckwith, Edwin Austin Abbey and John Elliott (who also worked on the Boston Public Library murals), Francis David Millet, Joaquín Sorolla and Claude Monet, whom Sargent painted. Between 1905 and 1914, Sargent's frequent traveling companions were the married artist couple Wilfrid de Glehn and Jane Emmet de Glehn. The trio would often spend summers in France, Spain, or Italy, and all three would depict one another in their paintings during their travels.[108]

Albert de Belleroche c. 1882

Albert de Belleroche c. 1882 Man Standing, Hands on Head in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. 1890–1910

Man Standing, Hands on Head in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. 1890–1910 Rosina, 1878, depicting Rosina Ferrara

Rosina, 1878, depicting Rosina Ferrara

Critical assessment

In a time when the art world focused, in turn, on Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, Sargent practiced his own form of Realism, which made brilliant references to Velázquez, Van Dyck, and Gainsborough. His seemingly effortless facility for paraphrasing the masters in a contemporary fashion led to a stream of commissioned portraits of remarkable virtuosity (Arsène Vigeant, 1885, Musées de Metz; Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Newton Phelps-Stokes, 1897, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and earned Sargent the moniker, "the Van Dyck of our times."[109]

Still, during his life his work engendered negative responses from some of his colleagues: Camille Pissarro wrote "he is not an enthusiast but rather an adroit performer,"[110] and Walter Sickert published a satirical turn under the heading "Sargentolatry."[81] By the time of his death he was dismissed as an anachronism, a relic of the Gilded Age and out of step with the artistic sentiments of post-World War I Europe. Elizabeth Prettejohn suggests that the decline of Sargent's reputation was due partly to the rise of anti-Semitism, and the resultant intolerance of 'celebrations of Jewish prosperity.'[111] It has been suggested that the exotic qualities[112] inherent in his work appealed to the sympathies of the Jewish clients whom he painted from the 1890s on.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in his portrait Almina, Daughter of Asher Wertheimer (1908), in which the subject is seen wearing a Persian costume, a pearl encrusted turban, and strumming an Indian tambura, accoutrements all meant to convey sensuality and mystery. If Sargent used this portrait to explore issues of sexuality and identity, it seems to have met with the satisfaction of the subject's father, Asher Wertheimer, a wealthy Jewish art dealer.[57]

Foremost of Sargent's detractors was the influential English art critic Roger Fry, of the Bloomsbury Group, who at the 1926 Sargent retrospective in London dismissed Sargent's work as lacking aesthetic quality: "Wonderful indeed, but most wonderful that this wonderful performance should ever have been confused with that of an artist."[111] And, in the 1930s, Lewis Mumford led a chorus of the severest critics: "Sargent remained to the end an illustrator ... the most adroit appearance of workmanship, the most dashing eye for effect, cannot conceal the essential emptiness of Sargent's mind, or the contemptuous and cynical superficiality of a certain part of his execution."

Part of Sargent's devaluation is also attributed to his expatriate life, which made him seem less American at a time when "authentic" socially conscious American art, as exemplified by the Stieglitz circle and by the Ashcan School, was on the ascent.[113]

After such a long period of critical disfavor, Sargent's reputation has increased steadily since the 1950s.[4] In the 1960s, a revival of Victorian art and new scholarship directed at Sargent strengthened his reputation.[114] Sargent has been the subject of large-scale exhibitions in major museums, including a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1986, and a major 1999 traveling show that exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art Washington, and the National Gallery, London.

In 1986, Andy Warhol commented to Sargent scholar Trevor Fairbrother that Sargent "made everybody look glamorous. Taller. Thinner. But they all have mood, every one of them has a different mood."[115][116] In a TIME magazine article from the 1980s, critic Robert Hughes praised Sargent as "the unrivaled recorder of male power and female beauty in a day that, like ours, paid excessive court to both."[117]

Later life

In 1922 Sargent co-founded New York City's Grand Central Art Galleries together with Edmund Greacen, Walter Leighton Clark, and others.[118] Sargent actively participated in the Grand Central Art Galleries and their academy, the Grand Central School of Art, until his death in 1925. The Galleries held a major retrospective exhibit of Sargent's work in 1924.[119] He then returned to England, where he died at his Chelsea home on April 14, 1925, of heart disease.[119] Sargent is interred in Brookwood Cemetery near Woking, Surrey.[120]

Memorial exhibitions of Sargent's work were held in Boston in 1925, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and at the Royal Academy and Tate Gallery in London in 1926.[121] The Grand Central Art Galleries also organized a posthumous exhibition in 1928 of previously unseen sketches and drawings from throughout his career.[122]

Sales

Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson and his Wife was sold in 2004 for US$8.8 million[123] and is located at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art at Bentonville, Arkansas.

In December 2004, Group with Parasols (A Siesta) (1905) sold for US$23.5 million, nearly double the Sotheby's estimate of $12 million. The previous highest price for a Sargent painting was US$11 million.[124]

In popular culture

In 2018, Comedy Central star Jade Esteban Estrada wrote, directed and starred in Madame X: A Burlesque Fantasy, a story based on the life of Sargent and his famous painting, Portrait of Madame X.[125]

The works of Sargent feature prominently in Maggie Stiefvater's 2021 novel Mister Impossible.

Citations

- "John Singer Sargent". Biography.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- "While his art matched to the spirit of the age, Sargent came into his own in the 1890s as the leading portrait painter of his generation". Ormond, p. 34, 1998.

- "At the time of the Wertheimer commission Sargent was the most celebrated, sought-after and expensive portrait painter in the world". New Orleans Museum of Art Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Schulze, Franz (1980). "J. S. Sargent, Partly Great". Art in America. Vol. 68, no. 2. pp. 90–96.

- Fisher, Paul The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent In His World, Farrar, Straus and Giroux; New York 2022, p9.

- Olson, Stanley (1986). John Singer Sargent: His Portrait. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-312-44456-7.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Olson, p. 2.

- Olson, p. 4.

- Fairbrother, Trevor (1994). John Singer Sargent. New York City: Harry N. Abrams. p. 11. ISBN 0-8109-3833-2.

- Olson, p. 9.

- Olson, p. 10.

- Olson, p. 15.

- Olson, p. 18.

- Carl Little, The Watercolors of John Singer Sargent, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998, p. 7, ISBN 0-520-21969-4

- Olson, p. 23

- Olson, p. 27.

- Olson, p. 29.

- Fairbrother, p. 13.

- Little, p. 7.

- Olson, p. 46.

- Elizabeth Prettejohn: Interpreting Sargent, p. 9. Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1998.

- Olson, p. 55.

- Fairbrother, p. 16.

- Prettejohn, p. 14, 1998.

- Prettejohn, p. 13, 1998.

- Olson, p. 70.

- Olson, p. 73.

- Fairbrother, p. 33.

- Olson, p. 80.

- "Emil Fuchs papers 1880–1931" (PDF). Brooklyn Museum.

- Ormond, Richard: "Sargent's Art", John Singer Sargent, pp. 25–7. Tate Gallery, 1998.

- Ormond, p. 27, 1998.

- Fairbrother, p. 40.

- Ormond, Richard; Kilmurray, Elaine, Sargent: The Early Portraits, Complete Paintings, Volume 1, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998, p. 114, ISBN 0-300-07245-7

- Fairbrother, p. 45.

- Olson, p. 102.

- Ormand and Kilmurray, p. 113.

- Fairbrother, p. 47.

- Fairbrother, p. 55.

- Cited in Ormond, pp. 27–8, 1998.

- Ormond, p. 28, 1998.

- Fairbrother, p. 43.

- Olson, p. 107.

- Fairbrother, p. 61.

- Olson, plate XVIII

- Ormand and Kilmurray, p. 151.

- Fairbrother, p. 68.

- Fairbrother, pp. 70–2.

- Olson, p. 223.

- Ormand and Kilmurray, p. xxiii.

- Fairbrother, p. 76, price updated by CPI calculator to 2008 at data.bls.gov

- Fairbrother, p. 79.

- Ormond, pp. 28–35, 1998.

- John Singer Sargent at the World's Columbian Exposition, World's Fair Chicago 1893

- "Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife". JSS Virtual Gallery. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- Ormond, pp. 169–171, 1998.

- Ormond, p. 148, 1998.

- Exhibit at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas

- "John Singer Sargent 1856–1925. Mr and Mrs IN Phelps Stokes 1897, Oil on canvas". Studios and portraits – Queensland Art Gallery – Gallery of Modern Art. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- "Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, 1897, by John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Oil on canvas". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- Fairbrother, p. 97.

- Little, p. 12.

- Fairbrother, p. 101.

- Fairbrother, p. 118.

- Olson, p. 227.

- Fairbrother, p. 124.

- McCouat, Philip. "ROSE-MARIE ORMOND SARGENT'S MUSE AND "THE MOST CHARMING GIRL THAT EVER LIVED"". Journal of Art in Society. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Eustace, Katharine (1999). Twentieth C. Paintings in Asholeum Museum. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-1-85444-117-1.

- "Sketch of a Balustrade, San Domenico e Sisto, Rome".

- "Charles W. Eliot". Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- "In the history of portraiture there is no other instance of a major figure abandoning his profession and shutting up shop in such a peremptory way." Ormond, Page 38, 1998.

- Kilmurray, Elaine, "Chronology of Travels", in Sargent Abroad: Figures and Landscapes, p. 242. New York: Abbeville Press, 1997.

- Madsen, Annelise K.; Ormond, Richard; Broadway, Mary (2018). John Singer Sargent & Chicago's Gilded Age. Chicago, Illinois: The Art Institute of Chicago. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-300-23297-4. LCCN 2017056054. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Fairbrother, p. 131.

- Fairbrother, p. 133.

- "EmbARK Web Kiosk". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Little, p. 11.

- Prettejohn, pp. 66–69, 1998.

- Fairbrother, p. 148.

- Ormond, p. 276, 1998.

- Little, p. 110.

- Little, p. 17.

- "John Singer Sargent's President Theodore Roosevelt". www.jssgallery.org.

- "Exhibitions – 1916, Royal Society of Portrait Painters, hosted at the Grafton Galleries". www.jssgallery.org.

- The Sargent Murals at the Boston Public Library Archived June 2, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- John Singer Sargent's "Triumph of Religion" at the Boston Public Library: Creation and Restoration, Ed. Narayan Khandekar, Gianfranco Pocobene, and Kate Smith, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museum, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

- "New Painting at Public Library Stirs Jews to Vigorous Protest". Donald Hendersonsyn The Boston Globe, November 9, 1919, p. 48.

- "BPL - Art -- Sargent Murals". Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- "Jenna Weissman Joselit: Restoring the 'American Sistine Chapel'... How Sargent's 'Synagogue' Provoked a Nation – Forward.com". The Jewish Daily Forward. August 4, 2010.

- Little, p. 135.

- "At Home with Wilde, Sargent, and Whistler", Londonist, 2014

- Everett, Lucinda, "Too 'dangerous' for Henry James: Violet Paget, the radical lesbian writer who shook the art world", The Telegraph, March 2018

- Olson, Stanley, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait, St Martin's Griffin, 2001, New York, ISBN 0-312-27528-5, p. 199

- Failing, Patricia, "The Hidden Sargent", Art News, May 2001

- Davis, Deborah, Strapless: John Singer Sargent And The Fall Of Madam X, Tarcher, 2003, ASIN: B015QKNWS0, p. 254

- Moss, Dorothy, "John Singer Sargent, 'Madame X' and 'Baby Millbank'", The Burlington Magazine, May 2001, No. 1178, Vol. 143

- Little, p. 141.

- Tóibín, Colm, The secret life of John Singer Sargent,The Telegraph, February 15, 2015

- Ormond, Richard; Kilmurray, Elaine, John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits, Complete Paintings, Volume 1. Yale University Press, 1998, p. 88

- Diliberto, Gioia. "Sargent's Muses: Was Madam X Actually a Mister?", The New York Times, May 18, 2003

- Fairbrother, Trevor, John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist, Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08744-6, p. 220, n.7

- Fairbrother, Trevor, John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist, Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-300-08744-6, p. 139, n.4.

- Davis, Deborah, Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madam X, Tarcher, 2003, ASIN: B015QKNWS0, 143–145

- Olson, Stanley, John Singer Sargent, His Portrait, New York: St Martin's Press, 1986, p. 88. ISBN 0-312-44456-7

- Kilmurray, Elaine, "Traveling Companions", in Sargent Abroad: Figures and Landscapes, pp. 57–8. New York: Abbeville Press, 1997.

- Kilmurray, "Chronology of Travels", p. 240, 1997.

- "The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- This from Auguste Rodin, upon seeing The Misses Hunter in 1902. Ormond and Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits, p. 150. Yale University, 1998.

- Rewald, John: Camille Pissarro: Letters to his Son Lucien, p. 183. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

- Prettejohn, p. 73, 1998.

- Sargent's friend Vernon Lee referred to the artist's "outspoken love of the exotic...the unavowed love of rare kinds of beauty, for incredible types of elegance." Charteris, Evan: John Sargent: With Reproductions from His Paintings and Drawings, p. 252. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1927.

- Fairbrother, p. 140.

- Fairbrother, p. 141.

- "John Singer Sargent". Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- See Trevor Fairbrother," Warhol Meets Sargent at Whitney," Arts Magazine 6 (February 1987): 64–71.

- Fairbrother, p. 145.

- "Painters and Sculptors' Gallery Association to Begin Work", The New York Times, December 19, 1922.

- Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections, Columbus Museum of Art, p. 34, ISBN 0-8109-1811-0.

- "John Singer Sargent". Necropolis Notables. The Brookwood Cemetery Society. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- "Tate – Website undergoing maintenance".

- "Taken from Sargent's Sketchbook", The New York Times, February 12, 1928; "Sargent Sketches in New Exhibit Here", The New York Times, February 14, 1928.

- "Sotheby's: Fine Art Auctions & Private Sales for Contemporary, Modern & Impressionist, Old Master Paintings, Jewellery, Watches, Wine, Decorative Arts, Asian Art & more – Sotheby's". Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- The Age, December 3, 2004.

General sources

- Davis, Deborah. Sargent's Women. Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003, pp. 11–23. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8

- Fairbrother, Trevor: John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist. Seattle Art Museum, Yale University Press, 2001, p. 139, n.4. ISBN 0-300-08744-6

- Joselit, Jenna Weissman. "Restoring the American 'Sistine Chapel'". The Forward, August 13, 2010.

- Khandekar, Narayan; Pocobene, Gianfranco; Smith, Kate (eds.). John Singer Sargent's Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library: Creation and Restoration. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museum; New Haven, Conn.: Distributed by Yale University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780300122909

- Kilmurray, Elaine: Sargent Abroad. Abbeville Press, 1997, pp. 57–8, 242.

- Lehmann-Barclay, Lucie. "Public Art, Private Prejudice." Christian Science Monitor, January 7, 2005, p. 11.

- "New Painting at Boston Public Library Stirs Jews to Vigorous Protest." Boston Globe, November 9, 1919, p. 48.

- Noël, Benoît et Jean Hournon: Portrait de Madame X in Parisiana – la Capitale des arts au XIXème siècle, Les Presses Franciliennes, Paris, 2006. pp. 100–105.

- Ormond, Richard: "Sargent's Art" in John Singer Sargent, pp. 25–7. Tate Gallery, 1998.

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth: Interpreting Sargent. Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1998, p. 9.

- Rewald, John: Camille Pissarro: Letters to his Son Lucien, p. 183. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980.

Further reading

- Adelson, Warren; Gerdts, William H.; Kilmurray, Elaine; Zorzi, Rosella Mamoli; Ormond, Richard; Oustinoff, Elizabeth (2006). Sargent's Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11717-2.

- Avery, Kevin J. (2002). American Drawings and Watercolors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born Before 1835. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 1588390608.

- Capó, Jr, Julio (2017). Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-3520-0.

- Cash, Sarah; Heller, Nancy G.; Kilmurray, Elaine; Ormond, Richard; Barón, Javier; Sharpe, Chloe; Southwick, Catherine (2022). Sargent and Spain. Washington: National Gallery of Art with Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300266467.

- Corsano, Karen; Williman, Daniel (2014). John Singer Sargent and His Muse: Painting Love and Loss. Maryland: Rowman & Litchfield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3050-7.

- Cox, Devon (2015). The Street of Wonderful Possibilities: Whistler, Wilde & Sargent in Tite Street. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 9780711236738.

- Gallati, Barbara Dayer (2015). "John Singer Sargent's International Network of Artists and Muses," in John Singer Sargent: Painting Friends. London: National Portrait Gallery. ISBN 978 1 85514 550 4.

- Herdrich, Stephanie L; Weinberg, H. Barbara (2000). American Drawings and Watercolors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: John Singer Sargent. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-87099-952-4.

- Mount, Charles Merrill (1955). John Singer Sargent. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Rubin, Stephen D. (1991). John Singer Sargent's Alpine Sketchbooks: A Young Artist's Perspective. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-19378-7.

- Thomas, John (2017). Redemption Achieved: John Singer Sargent's Crucifixion of Christ with Adam and Eve and Its Place in His Work. Wolverhampton: Twin Books. ISBN 978-0-9934781-1-6.

External links

- 113 artworks by or after John Singer Sargent at the Art UK site

- Biography, Style and Artworks

- John Singer Sargent – Gallery of 809 paintings.

- "Mrs. Edward Goetz" at [Brigham Young Museum of Art]

- John Singer Sargent Virtual Gallery

- Sargent at Harvard – archived searchable database by Harvard University Art Museums

- The Sargent Murals at Boston Public Library

- John Singer Sargent – News, biography and works

- John Singer Sargent, Miss M. Carey Thomas, July 1899, oil on canvas, Bryn Mawr College Art and Artifact Collections

- John Singer Sargent Letters Online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- "Sargent and the Sea at the Royal Academy", review by Richard Dorment, The Guardian, July 12, 2010

- John Singer Sargent at Harper's Magazine

- John Singer Sargent at Smithsonian American Art Museum

- John Singer Sargent exhibition catalogs

- A video discussion about Sargent's Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose from Smarthistory at Khan Academy.

- John Singer Sargent's interest in picture frames

- Works by John Singer Sargent at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Singer Sargent at Internet Archive

- John Singer Sargent at the Jewish Museum

- Joseph J. Rishel, In the Luxembourg Gardens in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art digital scholarly catalogue (fully available as a free PDF)

- John Singer Sargent: Secrets of Composition and Design

- Sargent and Spain, National Gallery of Art, October 2, 2022 – January 2, 2023