Khmer people

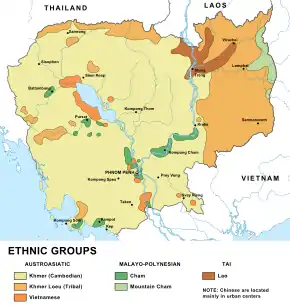

Khmer people (Khmer: ជនជាតិខ្មែរ, Chônchéatĕ Khmêr [cɔnciət kʰmae]), also known as Cambodian people (Khmer: ប្រជាជនកម្ពុជា។, Brachachn Kampouchea), are a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Cambodia. They comprise over 90% of Cambodia's population of 17 million.[12] They speak the Khmer language, which is part of the larger Austroasiatic-language family found in parts of Southeast Asia (including Vietnam, Laos and Malaysia), parts of central, eastern, and northeastern India, parts of Bangladesh in South Asia, in parts of Southern China and numerous islands in the Indian Ocean.

ជនជាតិខ្មែរ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Khmer dress | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 18–19 million[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17,300,000[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,320,000[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,146,685[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 331,733[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 500,000[5] (2022) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Theravada Buddhism; Hinduism and animisim (historically) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other Austroasiatic peoples (especially Khmer Krom, Khmer Loeu, Northern Khmer, Sino-Khmer) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The majority of the Khmers follow Theravada Buddhism. Significant populations of Khmers reside in adjacent areas of Thailand (Northern Khmer) and the Mekong Delta region of neighboring Vietnam (Khmer Krom), while there are over one million Khmers in the Khmer diaspora living mainly in France, the United States, and Australia.

Distribution

Cambodia

The majority of the world's Khmers live in Cambodia, the population of which is over 90% Khmers.[13][14]

Thailand and Vietnam

There are also significant Khmer populations native to Thailand and Vietnam. In Thailand, there are over one million Khmers (known as the Khmer Surin), mainly in Surin (Sorin), Buriram (Borei Rom) and Sisaket (Srei Saket) provinces. Estimates for the number of the Khmers in Vietnam (known as the Khmer Krom) vary from the 1.3 million given by government data to 7 million advocated by the Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation.[15]

| Province | 1990 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|

| Buriram[16] | 0.3% | 27.6% |

| Chanthaburi[17] | 0.6% | 1.6% |

| Maha Sarakham[18] | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Roi Et[19] | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Sa Kaew[20] | — | 1.9% |

| Sisaket[21] | 30.2% | 26.2% |

| Surin[22] | 63.4% | 47.2% |

| Trat[23] | 0.4% | 2.1% |

| Ubon Ratchathani[24] | 0.8% | 0.3% |

Western nations

Due to migration as a result of the Cambodian Civil War and Cambodian Genocide, there is a large Khmer diaspora residing in the United States, Canada, Australia and France.

History

Origin myths

According to one Khmer legend attributed by George Coedes to a tenth century inscription, the Khmers arose from the union of the brahmin Kambu Swayambhuva and the apsara ("celestial nymph") Mera. Their marriage is said to have given rise to the name Khmer and founded the Varman dynasty of ancient Cambodia.[25]

A more popular legend, reenacted to this day in the traditional Khmer wedding ceremony and taught in elementary school, holds that Cambodia was created when an Indian Brahmin priest named Kaundinya I (commonly referred to as Preah Thong) married Princess Soma, a Nāga (Neang Neak) princess. Kaundinya sailed to Southeast Asia following an arrow he saw in a dream. Upon arrival he found an island called Kok Thlok and, after conquering Soma's Naga army, he fell in love with her. As a dowry, the father of princess Soma drank the waters around the island, which was revealed to be the top of a mountain, and the land below that was uncovered became Cambodia. Kaundinya and Soma and their descendants became known as the Khmers and are said to have been the rulers of Funan, Chenla and the Khmer Empire.[26] This myth further explains why the oldest Khmer wats, or temples, were always built on mountaintops, and why today mountains themselves are still revered as holy places.

Arrival in Southeast Asia

The Khmers, an Austroasiatic people, are one of the oldest ethnic groups in the area, having filtered into Southeast Asia from southern China,[27] possibly Yunnan, or from Northeast India around the same time as the Mon, who settled further west on the Indochinese Peninsula and to whom the Khmer are ancestrally related.[28] Most archaeologists and linguists, and other specialists like Sinologists and crop experts, believe that they arrived no later than 2000 BCE (over four thousand years ago) bringing with them the practice of agriculture and in particular the cultivation of rice. This region is also one of the first places in the world to use bronze. They were the builders of the later Khmer Empire, which dominated Southeast Asia for six centuries beginning in 802, and now form the mainstream of political, cultural, and economic Cambodia.[29]

The Khmers developed the Khmer alphabet, which in turn gave birth to the later Thai and Lao alphabets. The Khmers are considered by archaeologists and ethnologists to be indigenous to the contiguous regions of Isan, southern Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam. That is to say the Cambodians have historically been a lowland people who lived close to one of the tributaries of the Mekong River. The reason they migrated into Southeast Asia is not well understood, but scholars believe that Austroasiatic speakers were pushed south by invading Tibeto-Burman speakers from the north as evident by Austroasiatic vocabulary in Chinese, because of agricultural purposes as evident by their migration routes along major rivers, or a combination of these and other factors.

The Khmer are considered a part of Greater India, owing to them adopting Indian culture, traditions and religious identities. The first powerful trading kingdom in Southeast Asia, the Kingdom of Funan, was established in southeastern Cambodia and the Mekong Delta in the first century, although extensive archaeological work in Angkor Borei District near the modern Vietnamese border has unearthed brickworks, canals, cemeteries and graves dating to the fifth century BCE.

During the Funan period (1st century - sixth century CE) the Khmer also acquired Buddhism, the concept of the Shaiva imperial cult of the devaraja and the great temple as a symbolic world mountain. The rival Khmer Chenla Kingdom emerged in the fifth century and later conquered the Kingdom of Funan. Chenla was an upland state whose economy was reliant on agriculture whereas Funan was a lowland state with an economy dependent on maritime trade.

These two states, even after conquest by Chenla in the sixth century, were constantly at war with each other and smaller principalities. During the Chenla period (5th-8th century), Khmers left the world's earliest known zero in one of their temple inscriptions. Only when King Jayavarman II declared an independent and united Cambodia in 802 was there relative peace between the two lands, upper and lowland Cambodia.

Jayavarman II (802–830), revived Khmer power and built the foundation for the Khmer Empire, founding three capitals—Indrapura, Hariharalaya, and Mahendraparvata—the archeological remains of which reveal much about his times. After winning a long civil war, Suryavarman I (reigned 1002–1050) turned his forces eastward and subjugated the Mon kingdom of Dvaravati. Consequently, he ruled over the greater part of present-day Thailand and Laos, as well as the northern half of the Malay Peninsula. This period, during which Angkor Wat was constructed, is considered the apex of Khmer civilization.

Khmer Empire (802–1431)

The Khmer kingdom became the Khmer Empire and the great temples of Angkor, considered an archeological treasure replete with detailed stone bas-reliefs showing many aspects of the culture, including some musical instruments, remain as monuments to the culture of the Cambodia. After the death of Suryavarman II (1113–50), Cambodia lapsed into chaos until Jayavarman VII (1181–1218) ordered the construction of a new city. He was a Buddhist, and for a time, Buddhism became the dominant religion in Cambodia. As a state religion, however, it was adapted to suit the Deva Raja cult, with a Buddha Raja being substituted for the former Shiva Raja or Vishnu Raja.

The rise of the Tai kingdoms of Sukhothai (1238) and Ayutthaya (1350) resulted in almost ceaseless wars with the Khmers and led to the destruction of Angkor in 1431. They are said to have carried off 90,000 prisoners, many of whom were likely dancers and musicians.[30] The period following 1432, with the Khmer people bereft of their treasures, documents, and human culture bearers, was one of precipitous decline.

Post-empire (1431–present)

In 1434, King Ponhea Yat made Phnom Penh his capital, and Angkor was abandoned to the jungle. Due to continued Siamese and Vietnamese aggression, Cambodia appealed to France for protection in 1863 and became a French protectorate in 1864. During the 1880s, along with southern Vietnam and Laos, Cambodia was drawn into the French-controlled Indochinese Union. For nearly a century, the French exploited Cambodia commercially, and demanded power over politics, economics, and social life.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the political situation in Cambodia became chaotic. King Norodom Sihanouk (later, Prince, then again King), proclaimed Cambodia's independence in 1949 (granted in full in 1953) and ruled the country until March 18, 1970, when he was overthrown by General Lon Nol, who established the Khmer Republic. On April 17, 1975, Khmer Rouge, who under the leadership of Pol Pot combined Khmer nationalism and extreme Communism, came to power and virtually destroyed the Cambodian people, their health, morality, education, physical environment, and culture in the Cambodian genocide.

On January 7, 1979, Vietnamese forces ousted the Khmer Rouge. After more than ten years of painfully slow rebuilding, with only meager outside help, the United Nations intervened resulting in the Paris Peace Accord on October 23, 1992, and created conditions for general elections in May 1993, leading to the formation of the current government and the restoration of Prince Sihanouk to power as King in 1993. The Khmer Rouge continued to control portions of western and northern Cambodia until the late 1990s, when they surrendered to government forces in exchange for either amnesty or re-adjustment for positions into the Cambodian government.

In the 21st century, Cambodia's economy has grown faster than that of any other country in Asia except for China and India. Today, post-conflict Cambodia exports over $5 billion worth of clothing, mainly to the United States and the European Union, is one of the top ten exporters of rice in the world, and has seen international tourist arrivals balloon from less than 150,000 in 2000 to over 4.2 million in 2013.

Cambodia is no longer seen as being on the brink of disaster, a reputation it gained in the 1980s and 1990s as guerilla-style warfare was still being waged by the Khmer Rouge until their ceasefire in 1998. Cambodians in the diaspora are returning to their homeland to start businesses, and immigrant Western workers in fields as diverse as architecture, archaeology, philanthropy, banking, hospitality, agriculture, music, diplomacy and garments are increasingly attracted to Cambodia because of its relaxed lifestyle and traditional way of life.

Culture and society

The culture of the ethnic Khmers is fairly homogeneous throughout their geographic range. Regional dialects exist, but are mutually intelligible. The standard is based on the dialect spoken throughout the Central Plain,[31] a region encompassed by the northwest and central provinces. The varieties of Khmer spoken in this region are representative of the speech of the majority of the population. A unique and immediately recognizable dialect has developed in Phnom Penh that, due to the city's status as the national capital, has been modestly affected by recent French and Vietnamese influence.

Other dialects are Northern Khmer dialect, called Khmer Surin by Khmers, spoken by over a million Khmer native to Northeast Thailand; and Khmer Krom spoken by the millions of Khmer native to the Mekong Delta regions of Vietnam adjacent to Cambodia and their descendants abroad. A little-studied dialect known as Western Khmer, or Cardamom Khmer, is spoken by a small, isolated population in the Cardamom Mountain range extending from Cambodia into eastern Central Thailand. Although little studied, it is unique in that it maintains a definite system of vocal register that has all but disappeared in other dialects of modern Khmer.

The modern Khmer strongly identify their ethnic identity with their religious beliefs and practices, which combine the tenets of Theravada Buddhism with elements of indigenous ancestor-spirit worship, animism and shamanism.[32] Most Cambodians, whether or not they profess to be Buddhists or other faiths, believe in a rich supernatural world. Several types of supernatural entities are believed to exist; they make themselves known by means of inexplicable sounds or happenings. Among these phenomena are kmaoch ខ្មោច (ghosts), pret ប្រែត (comes in many forms depending on their punishments) and beisach បិសាច (monsters) [these are usually the spirits of people who have died a violently, untimely, or unnatural deaths]; arak អារក្ស (evil spirits, devils), ahp krasue, neak ta អ្នកតា (tutelary spirit or entity residing in inanimate objects; land, water, trees etc.), chomneang/mneang phteah ជំនាងផ្ទះ/ម្នាងផ្ទះ(house guardians), meba មេបា (ancestral spirits), and mrenh kongveal ម្រេញគង្វាល (little mischief spirit guardians dressed in red).[33] All spirits must be shown proper respect, and, with the exception of the mneang phteah and mrenh kongveal, they can cause trouble ranging from mischief to serious life-threatening illnesses.

The majority of the Cambodians live in rural villages either as rice farmers or fishermen. Their life revolves around the Wat (temple) and the various Buddhist ceremonies throughout the year. However, if Cambodians become ill, they will frequently see a kru khmae (shaman/healer), whom they believe can diagnose which of the many spirits has caused the illness and recommend a course of action to propitiate the offended spirit, thereby curing the illness.[34] The kru khmae is also learned in herb lore and is often sought to prepare various "medicines" and potions or for a magical tattoo, all believed to endow one with special prowess and ward off evil spirits or general bad luck.[34] Khmer beliefs also rely heavily on astrology, a remnant of Hinduism. A fortune teller, called hao-ra (astrologists) or kru teay in Khmer, is often consulted before major events, like choosing a spouse, beginning an important journey or business venture, setting the date for a wedding and determining the proper location for building new structures.

Throughout the year, the Cambodian celebrate many holidays, most of a religious or spiritual nature, some of which are also observed as public holidays. The two most important are Chol Chhnam (Cambodian New Year) and Pchum Ben ("Ancestor Day"). The Cambodian Buddhist calendar is divided into 12 months with the traditional new year beginning on the first day of khae chaet, which coincides with the first new moon of April in the western calendar. The modern celebration has been standardized to coincide with April 13.

Cambodian culture has influenced Thai and Lao cultures and vice versa. Many Khmer loanwords are found in Thai and Lao, while many Lao and Thai loanwords are found in Khmer. The Thai and Lao alphabets are also derived from the Khmer script.

Genetics

The Khmer people are genetically closely related to other Southeast Asian populations. They show strong genetic relation to other Austroasiatic people in Southeast Asia and East Asia and have a minor genetic influence from Indian people.[35] Cambodians trace ~16% of their ancestry to a Eurasian population that is equally related to both Europeans and East Asians, while the remaining 84% of their ancestry is related to other Southeast Asians, particularly to a source similar to the Dai people.[36] Another study suggests that Cambodians trace ~19% of their ancestry to a similar Eurasian population related to modern-day Central Asians, South Asians, and East Asians, while the remaining 81% of their ancestry is related specifically to modern-day Dai and Han people.[37]

The genetic testing website 23andme groups Khmer people under the "Indonesian, Khmer, Thai & Myanmar" reference population. This reference population contains people who have had recent ancestors from Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand.[38]

Immunoglobulin G

Hideo Matsumoto, professor emeritus at Osaka Medical College tested Gm types, genetic markers of immunoglobulin G, of Khmer people for a 2009 study.[39] The study found that the Gm afb1b3 is a southern marker gene possibly originating in southern China and found at high frequencies across southern China, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Assam and parts of the Pacific Islands.[39] The study found that the average frequency of Gm afb1b3 was 76.7% for the Khmer population.[39]

Gallery

Pchum Ben, also known as Ancestors Day

Pchum Ben, also known as Ancestors Day Khmer groom and bride

Khmer groom and bride Khmer New Year celebration

Khmer New Year celebration Khmer elder washing Buddha statues

Khmer elder washing Buddha statues Khmer trot dance

Khmer trot dance Khmer traditional dancers

Khmer traditional dancers Young Khmer children

Young Khmer children.jpg.webp) Group of young Khmer girls

Group of young Khmer girls Group of Khmers at a village meeting

Group of Khmers at a village meeting Apsara dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia

Apsara dancers of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia

See also

- Anvaya (organization)

- Cambodian cuisine

- Chinese Cambodian

- Khmer Krom

- Khmer Loeu

- Ethnic groups in Cambodia

- Ethnic groups in Thailand

- Ethnic groups in Vietnam

References

- Benjamin Walker, Angkor Empire: A History of the Khmer of Cambodia, Signet Press, Calcutta, 1995.

Notes

- Hattaway, Paul, ed. (2004), "Khmer", Peoples of the Buddhist World, William Carey Library, p. 133

- "General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2019" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics. Ministry of Planning. June 2019. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- "Report on Results of the 2019 Census". General Statistics Office of Vietnam. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "ASIAN ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH ONE OR MORE OTHER RACES, AND WITH ONE OR MORE ASIAN CATEGORIES FOR SELECTED GROUPS". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2017. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- Danaparamita, Aria (November 21, 2015). "Solidarité". The Cambodia Daily. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- "Estimated Resident Population by Country of Birth, 30 June 1992 to 2016". stat.data.abs.gov.au. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada". Statistics Canada.

- "2006 and 2013 Census: Cambodians- Facts and Figures". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand .

- "Results of Population and Housing Census 2015" (PDF). Lao Statistics Bureau. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Ausländeranteil in Deutschland bis 2018". De.statista.com. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- "Population by country of birth and year". Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Cambodia. CIA World FactBook.

- "Ethnic groups statistics - countries compared". Nationmaster. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- "Birth Rate". CIA – The World Factbook. Cia.gov. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- Archived May 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Buriram" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- "Chanthaburi" (PDF). Nso.go.th. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Maha Sarakham" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- "Roi Et" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Sakaeo" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- "Si Sa Ket" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- "Surin" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- "Khat" (PDF). Web.nso.go.th. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- "Ubon Ratchathani" (PDF). Web.nso.go.t. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- D'après l'épigraphie cambodgienne du X° siècle, les rois des "Kambuja" prétendaient descendre d'un ancêtre mythique éponyme, le sage ermite Kambu, et de la nymphe céleste Mera, dont le nom a pu être forgé d'après l'appellation ethnique "khmèr" (George Coedes). ; See also: Indianised States of Southeast Asia, 1968, p 66, George Coedes.

- Miriam T. Stark (2006). "9 Textualized Places, Pre-Angkorian Khmers and Historicized Archaeology by Miriam T. Stark - Cambodia's Origins and the Khok Thlok Story" (PDF). University of Hawaii. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- Ross, Russell R. (December 1987). Cambodia: A Country Study (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 6. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- SarDesai, D R (October 3, 2018). Southeast Asia, Student Economy Edition: Past and Present. Taylor & Francis. p. 11. ISBN 9780429961601. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- Zhang, Xiaoming; Liao, Shiyu; Qi, Xuebin; Liu, Jiewei; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Zhang, Hui; Yang, Zhaohui; Serey, Bun; Tuot, Sovannary (October 20, 2015). "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro- Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent OPEN". Scientific Reports. 5: 15486. doi:10.1038/srep15486. PMC 4611482. PMID 26482917.

- Thailand 1969:151, Blanchard 1958:27

- Huffman, Franklin. 1970. Cambodian System of Writing and Beginning Reader. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01314-0

- Faith Traditions in Cambodia Archived August 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine; pg. 8; accessed August 21, 2006

- //http://anarchak.com/article/40347//

- Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Papiha, S. S.; Mastana, S. S.; Singh, N.; Roberts, D. F. (1994). "Khmers of Cambodia: A comparative genetic study of the populations of Southeast Asia". American Journal of Human Biology. 6 (4): 465–479. doi:10.1002/ajhb.1310060408. ISSN 1520-6300. PMID 28548253. S2CID 23979421.

- Pickrell, Joseph; Pritchard, Jonathan (November 2012). "Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data". PLOS Genetics. 8 (11): e1002967. arXiv:1206.2332. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002967. PMC 3499260. PMID 23166502.

- Hellenthal, Garrett; Busby, George; Band, Gavin; Wilson, James; Capelli, Cristian; Falush, Daniel; Myers, Simon (February 14, 2014). "A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History". Science. 343 (6172): 747–751. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..747H. doi:10.1126/science.1243518. PMC 4209567. PMID 24531965.

- 23andMe Reference Populations & Regions. (n.d.). 23andMe. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://customercare.23andme.com/hc/en-us/articles/212169298-23andMe-Reference-Populations-Regions#h_f676b3fd-8072-48fe-8eeb-ea577ea2dfd2

- Matsumoto, Hideo (2009). "The origin of the Japanese race based on genetic markers of immunoglobulin G." Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 85 (2): 69–82. Bibcode:2009PJAB...85...69M. doi:10.2183/pjab.85.69. PMC 3524296. PMID 19212099.

_(2341905162).jpg.webp)

_(2334493467).jpg.webp)